1. Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health present important challenges to be addressed due to the high prevalence of mental disorders [

1,

2], which has a high impact on the quality of life in the short, medium and long term [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Neuropsychiatric pathologies are the main cause of health problems in this period, representing between 15% and 30% of the years of life lost due to disability or death (YOLS) during the first three decades of life [

7,

8]. The scarce tendency to seek professional help increases the risk of failing in the timely approach, which has important consequences, since it makes it difficult to achieve basic aspects for development [

9,

10,

11]. It is necessary to create accessible and effective interventions, aimed at preventing and promoting mental health in children and young people [

12,

13,

14].

Specifically, early adolescence, understood as the period of life that goes from 10 to 13 years [

15,

16,

17,

18] is a key stage in the development of self-regulatory processes, including attention, emotions and behavior [

19]. Self-regulation skills have been associated with the achievement of greater social and emotional well-being, having a positive impact on academic functioning [

16,

17,

20]. Young people who present deficits in self-regulation skills have a greater risk of presenting physical and mental pathologies in adulthood [

3,

21]. Strengthening self-regulation skills in early adolescence is related to a better prognosis for physical and emotional health in adulthood, as well as greater social and economic achievements [

19].

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) have shown preliminary positive effects on self-regulatory processes in early adolescence. Results show that depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms tend to decrease [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The strengthening of self-regulation skills, specifically in self-regulation responses of attention [

26,

27], emotions [

28,

29] and behavior [

30,

31] have been reported.

Although evidence shows encouraging results regarding the effects of this practice, improving the specificity of the programs, the quality of the research designs [

23,

32] and the variety of modes to deliver interventions (for example, programs carried out 100% online synchronously) [

33] are challenges that need to be addressed. The wide diversity of mindfulness-based programs for children and youth, the heterogeneity of practices they include makes it difficult to distinguish the specific effects of certain practices on defined variables [

23,

33]. This is crucial for developing more precise, effective, and accessible intervention programs. The objective of this research was to evaluate the effect of two MBIs, one focused on classic attentional practices and the other focused on the recognition and expression of emotions, on attentional, emotional, and behavioral self-regulation in early adolescents carried out 100% in online mode.

2. Method

An experimental design with three branches was carried out [

34]. A sample of 70 children was randomized and assigned to three experimental conditions: (1) a program based on mindfulness with focus on attention practices to external and internal stimuli, (2) a program with a focus on the recognition and expression of emotions, (3) control group, waiting list.

2.1. Participants

The sample that participated in this study included boys and girls, between 8 and 12 years old, that assisted to private, subsidized, and public schools in Chile. The distribution of the groups by gender and age is detailed in table 1.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Boys and girls between 8 and 12 years old, belonging to public, subsidized and private schools in Chile. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Children with a current psychopathological clinical diagnosis, without ongoing treatment; (2) Children with some kind of cognitive or motor disability that prevents them from carrying out the evaluation tasks; (3) Children who did not complete the initial evaluation.

The sample size was determined a priori, using the G*Power program version 3.1.9.2, for ANOVA repeated measures intra- and inter-group effect. A medium effect size of 0.25, a statistical power of 0.8, an estimation error of 5% and three measurements per group were considered, yielding n= 36 in total. Considering the probable dropout of some participants, in addition to missing data, a sample size of 72 boys and girls was considered. The budgeted sample size was met, enrolling 74 participants, of which 4 cases were discarded (4 did not meet the minimum number of 6 sessions established in advance). The final sample for analysis then consisted of 70 participants, of which 39 (55.71%) were women and 31 (44.29%) were men. The distribution of the final valid cases is presented in

Table 1.

The group that participated in the intervention with a focus on attention regulation was made up of a total of 24 participants, 14 girls and 10 boys, with an average age of 9.91 years. The group that participated in the program with a focus on emotion regulation was made up of 25 participants, with 13 girls and 12 boys, with an average age of 9.75 years. And the control group contained 21 participants, 12 girls and 09 boys, with an average age of 9.09 years.

2.2. Measures

Children were assessed before starting the intervention and at the end of the 8-week program. The assessed variables were: (1) Mindfulness: evaluated with the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure or CAMM [

35] (2) Emotional regulation: evaluated with the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale or DERS [

36], (3) Behavioral regulation: assessed using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function or BRIEF-2 family form [

37,

38,

39] and (4) Attention: Flanker Task [

40,

41].

2.2.1. Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure, CAMM [35]

The Child and Adolescence Mindful Measure (CAMM) is a self-report test that evaluates trait mindfulness in children and adolescents between 9 and 18 years old [

42]. It has been validated in the Chilean population [

35]. It considers mindfulness as a unidimensional construct, defined as present-focused awareness and the ability to be non-judgmental about internal experiences [

42]. It uses a 5-level Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always) and, with 10 items. The psychometric study applied in Chile and Spain covered a sample of 2,113 Chilean children and adolescents (n = 307 children; n = 687 adolescents) and Spanish (n = 490 children; n = 629 adolescents). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed that validated the unidimensional structure (10 items). Given that the factor loadings of certain items were very low in all samples, it was decided to eliminate three items, generating a new version of the CAMM with only 7 items, showing a reliability of .67 for Chilean children (8 to 12 years) and .85 for Chilean adolescents (13 to 19 years old)[

35]. It should be noted that in this test the questions are posed in a negative way, such as “I think that some feelings I have are bad and I should not have them” so a decrease in the score indicates an increase in the dispositional mindfulness variable.

2.2.2. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, DERS [36]

It is a self-report test that, in its original version for adults, is made up of 36 items with a 6-factor structure [

43]. It is designed to evaluate emotional dysregulation considering the following dimensions: (1) Difficulties in recognizing emotional responses, (2) Difficulties in clarifying emotional responses, (3) Difficulties controlling impulsive behavior facing negative emotions, (4) Difficulties engaging in goal-oriented behaviors facing negative emotions, (5) Non-acceptance of negative emotional responses, (6) Limited access to effective emotional regulation strategies. In adult population, DERS showed an internal consistency index of .93, and test-retest reliability of .88. The internal consistency of each subscale ranged between .80 and .89 [

43]. In the present study, we used the version validated for the Chilean population, whose factor analysis showed a better fit for the 5-factor model with 25 items. The internal consistency of the subscales ranged between .69 to .89, with a general index of .92 for both samples [

36]. An adapted version for adolescents, in which some words were modified based on cognitive interviews and the opinion of expert judges, was used [

44]. Since this test evaluates difficulties in emotional regulation, a decrease in the score indicates an improvement in these skills.

2.2.3. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, BRIEF-2 Family form [37,38]

This instrument evaluates executive functions aimed at guiding, organizing cognition, emotion and behavior in children and adolescents between 5 and 18 years old. There is a family version (for caregivers), and another for teachers. In the present study, the family version was used. This version contains 86 items that indicate various behaviors, which are evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 to 3 (1: never, 3: always). Caregivers are asked to respond thinking about the behaviors observed in their children during the last month. It is made up of 9 subscales: (1) Inhibition, (2) Flexibility, (3) Emotional control, (4) Initiative, (5) Working memory, (6) Planning, (7) Materials organization, (8) Task supervision (9) Self-monitoring. For the present study, the Global Executive Function Index was used, which considers all subscales. The family version showed a test-retest reliability index of .82 [

37,

38]. In its adaptation to the Chilean population [

39] the reliability indices for each of the 9 subscales were: (1) Flexibility, .89; (2) Emotional control, .94; (3) Initiative, .87; (4) Working memory, .94; (5) Planning, .91; (6) Organization of Materials, .92; (7) Task supervision .88; (8) Inhibition, .95; and (9) Self-monitoring, .85. In this test the questions are posed in a negative way, such as “He has explosions of anger.”, so a decrease in the score indicates an increase in the behavioral self-regulation variable.

2.2.4. Flanker Task [40,41]

Flanker Task is a computerized test, designed in 1970 by Eriksen and Eriksen. It is assesses the components of the tripartite model of attention, which is consistent with what was proposed by Petersen and Posner [

45]: alertness (state of vigilance and preparation to respond to environmental stimuli), orientation (ability to direct and limit attention to a specific stimulus) and conflict monitoring (prioritizing the localization of attention between competing stimuli) [

26]. The test is carried out in four moments: sample test, to ensure that the child understands the instructions, and three effective tests. The instructions consist of observing the screen, on which 5 letters will appear simultaneously. The person must focus and respond based on the central letter. If this center letter corresponds to the letters X or C, the person must press A in the keyboard. If the center letter on the screen corresponds to the letters V or B, the person must press the L key. The center letter can be surrounded by similar letters (this would correspond to a congruent stimulus, for example, BBBBB), or, it can be surrounded by different letters (this would be an incongruent stimulus, for example, XXBXX). The time and accuracy of the response can be affected by the congruency or incongruity of the stimulus, as it is surrounded by irrelevant information that must be attended to and discarded to respond [

40,

41]. For the present study, the PsyToolKit platform (

https://www.psytoolkit.org/experiment-library/flanker.html#_introduction) was used.

This test provides four measures regarding the self-regulation of attention: (1) response time to a congruent stimulus; (2) response time relative to incongruent stimulus; (3) percentage of error in responses with a congruent stimulus; (4) percentage of error in responses with incongruent stimuli. For the present study, we consider the percentage of error versus incongruent stimulus as a measure of attention, since this measure allows us to evaluate the three components of attention relevant to this study, which are alertness, orientation, and conflict monitoring [

27,

46].

2.3. Interventions

The kind of treatment was defined as independent variable, which consisted of three options: (1) treatment based on mindfulness with a focus on the regulation of attention (2) treatment based on mindfulness with a focus on the regulation of emotions, (3) group passive control or waiting list. The design of both programs was carried out with the supervision of two independent experts, who evaluated the exercises included in each program based on their relevance to developing the regulation of attention, emotions and behavior.

Regarding the instructors, a selection and training process was carried out. Recruitment was by convenience, based on inclusion criteria. The criteria were: (1) People with verifiable Mindfulness training; (2) People with experience working with children. The 3 selected instructors met these criteria. One of them was a child and adolescent psychiatrist, another was a child and adolescent psychologist and the third, a primary teacher. They participated in the Instructor Training Program, which had 8 sessions of 2 hours each. This program included the first-person experience of the 8 1-hour sessions with all the practices for children included in both interventions, in addition to theoretical and empirical foundations on mindfulness. A manual was prepared for the instructors detailing the curriculum for each session, to facilitate fidelity to the original design.

Before starting the interventions, a manual and a box of specific material were sent by mail to each boy and girl, as well as a set of audios with exercises to practice between sessions. The maximum number per group was 12 children, with two instructors per group. The main researcher was one of the instructors, accompanied by one of the 3 trained instructors. For each session, a Google Meet link was sent weekly to the email of each parent, through which the boys and girls accessed the synchronous session from their homes.

2.3.1. Intervention 1: Program Based on Mindfulness with a Focus on Attention

This curriculum was designed selecting exercises aimed at developing attention, whether to external stimuli (sounds, flavors, colors, etc.), or internal stimuli (sensations, emotions, thoughts, breathing). This intervention lasted 8 weeks, with a 1-hour session per week. The name given to this attention-focused program was “Monkey Mind, Where Are You?” A summary of the exercises included in each session is described in table 2.

2.3.2. Intervention 2: Mindfulness-Based Program with a Focus on Emotions

This program was designed choosing exercises aimed at developing emotional regulation, such as: observing and identifying emotions in the body, describing these emotions, observing and describing thoughts associated with emotions, and describing behaviors that arise with emotions, in addition to exercises of empathy and compassion. The program lasted 8 weeks, with a 1-hour session per week. The intervention was also manualized, exercises were given to do at home, supported by audios and concrete material. The name given to this program with a focus on attention was “I am a Dragon, what can I do with my fire?”. A summary of the program curriculum is detailed in

Table 3.

2.4. Procedure

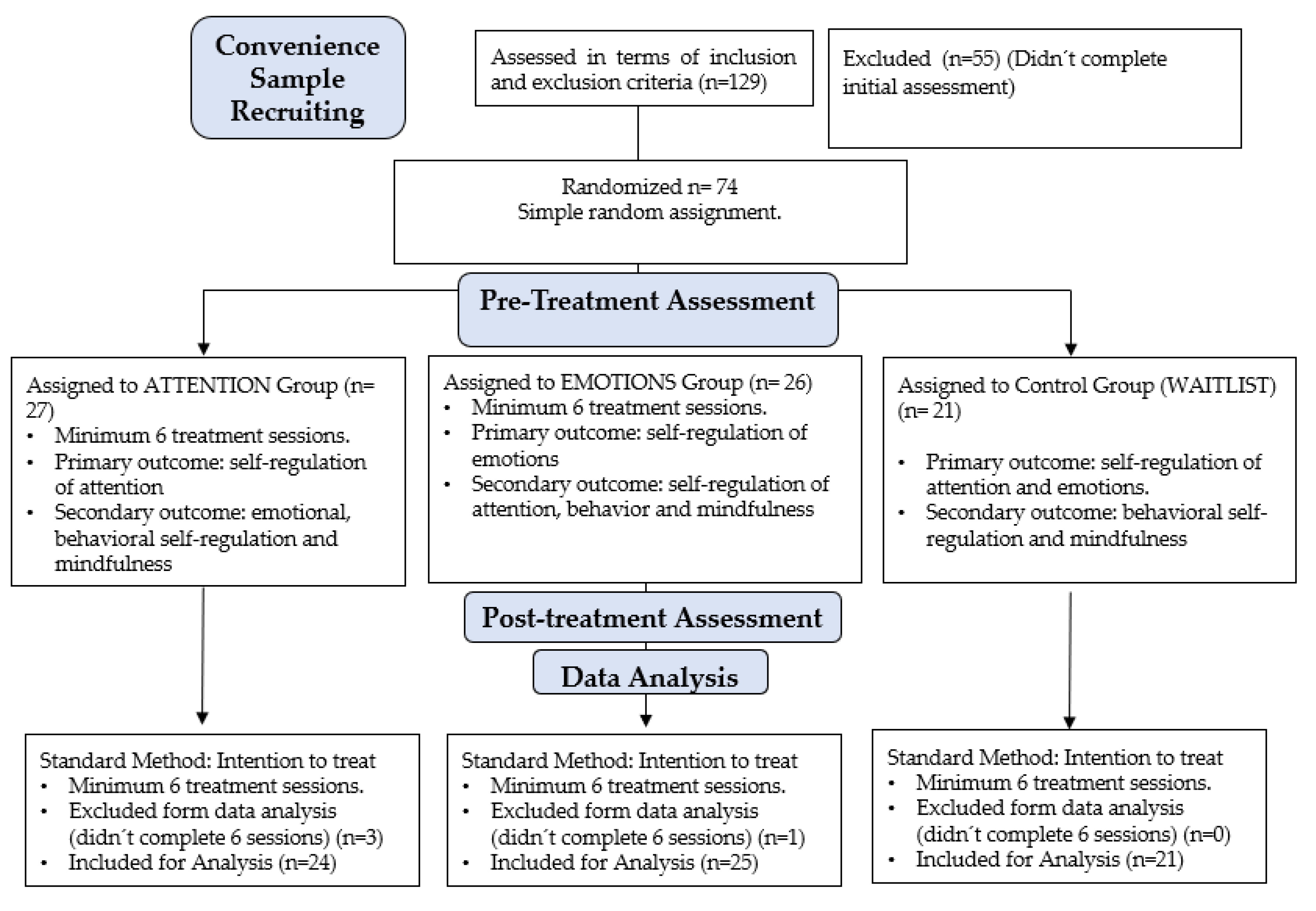

A non-probability convenience sample was carried out. The recruitment was done amid the COVID-19 pandemic through social networks. Once contact was established with the caregivers, information was sent via email. Based on the sociodemographic information and background of the participants, an analysis was carried out based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned to each of the three study conditions through a manual lottery. The initial equivalence of the groups in terms of gender, age, and type of schools (private, public, or subsidized) was ensured. The above can be seen in the following flow chart (

Figure 1)

2.4.1. Data Analysis

The analysis of the results began, obtaining the main descriptive statistics of the variables. To answer the research questions, linear mixed models were used, considering treatment (condition) and time as fixed effects, while within the random effects a random intercept was considered for each subject. This technique was selected since it is appropriate to have correlations within clusters with common characteristics [

47], in this case, each study participant. To analyze the influence of the factors, F tests were carried out to test the significance of each fixed effect within the total model [

48], considering the Satterthwaite approximation for obtaining degrees of freedom, controlling for age and gender variables.

If the interaction effect was significant, the marginal means (emmeans) at each level were analyzed to compare and explore in more detail the significance of these differences, for which the Bonferroni significance correction was used.

The interaction effects between the variables were analyzed, specifically, the existence of an interaction between the variable mindfulness, and self-regulation of attention, emotions, and behavior. If no interaction effect was found, the main effects were analyzed in order to check whether both time or group condition had any significant effect. The analyzes described were performed using the R program version 4.1.0.

3. Results

Descriptive analysis results are summarized on

Table 4.

Results will be described for each variable.

3.1. Mindfulness

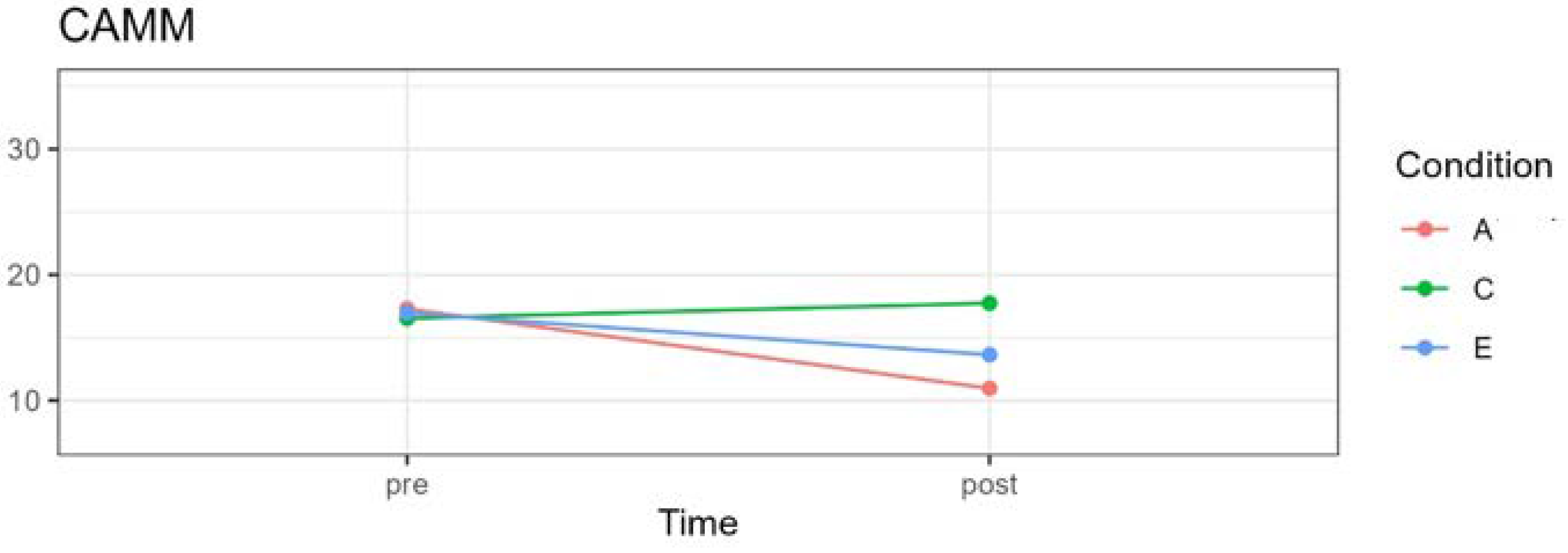

A significant interaction effect between time and treatment was observed

F (2;59.21) = 24.64, p <0.001, in addition to a significant main effect for time with

F (1;65.58) = 37.54, p <.001. This is not the case for the three experimental conditions, with

F (1;59.92) = 2.53, p = 0.08. The following graph (

Figure 2) shows the means for each condition in pre- and post-treatment times.

No significant differences were observed between the 3 experimental groups in the pre-treatment evaluation. Significant differences are observed in the attention condition in the pre-post times

t (65.4) = 8.16, p <.0001 and emotion

t (65.8) =4.05, p=0.0001, This difference can be checked with the mean scores shown in

Table 4. For the control group, no significant differences are observed between the pre and post times with

t (63.1) =-1.50, p=0.137, showing a slight increase in the means.

3.2. Behavioral Self-Regulation

A significant interaction effect of time and condition was observed, with F (2;58.29) =3.88, p=0.026, in addition to a significant main effect for time, with F (1;66.34) = 5.83, p= 0.018. Experimental condition didn’t show significance, with F (2;59.22) = 2.09, p=0.13. The following graph (

Figure 3) shows the means for each condition in pre- and post-treatment times.

No significant differences are observed for the three experimental conditions in the pre-treatment time. For the Attention group, a significant pre and post effect is observed, with t (66.3) =2.72, p=0.0083, The same occurs with the Emotion group, in which a significant pre-post effect is observed, with t (66.7) =2.27, p=0.026. For both experimental conditions, a decrease in scores is observed in the mean table (

Table 4) between the pre and post times. In the control group, no significant changes were observed, with t (63.4) = -0.78, p = 0.437, maintaining a similar mean of the scores obtained in both times.

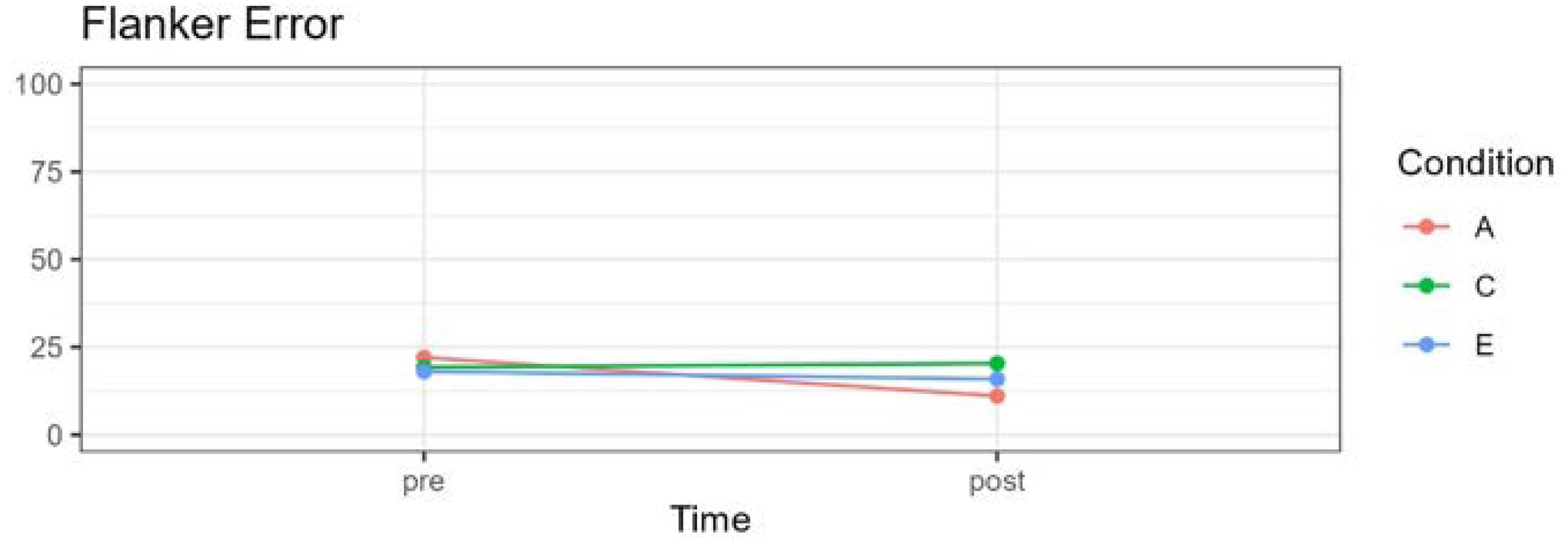

3.3. Attention Self- Regulation

Self-regulation of attention was evaluated using the computerized Flanker Task test considering the measurement of percentage error in responses to incongruent stimuli. A significant interaction effect is observed F (2;57.26) = 3.98, p = 0.023. No significance is reported for time with F (1;61.36) = 3.27, p=0.075, nor for the three experimental conditions with F (2;58.13) =0.07, p=0.930.

The following graph (

Figure 4) shows changes in the percentage of errors when faced with incongruent stimuli, evaluated using the Flanker test.

No significant differences were observed between the groups in the pre-treatment time. A significant effect is observed between pre and post times only for the Attention group t (63.4) =3.271, p=0.0017, For both the Emotion and Control groups, no significant differences are observed with t (62.4) =0.373, p=0.710 and t (60.8) =-0.456, p=0.650. This is consistent with what can be seen regarding the means in

Table 4, for the Attention group they decrease between the pre and post times in a pronounced manner. The Emotion group decreases slightly while the control group increases.

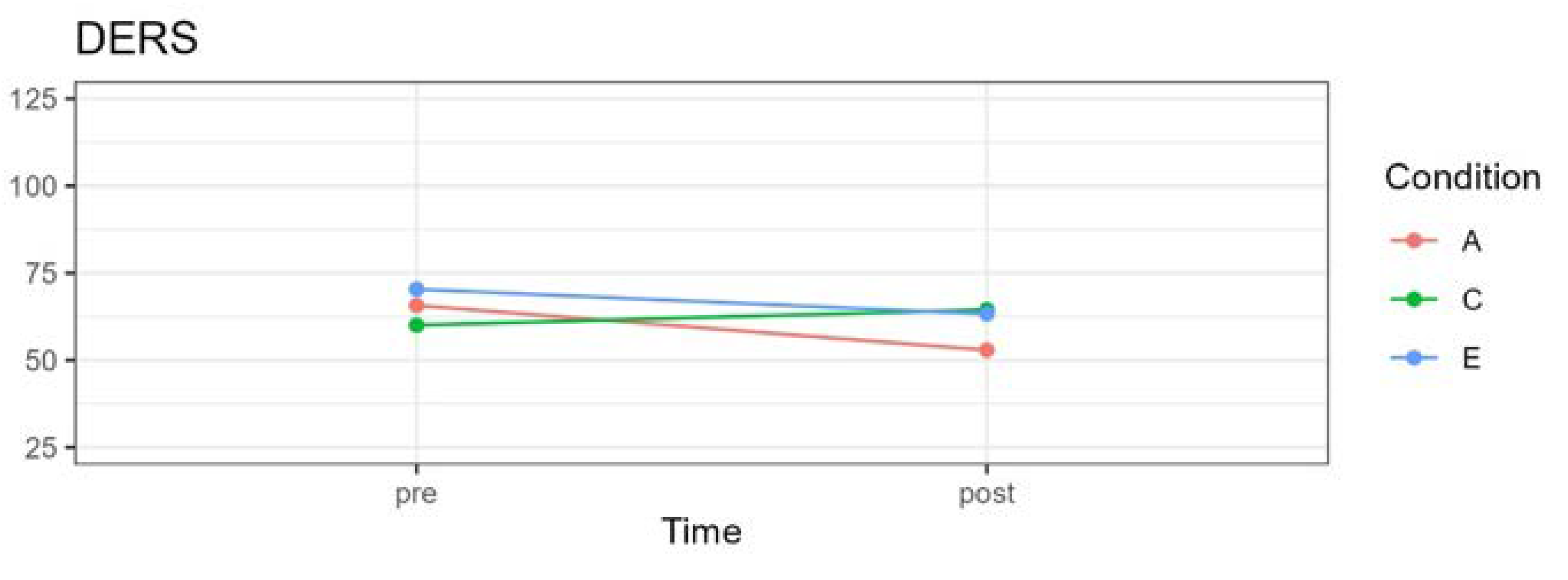

3.4. Emotional Self- Regulation

A significant interaction effect was observed between time and treatment F (2;57.81) = 10.57, p <0.001, and a significant main effect for time with F (1;63.13) = 12.38, p <.001; This is not the case for the three experimental conditions with F (2;58.99) = 2.14, p = 0.126. The following graph (

Figure 5) shows the changes in the emotional self-regulation variable.

No significant differences were observed between the 3 experimental groups in the pre-treatment evaluation. Significant differences are observed between the pre and post times for the attention condition t (63.8) =4.99, p< .0001 and for the emotion condition t (64.0)=2.58 p= 0.012, which effectively decreased their means as shown in table 4. No significant changes were observed for the control group, which slightly increases the value of its mean.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of two programs based on Mindfulness, one with a focus on attention and the other with a focus on emotions, on the levels of mindfulness, self-regulation of attention, emotions and behavior in boys and girls between 8 and 12 years. Results indicate that both children who participated in the attention-focused program and children who participated in the emotion-focused program increased their mindfulness, behavioral and emotional regulation scores. Only children who participated in the program with a focus on attention improved their ability to regulate attention, showing a significant decrease in the error percentage for incongruent stimuli. Both, children who participated in the group with a focus on emotions and those in the control group maintained their error percentage rates.

4.1. Mindfulness

Results show that both programs favor mindfulness trait development. This is consistent with previous studies, regarding the effects of basic body attention and breathing exercises on trait mindfulness in the child and adolescent population [

33,

49]. Likewise, the results are consistent with the evidence related to the structure of the program, specifically its duration and frequency. In this case, both programs lasted 8 weeks with a weekly session of one hour, a decision that was made based on the effectiveness of existing models [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Based on the results obtained, we can affirm that the proposed structure (8 weeks, weekly frequency and 60-minute sessions), in addition to the inclusion of the core mindfulness practices detailed in each curriculum, is effective for mindfulness development.

4.2. Behavioral Self-Regulation

Results show an increase in this skill for both the children who participated in the program with a focus on attention and emotions, with no changes for the control group. This ability was evaluated by parents and caregivers using the BRIEF-2 Family version [

39,

56,

57]. For the analysis, the Global Index of Executive Function was considered, which is a score that summarizes the nine clinical scales of the BRIEF-2 (Inhibition, Flexibility, Emotional Control, Initiative, Working Memory, Planning and Organization, Self-Monitoring, Supervision of your task and Organization of Materials). The increase observed in these functions by parents in the participating children is consistent with previous studies. Research points out the positive effect of practicing mindfulness on executive functions in the child and adolescent population [

58,

59,

60], specifically on response inhibition [

61] and self-monitoring [

62]. However, there is controversy in this regard, as not all mindfulness-based programs would produce significant changes in these functions [

63]. Based on this study, we can conclude that the formula of 8 sessions, once a week, with sessions of 60 min. of duration that include basic mindfulness exercises, produce significant changes in the behavioral self-regulation of boys and girls from 8 to 12 years old. Future studies will be necessary to determine the specific exercises and dose of practice is required to produce changes in these skills at other stages of development.

4.3. Attentional Self- Regulation

Results show that only children exposed to the program with a focus on attention improved self-regulation of attention, showing a decrease in the percentage of errors for incongruent stimuli. The children who participated in the program with a focus on emotions and those who participated in the control group did not show significant changes in this indicator. A possible explanation is related to the types of practices contained in each program. In the program with a focus on attention, all 8 sessions exclusively included classic mindfulness practices, called contemplative practices (such as conscious breathing, conscious movement, sitting meditation, body scan). In the program with a focus on emotions, these classic mindfulness practices are included in 3 sessions (1, 2 and 8), and then practices focused specifically on the awareness and expression of emotions and also generative practices. The latter seek to generate specific states such as empathy or compassion [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68].

4.4. Emotional Self-Regulation

Results indicate that both, children who participated in the program with a focus on attention and the children who participated in the program with a focus on emotions improved their emotional regulation scores, unlike the children in the control group. The fact that children who participated in the program that focused solely on attention improved their emotional self-regulation skills is interesting to consider.

Self-regulation is defined as the ability to monitor and control one's cognitions, emotions, and behavior in pursuit of goal achievement, or adapting to cognitive and emotional demands of specific situations [

69]. These skills would be interrelated, which is consistent with the model proposed by Tang, Hölzel [

27] which shows the interrelationship between attentional and emotional regulation and self-awareness. Specifically in the case of attentional regulation, there is evidence that indicates it as a critical component of self-regulation, specifically in early adolescence [

69,

70]. Attentional processes play an important role in self-regulated action and may be especially important in the regulation of emotions in infants, children, and adolescents [

16,

17]. Based on this, the results of this study show the impact of strengthening attentional regulation as a foundation to facilitate emotional regulation at this critical developmental period [

20,

27,

46,

71].

From an evolutionary perspective, we could hypothesize that the balance and influence between the variables of regulation of attention, emotions and behavior can be dynamic throughout development [

15,

72,

73] which is relevant for decision making regarding child and adolescent interventions. It is crucial to consider the dynamism of the evolution and development of the life cycle, to determine which skill can be a “meta-skill” at each stage of development. In the case of the present study, which includes boys and girls between 8 and 12 years old, it seems that classic contemplative practices, which include paying attention to internal and external stimuli, would facilitate not only the regulation of attention, but also the self-regulation of emotions. emotions and behavior.

4.5. Limitations

The present study has both methodological and conceptual limitations. Regarding methodological limitations, it is important to point out the context. The COVID 19 pandemic involved a series of difficulties that made changes necessary in the way we intervene and evaluate children. In the first instance, the intervention would be carried out in schools face to face, which had to be modified to be carried out exclusively online. From this, the following limitations arise: (1) The online application of all the evaluations could have influenced the children's reading comprehension regarding the self-assessment tests. Although a review was previously carried out on the understanding of the language used in the tests, and we asked parents to be available to solve children doubts, we did not have greater control over it, therefore, the reading comprehension factor of the items could have influenced the results. (2) The sample size in the present study is small, so it will be a factor to consider in future studies, (3) A follow up, after finishing the intervention would be necessary to include in future studies.

4.6. Future Research

Future research can be carried out to generate accessible and lower-cost proposals for child and adolescent population, and, to adjust interventions for specific groups.

Regarding universalization, we need to move towards preventive and universal models [

74,

75,

76]. With the present study, this possibility is not limited to face-to-face interventions, but there is preliminary evidence of the effects of programs taught 100% online. This opens the possibility of universalizing this kind of practices, given that most interventions for this population continue to be exclusively face-to-face [

33]. Future research could investigate more deeply the effects of various modalities: 100% in-person, hybrid modality, 100% synchronous online modality. It also opens the possibility of investigating the effect of e-learning modalities, the eventual gamification that has already been included in the educational field [

77,

78,

79], or the use of immersive practice technologies that can make mindfulness closer and more accessible, which has already been incorporated into the clinical context [

80].

On the other hand, the present study was carried out mainly on non-clinical sample. It will be necessary to specify the effects of this kind of programs in children with diagnoses related to neurodevelopmental disorders (such as ADHD, ASD, SLI), as well as boys and girls with internalizing (anxious, depressed) and externalizing symptoms (oppositional defiant disorder) [

81,

82]. It will also be necessary to adapt this type of interventions to children with disabilities and evaluate their effects both with respect to self-regulation and mental health skills, such as children who are blind, deaf or with permanent motor difficulties, which has been investigated in adult population [

83,

84,

85].

It´s also necessary to evaluate the effect of on younger children, and in elder adolescents. A conceptual definition of mindfulness that can be operationalizable for every period, that can give coherence to the trajectory of mindfulness development throughout the life cycle is needed [

33]. This is crucial to avoid interventions that are atomized and disconnected from each other.

5. Conclusions

The present study was designed to assess the effectiveness of two programs based on mindfulness over trait mindfulness and self-regulation of attention, emotions and behavior in boys and girls between 8 and 12 years old.

Based on the present study, the main conclusions are presented below:

1) Results show that both interventions generate an improvement in trait mindfulness or dispositional mindfulness.

2) Both, the program with a focus on attention and the program with a focus on emotions showed significant changes in the regulation of emotions and behavior.

3) The effect of the programs on self-regulation of attention was diverse. Only children who participated in the program with a focus on attention showed a significant change in the precision of their responses, decreasing the percentage of errors for incompatible stimuli in a significant way.

4) We can conclude that both programs can be a contribution to strengthening self-regulation skills of emotions and behavior in boys and girls between 8 and 12 years old, with the program focusing on attention also being effective in terms of attentional self-regulation.

Author Contributions

B.P. designed the study and coordinated the data collection. B.P., C.O., I.B. and W.P. contributed to the data analyses and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.O. and W.P. declare having received financial support from the National Agency forResearch and Development (ANID)/International Cooperation Program/Project MEC80180087 of the Chilean Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge, and Innovation. B.P. declares having received funding from Doctoral Scholarship n◦ 21180390 from ANID Institutional Review Board.

Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Concepción, code 01122018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the caregivers, and informed assent was obtained from all the of minors involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author to get the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vicente, B. , et al., Salud mental infanto-juvenil en Chile y brechas de atención sanitarias. Rev. Médica Chile 2012, 140, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, B., S. Saldivia, and R. Pihán, Prevalencias y brechas hoy: salud mental mañana. Acta Bioethica 2016, 22, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anto, S.P. and C. Jayan, Self-esteem and emotion regulation as determinants of mental health of youth. SIS J. Proj. Psychol. Ment. Health 2016, 23, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Arango, C. , et al., Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, W.T. , The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 36, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C. , et al., Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baranne, M.L. and B. Falissard, Global burden of mental disorders among children aged 5–14 years. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2018, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C. , et al., Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.K. , et al. , Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: an update from ten states and the District of Columbia 2010,American journal of preventive medicine 2015, 48, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luby, J.L. , et al., Association between early life adversity and risk for poor emotional and physical health in adolescence: A putative mechanistic neurodevelopmental pathway. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 1168–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A. , Future directions in childhood adversity and youth psychopathology, in Future Work in Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2018, Routledge. p. 345-366.

- Errázuriz, P. , et al., Financiamiento de la salud mental en Chile: una deuda pendiente. Rev. Médica De Chile 2015, 143, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J. , et al., Treated prevalence of and mental health services received by children and adolescents in 42 low-and-middle-income countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúñiga-Fajuri, A. and M. Zúñiga, Propuestas para ampliar la cobertura de salud mental infantil en Chile. Acta Bioethica 2020, 26, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourneret, P. and V. des Portes, Developmental approach of executive functions: From infancy to adolescence. Arch. De Pediatr. : Organe Off. De La Soc. Fr. De Pediatr. 2017, 24, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, M.M. , et al. Development and self‐regulation. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science 2015, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, M. , et al., Self-regulation. Handbook of life course health development 2018, 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, X. , Adolescencia:¿ una etapa problemática del desarrollo humano? Revista Ciencias de la Salud 2019, 17, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunhoven, R.J. and D. Dorjee, How does mindfulness modulate self-regulation in pre-adolescent children? An integrative neurocognitive review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, M.R. I. Posner, and M.K. Rothbart, The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation, in Measurement of Executive Function in Early Childhood. 2016, Psychology Press. p. 573-594.

- Cavicchioli, M. , et al., Persistent Deficits in Self-Regulation as a Mediator between Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Substance Use Disorders. Subst. Use Misuse 2022, 57, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, C.A. , Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, D.A. , et al., Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology 2017, 63 (Supplement C), 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingbeil, D.A. , et al., EFFECTS OF MINDFULNESS-BASED INTERVENTIONS ON DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR: A META-ANALYSIS OF SINGLE-CASE RESEARCH. Psychol. Sch. 2017, 54, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoogman, S. , et al. , Mindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 290–302. [Google Scholar]

- Felver, et al. , The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Children’s Attention Regulation. J. Atten. Disord. 2014, 21, 872–881. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Hölzel, and Posner, The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, A. , et al., Observing nonreactively: A conditional process model linking mindfulness facets, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 165, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, J. , et al., Mindfulness and emotion regulation—an fMRI study. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 9, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonert-Reichl, et al. , Promoting children’s prosocial behaviors in school: Impact of the “Roots of Empathy” program on the social and emotional competence of school-aged children. Sch. Ment. Health 2012, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, et al. , Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felver, et al. , A systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions for youth in school settings. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B. , et al. , Systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions in child-adolescent population: A developmental perspective. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2022, 12, 1220–1243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ato, M., J. J. López, and A. Benavente, Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. De Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rubio, C. , et al., Validation of the Spanish Version of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) with Samples of Spanish and Chilean Children and Adolescents. Mindfulness, 2019.

- Guzmán-González, M. , et al., Validez y Confiabilidad de la Versión Adaptada al Español de la Escala de Dificultades de Regulación Emocional (DERS-E) en Población Chilena. Ter. Psicológica 2014, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G.A. , et al., TEST REVIEW Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Child Neuropsychol. 2000, 6, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, G.A. , et al., Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a Clinical Sample. Child Neuropsychol. 2002, 8, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Salas, C. , et al., Bifactor Modeling of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a Chilean Sample. Vol. 122. 2016.

- Ridderinkhof, K.R. , et al. , The arrow of time: Advancing insights into action control from the arrow version of the Eriksen flanker task. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 2021, 83, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, B., F. Rist, and U. Mattler, N200 in the flanker task as a neurobehavioral tool for investigating executive control. Psychophysiology 1996, 33, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, L.A., R. A. Baer, and G.T. Smith, Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessment 2011, 23, 606–614. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L. and L. Roemer, Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanadel, C. , et al., Association of Emotion Regulation and Dispositional Mindfulness in an Adolescent Sample: The Mediational Role of Time Perspective. Children 2023, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.E. and M.I. Posner, The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, et al. , Developing attention: behavioral and brain mechanisms. Advances in Neuroscience 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S.W. and A.S. Bryk, Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. 2002: sage.

- Galecki, A. and T. Burzykowski, Linear mixed-effects model. 2013: Springer.

- Emerson, L.-M. , et al., Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, L. , et al., Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, A. , A still quiet place: A mindfulness program for teaching children and adolescents to ease stress and difficult emotions. 2014: New Harbinger Publications.

- Saltzman, A. , A Still Quiet Place for teens: A mindfulness workbook to ease stress and difficult emotions. 2016: New Harbinger Publications.

- Saltzman, A. , Still Quiet Place: Sharing mindfulness with children and adolescents, in Handbook of Mindfulness-Based Programmes. 2019, Routledge. p. 267-281.

- Snel, E. , Tranquilos y atentos como una rana: La meditación para niños... con sus padres. 2013: Editorial Kairós.

- Uşakli, H. , Selected, adopted and implemented social-emotional learning program: The Kindness Curriculum for kids. Educ. Chall. 2021, 26, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, T.G. , et al., Psychometric characteristics of the BRIEF scale for the assessment of executive functions in Spanish clinical population. Psicothema 2014, 26, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, S.C., G. A. Gioia, and P.K. Isquith, BRIEF-SR: Behavior rating inventory of executive function--self-report version: Professional manual. 2004: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Quach, D., K.E. Jastrowski Mano, and K. Alexander, A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining the Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on Working Memory Capacity in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 2016, 58, 489–496. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L. , et al., Enhancing executive function skills in preschoolers through a mindfulness-based intervention: A randomized, controlled pilot study. Psychol. Sch. 2018, 55, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D. , et al., Mindfulness Plus Reflection Training: Effects on Executive Function in Early Childhood. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lassander, M. , et al., The Effects of School-based Mindfulness Intervention on Executive Functioning in a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Developmental Neuropsychology 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K. and D. Seiden, Effects of a brief mindfulness curriculum on self-reported executive functioning and emotion regulation in Hong Kong adolescents. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberger-Truelove, M.E. , et al., Self-regulatory growth effects for young children participating in a combined social and emotional learning and mindfulness-based intervention. J. Couns. Dev. 2018, 96, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Maynar, M. and C.K. Germer, Autocompasión en Psicoterapia y el Programa Mindful Self Compassion:¿ Hacia las Terapias de Cuarta Generación? De Psicoter. 2016, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bluth, K. and K. D. Neff, New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity 2018, 17, 605–608. [Google Scholar]

- Brito-Pons, G., D. Campos, and A. Cebolla, Implicit or explicit compassion? Effects of compassion cultivation training and comparison with mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C. and K. Neff, Mindful self-compassion (MSC). Handbook of mindfulness-based programmes: Routledge 2019,357-67.

- Neff, K. and M. C. Knox, Self-compassion. Mindfulness in positive psychology: The science of meditation and wellbeing 2016, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fjell, A.M. , et al., Multimodal imaging of the self-regulating developing brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 19620–19625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A. , et al. , Multidisciplinary perspectives on attention and the development of self-regulation. Progress in neurobiology 2007, 82, 256–286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-Y., R. Tang, and M.I. Posner, Mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation and reduces drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 163, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burman, E. , Deconstructing developmental psychology. 2016: Routledge.

- Zeman, J. , et al., Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2006, 27, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council, N.R. , and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities [Internet]. O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Preventing mental, emotional and behavioural disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. National Academic Press (US), 2009.

- Dowdy, E., K. Ritchey, and R. Kamphaus, School-based screening: A population-based approach to inform and monitor children’s mental health needs. Sch. Ment. Health 2010, 2, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatica-Saavedra, M., B. Vicente, and P. Rubí, Plan nacional de salud mental. Reflexiones en torno a la implementación del modelo de psiquiatría comunitaria en Chile. Rev. Médica De Chile 2020, 148, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponetto, I., J. Earp, and M. Ott. Gamification and education: A literature review. in European Conference on Games Based Learning. 2014. Academic Conferences International Limited.

- Dicheva, D. , et al., Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nah, F.F.-H. , et al. Gamification of education: a review of literature. in HCI in Business: First International Conference, HCIB 2014, Held as Part of HCI International 2014, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, -27 2014,Proceedings 1. 2014, Springer. 22 June.

- Gromala, D. , et al. The virtual meditative walk: virtual reality therapy for chronic pain management. in Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M. , Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications. 2009: University of Vermont, Research Center of Children, Youth & Families.

- Achenbach, T.M. , et al., Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehnabi, A., H. Radsepehr, and K. Foushtanghi, The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on social anxiety of the deaf. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Public Health.

- Nejati, V. , et al., Mindfulness as effective factor in quality of life of blind veterans. Iran. J. War Public Health 2011, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani, M. and G. Jabari, Evaluation of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the quality of life and mental health of mothers of deaf children. J. Mod. Rehabil. 2017, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).