1. Introduction

The release of AI-powered ChatGPT has rapidly become a grounding for discourse within educational circles, especially those in higher education sectors worldwide. Since its launch in late 2022, ChatGPT has been the subject of intense examination, fueling debates concerning its potential as a transformative educational aid against its ability to enable academic misconduct, particularly plagiarism, and the promulgation of false information (Lund et al., 2023). The ethical implications of its use, including the potential for AI to impact student learning and the authenticity of their work, pose substantial concerns (Bringula, 2023; Essel et al., 2022). These ethical challenges have significantly influenced the hesitancy in ChatGPT’s full-scale adoption within academic frameworks. Nevertheless, the utility of ChatGPT in educational contexts cannot be overstated. Roose (2023) points out the advantages it offers, particularly in terms of resource generation and engagement facilitation, which could redefine the pedagogical mechanism. Such tools have the potential to revolutionize content creation, offering an excess of resources and interactive experiences that can support personalized learning paths (Fui-Hoon Nah et al., 2023). Furthermore, educators have found that when leveraged judiciously, ChatGPT can serve as a facilitator for idea generation and curriculum development (Meron & Araci, 2023), potentially enhancing the educator’s role by automating administrative tasks and allowing for more focused pedagogical strategies. The dualistic nature of ChatGPT’s impact—its prospective benefits shadowed by ethical and integrity-related quandaries—underscores the need for an in-depth examination of its role and regulation in educational settings. This dialogue is not merely theoretical but is being actively shaped by the experiences and testimonies of educators and students navigating this new technological frontier (Dwivedi et al., 2023).

The integration of ChatGPT into educational frameworks has also catalyzed a robust debate among academics and practitioners. Advocates, including Kocoń et al. (2023), sign ChatGPT as a revolutionary aid that enables educators to rapidly generate diverse teaching materials, thus potentially transforming pedagogical approaches. Such support hinges on the belief that ChatGPT’s responsive and interactive capabilities can significantly reduce the time and effort traditionally required for educational content creation. However, this optimistic view is counterbalanced by critical voices within the academic community. Critics, as voiced by De Angelis et al. (2023) and Deiana et al. (2023), caution against the adoption of ChatGPT without stringent oversight. Their primary concerns revolve around the ease with which students might exploit the tool for cheating and the propagation of misinformation, which threatens to compromise the integrity and reliability of educational standards. These apprehensions highlight a need for frameworks that can effectively mitigate such risks while preserving the beneficial aspects of AI in education.

Existing body of knowledge has yet to fully explore ChatGPT’s impact on User Information Satisfaction in higher education, leaving critical aspects such as information completeness, precision and all others satisfaction factors are underexamined. This oversight leads to educators and policymakers relying on incomplete data when considering ChatGPT’s potential and its effects on education. A comprehensive analysis of ChatGPT’s role in satisfying informational needs is vital for its effective application in educational settings. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct targeted studies that assess both the benefits and drawbacks of ChatGPT usage. Such investigations will clarify AI’s implications for UIS and help ensure that its integration into educational practices optimizes learning while upholding academic standards.

This study ventures to bridge this gap by systematically assessing how ChatGPT meets the informational needs of its users in higher education. It scrutinizes seven key dimensions of User Information Satisfaction — completeness, precision, timeliness, convenience, format, accuracy, and reliability — which have been underexplored in existing literature. Completeness pertains to the extent to which ChatGPT provides information that meets the full scope of users’ inquiries. Precision refers to the degree of specificity and relevance that ChatGPT’s responses hold to the questions posed. Timeliness involves the speed at which ChatGPT delivers information, while convenience considers the ease of interaction with the AI tool. Format examines the organization and presentation of information, and accuracy and reliability address the correctness and dependability of the content provided. This comprehensive evaluation, accounting for the positive potentials and risks identified by Foroughi et al. (2023), Strzelecki (2023), and Menon & Shilpa (2023), as well as the integrity concerns highlighted by Cotton et al. (2023), Bin-Nashwan et al. (2023), Liu et al. (2023), and Ansari et al. (2023), seeks to offer an expansive perspective on ChatGPT’s effectiveness and to elucidate its role in the academic sector. Through this investigation, the study aims to significantly advance the conversation surrounding the deployment of AI in education and to underpin its practical applications with robust empirical insights.

Revisiting the User Information Satisfaction framework by Ives et al. (1983), this study zeroes in on the integration of AI in education through ChatGPT. It investigates how ChatGPT’s accuracy, relevance, and timeliness can improve educational quality, focusing on the underexplored area of UIS in AI-supported learning environments. Amid growing concerns over the misuse of AI for unethical academic practices, the study provides actionable strategies for educational institutions to maximize ChatGPT’s benefits while upholding academic integrity (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Lo, 2023; Baek & Kim, 2023). It also offers a critical analysis of the risks associated with ChatGPT, particularly in facilitating academic dishonesty (Rivas & Zhao, 2023), which is indispensable for embedding AI into educational frameworks. By providing a robust evaluation of UIS in AI educational tools, the study equips decision-makers with the insights needed for informed AI integration and endorses a mindful adoption of AI to bolster learning outcomes, ensuring user satisfaction remains paramount.

2. Theoretical Framework

Previous studies have established a variety of User Information Satisfaction measures tailored to the context and specific information systems (IS) under scrutiny. For instance, Galletta and Lederer (1989) devised as many as 23 metrics to assess user satisfaction concerning the implementation and efficacy of IS. Conversely, Laumer et al. (2017) pinpointed four factors that determine user contentment with corporate content management systems, among other diverse inquiries (refer to Ives et al., 1983; Laumer et al., 2017; Bai et al., 2008). These scholarly endeavors elucidate that a theoretical framework for measuring UIS is well-established. However, there is a distinct lack of focus on measuring UIS specifically for AI-supported systems like ChatGPT. Therefore, this research aims to develop specialized UIS measures for ChatGPT, providing valuable insights for both users and developers, including entities like OpenAI and others engaged in chatbot technologies. This initiative not only broadens the scope of UIS application but also contributes to the refinement of AI-supported systems to better meet user requirements. The formulation of these measures has the potential to significantly influence the customization and enhancement of technology, thus elevating user utility and satisfaction across various contexts.

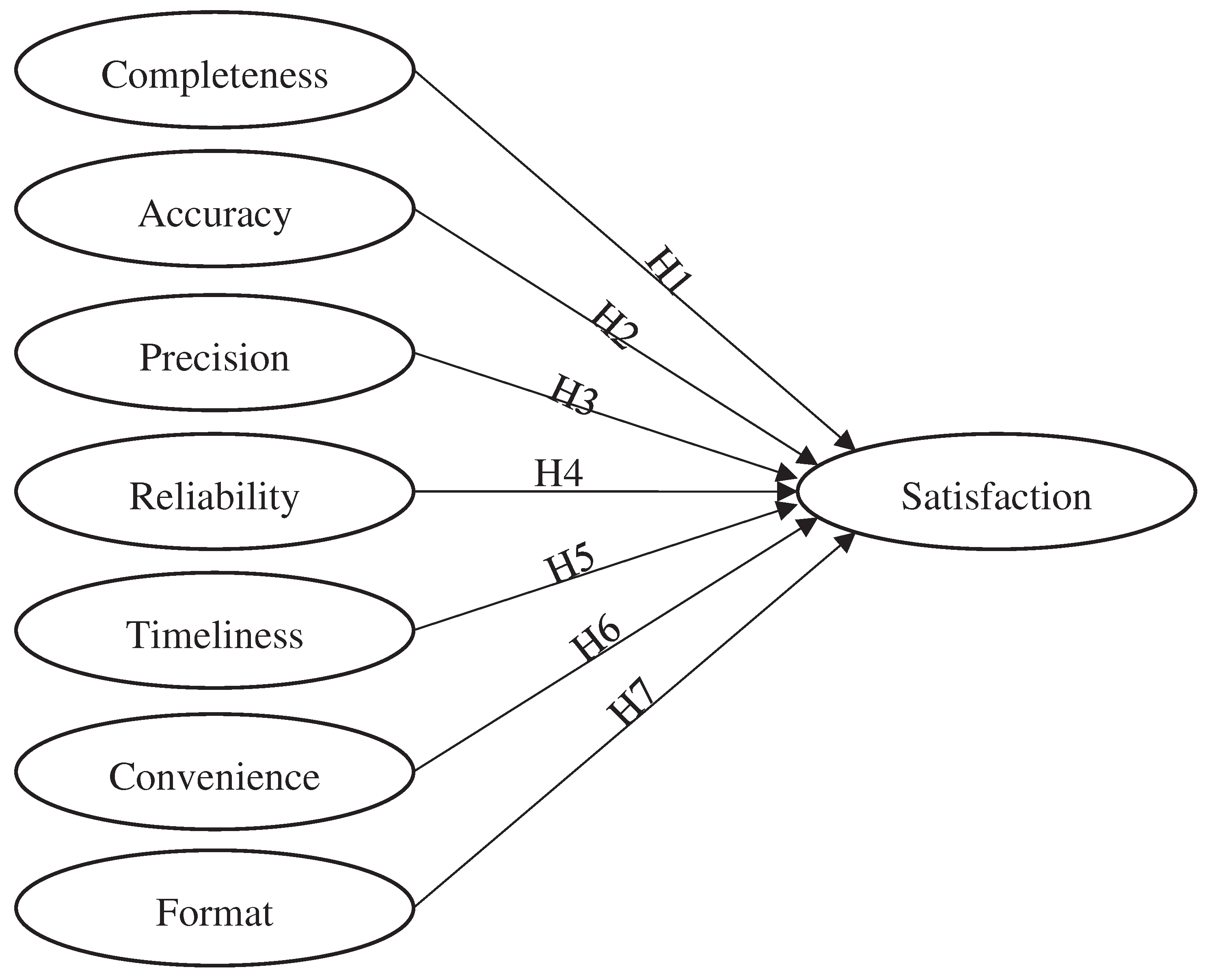

Drawing upon the concept of User Information Satisfaction from prior research (Foroughi et al., 2023; Ives et al., 1983; Laumer et al., 2017), this study formulates a seven-step framework to evaluate the ChatGPT system, which will be empirically tested among its users. These seven constructs of UIS have been operationalized into a user satisfaction model, methodically tested through this investigation. The UIS dimensions tailored for ChatGPT include completeness, precision, timeliness, convenience, format, accuracy, and reliability. These constructs will be assessed in relation to user satisfaction and structured within a conceptual research framework, as depicted in

Figure 1. This comprehensive approach aims to offer a holistic understanding of user interaction with and perception of the ChatGPT system. By analyzing these varied dimensions, the study endeavors to pinpoint the primary areas where ChatGPT excels and where there is potential for enhancement, thereby augmenting its efficacy as a user-oriented tool. The outcomes of this research are anticipated to provide valuable insights into the optimization of ChatGPT and other AI-supported systems.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. User Information Satisfaction Factors

As previously mentioned, this study employs seven measures of User Information Satisfaction—completeness, accuracy, precision, reliability, timeliness, convenience, and format—to assess user satisfaction. These measures are intricately linked to the user context of ChatGPT, situating the research at the intersection of AI utility and user experience. The objective is to conduct a comprehensive examination of how each of these UIS dimensions contributes to overall user satisfaction when interacting with ChatGPT. This methodological approach facilitates a detailed exploration of the system’s effectiveness and the user experience it fosters, offering insights that can guide future refinements and modifications to optimize ChatGPT for its users.

In the realm of ChatGPT’s responses, ‘completeness’ refers to the depth and breadth with which user inquiries are addressed. Studies, such as those by Gupta et al. (2020), indicate that users value detailed and comprehensive answers, as they contribute to a fuller understanding of the subject matter. A ChatGPT system that responds to complex user questions with complete, adequate, and specific information demonstrates a more thorough comprehension (Cheung & Lee, 2009). Particularly noteworthy is ChatGPT’s ability to identify and comprehend the implicit questions posed by users, generating responses that are both comprehensive and relevant. Additionally, ChatGPT’s capacity to present updated and current knowledge stands out as an added value. This correlation suggests that the more complete the responses provided by ChatGPT, the higher the likelihood of user satisfaction, underscoring the significance of depth and breadth in the delivery of information. Therefore, it is posited that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) . The more complete the information provided by ChatGPT, the higher the user satisfaction.

In this study, accuracy is conceptualized as the truthfulness and correctness of ChatGPT’s responses. Personalized information, when provided in ample and relevant quantities, is typically perceived as delivering accurate information recommendations to users (Kim et al., 2023). This perspective is informed by the accuracy of textual outputs such as language modeling, text categorization, or the question-and-answer formats generated by ChatGPT (Saka et al., 2023). ChatGPT’s capability to comprehend and interpret complex queries to produce answers reflecting the veracity of information contributes to user satisfaction (Raj et al., 2023). Prior research emphasizes the criticality of accurate information for users, especially in decision-making contexts (Foroughi et al., 2023). This study posits a direct positive relationship between the accuracy of provided information and user satisfaction levels, highlighting the importance of delivering truthful and reliable answers to enhance the user experience. Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2) . The higher information accuracy from ChatGPT is associated with higher user satisfaction.

Precision in ChatGPT’s responses, which focuses on the relevance and specificity of user queries, is crucial. Research indicates that users favor targeted answers that directly address their specific issues (Reinecke & Bernstein, 2013). These responses provide information that aligns closely with the user’s needs, offering specific solutions to their presented problems. Consequently, users perceive that the ChatGPT system understands their requirements through precise and thorough responses that meet or even exceed their expectations (Roumeliotis et al., 2024). This suggests that the more precise the information provided, the greater the user satisfaction, underscoring the importance of contextually specific and tailored responses. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3) The more precise information from ChatGPT the higher user’s satisfaction.

Reliability refers to the consistency and dependability of ChatGPT’s responses over time. The quantity of information considered reliable pertains to responses that not only address the immediate informational needs of users but also provide them with opportunities for deeper knowledge acquisition (Wong et al., 2023). Users who perceive ChatGPT as a reliable source, offering consistent and dependable responses, are likely to experience higher satisfaction levels. User interaction studies have shown that consistent performance fosters user trust and satisfaction (Chen et al., 2021). This highlights the importance of ChatGPT maintaining stable and reliable outputs to sustain user satisfaction. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The more reliable information from ChatGPT the higher user’s satisfaction.

Timeliness in the context of ChatGPT’s responses emphasizes the speed at which it delivers information. ChatGPT’s ability to provide instant and prompt responses is instrumental in enhancing interaction efficiency and fulfilling user expectations (Niu & Mvondo, 2024). When users pose questions and receive accurate responses from ChatGPT promptly, it aids them in resolving their issues more effectively. Additionally, the responsive nature of the ChatGPT system facilitates interactions that lead users to rely on it (Akiba & Fraboni, 2023), casting a positive light on the quality and responsiveness of ChatGPT’s performance. Rapid and accurate replies are posited to increase user satisfaction (Petter & Fruhling, 2011). In the realm of digital communication, timeliness is highly valued. Users often equate quick responses with efficiency and effective service, thereby enhancing their overall satisfaction with the tool.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). The higher timeliness from ChatGPT will increase user’s satisfaction.

Convenience in the utilization of ChatGPT encompasses factors such as ease of use and accessibility. The system’s ability to comprehend commands or queries translates into user-friendly experiences (Saif et al., 2024). A simplistic design that facilitates user-system communication fosters a more comfortable interaction experience. Moreover, the provision of clear and timely responses helps users avoid confusion and feel more in command of the interaction. High levels of convenience generate positive user experiences and lead to greater satisfaction. This study posits that convenience plays a crucial role in user satisfaction. Human-computer interaction research indicates that tools that are easy to use and accessible significantly enhance user experience and satisfaction. This implies that the more user-friendly and accessible ChatGPT is, the higher the user satisfaction. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 6 (H6) . The higher convenience generating information with ChatGPT will significantly boosts user satisfaction.

The formatting of information delivered by ChatGPT, including its clarity, organization, and presentation, is posited to influence user satisfaction. Responses that are well-structured, employing clear paragraphing, bullet points, and other visual aids, facilitate users’ ability to quickly locate and comprehend information (Jin & Kim, 2023). Information that is neatly organized acts as a guide for users to grasp the context and inspect specific sections of the response in detail. Research suggests that well-structured information, presented in a clear and coherent manner, enhances user understanding and satisfaction (Park et al., 2011). The correlation here is that user-friendly and well-organized response formats are likely to positively impact user satisfaction levels, as they enable easier comprehension and interaction. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7 (H7) . The easier to understand the information format from ChatGPT will positively impacts user satisfaction.

4. Methods

4.1. Measures

This study adopts the UIS concept developed by Ives et al. (1983) as the foundational framework for developing its conceptual research structure. However, for the seven UIS measures, this research draws on previous studies, making modifications and adjustments specific to this study’s context. This approach is necessitated by the absence of measures directly evaluating the UIS of ChatGPT from previous studies. Consequently, the study employs 21 questions across four satisfaction dimensions, modified from Bhattacherjee (2001). For completeness, timeliness, and format, six items are adapted and refined from Laumer et al. (2017). Accuracy is adapted from Foroughi et al. (2023) to include three items. Precision, reliability, and convenience are modified from Ives et al. (1983), resulting in eight items. This methodical adaptation ensures the measures are suitably aligned with the unique characteristics and user interactions of ChatGPT, providing a robust and relevant evaluation of user satisfaction. Through this comprehensive approach, the study aims to offer a detailed and broader understanding of user satisfaction with ChatGPT, contributing significantly to the field of user experience research in AI-powered systems.

Table 1 present the measurement items that used to this study.

4.2. Sampling Technique and Data Collection Procedures

This study adopts a quantitative methodology, utilizing a survey designed to reach specific research participants. The data is gathered through an online survey, based on a meticulously crafted questionnaire. This questionnaire comprises three distinct parts. Initially, it requests the consent of the participants, aligning with the study’s use of purposive sampling. To be eligible, respondents must meet two key criteria: a) they should have used ChatGPT for over six months for academic purposes, and b) they should have a background in higher education, including roles like faculty members, students (both graduate and undergraduate), or postdoctoral researchers. This ensures the study targets the relevant population. The second section of the questionnaire collects sociodemographic data, such as gender, age, type of university, and occupation. Finally, the third section invites respondents to answer the specific questions developed for this research. This systematic approach facilitates the collection of comprehensive and pertinent data, thus guaranteeing that the study’s findings are insightful and accurately represent the experiences of ChatGPT users in academic environments. The design of this methodology is crucial in understanding the diverse ways in which different demographic groups use and perceive ChatGPT, greatly enhancing the depth and breadth of the research outcomes.

Over a three-month data collection period from August to November 2023, this study successfully gathered 508 responses. Within the collected data, males comprised 73% of the users. In terms of age demographics, the 21 to 35-year-old bracket was predominant in ChatGPT usage within the higher education landscape, accounting for 75% of respondents. Regarding the type of university, the distribution appears to be 57% from public universities, with the remaining 43% coming from private institutions. In examining the occupational demographics, undergraduate students constituted 39% of participants, graduate students (both master’s and doctoral candidates) made up 32%, faculty members represented 15%, and the remainder at 14% consisted of postdoctoral researchers.

4.3. Data Analysis Technique

This research involves several stages of data analysis. Initially, to ensure the validity and reliability of the instruments, the study conducts a Common Method Variance test. This assesses the consistency and validity of the instruments used in the research, employing Harman’s Single Factor method tested through SPSS version 26 (Baumgartner et al., 2021). Secondly, the study applies validity, reliability, and hypothesis analyses using the Structural Equation Modeling approach with Smart-PLS 4.0 software. This phase includes testing convergent validity to assess Outer Loadings (OL), Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (Hair et al., 2017). Furthermore, the research model evaluation involves testing discriminant validity through Fornell-Larcker Criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio/HTMT (Henseller et al., 2015), and Cross-Loadings Matrix (Hair et al., 2017), along with R-square (Falk & Miller, 1992) and goodness of fit evaluation (Hair et al., 2017). By these comprehensive methods, the study seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of how each UIS factor contributes to user satisfaction, thereby offering valuable insights into user experience with ChatGPT.

5. Discussion

5.1. Common Method Variance

Before proceeding with further data analysis, a Common Method Variance (CMV) test is conducted. The method employed is Harman’s Single Factor, where all measures are factored into a single dependent variable. If the total variance explained is below 50%, CMV is not considered a concern (Baumgartner et al., 2021). Utilizing SPSS for the CMV test, a result of 13.6% was obtained, which is well below the 50% threshold. Consequently, it is concluded that CMV does not pose a concern in this study. This finding establishes a strong foundation for the credibility of the subsequent analysis, ensuring that the data interpretation and results are robust and reliable. The low CMV percentage enhances the validity of the study, reinforcing the integrity of the research findings and their implications.

5.2. Validity and Reliability Assessment

Table 2 displays the results for convergent validity and reliability. The findings indicate that all statistical criteria suggested by Hair et al. (2017), including Outer Loadings OL, CA, CR, VIF, and AVE, have been met. Consequently, it can be concluded that convergent validity and reliability are not concerns in this study.

Subsequent testing focused on assessing discriminant validity to evaluate the efficacy of the model developed in this study. Three methods were employed for this purpose, as illustrated in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 3 indicates that the discriminant validity testing, using the Fornell-Larcker Criterion and the HTMT method, shows that 1) all diagonal and bolded values are greater than the intervariable correlation values. This suggests no concerns regarding discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2017). Additionally, the HTMT values obtained are all below the threshold of 0.90, leading to the conclusion that discriminant validity is not a concern. These results confirm the distinctiveness of the constructs within the model, ensuring that each measure captures a unique aspect of the phenomenon under study, which is crucial for the overall validity of the research findings.

Next, the discriminant validity was tested using the Cross-Loading Matrix method, as presented in

Table 4. The results indicate that the correlation of each construct with its respective measurement items is greater than with cross items. This finding suggests that discriminant validity is not a concern in this study. The clear differentiation of the constructs further strengthens the reliability and accuracy of the measurement model, ensuring that each construct is distinctively and accurately captured within the research framework (Hair et al., 2017).

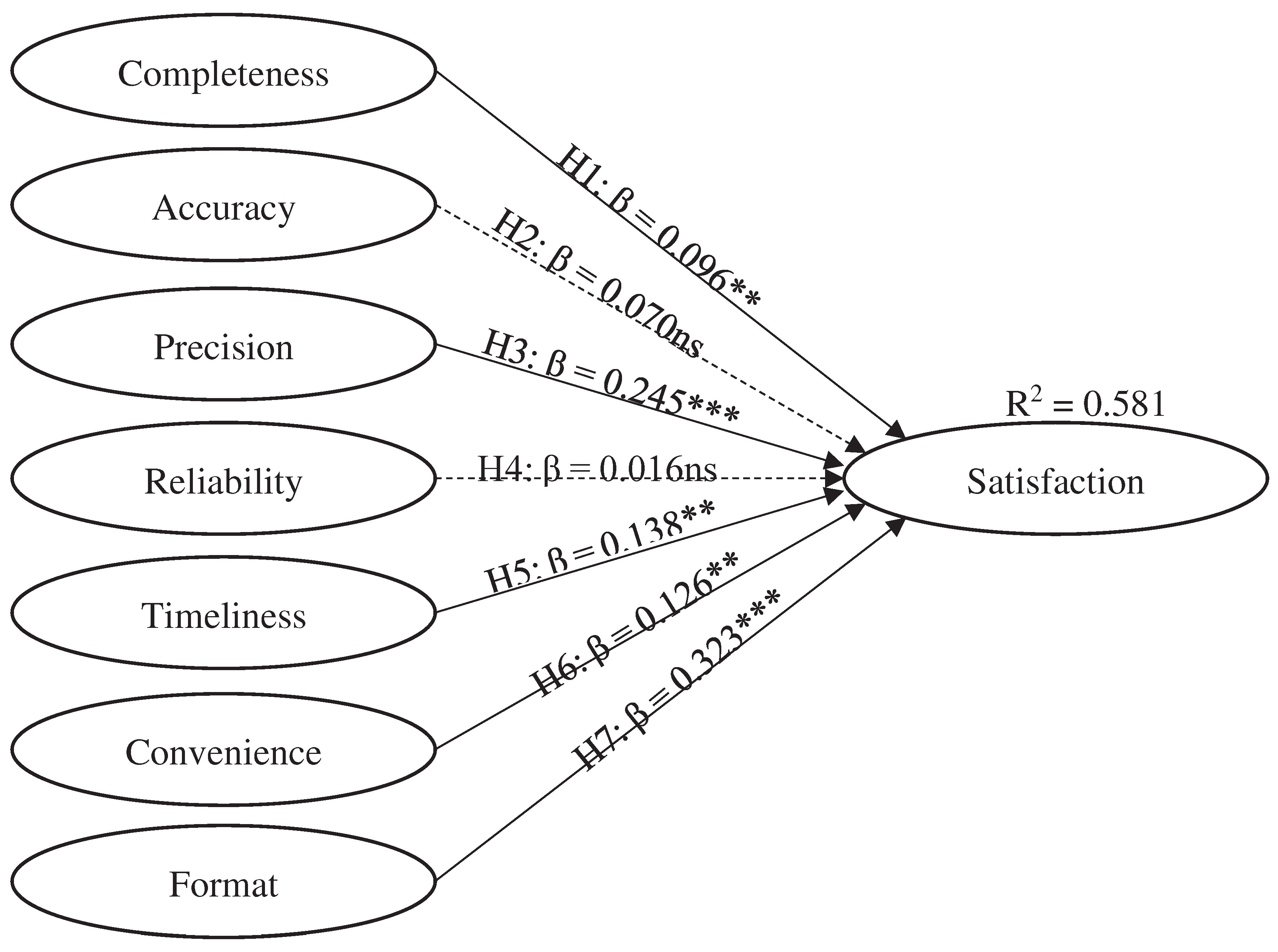

The model testing then proceeded with an evaluation of model fit and R-Square. The results indicated an SRMR value of 0.070, a Chi-Square of 1631.471, and an NFI of 0.783, all of which fall within the threshold limits recommended by Hair et al. (2017). Subsequently, the R-square value was assessed to determine the power of independent constructs in predicting the dependent constructs. An R-square value of 0.581 was obtained, indicating that the seven ChatGPT UIS measures can account for 58.1% of the variance in satisfaction. This meets the criteria set by Falk & Miller (1992), as the R-square value is above the 0.10 benchmark. These findings not only demonstrate the model’s good fit but also underline the considerable explanatory power of the identified factors in understanding user satisfaction with ChatGPT.

In this study, the Goodness of Fit (GOF) metric was calculated to evaluate the reliability of the constructed model. The GOF is determined by taking the square root of the product of the average variance extracted (AVE) and the average R squared (R^2), as indicated in Equation 1. Tenenhaus et al. (2005) and Wetzels et al. (2009) suggest that a GOF value above 0.36 indicates a high fit, between 0.25 and 0.36 signals a moderate fit, and between 0.10 and 0.25 points to a low fit. The computed GOF for this study is 0.635, which exceeds the threshold for a high fit, demonstrating the robustness and reliability of the model.

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

Table 5 and

Figure 2 provides a summary of the hypothesis testing. The analysis revealed that two UIS measures, accuracy (β = 0.070; T = 1.247) and reliability (β = 0.016; T = 0.400), were not significant predictors of satisfaction, leading to the rejection of hypotheses H2 and H4. On the other hand, it was found that completeness (β = 0.096; T = 2.863), convenience (β = 0.126; T = 2.192), format (β = 0.323; T = 5.115), precision (β = 0.245; T = 3.681), and timeliness (β = 0.138; T = 2.396) had a significant impact on satisfaction, supporting hypotheses H1, H3, H5, H6, and H7. However, a closer examination indicates that format and precision have a more substantial impact on satisfaction compared to the others. These results highlight the varying degrees of influence that different UIS measures have on user satisfaction, with some factors playing a more critical role than others in shaping user experiences with ChatGPT.

6. Discussion and Implication

6.1. Main Findings

This research represents a groundbreaking effort to apply the User Information Satisfaction (UIS) framework to the realm of generative AI, particularly ChatGPT, distinguishing itself as the first of its kind in the literature. Moving beyond the traditional UIS constructs championed by Ives et al. (1983), which prioritize accuracy and reliability, our study sheds light on a shift in user satisfaction determinants. We found that factors such as completeness, convenience, format, precision, and timeliness are more indicative of user satisfaction in the context of ChatGPT, signaling a change in user preferences that aligns with the evolution of AI technology. Moreover, the specific aspects of user satisfaction with ChatGPT seem to mirror the broader technological landscape’s tendencies, resonating with Pan et al.’s (2023) discovery of the varied uncertainties users face when interacting with AI-driven social chatbots. Our findings underscore a clear valuation of ChatGPT’s ability to deliver clear and timely information, which aligns with the dynamic and context-sensitive nature of user engagement with technology found in contemporary research.

This research indicates a paradigm shift in the UIS framework, particularly within the context of advanced generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT. According to the study, traditional UIS measures that prioritize accuracy and reliability may not sufficiently address broader of user satisfaction in AI interactions (Ameen et al., 2021; Ma & Huo, 2023; Bubaš et al., 2023). This evolving landscape suggests a need for an updated UIS framework that includes the various nature of user information satisfaction, reflecting the importance of how information is conveyed and its integration into user workflows (Brill et al., 2022; ). As users become increasingly proficient with AI, their satisfaction criteria evolve, demanding a more sophisticated approach to system design—one that goes beyond functional correctness to consider the overall user experience.

Furthermore, our findings serve as a catalyst for future research aimed at redefining UIS metrics to better suit the context of AI. We propose that system designers should focus on enhancing qualitative aspects such as the completeness, convenience, format, precision, and timeliness of information provided by AI systems (Lee & Kim, 2022). These factors are becoming pivotal in determining user satisfaction and, therefore, should be integral to the design process. Echoing the discoveries by Pan et al. (2023), who explored the varied uncertainties users face with AI chatbots, our study underscores the significance of adapting the UIS framework to address these emergent user satisfaction determinants. Such an adaptation will be crucial in developing AI systems that not only meet the functional expectations of users but also enrich their overall interaction with the technology, ensuring that advancements in AI are paralleled by improvements in user value.

6.2. Implication for Theory

This research marks a significant advancement in the theoretical framework of UIS, scrutinizing the traditionally emphasized roles of accuracy and reliability that Ives et al. (1983) posited as central to user satisfaction. By exploring the use of ChatGPT, findings indicate that these long-valued factors may not hold as much influence over user satisfaction in the rapidly evolving landscape of generative AI technology. This pivotal study suggests that the UIS paradigm is undergoing a transformation, prompting a reevaluation of what constitutes user satisfaction. The investigation reveals that users of AI interfaces might place greater importance on how information is provided to them, rather than just its correctness or dependability. Aspects such as how complete the information is, how user-friendly the format is, how precisely it meets the user’s needs, and how quickly it is delivered, have emerged as critical to satisfaction.

Building on these insights, the study broadens the narrative of UIS by incorporating additional determinants that resonate with the digital era’s user interaction dynamics. In doing so, it echoes and expands upon the research by Laumer et al. (2010), who also recognized the need to adapt UIS measures to reflect modern digital interaction patterns. The research delineates a more nuanced comprehension of user satisfaction, one that encapsulates the diverse priorities of users as they engage with sophisticated AI technologies. The inclusion of completeness, convenience, format, precision, and timeliness in the UIS framework represents a shift towards a more holistic approach to understanding user satisfaction, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of user experience in the context of contemporary information systems. This enhancement of the UIS framework is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications for the design and development of user-centric AI systems that can meet and exceed the evolving expectations of users in an increasingly digital world.

6.3. Implication for Practice

This research provides a nuanced analysis of ChatGPT’s application, significantly enriching the discourse on how organizations can optimize the use of generative AI. It challenges the longstanding precept that the primary focus should be on the accuracy and reliability of information systems, a principle traditionally held by scholars like Ives et al. (1983). Instead, our findings suggest organizations should pivot toward aspects such as completeness, convenience, format, precision, and timeliness (Laumer et al., 2017). Such a recalibration can lead to more user-centric interfaces, potentially increasing engagement and satisfaction with AI tools, which in turn may enhance organizational efficiency and improve the return on investment in AI technologies (Fraisse & Laporte, 2022).

At the organizational level, the implications of this study are profound. Entities that prioritize these newly identified factors in their AI systems can expect to develop interfaces that resonate more effectively with their users’ needs. By creating systems that users find more intuitive and efficient, organizations stand to benefit from higher levels of user interaction and satisfaction, which can translate into increased productivity and better utilization of AI technologies (Williams et al., 2023). These outcomes underscore the importance of aligning system design with evolving user expectations, as highlighted by the progressive nature of user engagement in the digital realm (Anderson et al., 2018).

For individuals, especially those frequently interacting with AI technologies like ChatGPT, the study underscores the importance of becoming proficient in features that enhance the utility of these systems. User education should shift focus towards empowering individuals to effectively engage with and extract value from AI. As users become more skilled in leveraging the streamlined functionalities of these systems, they can bolster their efficiency and productivity, which are essential in a rapidly digitizing world (Lu, 2019). This education is not just about functionality but also about setting appropriate expectations and maximizing the benefits of AI in diverse contexts like work and learning (Davis, 2017).

Finally, by equipping users with the knowledge to fully utilize AI tools, this study reinforces the importance of user competency in the digital age. Individuals who understand and utilize the advanced features of systems like ChatGPT can enhance their own technological literacy and efficacy. This empowerment is critical as it allows users to harness the full potential of AI in their professional and educational pursuits, establishing them as savvy operators within an increasingly complex technological ecosystem (Martin & Ertzberger, 2016). This user-centric approach to AI utilization not only benefits the individual but also contributes to the broader goal of integrating these advanced tools into society in a manner that maximizes their utility and facilitates growth and innovation.

7. Conclusions and Limitation

As this study draws to a close, it becomes clear that the User Information Satisfaction framework requires reexamination in the era of generative AI, notably in the application of ChatGPT. Challenging the previously accepted belief that accuracy and reliability are the paramount indicators of user satisfaction, our research proposes that these standards are evolving alongside AI advancements. The rise of factors such as completeness, convenience, format, precision, and timeliness as critical to user satisfaction signifies a dramatic transition in the way users interact with AI interfaces. Consequently, this necessitates the reformation of the UIS framework to better encapsulate and respond to these emerging user preferences. Our study sets a precedent for future inquiry, highlighting the imperative to align AI system design with the intricate and evolving demands of users, focusing on a design philosophy that places immediate utility and seamless interaction at the forefront.

This research also has wide-ranging practical applications, influencing both how organizations and individuals use AI technologies such as ChatGPT. It prompts organizations to adjust their AI systems to emphasize the satisfaction factors our study has pinpointed, which can lead to heightened user engagement and a more substantial return on AI investments. On a personal level, the findings accentuate the value of becoming adept with AI tools to boost efficiency and output. Users who refine their skills with AI features that dovetail with their routine responsibilities can fully leverage the advantages these technological innovations offer. Together, the insights from this study call for an anticipatory and strategic embrace of AI across diverse domains, aiming to align tech progress with a comprehensive grasp of user satisfaction, thereby unlocking the complete potential of AI within the dynamic environment of digital existence.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations that open avenues for future research. The investigation was constrained by its focus on ChatGPT, which, while representative of generative AI, may not condense the full spectrum of user interactions across different AI platforms. Furthermore, the study’s reliance on self-reported measures of satisfaction could introduce response biases that might not fully capture the nuanced reactions users have towards AI interfaces. Subsequent studies could expand the research to include a broader range of AI tools and technologies, thereby enriching the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, incorporating objective usage data could provide a more comprehensive understanding of user satisfaction and behavior, offering a more holistic view of how individuals and organizations interact with AI systems. Future research could also explore longitudinal studies to assess how satisfaction with AI evolves over time as users become more accustomed to these technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.F.; I.T.S. and A.D.K.S.; methodology, A.D.K.S. and I.J.E.; software, A.D.K.S.; validation, S.J., and D.T.T.P..; formal analysis, A.D.K.S.; investigation, A.D.K.S. and D.T.T.P.; resources, C.J.F. and I.T.S.; data curation, A.D.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.K.S.; I.T.S.; D.T.T.P. and I.J.E.; writing—review and editing, C.J.F.; S.J. and I.J.E.; visualization, I.J.E.; supervision, C.J.F.; project administration, A.D.K.S.; funding acquisition, C.J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akiba, D.; Fraboni, M.C. AI-supported academic advising: Exploring ChatGPT’s current state and future potential toward student empowerment. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, N.; Tarhini, A.; Reppel, A.; Anand, A. Customer experiences in the age of artificial intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 114, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Rainie, L.; Luchsinger, A. Artificial intelligence and the future of humans. Pew Research Center 2018, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, A.N.; Ahmad, S.; Bhutta, S.M. Mapping the global evidence around the use of ChatGPT in higher education: A systematic scoping review. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, M. Is ChatGPT scary good? How user motivations affect creepiness and trust in generative artificial intelligence. Telematics and Informatics 2023, 83, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Law, R.; Wen, I. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. International journal of hospitality management 2008, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Weijters, B.; Pieters, R. The biasing effect of common method variance: Some clarifications. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2021, 49, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS quarterly 2001, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Sadallah, M.; Bouteraa, M. Use of ChatGPT in academia: Academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technology in Society 2023, 75, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, T.M.; Munoz, L.; Miller, R.J. 2022. Siri, Alexa, and other digital assistants: a study of customer satisfaction with artificial intelligence applications. In The Role of Smart Technologies in Decision Making (pp. 35-70). Routledge.

- Bringula, R. What do academics have to say about ChatGPT? A text mining analytics on the discussions regarding ChatGPT on research writing. AI and Ethics 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubaš, G.; Čižmešija, A.; Kovačić, A. Development of an Assessment Scale for Measurement of Usability and User Experience Characteristics of Bing Chat Conversational AI. Future Internet 2023, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zahedi, F.M.; Abbasi, A.; Dobolyi, D. Trust calibration of automated security IT artifacts: A multi-domain study of phishing-website detection tools. Information & Management 2021, 58, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. User satisfaction with an internet-based portal: An asymmetric and nonlinear approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2009, 60, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.C. Internet connection: AI and libraries: Supporting machine learning work. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian 2017, 36, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, L.; Baglivo, F.; Arzilli, G.; Privitera, G.P.; Ferragina, P.; Tozzi, A.E.; Rizzo, C. ChatGPT and the rise of large language models: the new AI-driven infodemic threat in public health. Frontiers in Public Health, 2023, 11, 1166120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, G.; Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Azara, A.; Gabutti, G.; Castiglia, P. Artificial intelligence and public health: evaluating ChatGPT responses to vaccination myths and misconceptions. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Wright, R. “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essel, H.B.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Tachie-Menson, A.; Johnson, E.E.; Baah, P.K. The impact of a virtual teaching assistant (chatbot) on students’ learning in Ghanaian higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 2022, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R. F.; Miller, N. B. 1992. A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, H.; Laporte, M. Return on investment on artificial intelligence: The case of bank capital requirement. Journal of Banking & Finance 2022, 138, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fui-Hoon Nah, F.; Zheng, R.; Cai, J.; Siau, K.; Chen, L. Generative AI and ChatGPT: Applications, challenges, and AI-human collaboration. Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research 2023, 25, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, D.F.; Lederer, A.L. Some cautions on the measurement of user information satisfaction. Decision Sciences 1989, 20, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Motlagh, M.; Rhyner, J. The digitalization sustainability matrix: A participatory research tool for investigating digitainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial management & data systems, 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, B.; Olson, M.H.; Baroudi, J.J. The measurement of user information satisfaction. Communications of the ACM 1983, 26, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Kim, M. GPT-Empowered Personalized eLearning System for Programming Languages. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, C.; Park, J. Decisions with ChatGPT: Reexamining choice overload in ChatGPT recommendations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2023, 75, 103494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocoń, J.; Cichecki, I.; Kaszyca, O.; Kochanek, M.; Szydło, D.; Baran, J.; Kazienko, P. ChatGPT: Jack of all trades, master of none. Information Fusion 2023, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumer, S.; Maier, C.; Weitzel, T. Information quality, user satisfaction, and the manifestation of workarounds: a qualitative and quantitative study of enterprise content management system users. European Journal of Information Systems 2017, 26, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ren, Y.; Nyagoga, L.M.; Stonier, F.; Wu, Z.; Yu, L. Future of education in the era of generative artificial intelligence: Consensus among Chinese scholars on applications of ChatGPT in schools. Future in Educational Research 2023, 1, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K. What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Education Sciences, 2023, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Artificial intelligence: a survey on evolution, models, applications and future trends. Journal of Management Analytics 2019, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B.D.; Wang, T.; Mannuru, N.R.; Nie, B.; Shimray, S.; Wang, Z. ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligence-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2023, 74, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huo, Y. Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technology in Society 2023, 75, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Ertzberger, J. Effects of reflection type in the here and now mobile learning environment. British Journal of Educational Technology 2016, 47, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D.; Shilpa, K. “Chatting with ChatGPT”: Analyzing the factors influencing users’ intention to Use the Open AI’s ChatGPT using the UTAUT model. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meron, Y.; Araci, Y.T. Artificial intelligence in design education: evaluating ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for post-graduate course development. Design Science 2023, 9, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Mvondo, G.F.N. I Am ChatGPT, the ultimate AI Chatbot! Investigating the determinants of users’ loyalty and ethical usage concerns of ChatGPT. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2024, 76, 103562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Cui, J.; Mou, Y. Desirable or Distasteful? Exploring Uncertainty in Human-Chatbot Relationships. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P.; Lim, G.G. Examining success factors in the adoption of digital object identifier systems. Electronic commerce research and applications 2011, 10, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; Fruhling, A. Evaluating the success of an emergency response medical information system. International journal of medical informatics 2011, 80, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, V.; Verma, P. Analyzing the potential benefits and use cases of ChatGPT as a tool for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of business operations. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2023, 3, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, K.; Bernstein, A. Knowing what a user likes: A design science approach to interfaces that automatically adapt to culture. Mis Quarterly 2013, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, P.; Zhao, L. Marketing with chatgpt: Navigating the ethical terrain of gpt-based chatbot technology. AI 2023, 4, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D.; Nasiopoulos, D.K. LLMs in e-commerce: A comparative analysis of GPT and LLaMA models in product review evaluation. Natural Language Processing Journal 2024, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose. 2023. Don’t Ban ChatGPT in Schools. Teach With It. Retreived from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/technology/chatgpt-schools-teachers.html.

- Saif, N.; Khan, S.U.; Shaheen, I.; ALotaibi, A.; Alnfiai, M.M.; Arif, M. Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Computers in Human Behavior 2024, 154, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, A.; Taiwo, R.; Saka, N.; Salami, B.A.; Ajayi, S.; Akande, K.; Kazemi, H. GPT models in construction industry: Opportunities, limitations, and a use case validation. Developments in the Built Environment 2023, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Computational statistics & data analysis 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS quarterly 2009, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Berman, G.; Michalska, S. Investigating hybridity in artificial intelligence research. Big Data & Society 2023, 10, 20539517231180577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Lian, Q.L.; Sun, D. Autonomous travel decision-making: An early glimpse into ChatGPT and generative AI. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 56, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).