1. Introduction

Tourism is mobile, and consumption typically occurs off-site. Consequently, the tourism industry reacts strongly to crisis events and is very sensitive to changes in the external environment (Tsao & Ni, 2016). According to the “2021 Literature and Tourism Industry Dynamic Report,” due to travel restrictions and other policies following the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in December 2019, China's civil aviation passenger traffic has seen a sharp decline, down 84.3% year-on-year in February (Beh & Lin, 2022).

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) can be a costly investment for companies. Has COVID-19 had a negative impact on travel companies' CSR investments? The answer is not clear. CSR activities involve diverse company teams, including environmental, legal, economic, and human resources (Holder-Webb et al., 2009). According to relevant crisis management theories, long-term CSR investment has both cumulative and insurance effects, which improve enterprises’ reputations and anti-risk abilities (Tao & Song, 2020). The tourism industry is high-risk, high cost, highly competitive, and has low profit margins. Moreover, tourism products are non-essential, and their costs are considered to have low levels of stickiness (T. Li et al., 2018). Unlike other industries, CSR in the tourism industry is short-term, results-oriented, high-risk, and environmentally dependent (Inoue & Lee, 2011). Existing studies have shown that, from the perspective of corporate strategy, investing in CSR enhances a company's goodwill, brand image, proportion of intangible assets, resource sustainability, and sustainable operation (Henderson, 2007). In contrast, other previous studies based on over-investment theory have shown that investing in CSR can be seen as showboating behavior, resulting in a serious waste of resources (Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Friedman, 1970).

This study’s main research purpose is to examine how tourism companies adjusted CSR under the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic. It compares Chinese listed companies in the tourism and other industries from 2017 to 2021 based on stakeholder and cost stickiness theories. In addition, it systematically analyzes the moderating mechanisms of the COVID-19 epidemic shock on CSR in the tourism industry from the perspectives of multiple corporate strategies, including differentiation leadership, cost leadership, political connections, and organizational resilience. The study findings are as follows. First, the COVID-19 shock increased tourism firms’ strategic CSR and decreased their responsive CSR. Second, tourism firms that implemented cost leadership strategies reduced responsive CSR more than strategic CSR. Tourism firms that implemented differentiation strategies increased (decreased) strategic (responsive) CSR. Third, tourism firms with higher political connections increased responsive CSR. Finally, tourism companies with higher organizational resilience increased strategic CSR.

Compared with previous studies, this study’s main contributions are the following. First, using a quasi-natural experiment in China, the study reveals the theoretical mechanism through which CSR investments of listed tourism companies were adjusted in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic shock. Second, to consider the differences in cost stickiness levels between CSR types, we divide CSR into strategic and responsive CSR. Strategic CSR has a higher degree of cost stickiness than responsive CSR. This analysis provides a more detailed view of the CSR adjustment preferences of tourism companies. Third, the study also explores the moderating effects of different strategic orientations on adjustments in CSR investments in tourism enterprises. It systematically analyzes the impact of corporate strategies on tourism enterprises' CSR adjustments. Fourth, this study explores the moderating role of political connections on adjustments in responsive CSR investment among tourism enterprises. We scientifically analyze the impact of political connections on tourism enterprises’ CSR adjustments. Finally, the study explores the moderating role of organizational resilience in tourism firms’ strategic CSR investment adjustments and methodically analyzes how organizational resilience impacts tourism companies’ strategic CSR investment adjustments.

The study’s findings will help policymakers customize policies for tourism enterprises in the context of COVID-19 or other crisis events in ways that are consistent with tourism development principles and help tourism enterprises withstand difficult times. At the same time, it provides a decision-making basis for tourism firm managers to adjust their CSR investments for sustainable development during crises.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Strategic vs. Responsive CSR

According to institutional theory, to establish legitimacy and gain resource support, tourism firms’ CSR behaviors need to respond to institutional pressures while satisfying laws, industry rules, and stakeholder expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). According to strategy theory, CSR must also match a firm’s strategic objectives to maintain competitive advantage by absorbing valuable, scarce, and unique resources (Barney, 1991).

Given COVID-19’s impact, do travel companies reduce or maintain their CSR investments? The answer needs to be more specific that what current research offers. According to Porter and Kramer's social responsibility decision-making framework (2006), CSR can be subdivided into two types: responsive and strategic. Responsive CSR aims to improve short-term relationships with stakeholders (Michael E. Porter & Mark R. Kramer, 2006) and has been viewed as a token impression management activity or short-term investment separate from an organization's core business (Bansal et al., 2015; Muller & Kräussl, 2011). Strategic CSR, on the other hand, is a long-term oriented investment with limited short-term returns (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Kang, 2016); it requires long-term planning, a significant investment of resources, and major adjustments to an organization’s structure (Bansal et al., 2015). Thus, in the face of COVID-19, firms must weigh the costs of adjusting responsive and strategic CSR, such as economic losses and social relationship, contractual, psychological, and reputational costs, which are intangible and difficult to directly observe (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Venieris et al., 2015).

2.2. CSR Adjustments Based on the Cost Stickiness

Cost stickiness theory states that certain costs behave asymmetrically in response to changes in activity (Anderson et al., 2003; Venieris et al., 2015). When a company's business volume improves, sticky costs increase much more than they decrease when business volume declines (Anderson et al., 2003; Venieris et al., 2015). From a cost stickiness perspective, the cost stickiness of strategic and responsive CSR differs significantly (Habib et al., 2016). Strategic CSR focuses more on the intersection of corporate and social interests, integrating social responsibility into corporate strategy, resources, capabilities, processes, business models, and interactions with stakeholders (Owen & Kemp, 2023). In particular, strategic CSR, such as product and employee responsibility, requires long-term strategic programming, considerable investment of resources, and substantial organizational restructuring (Bansal et al., 2015). As a result, the costs of strategic CSR are stickier. If firms respond to the impact of COVID-19 by reducing strategic CSR, they face serious simultaneous losses, including stakeholder investment confidence and economic, social relationship, contract, and reputation costs (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Venieris et al., 2015). In other words, making strategic adjustments to cope with COVID-19’s impact by reducing strategic CSR investments does not pay off.

Responsive CSR aims to improve relationships with some stakeholders, meet certain stakeholder requirements in the short term, and conform to laws, industry regulations, and principles to build legitimacy and gain resource support. Responsive CSR is a symbolic and showy management activity; it is a short-term investment that departs from the organization’s core business (Bansal et al., 2015; Muller & Kräussl, 2011). Responsive CSR, such as community (charitable donations) and environmental responsibility (environmental protection inputs), are basic strategies used to cope with the institutional environment to gain legitimacy, as tools to pander to the government, or as fire-fighting tools to cope with an economic crisis (Cunha et al., 2021). In addition, based on agency theory’s over-investment hypothesis, CSR is an agency behavior that reflects management's self-interest; CEOs tend to over-invest in CSR at the expense of shareholders. This over-investment negatively affects firm value and may even become a huge cost that restricts firm development (Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Friedman, 1970). Compared to strategic CSR, responsive CSR is a short-term investment that is reversible, requires fewer resources, is less costly to adjust, and has a lower level of cost stickiness.

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a. Due to its high level of cost stickiness, tourism firms increase strategic CSR in the face of the COVID-19 shock.

H1b. Due to its low level of cost stickiness, tourism firms decrease responsive CSR in the face of the COVID-19 shock.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Cost or Differentiation Leadership Strategies

Moderating role of cost leadership strategy: Firms that implement cost leadership strategies strive to reduce costs to provide the lowest-priced products and services. For example, they establish efficient, large-scale production processes and introduce new technologies in parallel with production activities, as well as minimize research and development, advertising, marketing, and service costs (Gao & Feng, 2010). Implementing cost leadership strategies in emerging economies generates better financial performance than other leadership strategies, as firms derive comparative advantages from low labor and production costs. Low prices are more attractive to consumers with lower disposable income levels (Duanmu et al., 2018). Enterprises with cost leadership strategies generally maintain lower adjustment costs and more flexible cost structures (Datta, 2010; Haque et al., 2021). CSR activities of firms that implement cost leadership strategies have lower levels of cost stickiness and can therefore adjust their CSR quickly in the event of an external shock (J. Li et al., 2021).

Moderating role of differentiation leadership strategy: Previous research has shown that CSR can be a differentiation strategy tool. For example, Flammer's (2015) study shows that, in the face of increasing import competition, US firms will choose to invest in social responsibility to differentiate themselves from competing foreign firms (C. J. A. a. S. Flammer, 2015). Firms that implement a differentiation leadership strategy have been shown to focus on positive relationships with core stakeholders, gaining access to strategic resources such as reputation or moral capital (Restuti et al., 2023). Moreover, the CSR costs of firms that implement differentiated leadership strategies have higher levels of cost stickiness; such firms prefer to continue to maintain strategic CSR while reducing responsive CSR in the face of shocks (Kost et al., 2020; Salas-Vallina et al., 2021).

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2a. Tourism companies that implement cost leadership strategies decrease strategic or responsive CSR.

H2b. Tourism companies that implement differentiated leadership strategies decrease responsive CSR and increase strategic CSR.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Political Connections on Responsive CSR

In a transition economy, governments can develop and implement institutions, policies, and norms and are an essential source of resources and legitimacy. The relationship between businesses and government is crucial to business survival and growth (J. Zhang & Luo, 2013). Fehrler and Przepiorka argue that responsive social CSR signals firms' search for external legitimacy, arguing that firms should strategically implement legitimacy cost management when weighing legitimacy and profitability in response to external evaluations (Fehrler & Przepiorka, 2013).

A political connection can generally be thought of as a special informal relationship between a government and a business, where political power is formed between the business and governmental departments or individuals, the performance of top management (CEO, chairman), and significant shareholders of the business with experience in government service, or through public service and building networks and government relationships (Hillman, 2005; Hillman & Hitt, 1999). However, political connections are different from political bribery, as political connections are legal. Government experience gives them unique information about the workings of government (Hillman, 2005). As a result, they may be more likely to establish links with government officials, leading to more excellent government support for businesses. The resources that political connections bring to firms may reduce their legitimacy and institutional investment. Thus, to save resources, politically connected firms reduce philanthropic investment as a signaling cost of firm legitimacy.

Political connections signal legitimacy to stakeholders like governments, gaining support and close ties to governments and others (Bergh et al., 2014). This reduces the reversibility of responsive CSR; that is, it increases the level of CSR’s cost stickiness (Balakrishnan & Gruca, 2008; Habib & Hasan, 2019). Thus, when faced with the COVID-19 shock, more political connections may mitigate firms’ responsive CSR cuts.

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. Higher political connections mitigate tourism firm reductions in responsive CSR.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Organizational Resilience on Strategic CSR

Existing studies have shown that organizational resilience refers to several processes through which organizations resist impacts, absorb the harmful effects of influence, and achieve rapid recovery (M. DesJardine et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019). Strategic CSR for tourism firms concerns their strategic interests. Tourism firms will strengthen their interactions with strategic stakeholders when performing strategic social CSR activities to obtain competitive advantage and achieve sustainable development (Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006).

Investment in strategic CSR strengthens the connection between tourism firms and strategic stakeholders; enables tourism firms to obtain scarce resources closely related to their core business, thus supporting their defense systems in the face of crisis events; and enhances their stability and absorbability (M. DesJardine et al., 2019; Sajko et al., 2021; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2022). According to signal theory, firms can convey positive information about their stable and positive state to stakeholders through CSR investment to enhance stakeholders' resource support and investment confidence and enhance their ability to resist changes in the external environment (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003; M. R. DesJardine et al., 2021; Fama, 1980).

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4. High organizational resilience enhances tourism firms’ increase in strategic CSR

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

In this paper, listed companies in mainland China from 2017 to 2021 are selected to test the impact of COVID-19 epidemic shocks on the CSR of tourism companies. The sample size of this study is 13,747 after excluding samples with outliers and missing values.CSR data are obtained from the social responsibility data disclosed by Hexun.com. The financial data of control variables are from the China Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. To reduce the influence of outliers, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels.

3.2. Measures

The independent variable in this study is the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on tourism businesses (DID) (Kosfeld et al., 2021). The COVID-19 outbreak occurred in December 2019, so this paper assigns a value of 1 to the 41 listed tourism companies in mainland China in 2019 and after and 0 to the rest of the samples, noting this variable as DID. It should be noted that although the outbreaks recurred in various places after 2019, the recurrence of the subsequent episodes does not have the exact mechanism as that of the initial attacks. Initial seizures are more sudden and crisis-oriented than subsequent outbreaks, which is more in line with the assumptions of the double-difference model.

The dependent variables of this study are strategic CSR (SCSR) and responsive CSR (RCSR). Drawing on the methodology of previous researchers, strategic CSR is the sum of employee responsibility and product responsibility, and responsive CSR is the sum of environmental responsibility and community responsibility, which is derived from the social responsibility data of listed companies disclosed by Hexun.com (C. Flammer & Ioannou, 2021; Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006).

The moderating variables: cost leadership VS differentiation leadership strategies. The measurement of cost leadership (Cost_leadership) and differentiation leadership (Diff_leadership) strategies in this paper draws on the research design of Gao et al. (2010) and Duanmu et al. (2018) (Duanmu et al., 2018; Gao & Feng, 2010), where cost-leading strategies are measured by the ratio of the difference between sales and production costs to sales, with larger values indicating that a firm's cost leadership is more pronounced. The differentiation strategy is measured using the firm's advertising costs ratio to total sales. The data in this section comes from the CSMAR database .

The moderating variable: political connections. The political connection and ownership data in this paper came from the manual collation of the CSMAR database (Fan et al., 2007). A firm’s degree of political connection is denoted as GOV_level. Suppose the chairman or general manager of the firm has or currently holds posts in the government, the Party Committee (Commission for Discipline Inspection), the standing organs of the National People’s Congress or CPPCC, the procuratorate, and the court. In that case, the political association GOV_level is assigned to four levels. To be specific, the political connection level of section-level cadres is set as 1, the political connection level of section-level cadres is set as 2, the political connection level of department-level cadres is set as 3, the political connection level of ministerial-level and national-level cadres is set as 4, and the political connection level of no political connection is set as 0. Suppose the chairman or general manager of the firm used to or currently served as a party representative, a representative of the National People’s Congress, or a member of the CPPCC. In that case, the political connection GOV_level is also assigned to four levels. Specifically, the GOV_level of the political connection at the county level and below is 1, the GOV_level of the political connection at the municipal level is 2, the GOV_level of the political connection at the provincial level is 3, the GOV_level of the political connection at the national level is 4, and the GOV_level of the political connection without the political connection is 0. Suppose there is data for both political connection GOV_level and political connection GOV_level definitions. In that case, the maximum value of the two is taken as the value of the political connection level of the firm.

The moderating variable: organizational resilience. In this paper, organizational resilience is considered a two-dimensional structural variable with high-performance growth (Revenue_Growth) and low financial volatility (Finance_Volatility), referring to the methodology proposed by Ortiz to measure these two dependent variables (Ortiz-de-Mandojana & Bansal, 2016). The indicator used in this paper to measure high-performance growth is the amount of cumulative sales revenue growth over three years, as incremental growth is more indicative of the long term than year-to-year growth, and consistent with the research of many scholars, three years is chosen as the period to measure the long term growth of a firm. In this paper, financial volatility is measured by the volatility of stock returns, measured as the standard deviation of stock returns for each month of the year. In particular, the lower the value of Finance_Volatility, the lower the financial volatility and the more resilient the organization.

In order to control the influence of other factors, this paper starts from the firm level and draws on previous studies to select firm size

(Size), firm growth capacity

(Growth), leverage level

(Leverage), and cash flow

(Cashflow) as the control variables (Y. Zhang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2017). Referring to previous studies, this study used a double difference model for regression analysis as shown in equations (1) and (2).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 showed descriptive statistics of variables.

In order to test whether there is a strong correlation between the variables, we report and observe the matrix of correlation coefficients between two by two variables . It is easy to find that in

Table 2, the absolute value of correlation coefficients between variables is less than 0.7, so strong correlation between variables is excluded, indicating that there is no serious correlation between variables (Ali et al., 2009).

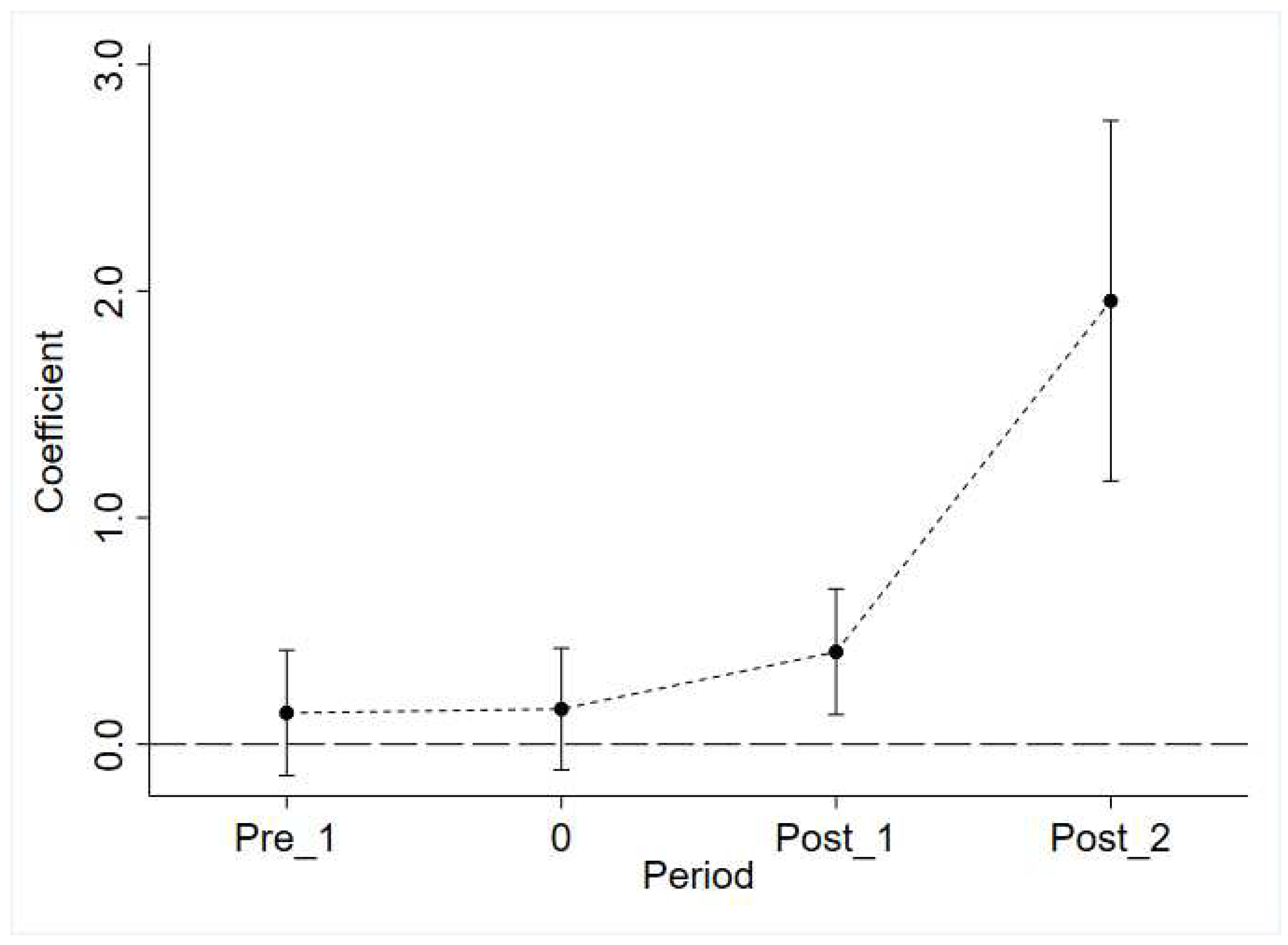

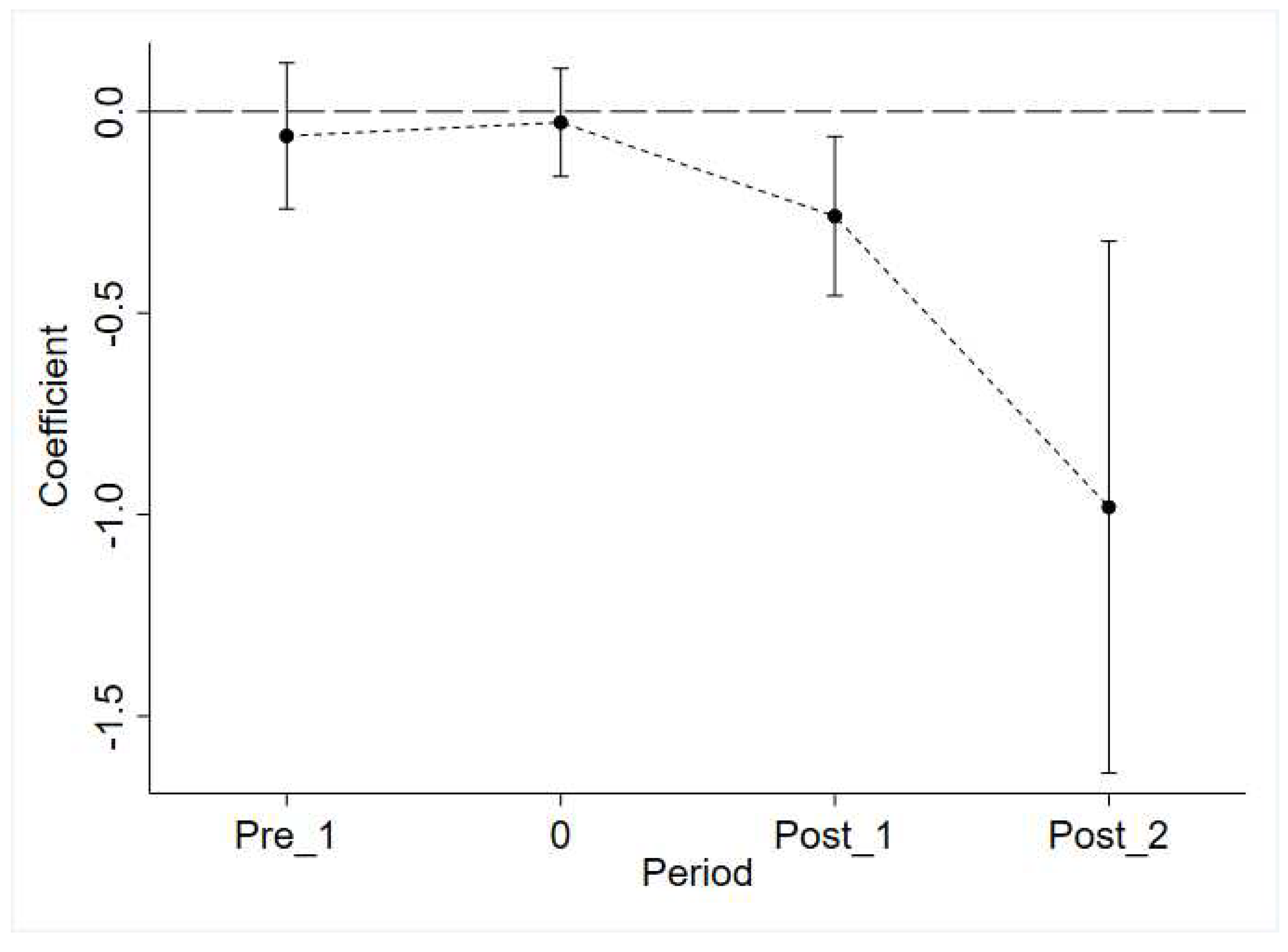

4.2. Parallel Trend Tests

Before carrying out the regression of the difference in difference (DID) model, this study needs to verify the parallel trend of the double difference model, as shown in

Table 3. The test results given in

Table 3, strategic CSR as the dependent variable, the regression coefficients for the period one before the epidemic shock ~ the period 0 are not significant, indicating that there is a parallel trend in the strategic CSR investment between the control group and the treatment group (Marcus et al., 2021). With the responsive CSR as the dependent variable, the regression coefficients for the period one before the epidemic shock ~ the period 0 are not significant, indicating that there is a parallel trend in the responsive CSR between the control group and the treatment group (Marcus et al., 2021). More intuitive results this study are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

4.3. Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on CSR in the Tourism Industry

The effects of the COVID-19 epidemic shock on strategic and responsive CSR are given in

Table 4, where this study controls for firm-fixed effects and time-fixed effects and control variables affecting socially responsible investment in the test. Model (1) and model (2) both use panel regression; model (1), with strategic CSR as the dependent variable, the regression coefficient of DID is significantly positive, which indicates that the COV-19 epidemic shock makes tourism enterprises increase investment in strategic CSR; model (2) with responsive CSR as the dependent variable, the regression coefficient of DID is significantly negative, which indicates that, under the COV-19 epidemic shock, tourism enterprises reduce the investment in responsive CSR, and H1 is verified.

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Tests of DID with a One-Period Lag

In this study, to verify the longer-term impact of the COVID-19 epidemic shock on tourism firms' investment in social responsibility, a robustness test was conducted using strategic and responsive CSR measures of socially responsible investment with a lag of one year, and the results of the test are shown in

Table 5 (Guo et al., 2022). The results in column (1) show that although one period of strategic CSR investment lags, the COVID-19 shock still positively contributes to it. Similarly, column (2) results show that although responsive CSR has faded by one period, it is still negatively weakened by the COVID-19 shock. In the above regressions, the positive and negative coefficients of DID are consistent with the benchmark regression, and H1 is validated, which proves that the results we obtain are robust.

4.4.2. Tests for Changing the Timing of COVID-19 Shocks

To further test the robustness of the results, this study conducts a counterfactual test by varying the timing of the dummy epidemic shocks, which excludes the effects of policy or stochastic factors other than the epidemic (Hong et al., 2022). By advancing the timing of the epidemic shock by one year, if the regression coefficients of the variables representing the effect of the epidemic shock are not significant at this point, the additional impact of other policy factors can be excluded. As shown in

Table 6, the results of the counterfactual test indicate that if the epidemic shock is assumed to have occurred one year earlier, neither strategic nor responsive CSR is significantly affected, which suggests that other factors do not cause the adjustments in strategic and responsive CSR, but instead come from the COVID-19 epidemic shock.

5. Further Researches

5.1. Moderating Effects of Corporate Strategies on CSR

As shown in

Table 7, firms implementing cost leadership strategies decrease both strategic and responsive CSR, H2a is proved. Firms implementing differentiation strategies increase strategic CSR and decrease responsive CSR, H2b is proved.

5.2. Moderating Effects of Political Connections on Responsive CSR

As shown in

Table 8, tourism with a higher degree of political affiliation mitigated the reduction in responsive CSR, as evidenced by H3.

5.3. Moderating Effect of Organizational Resilience on Strategic CSR

As shown in

Table 9, both high levels of performance growth and low levels of financial volatility reinforce the increase in strategic CSR of tourism firms, as evidenced by H4.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

6.1. Main Conclusions

The main findings of this study are as follows. First, based on the quasi-natural experiment of the COVID-19 epidemic, we compare the tourism industry with other industries and find that the COVID-19 epidemic shock causes tourism firms to increase strategic CSR and decrease responsive CSR significantly. Second, tourism firms implementing cost leadership strategies cut both strategic and responsive CSR but cut responsive CSR to a greater extent. Tourism firms implementing differentiation leadership strategies increase strategic CSR and decrease responsive CSR. Again, tourism firms with higher levels of political affiliation mitigated reduced responsive CSR. Finally, tourism firms with higher organizational resilience reinforced increased strategic CSR.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

First, this study introduces the cost stickiness theory as a basis for tourism firms to adjust their strategic and responsive CSR investments, which further enriches the application scenarios of the cost stickiness theory. This study draws on the social responsibility decision-making framework constructed by Porter and Kramer (2006), which categorizes CSR into responsive and strategic (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006). Previous studies have shown that cost stickiness theory suggests that certain costs are sticky and that these costs increase more asymmetrically when a firm's business volume rises than they decrease when business volume falls (Anderson et al., 2003; Venieris et al., 2015). The findings of this study test and confirm the differentiation hypothesis of cost stickiness of different dimensions of social responsibility. This study demonstrates that when faced with COVID-19 shocks, tourism firms maintain or even increase strategic CSR investments due to high-cost stickiness. On the contrary, due to low-cost stickiness, tourism firms will cut back on responsive CSR investments. The findings of this study help to clarify further the controversy about the motivation of Chinese tourism firms to fulfill their social responsibility from the perspective of cost stickiness.

Second, this paper incorporates corporate strategy into a model of the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the social responsibility of tourism firms, further revealing the boundary mechanisms of the effects of the COVID-19 epidemic on the social responsibility of tourism firms. Similar to previous studies on corporate strategy (Duanmu et al., 2018; C. J. A. a. S. Flammer, 2015), this paper analyzes the moderating mechanisms of cost-leading and differentiation-leading strategies on the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic shock and tourism CSR. This study finds that firms implementing differentiated leadership strategies promote strategic CSR, while firms implementing low-cost leadership strategies reduce strategic or responsive CSR. Our findings shed further light on the moderating mechanisms by which tourism firms adjust their social responsibility in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic.

Third, adding a political connection to the model of the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and tourism CSR further reveals the moderating mechanism of the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and tourism CSR. Unlike previous studies on political connection (Balakrishnan & Gruca, 2008; Habib & Hasan, 2019), this paper finds that political connection makes responsive CSR challenging to reduce, raising the cost stickiness of responsive CSR. So, we find that a high level of political connection increases the responsive CSR of tourism firms. Therefore, this study further enriches and expands the explanatory scope of cost stickiness theory from the perspective of political connection.

Finally, organizational resilience is incorporated into the model of the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and tourism CSR, which further reveals the regulating mechanism of the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and tourism CSR. Unlike previous studies on organizational resilience (Ortiz-de-Mandojana & Bansal, 2016), this paper analyzes the moderating mechanism of organizational resilience on the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and tourism CSR. This study finds that because organizational resilience is related to the core business of tourism enterprises, the formation of organizational resilience requires long-term investment. Tourism firms with higher levels of organizational resilience have higher cost stickiness, so they increase strategic CSR. Therefore, this study further enriches and extends the explanatory scope of cost stickiness theory from the perspective of organizational resilience.

Author Contributions

Hao WANG: conceptualization, methodology, literature analysis, theoretical analysis, data organization and analysis, writing. Tao ZHANG: conceptualization, thematic guidance, literature analysis, theoretical analysis, financial support. Xi WANG: validation, data investigation, writing-review and editing. Jiansong ZHENG: conceptualization, literature analysis, data analysis, theoretical analysis, editing and writing. You ZHAO: conceptualization, literature analysis, theoretical analysis, editing. Rongjiang CAI: literature analysis, theoretical analysis, editing. Xia LIU: literature analysis, editing. Qiaoran JIA: literature analysis, theoretical analysis. Zehua ZHU: conceptualization, theoretical analysis. Xiaolong JIANG: conceptualization, editing.

Funding

This study is supported by the Research Project of Macao Polytechnic University (RP/ESCHS-04/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Hexun Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of A-share Listed Companies, China Stock Market & Accounting Research database (CSMAR), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Beijing Hexun Online Information Consulting Service Company Limited (Hexun Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of A-share Listed Companies), Shenzhen CSMAR Data Technology Company Limited (CSMAR).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all research staff that contributed to the data collection required for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. We confirm that all authors have approved the manuscript for submission.

References

- Ali, N., Jusof, K., Ali, S., Mokhtar, N., & Salamat, A. S. A. (2009). THE FACTORS INFLUENCING STUDENTS’PERFORMANCE AT UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MARA KEDAH, MALAYSIA. Management Science and Engineering, 3(4), 81-90.

- Anderson, M. C., Banker, R. D., & Janakiraman, S. N. (2003). Are Selling, General, and Administrative Costs “Sticky”? [https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00095]. Journal of Accounting Research, 41(1), 47-63. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R., & Gruca, T. S. (2008). Cost stickiness and core competency: A note. Contemporary Accounting Research, Forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P., Jiang, G. F., & Jung, J. C. (2015). Managing Responsibly in Tough Economic Times: Strategic and Tactical CSR During the 2008–2009 Global Recession. Long Range Planning, 48(2), 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A., & Rubin, A. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility as a Conflict Between Shareholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 71-86. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L. A., & Fried, J. M. (2003). Executive compensation as an agency problem. Journal of economic perspectives, 17(3), 71-92. [CrossRef]

- Beh, L.-S., & Lin, W. L. J. J. o. A. P. P. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on ASEAN tourism industry. 15(2), 300-320. [CrossRef]

- Bergh, D. D., Connelly, B. L., Ketchen Jr, D. J., & Shannon, L. M. (2014). Signalling theory and equilibrium in strategic management research: An assessment and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 51(8), 1334-1360. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F. A. F. d. S., Meira, E., Orsato, R. J. J. B. S., & Environment, t. (2021). Sustainable finance and investment: Review and research agenda. 30(8), 3821-3838. [CrossRef]

- Datta, Y. J. C. B. R. (2010). A critique of Porter's cost leadership and differentiation strategies. 9(4), 37.

- DesJardine, M., Bansal, P., & Yang, Y. (2019). Bouncing back: Building resilience through social and environmental practices in the context of the 2008 global financial crisis. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1434-1460. [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M. R., Marti, E., & Durand, R. (2021). Why activist hedge funds target socially responsible firms: The reaction costs of signaling corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Journal, 64(3), 851-872. [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. J. A. s. r. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, J. L., Bu, M., & Pittman, R. J. S. M. J. (2018). Does market competition dampen environmental performance? Evidence from China. 39(11), 3006-3030. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of political Economy, 88(2), 288-307. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. P., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China's newly partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(2), 330-357. [CrossRef]

- Fehrler, S., & Przepiorka, W. (2013). Charitable giving as a signal of trustworthiness: Disentangling the signaling benefits of altruistic acts. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(2), 139-145. [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C., & Ioannou, I. (2021). Strategic management during the financial crisis: How firms adjust their strategic investments in response to credit market disruptions. Strategic Management Journal. [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. J. A. a. S. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and the allocation of procurement contracts: Evidence from a natural experiment.

- Friedman, M. (1970). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. New York Times Magazine.

- Gao, Q.-x., & Feng, Q.-q. (2010). Research on the organizational model and human resource management based on advanced manufacturing technology. (Ed.),^(Eds.). 2010 IEEE 17Th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management.

- Guo, Q., Zhong, J. J. T. F., & Change, S. (2022). The effect of urban innovation performance of smart city construction policies: Evaluate by using a multiple period difference-in-differences model. 184, 122003. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., & Hasan, M. M. (2016). Corporate Social Responsibility and Cost Stickiness. Business & Society, 58(3), 453-492. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., & Hasan, M. M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and cost stickiness. Business & Society, 58(3), 453-492. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Hasan, M. M. J. A., & Research, B. (2016). Auditor-provided tax services and stock price crash risk. 46(1), 51-82. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. G., Munawaroh, M., Sunarsi, D., & Baharuddin, A. J. P. D. R. (2021). Competitive Advantage in Cost Leadership and Differentiation of SMEs “Bakoel Zee” Marketing Strategy in BSD. 4(2), 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. C. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and tourism: Hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 228-239. [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J. (2005). Politicians on the board of directors: Do connections affect the bottom line? Journal of management, 31(3), 464-481. [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., & Hitt, M. A. (1999). Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. Academy of management review, 24(4), 825-842. [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, L., Cohen, J. R., Nath, L., & Wood, D. J. J. o. b. e. (2009). The supply of corporate social responsibility disclosures among US firms. 84, 497-527. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y., Ma, F., Wang, L., & Liang, C. J. R. P. (2022). How does the COVID-19 outbreak affect the causality between gold and the stock market? New evidence from the extreme Granger causality test. 78, 102859. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y., & Lee, S. J. T. m. (2011). Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. 32(4), 790-804. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., & Verreynne, M. L. (2019). Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 882-900. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. (2016). Labor market evaluation versus legacy conservation: What factors determine retiring CEOs' decisions about long-term investment? [https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2234]. Strategic Management Journal, 37(2), 389-405. [CrossRef]

- Kosfeld, R., Mitze, T., Rode, J., & Wälde, K. J. J. o. R. S. (2021). The Covid-19 containment effects of public health measures: A spatial difference-in-differences approach. 61(4), 799-825. [CrossRef]

- Kost, D., Fieseler, C., & Wong, S. I. J. H. R. M. J. (2020). Boundaryless careers in the gig economy: An oxymoron?, 30(1), 100-113. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Luo, Z. J. M., & Economics, D. (2021). Product market competition and cost stickiness: Evidence from China. 42(7), 1808-1821. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Liu, J., Zhu, H., & Zhang, S. J. A. P. J. o. T. R. (2018). Business characteristics and efficiency of rural tourism enterprises: an empirical study from China. 23(6), 549-559. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M., Sant’Anna, P. H. J. J. o. t. A. o. E., & Economists, R. (2021). The role of parallel trends in event study settings: An application to environmental economics. 8(2), 235-275. [CrossRef]

- Muller, A., & Kräussl, R. (2011). Doing good deeds in times of need: a strategic perspective on corporate disaster donations [https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.917]. Strategic Management Journal, 32(9), 911-929. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Bansal, P. J. S. M. J. (2016). The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. 37(8), 1615-1631. [CrossRef]

- Owen, J. R., & Kemp, D. J. J. o. E. M. (2023). A return to responsibility: A critique of the single actor strategic model of CSR. 341, 118024. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: the link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92, 163.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. J. H. b. r. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. 84(12), 78-92.

- Restuti, M. D., Gani, L., Shauki, E. R., Leo, L. J. B. S., & Development. (2023). Cost stickiness behavior and environmental uncertainty in different strategies: Evidence from Southeast Asia. [CrossRef]

- Sajko, M., Boone, C., & Buyl, T. (2021). CEO greed, corporate social responsibility, and organizational resilience to systemic shocks. Journal of management, 47(4), 957-992. [CrossRef]

- Salas-Vallina, A., Alegre, J., & López-Cabrales, Á. J. H. R. M. (2021). The challenge of increasing employees' well-being and performance: How human resource management practices and engaging leadership work together toward reaching this goal. 60(3), 333-347. [CrossRef]

- Tao, W., & Song, B. J. P. R. R. (2020). The interplay between post-crisis response strategy and pre-crisis corporate associations in the context of CSR crises. 46(2), 101883. [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.-y., & Ni, C.-c. J. T. G. (2016). Vulnerability, resilience, and the adaptive cycle in a crisis-prone tourism community. 18(1), 80-105. [CrossRef]

- Venieris, G., Naoum, V. C., & Vlismas, O. (2015). Organisation capital and sticky behaviour of selling, general and administrative expenses. Management Accounting Research, 26, 54-82. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Kosmala, M. (2022). A study of the tourism industry's cash-driven resilience capabilities for responding to the COVID-19 shock. Tourism Management, 88, 104396. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Luo, X. R. (2013). Dared to care: Organizational vulnerability, institutional logics, and MNCs’ social responsiveness in emerging markets. Organization Science, 24(6), 1742-1764. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, H., & Zhou, X. J. A. o. M. J. (2020). Dare to be different? Conformity versus differentiation in corporate social activities of Chinese firms and market responses. 63(3), 717-742. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E. Y., Fisher, G., Lounsbury, M., & Miller, D. J. S. M. J. (2017). Optimal distinctiveness: Broadening the interface between institutional theory and strategic management. 38(1), 93-113. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).