Submitted:

30 January 2024

Posted:

01 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject Demographics

2.2. MRI Scans

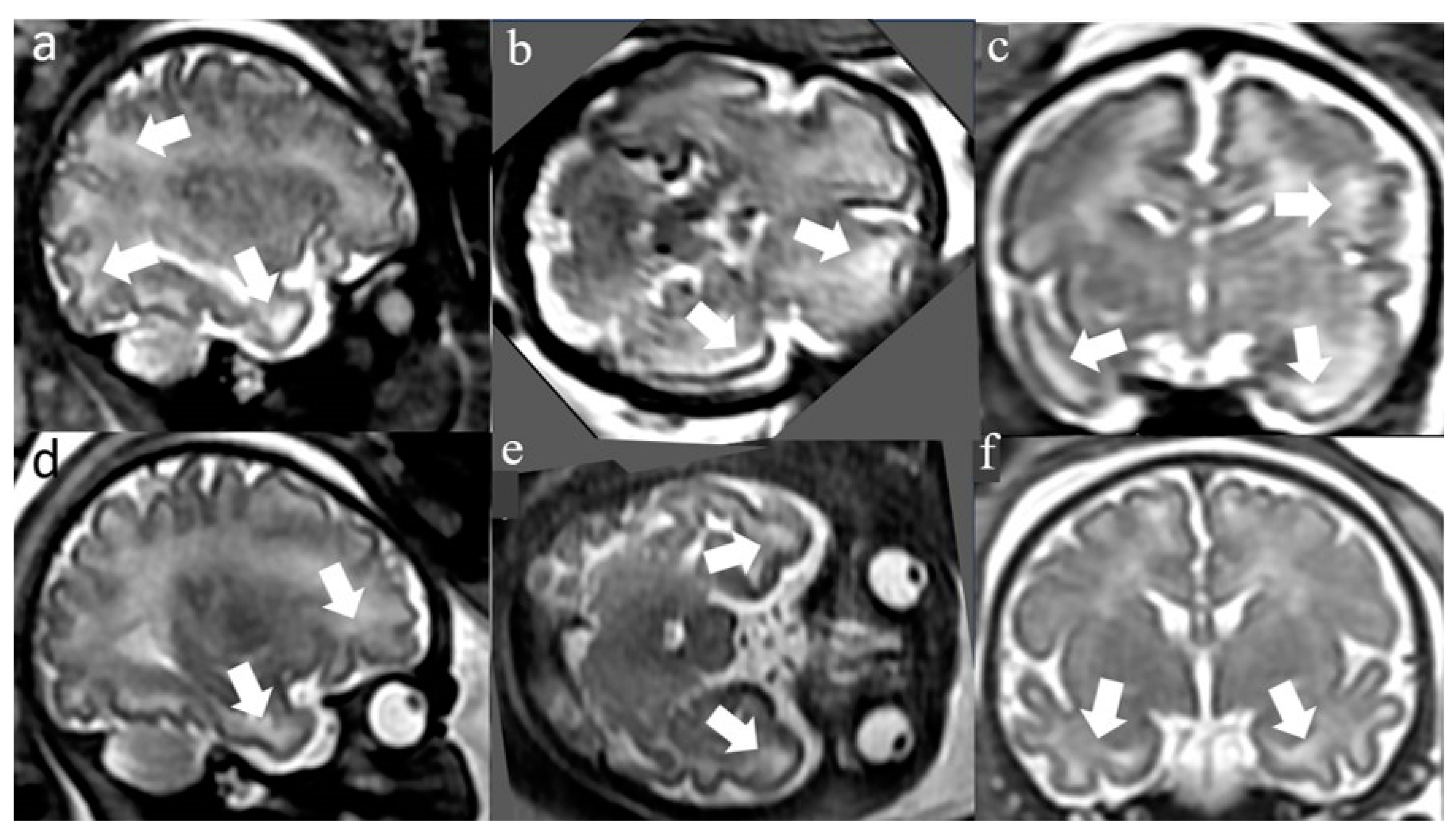

2.3. White Matter T2 Hyperintense Signal (WMHS)

2.4. Interobserver Validity of Measurements

2.5. Neuro-developmental assessment

2.4. Hearing evaluation

2.8. Ethics Approval

2.9. Funding:

2.10. Informed Consent Statement:

2.11. Conflicts of Interest:

3. Results

Maternal and pregnancy demographic, clinical, and imaging characteristics

3.2. Postnatal clinical and imaging characteristics

3.3. Long-term neuro-developmental and hearing outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maltezou, P.G.; Kourlaba, G.; Kourkouni, Ε.; Luck, S.; Blázquez-Gamero, D.; Ville, Y.; Lilleri, D.; Dimopoulou, D.; Karalexi, M.; Papaevangelou, V. Maternal type of CMV infection and sequelae in infants with congenital CMV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, S.C.; Grosse, S.D.; Ross, D.S. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppana, S.B.; Ross, S.A.; Fowler, K.B. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2013, 57 Suppl 4, S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneson, A.; Cannon, M.J. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, W.D.; Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Lazzarotto, T.; Alain, S.; Daly, K.; Doutré, S.; Gibson, L.; Giles, M.L.; et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e177–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Walle, C.; Keymeulen, A.; Oostra, A.; Schiettecatte, E.; Dhooge, I.; Smets, K.; Herregods, N. Apparent diffusion coefficient values of the white matter in magnetic resonance imaging of the neonatal brain may help predict outcome in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr. Radiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, A.M.H.; Smith, R.J.H.; Camp, G.V.; Schleiss, M.R.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.A.K.; Lustig, L.R.; Usami, S.; Boudewyns, A.N. Congenital hearing loss. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2017, 3, 16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.J. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) epidemiology and awareness. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goderis, J.; Leenheer, E.D.; Smets, K.; Hoecke, H.V.; Keymeulen, A.; Dhooge, I. Hearing loss and congenital CMV infection: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, A.S.; Lanzieri, T.M.; Claussen, A.H.; Vinson, S.S.; Turcich, M.R.; Iovino, I.R.; Voigt, R.G.; Caviness, A.C.; Miller, J.A.; Williamson, W.D.; et al. Intelligence and Academic Achievement With Asymptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Pediatrics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, D.W.; Jester, P.M.; Sánchez, P.J.; Ahmed, A.; Arav-Boger, R.; Michaels, M.G.; Ashouri, N.; Englund, J.A.; Estrada, B.; Jacobs, R.F.; et al. Valganciclovir for symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, L.S.D.; Gunardi, H.; Barth, P.G.; Bok, L.A.; Verboon-Maciolek, M.A.; Groenendaal, F. The spectrum of cranial ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Neuropediatrics 2004, 35, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katorza, E.; Strauss, G.; Cohen, R.; Berkenstadt, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Achiron, R.; Barzilay, E.; Bar-Yosef, O. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Levels and Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Fetuses with Brain MR Imaging White Matter Hyperintense Signal. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimiot, F.; Garel, C.; Fallet-Bianco, C.; Menez, F.; Khung-Savatovsky, S.; Oury, J.-F.; Sebag, G.; Delezoide, A.-L. Contribution of diffusion-weighted imaging in the evaluation of diffuse white matter ischemic lesions in fetuses: correlations with fetopathologic findings. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaniv, G.; Katorza, E.; Bercovitz, R.; Bergman, D.; Greenberg, G.; Biegon, A.; Hoffmann, C. Region-specific changes in brain diffusivity in fetal isolated mild ventriculomegaly. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teissier, N.; Fallet-Bianco, C.; Delezoide, A.-L.; Laquerrière, A.; Marcorelles, P.; Khung-Savatovsky, S.; Nardelli, J.; Cipriani, S.; Csaba, Z.; Picone, O.; et al. Cytomegalovirus-induced brain malformations in fetuses. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, N.; Hoffmann, C.; Ben-Sira, L.; Lev, D.; Schweiger, A.; Kidron, D.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Malinger, G. Does normal fetal brain ultrasound predict normal neurodevelopmental outcome in congenital cytomegalovirus infection? Prenat. Diagn. 2011, 31, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoist, G.; Salomon, L.J.; Mohlo, M.; Suarez, B.; Jacquemard, F.; Ville, Y. Cytomegalovirus-related fetal brain lesions: comparison between targeted ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 32, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipitz, S.; Hoffmann, C.; Feldman, B.; Tepperberg-Dikawa, M.; Schiff, E.; Weisz, B. Value of prenatal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in assessment of congenital primary cytomegalovirus infection. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 36, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, R.; Ben-Sira, L.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Malinger, G. The use of fetal neurosonography and brain MRI in cases of cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy: A retrospective analysis with outcome correlation. Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gat, I.; Hoffmann, C.; Shashar, D.; Yosef, O.B.; Konen, E.; Achiron, R.; Brandt, B.; Katorza, E. Fetal Brain MRI: Novel Classification and Contribution to Sonography. Ultraschall Med. Stuttg. Ger. 1980 2016, 37, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannie, M.M.; Devlieger, R.; Leyder, M.; Claus, F.; Leus, A.; Catte, L.D.; Cossey, V.; Foulon, I.; Valk, E.V. der; Foulon, W.; et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: contribution and best timing of prenatal MR imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 3760–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F.; Cloud, G.; Britt, W.J.; Henderson, R.E.; Walton, P.D.; Veren, D.A.; Page, F.; Alford, C.A. Primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Incidence, transmission to fetus, and clinical outcome. JAMA 1986, 256, 1904–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlfors, K.; Forsgren, M.; Ivarsson, S.A.; Harris, S.; Svanberg, L. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: on the relation between type and time of maternal infection and infant’s symptoms. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1983, 15, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liesnard, C.; Donner, C.; Brancart, F.; Gosselin, F.; Delforge, M.L.; Rodesch, F. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: prospective study of 237 pregnancies at risk. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heibel, M.; Heber, R.; Bechinger, D.; Kornhuber, H.H. Early diagnosis of perinatal cerebral lesions in apparently normal full-term newborns by ultrasound of the brain. Neuroradiology 1993, 35, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinger, G.; Lev, D.; Sira, L.B.; Kidron, D.; Tamarkin, M.; Lerman-Sagie, T. Congenital periventricular pseudocysts: prenatal sonographic appearance and clinical implications. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 20, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevey-Macherel, M.; Forcada Guex, M.; Bickle Graz, M.; Truttmann, A.C. Neurodevelopment outcome of newborns with cerebral subependymal pseudocysts at 18 and 46 months: a prospective study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.; Bar-Yosef, O.; Berkenstadt, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Achiron, R.; Katorza, E. Prenatal Evaluation, Imaging Features, and Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Prenatally Diagnosed Periventricular Pseudocysts. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016, 37, 2382–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoul, I.R.; Zmora, O.; Tamir, A.; Shahar, E.; Sujov, P. Congenital subependymal pseudocysts: own data and meta-analysis of the literature. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. IMAJ 2001, 3, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Faqi, A.S.; Klug, A.; Merker, H.J.; Chahoud, I. Ganciclovir induces reproductive hazards in male rats after short-term exposure. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1997, 16, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Normal MRI | WMHS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years, mean (SD) | 32.5 (4.1) | 30.9 (4.7) | 0.191 |

| Gestational age at MRI, median (IQR) | 34 (32-35) | 33 (33-34) | 0.593 |

| Pregnancy number, median (IQR) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 0.670 |

| Labor number, median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1.75) | 0.652 |

| Abnormal outcome in previous labors, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 0.052 |

| Abnormal maternal medical background, n (%) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (4.8) | >0.999 |

| Spontaneous conception, n (%) | 28 (82.4) | 21 (100) | 0.072 |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 13 (35.1) | 11 (52.4) | 0.200 |

| Abnormal nuchal translucency scan, n (%) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (5.3) | >0.999 |

| Abnormal 1st trimester biochemical test, n (%) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Abnormal 2nd trimester biochemical test, n (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Abnormal early anatomical scan, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Abnormal late anatomical scan, n (%) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (4.7) | >0.999 |

| Infection week, median (IQR) | 17 (11-23) | 8 (6.5-19.5) | 0.015 |

| Clinical and radiological findings | Normal MRI (N=37) |

WMHS (N=21) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of pregnancy (weeks), median (IQR) | 39 (37.6-39.9) | 39.3(38.4-39.9) | 0.633 |

| Birth weight, (gr) median (IQR) | 3114 (2878-3410) | 3052 (2845-3420) | 0.974 |

| Birth weight (percentile), median (IQR) | 52 (32-73) | 41 (29.5-73.5) | 0.840 |

| Head circumference (cm), median (IQR) | 34 (33-35) | 34 (33-35) | 0.647 |

| Head circumference (percentile), median (IQR) | 51 (12-79) | 54 (29-80) | 0.510 |

| Head circumference < 10%, n (%) | 1 (11%) | 5(14.3%) | >0.999 |

| SEPC in head ultrasound. n (%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (21%) | 0.043 |

| LSV in head ultrasound, n (%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (21%) | 0.426 |

| Any abnormal finding in head US, n (%) | 5 (14%) | 6 (29%) | 0.296 |

| Abnormal acoustic emissions, n (%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | >0.999 |

| Abnormal Auditory Brain response (after birth), n(%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (4.8%) | >0.999 |

| Valganciclovir Treatment, n (%) | 4 (11%) | 14 (67%) | <0.001 |

| Clinical and radiological findings |

Normal MRI (N=37) |

WMHS (N=21) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at VABS, (years), median (IQR) | 2.3 (1.5-3.5) | 3.8 (2.5-4.5) | 0.049 |

| VABS motor skills, median (IQR) | 100.5 (77.5-105.3) | 106 (97-116.3) | 0.032 |

| VABS daily living skills, median (IQR) | 109 (99.25-115.3) | 105 (97.5-116.8) | 0.641 |

| VABS socialization skills, median (IQR) | 106 (100.3-114) | 107 (97.3-116) | 0.501 |

| VABS communication skills, median (IQR) | 103 (100.8-107.3) | 102 (94.3-108.8) | 0.469 |

| VABS adaptive score composite, median (IQR) | 102.5 (94-111.3) | 106 (98.3-110) | 0.233 |

| Hearing impairment; n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.7) | >0.999 |

| Multivariate Regression | Motor Standard Score | Social Standard Score | Daily Skills Standard Score | Communication Standard Score | General Standard Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope* (CI) | p-value | Slope* (CI) | p-value | Slope*(CI) | p-value | Slope* (CI) | p-value | Slope* (CI) | p-value | |

| Constant | 103 | 99 | 105 | 105 | 103 | |||||

| Infection week (week) | 4.8 (-1.7 - 4.1) |

0.26 | -2.6 (-4.6 - 4.1) |

0.91 | -1.0 (-7.8 – 5.8) |

0.76 | 2.7 (-3.7 – 9.2) |

0.39 | 1.8 (-1.7 – 7.5) |

0.51 |

| WMHS+/ Valganciclovir- |

-22.2 (-34.7 - -11.3) |

0.001 | 2.1 (-2.0 – 8.1) |

0.49 | -3.6 (-13.0 – 5.7) |

0.44 | -0.8 (-9.7 – 8.1) |

0.85 | -7.6 (-15.3 – 0.1) |

0.051 |

| WMHS-/ Valganciclovir+ |

-4.2 (-19.0 – 10.5) |

0.56 | 3.7 (-5.1 – 10.2) |

0.51 | -9.1 (-20.1 – 2.7) |

0.13 | -9.8 (-21.0 – 1.4) |

0.08 | -6.5 (-16.2 – 3.2) |

0.18 |

| WMHS+/ Valganciclovir+ |

0.4 (-9.5 – 10.5) |

0.93 | 2.5 (0.5 – 10.8) |

0.03 | -3.8 (-4.1 – 11.5) |

0.34 | 2.9 (-4.6 – 10.5) |

0.45 | 3.9 (-2.6 – 10.5) |

0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).