Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

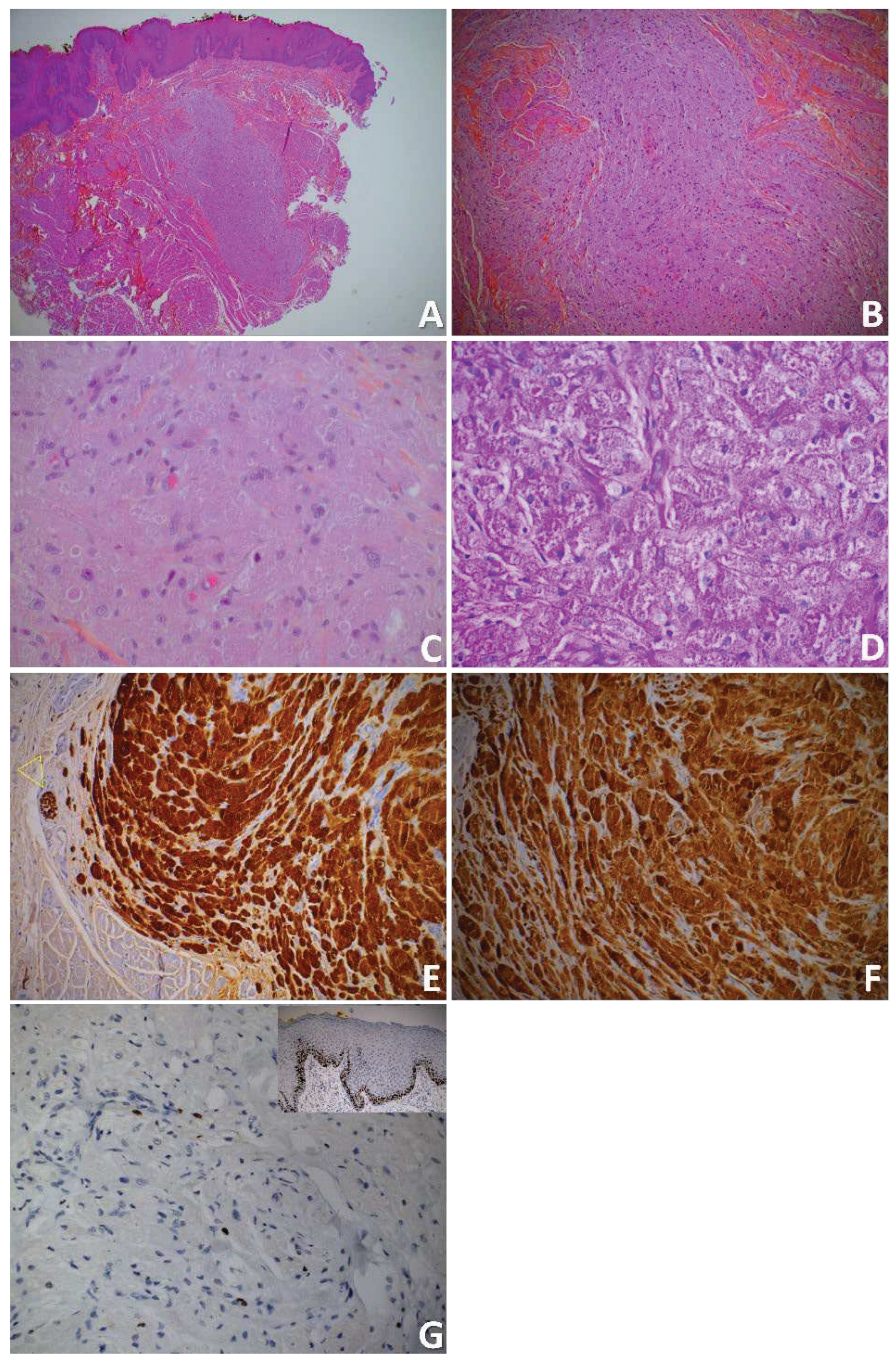

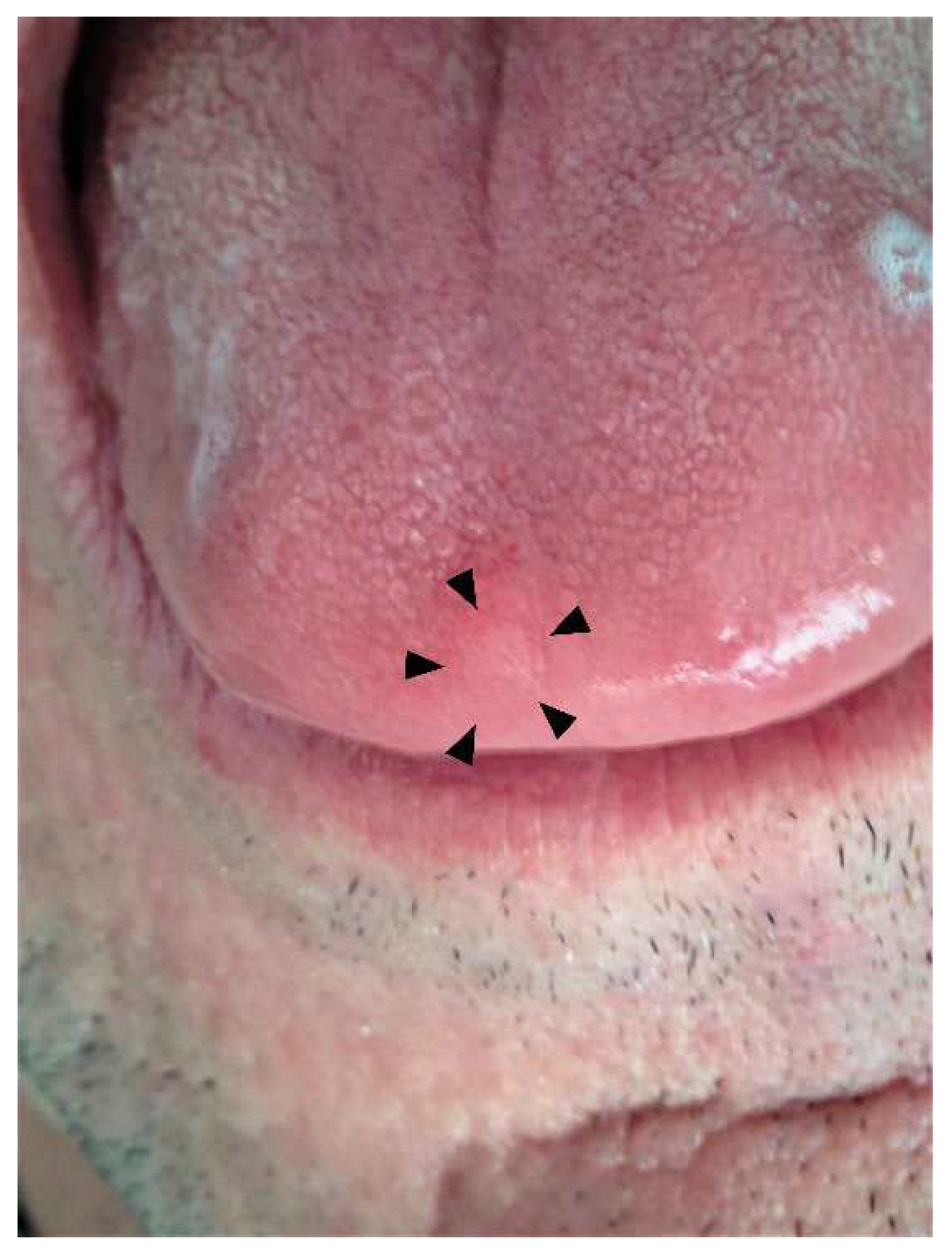

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendoza ILI de Ortega, K.L.; Trierveiler, M.; et al. Oral granular cell tumour: A multicentric study of 56 cases and a systematic review. Oral Dis 2020, 26, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Naggar, A.K.; Chan, J.K.C.; Grandis, J.R.; Takata, T.; Slootweg, P.J. (Eds.). (2017). WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. (4th edition). (Vol. 9). https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHO-Classification-Of-Head-And-Neck-Tumours-2017 (accessed 10 May 2023). 10 May.

- Abrikossoff, A. Uber myome, ausgehend von der quergestreiften willkurlichen Muskulatur. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med 1926, 260, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, T.; De Freitas Filho, S.A.J.; Muniz, L.-B.; De Faria, P.R.; Loyola, A.M.; Cardoso, S.V. Oral peripheral nerve sheath tumors: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases in a Brazilian population. J Clin Exp Dent 2017, 9, e1459–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manara, G.C.; De Panfilis, G.; Bacchi, A.B.; et al. Fine structure of granular cell tumor of Abrikosov. J Cutan Pathol 1981, 8, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Kawana, T.; Katoh, T.; Kozawa, Y.; Hayashi, I. Granular cell tumor of the tongue: an electron microscopical and immunohistochemical study. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent 1990, 32, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj, P.B.; Ongole, R.; Bhujanga-Rao, B.R. Granular cell tumor of the tongue in a 6-year-old girl--a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cirugia Bucal 2006, 11, E162–E164. [Google Scholar]

- Karakostas, P.; Matiakis, A.; Anagnostou, E.; Kolokotronis, A. Oral granular cell tumor: Report of case series and a brief review of the literature. Balk J Dent Med 2017, 21, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfin, L.E.; De Abreu Alves, F.; De Almeida, O.P.; Kowalski, L.P.; Da Cruz Perez, D.E. Multiple granular cell tumors of the tongue and parotid gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009, 107, e10–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamps, S.; Oyen, T.; Legius, E.; Vandenoord, J.; Stas, M. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg Off J Austrian Assoc Pediatr Surg Al Z Kinderchir 2013, 23, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dive, A.; Dhobley, A.; Fande, P.Z.; Dixit, S. Granular cell tumor of the tongue: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2013, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, E.; Rahman, N.; Webb, R. Case series: Two cases of an atypical presentation of oral granular cell tumour. Case Rep Med 2012, 2012, 159803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budiño-Carbonero, S.; Navarro-Vergara, P.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, J.; Modelo-Sánchez, A.; Torres-Garzón, L.; Rendón-Infante, J.I.; Fortis-Sánchez, E. Granular cell tumors: Review of the parameters determining possible malignancy. Med Oral Organo Of Soc Espanola Med Oral Acad Iberoam Patol Med Bucal 2003, 8, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano, E.; Favia, G.; Napoli, A.; Resta, L.; Ricco, R.; Viale, G.; Altini, M. Cellular heterogeneity of granular cell tumours: A clue to their nature? J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 2000, 29, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanburg-Smith, J.C.; Meis-Kindblom, J.M.; Fante, R.; Kindblom, L.G. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: Diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 1998, 22, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, I.; Cruz, J.; Lavernia, J.; Llombart-Bosch, A. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: The “Granular Cell Tumor” puzzle. Virchows Arch Int J Pathol 2016, 468, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, H.; Ahmed, Y.; Szpunar, S.; Kowalski, P. Malignant granular cell tumor: A look into the diagnostic criteria. Pathol Res Pract 2011, 207, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamiolakis, P.; Chrysomali, E.; Sklavounou-Andrikopoulou, A.; Nikitakis, N.G. Oral neural tumors: Clinicopathologic analysis of 157 cases and review of the literature. J Clin Exp Dent 2019, 11, e721–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarbashi-Moghadam, S.; Saebnoori, H.; Shamloo, N.; Barouj, M.D.; Saedi, S. Granular cell odontogenic tumor, an extremely rare case report. J Dent 2019, 20, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, Y.B.; Dodson, T.B. S-100 negative granular cell tumor (So-called primitive polypoid non-neural granular cell tumor) of the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol 2017, 11, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).