Submitted:

29 January 2024

Posted:

01 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Participants and sampling

2.3. Data collection

2.3.1. High Fidelity Simulation Procedure

2.4. Data analysis

2.5. Ethical considerations

2.6. Strictness criteria

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

3.2. Themes

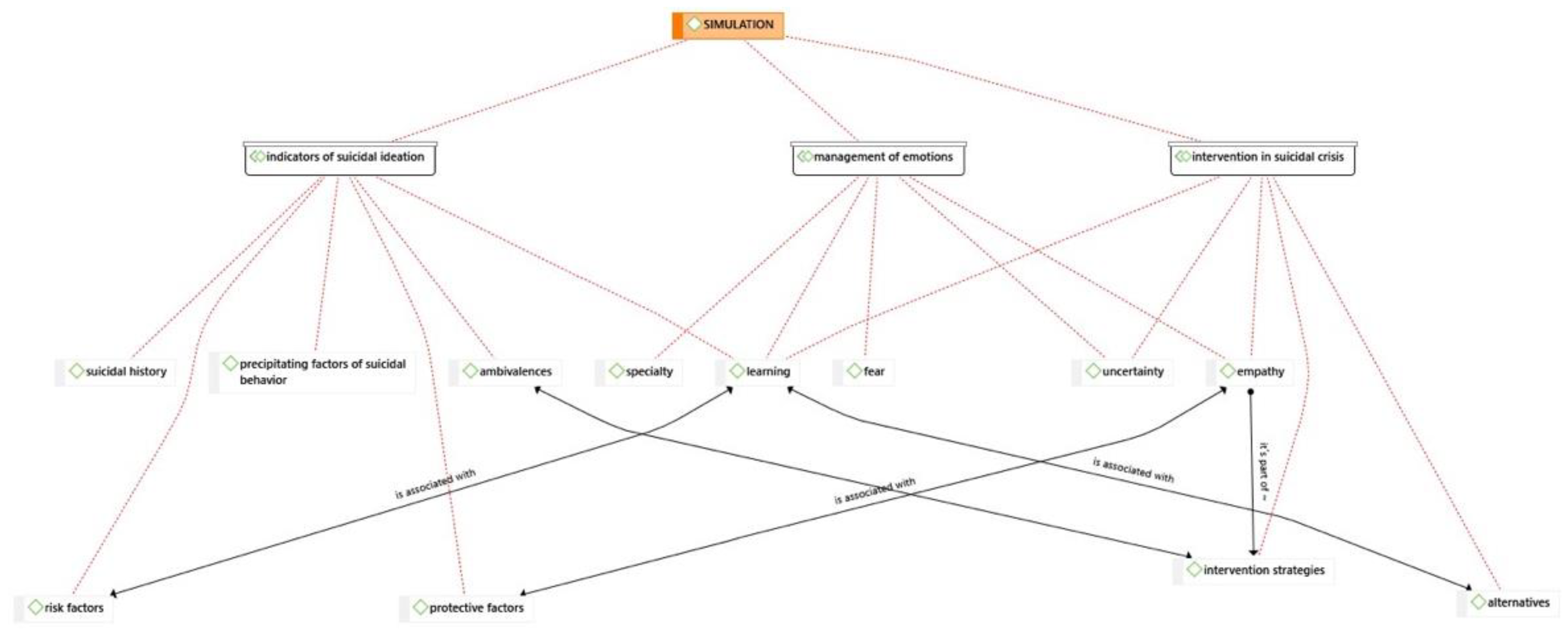

| Themes (T) | Categories | |

|---|---|---|

| T 1 | Management and handling of emotions | Fear, uncertainty, empathy, trust, learning, specialty. |

| T 2 | Indicators of suicidal behavior | Risk factors and protective factors, precipitating factors of suicidal behavior, suicidal history, ambivalence. |

| T 3 | Suicidal crisis intervention | Establishment of the relationship, intervention strategies and alternatives. |

- Theme 1: Management and handling of emotions.

“The uncertainty, isn’t it? Because in the end the situation doesn’t depend on you...”GF3

“I don’t know... as if he was always telling bad things, you empathized a lot with him... and you said fuck... and you wanted to find something good for him to get out of that... out of that loop from which he wants to commit suicide... I don’t know...” GF2 “I have felt the desperation that they suffer, the inability to cope with situations”GF1

“My fear of these situations has been removed and I find myself much more prepared” E15 “I gained confidence by remembering the points explained earlier”E4

“I have been very motivated thinking about the possibility of doing the mental health specialty” E27 “I thought I didn’t like mental health, but since the simulation it has caught my attention and I am really looking forward to it”E31

“It has been challenging, helping us to reflect and having a link between theory and practice.”E20

“I have been able to learn the keys to interventions for these patients.”E22

“It has been fundamental to have a real actor as a patient, it has made the simulation much more realistic” .(E19).

- Theme 2: Indicators of suicidal behavior.

“The economic issue, the family issue, the divorce issue, the relationship with the daughters, all these are risk factors”GF1.

“...it is an indicator, it is a protective factor the issue of beliefs”GF4.

“The suicidal career can be very varied, but such events accumulate that I accumulate and there comes a time when I can’t take it anymore and that drop is predisposed”GF3.

“The wife... the daughters... have been a bit ambivalent, right? At the beginning it seemed like... then it seemed like... with you it seemed like”(GF1). 354

“Creating ambivalence yes it can be all and I at the end for them to decide and make that decision to take another path”GF2,

“Once the life hitch was identified, it has been easier to establish ambivalence”E9. 360

- Theme 3: Suicide crisis intervention.

“We have learned how the approach to the simulation should be, following the steps”(E12).

“The connection, what’s the first thing to do? Hook up with the person, otherwise you’re not going to have anything”GF4.

“I introduced myself, tried to get him to talk to me and got down to his level”GF2.

“I position myself as a safety measure to ensure that the person does not catch me at a given moment and throw me away, but I put myself at his or her level.

“My partners and I did a pretty thorough approach...using relaxation techniques...looking for alternatives”E4.

“Sometimes I’ve felt like it was like what the two partners said a little bit, you’re left kind of thinking I don’t know if what I’m going to say now is going to be impactful enough for me to pay attention”GF2.

“I think the main thing is to accompany them, listen to them and make them feel supported...give alternatives that we can give him because he himself is not seeing them”E5.

“I told him that there were other alternatives to quitting that, even though he tried it once, it doesn’t mean it’s the only one, that he can try again”(GF3). 410

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and limitations of the study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide mortality data. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- Sufrate-Sorzano, T. Suicide prevention from the classroom. Nursing interventions and tools for suicide prevention: Activity book. Siníndice. 2021. Spain.

- Harmer, B.; Lee, S.; Duong, T.V.H.; Saadabadi, A. Suicidal Ideation. Stat Pearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024.

- Echávarri-Gorricho, A. Concept and classification of suicidal behavior. 2010. Available online: ftp.formainap.navarra.es/2014/2014-3E604-9971-SUICIDIO/TEMA%201.pdf.

- Hernández-Bello, L.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Cogollo-Milanés, Z. Prevalence and associated factor for ideation and suicide attempt in adolescents: A systematic review. Rev Esp Public Health. 2020, 10, 94. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. Deaths from causes, gender and age groups. 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=7947 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Spanish Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide Observatory in Spain. 2022 [online]. Available online: https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio-2022-definitivo/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Darnell, D.; Areán, P.A.; Dorsey, S.; Atkins, D.C.; Tanana, M.J.; Hirsch, T.; Mooney, S.D.; Boudreaux, E.D.; Comtois, K.A. Harnessing Innovative Technologies to Train Nurses in Suicide Safety Planning With Hospitalized Patients: Protocol for Formative and Pilot Feasibility Research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 72nd World Health Assembly. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_11Rev1-sp.pdf.

- Heyman, I.; Webster, B.J.; Tee, S. Curriculum development through understanding the student nurse experience of suicide intervention education--A phenomenographic study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015, 15, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motillon-Toudic, C.; Walter, M.; Séguin, M.; Carrier, J.D.; Berrouiguet, S.; Lemey, C. Social isolation and suicide risk: Literature review and perspectives. Eur. Psychiatry. 2022, 65, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oexle, N.; Rüsch, N. Stigma—Risk factor and consequence of suicidal behavior: Implications for suicide prevention. Nervenarzt. 2018, 89, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, V.; Vijayakumar, L. Interventions for attempted suicide. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2022, 1, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmani, A.; Rahimianbougar, M.; Mohammadi, Y.; Faramarzi, H.; Khodarahimi, S.; Nahaboo, S. Psychological, Structural, Social and Economic Determinants of Suicide Attempt: Risk Assessment and Decision Making Strategies. Omega. 2023, 86, 1144–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, M.; Butera, E.; Cerri, C.G.; Cornaggia, C.M.; Febbo, F.; Mollica, A.; Berardino, G.; Piscitelli, D.; Resta, E.; Logroscino, G.; Daniele, A.; et al. Suicidal behaviour in older age: A systematic review of risk factors associated to suicide attempts and completed suicides. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021, 127, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Terzoni, S.; Ruta, F.; Poggi, A.D.; Destrebecq, A.; Gambini, O.; D’agostino, A. Nursing students’ attitudes towards suicide and suicidal patients: A multicentre cross-sectional survey. Nurse Educ Today. 2022, 109, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Ramírez-Torres, C.A.; Rivera-Sanz, F.; Garrote-Camara, M.E.; Roland, P.P.; Gea-Sánchez, M.; Del Pozo-Herce, P.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Angulo-Nalda, B.; et al. Nursing interventions of choice for the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour: The umbrella review protocol. Nurs Open. 2022, 9, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.; Jollant, F.; Billon, G.; Attoe, C.; Vodovar, D.; Piot, M.A. Simulation training in suicide risk assessment and intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Educ. online. 2023, 28, 2199469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannoy, S.D.; Fancher, T.; Meltvedt, C.; Unützer, J.; Duberstein, P.; Kravitz, R.L. Suicide inquiry in primary care: Creating context, inquiring, and following up. Ann Fam Med. 2010, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawgood, J.; Woodward, A.; Quinnett, P.; De Leo, D. Gatekeeper Training and Minimum Standards of Competency. Crisis. 2022, 43, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.H.M.; Fuxman, S.; Humm, L.; Tirone, N.; Pires, W.J.; Cole, A.; Goldstein, G.J. Suicide risk assessment training using an online virtual patient simulation. mHealth. 2019, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.; Smith, A.R.; Dodd, D.R.; Covington, D.W.; Joiner, T.E. Suicide-Related Knowledge and Confidence Among Behavioral Health Care Staff in Seven States. Psychiatr Serv. 2016, 67, 1240–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, M.M.; Berman, A.L. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: A focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014, 44, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.S.; Selvarajan, S.; Chng, M.L.; Tan, C.S.; Yobas, P. Using standardized patients in enhancing undergraduate students’ learning experience in mental health nursing. Nurse Educ. today. 2016, 45, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.L.; Hermans, M.; Crawley, B. Psychiatric nursing emergency: A simulated experience of a wrist-cutting suicide attempt. J psychosoc nurs ment health serv. 2012, 50, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keltner, N.L.; Grant, J.S.; McLernon, D. Use of actors as standardized psychiatric patients. J psychosoc nurs ment health serv. 2011, 49, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot, M.A.; Attoe, C.; Billon, G.; Cross, S.; Rethans, J.J.; Falissard, B. Simulation Training in Psychiatry for Medical Education: A Review. Front. Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 658967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, A.K.; Hemani, A.; Fernandez, V.; Livingstone, D.; McCusker, K.; Toro-Troconis, M. Using virtual worlds for role 613 play simulation in child and adolescent psychiatry: An evaluation study. Psychiatr Bull. 2014, 38, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.H.M.; Quinlan, K.; Humm, L.; Cole, A.; Pires, W.J.; Jacobs, A.; Goldstein-Grumet, J. A qualitative study of 616 provider feedback on the feasibility and acceptability of virtual patient simulations for suicide prevention training. Mhealth. 617 2022, 30, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.C.; Neagle, G.; Cameron, B.; Moneypenny, M. It’s okay to talk: Suicide awareness simulation. Clin Teach. 2019, 16, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 2: Context, research questions and designs. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017, 23, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 2018.

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J gen Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 34. Nanda International, NANDA. Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2018–2020. Elsevier, 2019.

- Butcher, H.K.; Bulechek, G.M.; Dochterman, J.M.; Wagner, C.M. Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC); Elsevier. 2018. St. Louis, MO, USA.

- Sittner, B.J.; Aebersold, M.L.; Paige, J.B.; Graham, L.L.; Schram, A.P.; Decker, S.I.; Lioce, L. INACSL Standards of Best Practice for Simulation: Past, Present, and Future. Nur educ perspect. 2015, 36, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Raemer, D.B.; Simon, R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: The role of the presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc. 2014, 9, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, J.M.; Rudolph, J.W. Theories and styles of debriefing: The good judgment method as a tool for formative assessment in healthcare. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2015, 68, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkbakk-Fjær, K.; Hedelin, B.; Moen, Ø.L. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Evaluation of the Debriefing Phase in Mental Health Nursing Simulation. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Collins, J.C.; Roennfeldt, H.; McMillan, S.S.; Wheeler, A.J.; El-Den, S. Mental Health First Aid crisis 649 role-plays between pharmacists and simulated patients with lived experience: A thematic analysis of debriefing. Soc 650 Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qualitative Stud Health Well-being. 2014, 9, 26153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Critical Analysis of Strategies for Determining Rigor in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015, 25, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soccio, D.A. Effectiveness of Mental Health Simulation in Replacing Traditional Clinical Hours in Baccalaureate Nursing Education. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment Health Serv. 2017, 55, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGough, S.; Heslop, K. Developing Mental Health-Related Simulation Activities for an Australian Undergraduate Nursing Curriculum. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 60, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonelli-Muñoz, A.J.; Jiménez-Rodríguez, D.; Arrogante, O.; Plaza Del Pino, F.J.; Gallego-Gómez, J.I. Breaking the Stigma 668 in Mental Health Nursing through High-Fidelity Simulation Training. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1593–1606.669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.L.; Hermanns, M.; Crawley, B. Clinical Simulation in Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing: Post-Graduation Follow Up. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment Health Serv. 2016, 54, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Meier, S.; Fischer, C.; Brich, J. Simulated patients to demonstrate common stroke syndromes: Accurate and convincing. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, A.J.; Greco, L.; Airaldi, R.; Tulsky, J.A. Development of an Actor Rehearsal Guide for Communication Skills Courses. BMJ Palliat Care. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godzik, C.M.; Solomon, J.; Yacinthus, B. Using standardized mental health patient simulations to increase critical thinking and confidence in undergraduate nursing students. Arch. Psychiatr. 2023, 43, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, F.; Turgut, A.N.; Meriç, M. Nursing student’s attitudes toward death and stigma toward individuals who attempt suicide. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022, 58, 1728–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Post-Clinical simulation phase |

|

| Simulated Scenario 1 | NANDA | NIC Intervention |

NOC Outcomes |

Nursing Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34-year-old male, who on our arrival was on the M-40 bridge. He presented suicidal ideation and intention to jump. As background, he refers to an argument with his wife, he has two daughters that he has not seen for some time, cocaine consumption and his van broke down just today when he was going to deliver an order. There is no one else on the bridge, only you (nursing students). You are the first to intervene and establish the first contact with the person. |

(00150) Suicide risk |

(6486) Environmental management: Safety (4500) Prevention of substance abuse (6340) Suicide prevention |

(1408) Self-control of suicidal impulses (1904) Risk management: drug use |

|

| Simulated Scenario 2 |

NIC Intervention |

NOC Outcomes |

Nursing Activities | |

| Middle-aged man threatening to take his own life on the viaduct in Segovia (Madrid). No further information is available at the Emergency Service Center. You arrive as the first unit to intervene. When you arrive, the person is at high risk of suicide, as he is attached to a railing on the outside of the bridge. It is you (nursing students) who make the first contact. | (00124) Despair (00150) Suicide risk |

(5230) Increasing coping (5270) Emotional support (4920) Active Listening (6654) Surveillance: security |

(1302) Coping with problems (1305) Psychosocial modification: life change |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).