1. Introduction

Tackling the development of muscle diseases is central to global policies for the promotion of a healthy lifestyle [

1]. Adverse muscle changes can accumulate over lifetime as a result of decreased hormones, increases in inflammation, reduction in activity, and inadequate nutrition [

2]. Sarcopenia is a muscle disease characterized by the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle function common among adults of older age but can also occur earlier in life [

3]. According to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), the diagnosis of sarcopenia is confirmed when in addition to low muscle strength, low muscle quantity or quality is present [

3]. Echo intensity (EI) as determined by B-mode ultrasound is an accepted marker for muscle quality [

4,

5]. Echo intensity has been associated with maximal strength, power, and functional performance [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, the EI can also detect neuromuscular disease progression [

9,

10]. For example, high EI values reflect fibrotic muscles that are rich in fat infiltration as observed in Duchenne muscular dystrophy [

11]. As such, EI may be a valuable add-on method to the screening and diagnosis, as well as the monitoring of neuromuscular diseases [

12,

13].

It is common practice in diagnostic ultrasound to adjust image parameter settings to achieve the best possible image quality [

14]. However, since standardized procedures for quantifying muscle quality are lacking, comparing EI results between studies poses challenges [

15]. As a result, normal values for EI of the quadriceps muscle vary largely between studies, partly due to differences in parameter settings [

16,

17,

18]. Indeed, in order to facilitate the comparison of EI values between clinicians, more recently it has been suggested to control settings for US parameters such as gain and depth [

19,

20,

21]. As relatively small increases (10 dB) in gain or depth (1 cm) significantly increase the EI value of the examined muscle, it has been recommended to fix both gain and image depth within and between individuals when evaluating EI [

21].

However, the influence of other settings (beyond gain and depth) on measures of muscle quality is unknown so far. Based on a previous image optimization study, highlighting the most common parameters among US systems, we hypothesized that dynamic range, gray map, line density, persistence, and IClear could all potentially affect the EI outcome [

14]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to assess the influence of common US parameter settings on EI values using a standardized approach in a sample of middle-aged healthy persons.

2. Materials and Methods

Twenty-one healthy volunteers were enrolled in this study (14 men and 7 women). Prior to participating, all volunteers were instructed about the aims of the study and signed a written informed consent. All participants were adults aged 18 years or older, not affected by neuromuscular diseases, and in general good health. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Brussels (B.U.N. 1432020000335).

2.1. Ultrasound Parameters

We investigated five US parameters that may influence EI: dynamic range (DR), gray map (GM), line density (LD), persistence (PERS) and IClear (IC) [

14]. Dynamic range defines the echo strengths shown on the monitor. A low DR results in a more ‘black and white’ view, with a higher contrast enabling the detection of structure boundaries. On the other hand, a higher DR scan appears brighter and softer, giving more information about the echo patterns. The second parameter was the gray map, determining which ultrasonic signal is displayed in which grayscale (how bright/dark). Typically, an S-shaped curve is used instead of a linear correlation. This increases contrast at intensities that often occur in US images. The third parameter analyzed was line density, which determines the quality and information in the image. A change in LD impacts the frame rate. Higher LD results in an automatic lowering of the frame rate. Levels available on the machine were ‘L’ (low), ‘M’ (medium), ‘H’ (high), and ‘UH’ (ultra-high). The fourth parameter of interest was persistence, which defines how much of the previous image is taken over into the current frame. This makes the resulting image appear smoother and less wobbly. A high persistence is useful for long-time scans but might be more difficult to use for fast-moving structures such as the heart. Persistence increase may lead to signal missing. The fifth parameter was IC, whose function is to increase the image profile, so as to distinguish the image boundaries.

2.2. Scanning Procedure and Image Analysis

Each volunteer was asked to lay on a physiotherapy treating table, in a supine position, hips and knees slightly flexed with a 10 cm thick knee roll placed under them, heels resting on the table. This position was maintained for the entire procedure. Participants had been instructed not to exercise the day of the examination. As it has previously been reported that anterior thigh and abdominal muscles are the first muscles affected by aging, we scanned the rectus femoris (RF), gracilis (GR) and the rectus abdominis (RA) muscles

[22,23]. For the RF and GR muscles a horizontal line was drawn at 50% between the greater trochanter of the femur and the lateral knee joint line of the right thigh [

24]. For the RA muscle a horizontal line starting from the linea alba was drawn in the right hemisphere of the body, 2 cm above the umbilicus [

25]. A Mindray M7 premium US portable machine (© Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics CO., LTD., Shenzhen, China) equipped with a linear 5.0-10.0 MHz transducer was used to perform the scanning sessions using a B-Mode setup. Images were acquired using an EFOV ultrasound method, which gathers together a sequence of B-Mode images taken from a continuous US scan, with high reliability

[26,27]. All the scans were performed from medial to lateral.

The basic parameter settings for the scans were as follows: gain 60 dB, depth 6.5 cm, and frequency 10 MHz. For the other parameters, the default setup was DR 65, GM 2, LD M, PERS 0, and IC 0 (

Table 1). This default setup was chosen based on the work of Steffel et al. [

20] who assessed the impact of changing the gain on EI. At this point, several combinations of settings were applied as shown in

Table 1. Each scan was performed by changing the image settings, one at a time, keeping the other parameter settings constant. The procedure was the same for all muscles examined. A total of 16 transverse EFOV scans were performed for each muscle, totaling 48 scans for each participant. All the scans were made by the same trained examiner. Special care was taken to put enough coupling gel between the skin and the transducer, to use minimal constant pressure on the skin, and to keep the transducer perpendicular to the surface in order to avoid image disturbances.

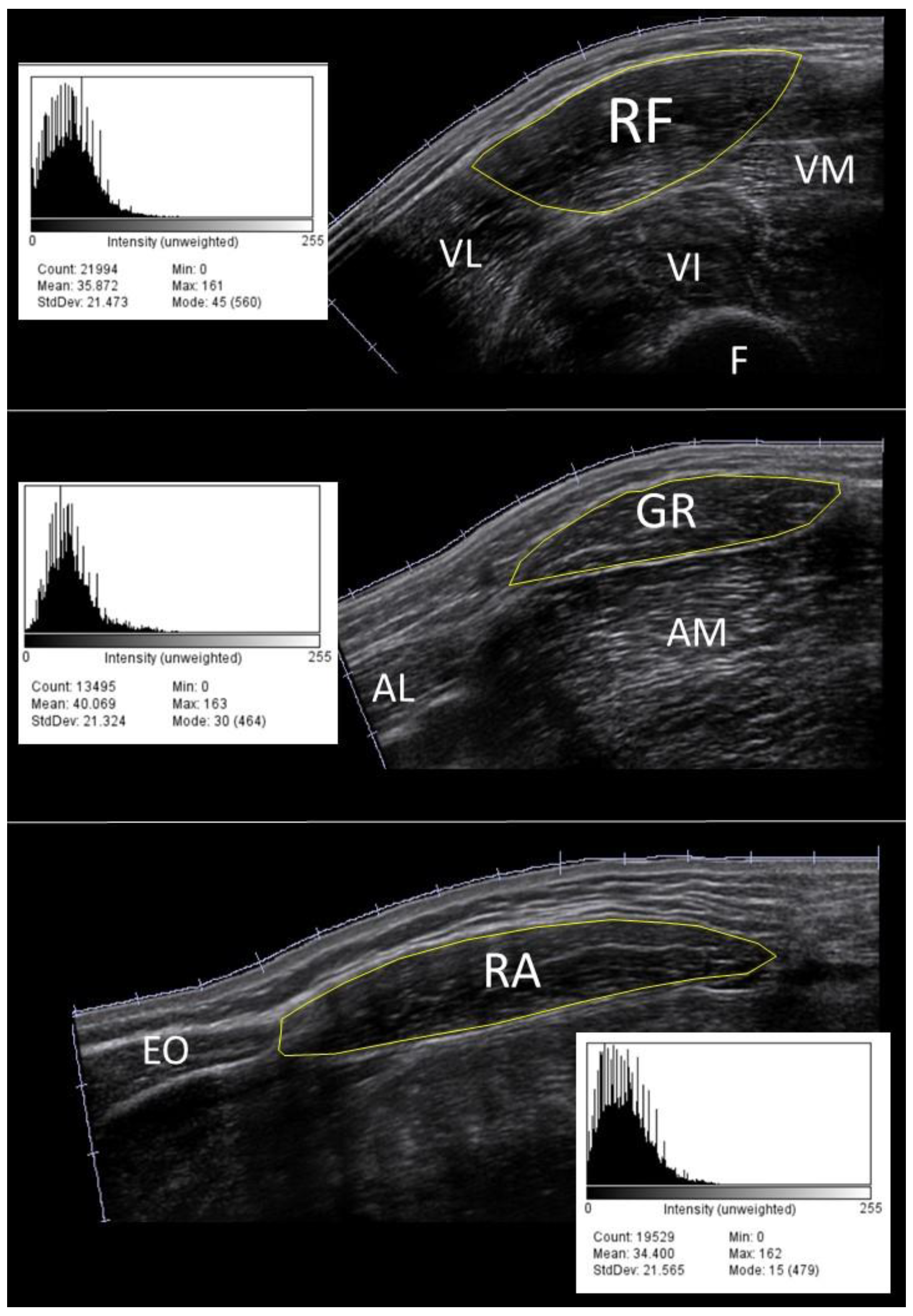

All acquired images were stored on a USB drive and imported to another computer for post-processing analysis. Before data extraction, through a first visual check, a dozen images were discarded and scanned again due to the presence of artifacts, caused by generic software issues. The cross-sectional area of the muscle was manually traced in each image using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). A region containing as much of the muscle as possible, avoiding intermuscular fascia and surrounding tissues was selected [

28]. The EI value of the cross-sectional area was computed based on the histogram of the image (8-bit resolution, resulting in an arbitrary unit (AU) between 0 and 256, where black=0 and white=255,

Figure 1).

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistic 29.0.1 software and the stand-alone mrcorrShiny App (

https://lmarusich.shinyapps.io/shiny_rmcorr/). Normality of data was examined with a Shapiro-Wilk test. Repeated measures correlations between a given parameter and EI values were calculated [

29]. A repeated measures ANOVA was performed to evaluate the differences between EI values across the settings of a given parameter. Mauchly’s test was used to assess the assumption of sphericity. In case ANOVA was significant, a post-hoc pairwise comparison with a Bonferroni adjustment was executed. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests.

Sample size calculation was based on the preliminary results of 11 participants in our study using the free software program G*Power© version 3.1.9.4 [

30]. The effect size was calculated directly using the partial eta squared (η

2p). For an effect size of 0.3, an alpha of 0.05, with a power of 80% and a correlation of 0.4 between the repeated measures, the sample size was estimated to be at least 20 participants.

3. Results

The characteristics of the 21 healthy participants were as follows: mean age (34.5 ± 8.7 years), height (174.9 ± 7.7 cm) and weight (72.8 ± 13.0 kg). The Shapiro-Wilk test showed normality for all EI measurements among all parameters (p>0.05). The results of the repeated measures analyses are summarized in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

3.1. Rectus Femoris Muscle

Dynamic range and EI were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(83) = -0.66, 95% CI [-0.77, -0.52], p < 0.001). Mean EI values differed significantly across DR (F(1.7,100) = 22.5, p<0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparison showed that mean EI values obtained using the default setup (at DR65) were significantly lower compared to mean EI values at DR30 (-8.0, 95%CI [-13.0, -3.0], p<0.001), and higher compared to values at DR125 (4.4, 95%CI [0.7, 8.0], p=0.013), and at DR150 (5.9, 95%CI [0.8, 11.0], p=0.016). Gray map and EI were significantly and positively correlated (rrm(62) = 0.45, 95%CI [0.23, 0.63], p<0.001). Mean EI values differed significantly across GM (F(3,80) = 17.5, p<0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons also showed that the mean default setup EI values were significantly lower compared to GM4 (-9.3, 95%CI [-14.1, -4.4], p<0.001), and GM8 (-10.3, 95%CI [-14.7, -5.8], p<0.001) EI values respectively. Persistence and EI were significantly and positively correlated (rrm(62) = 0.27, 95% CI [0.03, 0.49], p = 0.03). IClear and EI values were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(41) = -0.79, 95%CI [-0.64, -0.88], p<0.001). Mean EI values differed significantly across IC (F(1.4,60) = 34.0, p<0.001). The default EI values were significantly higher compared to IC2 (4.9, 95%CI [(1.9, 7.9], p=0.001) and IC4 (8.7, 95%CI [(5.4, 12.0], p<0.001).

Table 2.

Multiple comparison results for rectus femoris muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

Table 2.

Multiple comparison results for rectus femoris muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

| |

|

Repeated Measures |

| |

Echo Intensity |

Correlation |

Within-Subjects Effects |

Pairwise Comparisons |

| Parameter |

Mean ± SD |

rrm (95% CI) |

p |

df |

F |

p |

Mdiff (95% CI) |

p* |

| Default Setup$

|

DR 65

GM 2

LD M

PERS 0

IC 0 |

55.3 ± 14.6 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Modified settings |

| DR 30 |

63.3 ± 19.7 |

-0.66 (-0.52, -0.77) |

<0.001 |

1.7 |

22.5 |

<0.001 |

-8.0 (-13.0, -3.0) |

<0.001 |

| DR 90 |

51.1 ± 11.3 |

4.2 (-0.3, 8.7) |

0.086 |

| DR 125 |

50.9 ± 10.5 |

4.4 (0.7, 8.0) |

0.013 |

| DR 150 |

49.3 ± 8.9 |

5.9 (0.8, 11.0) |

0.016 |

| GM 4 |

64.5 ± 19.3 |

0.45 (0.23, 0.63) |

<0.001 |

3 |

17.5 |

<0.001 |

-9.3 (-14.1, -4.4) |

<0.001 |

| GM 6 |

58.7 ± 19.5 |

-3.4 (-8.3, 1.4) |

0.292 |

| GM 8 |

65.6 ± 16.4 |

-10.3 (-14.7, -5.8) |

<0.001 |

| LD L |

55.7 ± 15.6 |

0.05 (-0.20, 0.29) |

0.701 |

2.4 |

0.3 |

0.787 |

-0.4 (-4.3, 3.4) |

1.000 |

| LD H |

56.3 ± 15.5 |

-1.0 (-4.5, 2.4) |

1.000 |

| LD UH |

55.8 ± 14.6 |

-0.5 (-4.8, 3.8) |

1.000 |

| PERS 2 |

55.5 ± 14.3 |

0.27 (0.03, 0.49) |

0.030 |

2 |

1.4 |

0.261 |

-1.0 (-3.8, 1.8) |

1.000 |

| PERS 4 |

55.8 ± 15.5 |

-1.3 (-4.7, 2.1) |

1.000 |

| PERS 6 |

56.4 ± 15.6 |

-1.9 (-5.5, 1.6) |

0.775 |

| IC 2 |

50.4 ± 14.9 |

-0.79 (-0.64, -0.88) |

<0.001 |

1.4 |

34.0 |

<0.001 |

4.9 (1.9, 7.9) |

0.001 |

| IC 4 |

46.6 ± 15.0 |

8.7 (5.4, 12.0) |

<0.001 |

3.2. Gracilis Muscle

Dynamic range and EI were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(39) = -0.43, 95% CI [-0.14, -0.65], p=0.005). Mean EI values differed significantly across DR (F(4,45) = 4.9, p=0.003). Gray map and EI were significantly and positively correlated (rrm(29) = 0.43, 95% CI [0.09, 0.68], p=0.015). Mean EI values differed significantly across GM (F(3,36) = 15.4, p<0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons also showed that the mean default setup EI values were significantly lower compared to GM8 (-10.2, 95%CI [-17.8, -2.6], p=0.009) EI values. Line density and EI were significantly and positively correlated (rrm(29) = 0.52, 95% CI [0.20, 0.74], p=0.003). Mean EI values differed significantly across LD (F(3,36) = 3.7, p=0.024). IClear and EI were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(19) = -0.86, 95% CI [-0.68, -0.94], p<0.001). Mean EI values differed significantly across IC (F(2,27) = 31.4, p<0.001). The default EI values were significantly higher compared to IC2 (7.5, 95%CI [(3.1, 11.9], p=0.002) and IC4 (10.8, 95%CI [(6.5, 15.1], p<0.001).

Table 3.

Multiple comparison results for gracilis muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

Table 3.

Multiple comparison results for gracilis muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

| |

|

Repeated Measures |

| |

Echo Intensity |

Correlation |

Within-Subjects Effects |

Pairwise Comparisons |

| Parameter |

Mean ± SD |

rrm (95% CI) |

p |

df |

F |

p |

Mdiff (95% CI) |

p* |

| Default Setup$ |

DR 65

GM 2

LD M

PERS 0

IC 0 |

45.2 ± 10.2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Modified settings |

| DR 30 |

48.8 ± 12.3 |

-0.43 (-0.14, -0.65) |

0.005 |

4 |

4.9 |

0.003 |

-3.6 (-11.0, 3.9) |

1.000 |

| DR 90 |

41.3 ± 7.2 |

3.9 (-1.6, 9.4) |

0.291 |

| DR 125 |

43.0 ± 7.4 |

2.2 (-3.9, 8.3) |

1.000 |

| DR 150 |

43.5 ± 6.0 |

1.7 (-5.0, 8.4) |

1.000 |

| GM 4 |

50.9 ± 14.1 |

0.43 (0.09, 0.68) |

0.015 |

3 |

15.4 |

<0.001 |

-5.7 (-14.1, 2.6) |

0.276 |

| GM 6 |

43.5 ± 12.3 |

1.7 (-5.0, 8.4) |

1.000 |

| GM 8 |

55.3 ± 12.0 |

-10.2 (-17.8, -2.6) |

0.009 |

| LD L |

43.3 ± 10.6 |

0.52 (0.20, 0.74) |

0.003 |

3 |

3.7 |

0.024 |

1.8 (-2.7, 6.4) |

1.000 |

| LD H |

45.3 ± 11.1 |

-0.1 (-4.1, 3.9) |

1.000 |

| LD UH |

47.2 ± 11.2 |

-2.0 (-7.0, 2.9) |

1.000 |

| PERS 2 |

46.2 ± 10.2 |

0.02 (-0.33, 0.38) |

0.897 |

3 |

0.2 |

0.896 |

-1.0 (-5.6, 3.6) |

1.000 |

| PERS 4 |

45.2 ± 10.9 |

-0.01 (-7.1, 7.1) |

1.000 |

| PERS 6 |

45.7 ± 9.7 |

-0.6 (-6.4, 5.3) |

1.000 |

| IC 2 |

37.7 ± 10.9 |

-0.86 (-0.68, -0.94) |

<0.001 |

2 |

31.4 |

<0.001 |

7.5 (3.1, 11.9) |

0.002 |

| IC 4 |

34.4 ± 9.4 |

10.8 (6.5, 15.1) |

<0.001 |

3.3. Rectus Abdominis Muscle

Dynamic range and EI values were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(71) = -0.44, 95% CI [-0.61, -0.23], p<0.001). Echo intensity values differed significantly across DR (F(1.5,85) = 6.2, p=0.012). Gray map and EI were significantly and positively correlated (rrm(51) = 0.38, 95% CI [0.12, 0.59], p=0.006). Echo intensity values differed significantly across GM (F(1.9,60) = 7.9, p=0.002). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that mean EI values of the default setting were significantly lower compared to GM4 (-8.3, 95%CI [(-15.4, -1.1], p=0.019) and GM8 (-9.9, 95%CI [(-15.4, -4.5], p<0.001). IClear and EI values were significantly and inversely correlated (rrm(35) = -0.60, 95% CI [-0.35, -0.78], p < 0.001). Echo intensity values differed significantly across IC (F(1.3,51) = 9.8, p=0.002). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that mean EI values of the default setting were significantly higher compared to IC4 (7.6, 95%CI [(1.7, 13.5], p=0.002).

Table 4.

Multiple comparison results for rectus abdominis muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

Table 4.

Multiple comparison results for rectus abdominis muscle echo intensity values across settings in 21 healthy participants.

| |

|

Repeated Measures |

| |

Echo Intensity |

Correlation |

Within-Subjects Effects |

Pairwise Comparisons |

| Parameter |

Mean ± SD |

rrm (95% CI) |

p |

df |

F |

p |

Mdiff (95% CI) |

p* |

| Default Setup$ |

DR 65

GM 2

LD M

PERS 0

IC 0 |

46.2 ± 16.2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Modified settings |

| DR 30 |

51.1 ± 23.6 |

-0.44 (-0.23, -0.61) |

<0.001 |

1.5 |

6.2 |

0.012 |

-4.9 (-12.§, 2.8) |

0.557 |

| DR 90 |

43.1 ± 15.5 |

3.1 (-0.3, 6.4) |

0.086 |

| DR 125 |

43.8 ± 12.4 |

2.4 (-1.8, 6.5) |

0.815 |

| DR 150 |

43.3 ± 11.8 |

2.9 (-1.4, 7.2) |

0.448 |

| GM 4 |

53.6 ± 22.7 |

0.38 (0.12, 0.59) |

0.006 |

1.9 |

7.9 |

0.002 |

-8.3 (-15.4, -1.1) |

0.019 |

| GM 6 |

49.4 ± 23.7 |

-4.1 (-12.1, 4.0) |

0.859 |

| GM 8 |

55.3 ± 18.1 |

-9.9 (-15.4, -4.5) |

<0.001 |

| LD L |

45.2 ± 17.6 |

0.21 (-0.05, 0.45) |

0.116 |

2.6 |

0.8 |

0.467 |

1.0 (-4.9, 6.9) |

1.000 |

| LD H |

46.7 ± 17.9 |

-0.5 (-6.5, 5.4) |

1.000 |

| LD UH |

47.9 ± 19.9 |

-1.! (-7.5, 4.0) |

1.000 |

| PERS 2 |

48.6 ± 20.5 |

0.08 (-0.19, 0.34) |

0.571 |

3 |

1.0 |

0.405 |

-2.4 (-7.6, 2.8) |

1.000 |

| PERS 4 |

48.5 ± 19.7 |

-2.3 (-8.5, 3.9) |

1.000 |

| PERS 6 |

47.2 ± 18.1 |

-1.0 (-5.0, 3.0) |

1.000 |

| IC 2 |

42.8 ± 18.8 |

-0.60 (-0.35, -0.78) |

<0.001 |

1.3 |

9.8 |

0.002 |

3.4 (-1.0, 7.7) |

0.169 |

| IC 4 |

38.6 ± 18.5 |

7.6 (1.7, 13.5) |

0.009 |

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to better understand the influence of US parameter settings on EI values. According to current literature, this is the first study that looked at the effects of changing US parameter settings on EI other than gain and depth [

20,

21]. Our results show that changing B-mode ultrasound settings for image optimization may influence muscle EI outcome.

Manually adjusting the DR, GM and IC settings of an EFOV scan may change the EI value of skeletal muscle. We found weak to moderate negative correlations between DR and EI values in all three muscles examined. The correlation was stronger for the rectus femoris compared to the gracilis and rectus abdominis muscles. This may be explained by the fact that the mean differences in EI values across DR were larger in the rectus femoris (14.0 AU) compared to the gracilis (5.3 AU) and rectus abdominis (7.8 AU). This suggests that the influence of DR on EI might be muscle-dependent, as differences in EI may be more pronounced in muscles that have a higher variability in echo patterns. This is in agreement with previous results that reported that at least rectus femoris seems to be influenced by non-disease related factors, such as US parameters [

31,

32]. Although, according to present literature, there are no comparative US studies that examined the density of both muscles, previous CT-based studies showed intermuscular attenuation variations in both thigh and trunk muscles as a result of differences in fat accumulation [

33,

34]. For the aforementioned reasons, we suggest fixing DR at the midrange for the assessment of muscle quality at the potential expense of image quality in order to increase comparability of EI values between studies. Of the other US parameters, GM showed weak positive correlations with EI in all three muscles. Given this is the first report to assess the effect of changing the settings of these parameters, it is difficult to make well-established inferences on EI values. Gray map follows an S-shape pattern rather than a linear one in relation to EI values [

14]. This is in accordance with our findings in all three muscles, as increasing GM positively increased the EI value, with higher GM setting values (GM 4-GM 8) being similar to each other. Since the mean difference in EI value with the default setting exceeded the MDC95 of 10, it is suggested for comparability reasons to use a GM setting corresponding to the plateau phase of the S-curve. IClear setting values were strongly and negatively correlated with EI values. Although the mean differences with the default setting exceeded the MDC95 only in gracilis muscle, it is advisable to use a midrange setting for IC when using a muscle cross-section for the determination of EI values.

The lack of standard evaluation criteria currently represent the main limitation of US in the assessment of skeletal muscle quality [

35]. Our EI values obtained using the default setting of DR65 were substantially higher than those reported by Arts et al. [

16] but comparable to the ones reported by Yamada et al. [

17]. Although it might be speculative to attribute differences or similarities in EI values amongst studies solely to the effect of known US parameter settings, it is noticeable that both gain and DR were higher in the Arts study compared to Yamada’s and our settings. As there are no clear criteria for muscle EI value, results obtained by different US devices and settings are not comparable. As a result, the reference values that have been published until now are only usable in the clinical setting provided that the same US device with exactly the same US parameters settings are replicated [

35]. Therefore, given the challenges that remain in the assessment of muscle quality for diagnosing muscle disorders [

36], it is premature to establish universal reference values for specific populations. Moreover, despite the associations that have been found between EI values and functional outcomes, no attempts have been made to determine the minimally clinically important difference in muscle quality. As a result, the changes in health conditions routinely evaluated in clinical practice corresponding to EI values remain to be determined.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is the use of a whole cross-section analysis of muscles instead of a region of interest (ROI) based method. The whole cross-section approach is preferred, as it has been shown that the size and location of an ROI affect the repeatability and reproducibility in quantitative imaging [

37]. It is conceivable that by considering a larger area of muscle, the measurement error related to regional intra- and extramuscular differences in muscle composition [

38,

39,

40], as quantified by ROI placement, is reduced since muscle contours are traced manually using the ImageJ software.

Our laboratory has recently determined the reproducibility of EI measurements by comparing the test-retest estimates for skeletal muscles obtained in 31 subjects [

27]. The standard errors of measurement for the EI values of the rectus abdominis and rectus femoris muscles were 2.9 and 3.8 respectively. The minimally detectable changes at the 95% confidence level varied between 8.0 and 10.5 for the rectus abdominis and rectus femoris muscles respectively. Therefore, differences in EI smaller than the threshold of 10 AU may simply result from measurement error rather than differences in parameter settings.

A limitation of this study is the choice of muscles and the dynamic tracking location. We only studied rectus femoris, gracilis and rectus abdominis muscles at specific body sites. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to other muscles nor to other standardized locations of rectus femoris, gracilis or rectus abdominis muscle measurement. For example, it has been shown that rectus femoris muscle EI values differ significantly according to the location of measurement along the muscle belly [

39]. However, we cannot exclude that similar findings may be encountered in other skeletal muscles frequently affected by ectopic fat accumulation, especially in pathognomonic populations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we showed that EI values are significantly related to US parameters in healthy middle-aged subjects. We showed that EI values differ across the DR, GM and IC range in lower limb and trunk muscles. We therefore suggest using US parameter settings within their midrange in order to minimize the effect of setting-dependent factors on EI values. These findings reconfirm the need for standardization of ultrasound echo intensity settings when applied for diagnostic purposes of muscle quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., J.V.d.B. and P.B.; methodology, A.S., J.V.d.B. and P.B.; validation, J.V.d.B..; formal analysis, A.S. and M.C.G.; investigation, A.S., J.V.d.B. and P.B.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., J.V.d.B., P.B., E.C., H.J.-W., M.C.G.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, J.V.d.B.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL BRUSSELS (protocol code B.U.N. 1432020000335 on February 3th 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All raw data are available upon request at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was part of the doctoral thesis of the second author approved by the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Global nutrition policy review 2016-2017: country progress in creating enabling policy environments for promoting healthy diets and nutrition. Geneva, 2018; pp. 156.

- Walston, J.D. Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2012, 24, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; Schneider, S.M.; Sieber, C.C.; Topinkova, E.; Vandewoude, M.; Visser, M.; Zamboni, M. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.S.; Thompson, B.J. Echo intensity as an indicator of skeletal muscle quality: applications, methodology, and future directions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagae, M.; Umegaki, H.; Yoshiko, A.; Fujita, K. Muscle ultrasound and its application to point-of-care ultrasonography: a narrative review. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Kim, M. Meta-Analysis on the Association Between Echo Intensity, Muscle Strength, and Physical Function in Older Individuals. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2023; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T.; Nakamura, M.; Fukumoto, Y. Usefulness of muscle echo intensity for evaluating functional performance in the older population: A scoping review. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 182, 112301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunout, D.; Gonzalez, S.; Canales, M.; Barrera, G.; Hirsch, S. Ultrasound assessment of rectus femoris pennation angle and echogenicity. Their association with muscle functional measures and fat infiltration measured by CT scan. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 55, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, M.; van Alfen, N.; Nijhuis van der Sanden, M.W.G.; van Dijk, J.P.; Pillen, S.; de Groot, I.J.M. Quantitative muscle ultrasound is a promising longitudinal follow-up tool in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2012, 22, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidman, C.M.; Wu, J.S.; Kapur, K.; Pasternak, A.; Madabusi, L.; Yim, S. Quantitative muscle ultrasound detects disease progression in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillen, S.; Arts, I.M.P.; Zwarts, M.J. Muscle ultrasound in neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve 2008, 37, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillen, S.; van Keimpema, M.; Nievelstein, R.A.J.; Verrips, A.; van Kruijsbergen-Raijmann, W.; Zwarts, M.J. Skeletal muscle ultrasonography: Visual versus quantitative evaluation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006, 32, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Alfen, N.; Gijsbertse, K.; de Korte, C.L. How useful is muscle ultrasound in the diagnostic workup of neuromuscular diseases? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, D.; Hüske, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Cui, X.W.; Dong, Y.; Lim, A.; Jenssen, C.; Löwe, A.; Koch, J.B.H.; Dietrich, C.F. Ultrasound image optimization (“knobology”): B-mode. Ultrasound Int. Open 2020, 6, E14–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkisas, S.; Bastijns, S.; Baudry, S.; Bauer, J.; Beaudart, C.; Beckwée, D.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Gasowski, J.; Hobbelen, H.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Kasiukiewicz, A.; Landi, F.; Małek, M.; Marco, E.; Martone, A.M.; de Miguel, A.M.; Piotrowicz, K.; Sanchez, E.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, D.; Scafoglieri, A.; Vandewoude, M.; Verhoeven, V.; Wojszel, Z.B.; De Cock, A.M. Application of ultrasound for muscle assessment in sarcopenia: 2020 SARCUS update. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, I.M.; Pillen, S.; Schelhaas, H.J.; Overeem, S.; Zwarts, M.J. Normal values for quantitative muscle ultrasonography in adults. Muscle Nerve 2010, 41, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Kimura, Y.; Ishiyama, D.; Nishio, N.; Abe, Y.; Kakehi, T.; Fujimoto, J.; Tanaka, T.; Ohji, S.; Otobe, Y.; Koyama, S.; Okajima, Y.; Arai, H. Differential characteristics of skeletal muscle in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 807.e9–807.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurits, N.M.; Bollen, A.E.; Windhausen, A.; De Jager, A.E.; Van Der Hoeven, J.H. Muscle ultra-sound analysis: Normal values and differentiation between myopathies and neuropathies. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2003, 29, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidman, C.M.; Holland, M.R.; Anderson, C.C.; Pestronk, A. Calibrated quantitative ultrasound imaging of skeletal muscle using backscatter analysis. Muscle Nerve 2008, 38, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffel, C.N.; Brown, R.; Korcarz, C.E.; Varghese, T.; Stein, J.H.; Wilbrand, S.M.; Dempsey, R.J.; Mitchell, C.C. Influence of ultrasound system and gain on grayscale median values. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018, 38, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M.T.; Bell, K.E.; Avrutin, E.; Mourtzakis, M. Ultrasound image resolution influences analysis of skeletal muscle composition. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2020, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ata, A.M.; Kara, M.; Kaymak, B.; Gürçay, E.; Çakır, B.; Ünlü, H.; Akıncı, A.; Özçakar, L. Regional and total muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance: The potential use of ultrasound imaging for sarcopenia. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, C.J.; Kuipers, R.; Rombouts, J.A.; Brouwers, K.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; Wildberger, J.E.; Verdijk, L.B. , van Loon, L.J.C. Thigh muscles are more susceptible to age-related muscle loss when compared to lower leg and pelvic muscles. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 175, 112159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomaes, T.; Thomis, M.; Onkelinx, S.; Coudyzer, W.; Cornelissen, V.; Vanhees, L. Reliability and validity of the ultrasound technique to measure the rectus femoris muscle diameter in older cad-patients. BMC Med. Imaging 2012, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.P.; Penn, K.; Kaplan, S.J.; Vrablik, M.; Jablonowski, K.; Pham, T.N.; Reed, M.J. Comparison of bedside screening methods for frailty assessment in older adult trauma patients in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, N.I.; Ogawa, M.; Yoshiko, A.; Ando, R.; Akima, H. Reliability of size and echo intensity of abdominal skeletal muscles using extended field-of-view ultrasound imaging. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 17, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broeck, J.; Héréus, S.; Cattrysse, E.; Raeymaekers, H.; De Maeseneer, M.; Scafoglieri, A. Reliability of Muscle Quantity and Quality Measured With Extended-Field-of-View Ultrasound at Nine Body Sites. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2023, 49, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijntjes, J.; van Alfen, N. Muscle ultrasound: Present state and future opportunities. Muscle Nerve. 2021, 63, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakdash, J.Z.; Marusich, L.R. Repeated Measures Correlation. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Meth. 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Payá, J.J.; Del Baño-Aledo, M.E.; Ríos-Díaz, J.; Tembl-Ferrairó, J.I.; Vázquez-Costa, J.F.; Medina-Mirapeix, F. Muscular echovariation: A new biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Payá, J.J.; Ríos-Díaz, J.; Del Baño-Aledo, M.E.; Tembl-Ferrairó, J.I.; Vazquez-Costa, J.F.; Medina-Mirapeix, F. Quantitative muscle ultrasonography using textural analysis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ultrason. Imaging 2017, 39, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.E.; D’Agostino, J.M.; Bruno, A.G.; Demissie, S.; Kiel, D.P.; Bouxsein, M.L. Variations of CT-Based Trunk Muscle Attenuation by Age, Sex, and Specific Muscle. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P.; Marques, E.A.; Gudnason, V.; Lang, T.; Sigurdsson, S.; Jonsson, P.V.; Aspelund, T.; Siggeirsdottir, K.; Launer, L.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Harris, T.B. Computed tomography-based skeletal muscle and adipose tissue attenuation: Variations by age, sex, and muscle. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 149, 111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti, A.; De Cinque, A.; Fazio, N.; Napoli, A.; Guglielmi, G.; Bazzocchi, A. Ultrasound imaging, a stethoscope for body composition assessment. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2020, 10, 1699–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidman, C.M.; Holland, M.R.; Hughes, M.S. Quantitative ultrasound of skeletal muscle: Reliable measurements of calibrated muscle backscatter from different ultrasound systems. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012, 38, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, A.; Fujita, S.; Ohno, Y.; Aoki, S. Variability and standardization of quantitative imaging: monoparametric to multiparametric quantification, radiomics, and artificial intelligence. Invest. Radiol. 2020, 55, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, K.; Reimers, C.D.; Wagner, S.; Paetzke, I.; Pongratz, D.E. Skeletal muscle sonography: A correlative study of echogenicity and morphology. J. Ultrasound Med. 1993, 12, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caresio, C.; Molinari, F.; Emanuel, G.; Minetto, M.A. Muscle echo intensity: Reliability and conditioning factors. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2014, 35, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozier, C.; Keen, M.; Collins, K.; Tolzman, J.; Fajardo, R.; Slade, J.M.; Kuenze, C.; Harkey, M.S. Rectus Femoris Ultrasound Echo Intensity Is a Valid Estimate of Percent Intramuscular Fat in Patients Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2023, 49, 2590–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).