1. Introduction

During the Corona Virus Disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic, more than 35 million people were infected with the Sars-CoV-2 virus and more than 1 million deaths were recorded. Despite the fact that in Romania ischemic heart disease was the main cause of mortality, in 2020 COVID-19 caused approximately 16.000 deaths in Romania (5% of all deaths). However the indicator of excess mortality suggests that the number of direct and indirect deaths caused by COVID-19 in 2020 could be considered much higher. Several preventive measures must be taken to avoid the spread of infection among healthcare professionals and patients with digestive disease, including the use of personal protective equipment, greater attention to endoscopic room hygiene and rescheduling of non- urgent procedures. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on access to care for cancer patients [

1]. This pandemic can affect the economy and cause social and political disruptions. This rise in pandemic can be attributed to global travel and the exploitation of the environment. For these outbreaks to subside and be prevented, there is an urgent need to identify emerging outbreaks and create policies to act accordingly. Well-planned public health structures, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and societal policies are needed to disseminate public health preparedness and guide the emergent response, as well as identify gaps in knowledge and solve them [

2]. The prevention of transmission and the treatment of patients with Sars-CoV-2 infection were the main objectives of doctors, which affected other programs of the health systems such as the diagnosis and treatment of oncological diseases [

3]. COVID-19 is a threat to patients with chronic conditions, including those with malignancies [

4]. Awareness of the need to prioritize the provision of medical care represented one of the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reorganization and diminishing the current activities were imposed, with the preservation of urgent procedures and the postponement of semi-urgent and/or elective procedures. The pandemic shows its consequences not only through the number of deaths or patients with pulmonary sequelae, but also through an important segment of patients who presented symptoms of the upper or lower digestive tract but who, due to the decrease of the elective endoscopic examinations, did not have benefited from timely diagnosis [

5]. The fear of infection with the Sars-CoV-2 virus caused a decrease in the addressability of patients, so that a large number of gastrointestinal cancers remained undiagnosed or untreated. The prognosis of patients with gastrointestinal malignancies is profoundly affected if standard care is delayed. Globally, the health policies imposed by the WHO have generated the impossibility of treating all patients, which has determined an ethical dilemma pertaining to the balance of utilitarianism versus deontology, regarding the patient’s access to public health services.

The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of delayed diagnosis on the staging of digestive cancers within the context of health crisis management, while considering bioethical principles. This is a crucial area of research, especially in the context of health crises where healthcare systems may face challenges and disruptions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

All patients gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Iasi, Romania, Approval for Doctoral Research Series J, number 34/18.01.2021, issued for Andreea Luiza Palamaru.

Medical and personal information are anonymous and the requirement for a special informed approval was therefore waived.

2.2. Patients

The prospective study included patients who postponed elective endoscopic examinations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, 205 patients who underwent elective endoscopic diagnostic procedures within the Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatolgy, St. Spiridon Clinical Emergency Hospital of Iasi, Romania after the lifting of sanitary restrictions, between April 1st, 2021 and - April 1st, 2022, have been included in the study.

2.3. Patient Selection

All patients who performed endoscopic explorations were over 18 years old, presented clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of digestive impairment or biological data were objectified that required the performance of endoscopic exploration. They signed the informed consent form, prior to the procedure. We included in the study patients who had histopathological confirmation of digestive tract cancers and who received tumor staging by Computer Tomography with TNM classification. Patients without histopathological confirmation and those in whom endoscopic procedures were performed in an emergency setting have been excluded from the study.

2.4. Data Collection

Each patient included in the study was evaluated for the identification of risk factors through anamnesis, local clinical examination and laboratory tests, according to the protocols in force. For each patient, we gathered: demographic data, treatment timelines, discovery at different cancer stages and detailed tumor staging based on both pathology and radiological assessments. Such data can be valuable for understanding the characteristics of the patient population, treatment outcomes and the relationship between the variables mentioned. Our staging was based on the TNM classification in its latest update in 2016.

The anamnesis aimed to identify the duration of persistence of upper or lower digestive tract symptoms, the medication followed by the patient at home, but also the positive personal history for infection with the Sars-CoV-2 virus. In patients on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy, treatment was discontinued prior to endoscopic exploration to maintain a safety profile in case biopsy was required. Biologically, the hemoglobin value was determined to establish the severity of the anemic syndrome and the Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) was performed. Referring to the statistical estimates, we divided the patients into 2 groups according to the period corresponding to the transition of colon cancer from a TNM stage to an advanced one. 2 groups of patients were obtained: group I was represented by patients whose onset of symptoms was more than 6 months prior to endoscopic exploration and group II of patients with onset of symptoms less than 6 months prior to endoscopic evaluation. This division of patients is motivated by the intention to demonstrate the influence of the time of persistence of symptoms on the stage at which the cancer is diagnosed. The data were collected from medical records. The equipment and materials required for the intervention were: Pentax video gastroscope, model EG-290Kp, Pentax video colonoscope, model EC-380FK2p and biopsy probes.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The information obtained was introduced into a database using the spreadsheet program Microsoft Excel 15.20. The statistical processing of the data was carried out by means of the IBS SPSS Statistics 24 program for Mac OS. We used Kruskal-Wallis Test to determine if there are statistically significant differences between hemoglobin values in the three types of diagnoses. Subsequently, we compared data using Pearson-Chi squared test because we wanted to determine whether our data are significantly different from what we expected.

3. Results

960 patients with upper or lower digestive tract symptoms underwent elective endoscopic procedures during the mentioned period. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 205 patients with histopathologically confirmed upper and lower digestive tract cancers. The patients were aged between 51-70 years and 63,4% of them were male patients. Lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy was performed in 84,4% of patients and 15,6% were evaluated by upper GI endoscopy.

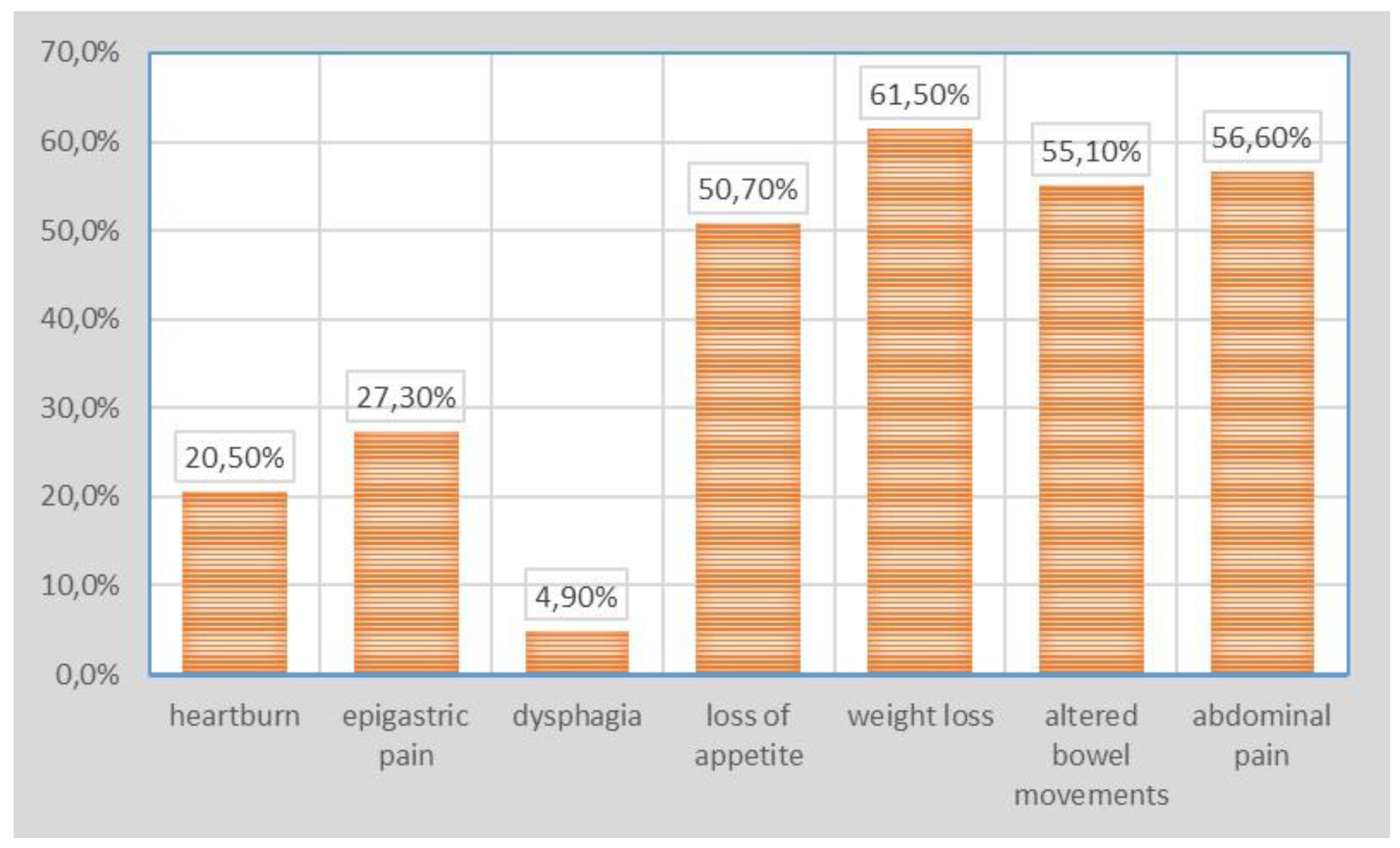

Regarding the clinical parameters, weight loss was most frequently reported (61.5% of cases), followed by abdominal pain (56.6% of cases), altered bowel movements (55.1% of cases) and loss of appetite, observed in 50.7% of cases; other symptoms were observed in lower percentages: epigastric pain (27.3% of cases), heartburn (20.5% of cases) and dysphagia, observed only in isolation (4.9% of cases) (

Figure 1).

Table 1.

General clinical parameters of included patients.

Table 1.

General clinical parameters of included patients.

Endoscopic procedures

Lower GI endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy |

N= 205

173 (84.4%)

32 (15.6%) |

Diagnosis

Colorectal cancer

Esophageal cancer

Gastric cancer |

173 (84.4%)

10 (4.9%)

22 (10.7%) |

T stage

T1

T2

T3a

T3b

T4 |

29 (14.1%)

78 (38%)

23 (11.3%)

50 (24.4%)

25 (12.2%) |

ECOG

0

1

2

3 |

61 (29.8%)

48 (23.4%)

62 (30.2%)

34 (16.6%) |

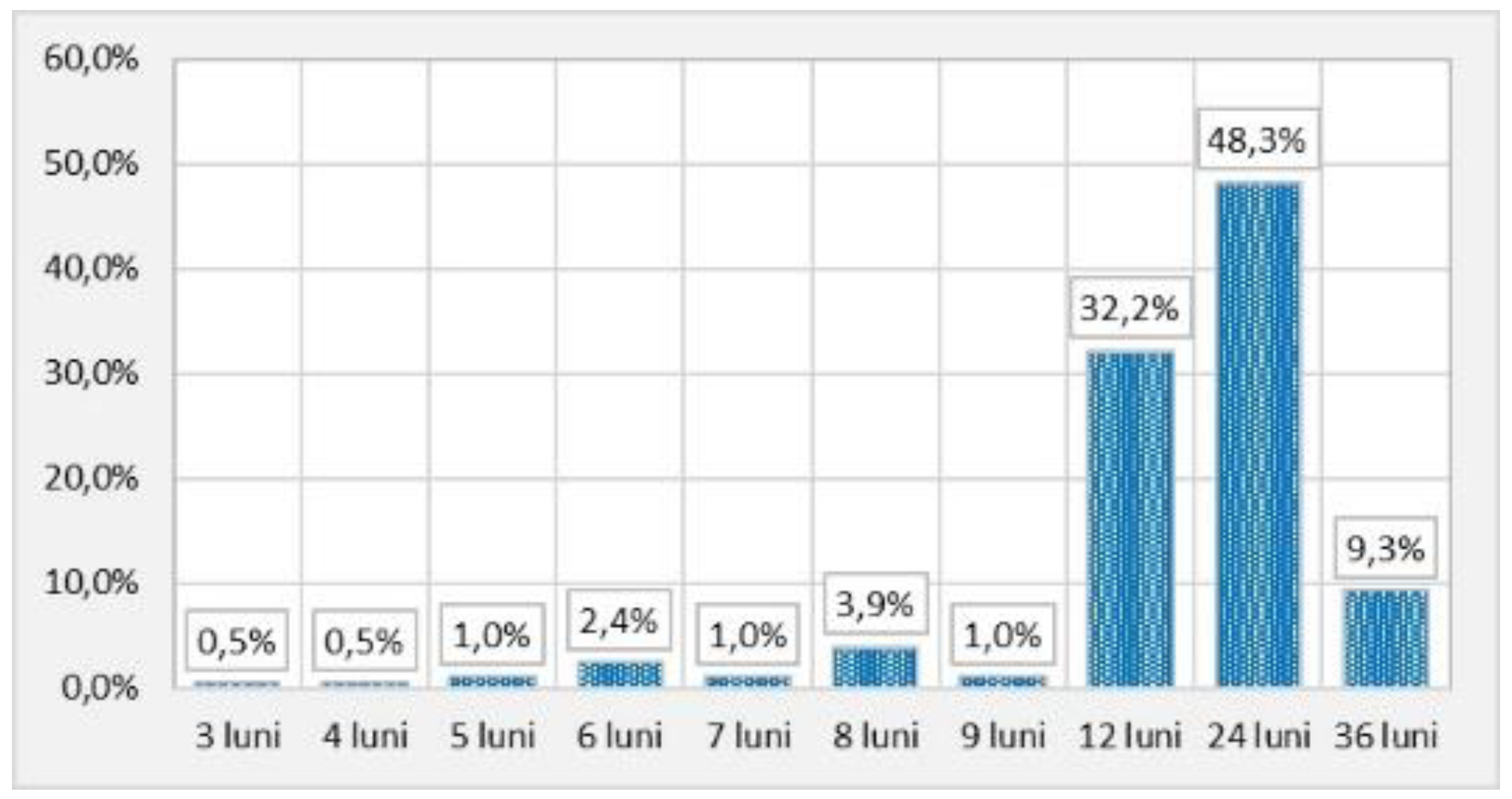

The persistence of symptoms for a duration of 2 years was reported by 48.3% of the patients, while 32.2% presented symptoms for one year (

Figure 2).

The diagnosis of colorectal cancer was confirmed in 84,4% of the patients, gastric cancer in 10,7% and esophageal cancer in 4,9% .

We investigated the presence of iron deficiency anemia by determining the hemoglobin values of patients. The mean value observed is 9.144 ± 1.8376, with a range of variation between 5.3 and 13.9 and a median value of 9.000; the average value of hemoglobin is higher in patients diagnosed with gastric cancer (10.382 ± 2.0720), being the lowest in patients with colorectal cancer (8.981 ± 1.7806). Patients with esophageal cancer have an intermediate hemoglobin value of 9.240 ± 1.2903, the observed differences between hemoglobin values in the three types of diagnoses are statistically significant (p = 0.011) (

Table 2).

We searched whether there are statistically significant associations between the positive FOBT and the diagnosis of digestive cancer; as previously stated, 3 different cancer diagnoses were recorded and the following results: of colorectal cancer cases 60.1% had positive FOBT tests compared to only 40.0% of esophageal cancer cases and respectively 40.9 % of those with gastric cancer. These differences, although present, do not exceed the threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.123) (

Table 3).

We analyzed the presence of alarm and unspecific clinical symptoms on the three types of diagnoses followed and observed statistically significant differences for most of the investigated clinical symptoms. Heartburn is most frequently associated with esophageal cancer (present in 50.0% of cases), epigastric pain are most frequently associated with gastric cancer (63.6% of cases), being also identified in half of patients with esophageal cancer. Dysphagia is identified in half of patients with esophageal cancer. Altered bowel movements are most frequently associated with colorectal cancer (present in 61.3% of cases). Abdominal pain is most frequently associated with colorectal cancer, being reported in 61.8% of cases. In the case of all these clinical symptoms the differences are statistically significant (

Table 4).

Correspondence between the evolutive stage of gastrointestinal cancer and the delay in diagnosis: the T1 stage was identified in 14.1% of the patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer, 2 being classified with the T1a stage, 38% presented the T2 stage - 7 being classified with the T2a, stage T3 was objectified in 35.7% of cases, and 12.2% presented stage T4.

Stage N0 was identified at 2% of patients, while stages N1 and N2 were found in almost equal percentages 48.3% and 49.8%, respectively. The proportion of patients without metastases was 23.4% while almost a quarter of patients were classified as M1 stage. Among patients with persistent symptoms for more than 6 months, only 12.3% were classified in stage T1, stage T2 representing 39.2% and T3 36.0%. The percentage of patients in the T4 stage (12.2%) is slightly higher than the similar patients with symptoms under 6 months (

Table 5).

Regarding the performance status reported by the ECOG investigation, the distribution of patients is relatively even; almost one third of patients (29.8%) have status 0, 23.4% are reported with status 1, almost one third (30.2%) are reported with status 2, the fewest cases (16.6%) being reported with performance status 3.

ECOG performance status is also statistically significantly associated with the presence of a positive FOBT (p = 0.001); thus the positive FOBT was mainly observed in patients with ECOG performance status 3 (82.4% of them); in the other categories of patients the percentages with positive FOBT are lower: 51.6% of those with ECOG 2 status, 64.6% of those with ECOG 1 status and only 42.6% of those with ECOG 0 status (

Table 6).

Statistically significant gender differences are observed in terms of ECOG performance status (p = 0.001). Thus, among patients with status 0, the vast majority are men (80.3%), the proportion of men decreasing significantly between patients with status 1 (68.8%) and those with status 2 or 3 (50.0%), respectively (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic had an undeniable effect on the health system in Romania and worldwide with an estimated 2,3 milion cancer surgery procedures canceled during the height of the pandemic [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Serious concerns related to medical errors secondary to anxiety and burnout [

6]. Thus in both Europe and the United States of America, a large number of gastrointestinal cancers reportedly remained undiagnosed or untreated because patients with alarm or unspecific symptoms either postponed endoscopic investigations for fear of infection with the Sars-CoV-2 virus or did not have access to these examinations due to health policies imposed by the WHO, within the whole Europe [

10,

11,

12].

Similary to other European countries we found that Romanian patients needed to postpone endoscopic procedures despite so called red flag signs that would have required diagnostic procedures. Kapoor et al. evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of alarm symptoms in a clinical prediction model for cancer and prospectively used this model in a cohort study. Their study showed that dysphagia and weight loss significantly were predictive factors for digestive cancer. Furthermore, the most common alarm symptom reported by patients in our study was weight loss, followed by abdominal pain [

13]. In a recent cohort study, Rasmussen et al. evaluated the prevalence of symptom experience in the general population related to specific and non-specific symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer. Persistent abdominal pain was reported as the most common specific alarm symptom [

14].

Among the 960 patients that underwent elective endoscopic procedures in our hospital 21.35% have been diagnosed with digestive tract cancers. Colorectal cancer was most frequently diagnosed. Hamarneh et al showed in a recent study assessing risk factors for colorectal cancer following a positive fecal immunochemical test, that iron deficiency anemia was one of the predictive factors of colorectal cancer and small intestinal cancer [

15]. In a population-based cohort study, Ioannou et al. reported that the patients with iron deficiency anemia has been shown in all patients enrolled in the study, regardless of the type of digestive cancer [

16].

Early diagnosis and treatment have a major impact on the prognosis of any cancer [

17,

18] and any delay may lead to a progression of the disease and can directly influence the patient outcome. Subsequently this cause a burden for the national health system. The main reason for such burden is not only an increased mortality but also the advancement of the cancer stage impacting treatment costs and outcome as some cancers may have become metastatic or inoperable during this delay. Such phenomenon has been evaluated by several concomitant studies and has been therefore designated as stage migration defined as stage shift due to disease progression since first symptoms up until reaching positive diagnosis [

19].

Given the fact that screening programs are performed with the aim of identifying resectable precancerous lesions and treatable early cancers [

16] it is expected that delays in diagnosis due to COVID-19 epidemic caused a significant burden driven by increase in the number of preventable cancer deaths. Recently an increase of over 1,5% in overall mortality related to colorectal cancer has been estimated in the UK, Canada, Australia and in the Netherlands [

20]. Our data showed us that during the 6 months of the pandemic (March 1, 2020 – September 1, 2020), only 202 endoscopic examinations have been performed compared to 797 performed during the corresponding period of 2019. Another study driven in our center showed a dramatic decrease in diagnostic procedures while the number of therapeutic – especially biliopancreatic procedures remained almost the same [

21].

A study conducted by Tinmouth et al. in Canada that compared the number of colonoscopies performed from March to June 2020 with the same time period in 2019, objectified that their number decreased by 60% in 2020 compared to 2019, from 107,034 explorations in 2019 to 36,029 in 2020 [

22]. Given the endoscopy suite restrictions, within all European Union patients with mild clinical symptoms chose a community hospital or nearby health center or even received treatment home (without further examination) as most tertiary hospitals gave priority to critically ill patients. Manes et al showed in a study carried out on the population of northern Italy a 44% decrease in the number of new diagnoses of gastrointestinal cancer, established by endoscopy with biopsy, during the pandemic restrictions [

23].

Regarding the delay in diagnosis recent systematic review presents the Andersen Model of Total Patient Delay and its application in cancer diagnosis. This model highlights the importance of motivation for delaying patient assessment, following three steps: behavioral delay can be explained by the fear of infection with Sars-CoV-2 virus in the hospital, the scheduling delay can be demonstrated by the restrictive measures adopted by the WHO in order to prevent the COVID-19 disease. The last step, treatment delay, can be associeted with the difficulty of getting a hospital appointment [

24].

Progression of cancer up until the time of diagnosis meant that the window of opportunity corresponding to a curative surgical treatment was exceeded. Sud et al emphasized the negative impact of the delay in the diagnosis of digestive cancer. In a study carried out in Great Britain in 2020 it is highlighted that a 3 to 6 month delay in cancer surgery, especially for stage 2 and 3 cancers, can have a substantial impact on survival [

25].

The results are similar to those of our study in which we analyzed the correspondence between the evolutive stage of gastrointestinal cancer and the delay in diagnosis. Thus, the patients with persistent digestive symptoms were diagnosed in advanced stages of gastrointestinal cancer, 39.2% in the T2 stage and 36% in the T3 stage, while only 12.3% of the patients were caught in the T1 stage. Moreover, even after the resumption of standard activity in the endoscopy laboratory, the addressability of patients for endoscopic examinations did not exceed that of the pre-COVID-19 years, leading to an added case load burden [

26].

We have also addressed several ethical management dilemmas as the balance between the need for prioritization and the impossibility of treating all patients equally. In terms of ethical management, we refer to the two principles that are the basis of medical activity: deontology and utilitarianism. Reporting to utilitarianism could provide the answer to two important dilemmas in the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was discussed which patients should benefit from access to endoscopic explorations when the demand exceeds the ability to perform procedures (medical personnel in isolation, limited protective equipment, the risk of infection with the Sars-Cov-2 virus) and also the objective identification of the situation that justifies the restrictions of access to endoscopy. The utilitarian principles would suggest that the well-being criterion should be given priority, freedom and rights being important only to the extent that they ensure well-being. All health policies use "well-being" as the universally valid ethical currency. The legal framework for establishing the objectives and priorities of the health policy applied during the COVID-19 pandemic is provided by utilitarianism [

27]. Thus a utilitarian approach to the lockdown question may be prepared to override the right to privacy or liberty to protect well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic has indeed had a profound impact on healthcare systems worldwide, affecting not only the management of COVID-19 patients but also the treatment of other routine health conditions. Several key factors contribute to these challenges, particularly in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs): resource constraints, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, financial difficulties, vulnerable populations, lockdowns, travel restrictions and overwhelmed healthcare facilities [

28]. The inability to access hospitals can have profound ethical and social implications by challenging the principles of autonomy and justice in healthcare [

29].

It’s essential to recognize that these changes in the work style of doctors are multifaceted, and their impact on decision making and treatment flexibility can vary based on individual circumstances and healthcare settings. Continuous efforts to address these challenges and strike a balance between efficiency and personalized care are crucial for maintaining the quality of healthcare delivery [

30]. Limited access to trusted healthcare providers had lead to increased anxiety and stress among patients [

31]. Striking the right balance between autonomy, guidelines, and distributive justice is essential for an effective and ethical response to healthcare challenges during a pandemic [

32].

5. Conclusions

This is the first study assessing the post-pandemic burden of COVID-19 –related restrictions in the management of digestive tract cancers in Romania. We searched whether pandemic restrictions had a direct impact in the post-pandemic healthcare burden driven by stage migration and the shifts in morbidity and mortality of digestive tract cancers. Thus, we found that early detection of gastrointestinal malignancies has been severely affected during the pandemic restrictions. This had a direct effect in tumor stage and ECOG status progression. The study illustrates furthermore the impact of deontological bias in favor of utilitarianism and the maximization of the collective good taking precedence over the good of a narrow population group, in need for early diagnosis. Despite the fact that the pandemic is officially over, new cases of COVID-19 are diagnosed every day all over the world, so further research is needed in order to properly address such burden.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board. Approval for Doctoral Research Series, number 34/18.01.2021, issued for Andreea Luiza Palamaru.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented were included in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lui, R.-N. Safety in Endoscopy for Patients and Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tech Innov Gastronintest Endosc. 2021; 23(2): 170-178. [CrossRef]

- Madhav, N.; Oppenheim, B.; Gallivan, M.; Mulembakani, P.; Rubin, E.; Wolfe, N.; Jamison, D.T., Gelband, H.,Horton, S., Jha, P.; et al. Pandemics: Risks, Impacts, and Mitigation. In Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-T.; Hsieh, H.-M.; Chang, Y.-L.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Chen, F.-M. Different impacts of cancer types on cancer screening during COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022, 121, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataga, S.; Tanţău, M.; Cristian, G.; Stanciu, C.; Constantinescu, G.; Goldis, A.; Strain, M.; Eugen, D.; Fraticiu, A.; Saftoiu, A.; et al. ERCP in Romania in 2006; a National Programme seems mandatory. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007, 16, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Harber, I.; Zeidan, D.; Aslam, M.-N. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Possible Consequences. Life (Basel). 2021, 11, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. https://.w. w.w.who.int.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for public?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI8YS6-dfcgQMVyoxQBh1gZAu4EAAYASAAEgJ9JfD_BwE.

- Rothe, C.; Schunk, M.; Sothmann, P.; Bretzel, G.; Froeschl, G.; Wallrauch, C.; Zimmer, T.; Thiel, V.; Janke, C.; Guggemos, W.; et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Stratton, C.-W.; Tang, Y.-W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol, 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative, Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg, 2020, 107, 1097–1103. [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, A.-H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Cogle, C.-R. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Colorectal and Prostate Cancer Screening in a Large U.S. Health System. Healthcare. 2022, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, G.; Cedrone, F.; Di Giovanni, P.; Romano, F.; Staniscia, T. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Oncological Surgery Activities: A Retrospective Study from a Southern Italin Region. Healthcare. 2022, 10, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.-H.; Mainprize, J.-G.; Yaffe, M.-J.; Ruan, Y.; Poirier, A.-E.; Coldman, A.; Nadeau, C.; Iragorri, N.; Hilsden, R.-J.; Brenner, D.-R. The impact of episodic screening interruption: COVID-19 and population-based cancer screening in Canada. J Med Screen. 2021, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, N.; Bassi, A.; Sturgess, R.; Bodger, K. Predictive value of alarm features in a rapid access upper gastrointestinal cancer service. Gut 2005, 54, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.; Larsen, P.-V.; Sondergaard, J.; Elnegaard, S.; Svendsen, R.-P.; Jarbol, D.-E. Specific and non-specific symptoms of colorectal cancer and contact to general practice. Fam Pract 2015, 32, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamarneh, Z.; Symonds, E.-L.; Kholmurodova, F.; Cock, C. Older age, symptoms, or anemia: Which factors increase colorectal cancer risk with a positive fecal immunochemical test? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 35, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, G.-N.; Rockey, D.-C.; Bryson, C.-L.; Weiss, N.-S. Iron deficiency and gastrointestinal malignancy: a population-based cohort study. Am J Med 2002, 113, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardiello, L.; Ferrari, C.; Cameletti, M.; Gaianill, F.; Buttitta, F.; Bazzoli, F.; de’Angelis, G.-L.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, l. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening delay: effect on stage shift and increased mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutikov, A.; Weinberg, D.-S.; Edelman, M.-J.; Horwitz, E.-M.; Uzzo, R.-G.; Fisher, R.-I. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020, 172, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Are, C. COVID-19 Stage Migration (CSM): a New Phenomenon in Oncology? Indian J Surg Oncol. 2021, 12, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.-H.; Mainprize, J.-G.; Yaffe, M.-J.; Ruan, Y.; Poirier, A.-E.; Coldman, A.; Nadeau, C.; Iragorri, N.; Hilsden, R.-J.; Brenner, D.-R. The impact of episodic screening interruption: COVID-19 and population-based cancer screening in Canada. J Med Screen. 2021, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, S.; Stanciu, C.; Cojocariu, C.; Sfarti, C.; Singeap, A.-M.; Girleanu, I.; Cuciureanu, T.; Huiban, L.; David, D.; Zrnovia, S.; et al. The Impact of the CIVID-19 Pandemic on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Activity in a Tertiary Care Center from Northeastern Romania. Healthcare. 2021, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinmouth, J.; Dong, S.; Stogios, C.; Rabeneck, L.; Rey, M.; Dube, C. Estimating the backlog of colonoscopy due to coronavirus disease 2019 and comparing strategies to recover in Ontario. Gastroenterology. 2021, 160, 1400–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, G.; Saibeni, S.; Pellegrini, L.; Picascia, D.; Pace, F.; Schettino, M.; Bezzio, C.; de Nucci, G.; Hassan, C.; Repici, A.; et al. Improvement in appropriateness and diagnostic yield of fast-track endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Northern Italy. Endoscopy. 2021, 53, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F.; Webster, A.; Scott, S.; Emery, J. The Andersen Model of Total Patient Delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012, 17, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, A.; Jones, M.-E.; Broggio, J.; Loveday, C.; Torr, B.; Garrett, A.; Nicol, D.-L.; Jhanji, S.; Boyce, S.-A.; Gronthoud, F.; et al. Collateral damage: the impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Oncol. 2020, 31, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulescu, J.; Persson, I.; Wilkinson, D. Utilitarism and the pandemic. Bioethics 2020, 34, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmi, E.; Chen, Y.; Dourado, I.; Faran-Perach, I.; Furler, J.; Hangoma, P.; Hanvoravongchai, P.; Obando, C.; Petrosyan, V.; Rao, K.-D.; et al. Health equity and COVID-19: Global perspectives. Int J Equity Health. 2020, 19, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancet, T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, D.; Mitra, S. COVID-19 is accelerating the acceptance of telemedicine in India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020, 9, 3785-3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMA says nearly 200 doctors in India have succumbed to COVID-19 so far; requests PM’s attention-The Economic Times [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/ima-says-nearly-200-doctors-in-india-have-succumbed-to-covid-19-so-far-requests-pms-attention/articleshow/77430706.cms?from=mdr.

- Raina, S.-K.; Kumar, R.; Galwankar, S.; Garg, S.; Bhatt, R.; Dhariwal, A.-C.; Christopher, D.-J.; Parekh, B.-J.; Krishnan, S.-V.; Aggarwal, P.; et al. Are we prepared? Lessons from Covid-19 and OMAG position paper on epidemic preparedness. J Fam Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 2161-2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, P.; Kumar, R. Strengthening primary care in rural India: Lessons from Indian and global evidence and experience. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019, 8, 2169-2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).