Submitted:

30 January 2024

Posted:

31 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

Survey instrument

Ethical considerations

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

LIMITS

CONCLUSIONS

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Declarations of interest

Disclosure

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amuta, A.O.; Mkuu, R.S.; Jacobs, W.; Ejembi, A.Z. Influence of Cancer Worry on Four Cancer Related Health Protective Behaviors among a Nationally Representative Sample: Implications for Health Promotion Efforts. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, C.; Abate, D.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdel-Rahman, O.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdoli, A.; Abdollahpour, I.; Abdulle, A.S.M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. The Global Cancer Observatory 2020 China Fact Sheets. Https://Gco.Iarc.Fr/Today/Data/ Factsheets/Populations/160-China-Fact-Sheets.Pdf. Published; 2021.

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today. (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Fan, L.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, K.-D.; Liu, G.-Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.-S.; Shen, K.-W.; Shen, Z.-Z.; Shao, Z.-M. Breast Cancer in a Transitional Society over 18 Years: Trends and Present Status in Shanghai, China. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 117, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Xiao, Y.; Mo, M.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Shao, Z.-M. Breast Cancer Screening and Early Diagnosis in Chinese Women. Cancer Biol. Med. 2022, 19, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIOM-AIRTUM-Siapec-Iap I Numeri Del Cancro in Italia 2022. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2022_AIOM_NDC-web.pdf. (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Petrelli, A.; Di Napoli, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Rossi, A.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Demuru, E.; Costa, G.; Zengarini, N.; Alicandro, G.; Marchetti, S.; et al. Italian Atlas of Mortality Inequalities by Education Level. Epidemiol. Prev. 2019, 43, 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, A.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Francovich, L.; Giordani, B.; Di Napoli, A.; Zappa, M.; Mirisola, C.; Gargiulo, L. Geographical and Socioeconomic Differences in Uptake of Pap Test and Mammography in Italy: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegwarth, O.; Widschwendter, M.; Cibula, D.; Sundström, K.; Portuesi, R.; Lein, I.; Rebitschek, F.G. What Do European Women Know about Their Female Cancer Risks and Cancer Screening? A Cross-Sectional Online Intervention Survey in Five European Countries. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliassen, A.H.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.C.; Hankinson, S.E. Adult Weight Change and Risk of Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. JAMA 2006, 296, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulka, B.S.; Moorman, P.G. Breast Cancer: Hormones and Other Risk Factors. Maturitas 2001, 38, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, H.B.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Egan, K.M.; Titus-Ernstoff, L.; Holmes, M.D.; Bersch, A.J.; Holick, C.N.; Hampton, J.M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; et al. Body Mass Index Before and After Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Associations with All-Cause, Breast Cancer, and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Sharma, D. Microbial Alterations and Risk Factors of Breast Cancer: Connections and Mechanistic Insights. Cells 2020, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.; Whitehead, S.A. Phytoestrogens and Breast Cancer –Promoters or Protectors? Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.C. Diet and Cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C. Diet and Cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholc, M.; Łepecka-Klusek, C.; Pilewska, A.; Kanadys, K. Ryzyko Zachorowania Na Raka Piersi w Opinii Kobiet. Ginekol Pol 2001, 72, 1460–1456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Ko, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lim, J.-E. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and the Risk of Breast Cancer by Histological Type and Race: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Cohort Studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 170, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuzak, T.Z.; Hałgas, M.; Kowalska, K.; Gospodarczyk, M.; Wdowiak-Filip, A.; Filip, M.; Zuzak, Z.; Kowaluk, G.; Wdowiak, A. Breast Cancer – the Level of Knowledge about Epidemiology and Prophylaxis among Polish Medical Universities Students. Eur. J. Med. Technol. 2018, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, M.M.; Knowles, M.H.; Robison, R.A.; O’Neill, K.L. Mechanics behind Breast Cancer Prevention - Focus on Obesity, Exercise and Dietary Fat. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 2207–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, M.; Ciszewski, T.; Łopacka-Szatan, K.; Miotła, P.; Starosławska, E. Breast Cancer Risk Factors. Menopausal Rev. 2015, 3, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, V.-F.; Baban, A.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Psychological Stress and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review. Clujul Med. 2018, 91, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.; Tseng, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Conroy, S.M.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Li, L.; Hertz, A.; Gomez, S.L.; Le Marchand, L.; et al. Association between Ambient Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, W.E. Performance of Diagnostic Mammography for Women With Signs or Symptoms of Breast Cancer. CancerSpectrum Knowl. Environ. 2002, 94, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, L.; De Nunzio, G.; Lupo, R.; Mieli, M.; Lezzi, A.; Vitale, E.; Carriero, M.C.; Calabrò, A.; Carvello, M.; Rubbi, I.; et al. Breast Cancer Prevention: The Key Role of Population Screening, Breast Self-Examination (BSE) and Technological Tools. Survey of Italian Women. J. Cancer Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirian, S.; Barati, M.; Mohammadi, Y.; MoaddabShoar, L.; Dogonchi, M. Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Promoting Breast Self-Examination Behavior in Employed Women in Iran. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2021, 15, 1178223421989657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Women. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1152, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministery of Health Screening Oncologici. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/donna/dettaglioContenutiDonna.jsp?id=4511&area=Salute+donna&menu=prevenzione (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- De Cicco, P.; Catani, M.V.; Gasperi, V.; Sibilano, M.; Quaglietta, M.; Savini, I. Nutrition and Breast Cancer: A Literature Review on Prevention, Treatment and Recurrence. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, R.A.; Sorkin, J.D.; Frey, C.M.; Kessler, L.G. Americans’ Knowledge of Cancer Risk and Survival. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 1997, 26, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, S.; Qin, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Du, J.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Y.; Han, Z.; Yu, Y.; et al. Diet, Sports, and Psychological Stress as Modulators of Breast Cancer Risk: Focus on OPRM1 Methylation. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 747964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, H.J.; Han, W. A Review of the Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Asia: Focus on Risk Factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reményi Kissné, D.; Gede, N.; Szakács, Z.; Kiss, I. Breast Cancer Screening Knowledge among Hungarian Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Womens. Health 2021, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.A.; Al-Marzouki, A.; Otim, M.; Khalil Khayat, N.E.H.; Yousuf, R.; Rahman, P. Awareness about Breast Cancer and Breast Self-Examination among Female Students at the University of Sharjah: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mousa, D.S.; Alakhras, M.; Hossain, S.Z.; Al-Sa’di, A.G.; Al Hasan, M.; Al-Hayek, Y.; Brennan, P.C. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Around Breast Cancer and Mammography Screening Among Jordanian Women. Breast cancer (Dove Med. Press. 2020, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renganathan, L.; Ramasubramaniam, S.; Al-Touby, S.; Seshan, V.; Al-Balushi, A.; Al-Amri, W.; Al-Nasseri, Y.; Al-Rawahi, Y. What Do Omani Women Know about Breast Cancer Symptoms? Oman Med. J. 2014, 29, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, S.; Okwuokei, S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Women towards Breast Cancer in Benin City, Nigeria. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, K.; Masiero, M.; Carriero, M.C.; Pravettoni, G. The Role of Emotions in Cancer Patients’ Decision-Making. Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

SECTION 1: SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS |

Group A: Individuals from the general population (98%, n=1118) |

Group B: Patients with breast cancer (2%, n=26) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 20-29 | 263 (24) | 2 (8) | <0.001*** |

| 30-39 | 427 (38) | 5 (19) | |

| 40-49 | 211 (19) | 6 (23) | |

| 50-59 | 160 (14) | 8 (31) | |

| 60-69 | 57 (5) | 5 (19) | |

|

Geographical Area North Center South and Islands |

377 (34) 422 (38) 319 (29) |

18 (69) 6 (23) 2 (8) |

0.81 |

|

Marital Status Married Divorced Single Separated Widowed |

528 (47) 54 (5) 446 (40) 73 (7) 17 (2) |

9 (35) 9 (35) 3 (12) 1 (4) 4 (15) |

0.53 |

|

Educational level Degree High school graduation Junior High School Diploma Elementary Education None |

36 (3) 184 (16) 696 (62) 160 (14) 42 (4) |

3 (12) 3 (12) 14 (54) 3 (12) 3 (12) |

0.85 |

|

Occupational Status Worker Housewife Public Employee Freelancer Student Retired Other Unemployed |

310 (28) 194 (17) 62 (6) 92 (8) 197 (18) 113 (10) 150 (13) 0 |

4 (15) 5 (19) 1 (4) 2 (8) 2 (8) 7 (27) 5 (19) 0 |

0.56 |

|

Are you currently working? No Yes |

466 (42) 652 (58) |

11 (42) 15 (58) |

0.94 |

|

Years in Italy Range Mean SD |

1-50 17.95 9.64 |

2-44 21.34 14.09 |

0.298 |

|

SECTION 2. ACCESS TO HEALTH SERVICES |

Group A: Individuals from the general population (98%, n=1118) |

Group B: Patients with breast cancer (2%, n=26) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you enrolled in the National Health Service (NHS)? |

2 (0) 1116 (100) |

0 26 (100) |

0.83 |

| No Yes | |||

|

Did you encounter any difficulties in enrollment? I don't have a residence permit I tried but had difficulty I don't know how to do it I never thought about it I don't care I had no difficulty |

43 (4) 17 (2) 33 (3) 20 (2) 16 (1) 989 (88) |

5 (19) 1 (4) 2 (8) 1 (4) 1 (4) 16 (62) |

<0.001*** |

|

During the past two years, have you relied on the services of your primary care physician? No Yes |

243 (22) 875 (78) |

8 (31) 18 (69) |

0.27 |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the Pediatrician? No Yes |

850 (76) 267 (24) |

8 (31) 18 (69) |

0.41 |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the Emergency Room (ER)? No Yes |

941 (84) 177 (16) |

18 (69) 8 (31) |

0.04* |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the Hospital? No Yes |

923 (83) 195 (17) |

18 (69) 8 (31) |

0.07 |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the Gynecological Consultatory? No Yes |

853 (76) 265 (24) |

19 (73) 7 (27) |

0.70 |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the CUP (Centralized Booking Center) Service? No Yes |

923 (83) 195 (17) |

20 (77) 6 (23) |

0.45 |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on the services of the Vaccine Outpatient Clinic? No Yes |

923 (83) 195 (17) |

8 (31) 18 (69) |

0.01* |

|

Over the past two years, have you relied on anything else? No Yes |

819 (73) 299 (27) |

13 (50) 13 (50) |

0.008** |

|

Have you chosen your primary care physician? No Yes |

74 (7) 1044 (93) |

7 (27) 19 (73) |

<0.001*** |

|

In the past year, how many times have you relied on your family physician? Never 1 time 2-5 times >5 times |

384 (34) 241 (22) 399 (36) 94 (8) |

4 (15) 11 (42) 9 (35) 2 (8) |

0.01* |

|

Are you comfortable with your family physician? Not at all Little I don't know. Quite Very |

40 (4) 628 (56) 64 (6) 343 (31) 43 (4) |

1 (4) 12 (46) 3 (12) 8 (31) 2 (8) |

0.28 |

|

What problems does it report about the family physician? Schedules don't fit I have difficulty understanding the recipes We don't understand each other because of the language I've never had any problems More |

291 (26) 36 (3) 83 (7) 29 (3) 679 (61) |

4 (15) 4 (15) 4 (15) 3 (12) 11 (42) |

0.006** |

|

In the past year, have you relied on the services of the CUP Service? No Yes |

853 (76) 265 (24) |

16 (62) 10 (38) |

0.08 |

|

What problems do you report on CUP? It is not clear how it works It was difficult to book I've never had any problems More |

83 (7) 138 (12) 74 (7) 823 (74) |

8 (31) 3 (12) 3 (12) 12 (46) |

0.005** |

|

In the past year, how many times have you relied on the emergency room? Never 1 time 2-5 times >5 times |

793 (71) 229 (20) 92 (8) 4 (0) |

2 (8) 12 (46) 12 (46) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

Were you satisfied with the service? Not at all Little I don't know. Quite A lot |

39 (3) 866 (77) 114 (10) 65 (6) 34 (3) |

3 (12) 14 (54) 2 (8) 4 (15) 3 (12) |

0.01* |

|

What problems do you report about the emergency room? The operators did not have time to explain We didn't understand each other because of the language It is unclear how access works Other |

68 (6) 87 (8) 51 (5) 912 (82) |

6 (23) 5 (19) 2 (8) 13 (50) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you know that there is a night and holiday medical service? No Yes |

105 (9) 1013 (91) |

8 (31) 18 (69) |

<0.001*** |

|

In case of need, would you know how to contact this medical service? No Yes |

335 (30) 783 (70) |

7 (27) 19 (73) |

0.73 |

|

Are you aware of the existence of the Counseling Center? No Yes |

845 (76) 273 (24) |

12 (46) 14 (54) |

<0.001*** |

|

Have you ever used the Counseling Center? No Yes |

985 (88) 133 (12) |

17 (65) 9 (35) |

<0.001*** |

|

If yes, for what reason? Psychological assistance PAP test Contraception Scheduled checks in pregnancy Termination of pregnancy Gynecological examination Other |

17 (2) 8 (1) 33 (3) 47 (4) 13 (1) 59 (5) 941 (84) |

1 (4) 0 2 (8) 5 (19) 2 (8) 4 (15) 12 (46) |

<0.001*** |

|

Were you satisfied with the service of the Counseling Center? Not at all Little I don't know. Quite A lot |

31 (3) 75 (7) 914 (82) 32 (6) 36 (3) |

3 (12) 1 (4) 13 (50) 6 (23) 3 (12) |

<0.001*** |

| Group A Women in the general population aged 50-69 (n=217) N (%) |

Group B Women with cancer aged 50-69 (n=13) N (%) |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

SECTION 3: Clinical breast cancer controls and adherence to screening programs, women aged 50-69 | |||

|

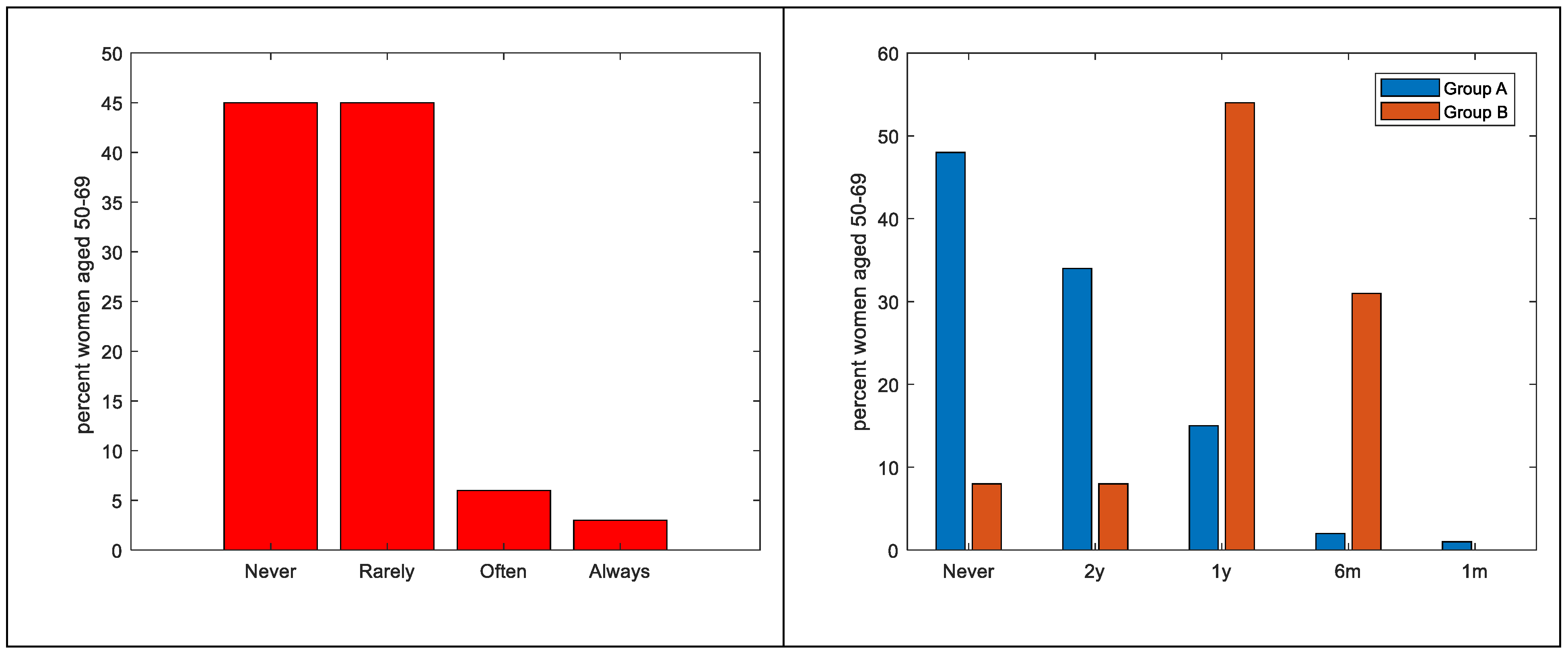

Have you ever done a clinical controls for early detection of breast cancer? Never Rarely Occasionally Often Always |

103 (47) 102 (47) 0 7 (3) 5 (2) |

1 (8) 2 (15) 0 7 (54) 2 (23) |

<0.001*** |

| If yes, please indicate the frequency | 0.47 | ||

| I have never had a screening exam | 104 (48) | 1 (8) | |

| Every 2 years | 74 (34) | 1 (8) | |

| Every year | 32 (15) | 7 (54) | |

| Every 6 months Every month |

4 (2) 3 (1) |

4 (31) 0 |

|

|

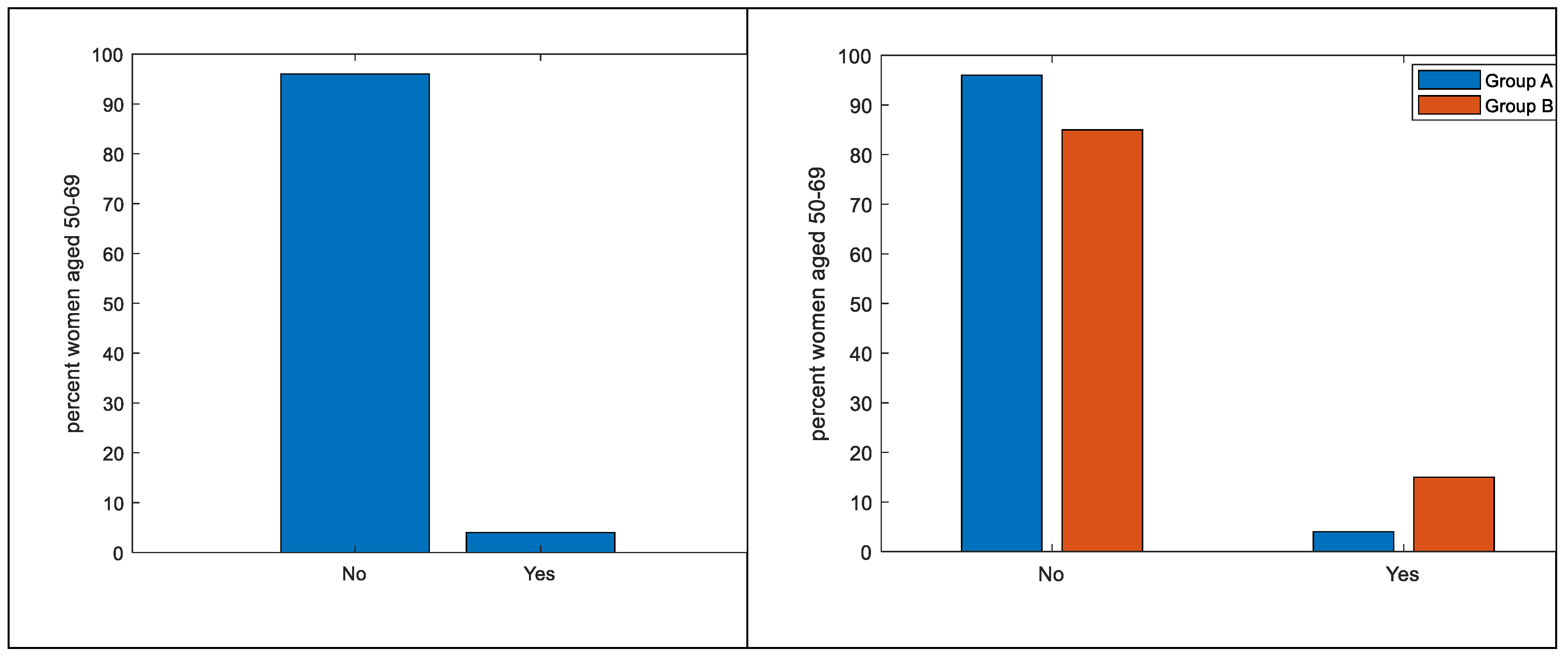

Have you ever taken advantage of the free screening offered by the region? No Yes I don't know them |

209 (96) 8 (4) 0 |

11 (85) 2 (15) 0 |

0.04* |

|

Have you ever been called by the LHA (Local Health Authority) for a visit dedicated to prevention? Yes, breast cancer (mammography) Yes, for colorectal cancer (stool analysis) Yes, for cervical cancer (PAP test) No, I did not receive the letter I don’t know |

3 (1) 4 (2) 0 157 (72) 53 (24) |

1 (8) 1 (8) 0 6 (46) 5 (38) |

0.73 |

|

If you received the letter, how understandable was it? Not at all Little I don't know Quite A lot |

8 (4) 40 (18) 151 (70) 0 18 (8) |

1 (8) 1 (8) 7 (54) 0 4 (31) |

0.50 |

|

Have you ever had a biopsy? No Yes Missing |

154 (71) 63 (29) 0 |

8 (62) 5 (38) 0 |

0.47 |

|

Have you ever had a mammogram? No Yes missing |

154 (71) 63 (29) 0 |

1 (8) 12 (92) 0 |

<0.01** |

|

Have you ever had an ultrasound? No Yes missing |

191 (88) 26 (12) 0 |

1 (8) 12 (92) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

Have you ever had a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)? No Yes Missing |

201 (93) 16 (7) 0 |

8 (62) 5 (38) 0 |

<0.001*** |

| Group A Women in the general population (n=1118) N (%) |

Group B Women with cancer (n=26) N (%) |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

SECTION 4: Approach to breast self- examination (BSE) | |||

|

Have you ever heard of BSE? No Yes |

98 (9) 1020 (91) |

9 (35) 17 (65) |

<0.001*** |

|

In your opinion, what does self-examination consist of? Breast self-examination Clinical examination of the breast (search for visible and/or palpable findings in the breast and surrounding areas, e.g., areas of lymphatic drainage axilla, neck) Radiological examination of the breast (mammography, ultrasonography, MRI, biopsy, chest X-ray, scintigraphy, CT scan, PET/CT, chest X-ray) I don't know Other |

51 (5) 284 (25) 717 (64) 50 (4) 16 (1) |

3 (12) 7 (27) 9 (35) 5 (19) 2 (8) |

<0.001*** |

|

Does self-examination help prevent breast cancer? No Yes |

80 (7) 1038 (93) |

6 (23) 20 (77) |

0.002** |

|

Is self-palpation not necessary if I perform periodic mammography? Strongly agree Agreed In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

52 (5) 194 (17) 144 (13) 5 (0) 723 (65) |

4 (15) 8 (31) 11 (42) 0 3 (12) |

<0.001*** |

|

Performing a self-examination reduces mortality. Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

78 (7) 590 (53) 6 (1) 1 (0) 443 (40) |

11 (42) 13 (50) 0 0 2 (8) |

0.18 |

|

Performing self-examination every month helps me find the nodules Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

34 (3) 104 (9) 105 (9) 7 (1) 868 (78) |

4 (15) 9 (35) 2 (8) 0 11 (42) |

<0.001*** |

|

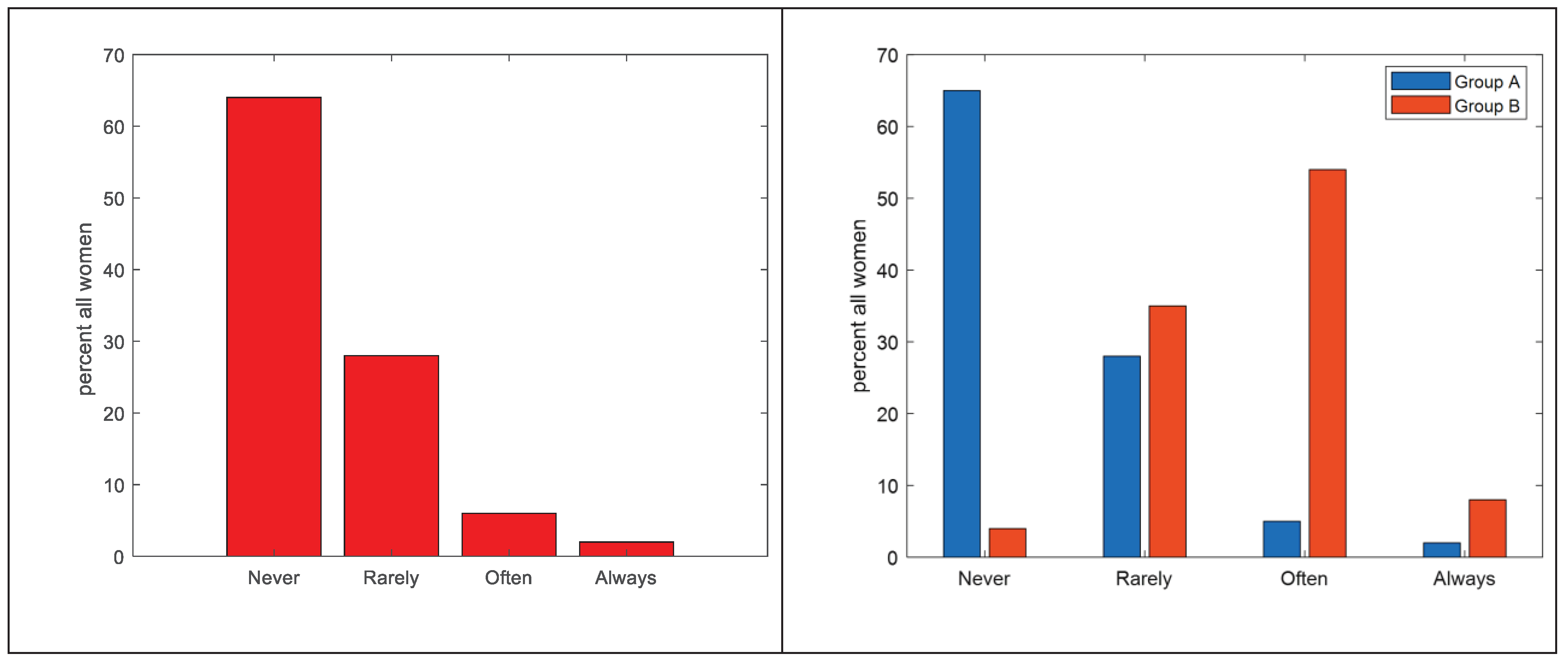

How often do you perform self palpation? Never Rarely Occasionally Often Always |

731 (65) 313 (28) 0 57 (5) 17 (2) |

1 (4) 9 (35) 0 14 (54) 2 (8) |

<0.001*** |

|

If not, state the reason I perform it I am not at risk I don't remember to run it Fear of ominous prognosis I don't know how to execute it properly I don't know what it is missing |

278 (25) 88 (8) 62 (6) 101 (9) 37 (3) 32 (3) 0 |

12 (46) 3 (12) 4 (15) 2 (8) 4 (15) 0 1 (4) |

<0.001*** |

|

When I do self-examination, I take care of myself. Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

75 (7) 997 (89) 32 (3) 11 (1) 3 (0) |

11 (42) 13 (50) 1 (4) 1 (4) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

Self-palpation is embarrassing Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

38 (3) 103 (9) 704 (63) 267 (24) 6 (1) |

5 (19) 8 (31) 1 (4) 12 (46) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

Self-examination takes too much time Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

52 (5) 120 (11) 715 (64) 230 (21) 1 (0) |

6 (23) 8 (31) 1 (4) 11 (42) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

I have more important problems than self-examination Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

48 (4) 90 (8) 877 (78) 101 (9) 2 (0) |

4 (15) 9 (35) 7 (27) 6 (23) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

I am able to perform self-examination correctly Strongly agree Agree In disagreement Strongly disagree Uncertain |

35 (3) 81 (7) 843 (75) 147 (13) 12 (1) |

3 (12) 8 (31) 13 (50) 2 (8) 0 |

<0.001*** |

|

I would like more information about self- examination. Yes No |

1013 (91) 105 (9) |

18 (68) 8 (31) |

<0.001*** |

|

Which figure do you find helpful in getting information about self-examination? Primary care physician Nurse Oncologist Psychologist Breast specialist Other |

27 (2) 17 (2) 271 (24) 777 (69) 14 (1) |

1 (4) 1 (4) 9 (35) 1 (4) 11 (42) 3 (12) |

0.001*** |

|

SECTION 5: KNOWLEDGE AND USE OF APPS DEDICATED TO PREVENTION | |||

|

Do you know or use dedicated applications for self-examination? No Yes |

1016 (91) 102 (9) |

18 (69) 8 (31) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you use BreastTest? No Yes |

1091 (98) 27 (2) |

25 (96) 1 (4) |

0.64 |

|

Do you use Igyno? No Yes |

1094 (98) 24 (2) |

26 (100) 0 |

0.45 |

|

Do you use Breast Cancer Indicators? No Yes |

1090 (97) 28 (3) |

26 (100) |

0.41 |

|

Do you use other apps? No Yes |

1090 (97) 28 (3) |

25 (96) 1 (4) |

0.66 |

| Group A Women in the general population (n=1118) N (%) |

Group B Women with cancer (n=26) N (%) |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

SECTION 6: Knowledge and beliefs about the causes and symptomatology of breast cancer | |||

|

Do you think you are well informed about breast cancer? A lot Little Quite Not at all |

26 (2) 80 (7) 939 (84) 73 (7) |

5 (19) 13 (50) 6 (23) 2 (8) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you think the cause of breast cancer is genetics? No Yes |

71(6) 1047 (94) |

5 (19) 21 (81) |

0.009** |

|

Do you think the cause of breast cancer is endocrine? No Yes |

155 (14) 963 (86) |

4 (15) 22 (85) |

0.82 |

|

Do you think a cause of breast cancer may be previous breast disease? No Yes |

320 (29) 798 (71) |

9 (35) 17 (65) |

0.50 |

|

Do you think one cause of breast cancer may be radiation? No Yes |

951 (85) 167 (15) |

18 (69) 8 (31) |

0.02* |

|

Do you think one cause of breast cancer may be nutrition? No Yes |

856 (77) 262 (23) |

9 (35) 17 (65) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you think a cause of breast cancer may be environmental factors and pollution? No Yes |

929 (83) 189 (17) |

14 (54) 12 (46) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you think a cause of breast cancer may be psychological stress? No Yes |

532 (48) 586 (52) |

5 (19) 21 (81) |

0.004** |

|

Do you think the cause of breast cancer may be another one? No Yes |

573 (51) 545 (49) |

10 (38) 16 (62) |

0.19 |

|

What do you think the symptoms of cancer might be? Palpable nodule Change in breast shape and size Nipple secretion Nipple alteration Other I don't know |

135 (12) 700 (63) 69 (6) 70 (6) 4 (0) 30 (3) |

6 (23) 14 (54) 2 (8) 3 (12) 0 1 (4) |

0.44 |

|

SECTION 7: Knowledge and beliefs about breast cancer prevention | |||

|

Do you feel that you are well informed about breast cancer prevention? A lot Quite Little Not at all |

22 (2) 69 (6) 955 (85) 72 (6) |

7 (27) 13 (50) 4 (15) 2 (8) |

<0.001*** |

|

What does prevention mean to you? Early detection of cancers Prevention of risk factors Prevention of complications Don't know More |

301 (27) 593 (53) 159 (14) 41 (4) 24 (2) |

11 (42) 5 (19) 2 (8) 6 (23) 2 (8) |

<0.001*** |

|

At what age do you think mammography is recommended? <20 years old 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70 I don't know |

6 (1) 41 (4) 118 (11) 199 (18) 569 (51) 165 (15) 20 (2) |

0 0 2 (8) 4 (15) 15 (58) 3 (12) 1 (8) |

0.26 |

|

How often do you think mammography is recommended? Basedon age/familiarity More than every year Every month Every 6 months Every year Every 2 years I don't know |

0 0 11 (1) 66 (6) 846 (76) 141 (13) 54 (5) |

0 0 0 2 (8) 13 (50) 5 (19) 6 (23) |

0.0057 |

|

Do you consider clinical palpation useful as an act of breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

117 (10) 1001 (90) |

4 (15) 22 (85) |

0.42 |

|

Do you think Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is useful for breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

501 (45) 617 (55) |

5 (19) 21 (81) |

0.009** |

|

Do you consider biopsy useful as an act of breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

928 (83) 190 (17) |

13 (50) 13 (50) |

<0.001*** |

|

Do you think computed tomography (CT) is useful for breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

639 (57) 479 (43) |

8 (31) 18 (69) |

0.007** |

|

Do you think blood tests are useful for breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

839 (75) 279 (25) |

13 (50) 13 (50) |

0.003** |

|

Do you find the interview with the oncologist useful as an act of breast cancer prevention? No Yes |

84 (8) 1034 (92) |

4 (15) 22 (85) |

0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).