Submitted:

04 February 2024

Posted:

05 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Donkey Facilities

2.3. Survey method

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Facilities, Personnel and Donkeys involved in AAI

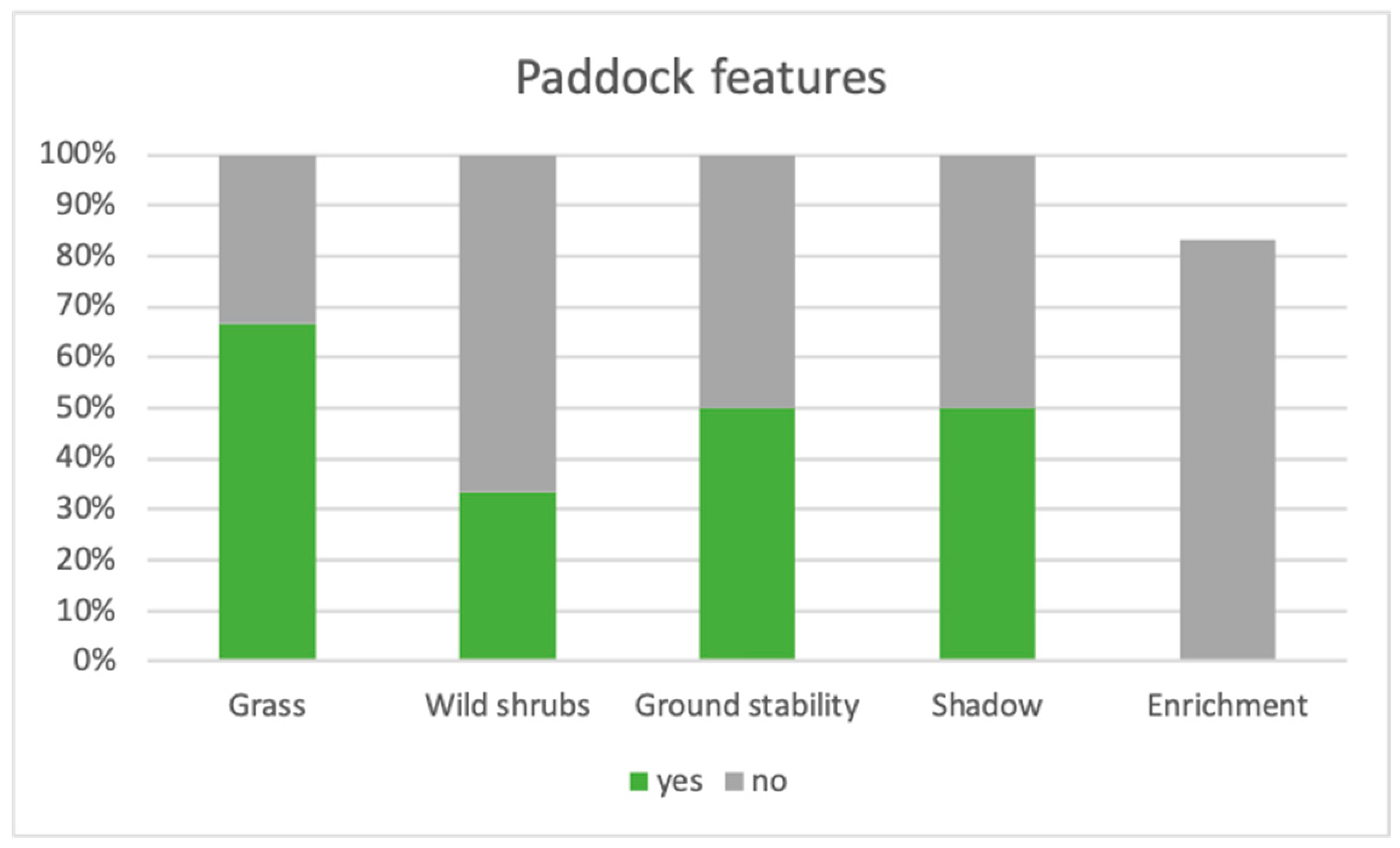

3.2. Housing

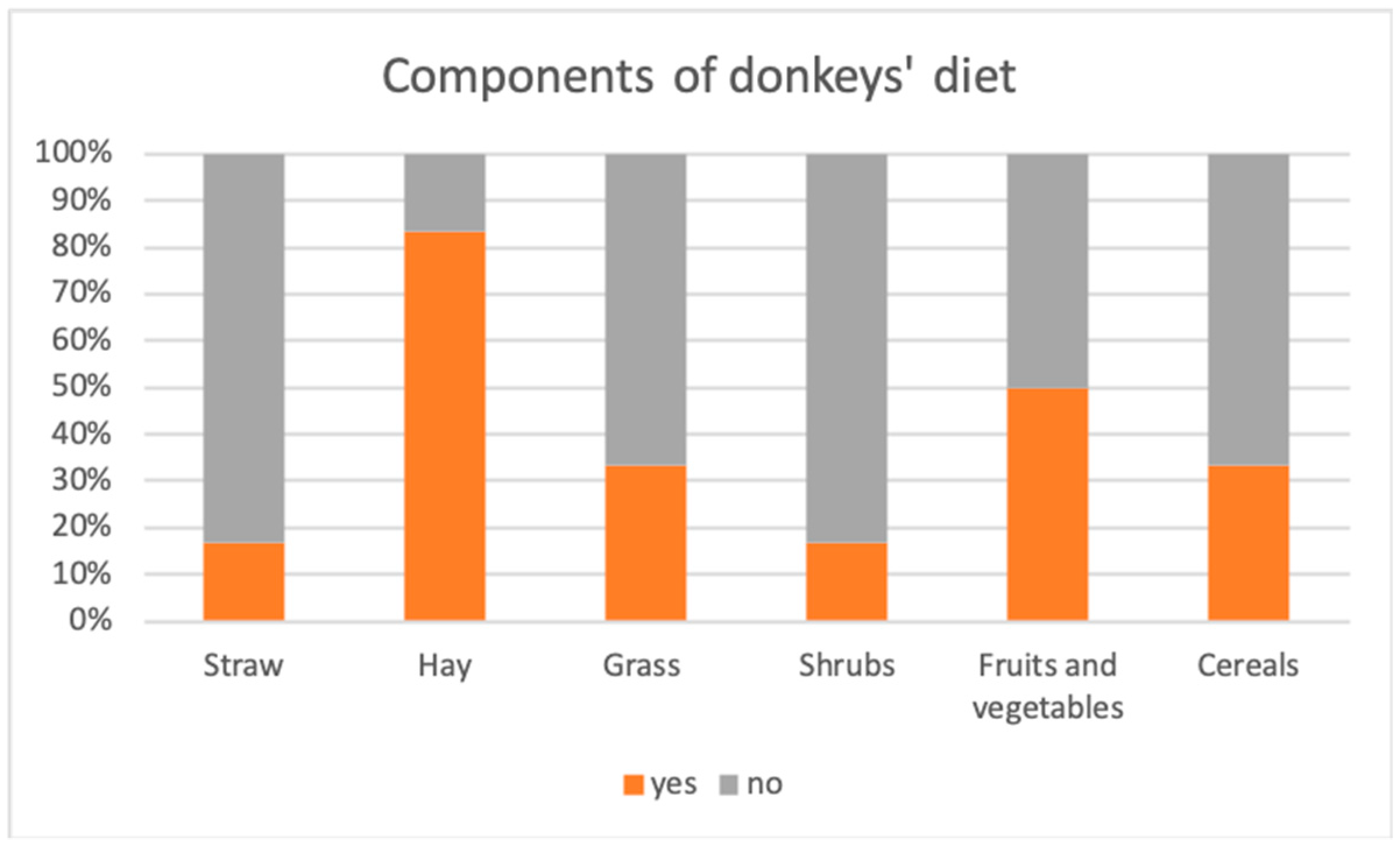

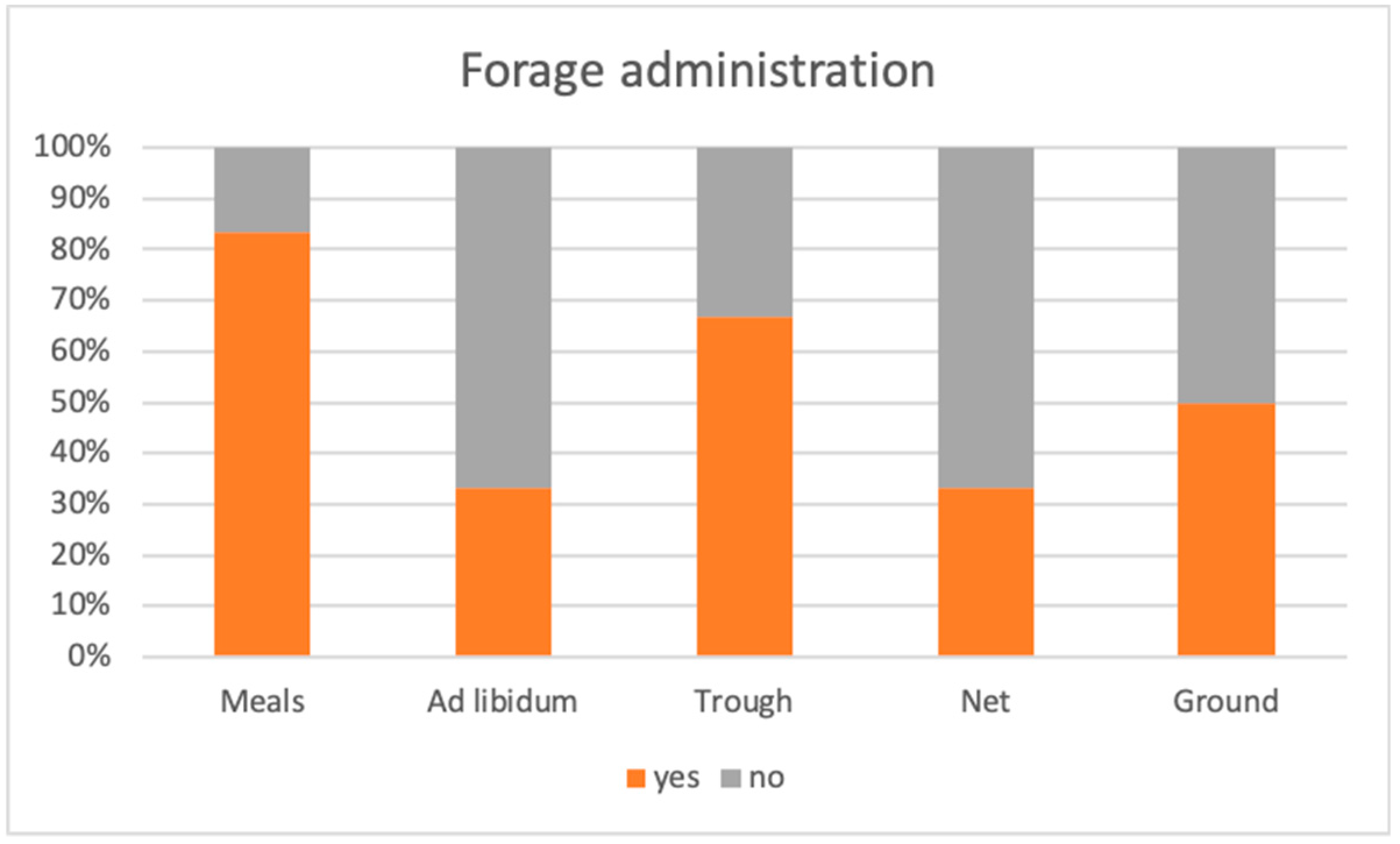

3.3. Feeding

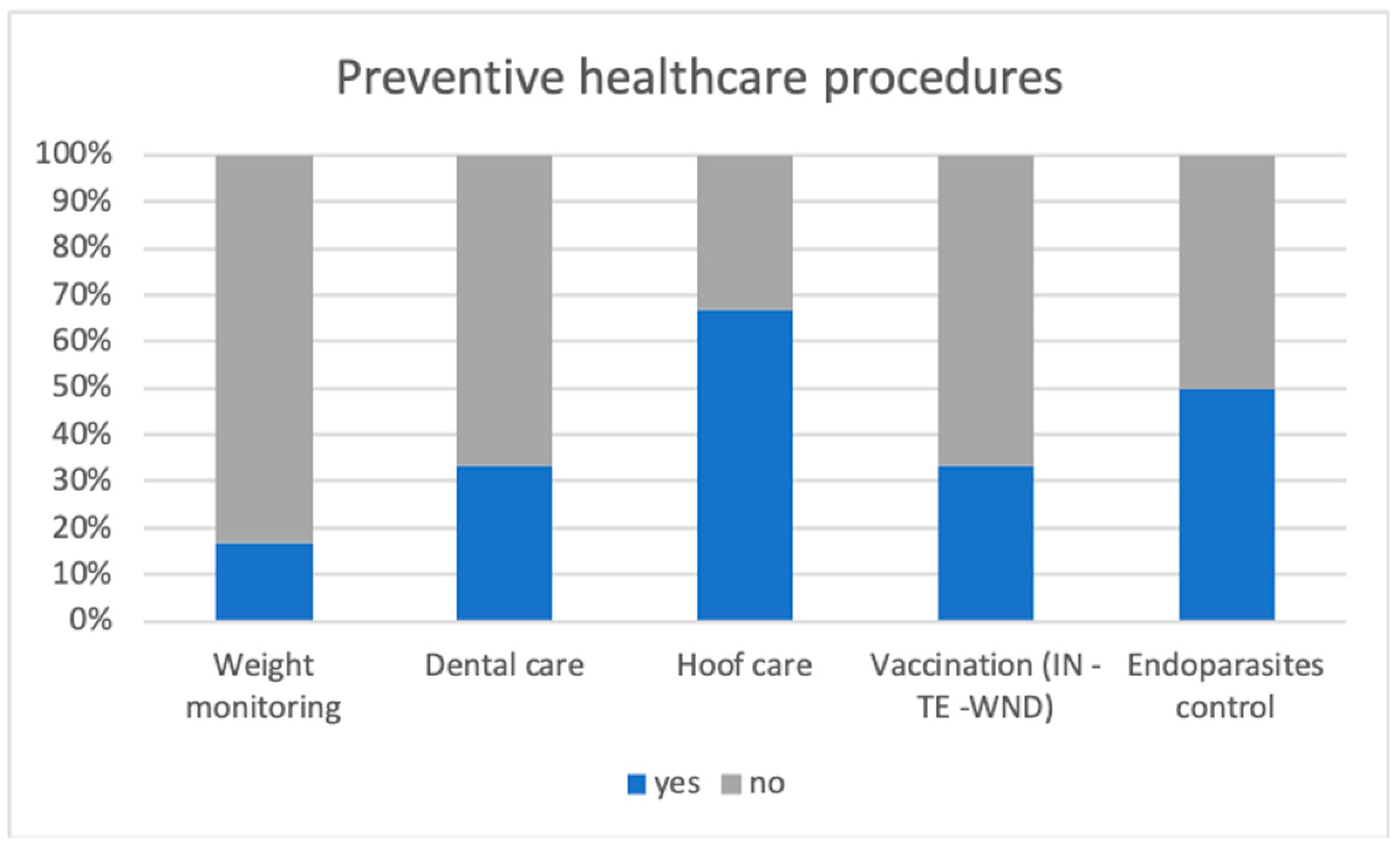

3.5. Preventive healthcare procedures

4. Discussion

4.1. Housing: from Mere Containment to Dynamic Context

4.2. Feeding: Managing Nutrition from both a Nutritional and Behavioral Perspective

4.3. Preventive Healthcare Procedures: Let Us Make Prevention a Keyword

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, E. Donkey and Mule Welfare. Veterinary Clinics of North America. Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Baber, M.; Hussain, T.; Awan, F.; Nadeem, A. The Contribution of Donkeys to Human Health. Equine Vet. J. 2014, 46, 766–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Effects of Donkey Milk on Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Tricò, D.; Lapenta, R.; Salari, F. Current Knowledge on Functionality and Potential Therapeutic Uses of Donkey Milk. Animals 2021, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, M.; Contalbrigo, L.; Simonato, M.; Ruzza, M.; Toson, M.; Farina, L. Animal Assisted Interventions in Practice: Mapping Italian Providers. Vet. Ital. 2018, 54, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galardi, M.; Filugelli, L.; Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Mutinelli, F.; Diaz, S.E.; Contalbrigo, L. Challenges and Perspectives of Social Farming in North-Eastern Italy: The Farmers’ View. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borioni, N.; Marinaro, P.; Celestini, S.; Del Sole, F.; Magro, R.; Zoppi, D.; Mattei, F.; Armi, V.D.; Mazzarella, F.; Cesario, A.; et al. Effect of Equestrian Therapy and Onotherapy in Physical and Psycho-Social Performances of Adults with Intellectual Disability: A Preliminary Study of Evaluation Tools Based on the ICF Classification. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicé, F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Menna, L.F.; Freda, M.F. Rencontrer l’émotion! Application Du Modèle Frédéricain Pour Le Zoothérapie à Une Expérience de l’éducation Assistée Par Animal (EAA) Dans Une École Primaire. Prat. Psychol. 2017, 23, 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-De Cara, C.A.; Perez-Ecija, A.; Aguilera-Aguilera, R.; Rodero-Serrano, E.; Mendoza, F.J. Temperament Test for Donkeys to Be Used in Assisted Therapy. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 186, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaro, S.; Maresca, G.; Raffa, A.; Gemelli, G.; Aliberti, B.; Calabrò, R.S. Donkey Therapy and Hippotherapy: Two Faces of the Same Coin? Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lima, Y.F.; Tatemoto, P.; Santurtun, E.; Reeves, E.; Raw, Z. The Human-Animal Relationship and Its Influence in Our Culture: The Case of Donkeys. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2021, 58, e174255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute Italiano. Linee Guida Nazionali per gli Interventi Assistiti con gli Animali (IAA), 2015.

- Wijnen, B.; Martens, P. Animals in Animal-Assisted Services: Are They Volunteers or Professionals? Animals 2022, 12, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J.P.; Kiess, A.S.; Mench, J.A.; Newberry, R.C.; Hester, P.Y. The Effect of Cage and House Design on Egg Production and Egg Weight of White Leghorn Hens: An Epidemiological Study. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 1522–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowel, V.; Rennie, L.; Tierney, G.; Lawrence, A.; Haskell, M. Relationships between Building Design, Management System and Dairy Cow Welfare. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trocino, A.; Xiccato, G. Animal Welfare in Reared Rabbits: A Review with Emphasis on Housing Systems. World Rabbit. Sci. J. World Rabbit. Sci. Assoc. 2006, 14, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H. Key Determinants of Pig Welfare: Implications of Animal Management and Housing Design on Livestock Welfare. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Segati, G.; Brscic, M.; Chincarini, M.; Costa, E.D.; Ferrari, L.; Burden, F.; Judge, A.; Minero, M. Effects of Management Practices on the Welfare of Dairy Donkeys and Risk Factors Associated with Signs of Hoof Neglect. J. Dairy. Res. 2018, 85, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, A.H.; Griffin, T.C. Protecting Animal Welfare in Animal-Assisted Intervention: Our Ethical Obligation. Semin. Speech Lang. 2022, 43, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Pinillos, R. One Welfare Impacts of COVID-19—A Summary of Key Highlights within the One Welfare Framework. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarazona, A.M.; Ceballos, M.C.; Broom, D.M. Human Relationships with Domestic and Other Animals: One Health, One Welfare, One Biology. Animals 2020, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, A.K.; Navas González, F.J.; Canisso, I.F. Donkey and Mule Behavior. Vet. Clin. North. Am.-Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiemann, A. Clinical Approach to the Dull Donkey. Practice 2013, 35, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, E.; Rickards, K.J.; Thiemann, A.K. Clinical Evaluation and Preventative Care in Donkeys. Vet. Clin. North. Am.-Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Donkey Sanctuary. In The Clinical Companion of the Donkey 2018; ISBN 9781399908931.

- Galardi, M.; Contalbrigo, L.; Toson, M.; Bortolotti, L.; Lorenzetto, M.; Riccioli, F.; Moruzzo, R. Donkey Assisted Interventions: A Pilot Survey on Service Providers in North-Eastern Italy. Explore 2022, 18, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wensley, S.P. Animal Welfare and the Human-Animal Bond: Considerations for Veterinary Faculty, Students, and Practitioners. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2008, 35, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddy, E.; Burden, F.; Raw, Z.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Zappi Bello, J.H.; Brown, J.; Kaminski, J.; Proops, L. Belief in Animal Sentience and Affective Owner Attitudes Are Linked to Positive Working Equid Welfare across Six Countries. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Costa, E.; Dai, F.; Murray, L.A.M.; Guazzetti, S.; Canali, E.; Minero, M. A Study on Validity and Reliability of On-Farm Tests to Measure Human-Animal Relationship in Horses and Donkeys. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 163, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M.; Johnson, K.G. One Welfare, One Health, One Stress: Humans and Other Animals. In Stress and Animal Welfare. Key Issues in the Biology of Humans and Other Animals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 19, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Waiblinger, S. Animal Welfare and Housing. In Welfare of Production Animals: Assessment and Management of Risks; Smulders, F., Algers, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 5, pp. 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Sicilia, A. della S.D. per le A.S. e O.E. Procedure di valutazione per il rilascio del nulla osta ai centri specializzati in TAA/EAA e alle strutture non specializzate che erogano TAA/EAA; 2018.

- Couto, M.; Santos, A.S.; Laborda, J.; Nóvoa, M.; Ferreira, L.M.; Madeira de Carvalho, L.M. Grazing Behaviour of Miranda Donkeys in a Natural Mountain Pasture and Parasitic Level Changes. Livest. Sci. 2016, 186, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Burden, F.; Gosden, L.; Proudman, C.; Trawford, A.; Pinchbeck, G. Case Control Study to Investigate Risk Factors for Impaction Colic in Donkeys in the UK. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 92, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, T.; King, M.; Perkins, E.; McGowan, C.; Chubbock, S.; Hannelly, E.; Rogers, J.; Pinchbeck, G. An Exploration of Environmentally Sustainable Practices Associated with Alternative Grazing Management System Use for Horses, Ponies, Donkeys and Mules in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.; Thiemann, A. Donkeys Are Different. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddy, E.; Burden, F.; Proops, L. Shelter Seeking Behaviour of Healthy Donkeys and Mules in a Hot Climate. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 222, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruet, A.; Lemarchand, J.; Parias, C.; Mach, N.; Moisan, M.P.; Foury, A.; Briant, C.; Lansade, L. Housing Horses in Individual Boxes Is a Challenge with Regard to Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochais, C.; Henry, S.; Fureix, C.; Hausberger, M. Investigating Attentional Processes in Depressive-like Domestic Horses (Equus Caballus). Behav. Process. 2016, 124, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fureix, C.; Beaulieu, C.; Argaud, S.; Rochais, C.; Quinton, M.; Henry, S.; Hausberger, M.; Mason, G. Investigating Anhedonia in a Non-Conventional Species: Do Some Riding Horses Equus Caballus Display Symptoms of Depression? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 162, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Meierhöfer, S.; Klaer, S.; Ammon, C.; Brunsch, R.; Hoffmann, G. Activity Behavior of Horses Housed in Different Open Barn Systems. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2010, 30, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Büttner, K.; Salau, J.; Krieter, J.; Czycholl, I. Area and Resource Utilization of Group-Housed Horses in an Active Stable. Animals 2021, 11, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, F. Practical Feeding and Condition Scoring for Donkeys and Mules. Equine Vet. Educ. 2012, 24, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.A.; Bell, N. Donkey Nutrition and Malnutrition. Vet. Clin. North. Am.-Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, J.B.; Goodwin, D.; Kennedy, M.J.; Davidson, H.P.B.; Harris, P. Foraging Enrichment for Individually Housed Horses: Practicality and Effects on Behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoot, I.; Callebaut, J.; Demeulenaere, E.; Vandenberghe, C.; Hoffmann, M. Foraging Behaviour of Donkeys Grazing in a Coastal Dune Area in Temperate Climate Conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 92, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rosset, W. Donkey Nutrition and Feeding: Nutrient Requirements and Recommended Allowances—A Review and Prospect. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 65, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.A.; Du Toit, N.; Hazell-Smith, E.; Trawford, A.F. Hyperlipemia in a Population of Aged Donkeys: Description, Prevalence, and Potential Risk Factors. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seganfreddo, S.; Fornasiero, D.; De Santis, M.; Contalbrigo, L.; Mutinelli, F.; Normando, S. Investigation of Donkeys Learning Capabilities through an Operant Conditioning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 255, 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osthaus, B.; Proops, L.; Hocking, I.; Burden, F. Spatial Cognition and Perseveration by Horses, Donkeys and Mules in a Simple A-Not-B Detour Task. Anim. Cogn. 2013, 16, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, F.A.; Gallagher, J.; Thiemann, A.K.; Trawford, A.F. Necropsy Survey of Gastric Ulcers in a Population of Aged Donkeys: Prevalence, Lesion Description and Risk Factors. Animal 2009, 3, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, F.A.; Bell, N. Donkey Nutrition and Malnutrition. Vet. Clin. North. Am.-Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broom, D.M. Behaviour and Welfare in Relation to Pathology. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 97, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickards, K.; Toribio, R.E. Clinical Insights: Recent Advances in Donkey Medicine and Welfare. Equine Vet. J. 2021, 53, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiemann, A.K.; Poore, L.A. Hoof Disorders and Farriery in the Donkey. Veterinary Clinics of North America. Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prontuario Ufficiale AISA. Elenco Prodotti Per la Cura Degli Animali. 2024. Available online: https://www.prontuarioveterinario.it/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Corbett, C.J.; Love, S.; Moore, A.; Burden, F.A.; Matthews, J.B.; Denwood, M.J. The Effectiveness of Faecal Removal Methods of Pasture Management to Control the Cyathostomin Burden of Donkeys. Parasite Vectors 2014, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Procedure | Description |

| Weigh monitoring | Weight measurement or estimation through chest circumferenceand height at the withers |

| Dental care | Dental check-up and corrective interventions |

| Hoof care | Hoof check and potential trimming |

| Vaccinations | Vaccinations for Equine Influenza, Tetanus and West Nile Disease |

| Fecal exam | Fecal exam and selective treatment (vs blindly administration of anthelmintic drug) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).