1. Introduction

Classical mechanics was developed in 1687 by Isaac Newton in his famous book

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica [

1]. In the subsequent 200 years, it was used to theoretically interpret all known physical phenomena. In 1900, a set of discoveries related to the nature of light, molecules, and atoms, led Max Planck to introduce a new way to describe the world: quantum mechanics (reviewed in [

2]). Subsequently, Erwin Schrödinger introduced in 1926 the wave nature of matter [

3], where a quantum wave function describes the state of a physical system following the famous Schrödinger equation

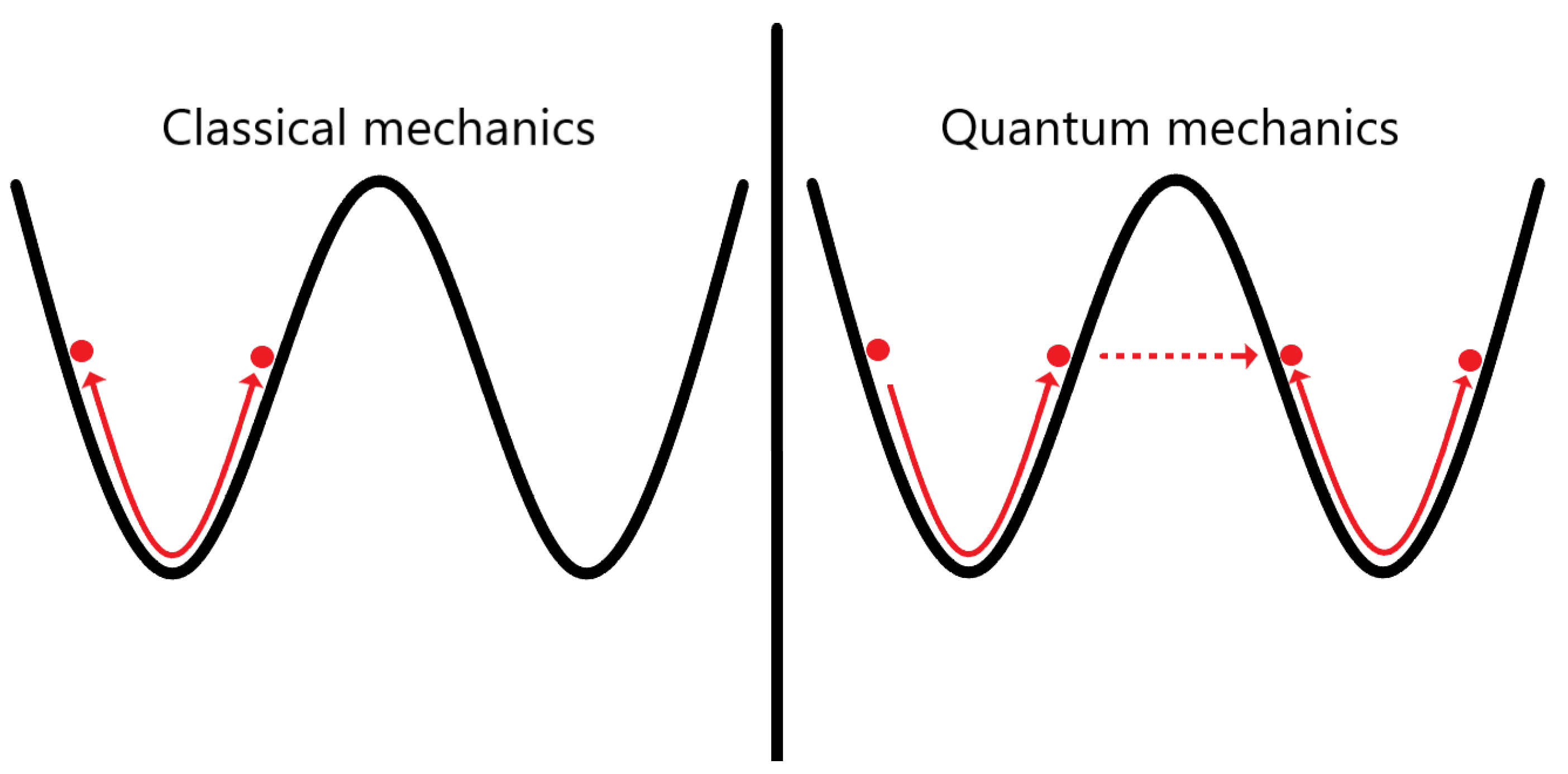

creating a probabilistic way to observe the world. This probabilistic treatment gave place to one of the less intuitive and most important discoveries of all time: quantum tunneling (reviewed in [

4]). Quantum tunneling is an effect where a particle can go through a potential barrier, in contrast with classical mechanics, where the particle must overcome this barrier possessing enough energy to do it. It can be seen graphically in

Figure 1.

In 1927, the German physicist Freidrich Hund [

5,

6], applied the Schrödinger equation (

1) to understand the behavior of chiral molecules, obtaining that the tunneling has consequences on it, as we will see later. The term “chiral” was first introduced by Lord Kelvin in 1901 [

7] to design all geometric structures or groups of points whose reflections in a plane mirror can not be superimposed with itself. He called the two possible forms of those geometric structures “enantiomers”. Later, it was discovered that the fundamental symmetry that interconverts the enantiomers is the parity symmetry (the symmetry through a point of inversion), not the reflection as Lord Kelvin stated [

8], acquiring parity processes great importance in the context of chiral molecules, specially the parity-violating ones, as we will see along the manuscript.

Parity-violating processes were derived from the prediction by Lee and Yang [

9], in which they postulated that parity can be violated in weak interactions, being the unique fundamental force capable of producing that behavior. That prediction was confirmed one year later by Wu et. al.[

10].

The fact that the weak force violates parity made physicists to ask at what scales parity-violating effects could be present. The first answer came from Bouchiat and Bouchiat [

11], by observing spontaneous optical activity of Bismuth atomic vapors, revealing effects of weak interactions in the atomic scale. After this important experiment was performed [

12], Wood and coworkers discovered the nuclear anapole moment of Cesium [

13], with is a different signal of parity violation, by improving low-temperature and high-resolution spectroscopic techniques. Therefore, parity violation was initially observed in elementary particles, and then in more complex systems like nuclei and atoms. If we continue considering more complex systems, we reach the molecular scale. Thus, one could ask if does it make sense to relate parity violation with molecular physics

As we have briefly commented in this introduction, there is an interesting interplay between chiral molecules, quantum tunneling and parity violation, which will be developed along the manuscript.

Specifically, this work is organized as follows: In

Section 2 we introduce a simple quantum treatment of chiral molecules and its relation with the tunneling time. In

Section 3 we add parity-violation to our description of chiral molecules, showing that there could exist an energy difference between the

L and

R enantiomers (PVED). In

Section 4 we give some examples of parity-violating interactions, focusing on the electroweak force. In

Section 5 we briefly review how the PVED can be calculated using simple or more sophisticated methods. In

Section 6 we mention some experiments devoted to detecting the PVED. Finally,

Section 7 provides the conclusions of the present work.

2. Introduction to molecular chirality

The process of converting an

L chiral molecule to its enantiomer,

R, can be represented by the movement of an effective mass in an energy potential

which is function of a generalized coordinate,

q [

14]. If we use the time-independent Schrödinger, we can obtain the eigenfunctions,

, and eigenvalues (energies),

, of the stationary states

where

is the kinetic energy, the potential energy is given by

, and

is the Hamiltonian operator.

In quantum mechanics, it is well known that the probability of the system to be in a determinate state can be expressed as

Interestingly, Hund applied the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (

1) to the study of chiral molecules, with emphasis on the stereomutation process between left and right states, which at this time was only thought to be a consequence of quantum tunneling. The time-dependent Schrödinger equation can be expressed as

and its general solution is

where

are complex coefficients.

As a first toy model, chiral molecules can be represented with only two states, related to the two possible chiralities, left-handed and right-handed. Taking into account these two lowest energy states, the solution of the Ec. (

5) is

where we denote as

and

the time-independent Hamiltonian eigenstates.

With this in mind, the probability density can be expressed as

where we choose that in the initial time, the probability of finding both enantiomers is the same, so

, and we define

. This result suggests that the system is located in the states

or

with a probability of

therefore, the

and

states will oscillate with a period given by

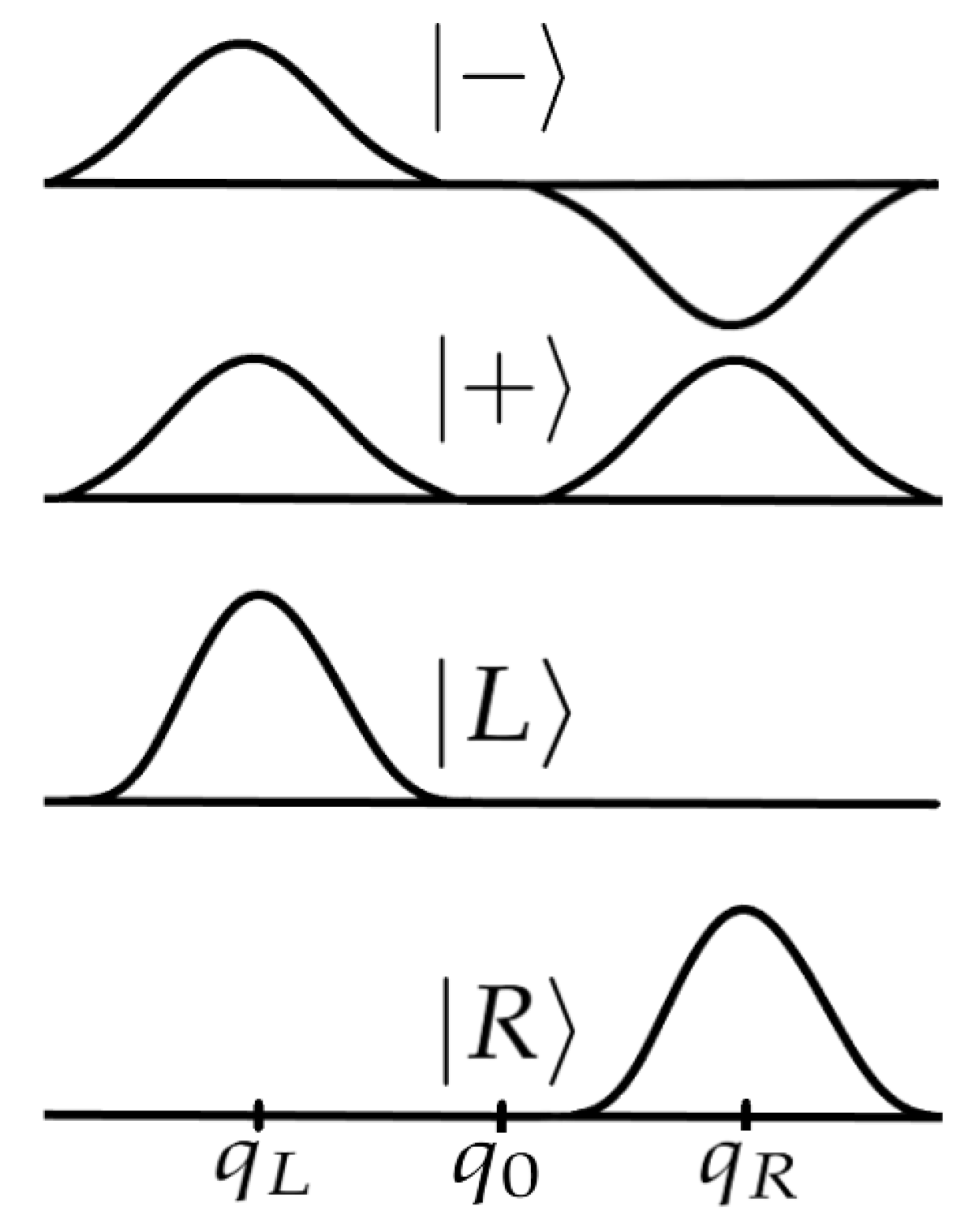

At this point, some comments are in order. It is well-known that chiral states are interconverted by the parity operator. The time-independent Hamiltonian eigenfunction and are also eigenfunctions of the parity operator (), but they have definite parity and, therefore, they can not represent chiral molecules. As a consequence, we have to define a different algebraic base which can be used to represent chiral molecules.

The condition which has to be fullfilled is

where we call

and

the states representing the

L and

R enantiomers. These states can be represented as

which are called chiral states or chiral base (see

Figure 2)). These states are no eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, being delocalized and having no defined energy (so it is necessary to work using the average of the energy). With this in mind, it is easy to reach an expression similar to Eq. (

10), and conclude that chiral molecules undergo an oscillating motion between

L and

R enantiomers, with a period of

With this in mind, we would like to remark that Hund performed two important considerations. First, he realized that although the energies

and

were not enough to exceed the potential barrier

, the transition between enantiomers could be observed, which is impossible in classical mechanics. This fact was the origin of the recognized tunneling effect in molecular physics, as we mentioned in the introduction. The second consideration is related to what is known as “Hund’s paradox" [

6], as pointed out by Harris and Stodolsky in [

15]. This paradox refers to the stability of some molecules in one specific enantiomeric state (e.g. CHFClBr, amino acids, and sugars), which is in principle impossible because there must be a periodic transition between enantiomers, in agreement with Eq. (

14). This paradox can be solved by the introduction of a new concept into our model: parity violation.

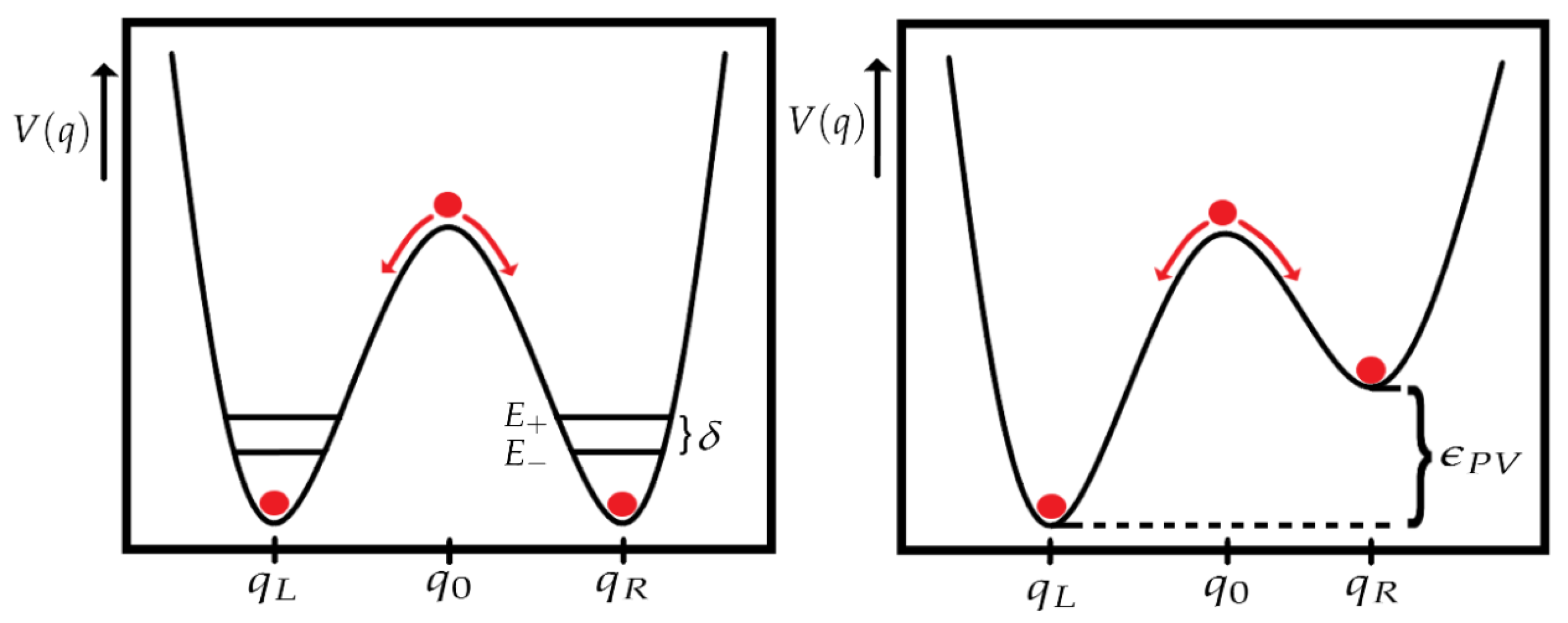

3. Parity violation

We have described chiral molecules in a two-state system without parity violation, described as a symmetric double well. We can now add parity violation to our model, which can be represented by a asymmetric double well, modifying the Hamiltonian [

15], which is expressed as

where

is the parity-violating term of the Hamiltonian (

), allowing the breakdown of the enantiomer degeneration. Besides,

,

and

are defined as

where we used the notation

. The

parameter is defined in the previous section, and it is related to the height of the potential well and the tunneling time (

), and

is related to the energy difference between the two potential wells. The

parameter is also known as PVED (Parity Violation Energy Difference) and represents the energy difference between the

L and the

R enantiomers (see

Figure 3)).

We will define

as the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (

15). It is remarkable that

are different from the definite parity states

and

, and they can be expressed in function of the chiral states as [

16,

17]

where

is the mixing angle and can be obtained as

The energies of the system are now given by the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (

17) and they are

with

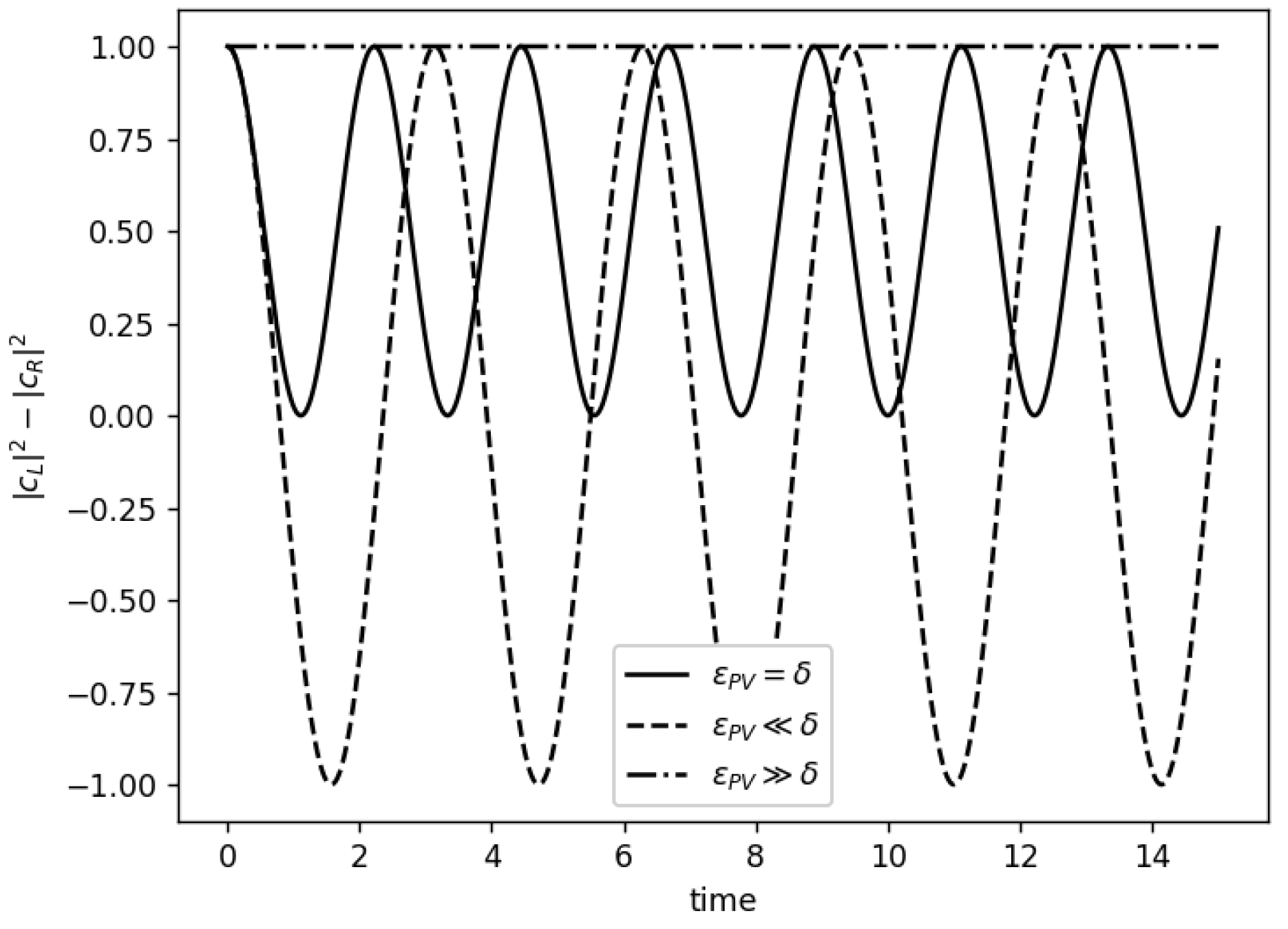

It is interesting to calculate the probability of a chiral molecule being located in its left or right state. For that, we have to express the wave function in the chiral base, obtaining

The evolution of

and

will be determined by the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (

1):

If we suppose that

,

and

, we obtain

being

and

the probability of the wave function to be in the

or

states, respectively. At this point, it is necessary to remark two specific cases [

16,

17]:

Case 1, :

This case implies that

(

) tending the energy eigenstates to be the chiral states

As we know, the states

and

are eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (

17), therefore they are localized states. In this particular case, the

and

states are also localized, being the chiral molecule stable in one of the two possible enantiomers. According to (

23),

, being the chiral molecule stable in the

L state, solving the aforementioned Hund’s paradox, as pointed out by Harris and Stodolsky [

15].

Case 2, :

This case implies that

(

), making sense to recover the non-parity violating case. If we use the Eq. (

17), and we impose

, we obtain the equations (

12) and (13), resulting in

As the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian

(

15) are equal to the eigenstates of

, we can conclude that there is no parity violation in this case. Both cases can be better understood with the help of

Figure 4.

At this point, some comments are in order. As we have seen, if parity violation affects our system, there could be an energy difference between enantiomers . In the other case, enantiomers are degenerate (). This behavior can be seen algebraically as follows:

Without parity violation

We already know the expressions for

and

without parity violation:

With this in mind, we can perform the next development

where we defined

. Therefore we have shown that

(

), confirming the enantiomer degeneration in the absence of parity violation.

With parity violation

In a parity-violating context, the chiral states can be represented in function of the Hamiltonian eigenstates as:

A process similar to the previous one can be performed:

If we use Eq. (

19) and taking

, we obtain

Therefore, the energy of the enantiomers is not the same () unless for ∀n∈ where .

In this section we have shown how parity violation can affect the Hamiltonian, changing its eigenstates and eigenvalues (energies) resulting sometimes in the apparent stability of chiral molecules. Therefore, an evident relationship between chiral molecules and PVED emerges, as well as with tunneling, being two principal concepts of study in the context of chiral molecules. Although tunneling is well-known theoretically and experimentally, there is still interest in applying novel theories in this framework, like instanton calculations [

18]. On the contrary, the PVED has not yet been detected, its relationship with molecular chirality constituting one of the most intriguing problems of [

19]. Before going into a brief review on theory and experiments designed to study parity violation in chiral molecules, we will give a bird’s eye view of the type of interactions which can show a parity-violating behavior.

4. Parity-violating interactions

As it was said before, the weak interaction is the unique fundamental force capable of producing parity violation in the SMPP. Despite that, there are other relevant theories beyond the SMPP that can violate parity, like axion interactions or modified gravity theories, which we would like to mention briefly.

The Axion is a particle not include in the SMPP, being a dark matter candidate (see [

20] for a recent review). A parity-violating electron-nucleon interaction mediated by an axion was proposed by Moody and Wilczek [

21] and is given by

where

,

is the scalar coupling constant of the axion to a nucleon,

is the pseudoscalar coupling constant to the electron,

represents the separation vector between the electron and the nucleon, and

is the mass of the axion. We would like to remark that the parity-violating behavior of some axion interactions makes them an interesting way to study PVED in chiral molecules [

22].

Other different parity violating mechanisms can be included in gravity. As commented in [

23], Leitner and Okubo were the first who pioneered this idea[

24]. After their proposal, Hari Dass wrote a parity-violating gravitational potential of the form (c = 1) [

25]

where

M represents the mass of the gravitating object,

is the separation vector from that mass to the test particle, whose spin and velocity are given by

and

, respectively.

Another relevant proposal is the Chern-Simons (CS) theory for gravity [

26], extending general relativity by considering not only the Einstein tensor but also the C-tensor [

27] and an extra pseudoscalar field (a field which violates parity).

Although there are other relevant theories, in thefollowing lines we will only consider electroweak interactions, which are routinely included in quantum chemistry calculations to study the PVED in chiral molecules.

4.1. Electroweak interaction

At the beginning of the discovery of the weak force, it was believed that it dependeded on charge transference (charged currents). Subsequently, in some attempts to unify weak and electromagnetic forces [

28,

29,

30], a new type of interaction emerged, based on weak neutral currents, which were capable of producing observable effects of parity violation in atoms [

11,

31]. With this in mind and knowing that molecules are essentially made by nucleons and electrons, we can use Quantum Field Theory and Feynman’s rules propose a Hamiltonian that could produce PVED in chiral molecules. This Hamiltonian represents the interaction between electrons and nucleons of the chiral molecule, mediated by a

boson (the propagator of the weak neutral current), and can be expressed as

where the notation

refers to the normal ordering of the

X operators,

is the Fermi constant,

are the Dirac matrices which satisfy

(

is the Minkowskian metric with signature

),

is Dirac adjoint,

,

,

, and

are coupling constants,

and

are the electron and nucleon fields respectively.

For simplicity, the study of PVED is usually done in a non-relativistic regime, leading to the non-relativistic electron-nucleon interaction Hamiltonian [

11,

32,

33]:

where

and

are the momentum and spin of the electrons,

is the nucleon density and the index

i and

j refers to a summation over electrons and nucleons respectively. Additionally, the weak charge,

, is given by

where

is the Weinberg angle and

N and

Z are the number of neutrons and protons respectively.

In order to understand why the Hamiltonian (

34) is used in the context of chiral molecules, we need to make some clarifications. On one hand, polar vectors violate parity as well as rotations do, while axial vectors get a minus sign under rotations. On the other hand, pseudoscalars violate parity and respect rotations, and scalars respect both of these symmetries. Concerning time inversion, time-odd and time-even refer to the violation or not of this symmetry.

Now, let us note that there are only two non-scalar terms in the Hamiltonian (

34). The first one is the momentum of the electrons

, which is a time-odd polar vector, and the second one is the spin of the electron

, which is a time-odd axial vector. This results in a time-even pseudoscalar behavior of the Hamiltonian (

34), violating parity while respecting time inversion. Importantly, these time-even pseudoscalars are used to define

true chirality, which leads to the possibility of producing PVED in chiral molecules (if the Hamiltonian also violates time inversion, it is defined as false chirality, and can not produce PVED in chiral molecules) [

34,

35,

36,

37].

5. Calculations of PVED

Although the Hamiltonian (

34) violates parity, there is still a problem in calculating the PVED. In the non-relativistic approximation, the molecular wave function is always real, while the parity-violating part of the Hamiltonian (

34) is purely imaginary. This led to a zero expectation value for

over the molecular wave function. There are two possible solutions to this problem. The first one is to implement a parity-odd perturbation operator into a fully relativistic four-component Dirac-Hartree-Fock framework treatment of the parity-violating energy differences in chiral molecules [

38]. The second one is to maintain a non-relativistic regime, adding a spin-orbit coupling to give a first-order correction to the wave function [

39]. That spin-orbit coupling can be written as

where

is the fine-structure constant and

is the electric field seen by an electron

i. Then, the ground state

is perturbed as

resulting in a term for the PVED different from 0, which is

At this point, an estimation of the PVED can be done. In one way, this estimation was performed in a work by Bouchiat and Bouchiat [

11]. In that work, they stated that, for dominant heavy atoms with atomic number

Z, the

part of the Eq. (

38) is of order

. By the other way, from atomic theory, we know that the

part of Eq. (

38) is of order

. With these considerations in mind, we can estimate that

which shows that the higher

Z, the higher the PVED. The Eq. (

39) is usually known as

scaling law, and it was used in numerical calculous in different works [

40,

41].

Although nowadays there are diffferent methodologies based on different levels for the theory employed, we would like to remarkable the CIS-RHF formalism [

42,

43], a formalism that emerged from critically analyzing calculations of electroweak quantum chemistry. This formalism is a perturbation-theory mixture of the ground RHF (restricted Hartree-Fock) with the CIS (configuration interaction singles) excited states. Using this approach, the authors found that the PVED in chiral molecules has essentially a tensor character

which transforms as a polar vector in its first index and as an axial vector in its second index, being this tensor a pseudoscalar. With this method in mind, they calculated

in typical chiral molecules, obtaining a PVED up to two orders of magnitude higher than reported using other methodologies. Please note that these enhancement has been confirmed by other groups in subsequent years [

44,

45,

46,

47].

Finally, we would like to remark that there are other interesting methods to mention. For example, if we want to study parity-violating potentials in chiral molecules with light nuclei, an interesting way is using the Breit-Pauli approximation [

48]. If molecules involving heavy atoms are considered, the Dirac-Fock theory does a nice job [

45,

47,

49].

6. Experiments searching the PVED

It is remarkable that, although the search for PVEDs has been an exhaustive work, it has not been detected yet, due to the high sensibility needed in the experiments. Up to this date, in our opinion, there are two promising experiments whose purpose is the detection of PVED in chiral molecules. One of them is located in Zürich, based on a proposal made by Quack in 1986 [

50] and the other one emerged in Paris in 1999 [

51] (see [

14] if more information is required). As an incomplete list, we would like to remark other experimental approaches working on parity-violating effects on chiral molecules [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63] (see [

64,

65] for more information about other experiments). Here we will briefly comment on the Zürich and Paris proposals.

Firstly we will expose the Zürich experiment, mainly developed before 1986 by Quack’s group [

50]. They use excited energy levels of achiral molecules with well-defined parity which connect both enantiomers by radiative electric dipole transition moments. They prepare coherent superpositions of parity-defined states in the fundamental state using those energy levels, following the temporal evolution of the molecular parity. From this,

can be obtained directly, which is the objective of the experiment (see section 4.2 of the review [

14] for more detailed information). Recently, they have achieved an experimental sensitivity (using

) of

[

66]. Such values have been found theoretically in chiral molecules with lighter nuclei than sulfur and chlorine [

67,

68,

69], so maybe such data can be of great interest to future experiments.

The other experiment was proposed by Letokhov in 1975 [

70,

71] in Paris. This experiment tries to measure the differences in the high-resolution spectrum in separate

L and

R enantiomers, which can have a transition frequency

,

for specific transitions. The energy difference between two molecular levels can be expressed in function of the transition frequency as

Recently, the group of the Laboratoire de Physique des Lasers in Paris achieved a sensitivity of

. Even more, it is expected that, for specific molecules composed of Ruthenium (Ru) and Osmium (Os) atoms, that measurement could be of the order of

[

72]. Therefore, we think we are close to observing the PVED in chiral molecules.

7. Discussion and conclusions

After concluding this brief review, we would like to mention possible extensions to study the interplay between tunneling and parity violation in chiral molecules. Once it is accepted that physical systems do no exist in isolation, and given that decoherence is an ubicuous feature of nature, it seems mandatory to include interactions between the chiral molecule under consideration and its surroundings. In this sense, some techniques of Caldeira-Leggett type were imported into the problem of stereomutation of chiral molecules, including parity violation effects [

73]. The main message one can get from these works is the following: in general, although the medium usually acts as some kind of dissipator [

74,

75], there are some cases where an enhancement of parity-violating effects due to the medium can occur [

73]. In this sense, we think that it would be interesting to treat chiral molecules as a open system by combining high-level theoretical descriptions of both the molecule, the surroundings and their interaction. Perhaps the medium can take a protagonic role in order to enhance or diminish the PVED.

Along this manuscript, we have briefly reviewed the interplay between parity violation and quantum tunneling in the context of chiral molecules. Firstly, we have given a more theoretical point of view to finally end with a brief experimental overview.

By using a simple quantum treatment to describe chiral molecules as a two-level system, and after defining a good algebraic base to describe chiral molecules, the necessity of introducing quantum tunneling between the L and R enantiomers emerged. Interestingly, the tunneling time is inversely proportional to the energy difference between the time-independent Hamiltonian eigenfunctions with definite parity, and , represented as in the manuscript. Subsequently, we have added parity violation as an essential ingrediant of our model, which gives place to an energy difference between the L and R enantiomers, the so-called parity-violating energy difference (PVED). The introduction of this new parameter changes the probability of the chiral molecule to be in the L or R states, resulting in the apparent stability of one of the possible enantiomers of a chiral molecule when the PVED is substantially higher than . That is, when parity violation overcomes the tunneling effects, a possible solution to the "Hund’s paradox" emerges.

Along the rest of the manuscript, we mentioned possible parity-violating interactions, like axion interactions or modified gravity theories, focusing on electroweak interactions. Specifically, we commented on the electron-nucleon interaction mediated by weak neutral currents as it is the most used way to study the PVED in chiral molecules. Although we have a well established parity-violating Hamiltonian, calculating the PVED is difficult task. Different methods and approximations have been proposed based on different levels of the theory employed. We have remarked some of them as the scaling law, the CIS-RHF formalism, the Breit-Pauli approximation, and the Dirac-Fock theory. Finally, we have commented on some experimental searches of the PVED, noticing that important progresses have been made along the last sixty years. Therefore, we think that we are finally close detect the PVED in chiral molecules.

Acknowledgments

D. M. -G. and S. M. -A. acknowledge Fundación Humanismo y Ciencia for financial support. P. B. acknowledges financial support from the Generalitat Valenciana through PROMETEO PROJECT CIPROM/2022/13.

References

- Newton, I. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica; Apud Guil. & Joh. Innys, 1687.

- Klein, M. Max Planck and the Beginnings of the Quantum Theory. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 1962, 1, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules. Physical Review 1926, 28, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavy, M. Quantum Theory of Tunneling; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2003.

- Hund, F. Zur Deutung der Molekelspektren II, Z. Phys. 1927, 42, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund, F. Zur Deutung der Molekelspektren III. Bemerkungen über das Schwingungs- und Rotationsspektrum bei Molekeln mit mehr als zwei Kernen. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 1927, 43, 805–826. [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin, L. Baltimore Lectures on Molecular Dynamics and the Wave Theory of Light; C.J Clay & Sons: London, UK, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, L.D. Parity and Optical Activity. Nature 1972, 238, 7–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.D.; Yang, C.N. Question of Parity Conservation in Weak Interactions.

- Wu, C.S.; Ambler, E.; Hayward, R.; Hoppes, D.; Hudson, R. An experimental test of parity conservation in beta decay. Phys. Rev 1957, 105, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchiat, M.A.; Bouchiat, C. Parity violation induced by weak neutral currents in atomic physics. J. Phys. France 1974, 35, 899–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkov, L.; Zolotorev, M. Parity violation in atomic bismuth. Physics Letters B 1979, 85, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.S.; Bennet, S.C.; Cho, D.; Masterson, B.P.; Roberts, J.L.; Tanner, C.E.; Wiemann, C.E. Measurement of Parity Nonconservation and an Anapole Moment in Cesium. Science 1997, 275, 1759–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, M.; Seyfang, G.; Wichmann, G. Perspectives on parity violation in chiral molecules: theory, spectroscopic experiment and biomolecular homochirality. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 10598–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Stodolsky, L. Quantum beats in optical activity and weak interactions. Physics Letters B 1978, 78, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargueño, P.; Gonzalo, I.; de Tudela, R.P. Detection of parity violation in chiral molecules by external tuning of electroweak optical activity. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 012110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargueño, P.; Gonzalo, I.; de Tudela, R.P.; Miret, S. Parity violation and critical temperature of non-interacting chiral molecules. Chemical Physics Letters 2009, 483, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, N.; Richardson, J.; Berger, R. Instanton calculations of tunneling splittings in chiral molecules. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2021, 42, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. Frontier experiments: Tough science. Nature 2012, 481, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzio, L.D.; Giannotti, M.; Nardi, E.; Visinelli, L. The landscape of QCD axion models. Physics Reports 2020, 870, 1–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J.E.; Wilczek, F. New macroscopic forces? Phys. Rev. D 1984, 30, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, K.; Kozlov, M.G.; Isaev, T.A.; Berger, R. Parity-nonconserving interactions of electrons in chiral molecules with cosmic fields. Physical Review A 2020, 102, 032816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortra-Urra, A.; Bargueño, P. Homochirality: A Perspective from Fundamental Physics. MDPI 2019, 11, 661. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, J.; Okubo, S. Parity, Charge Conjugation, and Time Reversal in the Gravitational Interaction. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B1542–B1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, N.D.H. Test for C, P, and T Nonconservation in Gravitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1976, 36, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Yunes, N. Chern–Simons modified general relativity. Physics Reports 2009, 480, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackiw, R.; Pi, S.Y. Chern-Simons modification of general relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 68, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glashow, S.L. Partial-symmetries of weak interactions. Nuclear Physics 1961, 22, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. A Model of Leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. Weak and electromagnetic interactions. Conf. Proc. C 1961, 22, 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Zel’dovich, Y.B. Parity Nonconservation in the First Order in the Weak-Interaction Constant in Electron Scattering and Other Effects. JETP 1959, 9, 682. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R. Chapter 4 - Parity-Violation Effects in Molecules. In Relativistic Electronic Structure Theory; Elsevier, 2004; Vol. 14, pp. 188–288.

- Ginges, J.; Flambaum, V. Violations of fundamental symmetries in atoms and tests of unification theories of elementary particles. Physics Reports 2004, 397, 63–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, L. Fundamental symmetry aspects of optical activity. Chemical Physics Letters 1981, 79, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, L. True and false chirality and parity violation. Chemical Physics Letters 1986, 123, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, L.D. False Chirality, Absolute Enantioselection and CP Violation: Pierre Curie’s Legacy. Magnetochemistry 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, D.; Bargueño, P.; Miret-Artés, S. On the role of true and false chirality in producing parity violating energy differences. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences (under review) 2023.

- Laerdahl, J.K.; Schwerdtfeger, P. Fully relativistic ab initio calculations of the energies of chiral molecules including parity-violating weak interactions. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 60, 4439–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegstrom, R.; Rein, D.W.; Sandars, P.G.H. Calculation of the parity nonconserving energy difference between mirror-image molecules. J. Chem. Phys 1980, 73, 2329–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zel’dovich, B.Y.; Saakyan, D.; Sobel’man, I. Energy difference between right-hand and left-hand molecules, due to parity nonconservation in weak interactions of electrons with nuclei. JETP Letters 1977, 25, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, D.; Hegstrom, R.; Sandars, P. Parity non-conserving energy difference between mirror image molecules. Physics Letters A 1979, 71, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Bakasov, T.K.H.; Quack, M., Ab Initio Calculation of Molecular Energies Including Parity Violating Interactions. In Chemical Evolution: Physics of the Origin and Evolution of Life: Proceedings of the Fourth Trieste Conference on Chemical Evolution, Trieste, Italy, 4–8 September 1995; Chela-Flores, J.; Raulin, F., Eds.; Springer Netherlands, 1996; pp. 287–296. 8 September.

- A. Bakasov, T.K.H.; Quack, M. Ab initio calculation of molecular energies including parity violating interactions. J. Chem. Phys 1998, 109, 7263–7285.

- Lazzeretti, P.; Zanasi, R. On the calculation of parity-violating energies in hydrogen peroxide and hydrogen disulphide molecules within the random-phase approximation. Chemical Physics Letters 1997, 279, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leardahl, J.K.; Schwerdtfeger, P. Fully relativistic ab initio calculations of the energies of chiral molecules including parity-violating weak interactions. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 60, 4439–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennum, A.C.; Helgaker, T.; Klopper, W. Parity-violating interaction in H2O2 calculated from density-functional theory. Chemical Physics Letters 2002, 354, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Schwerdtfeger, T.S.; van Stralen, J.; Visscher, L. Relativistic second-order many-body and density-functional theory for the parity-violation contribution to the C-F stretching mode in CHFClBr. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 012103.

- Berger, R. Breit interaction contribution to parity violating potentials in chiral molecules containing light nuclei. J Chem Phys 2008, 129, 154105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laerdahl, J.; Schwerdtfeger, P.; Quiney, H. Theoretical analysis of parity-violating energy differences between the enantiomers of chiral molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 3811–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, M. On the measurement of the parity violating energy difference between enantiomers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 132, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daussy, C.; Marrel, T.; Amy-Klein, A.; Nguyen, C.T.; Bordé, C.J.; Chardonnet, C. Limit on the Parity Nonconserving Energy Difference between the Enantiomers of a Chiral Molecule by Laser Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett 1999, 83, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, M. Experimental Tests of Parity Violation at Helical Polysilylene Level. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2001, 22, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, M. Mirror Symmetry Breaking in Helical Polysilanes: Preference between Left and Right of Chemical and Physical Origin. Symmetry 2010, 2, 1625–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, M.; Koe, J.; Mori, T.; Kimura, Y. Questions of Mirror Symmetry at the Photoexcited and Ground States of Non-Rigid Luminophores Raised by Circularly Polarized Luminescence and Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy: Part 1. Oligofluorenes, Oligophenylenes, Binaphthyls and Fused Aromatics. Molecules 2018, 23, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledbetter, M.; Crawford, C.; Pines, A.; Wemmer, D.; Knappe, S.; Kitching, J.; Budker, D. Optical detection of NMR J-spectra at zero magnetic field. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2009, 199, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darquié, B.; Stoeffler, C.; Shelovnikov, A.; Daussy, C.; Amy-Klein, A.; Chardonnet, C.; Zrig, S.; Guy, L.; Crassous, J.; Soulard, P.; Asselin, P.; Huet, T.; Achwerdtfeger, P.; Bast, R.; Saue, T. Progress toward the first observation of parity violation in chiral molecules by high-resolution laser spectroscopy 2010. 22, 870–884.

- DeMille, D.; Cahn, S.; Murphree, D.; Rahmlow, D.; Kozlov, M. Using Molecules to Measure Nuclear Spin-Dependent Parity Violation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, E.; Ammon, J.; Cahn, S.; DeMille, D. Demonstration of a Sensitive Method to Measure Nuclear-Spin-Dependent Parity Violation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 142501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Pérez, M.; Wall, T.; Hoekstra, S.; Bethlem, H. Preparation of an ultra-cold sample of ammonia molecules for precision measurements. Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy 2014, 300, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermott, A.; Hegstrom, R. Optical rotation of molecules in beams: the magic angle. Chemical Physics 2004, 305, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermott, A.; Hegstrom, R. A proposed experiment to measure the parity-violating energy difference between enantiomers from the optical rotation of chiral ammonia-like “cat” molecules. Chemical Physics 2004, 305, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, M.; Meijer, G. Cold Molecules: Preparation, Applications, and Challenges. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2009, 48, 6010–6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahamer, A.; Mahurin, S.; Compton, R.; House, D.; Laerdahl, J.; Lein, M.; Schwerdtfeger, P. Search for a Parity-Violating Energy Difference between Enantiomers of a Chiral Iron Complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 4470–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quack, M., Fundamental Symmetries and Symmetry Violations from High Resolution Spectroscopy. In Handbook of High-resolution Spectroscopy; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011; chapter 18, p. 659–722.

- Quack, M. How Important is Parity Violation for Molecular and Biomolecular Chirality? Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2002, 41, 4618–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietiker, P.; Miloglyadov, E.; Quack, M.; Schneider, A.; Seyfang, G. Infrared laser induced population transfer and parity selection in 14NH3: A proof of principle experiment towards detecting parity violation in chiral molecules. J. Chem. Phys 2015, 143, 244305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.; Gottselig, M.; Quack, M.; Willeke, M. Parity Violation Dominates the Dynamics of Chirality in Dichlorodisulfane. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2001, 10, 4195–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentner, R.; Quack, M.; Stohner, J.; Willeke, M. Wavepacket Dynamics of the Axially Chiral Molecule Cl-O-O-Cl under Coherent Radiative Excitation and Including Electroweak Parity Violation. . Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 12805–12822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, M.; Stohner, J.; Willeke, M. High-Resolution Spectroscopic Studies and Theory of Parity Violation in Chiral Molecules. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 2008, 59, 741–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letokhov, V. On difference of energy levels of left and right molecules due to weak interactions. Phys. Lett. A 1975, 53, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompanets, O.N.; Kukudzhanov, A.R.; Letokhov, V.S.; Gervits, L.L. Narrow resonances of saturated absorption of asymmetrical molecule CHFClBr and possibility of weak current detection in molecular physics. Opt. Commun. 1976, 19, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiechter, M.R.; Haase, P.A.B.; Saleh, N.; Soulard, P.; Tremblay, B.; Havenith, R.W.A.; Timmermans, R.G.E.; Schwerdtfeger, P.; Crassous, J.; Darquié, B.; Pasteka, L.F.; Borschwvsky, A. Toward Detection of the Molecular Parity Violation in Chiral Ru(acac)3 and Os(acac)3. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2022, 13, 10011–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargueño, P.; Peñate-Rodríguez, H.C.; Gonzalo, I.; Sols, F.; Miret-Artés, S. Friction-induced enhancement in the optical activity of interacting chiral molecules. Chemical Physics Letters 2011, 516, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñate-Rodríguez, H.C.; Dorta-Urra, A.; Bargueño, P.; Rojas-Lorenzo, G.; Miret-Artés, S. A Langevin Canonical Approach to the Dynamics of Chiral Systems: Populations and Coherences. Chirality, 25, 514–520.

- Peñate-Rodríguez, H.C.; Dorta-Urra, A.; Bargueño, P.; Rojas-Lorenzo, G.; Miret-Artés, S. A Langevin Canonical Approach to the Dynamics of Chiral Systems: Thermal Averages and Heat Capacity. Chirality, 26, 319–325.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).