Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Physical and chemical properties

3. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and toxicological studies of CK

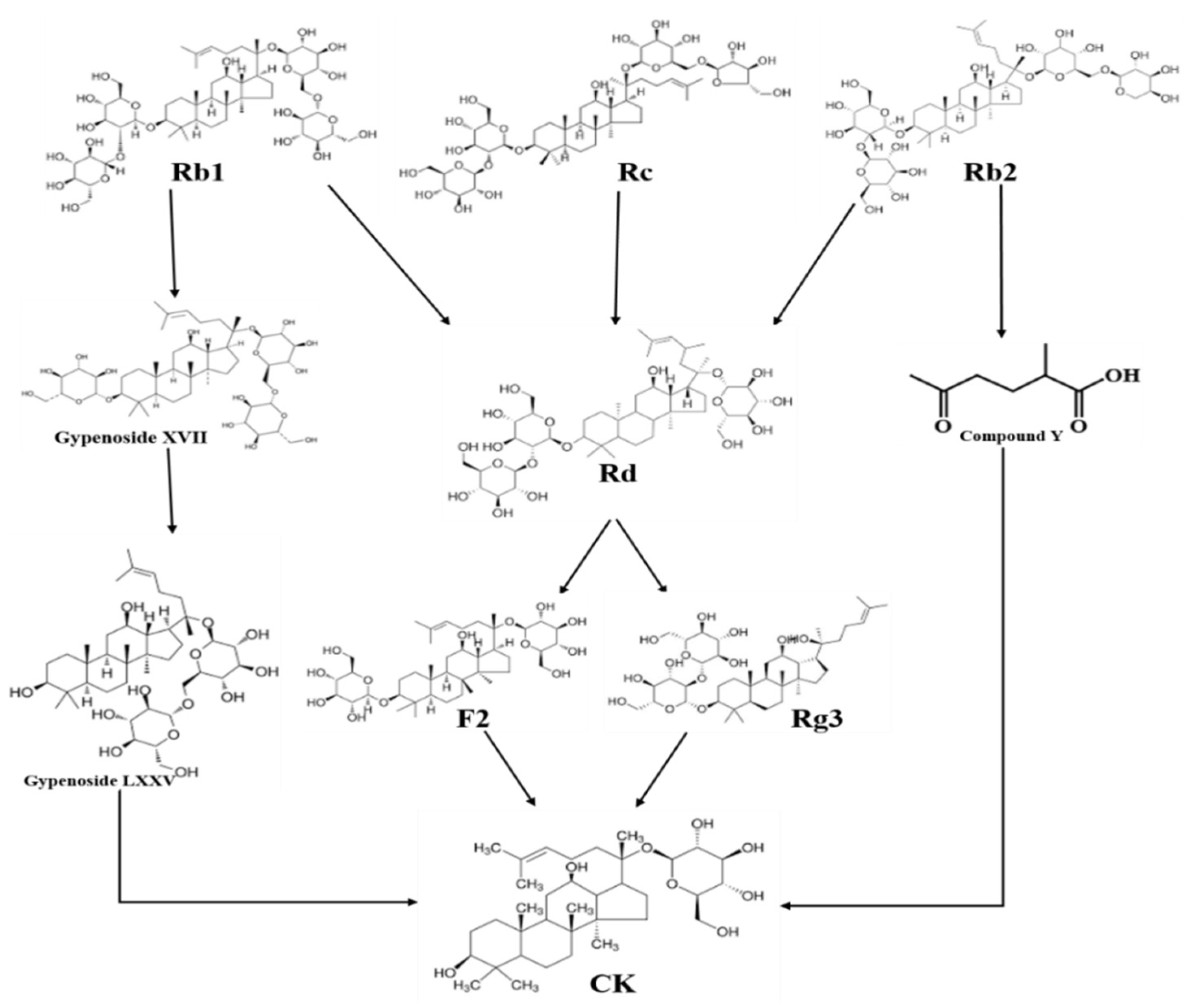

4. Biotransformation of CK

4.1. Enzymatically synthesis

4.2. Biotransformation of CK by human gut microbiota

5. Mechanism of CK against metabolic diseases

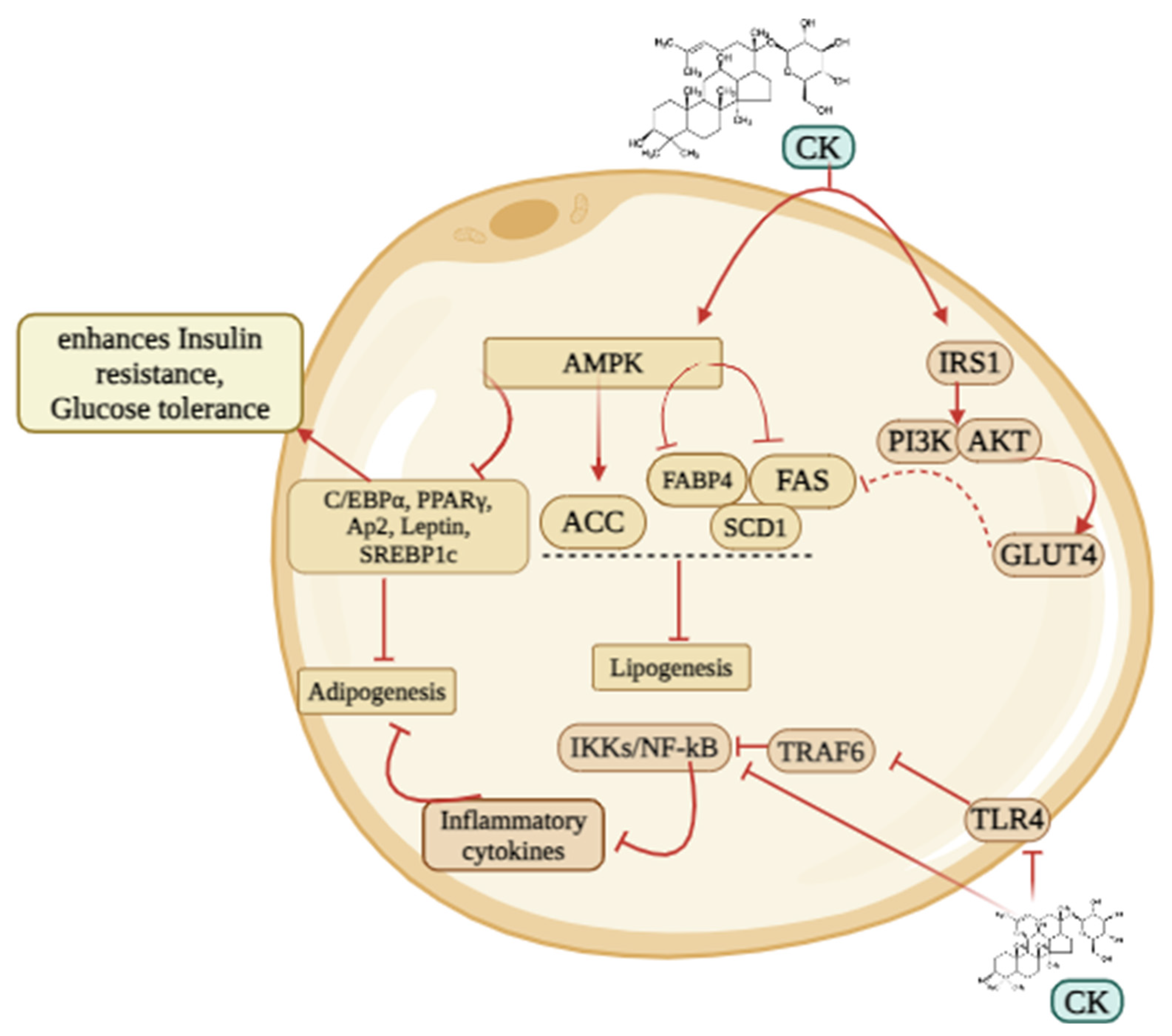

5.1. Obesity

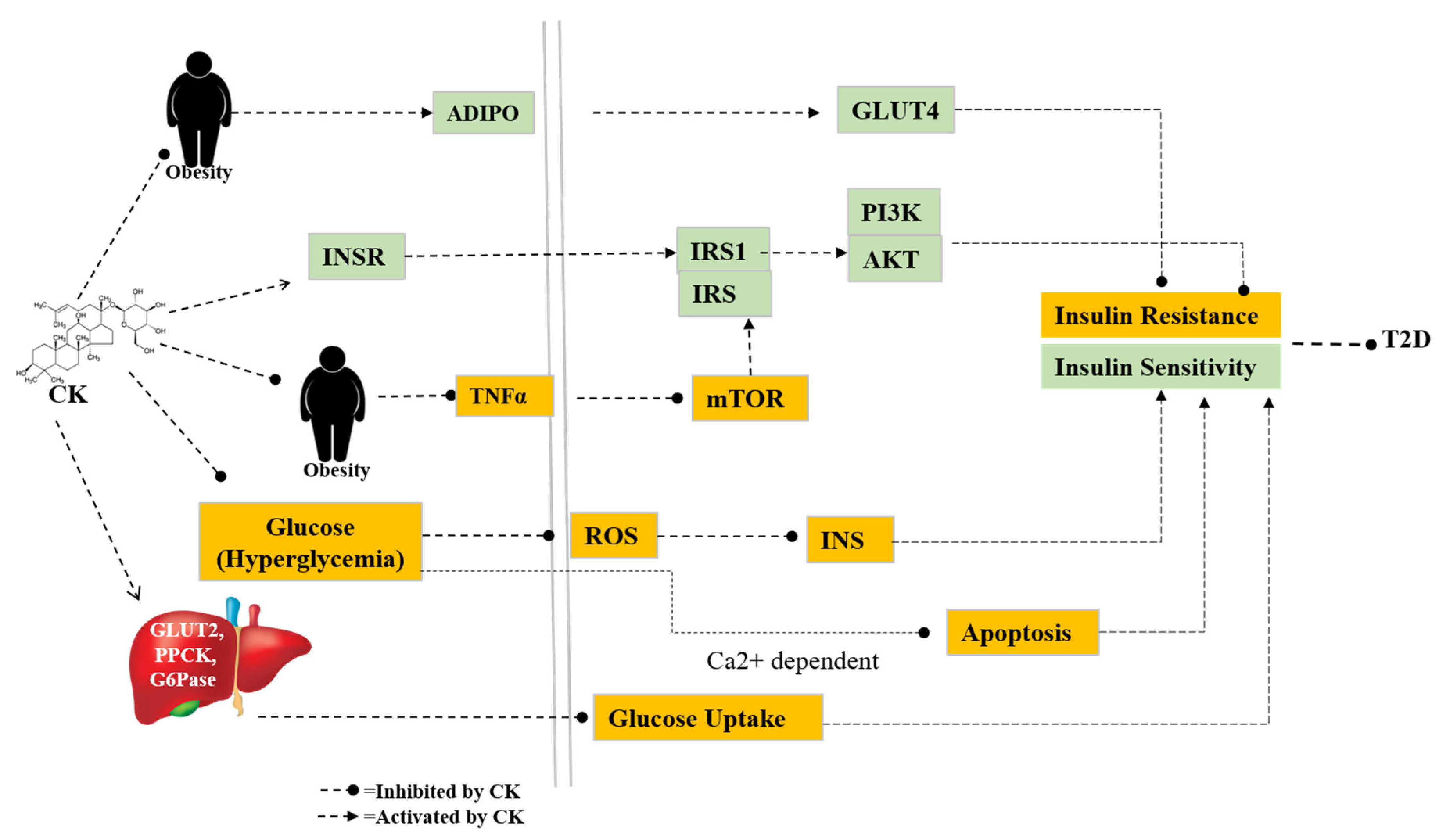

5.2. Diabetes and related complications

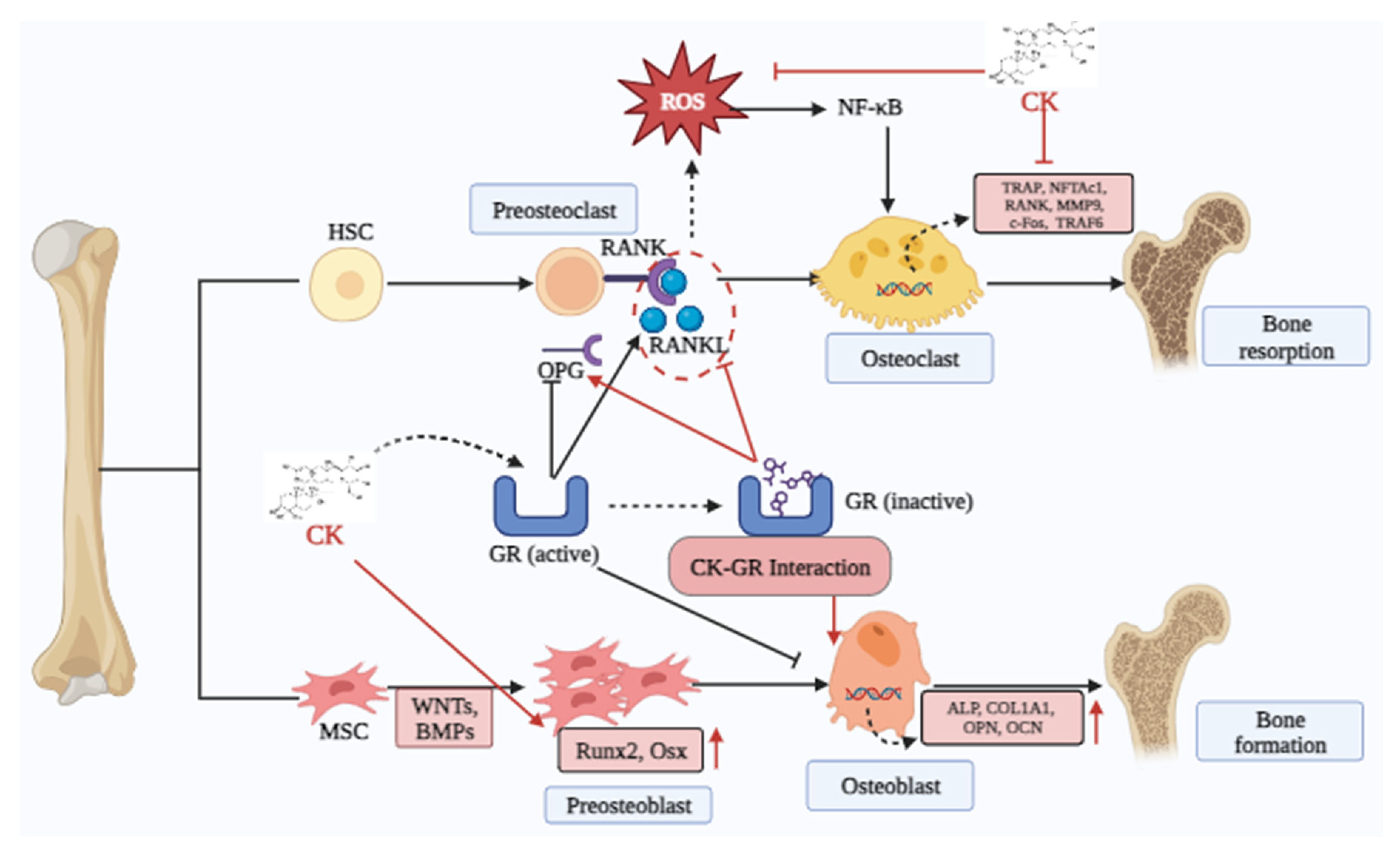

5.3. Osteoporosis

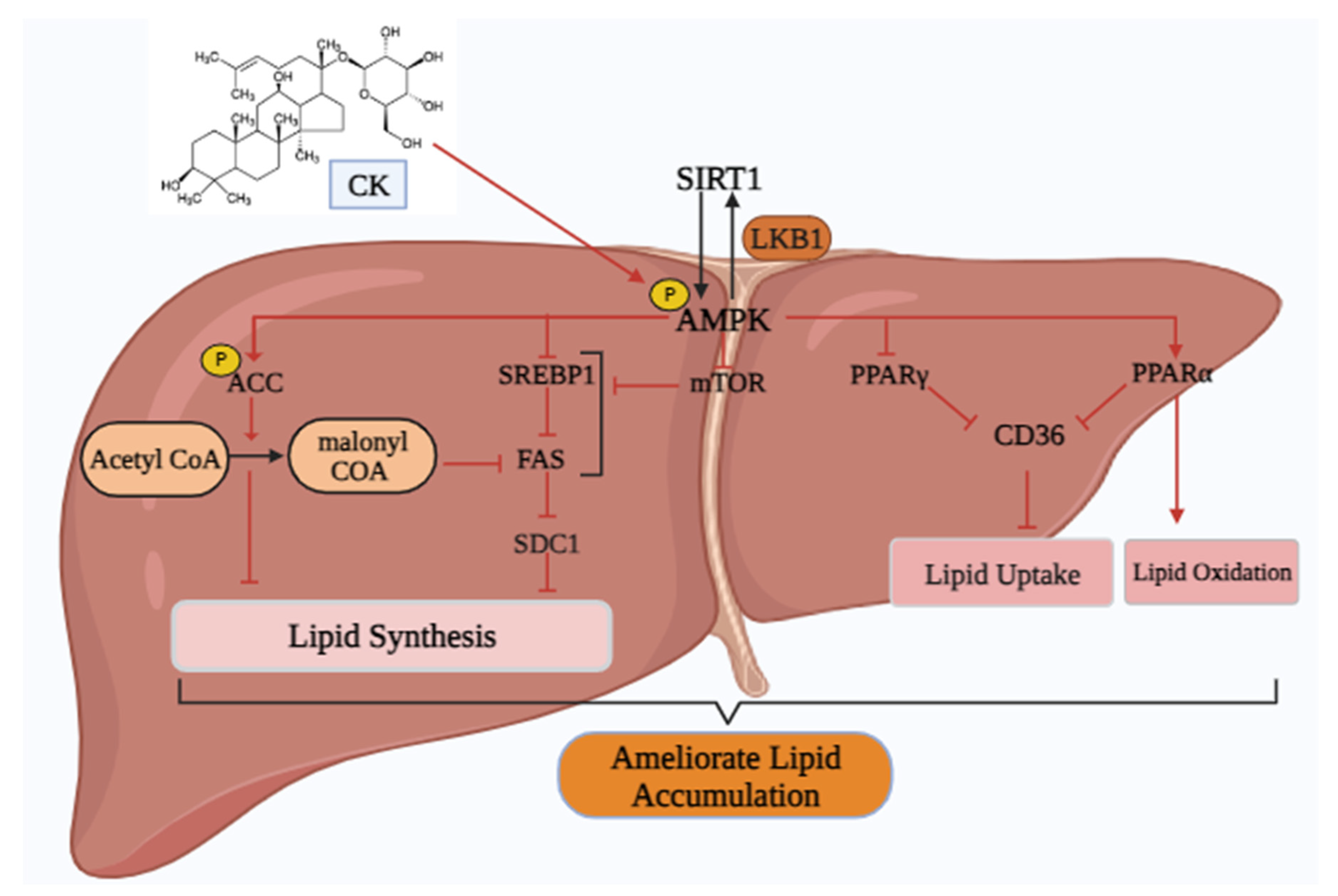

5.4. Non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

6. Mechanism of TP53 regulating pathway in metabolic diseases

7. Synthesis of CK analogues and their pharmacological activity

8. Discussion and future perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saklayen, M.G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Current hypertension reports 2018, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-L.; Lin, Z.-J.; Li, C.-C.; Lin, X.; Shan, S.-K.; Guo, B.; Zheng, M.-H.; Li, F.; Yuan, L.-Q.; Li, Z.-h. Epigenetic regulation in metabolic diseases: mechanisms and advances in clinical study. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A. Strengthening the International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020, 160, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, M.; Hill, M.A.; Cohen, P.; Sowers, J.R. Obesity, adipose tissue and vascular dysfunction. Circulation research 2021, 128, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Gaffo, A. Gout epidemiology and comorbidities. In Proceedings of the Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism, 2020; pp. S11-S16. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Perumalsamy, H.; Markus, J.; Balusamy, S.R.; Wang, C.; Ho Kang, S.; Lee, S.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Castro-Aceituno, V. Development of Lactobacillus kimchicus DCY51T-mediated gold nanoparticles for delivery of ginsenoside compound K: in vitro photothermal effects and apoptosis detection in cancer cells. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2019, 47, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed, M.N.; Ahn, J.C.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Rupa, E.J.; Akter, R.; Karim, M.R.; Jung, D.H.; Yang, D.U.; Yang, D.C.; Jung, S.K. Antioxidant Activity of Panax ginseng to Regulate ROS in Various Chronic Diseases. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Siddiqi, M.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Ahn, S.; Noh, H.-Y.; Kumar, N.S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yang, D.-C. Therapeutic potential of compound K as an IKK inhibitor with implications for osteoarthritis prevention: an in silico and in vitro study. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2016, 52, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhou, J.; Gu, Q.; Harindintwali, J.D.; Yu, X.; Liu, X. Combinatorial Enzymatic Catalysis for Bioproduction of Ginsenoside Compound K. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 3385–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.L.; Hanh, N.T.Y.; Quyen, M.L.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Lien, T.T.P.; Do, K.V. Compound K Production: Achievements and Perspectives. Life 2023, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.-D.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Ouyang, D.-S.; Yang, G.-P. A review of biotransformation and pharmacology of ginsenoside compound K. Fitoterapia 2015, 100, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, G.C.; Ko, S.K.; Sung, J.H.; Chung, S.H. Compound K Enhances Insulin Secretion with Beneficial Metabolic Effects in db/db Mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2007, 55, 10641–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Dong, J.; Ding, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Yao, F. Ginsenoside compound K inhibits obesity-induced insulin resistance by regulation of macrophage recruitment and polarization via activating PPARγ. Food Funct 2022, 13, 3561–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.C.; Oh, D.H.; Choi, M.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Ahn, K.J.; Chung, H.Y.; Lim, S.J.; Chung, S.H.; Jeong, I.K. Compound K attenuates glucose intolerance and hepatic steatosis through AMPK-dependent pathways in type 2 diabetic OLETF rats. Korean J Intern Med 2018, 33, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021, 18, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, E.A.; Ford, R.J.; Steinberg, G.R. AMPK as a Therapeutic Target for Treating Metabolic Diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiou, M. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ as a Target and Regulator of Epigenetic Mechanisms in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Yoon, M. Compound K, a novel ginsenoside metabolite, inhibits adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells: Involvement of angiogenesis and MMPs. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2012, 422, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, M.; Riscal, R.; Arena, G.; Linares, L.K.; Le Cam, L. Metabolic functions of the tumor suppressor p53: Implications in normal physiology, metabolic disorders, and cancer. Mol Metab 2020, 33, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, M.-H.; Jang, H.-M.; Im, W.-T.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.-H.; Jeon, G.J. A rare ginsenoside compound K (CK) induces apoptosis for breast cancer cells. Journal of Animal Reproduction and Biotechnology 2023, 38, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Ginsenosides: chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Advances in food and nutrition research 2008, 55, 1–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-M.; Kim, E.; Chun, S. Ginsenoside compound K induces ros-mediated apoptosis and autophagic inhibition in human neuroblastoma cells in vitro and in vivo. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, L. A narrative review of the pharmacology of ginsenoside compound K. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Sun, R.; Zhang, P.; Lv, J. Characterization of ginsenoside compound K metabolites in rat urine and feces by ultra-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Biomedical Chromatography 2019, 33, e4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Huang, J.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liao, J.; Ouyang, D. Food and sex-related impacts on the pharmacokinetics of a single-dose of ginsenoside compound K in healthy subjects. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2017, 8, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-K. Pharmacokinetics of ginsenoside Rb1 and its metabolite compound K after oral administration of Korean Red Ginseng extract. Journal of ginseng research 2013, 37, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liao, J.; Ouyang, D. Single-and multiple-dose trials to determine the pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and sex effect of oral ginsenoside compound K in healthy Chinese volunteers. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 8, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Kang, J.-W.; Song, Y.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, M.S.; Bak, Y.; Oh, D.-K.; Yoon, D.-Y. Compound K attenuates lipid accumulation through down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in 3T3-L1 cells. Journal of the Korean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry 2013, 56, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yang, H.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D.; Deng, J. Ginsenoside CK inhibits androgenetic alopecia by regulating Wnt/β-catenin and p53 signaling pathways in AGA mice. Food Frontiers 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Siddiqi, M.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Ahn, S.; Noh, H.-Y.; Kumar, N.S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yang, D.-C. Therapeutic potential of compound K as an IKK inhibitor with implications for osteoarthritis prevention: an in silico and in vitro study. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal 2016, 52, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Fan, D. Ginsenoside CK ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation via activating the LKB1/AMPK pathway in vitro and in vivo. Food & Function 2022, 13, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Yuan, H.D.; Chung, I.K.; Chung, S.H. Compound K, Intestinal Metabolite of Ginsenoside, Attenuates Hepatic Lipid Accumulation via AMPK Activation in Human Hepatoma Cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57, 1532–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Yang, Q.; Lan, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, Z.; Shi, X.; Li, J.; Kan, M.; Qu, X. Ginsenoside compound K ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease in HT22 cells by adjusting energy metabolism. Molecular Biology Reports 2019, 46, 5323–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zeng, X.; Rao, T.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ouyang, D.; Chen, L. Evaluating the protective effects of individual or combined ginsenoside compound K and the downregulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase expression against sodium valproate-induced liver cell damage. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2021, 422, 115555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kang, E.H.; Lee, E.Y.; Gong, H.S.; Kang, H.S.; Shin, K.; Lee, E.B.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, Y.J. Joint-protective effects of compound K, a major ginsenoside metabolite, in rheumatoid arthritis: in vitro evidence. Rheumatology International 2013, 33, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Li, W.; Xiao, D.; Wei, S.; Cui, W.; Chen, W.; Hu, Y.; Bi, X.; Kim, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Compound K, a final intestinal metabolite of ginsenosides, enhances insulin secretion in MIN6 pancreatic β-cells by upregulation of GLUT2. Fitoterapia 2013, 87, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.K.-M.; Kwok, H.-H.; Poon, P.-Y.; Lau, C.-C.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Tai, W.C.-S.; Hsiao, W.W.-L.; Mak, N.-K.; Yue, P.Y.-K.; Wong, R.N.-S. Ginsenoside compound K induces apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via activation of apoptosis-inducing factor. Chinese medicine 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boopathi, V.; Nahar, J.; Murugesan, M.; Subramaniyam, S.; Kong, B.M.; Choi, S.-K.; Lee, C.-S.; Ling, L.; Yang, D.U.; Yang, D.C. In silico and in vitro inhibition of host-based viral entry targets and cytokine storm in COVID-19 by ginsenoside compound K. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.A.; Piao, M.J.; Kim, K.C.; Zheng, J.; Yao, C.W.; Cha, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, D.H.; Bae, S.C.; Hyun, J.W. Compound K, a metabolite of ginseng saponin, inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth and induces apoptosis through inhibition of histone deacetylase activity. International Journal of Oncology 2013, 43, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; You, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Preclinical safety of ginsenoside compound K: Acute, and 26-week oral toxicity studies in mice and rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 131, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Ding, M.; Xin, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Genotoxicity and subchronic toxicological study of a novel ginsenoside derivative 25-OCH3-PPD in beagle dogs. Journal of Ginseng Research 2019, 43, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Siddiqi, M.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Ahn, S.; Noh, H.Y.; Kumar, N.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, D.C. Therapeutic potential of compound K as an IKK inhibitor with implications for osteoarthritis prevention: an in silico and in vitro study. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2016, 52, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-J.; Ko, W.-G.; Kim, J.-H.; Sung, J.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Moon, C.-K.; Lee, B.-H. Induction of apoptosis by a novel intestinal metabolite of ginseng saponin via cytochrome c-mediated activation of caspase-3 protease. Biochemical Pharmacology 2000, 60, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.A.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, Y.W.; Kim, W.T.; Chung, H.S.; Choo, M.K.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.S.; Shim, M.J. Induction of apoptosis by ginseng saponin metabolite in U937 human monocytic leukemia cells. Journal of food biochemistry 2005, 29, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Lin, J.; Sun, L.; Sun, X.; Cho, S. Repeated-dose 26-week oral toxicity study of ginsenoside compound K in Beagle dogs. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 248, 112323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, Y.-S.; Park, K.-K.; Lee, J.-M.; Chun, K.-S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.K.; Kwon, H.; Surh, Y.-J. Antioxidant and anti-tumor promoting activities of the methanol extract of heat-processed ginseng. Cancer Letters 2000, 150, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Fu, L.; Gao, J.; Du, X.; Bi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Tai, G. Highly selective biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to Rd by the phytopathogenic fungus Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Fulvia fulva). Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2009, 36, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhou, X.-W.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.-W.; Feng, M.-Q.; Zhou, P. Purification and properties of a novel ${\beta} $-glucosidase, hydrolyzing ginsenoside Rb1 to CK, from Paecilomyces Bainier. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2008, 18, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.-S.; Cui, C.-H.; Lee, H.-G.; Wang, L.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, S.-T.; Jin, F.; Yu, H.; Chin, Y.-W.; Lee, H.-K. Identification and characterization of a novel Terrabacter ginsenosidimutans sp. nov. β-glucosidase that transforms ginsenoside Rb1 into the rare gypenosides XVII and LXXV. Applied and environmental microbiology 2010, 76, 5827–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.-L.; Dong, W.-W.; Wu, S.; Jiang, J.; Yang, D.-C.; Li, D.; Quan, L.-H. Biotransformation of gypenoside XVII to compound K by a recombinant β-glucosidase. Biotechnology letters 2016, 38, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, K.-H.; Son, J.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Oh, D.-K. Ginsenoside compound K production from ginseng root extract by a thermostable β-glycosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 2009, 73, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.-H.; Yeom, S.-J.; Park, C.-S.; Lee, K.-W.; Oh, D.-K. Production of aglycon protopanaxadiol via compound K by a thermostable β-glycosidase from Pyrococcus furiosu s. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2011, 89, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, C.; Min, J.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, D.C. Enzymatic transformation of the major ginsenoside Rb2 to minor compound Y and compound K by a ginsenoside-hydrolyzing β-glycosidase from Microbacterium esteraromaticum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 39, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Yang, F.; Tian, F.; Liu, X.; Fan, D.; Wu, Z. Immobilized β-glucosidase on Cu(PTA) for the green production of rare ginsenosides CK. Process Biochemistry 2023, 133, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Tian, D.; Fan, D.; Ma, X.; Wu, Z. Co-immobilized β-glucosidase and snailase in green synthesized Zn-BTC for ginsenoside CK biocatalysis. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2022, 188, 108677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, R.; Tian, F.; Liu, X.; Fan, D.; Wu, Z. Construction of a hollow MOF with high sedimentation performance and co-immobilization of multiple-enzymes for preparing rare ginsenoside CK. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 8, 2804–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.N.A.; Son, J.-S.; Awais, M.; Ko, J.-H.; Yang, D.C.; Jung, S.-K. β-Glucosidase and Its Application in Bioconversion of Ginsenosides in Panax ginseng. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhu, C.; Shi, J.; Fan, D.; Deng, J.; Fu, R.; Huang, R.; Fan, C. High efficiency production of ginsenoside compound K by catalyzing ginsenoside Rb1 using snailase. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2018, 26, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Shin, K.-C.; Oh, D.-K. An L213A variant of β-glycosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus with increased α-L-arabinofuranosidase activity converts ginsenoside Rc to compound K. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0191018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-S.; Yoo, M.-H.; Noh, K.-H.; Oh, D.-K. Biotransformation of ginsenosides by hydrolyzing the sugar moieties of ginsenosides using microbial glycosidases. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2010, 87, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.-H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, C.; Min, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yang, D.-C. Enzymatic transformation of the major ginsenoside Rb2 to minor compound Y and compound K by a ginsenoside-hydrolyzing β-glycosidase from Microbacterium esteraromaticum. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2012, 39, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wu, S.-q.; Zhao, C.-a.; Yin, C.-r. Microbial conversion of major ginsenosides in ginseng total saponins by Platycodon grandiflorum endophytes. Journal of Ginseng Research 2016, 40, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, B.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, B.; Spranger, M.I.; Zhao, Y. Transformation of bioactive compounds by Fusarium sacchari fungus isolated from the soil-cultivated ginseng. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2007, 55, 9373–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Li, G.H.; Choi, K.-T.; Yang, D.-C. Microbial transformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to compound K by Lactobacillus paralimentarius. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2013, 29, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-Q.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, Y.-J.; Yang, D.-C. Conversion of major ginsenoside Rb 1 to ginsenoside F 2 by Caulobacter leidyia. Biotechnology letters 2006, 28, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, H.; Sung, J.-H.; Matsumiya, S.; Uchiyama, M. Main ginseng saponin metabolites formed by intestinal bacteria. Planta medica 1996, 62, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-A.; Jung, I.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Ahn, Y.-T.; Huh, C.-S.; Kim, D.-H. Comparative analysis of the gut microbiota in people with different levels of ginsenoside Rb1 degradation to compound K. PloS one 2013, 8, e62409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Feng, M.-Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhou, P. Studies on the preparation, crystal structure and bioactivity of ginsenoside compound K. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yan, Q.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, X.C.; Zhou, P. Biotransformation of Panax notoginseng saponins into ginsenoside compound K production by Paecilomyces bainier sp. 229. Journal of applied microbiology 2008, 104, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Sun, C.; Zheng, P. Screening of plant pathogenic fungi by ginsenoside compound K production. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi= Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi= China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 2011, 36, 1596–1598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-T.; Yang, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, Z.-Q.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Huang, H.-L.; Wu, L.-J.; Guo, D.-A. Microbial transformation of ginsenoside Rb 1 by Acremonium strictum. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2008, 77, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, H.; Ji, G.-E. Transformation of ginsenosides Rb1 and Re from Panax ginseng by food microorganisms. Biotechnology letters 2005, 27, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Yang, D.U.; Arunkumar, L.; Han, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Arif, M.H.; Li, J.F.; Huo, Y.; Kang, J.P.; Hoang, V.A.; et al. Cumulative Production of Bioactive Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, and CK from Fermented Black Ginseng Using Novel Aspergillus niger KHNT-1 Strain Isolated from Korean Traditional Food. Processes 2021, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.-H.; Piao, J.-Y.; Min, J.-W.; Yang, D.-U.; Lee, H.N.; Yang, D.C. Bioconversion of ginsenoside Rb1 into compound K by Leuconostoc citreum LH1 isolated from kimchi. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2011, 42, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Fan, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, G.; Yue, J.; Zhou, Z. Production of bioactive ginsenoside compound K in metabolically engineered yeast. Cell research 2014, 24, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, T.; Hu, C.; Li, W.; Meng, Y.; Li, H.; Song, C.; He, C.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, Y. Ginsenoside compound K protects against obesity through pharmacological targeting of glucocorticoid receptor to activate lipophagy and lipid metabolism. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Dong, J.; Xu, J.; Qiu, Z.; Yao, F. Ginsenoside CK inhibits obese insulin resistance by activating PPARγ to interfere with macrophage activation. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.-M.; Chun, S. Ginsenoside CK Inhibits the Early Stage of Adipogenesis via the AMPK, MAPK, and AKT Signaling Pathways. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Gu, J.; Meng, Z.-j.; Zhao, L.-C.; Zheng, Y.-n.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.-L. Hypoglycemic effect of protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides and compound K on Type 2 diabetes mice induced by high-fat diet combining with streptozotocin via suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ren, D.; Li, J.; Yuan, G.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Han, X.; Du, P.; An, L. Effects of compound K on hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fitoterapia 2014, 95, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Han, E.J.; Sung, J.H.; Chung, S.H. Anti-diabetic effects of compound K versus metformin versus compound K-metformin combination therapy in diabetic db/db mice. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2007, 30, 2196–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Wei, L.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. Protective effect of ginsenoside metabolite compound K against diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-κB/p38 signaling pathway in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. International Immunopharmacology 2018, 63, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Oh, H.; Abd El-Aty, A.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Jeong, J.H.; Jung, T.W. Therapeutic potential of ginsenoside compound K in managing tenocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix damage in diabetic tendinopathy. Tissue and Cell 2024, 86, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Gao, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Zou, H.; Zhao, G. Ginsenoside compound-K attenuates OVX-induced osteoporosis via the suppression of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and oxidative stress. Natural Products and Bioprospecting 2023, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Gu, S.; Zhou, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zou, H.; Zhao, G.; Gao, Z.; Xu, L. Ginsenoside compound K enhances fracture healing via promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 855393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-J.; Liu, W.-J.; Wen, M.-L.; Liang, H.; Wu, S.-M.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Dong, X.-Q.; Li, M.-G.; Bian, L.; et al. Ameliorative effects of Compound K and ginsenoside Rh1 on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 41144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Lee, K.T.; Iseli, T.J.; Hoy, A.J.; George, J.; Grewal, T.; Roufogalis, B.D. Compound K modulates fatty acid-induced lipid droplet formation and expression of proteins involved in lipid metabolism in hepatocytes. Liver International 2013, 33, 1583–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Han, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J. Compound K, a metabolite of ginseng saponin, induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the mitochondria-mediated caspase-dependent pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med 2017, 10, 11146–11156. [Google Scholar]

- Awais, M.; Akter, R.; Boopathi, V.; Ahn, J.C.; Lee, J.H.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Kwak, G.-Y.; Rauf, M.; Yang, D.C.; Lee, G.S. Discrimination of Dendropanax morbifera via HPLC fingerprinting and SNP analysis and its impact on obesity by modulating adipogenesis-and thermogenesis-related genes. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, G.; Pandeya, P.R.; Lamichhane, R.; Rhee, S.-j.; Devkota, H.P.; Jung, H.-J. Anti-obesity potential of ponciri fructus: effects of extracts, fractions and compounds on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Molecules 2022, 27, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Peng, D. The exchangeable apolipoproteins in lipid metabolism and obesity. Clinica Chimica Acta 2020, 503, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sereday, M.S.; Gonzalez, C.; Giorgini, D.; De Loredo, L.; Braguinsky, J.; Cobeñas, C.; Libman, C.; Tesone, C. Prevalence of diabetes, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia in the central area of Argentina. Diabetes & Metabolism 2004, 30, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, H.; Peng, J. GPR120: a critical role in adipogenesis, inflammation, and energy metabolism in adipose tissue. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuryłowicz, A.; Puzianowska-Kuźnicka, M. Induction of Adipose Tissue Browning as a Strategy to Combat Obesity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Dong, J.; Ding, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Yao, F. Ginsenoside compound K inhibits obesity-induced insulin resistance by regulation of macrophage recruitment and polarization via activating PPARγ. Food & Function 2022, 13, 3561–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, S.; Suzuki, K.; Ruhee, R.T. A brief overview of oxidative stress in adipose tissue with a therapeutic approach to taking antioxidant supplements. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, N.; Alzahrani, A.R.; Ibrahim, I.A.A.; Shahid, I.; Alanazi, I.M.; Falemban, A.H.; Imam, M.T.; Mohsin, N.; Azlina, M.F.N.; Arulselvan, P. Therapeutic strategy of biological macromolecules based natural bioactive compounds of diabetes mellitus and future perspectives: A systemic review. Heliyon 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Yao, F.; Lixiang, A.; Lan, X.; Guan, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Ginsenoside Compound K suppresses the hepatic gluconeogenesis via activating adenosine-5′ monophosphate kinase: A study in vitro and in vivo. Life sciences 2015, 139, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G. Chronic tendon pathology: molecular basis and therapeutic implications. Expert reviews in molecular medicine 2005, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzmann, M.N.; Ofotokun, I. Physiological and pathophysiological bone turnover—role of the immune system. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2016, 12, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, V.; Haffner-Luntzer, M. Interaction between bone and immune cells: Implications for postmenopausal osteoporosis. In Proceedings of the Seminars in cell & developmental biology; 2022; pp. 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavone, V.; Testa, G.; Giardina, S.M.C.; Vescio, A.; Restivo, D.A.; Sessa, G. Pharmacological Therapy of Osteoporosis: A Systematic Current Review of Literature. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Xie, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, F. Ginsenoside compound K- a potential drug for rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacological Research 2021, 166, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kang, E.H.; Lee, E.Y.; Gong, H.S.; Kang, H.S.; Shin, K.; Lee, E.B.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, Y.J. Joint-protective effects of compound K, a major ginsenoside metabolite, in rheumatoid arthritis: in vitro evidence. Rheumatology International 2013, 33, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.M.; Brancati, F.L.; Diehl, A.M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Wang, G.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Dai, Y. Therapeutic potential of alkaloid extract from Codonopsis Radix in alleviating hepatic lipid accumulation: insights into mitochondrial energy metabolism and endoplasmic reticulum stress regulation in NAFLD mice. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines 2023, 21, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.-T.; Su, H.-Y.; An, W. Glycosyltransferases and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2016, 22, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Wong, R.; Newberry, C.; Yeung, M.; Peña, J.M.; Sharaiha, R.Z. Multidisciplinary Clinic Models: A Paradigm of Care for Management of NAFLD. Hepatology 2021, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, Y.; Wu, L.; Peng, J. Natural products in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Novel lead discovery for drug development. Pharmacological Research 2023, 196, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Li, D.; Fan, S.; Tao, F.; Yu, Y.; Lu, W.; Chen, Q.; Yuan, A.; Wu, J.; Zhao, G. Long-term and liver-selected ginsenoside C–K nanoparticles retard NAFLD progression by restoring lipid homeostasis. Biomaterials 2023, 301, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Zeng, X.; Liao, J.; Ouyang, D. Ginsenoside compound K alleviates sodium valproate-induced hepatotoxicity in rats via antioxidant effect, regulation of peroxisome pathway and iron homeostasis. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2020, 386, 114829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J.; Oren, M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nature reviews cancer 2009, 9, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, C.P.; Murphy, M.E. The role of the p53 tumor suppressor in metabolism and diabetes. J Endocrinol 2016, 231, R61–r75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamino, T.; Orimo, M.; Shimizu, I.; Kunieda, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Ito, T.; Nojima, A.; Nabetani, A.; Oike, Y.; Matsubara, H. A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nature medicine 2009, 15, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Lee, J.W.; Gao, B.; Jung, M.H. Synergistic activation of JNK/SAPK induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ: apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells via the p53 and ROS pathway. Cellular signalling 2005, 17, 1516–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Tang, W.; Man, Y.; Wang, S.; Xi, J.; Li, J. NADPH oxidase 2-derived reactive oxygen species mediate FFAs-induced dysfunction and apoptosis of β-cells via JNK, p38 MAPK and p53 pathways. PloS one 2010, 5, e15726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwezdaryk, K.; Sullivan, D.; Saifudeen, Z. The p53/Adipose-Tissue/Cancer Nexus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.; Shackel, N.; Gorrell, M.; McLennan, S.; Twigg, S. Diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pathogenic duo. Endocrine reviews 2013, 34, 84–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahagi, N.; Shimano, H.; Matsuzaka, T.; Sekiya, M.; Najima, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Okazaki, H.; Tamura, Y.; Iizuka, Y.; Inoue, N. p53 involvement in the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 20571–20575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derdak, Z.; Lang, C.H.; Villegas, K.A.; Tong, M.; Mark, N.M.; de la Monte, S.M.; Wands, J.R. Activation of p53 enhances apoptosis and insulin resistance in a rat model of alcoholic liver disease. Journal of hepatology 2011, 54, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdak, Z.; Villegas, K.A.; Harb, R.; Wu, A.M.; Sousa, A.; Wands, J.R. Inhibition of p53 attenuates steatosis and liver injury in a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of hepatology 2013, 58, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Teratani, T.; Suzuki, T.; Oshikawa, T.; Yokoyama, H.; Shimamura, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Mataki, N.; Irie, R.; Minamino, T. p53/p66Shc-mediated signaling contributes to the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in humans and mice. Journal of hepatology 2012, 57, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasiuk, A.; Dzieciol, J.; Panasiuk, B.; Prokopowicz, D. Expression of p53, Bax and Bcl-2 proteins in hepatocytes in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 2006, 12, 6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.C. ALLEY PROOF. Med Sci Monit 2024, 30, e942899. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Ding, N.; Li, Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of Ginsenoside Compound K analogues as a novel class of anti-asthmatic agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2019, 29, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, L.; Jia, Y.; Li, X. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Ginsenoside Compound K Derivatives as a Novel Class of LXRα Activator. Molecules 2017, 22, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Xue, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y. Octyl ester of ginsenoside compound K as novel anti-hepatoma compound: Synthesis and evaluation on murine H22 cells in vitro and in vivo. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2018, 91, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.-M.; Hu, J.-N.; Ye, H.; Luo, T.; Liu, X.-R.; Li, H.-Y.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y.-N.; Deng, Z.-Y. Absorption mechanism of ginsenoside compound K and its butyl and octyl ester prodrugs in Caco-2 cells. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2012, 60, 10278–10284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, M.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Boopathi, V.; Kong, B.M.; Choi, S.-K.; Lee, C.-S.; Yang, D.C.; Kang, S.C.; Thambi, T. Production of Minor Ginsenoside CK from Major Ginsenosides by Biotransformation and Its Advances in Targeted Delivery to Tumor Tissues Using Nanoformulations. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, S.; Siahi-Shadbad, M.; Adibkia, K.; Barzegar-Jalali, M. Recent advances in improving oral drug bioavailability by cocrystals. Bioimpacts 2018, 8, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Compound K |

|---|---|

| Alias | 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol |

| CAS number | 39262-14-1 |

| Pubchem CID | 9852086 |

| Compound type | tetra-cyclic tri-terpenoid |

| Molecular formula | C36H62O8 |

| Molecular weight | 622.9 g/mol |

| Form | powder |

| color | White |

| Solubility | DMF: 10 mg/ml; DMSO: 10 mg/ml; DMSO: PBS (pH 7.2) (1:1): 0.5 mg/ml |

| Density | 1.19 |

| pka | 12.94±0.70(Predicted) |

| Melting point | 181~183℃ |

| Boiling point | 723.1±60.0 °C |

| LogP | 5.500 |

| Stability | Hygroscopic |

| Study model | Concentrations | Method of detection | Duration of experiment | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell lines | (0, 10, 20, 30, 40 µM) | MTS assay | 24 h | A high dose of CK (40 µM) did not affect cell viability | [29] |

| HaCaT keratinocytes cells | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, and 10.0 μM |

MTT assay | 24 h | The survival of HaCaT cells was not significantly affected by CK doses below 10 μM. | [30] |

| MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cell line | 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 μM | MTT assay | 48h | CK at various doses did not exhibit any appreciable toxicity. | [43] |

| HepG2 | 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 μM |

MTT assay | 24 h | As ginsenoside CK concentration increased to 30 μM, notable cytotoxic effects were seen. | [32] |

| HepG2 | 5−40 μM | CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit | 24h | Up to 40 μM doses, CK did not exhibit any cellular toxicity. | [33] |

| HT22 mouse hippocampal neuron cell |

2.5, 5, and 10 μM | MTT assay | 24 h | Ginsenoside CK can increase the survival of HT22 cells. | [34] |

| L02 Human liver cell line | 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 μM |

MTT assay | 24 h | The viability of the L02 cells appeared dramatically after treatment with CK at dosages of 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM. | [35] |

| RA-FLS and Raw 264.7 | 0.1, 0.5, 2.5, and 5 µM | MTT assay | 48 h | The ability to survive RA-FLS and RAW264.7 cells was not significantly impacted by CK at doses of ≤5µM. | [36] |

| MIN6 cell line | 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 μM | MTT assay | 24 h | At 16 μM CK showed little toxicity on MIN6 cell | [37] |

| Hk-1 Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma cells, | 1–20μM | MTT assay | 24 h | The IC50 of CK was 11.5 on HK-1 cells | [38] |

| A549 lung cancer cells, MCF7 breast cancer cells, Caco-2 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, and normal RAW 264.7 cells |

0,3.125,6.25,12.5, 25 μg/mL |

MTT assay | 24 h | At 12.5 μg/mL concentration, CK showed considerable cytotoxic effect on A549 cells, MCF-7 cells, and Caco-2 cells growth. However, at 6.25 μg/mL Raw 264.7 cells showed less toxicitry. | [39] |

| HT-29 Human colon cancer cells | 8, 16, 32 and 64 μmol/l | MTT assay | 24 h | CK inhibited the growth of HT-29 cells in a dose-dependent manner. | [40] |

| HL-60 human myeloid leukemia cell line |

10, 20, 30, 50 μM | MTT assay | 72–96 h | 24.3 μM was needed to achieve 50% growth inhibition (IC50) at 96 hours. | [44] |

| U937, Jurkat, CEM-CM3, Molt4, and H9 leukemia cell lines | Did not mention | MTT assay | 96 h | The IC50 values of Compound K were as follows: 20μg/mL for U937, 26μg/mL for Jurkat, 36μg/mL for CEM-CM3, μg/mL for Molt 4, and 64μg/mL for H9. | [45] |

| Rat and mice | 8 and 10 mg/kg Respectively |

Acute oral repeated dose | 26-week | There were no indications of unusual clinical harm or death after 14 days. There were a few notable variations observed in this shift at weeks 9, 10, 12, 15, 17, 21–24, and 26. As a result, CK had a minimally negative impact on the animal’s body weight. |

[41] |

| Beagle dogs | 4, 12, or 36 mg/kg | oral doses | 26 week | No obvious toxicity was shown by the animals in the 4 and 12 mg/kg groups. The 36 mg/kg group showed elevated plasma enzyme levels, localized liver necrosis, and a decrease in body weight. |

[46] |

| Enzymes | Transformation pathway | Optimum condition | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-glu from Paecilomyces Bainier sp. 229 | Rb1→Rd→F2→CK | PH=3.5, Temp=55°C, Time=48h | 84.3% ginsenoside Rb1 was converted to CK | [49] |

| β-glu from Terrabacter ginsenosidimutans | Rb1→gypenoside XVII→ gypenoside LXXV→CK |

pH 7.0 37°C |

Complete conversion of CK from Rb1 via intermediate metabolites gypenosides XVII and LXXV. | [50] |

| β-glu from Lactobacillus brevis | Rb1→gypenoside XVII→ gypenoside LXXV→CK |

pH =6.0 Temp=30°C Time=6 h |

89% molar conversion | [51] |

| β-glycosidase from S. solfataricus | Rb1/Rb2→Rd→F2→CK Rc →compound Mc → CK |

PH=5.5, Temp=85°C, Time=12h | Although good specificity, the conversion rate is low. | [52] |

| β-glucosidase from Pyrococcus furiosus | Rb1/Rb2→Rd→F2→CK | PH=5.5, Temp=95°C, Time=6h | After five hours, aglycone PPD was produced by hydrolyzing the CK. | [53] |

| β-glucosidase from Microbacterium esteraromaticum | Rb2→Compound Y→CK | PH=7, Temp=40°C, | Ginsenoside Rb2 (0.74 mg/ml) changes after 12 hours into compound Y (0.27 mg/ml) and CK (0.1 mg/ml). | [54] |

| β-glu@Cu(PTA) biocomposite | Rb1→Rd→F2→CK | PH=3, Temp=45°C, Time=24h | In these conditions, the conversion of the rare ginsenoside CK achieved 49.15%. | [55] |

| β-Glu&SN@Zn-BTC (β-Glu and snailase were co-immobilized on Zn-BTC) biocomposite | Rb1→Rd→F2→CK | PH =4.5 Temp =50°C Time =48h |

The CK conversion rate achieved 53.5%. | [56] |

| Sna&β-Glu@H-Cu-BDC biocomposite | Rb1→Rd→F2→CK | PH =4.5 Temp =50°C Time =48h |

The average conversion efficiency was about 60.12%, and the concentration of CK was roughly 0.94 mg mL−1. | [57] |

| Disease | Experimental models | Dosage form | Doses of administrations |

Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | C57BL/6J mice | Oral | 15, 30, 60 mg/kg |

|

[13] |

| Male C57BL/6J and ob/ob (B6/JGpt-Lepem1Cd25/Gpt) mice | i.p. injection | 20 mg/kg |

|

[77] | |

| 3T3-L1 cell lines | Cell treatment | 0.05, 0.5, 5 µM |

|

[19] | |

| 3T3-L1 cell lines | Cell treatment | 20, 50 µM |

|

[78] | |

| 3T3-L1 cell lines | Cell treatment | 10-40 µM |

|

[79] | |

| Diabetes | male ICR mice | Oral | 30 mg/kg/day |

|

[80] |

| Male Wistar rats (200–250 g) | oral | 30, 100, 300 mg/kg BW |

|

[81] | |

| MIN6 cell line | Cell treatment | 2-32 μM |

|

[37] | |

| male C57BL/KsJ db/db mice | oral | CK: Metformin 1:15 |

|

[82] | |

| DN | HFD (high-fat diet)/STZ (streptozotocin)-induced DN mice model | intragastrically | 10, 20, 40 mg/kg/day |

|

[83] |

| DT | human tenocytes cell | Cell treatment | 3, 10 µM |

|

[84] |

| OP |

Raw264.7 cells Balb/C female mice |

Cell treatment, i.p. injection |

10 µM 10 mg/kg |

|

[85] |

|

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats |

Cell treatment, i.p. injection |

2.5-40 µM 10 µM |

|

[86] | |

| OA | MC3T3E1 cell lines | Cell treatment | 0.01-10 µM |

|

[31] |

| NAFLD |

SD rats, HSC-T6 cells |

i.p. injection Cell treatment |

3mg/kg/day |

|

[87] |

| HepG2 cells | Cell treatment | 20 µM |

|

[33] | |

| HuH7 cells | Cell treatment | 1 µM |

|

[88] | |

| HCC | HepG2 cells | Cell treatment | 0, 5 and 10 µmol |

|

[89] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).