1. Investigating the Potential Double Edged Score of Immigration-Related Stress, Discrimination and Mental Health Access

Discrimination and immigration-related stress appear to increase mental health symptomology across multiple domains, including depression and PTSD symptoms 1–4. Despite the increase in symptomology and potential need for services, both discrimination and immigration-related stress may increase avoidance of healthcare systems for Latinx populations, especially immigrants and those close to them5,6. Based on healthcare utilization models, like the Health Belief Model7,8, this may place many Latinx populations in a double bind wherein discrimination and immigration-related stress prompt greater need for care but also impede access to that care. The current study will investigate these compounding relationships based on the Health Belief Model in a predominantly immigrant sample of Latinx residents in the Midwest. It also extends prior work as most research examining the effects of discrimination on mental health symptoms, PTSD in particular, focus on African American/Black populations9,10.

2. The Health Belief Model and the Potential Roles of Discrimination and Immigration Stress

The Health Belief Model is a theoretical model outlining the factors that prompt health behavior change7. Much of the research on the Health Belief Model has focused specifically on healthcare utilization11,12. The model overall outlines six factors as necessary for healthcare utilization: 1) perceived susceptibility, 2) perceived severity, 3) perceived benefits, 4) perceived barriers, 5) cue to action, and 6) self-efficacy7. Of these, only perceived barriers would impede attempts to care while each of the other five would decrease care-seeking behaviors. In a mental health utilization context, perceived benefits will necessarily include the perceived benefits of seeking treatment and of treatment itself. Said differently, this is the perception that available/accessible treatment will be effective in addressing symptoms. Relatedly, self-efficacy in this case would include the perceived ability to access treatment and perform the tasks involved during treatment.

As outlined in more detail elsewhere13, discrimination may operate to both diminish perceived effectiveness of services and to increase perceived barriers to care by increasing the social cost of care. This applies to both discrimination in general, given the lack of representation in healthcare, and discrimination in healthcare settings specifically. Immigration-related stress may operate in a similar fashion in that many factors involved in immigration-related stress may increase multiple perceived barriers, including financial and social costs5. From prior literature, these costs may include fear of deportation and fear of unfair treatment in healthcare settings5,14. Both fear of deportation and fear of unfair treatment in healthcare due to immigration status may prompt avoidance of mental health utilization14. Although much of this literature has focused on undocumented immigrants, such fear may extend to other Latinx immigrants and those close to them (e.g., fear of deportation of a loved one). Further, due to assumptions surrounding immigration status, many Latinxs born in the U.S. may also experience several immigration-related stressors. Further, the effects of immigration-related stress have less often been examined quantitatively and not within the context of the Health Belief Model.

In contrast to immigration-related stress and discrimination, symptom recognition for both PTSD and depression is a necessary component of perceived severity, which would be posited to increase utilization. Thus, self-reporting of symptoms is a direct indicator of perceived severity. Taken together with the extant literature on the effects of discrimination on depression and PTSD3,9,15–17, this suggests that these symptoms may therefore operate as potential mediators of a positive indirect effect of discrimination on seeking mental health care. Testing this indirect effect among Latinx populations would represent a novel addition to the research literature and potentially add nuance regarding the conflicting roles of discrimination on care access.

Though examined less frequently, immigration-related stress may operate similarly. Prior work has indicated that immigration-related stress is associated with higher depression symptoms1,4. Immigration-related stress may also exacerbate PTSD symptoms, though this has been examined less frequently. Theoretically, components immigration-related stress for Latinx immigrant populations and those around them may exacerbate symptoms such as hypervigilance, avoidance and hyperarousal. This may result from persistent fears of deportation or challenges fulfilling essential life functions because of immigration status (e.g., transportation because of fear of police interactions).

3. Purpose

The current study sought to quantitatively examine the potential dual roles of discrimination and immigration-related on mental health care seeking. First, it examined the direct effects of both factors in potentially reducing care seeking and subsequently care utilization. Second, it examined the indirect effects of both factors with PTSD and depression symptoms as potential mediators. It was hypothesized that both discrimination and immigration-related stress would have negative direct effects on mental health care seeking and care utilization. It was further hypothesized that both discrimination and immigration-related stress would evidence positive indirect effects on care seeking and care utilization with PTSD and depression symptoms as mediators. Specifically, discrimination and immigration-related stress would have positive direct effects on depression and PTSD symptoms. Depression and PTSD symptoms would in turn have positive direct effects on care seeking and care utilization.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

Participants were 234 Latinx residents of the Midwest from cities and towns of population sizes ranging from approximately 5,000 to approximately 300,000. The majority were born outside the U.S. (n=197; 87.2%) and cisgender women (n=165; 70.2%). The largest proportion of participants were born in Mexico (n=91; 38.7%), followed by Cuba (n=37; 15.7%), Guatemala (n=25; 10.1%), Honduras (n=14; 5.9%), and Colombia (n=10; 4.2%). Fewer than 10 participants were born in El Salvador, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Argentina. Average age was 42.52 years. The majority of participants indicated they completed a high school degree or more (n=178; 78.1%).

4.2. Procedure

Participants were recruited separately through phone and internet surveys. For the phone surveys, participants were recruited through multiple local community agencies who served Latinx populations. Participants were also recruited via respondent-driven sampling, in which existing participants were offered incentives for recruiting additional participants ($10 gift card for each participant recruited). Prior participants who not informed as to who completed the survey to preserve confidentiality of participation. Recruitment for the phone survey occurred from November 2020 through August 2021. Recruitment for the internet survey occurred through a university extension agency, which provides education and resources to the local community. Recruitment for the internet wave occurred from January to April 2022. In both cases, surveys were completed as a larger study focusing on COVID-19, stress exposure, mental health, and healthcare access. In both internet and phone surveys, participants were able to complete the study in either English or Spanish. These procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at [blinded].

4.3. Measures

Discrimination. Discrimination was measured using two questionnaires. The six-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS)18 was used to measure general experiences of discrimination in multiple contexts and the seven-item Discrimination in Medical Settings scale (DMS)19. The DMS was derived from the EDS such that it represents a context-specific version of the EDS19. Both scales have demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent validity18–21. Both have also been used to measure experiences of discrimination in Latinx samples18. The EDS demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .96) as did the DMS (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Immigration-Related Stress. Immigration-related stress was measured using the five-item Lack of Legal Immigrant Status subscale from the Stress of Immigration Survey22. Only this subscale was used due to brevity. Items assess common fears related to precarious immigration status for the participant with multiple items also referencing difficulties for family members. Items ask participants “how much stress or worry (they) have experienced” as a result of fear they or a family may be deported, not having the correct documents when accessing services, not having a license to drive, difficulties accessing healthcare for the participant or family because of documentation, and difficulties returning to visit their home country. As such, many of these items apply to undocumented as well as documented immigrants and their family. The scale evidenced strong internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .95).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD was measured using an abbreviated version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-523. The PCL-5 assesses symptoms of PTSD taken directly from the DSM-5 diagnosis and asks participants to rate their frequency from “not at all” (0) to “Extremely” (4). The PCL-5 has demonstrated good internal consistency23. A Spanish language version has also evidenced good internal consistency with Mexican and Central American samples24,25. An abbreviated version was used to accommodate requests for brief surveys from recruitment partners and to minimize study burden. Five items were initially included (Item B1-Intrusive thoughts, Item B4-Emotional Cue Reactivity, Item C1-Avoidance of external reminders, Item E1-Irritability or anger, and Item E4-Easily startled. However, confirmatory factor analyses indicated that Item E4 had only a moderately loading onto a single item factor (λ=.49) and removing it yielded good model fit across most indicators, χ2 (2) = 0.32, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .001 (90% CI = <.01 - .07), and SRMR = .01. Thus, only four items (B1, B4, C1 and E1) were included in the present analyses.

Depression. Depression symptoms were assessed using a modified version of the nine-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is among the most widely used measures of depression, including in several large international studies of depression26–29. The PHQ-9 typically contains nine items, but the final item regarding suicidality was removed so that the study could be more readily administered in an online context. This modification has been used in prior studies where the measure still demonstrates strong internal consistency and concurrent reliability30. The Spanish translation of the PHQ-9 has also demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent validity28,29. The eight-item version demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Mental Health Access. Mental health access was measured using two items. The first asked participants if they had sought services since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but were unable to receive them. The second asked if participants were currently receiving services. These two items therefore represent unsuccessful attempts to receive care and current mental health use, respectively. Participants answered either “yes” or “no”, which were then dichotomously coded as “1” and “0” respectively. As part of exploratory follow-up questions, participants who indicated they had been unable to receive services were asked to identify barriers that prevented them from receiving care.

Demographics. Participants also completed items regarding gender, age, U.S. nativity/country of origin, and education.

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Information.

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Information.

| |

n (%) |

| Gender |

|

|

|

| Cisgender women |

165 (70.2) |

| Cisgender men |

65 (27.7) |

| Transgender men |

1 (0.4) |

| Born outside the U.S. |

197 (83.8) |

| Mexico |

91 (38.7) |

| Caribbean |

39 (16.6) |

| Central America |

45 (19.1) |

| South America |

23 (9.8) |

| Education |

|

|

|

| Less than high school |

50 (21.3) |

| Completed high school |

86 (36.6) |

| Some college or higher |

92 (39.1) |

| Unsuccessfully Sought Mental Health Care |

21 (8.9) |

| Currently Receiving Care (yes) |

21 (8.9) |

| |

M (SD) |

Min-Max |

| Age |

42.52 (14.21) |

19-82 |

| Annual Household income (in USD) |

42,596 (33,963) |

0 -200,000 |

| PHQ-8 (Depression Symptoms) |

7.12 (5.50) |

0-24 |

| Abbreviated PCL-5 (PTSD Symptoms) |

2.41 (3.11) |

0-14 |

| Everyday Discrimination |

5.26 (4.88) |

0-20 |

| Discrimination in Healthcare |

12.09 (2.98) |

4-20 |

| Immigration-Related Stress |

38.15 (9.21) |

16-58 |

4.4. Data Analyses

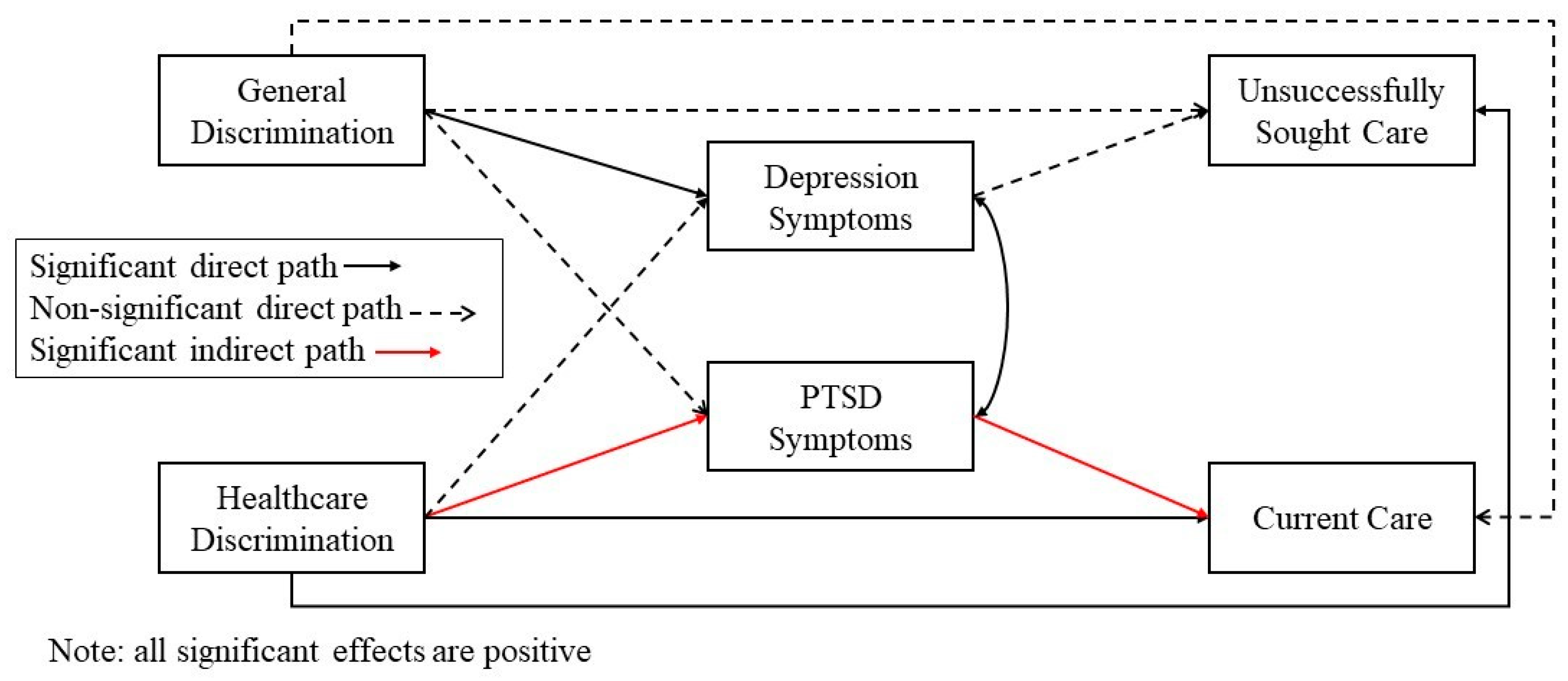

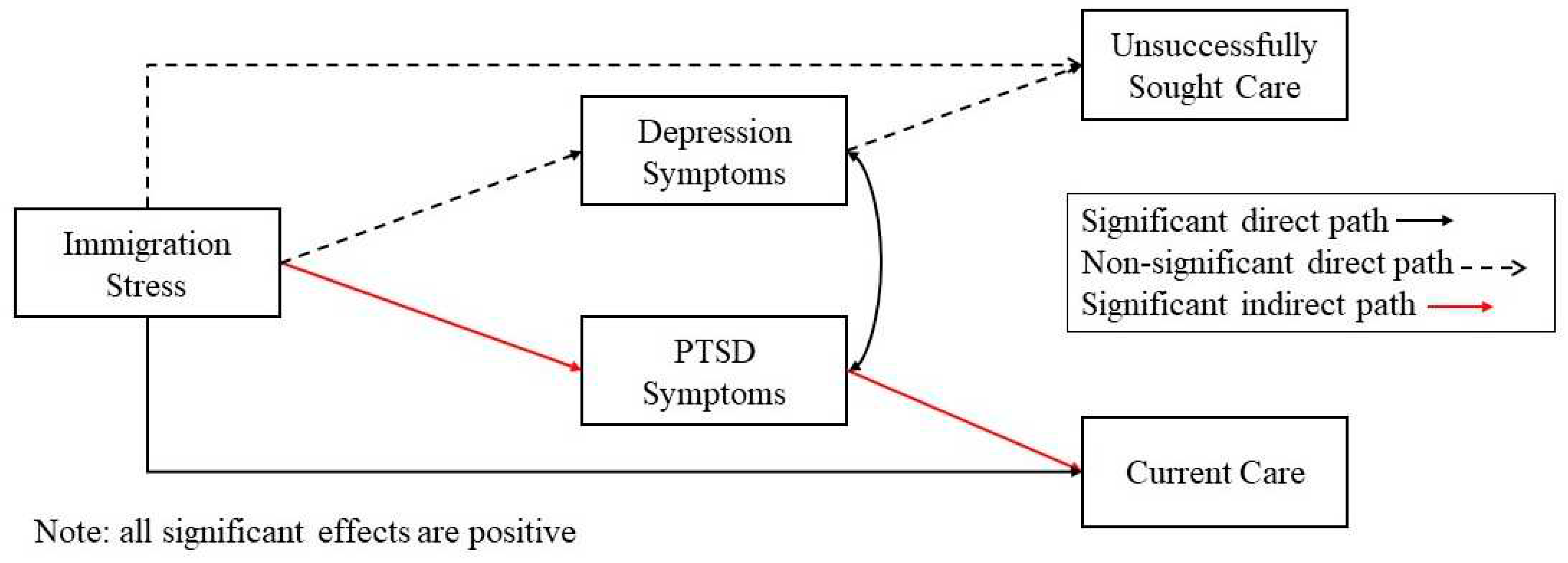

Study hypotheses were tested using two separate path models in which depression and PTSD symptomology were examined as mediators between experiences of discrimination (model 1)/immigration stress (model 2) and the two mental health utilization variables. These models are depicted in Figure 1. To test specific hypotheses, the direct effects of discrimination/immigration stress variables on both PTSD and depression were examined, as were the direct effects of PTSD and depression on both mental healthcare access variables and the constituent indirect effects. Additionally, the direct effects of discrimination variables on mental healthcare access variables were also tested. Age, gender, and education were included as covariates in the model. Significance for all effects, including indirect effects, was examined using bootstrapped confidence intervals with 500 sample draws. Because the model includes two dichotomous variables as outcomes and a mediational structure, Monte Carlo integration was used and frequently used model fit indices (e.g., CFI) are not available. However, the mediational models were compared against simpler models using log likelihood ratio tests. Specifically, it was compared against two models with no mediational paths in which symptomology were either only outcomes (with only discrimination as predictors) or only predictors (with only healthcare access variables as outcomes. The mediational model was not significantly different from either of the two simpler models (p-values > .05). Thus, given the specific hypotheses regarding the indirect role of symptomology, the mediational model was retained and included here.

Figure 1.

Path Model of Direct and Indirect Effects of Discrimination on Mental Health Access.

Figure 1.

Path Model of Direct and Indirect Effects of Discrimination on Mental Health Access.

Figure 2.

Path Model of Direct and Indirect Effects of Immigration Stress on Mental Health Access.

Figure 2.

Path Model of Direct and Indirect Effects of Immigration Stress on Mental Health Access.

Prior to completing analyses, analytic assumptions and missing data were assessed. Only items from the EDS evidenced significant missingness (>10% missing). All missing data were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation, which has been associated with reduced bias relative to other methods31. All other analytic assumptions were met.

5. Results

5.1. Discrimination as Predictors of PTSD and Depression

In the discrimination model, discrimination in healthcare settings was positively associated with PTSD symptoms, b = .15, 95% CI = .07, .25, but was not associated with depression symptoms, b = .10, 95% CI = -.01, .23. General experiences of discrimination were negatively associated with depression, b = -.32, 95% CI = -.38, -.26, but was not associated with PTSD symptoms, b = -.03, 95% CI = -.08, .02. No other variable was associated with depression (i.e., all other confidence intervals included zero). Gender was associated with PTSD symptoms, such that women reported more symptoms than men, b = 1.23, 95% CI = .28, 2.23. No other variable was associated with PTSD symptoms (i.e., all other confidence intervals included zero).

5.2. Immigration Stress as Predictors of PTSD and Depression

In the immigration stress model, immigration stress positively predicted PTSD symptoms, b = .12, 95% CI = .05, .18, but was not associated with depression symptoms, b = .004, 95% CI = -.10, .10.

5.3. Direct Effects on Mental Health Access Variables

PTSD and Depression Symptoms as Predictors

In the discrimination model, PTSD symptoms were positively associated with having unsuccessfully sought mental health services, aOR = 1.18, b = .16, 95% CI = .03, .38, but depression symptoms were not significantly associated with having unsuccessfully sought services, b = -.03, 95% CI = -.18, .09. PTSD symptoms were also positively associated with currently receiving care, aOR = 1.16, b = .15, 95% CI = .01, .34. Depression symptoms were not significantly associated with currently receiving mental health services, b = .08, 95% CI = -.06, .23. These results did not significantly differ in the immigration stress model.

Table 2.

Predictors of Mental Health Access Variables.

Table 2.

Predictors of Mental Health Access Variables.

| Predictor |

Dependent Variables |

|

| |

Unsuccessfully Seeking Care |

Current Care Utilization |

| |

aOR |

aOR |

| Gender |

0.85 |

0.77 |

| April 15 |

0.78 |

1.10 |

| Everyday Discrimination |

1.00 |

1.01 |

| Healthcare Discrimination |

1.11* |

1.09* |

| Depression Symptoms (PHQ-8) |

0.97 |

1.08 |

| PTSD symptoms (PCL) |

1.16* |

1.18* |

| Immigration-Related Stress |

1.03 |

0.99 |

5.4. Discrimination Variables as Predictors of Access Variables

General discrimination was not associated with either unsuccessfully seeking or currently receiving mental health services (confidence intervals include zero). Discrimination in healthcare settings was positively associated with currently receiving mental health services, aOR = 1.11, b = .10, 95% CI = .04, .21. Discrimination in healthcare settings was not associated with unsuccessfully seeking mental health services, aOR = 1.09, b = .09, 95% CI = -.004, .19.

5.5. Immigration Stress as Predictors of Access Variables

Immigration stress did not predict either currently receiving, aOR = 0.99, b = -.01, 95% CI = -.08, .06, or unsuccessfully seeking mental health services, aOR = 1.03, b = .03, 95% CI = -.03, .10.

5.6. Indirect Effects with Symptomology as Mediators

Because the direct effects of discrimination on PTSD and PTSD on both mental health service access variables were significant, their resulting indirect effects were tested. A similar pattern was also observed for immigration stress with resulting indirect effects. The indirect effect of discrimination on unsuccessfully seeking care with PTSD as a mediator was significant and positive, b = .02, 95% CI = .01, .07. The indirect effect of discrimination on currently receiving care with PTSD as a mediator was also significant and positive, b = .02, 95% CI = .001, .05. The indirect effect of immigration stress on unsuccessfully seeking care with PTSD as a mediator was also significant, b = .11, 95% CI = .04, .19. The indirect effect on currently receiving care was also significant, b = .09, 95% CI = .02, .18.

6. Discussion

The current study examined the potential double-edged sword of discrimination and immigration-related stress. Specifically, the study examined the potential for two opposing effects of discrimination and immigration-related stress on care access: a direct pathway with a lower likelihood of seeking care and an indirect pathway with symptoms as a mediator and a greater likelihood of seeking care. Results testing these hypotheses were mixed. Specifically, general discrimination was only associated with depression symptoms, but not PTSD. Conversely, healthcare discrimination and immigration stress were only associated with PTSD, but not depression. Further, discrimination in healthcare settings was associated with currently receiving care, but in the opposite direction than was anticipated. In fact, experiencing discrimination in healthcare settings was associated with higher odds of currently receiving care. General discrimination and immigration-related stress were not directly associated with either help seeking variable.

Overall, these results support only the indirect pathway of discrimination and immigration stress being associated with seeking or receiving mental health services. Relatedly, these effects only occurred via PTSD symptoms and not depression. This fits with other research indicating that experiences of discrimination may uniquely predict PTSD symptoms9. However, it differs from prior work in that only discrimination in healthcare settings, but not more broadly, predicted PTSD. It is unclear why general discrimination was not associated with PTSD. It is also unclear why immigration stress was only associated with PTSD. It may be that immigration stress results in significant anxiety and avoidance, specifically. Further, the fact that only PTSD consistently predicted care seeking or access may be explained in multiple ways. First, PTSD may not be treated as successfully as depression, as prior work indicates that those with PTSD often do not receive adequate care with greater disparities for Latinx populations32. Thus, depression and PTSD may both prompt service access, but PTSD these results may reflect the difficulty in treating PTSD and/or lack of access to appropriate care for PTSD. This, however, does not explain results in which depression did not predict unsuccessfully seeking care as unsuccessfully seeking care would not be presumed to result in symptom improvement. Better explaining this pattern of results and linking to the Health Belief Model, depression may result in both greater perceived symptom severity and lower perceived effectiveness of treatment. In other words, they may recognize the symptoms as problematic, which should prompt greater help seeking, but not have confidence that treatment will improve these symptoms, which would prompt less help seeking according to the Health Belief Model.

The direct effect was largely unsupported and only in the opposite direction that was predicted. This directly conflicts with the Health Belief Model, especially given that discrimination in healthcare was associated with greater care access and seeking. One potential reason for the positive effect of healthcare discrimination on currently receiving care may be related to the cross-sectional nature of this study. Specifically, contact with the mental healthcare system or other referring healthcare systems may produce experiences of discrimination. Thus, those who access care may also be more likely experience discrimination, which may in turn lead to worse PTSD symptomology. Longitudinal research is needed to fully explicate these relations. However, the pattern from the current cross-sectional data may reflect an underlying bidirectional relation in which PTSD increases the likelihood of seeking or receiving care and contact with the healthcare system results in discrimination, which then worsens PTSD symptomology leading to an increased need for care. Instead of a double-edged sword healthcare discrimination may place some in a double bind where the system intended to help alleviate symptoms may worsen these symptoms when discrimination is present.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

The current study should be considered in the context of multiple limitations. First, the lack of longitudinal data make it difficult to disentangle effects of discrimination on healthcare access and to fully test mediation. Second, the study’s convenience sample may limit generalization to other Latinx populations. While the inclusion of a sample recruited outside of any major metropolitan areas may extend the literature, healthcare systems may differ significantly in these areas, including the extent to which people experience discrimination and other available resources. Relatedly, the sample is primarily cisgender women and sample size was insufficient to test gender differences across the effects examined here. Given gender differences in both symptomology and help-seeking, results may differ for cisgender men and trans or gender diverse populations. However, the current results point to potentially fruitful areas of investigation, including longitudinal examination of discrimination, healthcare access, and help seeking behavior.

8. Conclusions

The current study suggests that discrimination in healthcare settings and immigration-related stress may increase PTSD symptoms, which in turn may prompt attempts to access care. The same effects were not present for depression symptoms. This offers new insights into the unique role of PTSD symptoms as consequences of stressors among Latinx populations and immigrants in particular.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our community partners, El Centro de las Américas, in the completion of this study.

References

- Andrews, A.R., III; Haws, J.K.; Acosta, L.M.; et al. Combinatorial effects of discrimination, legal status fears, adverse childhood experiences, and harsh working conditions among Latino migrant farmworkers: Testing learned helplessness hypotheses. J Latinx Psychol. 2020, 8, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, D.L.; Smith, Q.; Lanier, P. Racial discrimination and other adverse childhood experiences as risk factors for internalizing mental health concerns among Black youth. J Trauma Stress. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Budhwani, H.; Hearld, K.R.; Chavez-Yenter, D. Depression in Racial and Ethnic Minorities: the Impact of Nativity and Discrimination. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, M.J.; Norton, C.K. Demands of Immigration, Health Literacy, and Depression in Recent Latino Immigrants. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2010, 22, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, B.N.; Giordano, T.P.; Kim, J.H. Sociocultural and structural barriers to care among undocumented Latino immigrants with HIV infection. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012, 14, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.N.; Fang, H.; Perez, V.H.; et al. Health Care Access, Use of Services, and Experiences Among Undocumented Mexicans and Other Latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P. The health belief model. Predict Health Behav Res Pract Soc Cogn Models. 2015, 2, 30–55. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The health belief model. Health Behav Health Educ Theory Res Pract. 2008, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Holliday, S.; Dubowitz, T.; Haas, A.; Ghosh-Dastidar, B.; DeSantis, A.; Troxel, W.M. The association between discrimination and PTSD in African Americans: exploring the role of gender. Ethn Health. 2020, 25, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Printz, D.; DeLapp, R.C. Assessing racial trauma with the Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale. Psychol Violence. 2018, 8, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, E.J.; Freedman-Doan, C.R. Conceptualizing mental health care utilization using the health belief model. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2009, 16, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.; Sullivan, G.; Chavira, D.A.; et al. Race and beliefs about mental health treatment among anxious primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013, 201, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canchila, M.; Reyes, S.; Estrada Gonzalez, S.M.; et al. The role of discrimination and vaccine distrust in vaccine uptake among Latines in the Midwest. Behav Ther. Published online 2022. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2023-15394-001 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Hacker, K.; Anies, M.E.; Folb, B.; Zallman, L. Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: a literature review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy, Published online October 2015:175. [CrossRef]

- Brabeck, K.M.; Cardoso, J.B.; Chen, T.; et al. Discrimination and PTSD among Latinx immigrant youth: The moderating effects of gender. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, C.L.; Xie, D.; Meca, A.; Schwartz, S.J. Acculturation, discrimination, and depression among unauthorized Latinos/as in the United States. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2017, 23, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Ong, A.D. A daily diary investigation of Latino ethnic identity, discrimination, and depression. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2010, 16, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, D.J.; Fortuna, L.; Alegría, M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, M.E.; Nunez-Smith, M.; Drum, M.; Lewis, T.T. Adapting the Everyday Discrimination Scale to Medical Settings: Reliability and Validity Testing in a Sample of African American Patients. Ethn Dis. 2011, 21, 502–509. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky, B.D.; Gottfredson, N.C.; Panter, A.T.; Daye, C.E.; Allen, W.R.; Wightman, L.F. An item factor analysis and item response theory-based revision of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2011, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.J.; Forsythe-Brown, I.; Mouzon, D.M.; Keith, V.M.; Chae, D.H.; Chatters, L.M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among black Caribbeans in the United States: the impact of nativity and country of origin. Ethn Health. 2019, 24, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, R.M.; Nápoles, A.M.; Gregorich, S.; Paul, S.; Lee, K.A.; Stewart, A.L. Development of the Stress of Immigration Survey (SOIS): a Field Test among Mexican Immigrant Women. Fam Community Health. 2016, 39, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Graff, L.E.; Guzman, J.C.; Hare, T. Psychometric Properties of the CES-D, PCL-5, and DERS in a Honduran Adult Sample. Psychol Test Adapt Dev. 2023, 4, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Levy, G.A.; Bermúdez-Gómez, J.; Merlín-García, I.; et al. After a disaster: Validation of PTSD checklist for DSM-5 and the four- and eight-item abbreviated versions in mental health service users. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 305, 114197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The Phq-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulsin, L.; Somoza, E.; Heck, J. The Feasibility of Using the Spanish PHQ-9 to Screen for Depression in Primary Care in Honduras. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002, 4, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Gelaye, B.; Fann, J.R.; Sanchez, S.E.; Williams, M.A. Cross-cultural validity of the Spanish version of PHQ-9 among pregnant Peruvian women: a Rasch item response theory analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014, 158, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, C.K.; Bandalos, D.L. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Model. 2001, 8, 430–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClendon, J.; Dean, K.E.; Galovski, T. Addressing Diversity in PTSD Treatment: Disparities in Treatment Engagement and Outcome Among Patients of Color. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020, 7, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).