Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

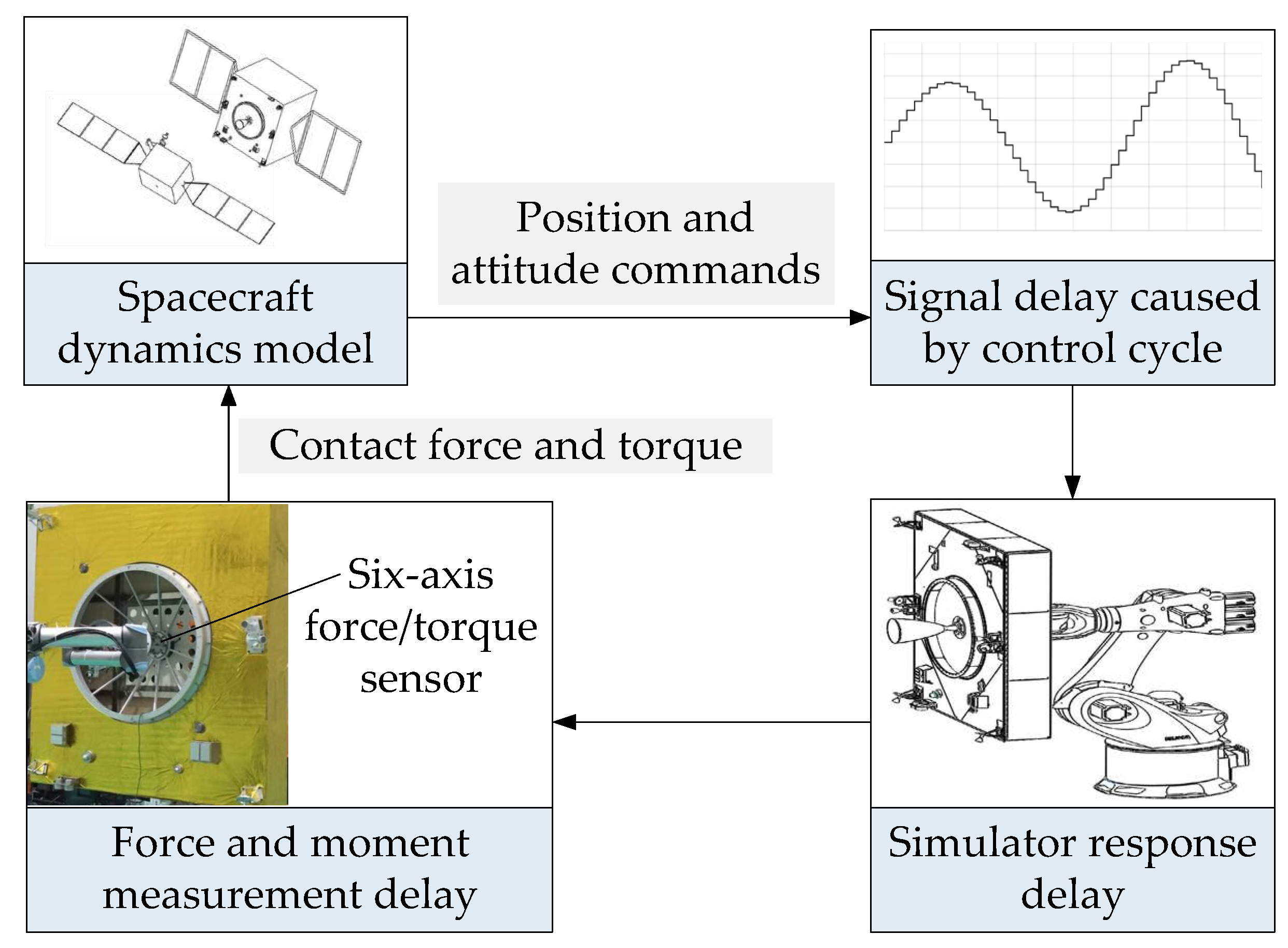

2. Effect of Different Delays on SITS Stability

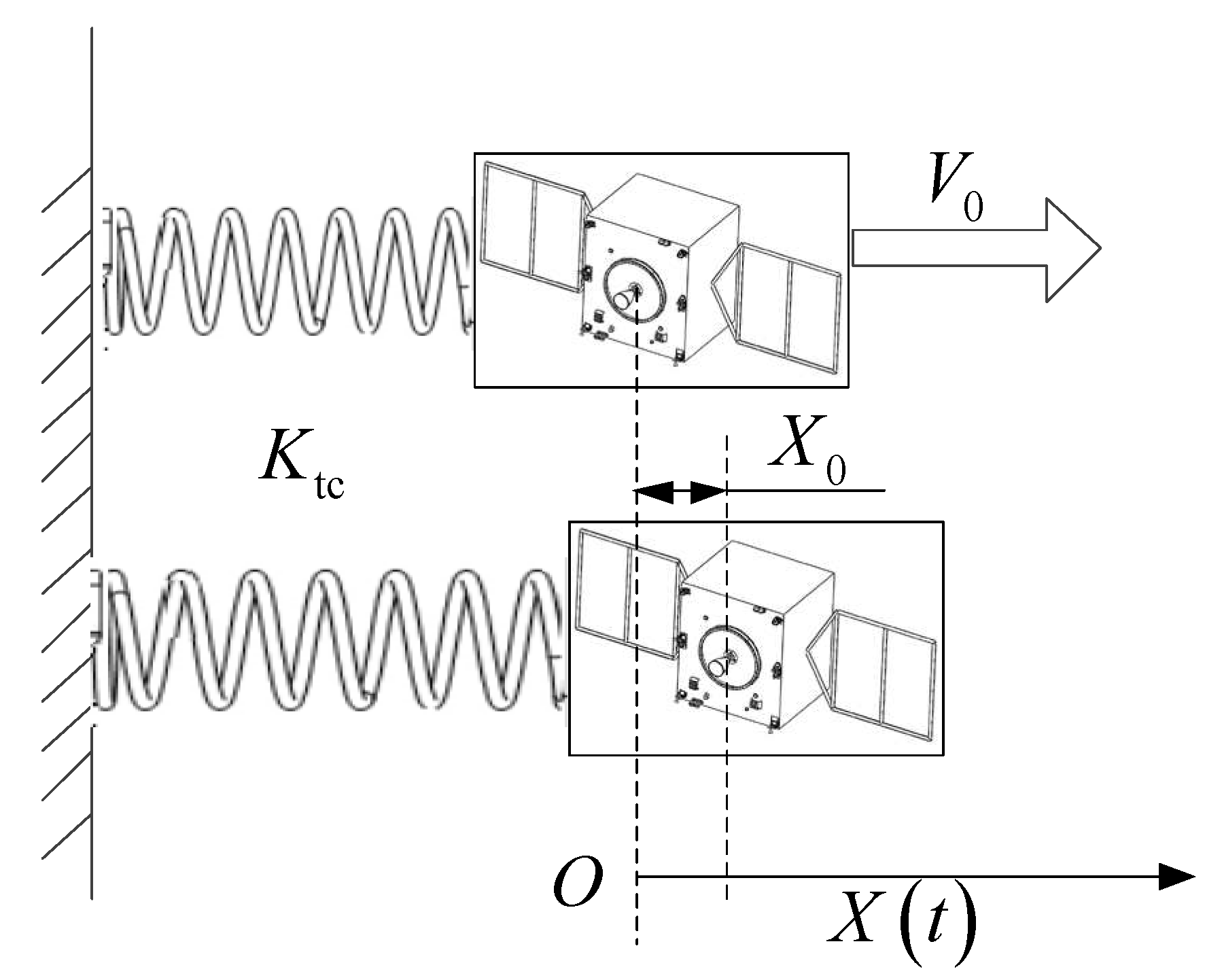

2.1. Effect of Force Measurement Delay on System Stability

2.2. Effect of Control Cycle on System Stability

2.3. Effect of Simulator Response Delay (SRD) on System Stability

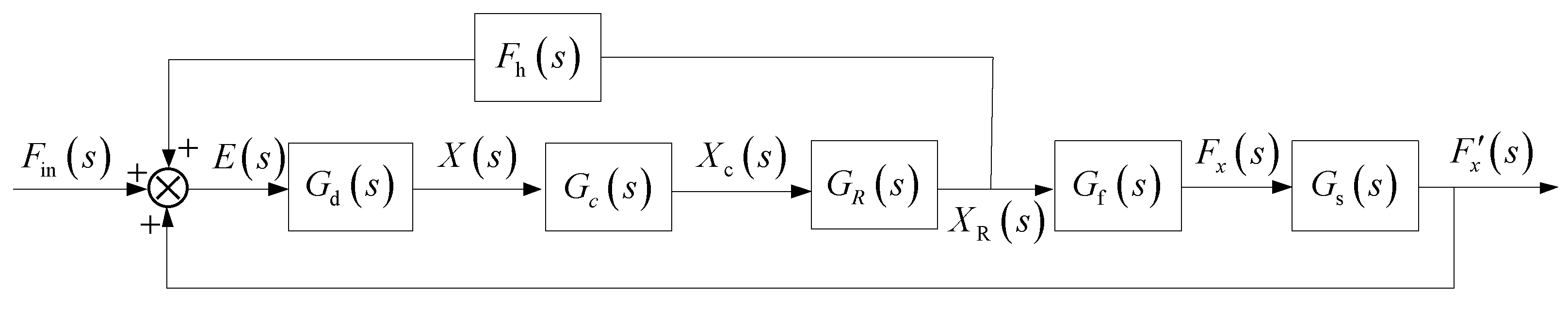

3. Mathematical Modeling and Stability Analysis of Hybrid Simulator

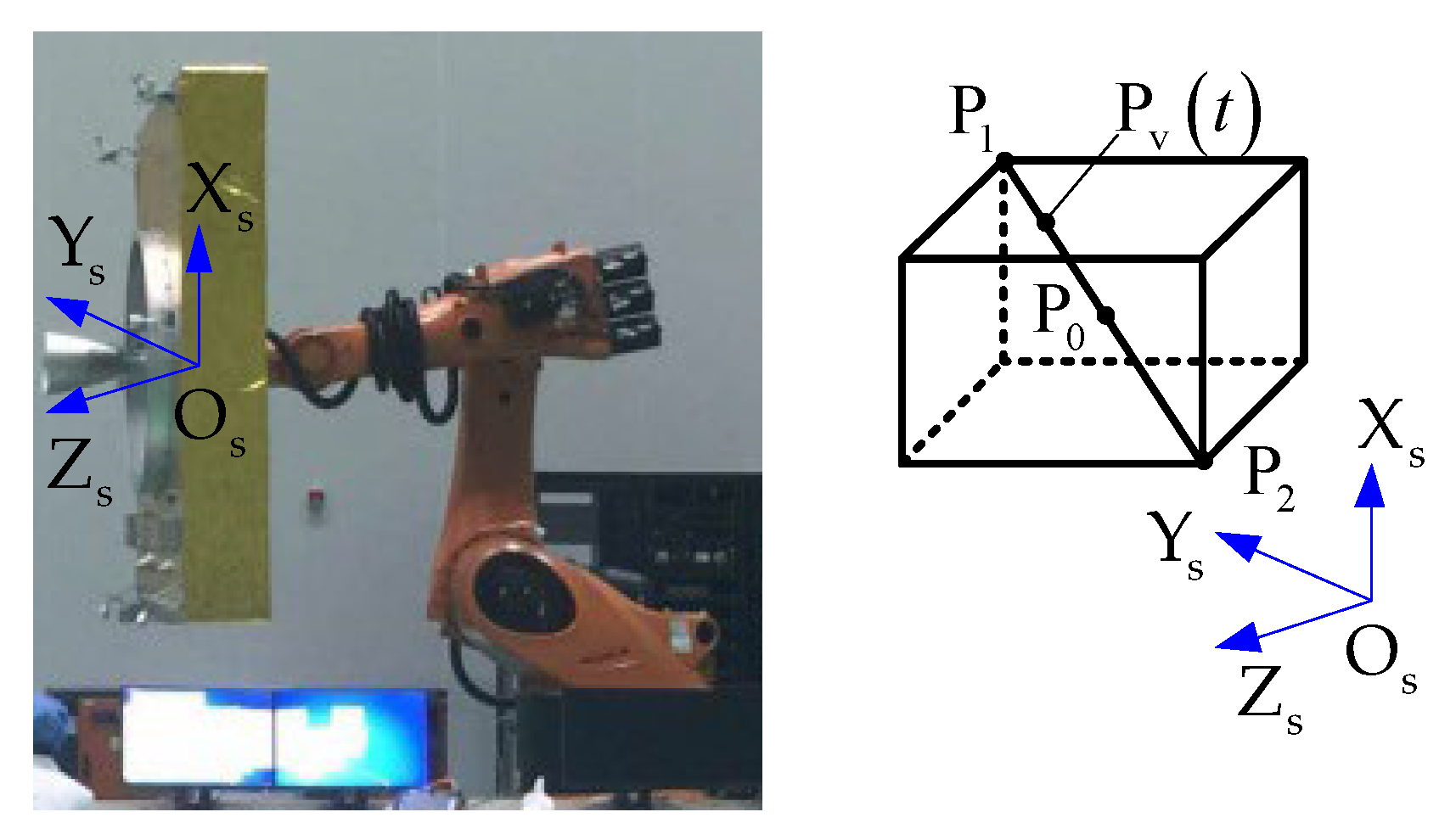

3.1. Mathematical Modeling of Hybrid Simulator

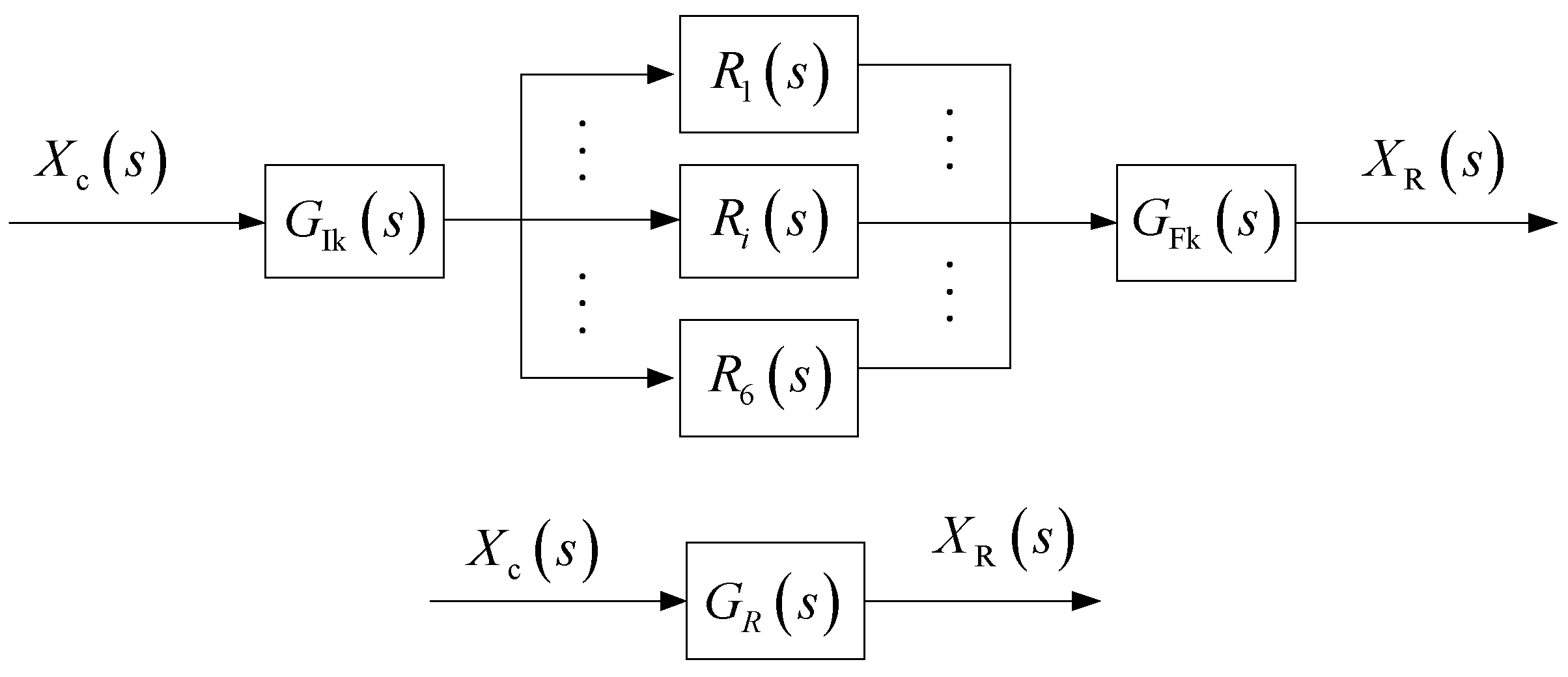

3.2. Model Identification of SITS

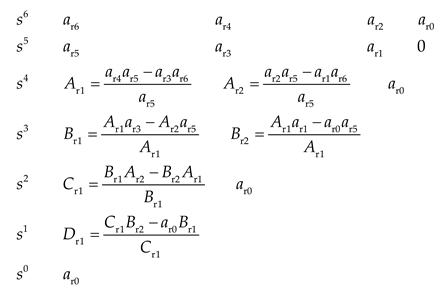

3.3. Stability and Steady-State Error Analysis

4. Delay Compensation Method of Hybrid Simulator

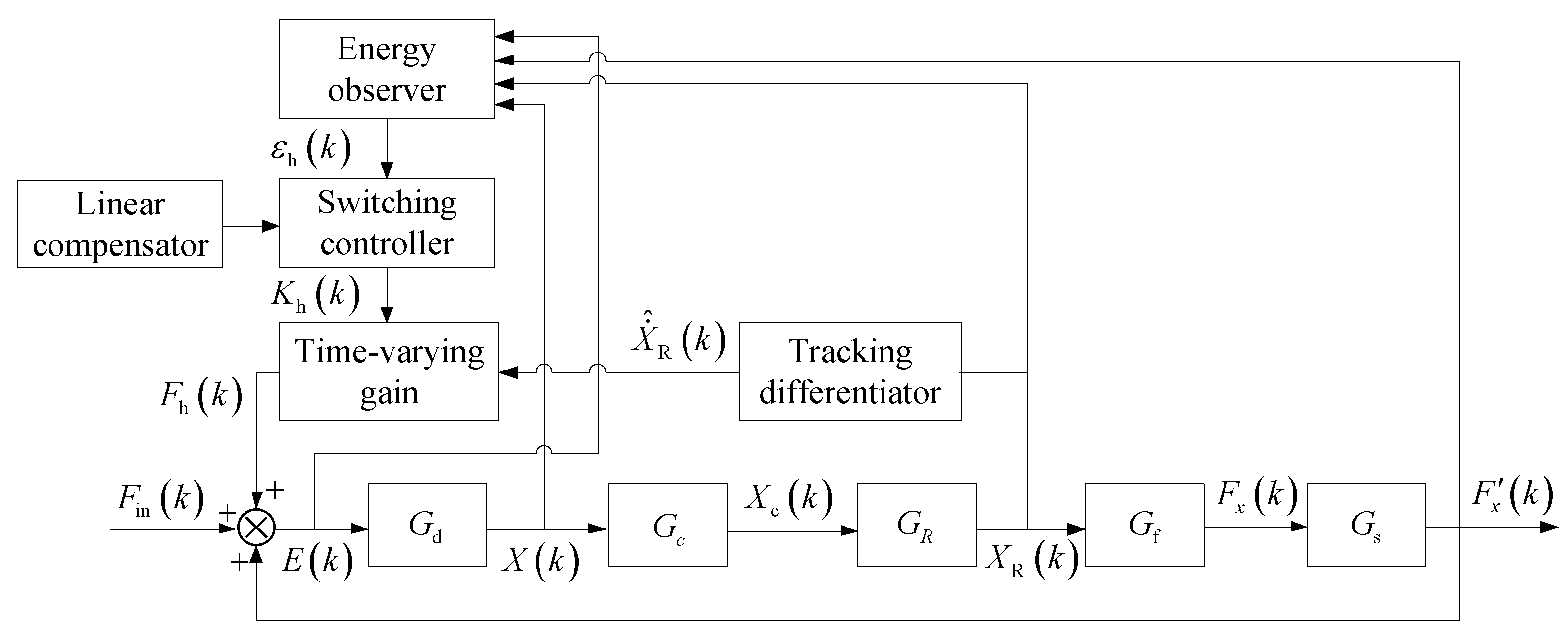

4.1. Modelling of Switching Compensator with Variable Gain

4.2. Velocity Estimation Based on Tracking Differentiator

5. Simulation Study

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | m/s | |

| 500 | Kg | |

| 20000 | N/m | |

| 0.002 | s | |

| 0.004 | s | |

| 50 | N·s/m | |

| 0.025 | m | |

| 6π | rad/s | |

| 0.002 | s | |

| 1501 |

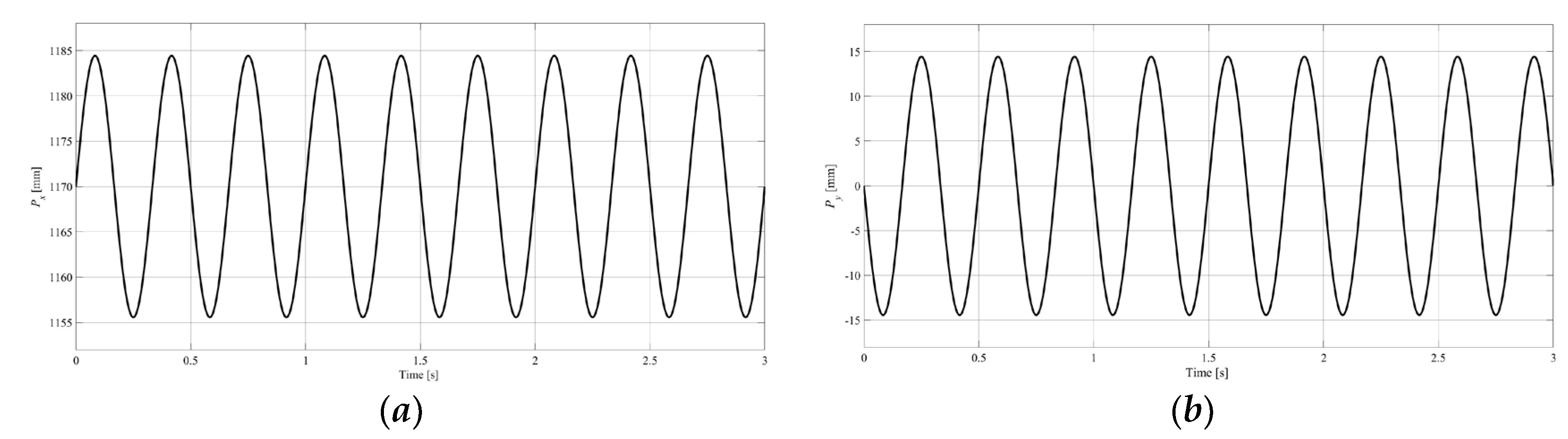

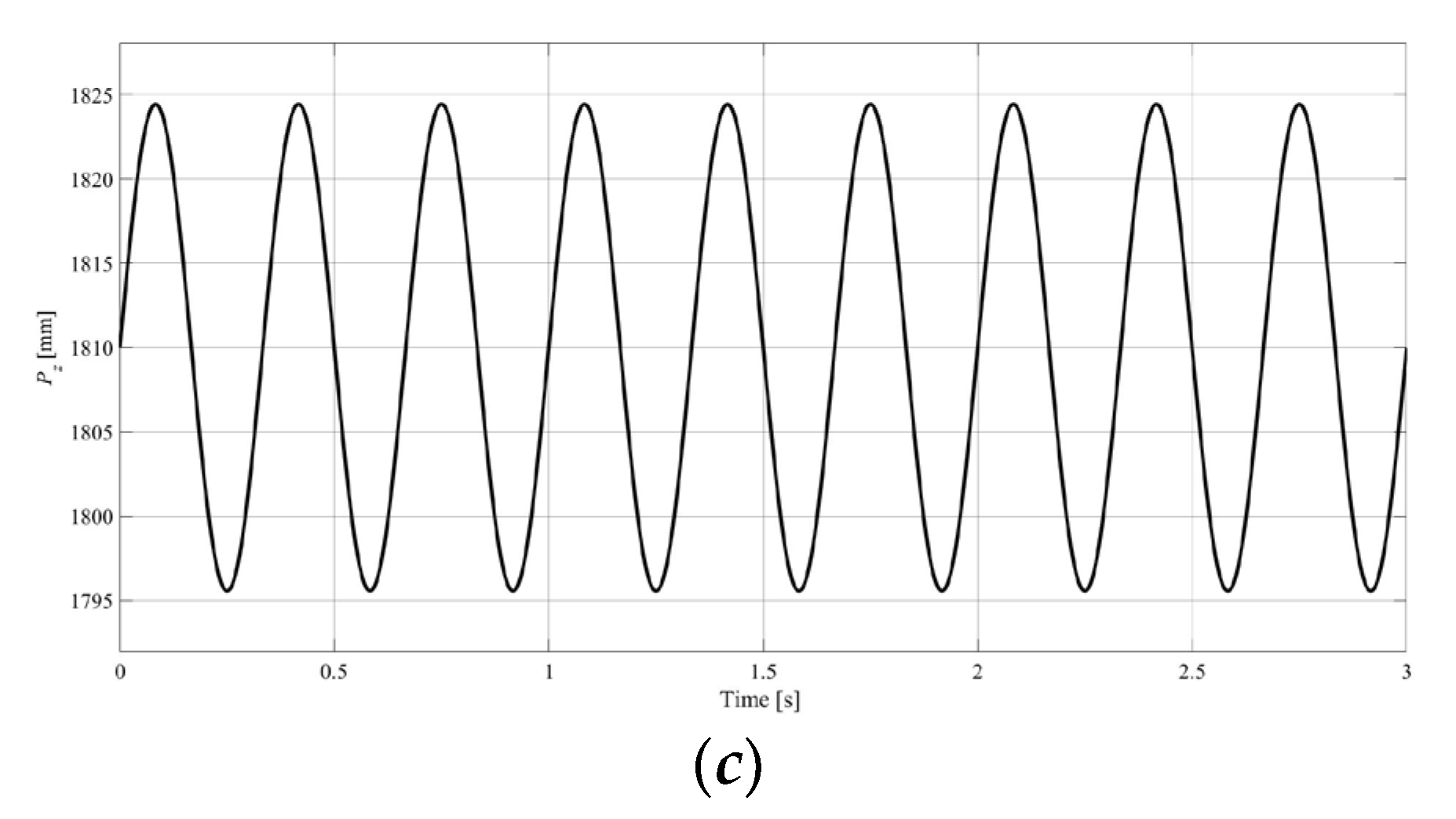

5.1. Simulation Verification of Delays Effect on the SITS Stability of 1D Undamped Vibration

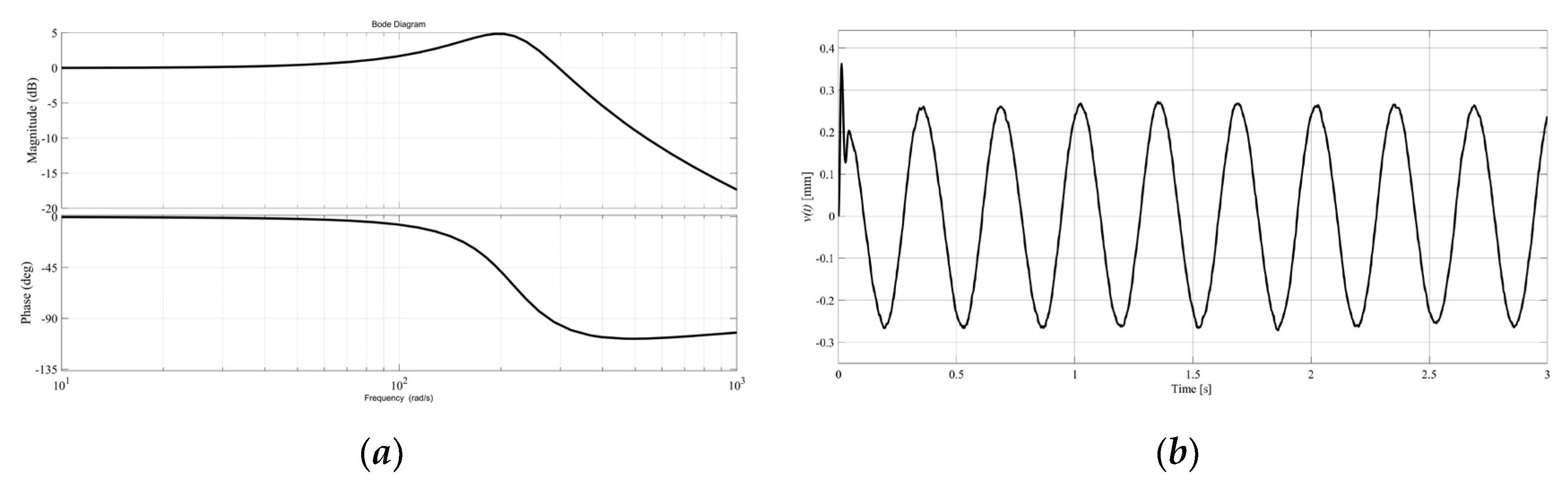

5.2. Identification Simulation of SITS

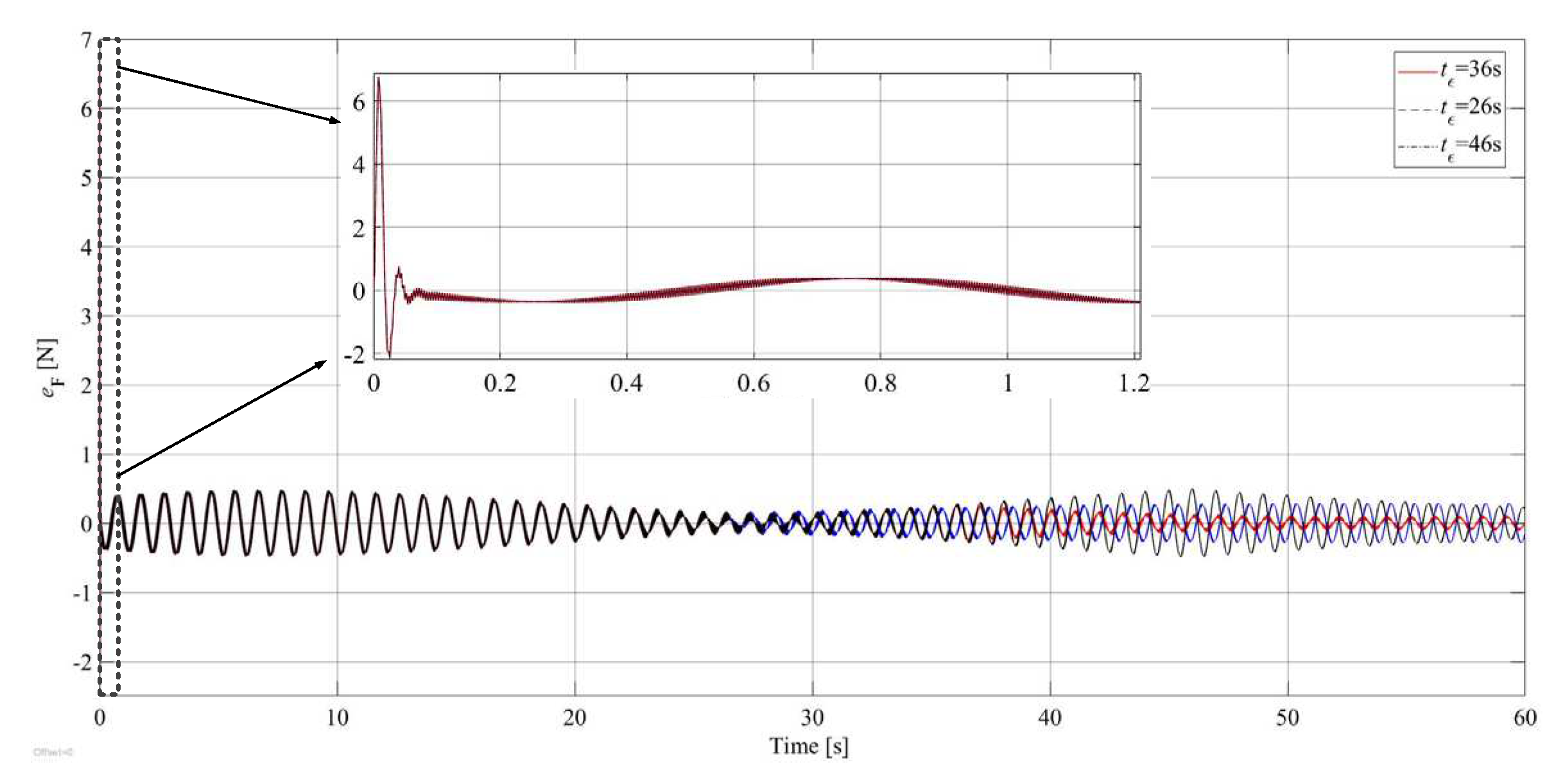

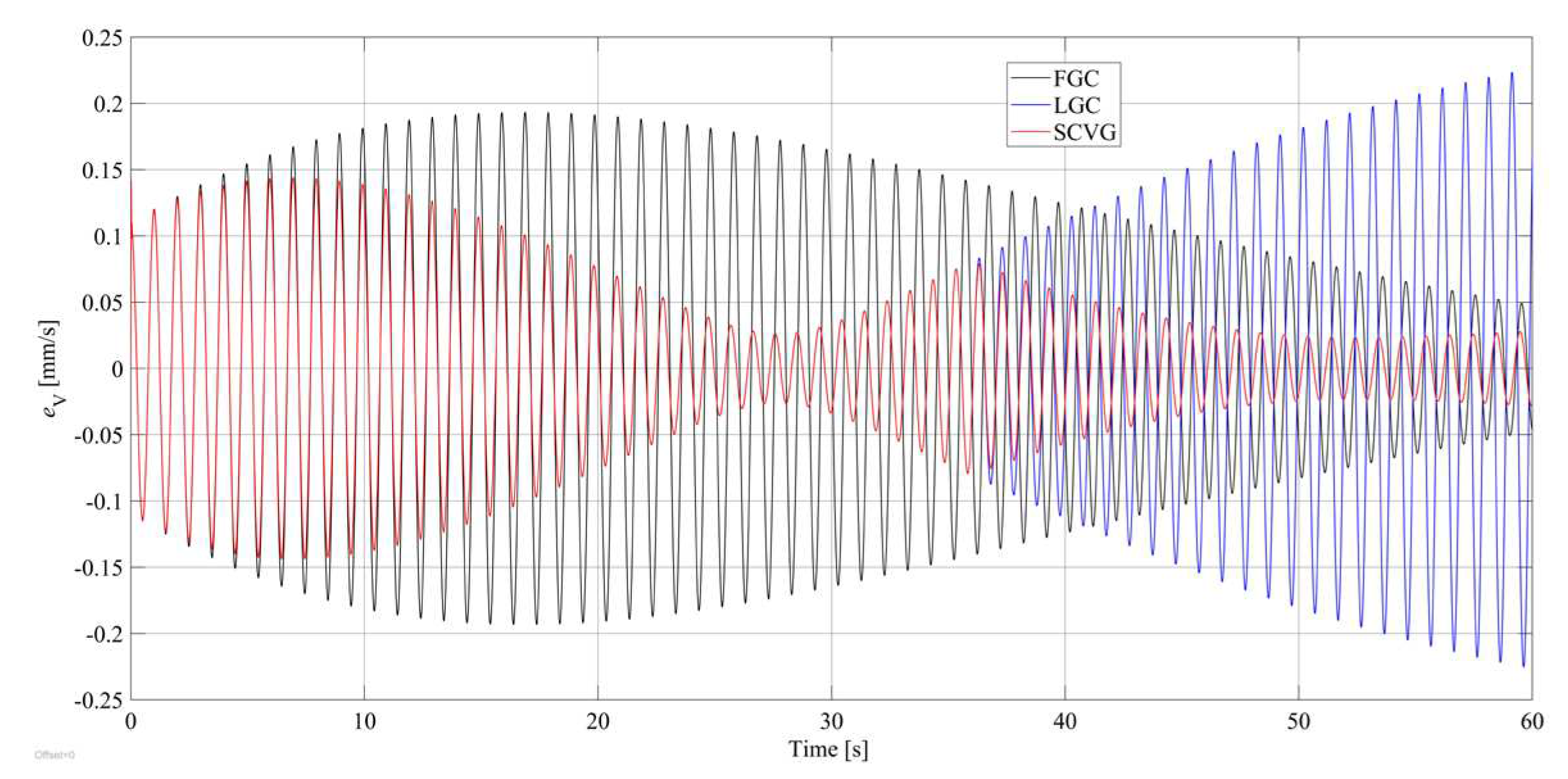

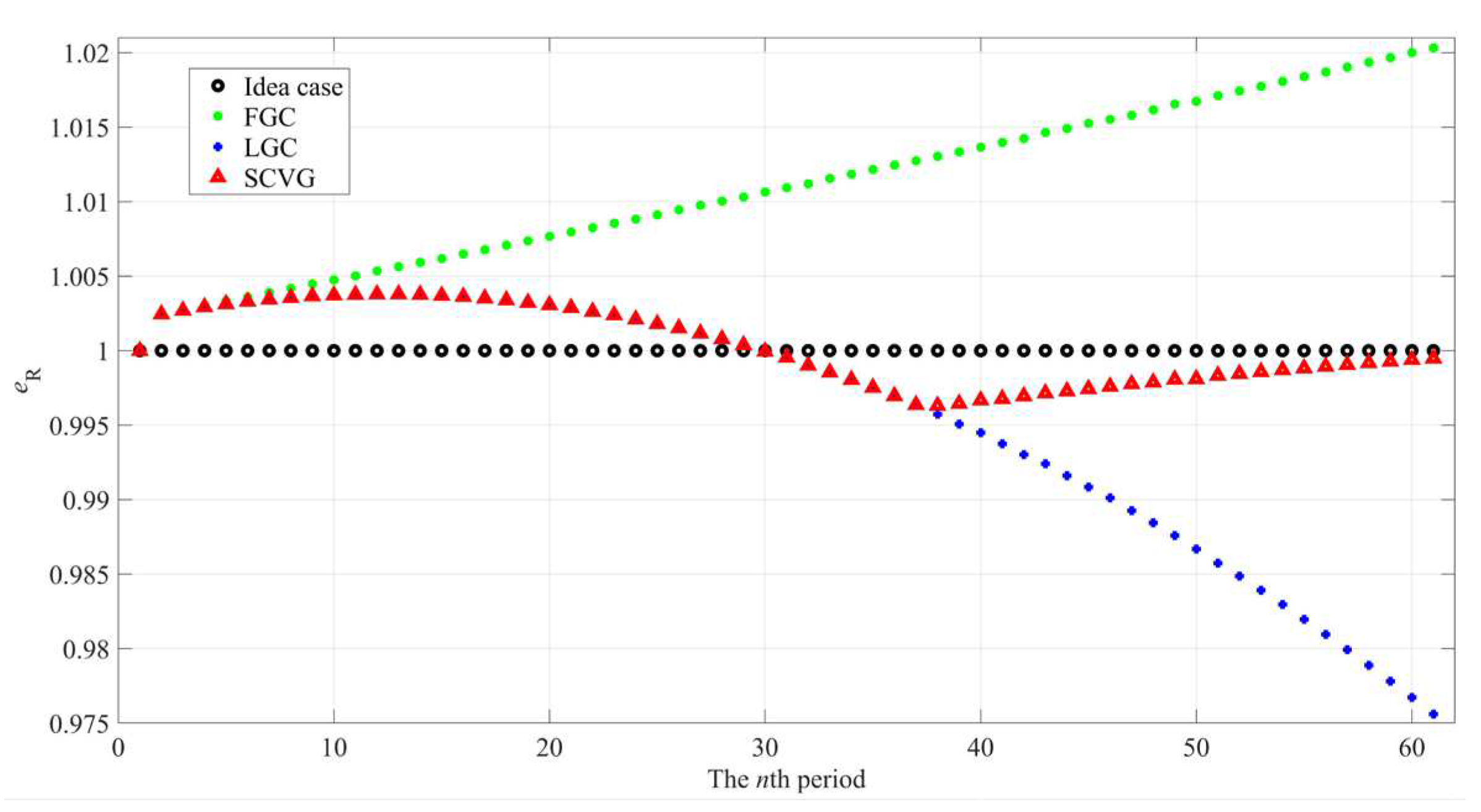

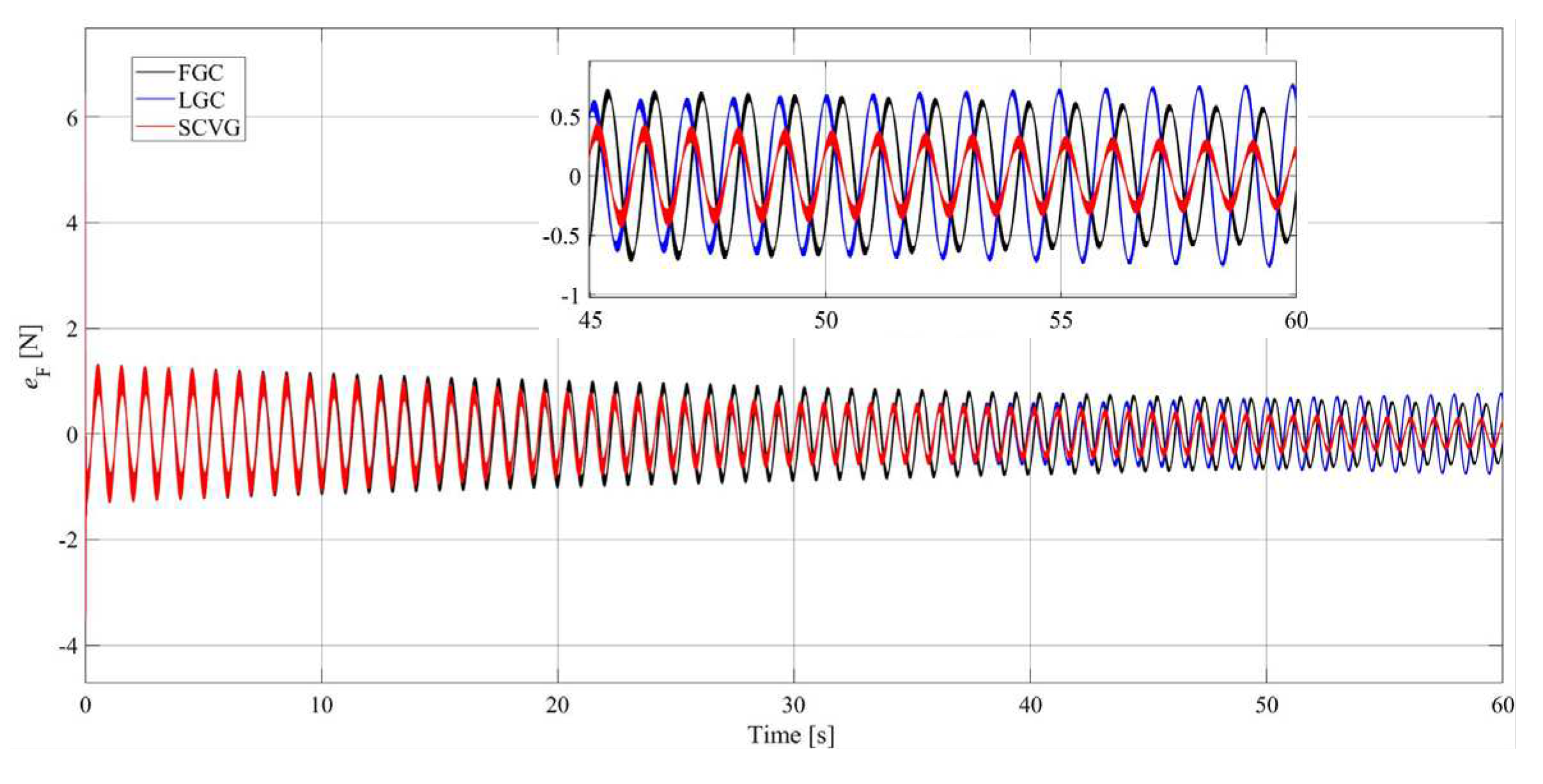

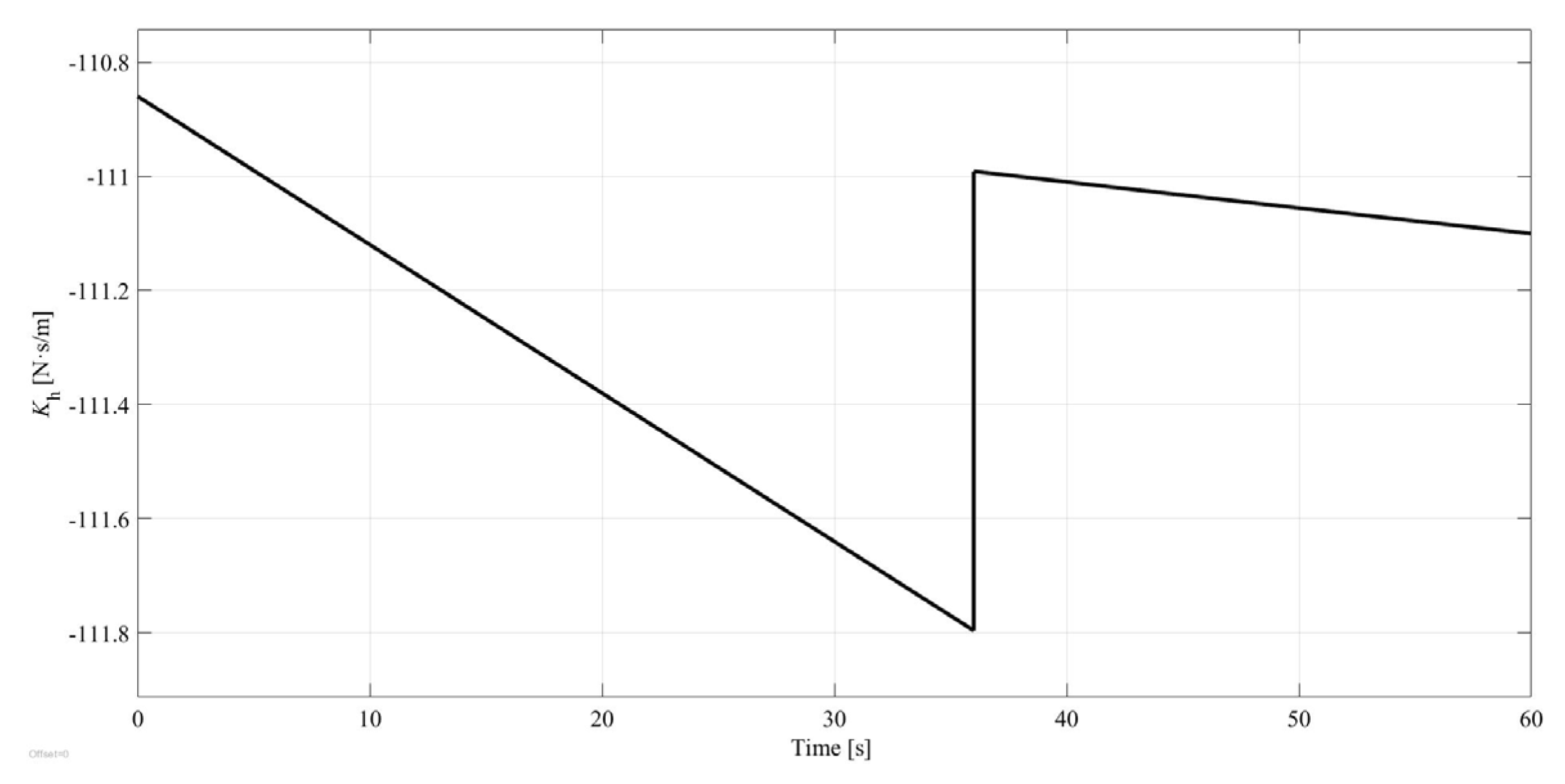

5.3. Simulation Verification of the Effect for SCVG

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keles O F. Telecommunications and Space Debris: Adaptive Regulation Beyond Earth. Telecommun Policy 2023, 47, 102517. [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, N.; Tachibana, N. A tethered plate satellite as a sweeper of small space debris. Acta Astronaut 2021, 189, 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Witze, A. The quest to conquer earth's space junk problem. Nature 2018, 561, 24–26. [CrossRef]

- A. Nanjangud, P.C. Blacker, S. Bandyopadhyay, Y. Gao. Robotics and AI-Enabled On-Orbit Operations With Future Generation of Small Satellites. P Ieee 2018, 106, 429-439. [CrossRef]

- N. Inaba, M. Oda, M. Asano. Rescuing a Stranded Satellite in Space-Experimental Robotic Capture of Non-Cooperative Satellites. T Jpn Soc Aeronaut S 2006, 48, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- E. Papadopoulos, F. Aghili, O. Ma, R. Lampariello. Robotic Manipulation and Capture in Space: A Survey. Front Robot Ai 2021, 8, 686723. [CrossRef]

- T. Rybus. Obstacle avoidance in space robotics: Review of major challenges and proposed solutions. Prog Aerosp Sci 2018, 101, 31-48. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Hatch, J. E. Pennington, and J. B. Cobb. Dynamic simulation of lunar module docking with Apollo command module in lunar orbit. NASA Tech. Note TN D-3972, 1967, pp. 1–26.

- Uyama N, Fujii Y, Nagaoka K, et al. Experimental evaluation of contact-impact dynamics between a space robot with a compliant wrist and a free-flying object. International symposium on artificial intelligence, robotics and automation in space, Turin, Italy. 2012.

- Wei, Y., Yang, X., Xu, Z., Bai, X. Novel ground microgravity experiment system for a spacecraft-manipulator system based on suspension and air-bearing. Aerosp Sci Technol 2023, 141, 108587. [CrossRef]

- O. Ma and J. Wang. Model order reduction for impact-contact dynamics simulations of flexible manipulators. Robotica 2007, 25, 397–407. [CrossRef]

- A. Flores-Abad, O. Ma, K. Pham, S. Ulrich. A review of space robotics technologies for on-orbit servicing. Prog Aerosp Sci 2014, 68, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- A. Yaskevich. Real time math simulation of contact interaction during spacecraft docking and berthing. J. Mech. Eng. Autom 2014, 4, 1–15.

- Roe F D, Howard R T, Murphy L. Automated rendezvous and capture system development and simulation for NASA. Modeling, Simulation, and Calibration of Space-based Systems. SPIE 2004, 5420: 118-125.

- Mitchell, J. D., Cryan, S. P., Baker, K., Martin, T., Goode, R., Key, K. W., Chien, C. H. Integrated docking simulation and testing with the Johnson space center six-degree-of-freedom dynamic test system. In Proc. Space Technol. Appl. Int. Forum, 2008, pp. 709–716.

- Boge T , Ma O .Using advanced industrial robotics for spacecraft Rendezvous and Docking simulation. In 2011 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation, pp. 1-4.

- O. Ma, A. Flores-Abad, and T. Boge. Use of industrial robots for hardware-in-the-loop simulation of satellite rendezvous and docking. Acta Astronaut 2012, 81, 335–347. [CrossRef]

- Wei YQ, Yang X, Bai XL, Xu ZG. Hardware-in-the-loop based ground test system for space berthing and docking mechanism of small spacecraft. P I Mech Eng G-J Aer 2023, 237, 3486-3495. [CrossRef]

- Zebenay, M., Lampariello, R., Boge, T., Choukroun, D. A new contact dynamics model tool for hardware-in-the-loop docking simulation. 2012.

- Zebenay M, Boge T, Krenn R, et al. Analytical and experimental stability investigation of a hardware-in-the-loop satellite docking simulator. P I Mech Eng G-J Aer 2015, 229, 666-681. [CrossRef]

- Qi, C., Ren, A., Gao, F., Zhao, X., Wang, Q., Sun, Q. Compensation of velocity divergence caused by dynamic response for hardware-in-the-loop docking simulator. Ieee-Asme T Mech 2016, 22, 422-432. [CrossRef]

- Stefano M D, Balachandran R, Secchi C. A Passivity-Based Approach for Simulating Satellite Dynamics With Robots: Discrete-Time Integration and Time-Delay Compensation. Ieee T Robot 2020, 36, 189-203. [CrossRef]

- Rao, L. S., Rao, P. S., Chhabra, I. M., Kumar, L. S. Modeling and Compensation of Time-Delay Effects in HILS of Aerospace Systems. Iete Tech Rev 2022, 39, 375-388. [CrossRef]

- Osaki K, Konno A, Uchiyama M. Delay time compensation for a hybrid simulator. Adv Robotics 2010, 24, 1081-1098. [CrossRef]

- Abiko, S., Satake, Y., Jiang, X., Tsujita, T., Uchiyama, M. Delay time compensation based on coefficient of restitution for collision hybrid motion simulator. Adv Robotics 2014, 28, 1177-1188. [CrossRef]

- Khusainov, D. Y., Diblík, J., Růžičková, M., Lukáčová, J. Representation of a solution of the Cauchy problem for an oscillating system with pure delay. Nonlinear Oscil 2008, 11, 276-285. [CrossRef]

- Ricardo L G G, Lagomasino G L. Strong asymptotics of multi-level Hermite-Padé polynomials. J Math Anal Appl 2024, 531, 127801. [CrossRef]

- Đukić, D., Mutavdžić Đukić, R., Reichel, L., Spalević, M. Optimal averaged Padé-type approximants. Electron T Numer Ana 2023, 59, 145-156. [CrossRef]

- Motoyama Y, Yoshimi K, Otsuki J. Robust analytic continuation combining the advantages of the sparse modeling approach and the Padé approximation. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 035139. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K., Chaudhary, N. I., Cheema, K. M., Khan, Z. A., Raja, M. A. Z., Milyani, A. H., Alsulami, A. Design of nonlinear marine predator heuristics for hammerstein autoregressive exogenous system identification with key-term separation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2512. [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Perez, C., Serrano, A. A., Solís-Rosas, G., Martínez-Jiménez, A., Orozco-Cruz, R., Espinoza-Vázquez, A., Miralrio, A. A general use QSAR-ARX model to predict the corrosion inhibition efficiency of drugs in terms of quantum mechanical descriptors and experimental comparison for lidocaine. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 5086. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K., Chaudhary, N. I., Khan, Z. A., Cheema, K. M., Raja, M. A. Z., Shu, C. M. Novel knacks of chaotic maps with Archimedes optimization paradigm for nonlinear ARX model identification with key term separation. Chaos Soliton Fract 2023, 175, 114028. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q., Wang, M., Li, X., Chang, Y. Learning-based design optimization of second-order tracking differentiator with application to missile guidance law. Aerosp Sci Technol 2023, 137, 108302. [CrossRef]

- Park J H, Park T S, Kim S H. Asymptotically convergent higher-order switching differentiator. Mathematics 2020, 8, 185. [CrossRef]

- Feng H, Qian Y. A linear differentiator based on the extended dynamics approach. Ieee T Automat Contr 2022, 67, 6962-6967. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira T R, Estrada A, Fridman L M. Global and exact HOSM differentiator with dynamic gains for output-feedback sliding mode control. Automatica 2017, 81, 156-163. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).