Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. The current study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

2.2. Measures

3. Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and correlations

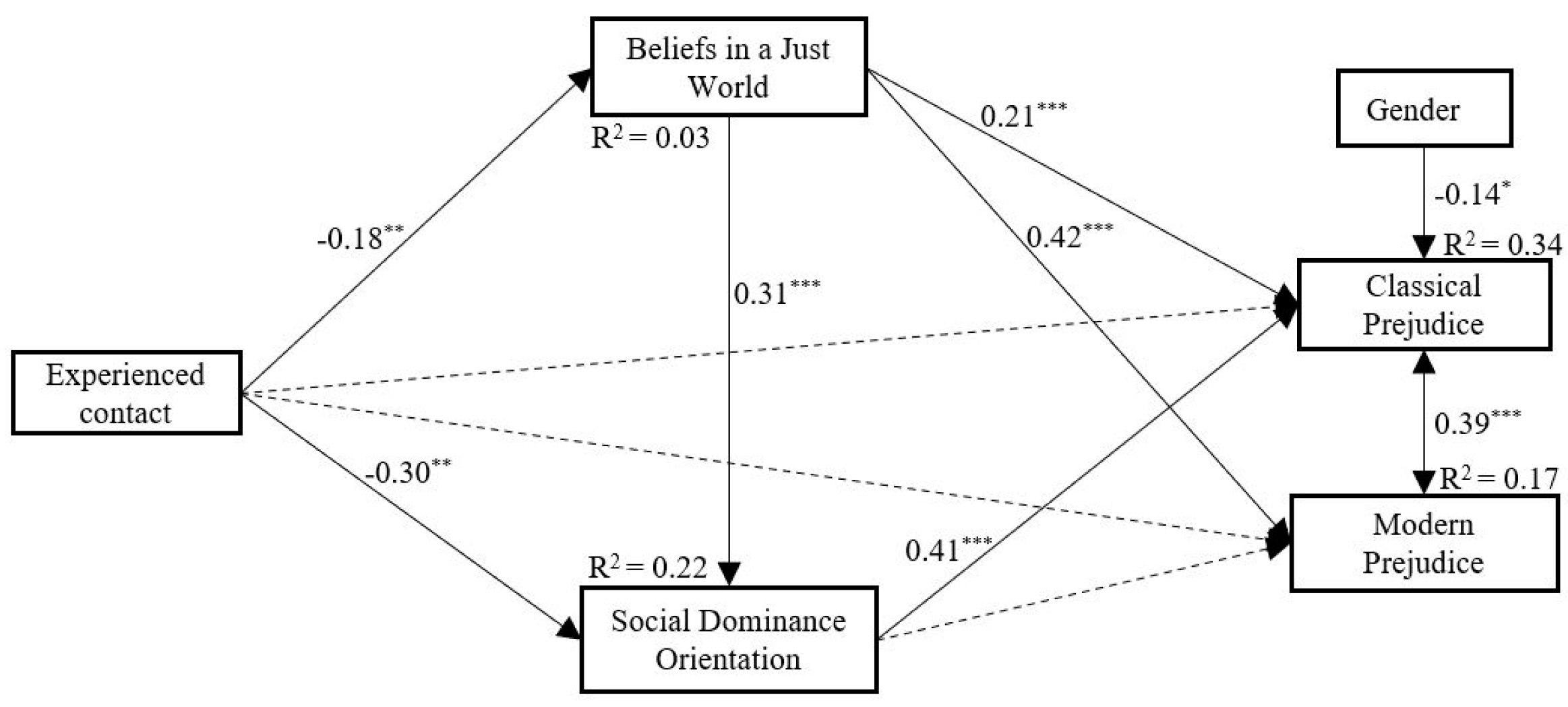

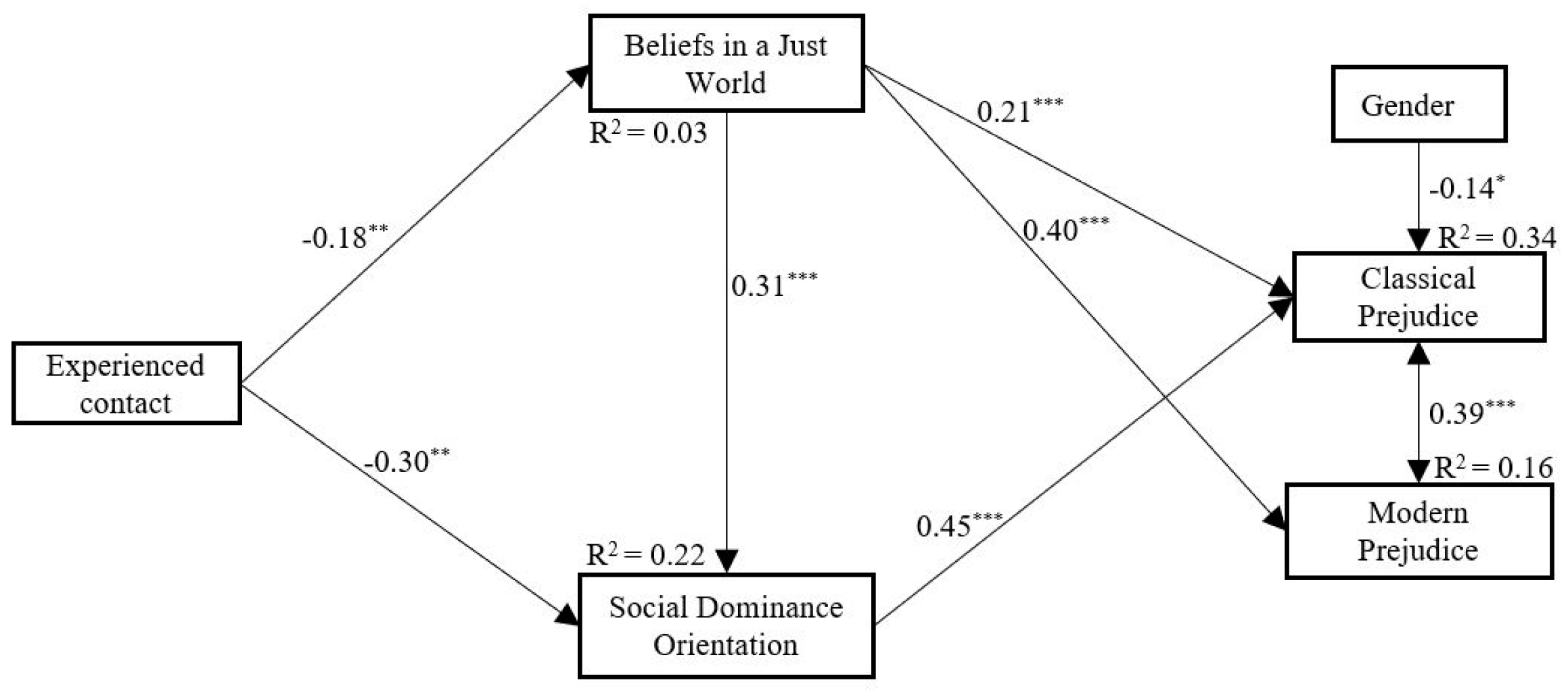

4.2. Mediation analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations and further studies

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R.; Tassé, M.J.; Verdugo, M.A. A Holistic Theoretical Approach to Intellectual Disability: Going Beyond the Four Current Perspectives. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2018, 56, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. , 5th ed.APA, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, D.C, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- Hamdani, Y.; Ary, A.; Lunsky, Y. Critical Analysis of a Population Mental Health Strategy: Effects on Stigma for People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2017, 10, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, N.; Ali, A.; Scior, K. Stigma Experienced by Family Members of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Multidimensional Construct. BJPsych open 2018, 4, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenorio, M.; Donoso, J.; Ali, A.; Hassiotis, A. Stigma Toward Persons with Intellectual Disability in South America: A Narrative Review. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2020, 17, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trani, J.-F.; Moodley, J.; Anand, P.; Graham, L.; Thu Maw, M.T. Stigma of Persons with Disabilities in South Africa: Uncovering Pathways from Discrimination to Depression and Low Self-Esteem. Social Science & Medicine 2020, 265, 113449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.; Scior, K. Tackling Stigma Associated with Intellectual Disability among the General Public: A Study of Two Indirect Contact Interventions. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2013, 34, 2200–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO World Mental Health Report. Transforming Mental Health for All 2022.

- Brandes, J.A.; Crowson, H.M. Predicting Dispositions toward Inclusion of Students with Disabilities: The Role of Conservative Ideology and Discomfort with Disability. Soc Psychol Educ 2009, 12, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowson, H.M.; Brandes, J.A. Predicting Pre-Service Teachers’ Opposition to Inclusion of Students with Disabilities: A Path Analytic Study. Soc Psychol Educ 2014, 17, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.R.; Wilson, M.S. Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation Predict Rejection of Science and Scientists. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2021, 24, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowson, H.M.; Brandes, J.A.; Hurst, R.J. Who Opposes Rights for Persons with Physical and Intellectual Disabilities? J Applied Social Pyschol 2013, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Chani, M.M.; Moreno, C.P.; Reeder, J.A.; Zuckerman, K.E.; Lindly, O.J. Perceived Community Disability Stigma in Multicultural, Low-Income Populations: Measure Development and Validation. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2021, 115, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Unabridged, 25th anniversary ed.; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co: Reading, Mass, 1954; ISBN 978-0-201-00178-5. [Google Scholar]

- Akrami, N.; Ekehammar, B.; Claesson, M.; Sonnander, K. Classical and Modern Prejudice: Attitudes toward People with Intellectual Disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2006, 27, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConahay, J.B.; Hardee, B.B.; Batts, V. Has Racism Declined in America?: It Depends on Who Is Asking and What Is Asked. Journal of Conflict Resolution 1981, 25, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco Servidio; Stefano Boca Pregiudizio classico e moderno nei confronti dei richiedenti asilo: un contributo alla validazione italiana della Prejudice Against Asylum Seekers Scale (PAAS). Psicologia sociale 2021, 99–121. [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R.; Marcone, R. Classical and Modern Prejudice towards Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities: A Study on a Sample of Italian University Students. The Social Science Journal 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelmann, A.; Heinemann, K.S. Preventing Prejudice and Improving Intergroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analysis of Child and Adolescent Training Programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2014, 35, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcone, R.; Caputo, A.; Esposito, S.; Senese, V.P. Prejudices towards People with Intellectual Disabilities: Reliability and Validity of the Italian Modern and Classical Prejudices Scale: Prejudices towards People with Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2019, 63, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scior, K.; Hamid, A.; Hastings, R.; Werner, S.; Belton, C.; Laniyan, A.; Patel, M.; Kett, M. Intellectual Disability Stigma and Initiatives to Challenge It and Promote Inclusion around the Globe. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2020, 17, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Uyaroğlu, A.K. The Relationship between Beliefs toward Mental Illnesses, Empathic Tendency and Social Distancing in University Students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 2022, 41, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulya, N.; Fehérvári, A. The Impact of Literary Works Containing Characters with Disabilities on Students’ Perception and Attitudes towards People with Disabilities. International Journal of Educational Research 2023, 117, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Kostizak, K.; Stevens, S.; Cronin, C.; Ramaiya, A.; Paddidam, P. Measurement and Conceptualisation of Attitudes and Social Norms Related to Discrimination against Children with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 2022, 69, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahdi, G.H.; Elhadi, A.; Schwab, S. The Positive Impact of Knowledge and Quality of Contact on University Students’ Attitudes towards People with Intellectual Disability in the Arab World. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2020, 106, 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, J.E.; Cruz, R.A.; Knollman, G.A. Increasing Positive Attitudes toward Individuals with Disabilities through Community Service Learning. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2017, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskin, P.R.; Reiser-Robbins, C.; Kwon, S. Attitudes of Undergraduate Students Toward Persons With Disabilities: Exploring Effects of Contact Experience on Social Distance Across Ten Disability Types. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 2018, 62, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orm, S.; Blikstad-Blumenthal, C.; Fjermestad, K. Attitudes toward People with Intellectual Disabilities in Norway. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J. The Belief in a Just World; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1980; ISBN 978-1-4899-0450-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, B. The Metaphysical Model of Disability: Is This a Just World? Develop Med Child Neuro 2021, 63, 240–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, G.; Otto, K. Personal Belief in a Just World and Conscientiousness: A Meta-analysis, Facet-level Examination, and Mediation Model. Br. J. Psychol. 2021, 112, 92–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizer, G.Y.; Hart, J.; Jekogian, A.M. Belief in a Just World and Social Dominance Orientation: Evidence for a Mediational Pathway Predicting Negative Attitudes and Discrimination against Individuals with Mental Illness. Personality and Individual Differences 2012, 52, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, C.L.; Sutton, R. Belief in a Just World. In Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Sabbagh, C., Schmitt, M., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4939-3215-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrams, A. Less Illusion of a Just World in People with Formally Diagnosed Autism and Higher Autistic Traits. J Autism Dev Disord 2021, 51, 3733–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Lan, N.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. How Does Social Anxiety Affect Mobile Phone Dependence in Adolescents? The Mediating Role of Self-Concept Clarity and Self-Esteem. Curr Psychol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litam, S.D.A.; Balkin, R.; Hendricks, L. Assessing Worry, Racism, and Belief in a Just World. Jour of Counseling & Develop 2022, 100, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1999; ISBN 978-1-139-17504-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekehammar, B.; Akrami, N.; Gylje, M.; Zakrisson, I. What Matters Most to Prejudice: Big Five Personality, Social Dominance Orientation, or Right-Wing Authoritarianism? Eur J Pers 2004, 18, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.E.; Basow, S.A. College Students’ Attitudes Toward Mental Illness: An Examination of the Stigma Process. J Appl Social Pyschol 2007, 37, 2877–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C.G.; Duckitt, J. The Ideological Legitimation of the Status Quo: Longitudinal Tests of a Social Dominance Model. Political Psychology 2010, 31, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, M.; Björklund, F. Structural Modeling of Generalized Prejudice: The Role of Social Dominance, Authoritarianism, and Empathy. Journal of Individual Differences 2007, 28, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keersmaecker, J.; Roets, A. All Victims Are Equally Innocent, but Some Are More Innocent than Others: The Role of Group Membership on Victim Blaming. Curr Psychol 2020, 39, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldmeadow, J.; Fiske, S.T. System-Justifying Ideologies Moderate Status = Competence Stereotypes: Roles for Belief in a Just World and Social Dominance Orientation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, J. A Dual-Process Cognitive-Motivational Theory of Ideology and Prejudice. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier, 2001; Vol. 33, pp. 41–113 ISBN 978-0-12-015233-9.

- Duckitt, J. Differential Effects of Right Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation on Outgroup Attitudes and Their Mediation by Threat From and Competitiveness to Outgroups. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2006, 32, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Roccato, M. Una Banca Di Item per Misurare l’orientamento Alia Dominanza Sociale in Italia. [An Item Bank for Measuring Social Dominance Orientation in Italy.]. Testing Psicometria Metodologia 2005, 12, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lipkus, I. The Construction and Preliminary Validation of a Global Belief in a Just World Scale and the Exploratory Analysis of the Multidimensional Belief in a Just World Scale. Personality and Individual Differences 1991, 12, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, A.; Hewstone, M. Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Toward Immigrants in Italy: The Mediational Role of Anxiety and the Moderational Role of Group Salience. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2003, 6, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Maras, P.; Masser, B.; Vivian, J.; Hewstone, M. Life on the Ocean Wave: Testing Some Intergroup Hypotheses in a Naturalistic Setting. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2001, 4, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozich, B.C.; Kenworthy, J.B.; Voci, A.; Hewstone, M. What’s Past Is Prologue: Intergroup Emotions and Trust as Mediating the Links between Prior Intergroup Contact and Future Behavioral Tendencies. TPM - Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Jamovi The Jamovi Project 2022. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Methodology in the social sciences; Fourth edition.; The Guilford Press: New York, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-2335-1. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behavior Research Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. Right-Wing Authoritarianism; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, 1981; ISBN 978-0-88755-124-6. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, B.E.; Kite, M.E. Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination; Thrid Edition.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York ; London, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-94752-8.

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced contact | 2.40 | 2.57 | 0.12 | -1.19 |

| Social Dominance Orientation | 1.53 | 0.32 | 0.93 | 1.48 |

| Beliefs in a Just World | 2.64 | 0.87 | 0.20 | -0.34 |

| Classical prejudice | 1.58 | 0.43 | 0.95 | 0.72 |

| Modern prejudice | 2.10 | 0.43 | -0.34 | -0.48 |

| Age | 23.02 | 2.48 | 1.20 | 2.34 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experienced contact | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2. Social Dominance Orientation | -0.35*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 3. Beliefs in a Just World | -0.18** | 0.36*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 4. Classical prejudice | -0.28*** | 0.53*** | 0.37*** | 1.00 | |||

| 5. Modern prejudice | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.40*** | 0.42*** | 1.00 | ||

| 6. Age | -0.02 | 0.07 | -0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |

| 7. Gender | 0.05 | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.17* | -0.01 | -0.06 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).