Preprint

Article

DFT Studies of Dimethylaminophenyl-substituted Phthalocyanine and of Its Silver Complexes

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

05 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

Abstract

The dimethylaminophenyl-substituted silver phthalocyanine [dmaphPcAg] can be used as a UV-vis photoinitiator for in situ preparation of a silver/polymer nanocomposite. To verify early steps of the supposed mechanism of radical polymerization, we performed quantum chemical calculations of m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes with charges q = +1 to -2 in the two lowest spin states m, of a free ligand and its dehydrogenated/deprotonated products m[dmaphPcHn]q, n = 2 to 0, q= 0, -1 or -2, in the lowest spin states m. The calculated electronic structures and electron transitions of all the optimized structures in CHCl3 solutions are compared with experimental EPR and UV-vis spectra, respectively. The unstable 3[dmaphPcAg]+ species deduced only from previous EPR spin trap experiments was identified. In addition to 2[dmaphPcAg]0, our results suggest the coexistence of both reaction intermediates 1[dmaphPcAg]- and 3[dmaphPcAg]- in reaction solutions. Silver nanoparticle formation is a weak point of the supposed reaction mechanism from the energetic, stereochemistry, and electronic structure points of view.

Keywords:

B3LYP hybrid functional

; solvent effect

; geometry optimization

; electron structure

; spin density

; electron transitions

supplementary.pdf (532.54KB )

1. Introduction

Phthalocyanine (C8H4N2)4H2 (PcH2) contains four isoindole units connected by nitrogen bridges. The so-obtained ring system has 18 delocalized π electrons responsible for intense absorption (the Soret band around 400 nm and the Q-band in the red/near infrared region). Therefore, phthalocyanines are used as dyes and pigments 1. Metal complexes derived from Pc2- have applications in catalysis, solar cells, and photodynamic therapy [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

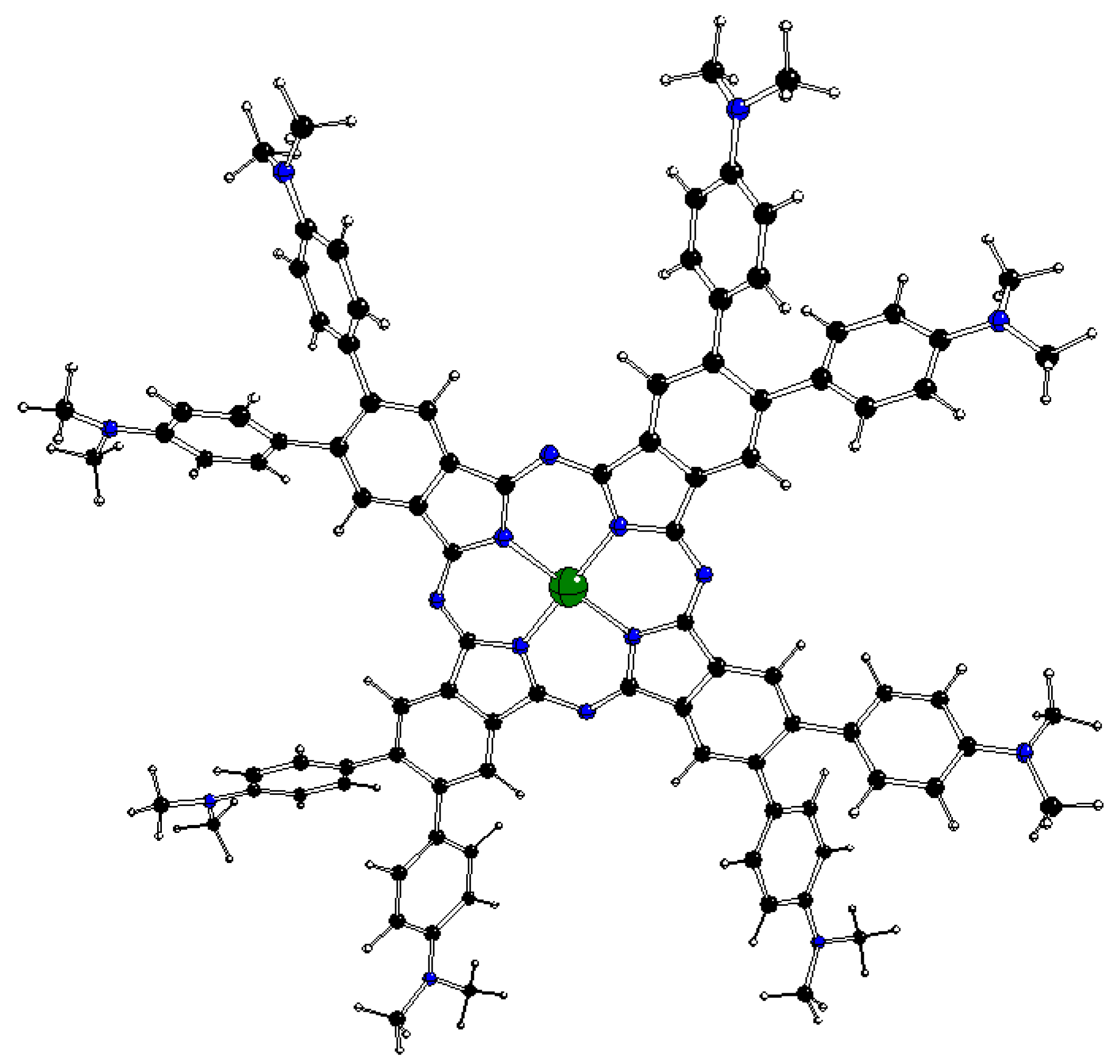

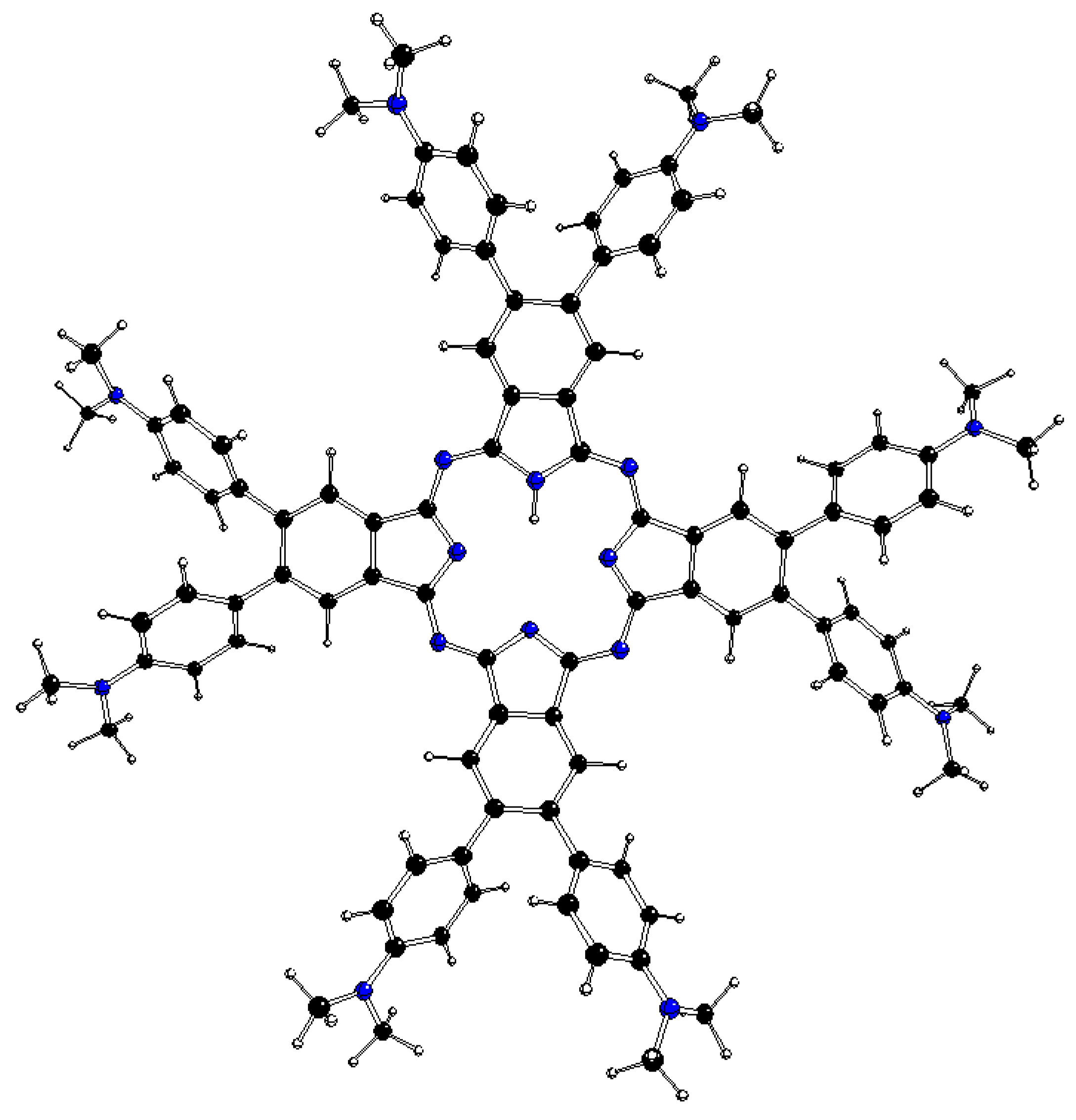

Very high absorption in the visible range and high chemical resistance implied the synthesis of complexes of various substituted phthalocyanines with central Al, Mg, and Zn atoms [18,19,20,21,22] to be used as photoinitiators for free-radical (FRP) and/or cationic (CP) polymerizations. Recently, Breloy et al. [23] have synthesized a complex of dimethylaminophenyl-substituted phthalocyaninewith silver in an unusual oxidation state +II, [dmaphPcAg] (see Figure 1). The species obtained by photoinduced electron transfer reactions of excited [dmaphPcAg]* in the presence and absence of bis(4-methylphenyl)iodonium hexafluorophosphate (Iod) initiated CP and FRP, respectively, both in laminate; as well as under air. Moreover, a polymer/silver nanocomposite with a homogenous narrow size distribution of spherical silver nanoparticles has been formed.

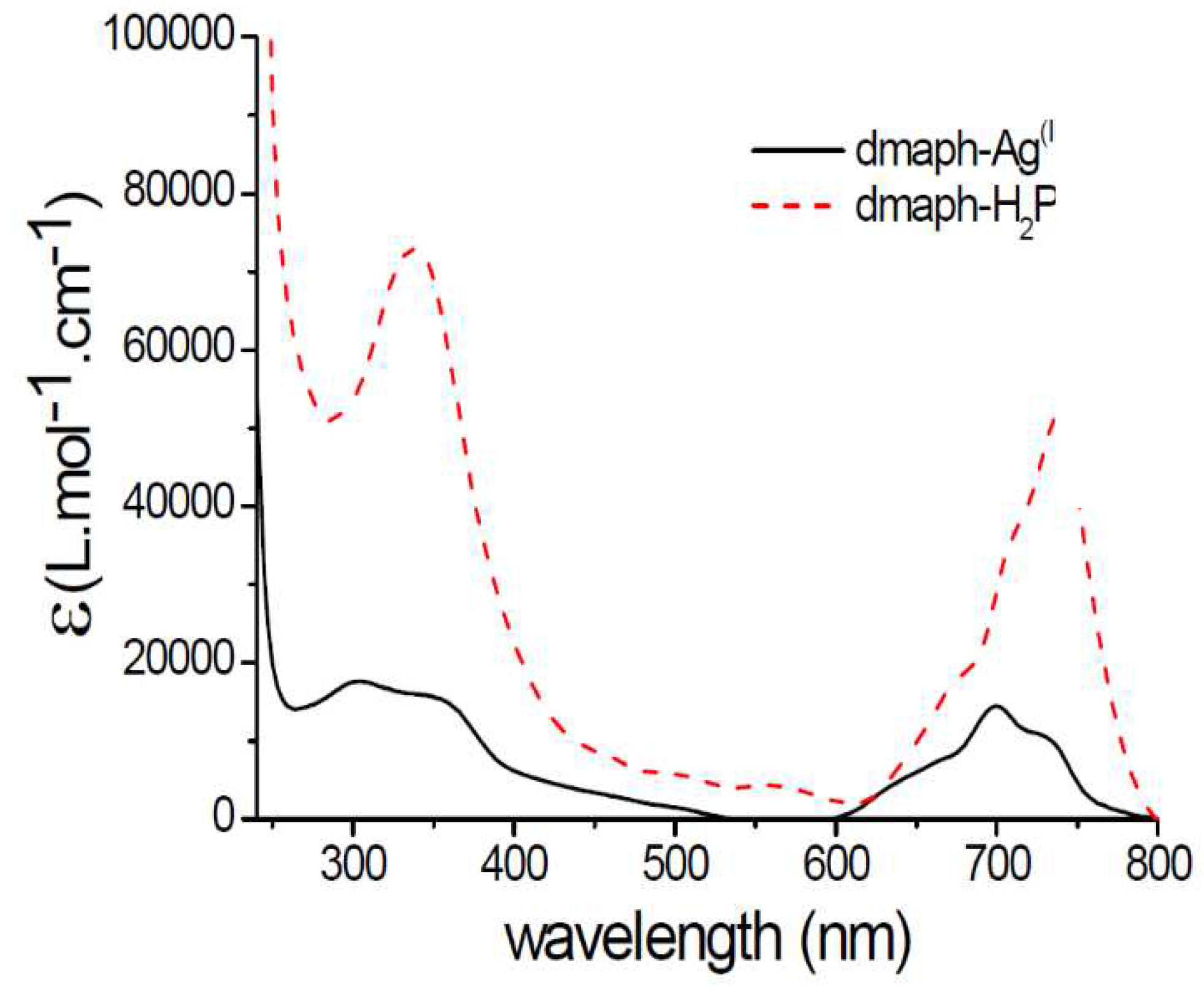

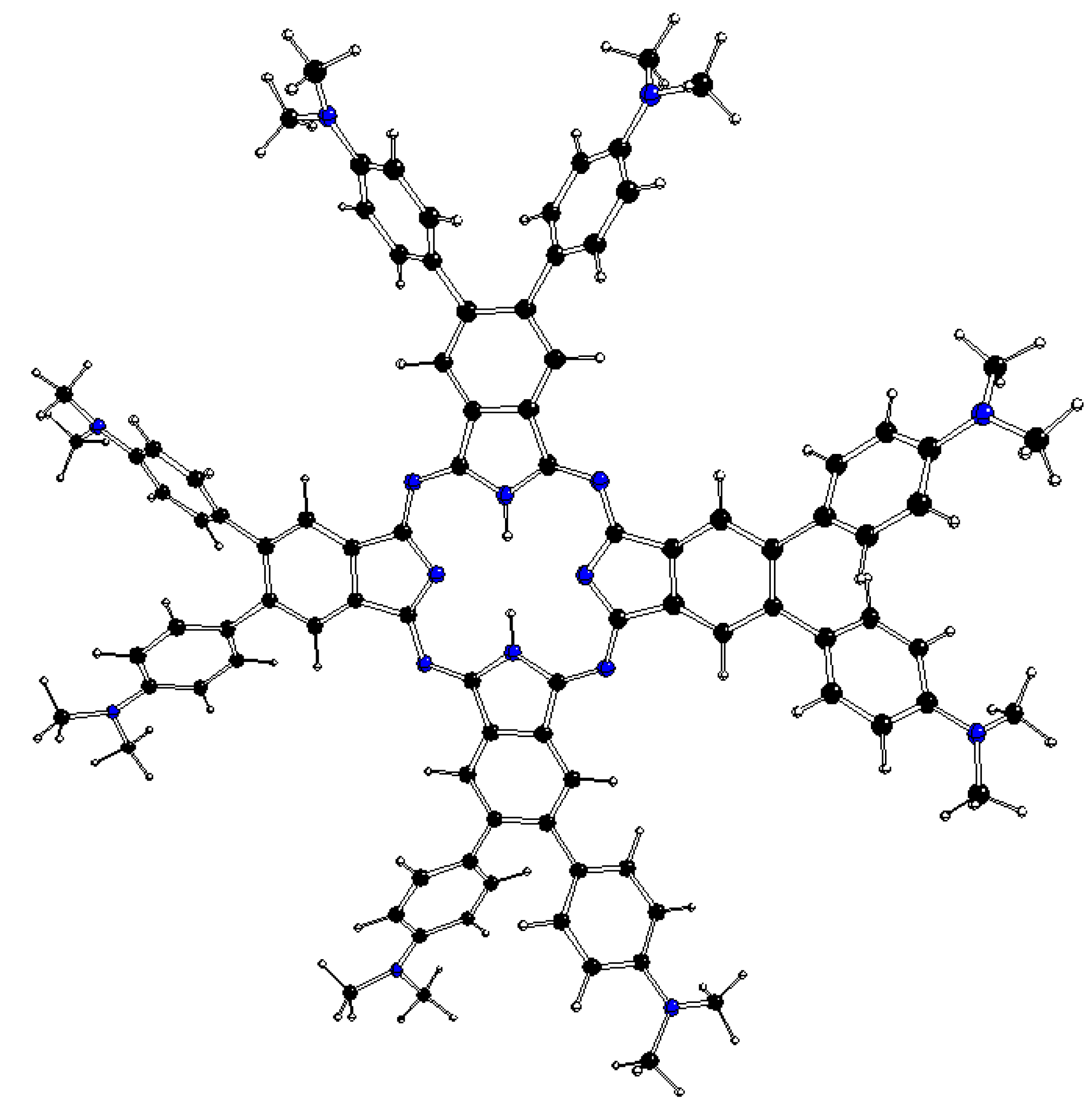

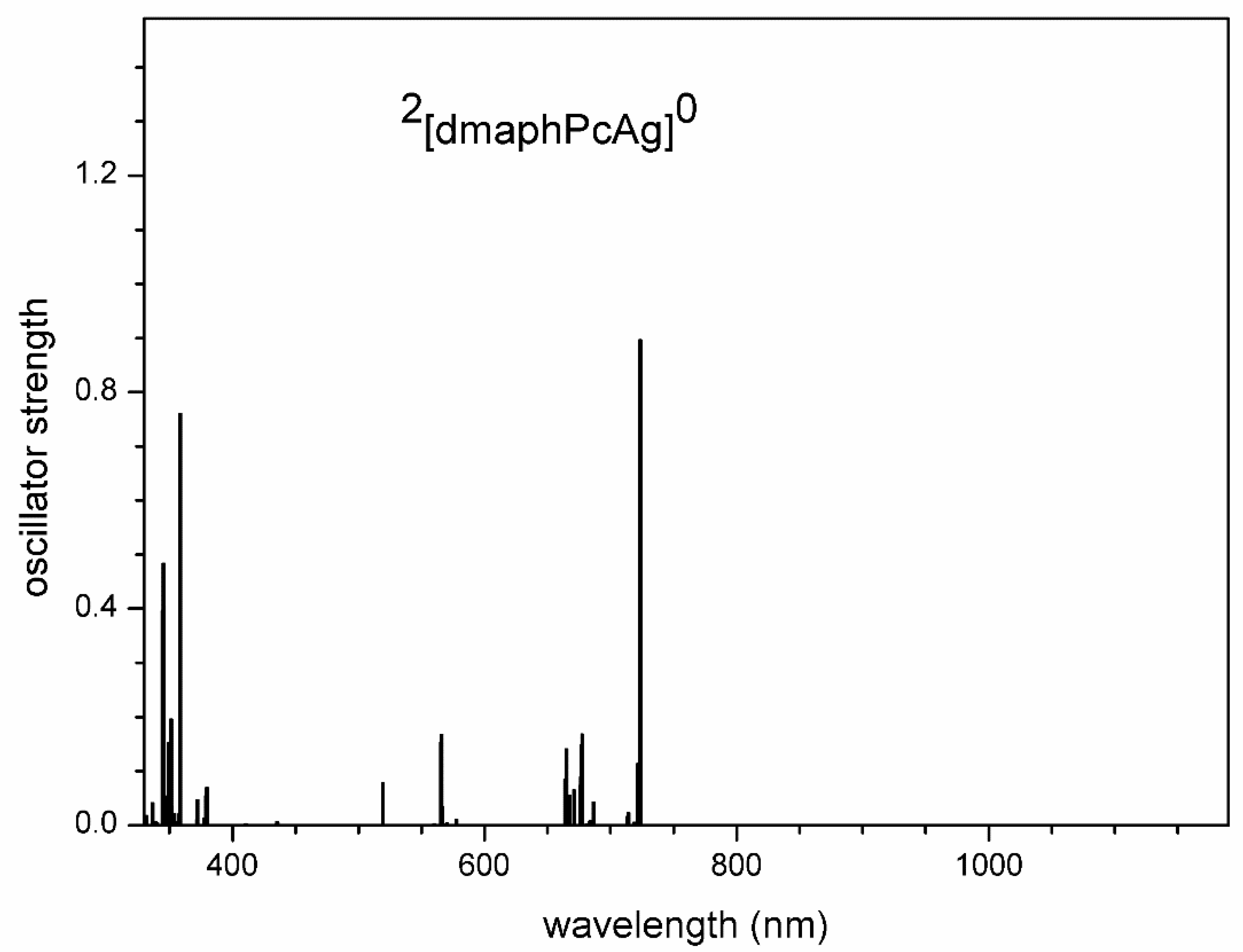

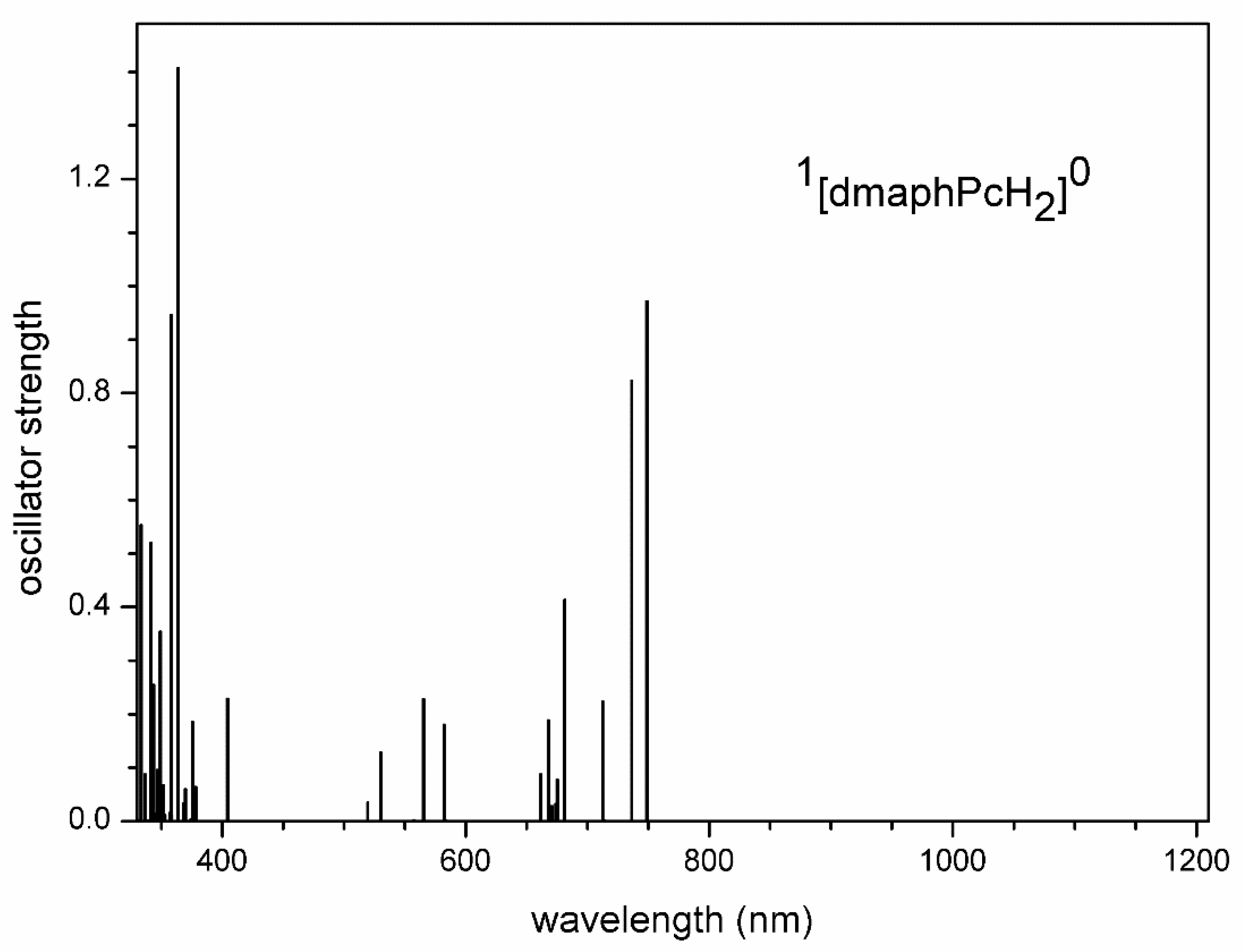

Our recent study will deal with the results related to [dmaphPcAg] and its reaction intermediates in more detail [23]. Its UV-vis absorption spectrum in CHCl3 shows two intense absorption peaks at ca. 300 - 360 nm (Soret band) and at 700 nm (Q-band) (see Figure 2). According to TD-B3LYP/SMD (see below) calculations of its neutral molecule in doublet ground spin state), 2[dmaphPcAg]0, the Soret band corresponds most probably to π – π* ligand-metal electron transitions at 359 nm (oscillator strength f = 0.76). The Q-band consists of π – π* electron transitions at 723 nm (f = 0.9) and at 724 nm (f = 0.79). Analogously, in the neutral dmaphPcH2 molecule in singlet ground state (Figure 3) the Soret band at ca 340 nm could be ascribed to π – π* electron transitions at 376 nm (f = 0.19) and at 404 nm (f = 0.23) and the Q-band at ca 740 nm is explained by π – π* electron transitions at 736 nm (f = 0.82) and at 713 nm (f = 0.22).

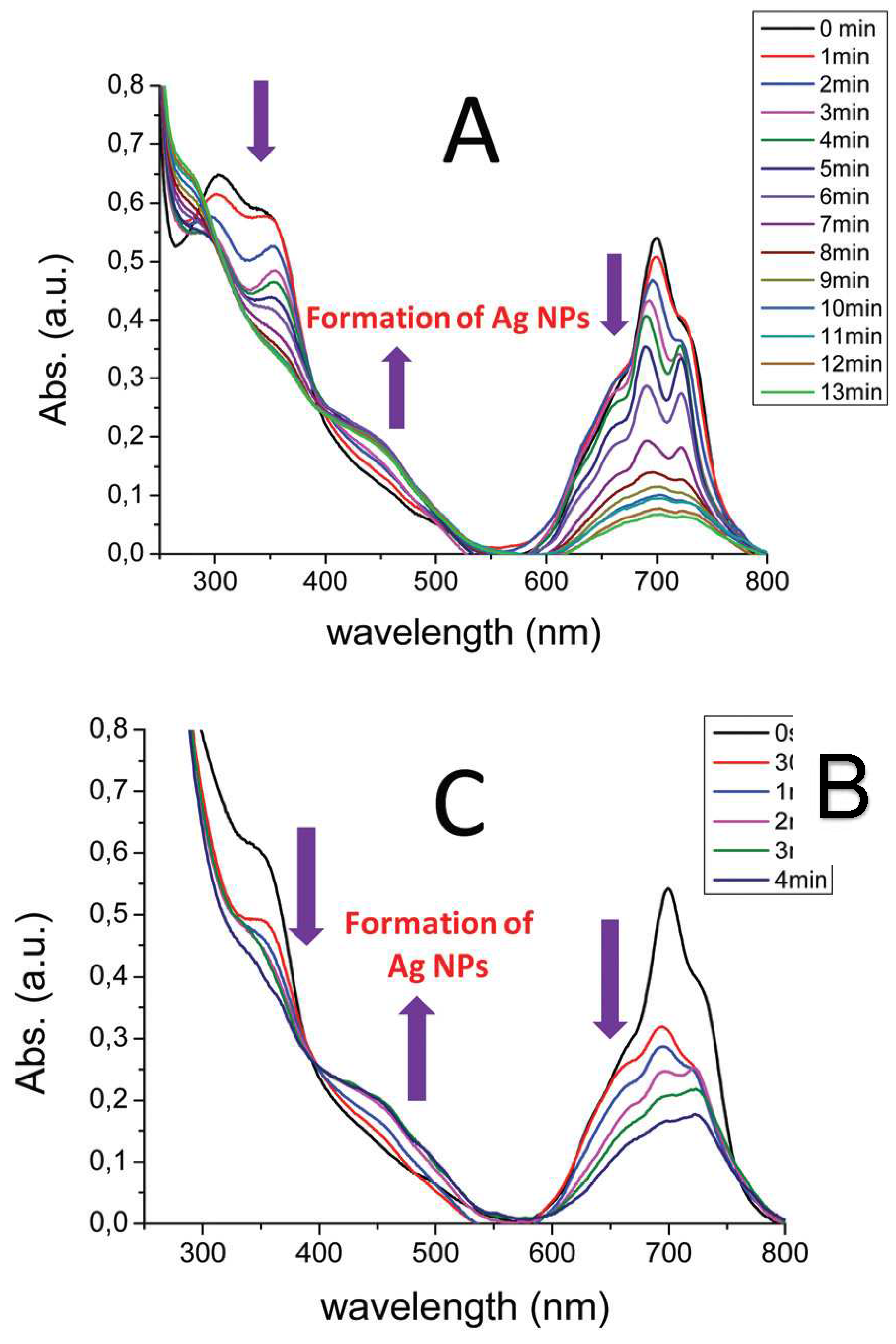

Under exposure to LED @ 385 nm of [dmaphPcAg] in CHCl3 solutions with and without Iod, a sharp decrease in absorbance at 359 and 723 nm is observed simultaneously with splitting the Q-band and a rapid increase in a band at 450 nm indicating the formation of silver nanoparticles (see Figure 4) [23]. Well-dispersed spherical Ag nanoparticles in the solution (an average diameter of 9 nm) were confirmed by transmission electron microscopy. Fluorescence quenching increases with Iod concentration in a chloroform solution, which suggests an electron transfer reaction from the [dmaphPcAg] excited state to Iod.

A very weak EPR signal of in situ irradiated [dmaphPcAg] in CHCl3 using LED@385 nm was detected at g = 2.0021 and its intensity was enhanced in the presence of Iod [23]. It can be assigned to an unstable π-radical cation which is probably transformed into a N-centered radical that was detected as an adduct with N-benzylidene-tert-butylamine N-oxide (PBN) or 2,2-dimethyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrrole 1-oxide (DMPO). The carbon- and nitrogen-centered radicals were detected in similar EPR experiments with PBN and DMPO spin-traps in deoxygenated benzene under argon as well.

LED@385 nm irradiation of [dmaphPcAg] in CHCl3 with Iod under argon formed a π-radical cation centered on [dmaphPcAg]. Stable (4-methyl)phenyl radical adducts with PBN, DMPO and nitrosodurene spin traps were detected in similar experiments in deoxygenated benzene under argon as well.

The Iod addition to [dmaphPcAg] photoinitiating systems caused higher conversions of epoxy and acrylate monomers [23]. Similar results can be obtained by cationic photopolymerization using the dmaphPcH2/Iod system and dmaphPcH2 alone. Therefore, the presence of Ag is not crucial for photopolymerization. Because radical species are strongly inhibited by oxygen, FRP does not proceed well in air. Unlike acrylate conversions, epoxy conversions are not affected by atmosphere conditions. Another interesting attribute of the above [dmaphPcAg] photoinitiating systems is the electron transfer reactions where the central Ag(II) atom is reduced to homogenously dispersed silver nanoparticles in the polymer matrix.

The following [dmaphPcAg] photoinitiation mechanism was proposed [23]:

The photoexcited [dmaphPcAg]* is formed by irradiation in the first step

[dmaphPcAg] + hυ → [dmaphPcAg]*

The reaction between photoexcited and ground-state species leads to the reduction of

Ag(II) to Ag(I) and generates the nitrogen-centered cation-radical in the second step

[dmaphPcAg]* + [dmaphPcAg] → [dmaphPcAg]- + [dmaphPcAg]+•

In the third step, silver nanoparticles and aromatic carbon-centered radicals are formed.

[dmaphPcAg]- → Ag0 + [dmaphPc]-•

Subsequently, a hydrogen-transfer reaction between [dmaphPcAg]+• and [dmaphPcAg] leads to dehydrogenated aromatic-derived aminoalkyl radicals [dmaphPcAg - H]• and Brønsted photoacids H+ according to (4)

[dmaphPcAg]+• + [dmaphPcAg] → [dmaphPcAg] + [dmaphPcAg - H]• + H+

The Brønsted acids subsequently initiate ring-opening reactions in epoxides. [dmaphPc]-• and [dmaphPcAg - H]• initiate the FRP of acrylates.

The addition to [dmaphPcAg] is the source of additional CP reactions. Upon irradiation, the exciplex [dmaphPcAg…(MePh)2I+]* is formed

[dmaphPcAg] + (MePh)2I+ + hυ → [dmaphPcAg…(MePh)2I+]*

Subsequently, it undergoes electron transfer (6), where the [dmaphPcAg] +• cation-radical and a diaryliodo radical are formed

[dmaphPcAg…(MePh)2I+]* → [dmaphPcAg] +• + (MePh)2I•

Similar electron transfer reactions as above within [dmaphPcAg]* cause the formation of silver nanoparticles, [dmaphPc]-•, [dmaphPcAg-H]•, and photoacids - see Eqs. (2) – (4). The intermediate diaryliodo radical is unstable and decomposes as follows

(MePh)2I• → MePh• + MePhI

So formed phenyl radicals can abstract hydrogen and produce the derived aromatic aminoalkyl radical [dmaphPcAg-H] •

[dmaphPcAg] + MePh• → [dmaphPcAg-H] • + MePhH

The generated [dmaphPc]-• and [dmaphPcAg-H]• radicals are able to initiate the FRP of acrylates.

Nevertheless, the above reaction mechanism (1) – (8) meets several problems. Whereas [dmaphPcAg], [dmaphPcAg]* and [dmaphPcAg…(MePh)2I+]* have an odd number of electrons and their doublet ground spin state corresponds to natural radicals, [dmaphPcAg]-, [dmaphPcAg]+, and the monodehydrogenated species [dmaphPcAg - H] have an even number of electrons and so they can form biradicals. These correspond to singlet or triplet spin states, but the singlet biradicals are not detectable by EPR measurements. Consequently, quantum-chemical calculations are necessary to describe their spin densities. In [23] quantum-chemical calculations of neutral [dmaphPcAg] in doublet spin state and neutral [dmaphPcH2] in singlet spin state were performed only. In our more recent (TD-)B3LYP study [24] optimal geometries, electronic structure and electron transitions of m[dmaphPcAg]q species in vacuum with charges q = +1 to -2 in the two lowest spin states m were investigated from the point of view of the Jahn-Teller effect. However, this study was not related to spin distribution in the m[dmaphPcAg]q species.

The aim of our recent manuscript is to complete the previous studies by DFT calculations of m[dmaphPcAg]q species in CHCl3 with various charges q corresponding to silver oxidation states between +III and 0 and in two lowest spin states m. We want to describe their electron- and spin-density distributions. To complete the picture, we will also study the dehydrogenated/deprotonated 1[dmaphPcH2]0 species in the lowest spin states. We hope that the obtained results on electronic structure, energetics and electron transitions will contribute to verification of the above mentioned reaction mechanism (1) – (3) [23].

2. Results

Geometry optimization of m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes in CHCl3 in two lowest spin states without any symmetry restriction (see below) started from their optimized structures in vacuum obtained in [24]. After suitable modifications, these structures were used as starting ones for analogous geometry optimizations of dehydrogenated/deprotonated species [dmaphPcH2] in the lowest two spin states as well. Although the singlet spin states of the systems under study were treated using an unrestricted formalism (the ‘broken symmetry’ treatment [25]), no spin-polarized solutions were obtained, i.e., their energies are identical as in the case of restricted DFT calculations. Gibbs free energies and relevant geometry parameters of the stable structures are presented in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

2.1. Energetics

According to the Gibbs free energy data at room temperature (Table 1), the energies of the m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes decrease upon reduction. However, even the structures of the [dmaphPcAg]2- complexes corresponding to the formal oxidation state Ag(0) seem to be stable. Except [dmaphPcAg]+, the complexes in lower spin states are more stable. It implies that the 3[dmaphPcAg]+ biradical can be present in non-vanishing concentrations in the reaction system. Consequently, reactions (2) and (6) are correct. Despite the relative concentrations of the deexcitation products of the excited [dmaphPcAg]* and [dmaphPcAg…(MePh)2I+]* species not necessarily satisfy the Boltzmann distribution law, our results indicate that only 1[dmaphPcAg]- and 3[dmaphPcAg]- species can co-exist in comparable concentrations. In equilibria, the remaining m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes with the same charges are present only in the more stable form because of the too large energy difference between their spin states. Therefore, if the LED@385 nm irradiation (corresponding to 310.7 kJ/mol energy) is fully absorbed by 2[dmaphPcAg]0 excitation, the reaction (2) is shifted to the right in agreement with [23] (the reaction Gibbs energy of -26.5 kJ/mol at 298 K).

According to the data in Table 1, deprotonated [dmaphPcHn]q species, n = 2 or 1, seem to be more stable than their dehydrogenated counterparts (i.e., with q preserved). However, their relative stability is also dependent on the reactions of their formation. The reaction Gibbs energy of 2Ag0 formation (with atomic Gibbs energy of -146.98864 Hartree) according to reaction (3) is highly positive (+235.0 kJ/mol for 3[dmaphPcAg]- and +240.7 kJ/mol for 1[dmaphPcAg]-) and its equilibrium is shifted right due to subsequent formation and precipitation of Ag nanoparticles. Due to the lack of necessary data, we will not deal with the remaining (4) – (8) reaction equilibria.

2.2. Geometries

The DFT optimized geometries of the m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes are very similar to the 2[dmaphPcAg]0 structure presented in Figure 1. Except for dimethylphenyl groups, all m[dmaphPcAg]q structures are planar, only the central Ag atom might be slightly above the plane of four pyridine nitrogen atoms Npy (up to 0.019 Å in 3[dmaphPcAg]+, see Table 2). The values of the lengths of the Ag – Npy bonds, as well as of the Npy – Ag – Npy angles indicate that the C4 symmetry axis is preserved in all the silver complexes except 4[dmaphPcAg]0, 1[dmaphPcAg]-, and 3[dmaphPcAg]-. The Ag – Npy bond lengths increase with complex reduction up to 1[dmaphPcAg]- only. Therefore, the electron density transfer to Ag is not related to its out-of-plane movement.

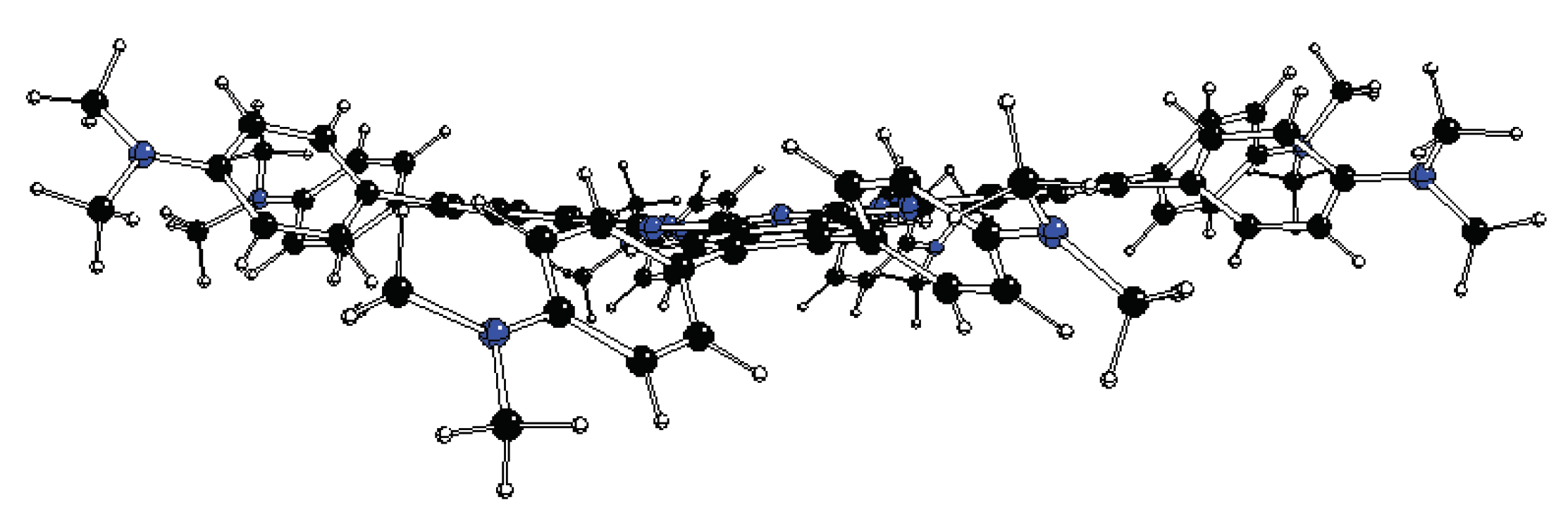

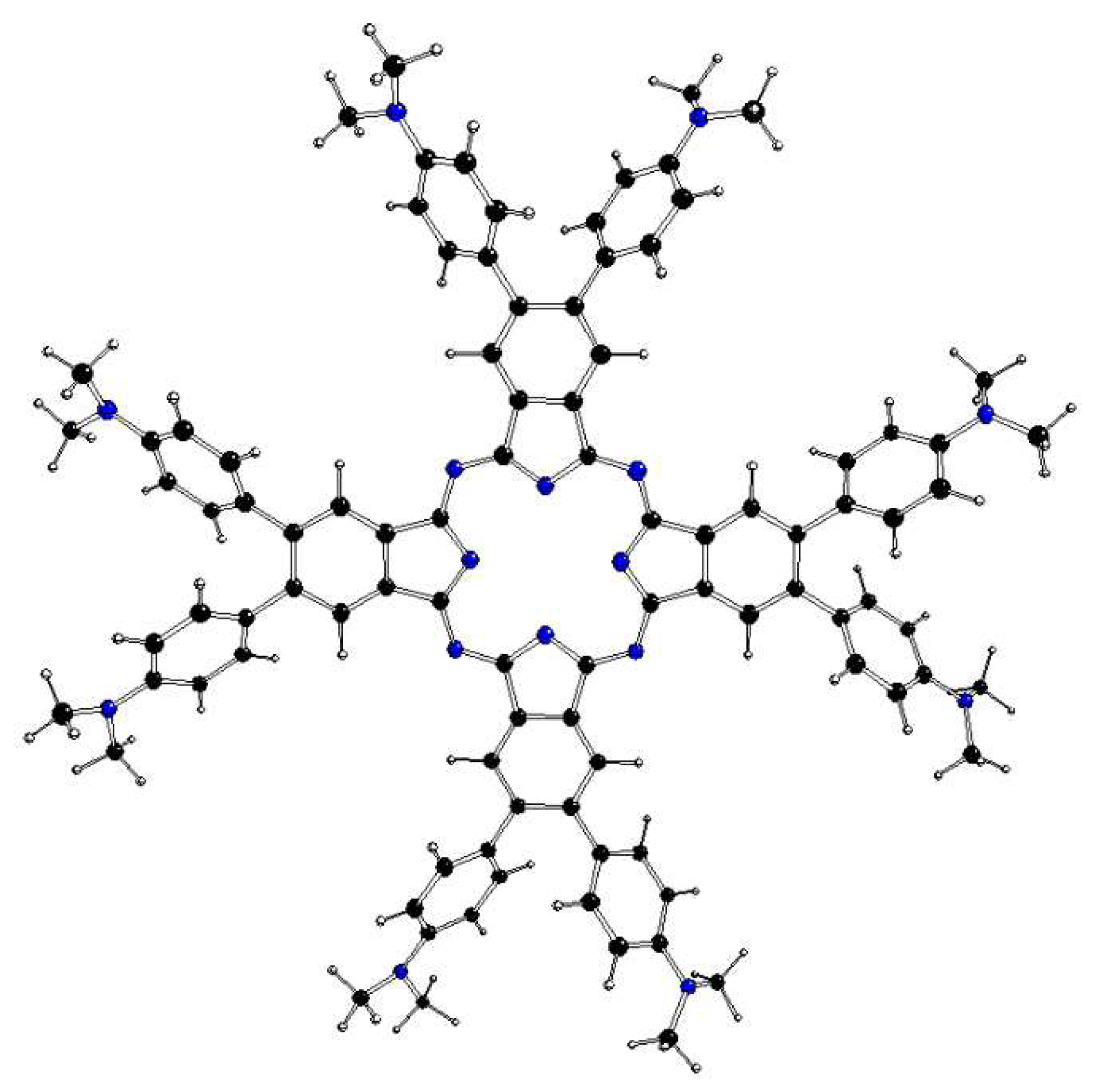

The DFT optimized structures of m[dmaphPcHn]q, n = 2 → 0, are presented in Figure 3, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figures S1 and S2 and in Table 3. Except for 1[dmaphPcH]-, their phthalocyanine cores are planar. Their H-Npy bond lengths increase during deprotonation/dehydrogenation of the central ring. Due to H-Npy bonds, the C4 symmetry axis can be observed only in 2[dmaphPc]- and 1[dmaphPc]2-.

2.3. Electronic Structure

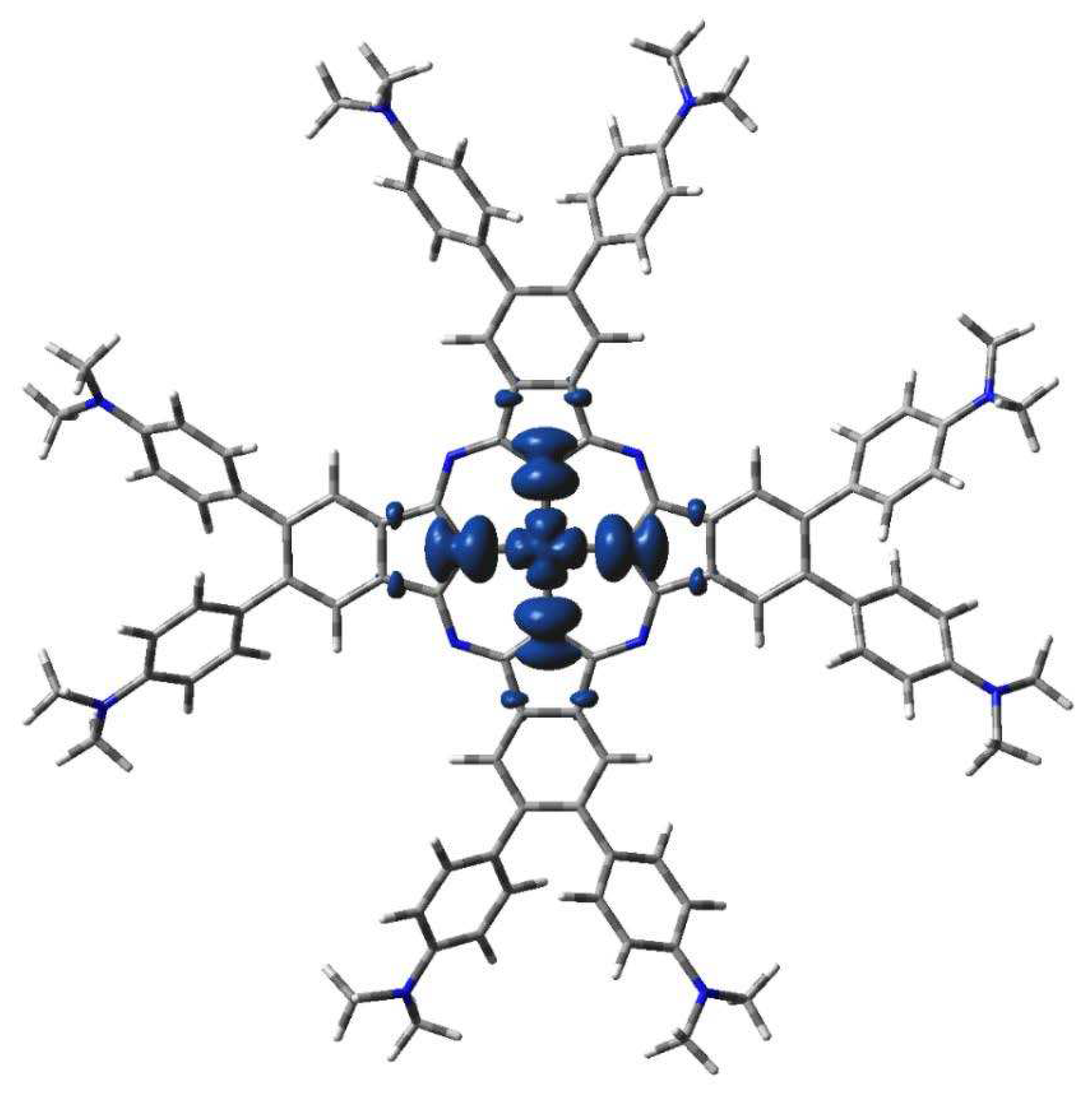

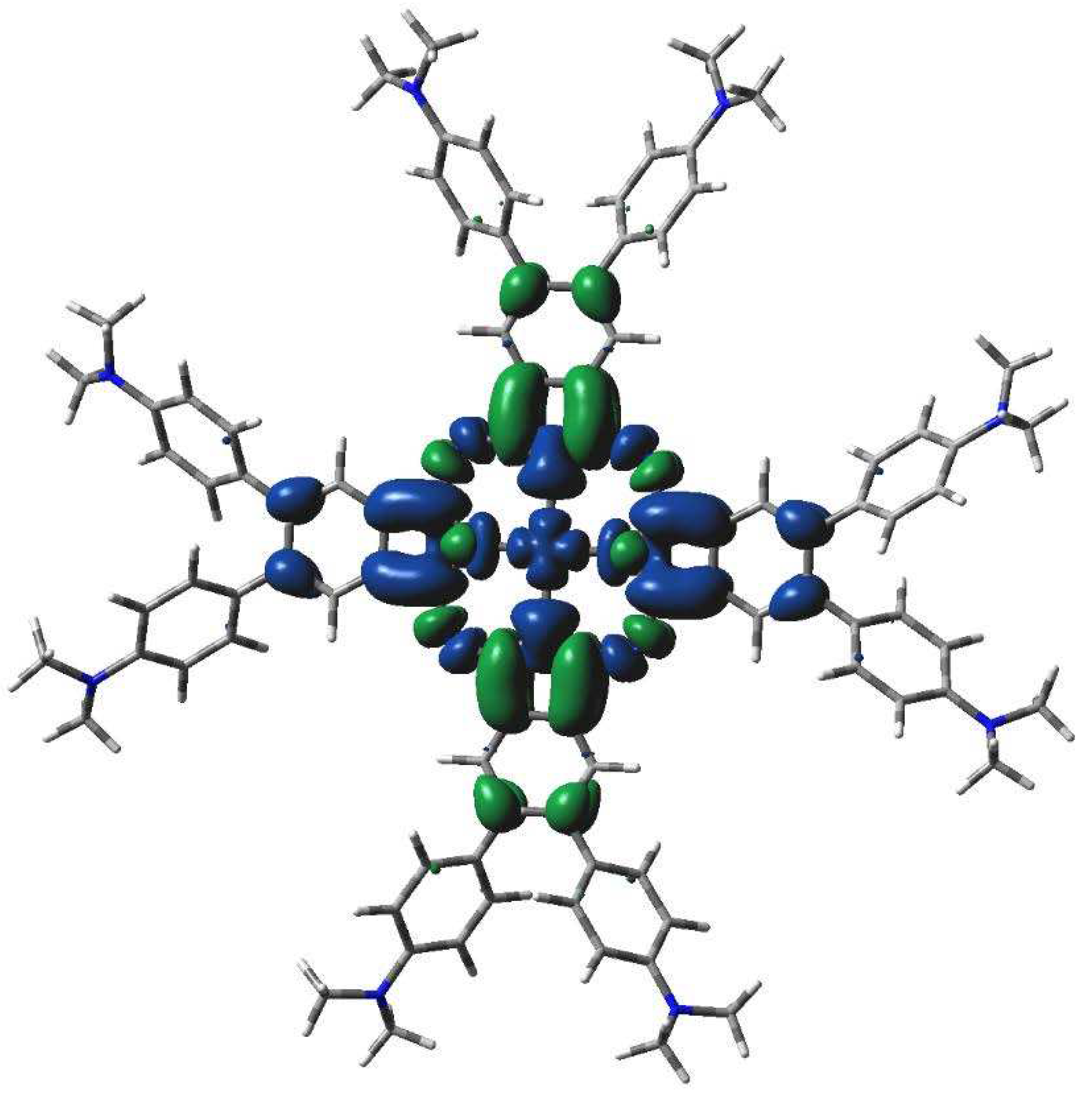

The main features of the m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes are presented in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figures S3–S5 and Table 2. Their Ag – Npy bond orders and positive Ag charges decrease upon reduction up to [dmaphPcAg]-. Except for complexes in singlet spin states, the d-electron populations of silver atoms are practically constant. The atomic charges of the pyrrole nitrogens Npy are more negative than that of the bridging nitrogens Nbr, and the amine nitrogens Namin have even less negative charges. During reduction of the complex, all N charges become even more negative. Positive charges of carbon atoms at the 4- and 7-positions of the isoindole units denoted as Cα decrease with reduction of the complex. Similarly, small negative charges of carbon atoms at isoindoles 5- and 6-positions denoted as Cβ increase with reduction of the complex. Significantly more negative charges of the Cmet methyl carbons do not depend on the charge q and spin state m of the m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes. Only Namin and Cmet charges are not affected by the lower symmetry of the complexes studied.

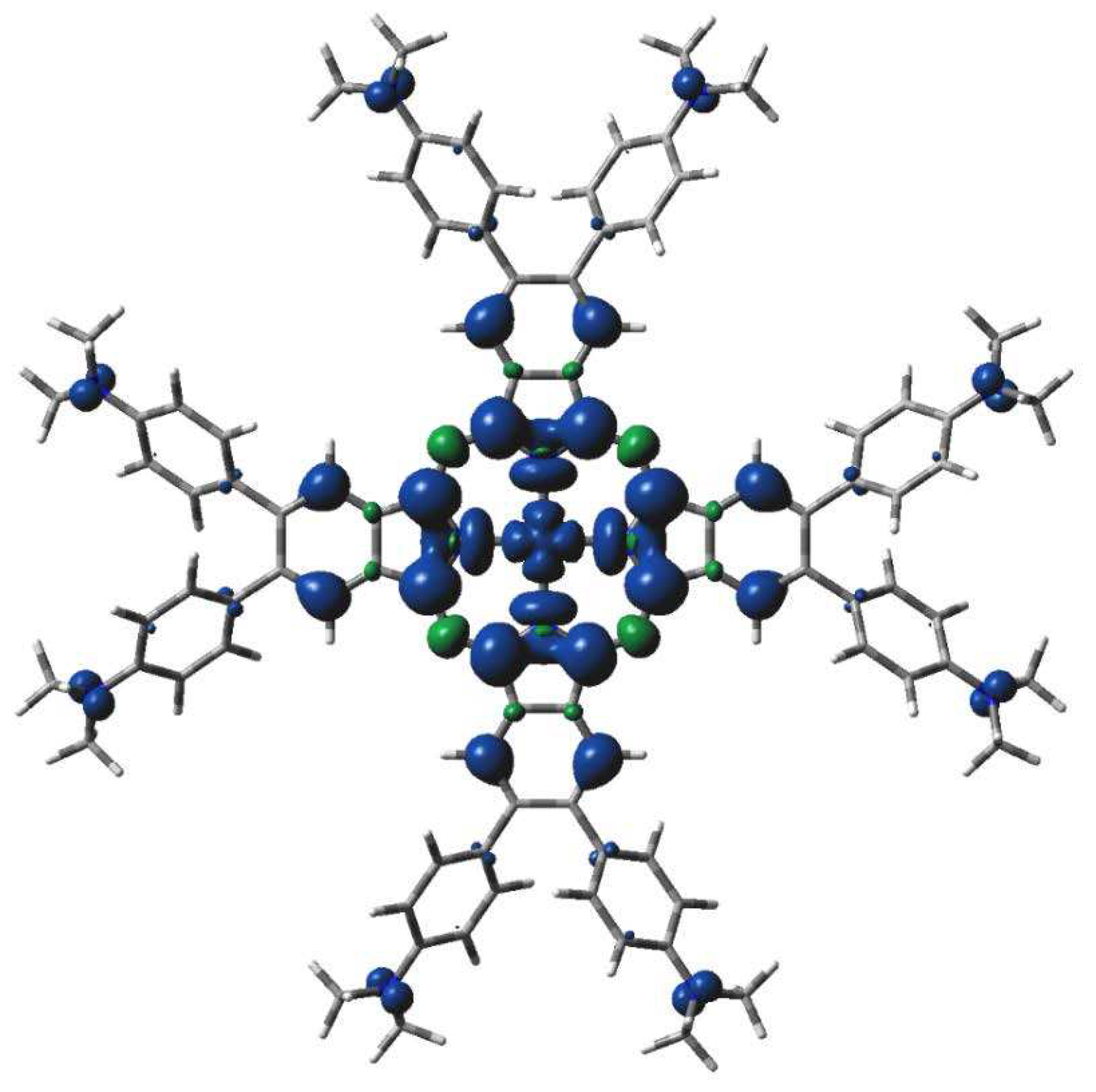

The highest spin density at Ag atoms decreases only slightly with reduction. Npy atoms have ca two - three times lower spin density of the same sign, which rises with reduction. In both cases, the spin density increases with spin multiplicity. Except for 4[dmaphPcAg]2-, the spin density of opposite sign at Nbr atoms is about one order lower and of variable signs. The spin density at Cα atoms is relevant only in anionic complexes and in higher spin states. Cβ atoms have even lower spin density. The spin density at Namin and Cmet atoms is vanishing. Only the Nbr, Namin and Cmet charges are not affected by the lower symmetry of the complexes under study. Except for 3[dmaphPcAg]+, only vanishing spin density can be found in dimethylaminophenyl groups.

The main features of the m[dmaphPcHn]q species are presented in Figures S6 and S7, and Table 3. The H – Npy bond orders decrease with dehydrogenation/deprotonation. The same trend exhibits the most negative Npy charges, whereas the Nbr ones exhibit a reverse trend. The even less negative Namin charges increase with the negative charge of the whole species. The positive Cα charges decrease with the total charge of the species and increase with deprotonation/dehydrogenation. Only small changes in the very small Cβ charges can be observed. Negative Cmet charges are constant in all m[dmaphPcHn]q species under study and equal to those of m[dmaphPcAg]q.

We have only two 2[dmaphPcHn]q species with non-zero spin. The small spin densities at the Npy and Nbr atoms are of the same sign, unlike the higher ones at Cα atoms. The vanishing spin density is at Cβ and Namin atoms. No spin density at Cmet atoms can be observed.

2.4. Electron Transitions

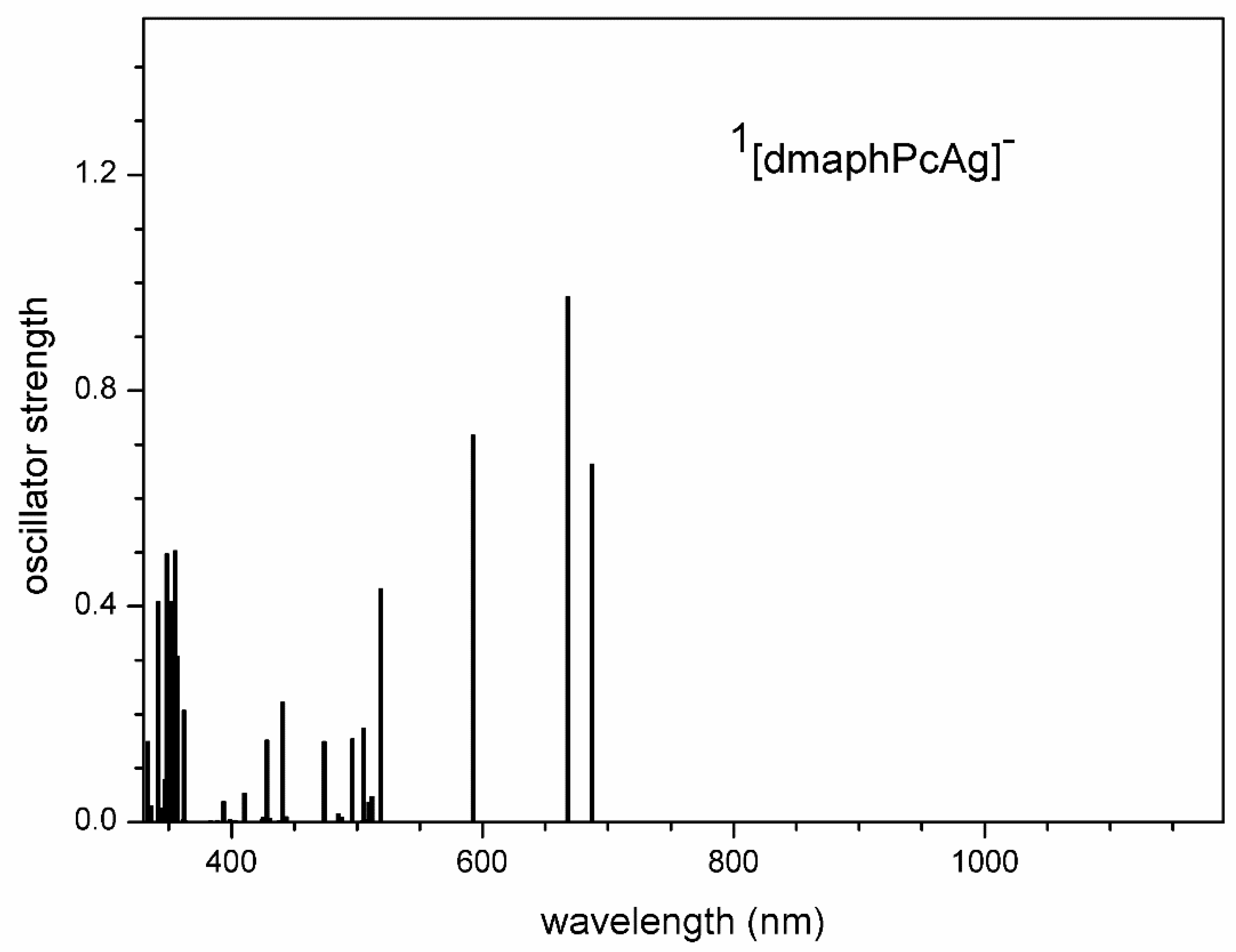

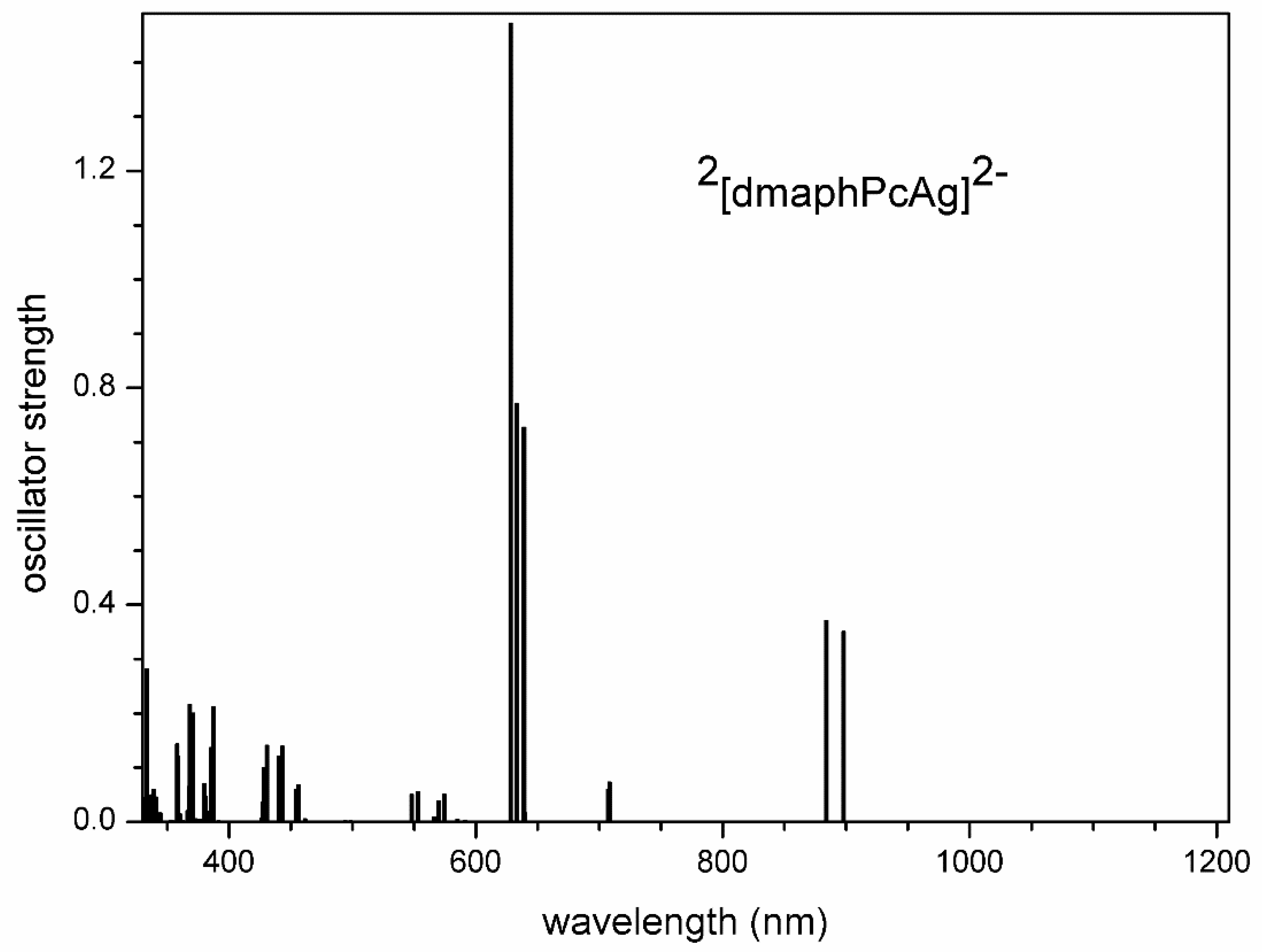

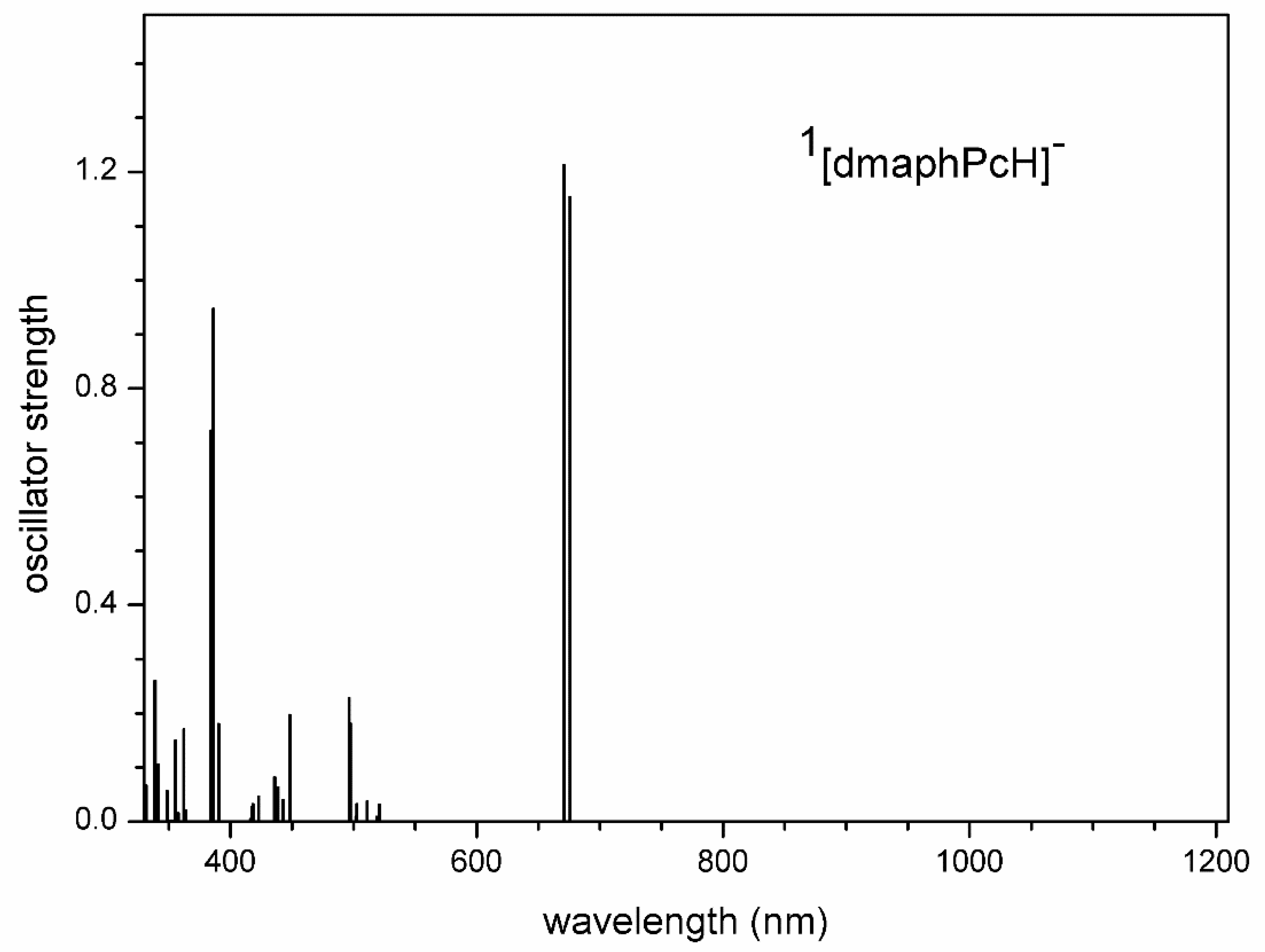

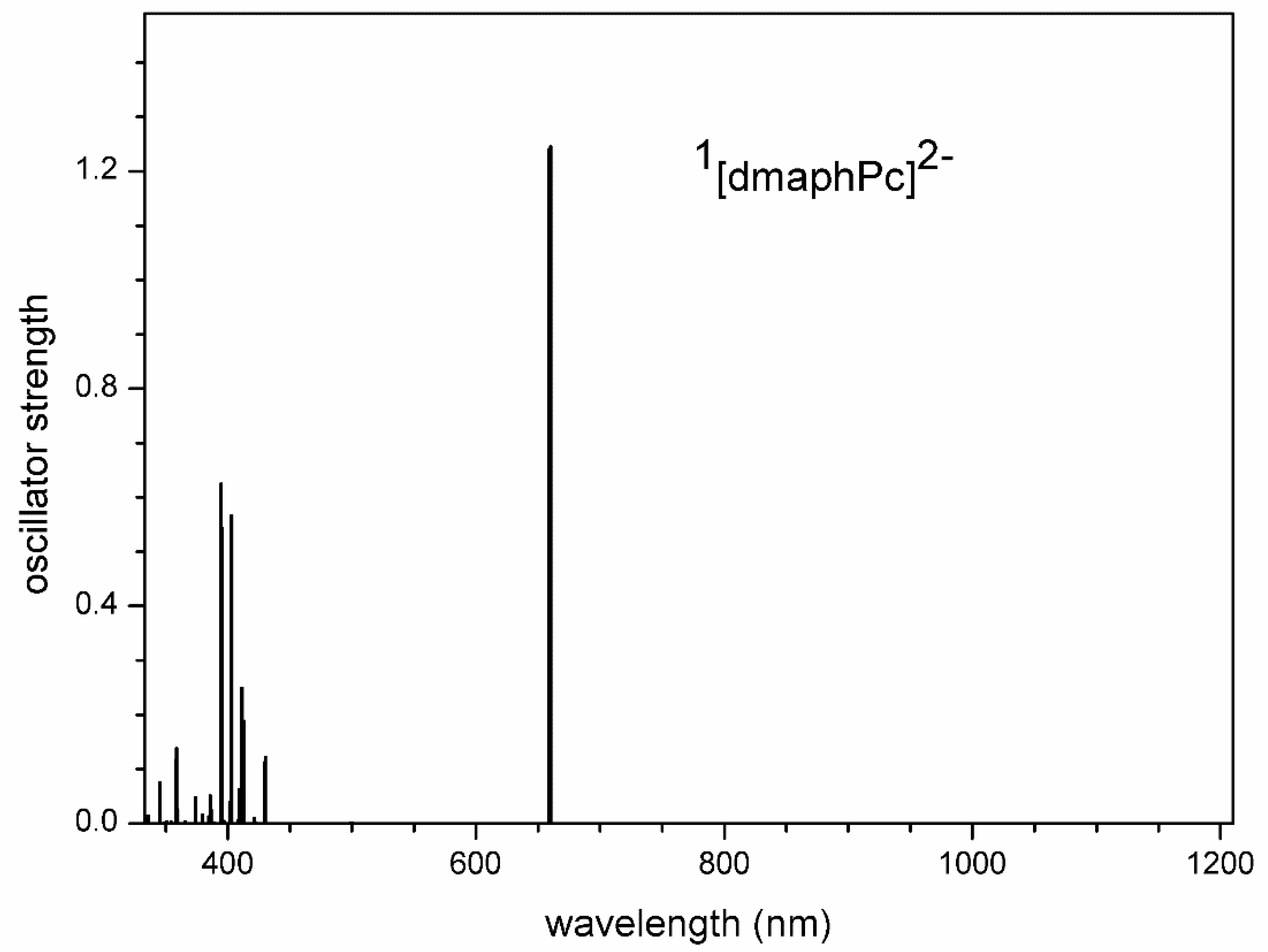

In this section we will compare the TD-DFT calculated electron transitions of m[dmaphPcAg]q complexes in CHCl3 (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figures S8–S11) with UV-vis spectra of in [dmaphPcAg]0 in CHCl3 before (Figure 2) and during (Figure 4) photolysis.

Very intense TD-DFT electron transitions of 2[dmaphPcAg]0 at 723 and 724 nm (Figure 10) can be assigned rather to the 730 nm shoulder than to the 700 nm peak in experimental spectra (Figure 2). Similarly, the intense electron transitions at 359 nm correspond more probably to the experimental peak at 360 nm than at 300 nm. It implies the existence of several species in the solution.

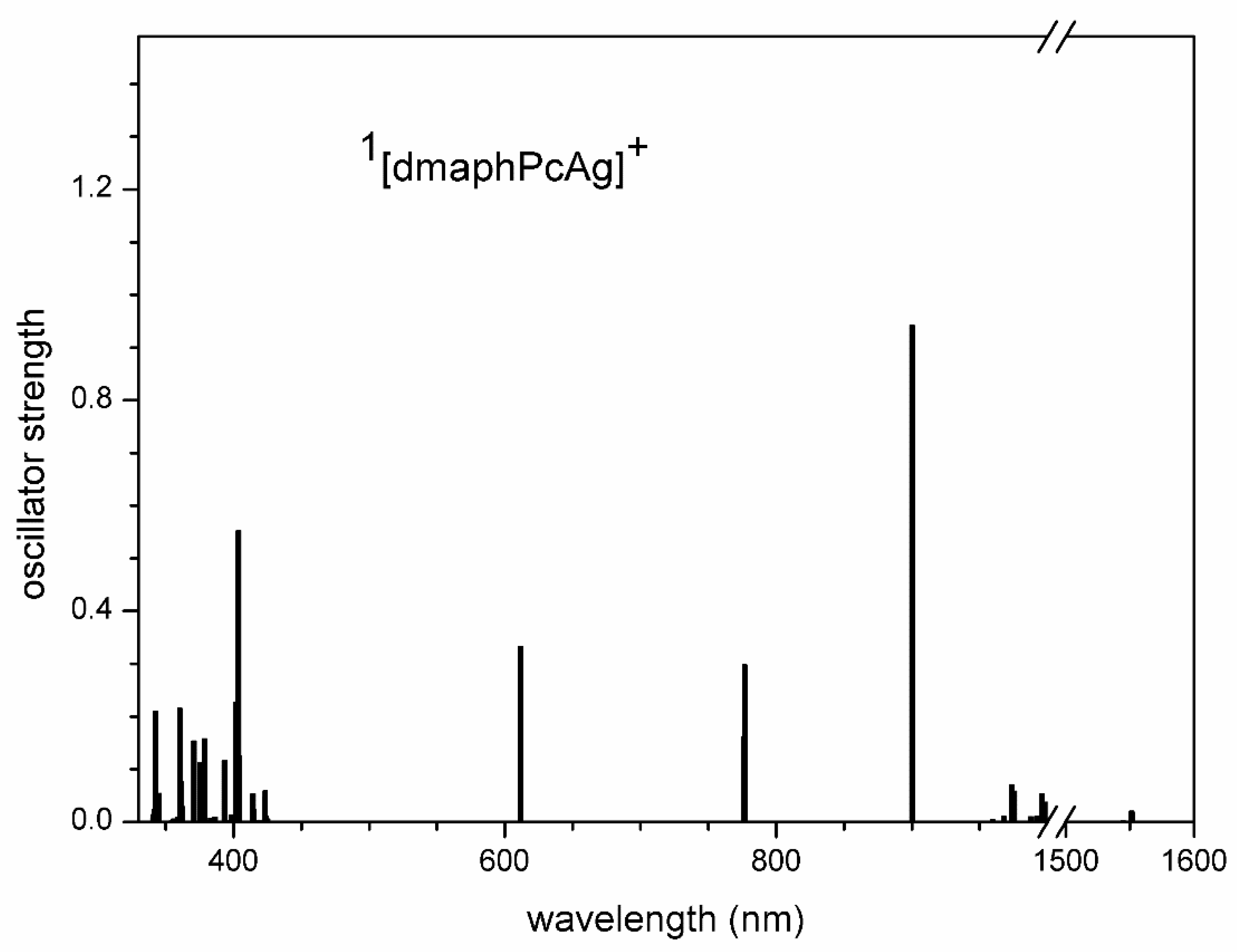

Intense electron transitions of 3[dmaphPcAg]+ calculated at 2390 nm, as well as less intense ones at 915 and 856 nm (Figure 11) are not observed in the experimental spectra of the reaction system in Figure 4. This excludes its presence at measurable concentrations. The same holds for 1[dmaphPcAg]+ due to the very intense TD-DFT electron transition at 900 nm (Figure S8), which is absent in the experimental spectra (Figure 4). Analogously, the calculated relevant electron transitions of 4[dmaphPcAg]0 at 1276 and 1210 nm (Figure S9) missing in experimental spectra are in contradiction with the presence of this species in the reaction system (Figure 4).

On the other hand, the experimental peak at 680 nm can be assigned to an intense electron transition at 687 nm and the 660 nm peak to an intense 668 nm transition whereas the 593 nm electron transition might correspond to its shoulder. This supports the presence of 1[dmaphPcAg]- in the reaction system (Figure 4 and Figure 12). The presence of 3[dmaphPcAg]- in the reaction system cannot be excluded because the experimental peak at 730 nm (Figure 4) can be explained as the very intense TD-DFT electron transition at 724 nm and the very intense electron transition at 619 nm (Figure S10) can be superimposed by the scarcely visible shoulder of the very intense peak at 700 nm.

The absence of 2[dmaphPcAg]2- in the reaction system is due to the missing experimental peaks corresponding to the relevant electron transitions at 898 nm and 884 nm (Figure 4 and Figure 13). Analogously, the absence of experimental peaks corresponding to the TD-DFT electron transitions of 4[dmaphPcAg]2- at 1153 nm and 812 nm (Figure 4 and Figure S11) is the reason for the exclusion of this species from the reaction system.

Very intense TD-DFT electron transitions of 1[dmaphPcH2]0 at 736 and 749 nm (Figure 14) can be assigned to the 750 nm peak in the experimental spectra (Figure 2). Similarly, the experimental peak at 340 nm can be explained by the calculated electron transitions at 358 nm and 364 nm. Therefore, the agreement between the experimental and calculated spectral parameters is worse than in the case of 2[dmaphPcAg]0.

Very intense TD-DFT electron transitions of 1[dmaphPcH]- at 675 nm and 671 nm (Figure 15) can be assigned to the experimental peak at 680 nm (Figure 4). The experimental peak at 380 nm can be explained by the very intense calculated electron transitions at 386 and 384 nm. Its neutral analogue 2[dmaphPcH]0 can be excluded from the reaction system due to missing experimental peaks corresponding to TD-DFT electron transitions at 1183 nm, 1154 nm, 832 nm, and 788 nm (Figure 4 and Figure S12).

The very intense calculated electron transitions of 1[dmaphPc]2- at 660 nm and 658 nm (Figure 16) can be assigned to the 660 nm or 680 nm shoulder (but not to both) of the 730 nm peak shoulder in the reaction spectra (Figure 4). TD-DFT electron transitions of 2[dmaphPc]- at 778 nm and 777 nm (Figure S13) can also be superimposed by the intense 730 nm peak shoulder of the reaction system Figure 4) and this peak can be assigned to very intense 722 nm and 721 nm electron transitions, too.

We can conclude that our TD-DFT interpretation of the experimental UV-vis spectra indicates that the 2[dmaphPcAg]0, 1[dmaphPcAg]-, 3[dmaphPcAg]-, 1[dmaphPcH2]0, 1[dmaphPcH]-, 2[dmaphPc]-, and 1[dmaphPc]2- species can be present in the reaction system under study.

3. Discussion

Two- or even three-electron reduction of the 3[dmaphPc]+ species causes only small changes in the electron and spin population at the central Ag atom, and the same holds for the Ag-Npy bond. The added electrons are prevailingly distributed on the dmaphPc2- ligand only which is typical for ‘non-innocent’ ligands. This reduction does not cause a shift of Ag from the phthalocyanine plane. However, neutral Ag nanoparticles should be formed within the endothermic reaction (3) which is connected with ca. 0.8 electron addition to Ag simultaneously with its move from the ligand plane. The planarity of the phthalocyanine core of 2[dmaphPc]- is preserved. These changes should proceed in several reaction steps including the aggregation of the [dmaphPcAg]- species in the solution. However, this does not coincide with its negative charge.

The results of our ‘broken symmetry’ DFT calculations indicate the nonexistence of singlet biradicals. According to the energy data, the 3[dmaphPcAg]+ concentration should dominate over their singlet counterparts, but the UV-vis spectra [23] do not confirm its presence in reaction systems. Based on EPR measurements using spin traps [23], this can be explained by the very low stability of 3[dmaphPcAg]+. Moreover, only this species has non-vanishing spin density at Namin atoms (see Figure 7) as supposed in [23]. The calculated electron transitions of the EPR silent 1[dmaphPcAg]+ species do not agree with UV-vis spectra [23] and so it is not present in reaction solutions.

The presence of 2[dmaphPcAg]0 in reaction solutions is in agreement with the DFT and TD-DFT calculations as well as with the EPR and UV-vis measurements [23]. However, the calculated electron transitions cannot explain all the spectral peaks in Figure 2. This indicates the presence of other species in the CHCl3 solution of 2[dmaphPcAg]0. The comparison of UV-vis spectra with the TD-DFT electron transition as well as the DFT energy data indicate the absence of 4[dmaphPcAg]0 in reaction solutions.

The coexistence of 1[dmaphPcAg]- and 3[dmaphPcAg]- in reaction solutions is allowed by their energies and by the agreement of the calculated electron transitions with UV-vis spectra [23]. 1[dmaphPcAg]- is EPR silent.

Energy data indicate that the concentration of 2[dmaphPcAg]2- should dominate over 4[dmaphPcAg]2- but the calculated electron transitions of both species do not agree with UV-vis spectra [23], implying their absence in reaction solutions.

Based on TD-DFT electron transitions and UV-vis spectra [23], the EPR silent 1[dmaphPcH2]0 species and its deprotonated products 1[dmaphPc]- and 1[dmaphPc]2- can be present in reaction solutions. The same holds for the dehydrogenated product 2[dmaphPc]- but not for 2[dmaphPcH]0.

4. Methods

Standard B3LYP [26] geometry optimization with Grimme’s GD3 dispersion correction [27] of m[dmaphPcAg]q, q = -2 to +1, in two lowest spin states m, and m[dmaphPcHn]q , n = 2 to 0, q = 0, 1, or 2, in the lowest spin states m, in CHCl3 solutions using the cc-pVDZ-PP pseudopotential and basis set for Ag [28] and cc-pVDZ basis sets for the remaining atoms [29] was performed. All calculations were carried out using an unrestricted formalism within ‘broken symmetry’ treatment [25]. Solvent effects were approximated by the SMD (Solvation Model based on solute electron Density) modification [30] of the integral equation formalism polarizable continuum model. The optimized structures were tested on the absence of imaginary vibrations by vibrational analysis. The excited state energies and the intensities of the corresponding electron transitions were evaluated using the time-dependent DFT method (TD-DFT) [31] for 90 - 120 states. The electronic structure was evaluated in terms of Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) population analysis [32]. All calculations were performed using the Gaussian16 [33] program package.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to supplement the quantum-chemical studies related to the [dmaphPcAg] photoinitiator of polymerization reactions in [23]. We tested the initial steps (1) – (3) of FRP proposed in [23] by (TD-)DFT interpretation of the EPR and UV-vis measurements by testing the presence of possible reaction intermediates m[dmaphPcAg]q, q = 1 → -2, 1[dmaphPcH2]0, and its deprotonation/dehydrogenation products.

Our results suggest the presence of crucial unstable 3[dmaphPcAg]+ species which was deduced by EPR spin trap experiments [23], but its identification was complicated due to the presence of other similar compounds in reaction solutions.

In addition to 2[dmaphPcAg]0, our results suggest the coexistence of both 1[dmaphPcAg]- (EPR silent) and 3[dmaphPcAg]- species in reaction solutions as well. Therefore, the supposed intermediates of the reactions (1) – (3) can be identified. The presence of the EPR silent species 1[dmaphPcH2]0, 1[dmaphPc]- and 1[dmaphPc]2- as well as of the radical 2[dmaphPc]- in reaction solutions cannot be excluded.

However, the formation of Ag nanoparticles by reaction (3) may be a weak point of the proposed reaction mechanism from the energetic, stereochemistry, and electronic structure points of view. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient information to propose any alternative reaction mechanisms. Further experimental and theoretical studies are desirable in this field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figures S1 – S2. DFT optimized structures of 2[dmaphPcH]0 and 2[dmaphPc]- in CHCl3. Figures S3 – S7. DFT calculated spin density of 4[dmaphPcAg]0, 3[dmaphPcAg]- , 4[dmaphPcAg]2-, 2[dmaphPcH]0, and 2[dmaphPc]- in CHCl3. Figures S8 – S13. TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 1[dmaphPcAg]+, 4[dmaphPcAg]0, 3[dmaphPcAg]-, 4[dmaphPcAg]2-, 2[dmaphPcH]0, and 2[dmaphPc]- in CHCl3.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency (project no. APVV-19-0087), by the Slovak Scientific Grant Agency VEGA (project no. 1/0175/23), and by Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic within the scheme “Excellent research teams”. The author thanks the HPC center at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, which is a part of the Slovak Infrastructure of High Performance Computing (SIVVP project ITMS 26230120002, funded by European Region Development Funds) for the computational time and resources made available.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Urbani, M.; Ragoussi, M.-E.; Nazeeruddin, M. K.; Torres, T. Phthalocyanines for dye-sensitized solar cells. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 381, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliya, O. L.; Lukyanets, E. A.; Vorozhtsov, G. N. Catalysis and Photocatalysis by Phthalocyanines for Technology, Ecology, and Medicine. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 1999, 3, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A. B. Phthalocyanine Metal Complexes in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 8152–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juzenas, P. Lasers in Therapy of Human Diseases. Trends Cancer Res. 2005, 1, 93−110.

- O’Riordan, K.; Akilov, O. E.; Hasan, T. The Potential for Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Localized Infections. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2005, 2, 247−262. [CrossRef]

- Sekkat, N.; van den Bergh, H.; Nyokong, T.; Lange, N. Like a Bolt from the Blue: Phthalocyanines in Biomedical Optics. Molecules 2012, 17, 98−144. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C. M.; Sharman, W. M.; Van Lier, J. E. Current Status of Phthalocyanines in the Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2001, 5, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanets, E. A. Phthalocyanines as Photosensitizers in the Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 1999, 3, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R. N.; Cunha, A.; Tomé, A. C. Phthalocyaninesulfonamide Conjugates: Synthesis and Photodynamic Inactivation of Gram-negative and Gram-positive Bacteria. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 154, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elemans, J. A. A. W.; van Hameren, R.; Nolte, R. J. M.; Rowan, A. E. Molecular Materials by Self-assembly of Porphyrins, Phthalocyanines, and Perylenes. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gsaenger, M.; Bialas, D.; Huang, L.; Stolte, M.; Wuerthner, F. Organic Semiconductors Based on Dyes and Color Pigments. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3615–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A. L.; Delile, S.; Brunet, J.; Varenne, C.; Pauly, A. Electrochemical Sensors Based on Screen-printed Electrodes: The Use of Phthalocyanine Derivatives for Application in VFA Detection. Biosensors-Basel 2016, 6, 0046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lv, W.; Luo, X.; He, L.; Xu, K.; Zhao, F.; Huang, F.; Lu, F.; Peng, Y. A Comprehensive Investigation of Organic Active Layer Structures Toward High Performance Near-infrared Phototransistors. Synth. Met. 2018, 240, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woehrle, D.; Schnurpfeil, G.; Makarov, S. G.; Kazarin, A.; Suvorova, O. N. Practical Applications of Phthalocyanines – from Dyes and Pigments to Materials for Optical, Electronic and Photoelectronic Devices. Makrogeterotsikly 2012, 5, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, G.; Vazquez, P.; Agullo-Lopez, F.; Torres, T. Phthalocyanines and Related Compounds: Organic Targets for Nonlinear Optical Applications. J. Mater. Chem. 1998, 8, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hanack, M.; Blau, W. J.; Dini, D.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Bai, J. Soluble Axially Substituted Phthalocyanines: Synthesis and Nonlinear Optical Response. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 2169–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, D.; Dudkowiak, A. Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines − Functional Molecular Materials for Optoelectronics and Medicine. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2006, 448, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jung, K.; Boyer, C. Effective Utilization of NIR Wavelengths for Photo-Controlled Polymerization: Penetration Through Thick Barriers and Parallel Solar Syntheses. Angew. Chem. 2020, 59, 2013–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, N.; Xu, J.; Boyer, C. A Photoinitiation System for Conventional and Controlled Radical Polymerization at Visible and NIR Wavelengths. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, S. E.; Temel, G.; Balta, D. K.; Arsu, N.; Şener, M. K. Type II photoinitiator substituted zinc phthalocyanine: Synthesis, photophysical and photopolymerization studies. J. Lumin. 2013, 136, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breloy, L.; Brezová, V.; Blacha-Grzechnik, A.; Presset, M.; Yildirim, M. S.; Yilmaz, I.; Yagci, Y.; Versace, D.-L. Visible Light Anthraquinone Functional Phthalocyanine Photoinitiator for Free-Radical and Cationic Polymerizations. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, B.; Shi, R.; Pan, L.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, F.; Xie, A. Preparation and characterization of a novel hybrid hydrogel shell for localized photodynamic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 6411–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breloy, L.; Alcay, Y.; Yilmaz, I.; Breza, M., Bourgon, J.; Brezová, V.; Yagci, Y., Versace, D.-L. Dimethyl amino phenyl substituted silver phthalocyanine as a UV- and visible-light absorbing photoinitiator: in situ preparation of silver/polymer nanocomposites. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 1273-1285. [CrossRef]

- Breza, M. On the Jahn–Teller Effect in Silver Complexes of Dimethyl Amino Phenyl Substituted Phthalocyanine. Molecules 2023, 28, 7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noodleman, L. Valence bond description of antiferromagnetic coupling in transition metal dimer. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 5737–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parameterization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, B.P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T.D.; Windus, T.L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunning, T.H., Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.; Cramer, C.; Truhlar, D. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 256, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. P.; Weinhold, F. Natural Hybrid Orbitals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7211–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016.

Figure 1.

DFT optimized structure of 2[dmaphPcAg]0 in CHCl3 (C – black, N – blue, Ag – green, H – white) [23].

Figure 1.

DFT optimized structure of 2[dmaphPcAg]0 in CHCl3 (C – black, N – blue, Ag – green, H – white) [23].

Figure 2.

UV-vis spectra of neutral dmaphPcAg (full line) and dmaphPcH2 (dashed line) in CHCl3 [23].

Figure 2.

UV-vis spectra of neutral dmaphPcAg (full line) and dmaphPcH2 (dashed line) in CHCl3 [23].

Figure 3.

DFT optimized structure of 1[dmaphPcH2]0 in CHCl3 (C – black, N – blue, H – white).

Figure 4.

Time dependence of absorption spectra during photolysis of (A) [dmaphPcAg]0 and (B) [dmaphPcAg]0/Iod under LED@385 nm irradiation. LED@385 nm intensity = 470 mW cm−2. Concentration of Iod = 7.9 × 10−5 M, concentration of [dmaphPcAg]0 = 3.8 × 10−5 M. Solvent = CHCl3 [23].

Figure 4.

Time dependence of absorption spectra during photolysis of (A) [dmaphPcAg]0 and (B) [dmaphPcAg]0/Iod under LED@385 nm irradiation. LED@385 nm intensity = 470 mW cm−2. Concentration of Iod = 7.9 × 10−5 M, concentration of [dmaphPcAg]0 = 3.8 × 10−5 M. Solvent = CHCl3 [23].

Figure 5.

DFT optimized structure of 1[dmaphPcH]- in CHCl3 - above (top) and side (bottom) views (C – black, N – blue, H – white).

Figure 5.

DFT optimized structure of 1[dmaphPcH]- in CHCl3 - above (top) and side (bottom) views (C – black, N – blue, H – white).

Figure 6.

DFT optimized structure of 1[dmaphPc]2- in CHCl3 (C – black, N – blue, H – white).

Figure 7.

DFT calculated spin density of 3[dmaphPcAg]+ in CHCl3 (0.001 a.u. isosurface).

Figure 8.

DFT calculated spin density of 2[dmaphPcAg]0 in CHCl3 (0.001 a.u. isosurface).

Figure 9.

DFT calculated spin density of 2[dmaphPcAg]2- in CHCl3 (0.001 a.u. isosurface).

Figure 10.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 2[dmaphPcAg]0 in CHCl3.

Figure 11.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 3[dmaphPcAg]+ in CHCl3.

Figure 12.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 1[dmaphPcAg]- in CHCl3.

Figure 13.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 2[dmaphPcAg]2- in CHCl3.

Figure 14.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 1[dmaphPcH2]0 in CHCl3.

Figure 15.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 1[dmaphPcH]- in CHCl3.

Figure 16.

TD-DFT calculated electron transitions in 1[dmaphPc]2- in CHCl3.

Table 1.

Absolute (G298) and relative (ΔG298) Gibbs free energies at 298 K of m[dmaphPcAg]q and m[dmaphPcHn]0 species in CHCl3 under study, n = 2→0, in various charge (q) and spin (m) states.

Table 1.

Absolute (G298) and relative (ΔG298) Gibbs free energies at 298 K of m[dmaphPcAg]q and m[dmaphPcHn]0 species in CHCl3 under study, n = 2→0, in various charge (q) and spin (m) states.

| Compound | q | m | G298 [Hartree] | ΔG298 [kJ/mol] |

| 1[dmaphPcAg]+ | +1 | 1 | -4733.24222 | 453.4 |

| 3[dmaphPcAg]+ | +1 | 3 | -4733.25119 | 429.9 |

| 2[dmaphPcAg]0 | 0 | 2 | -4733.41492 | 0.0 |

| 4[dmaphPcAg]0 | 0 | 4 | -4733.38011 | 91.4 |

| 1[dmaphPcAg]- | -1 | 1 | -4733.51744 | -269.2 |

| 3[dmaphPcAg]- | -1 | 3 | -4733.51527 | -263.5 |

| 2[dmaphPcAg]2- | -2 | 2 | -4733.59008 | -459.9 |

| 4[dmaphPcAg]2- | -2 | 4 | -4733.57970 | -432.6 |

| 1[dmaphPcH2]0 | 0 | 1 | -4587.58495 | 0.0 |

| 1[dmaphPcH]- | -1 | 1 | -4587.08582 | 1310.5 |

| 2[dmaphPcH]0 | 0 | 2 | -4586.94941 | 1668.6 |

| 1[dmaphPc]2- | -2 | 1 | -4586.54403 | 2732.9 |

| 2[dmaphPc]- | -1 | 2 | -4586.43712 | 3013.6 |

Table 2.

Relevant geometric and electronic structure parameters of the m[dmaphPcAg]q systems in CHCl3 (see Table 1) related to the central Ag, pyrrole Npy, bridging Nbr, aminyl Namin, methyl Cmet and isoindole C atoms in 4-, 7- (Cα) and 5-, 6- (Cβ) positions (adj = adjacent, op = opposite bond angles).

Table 2.

Relevant geometric and electronic structure parameters of the m[dmaphPcAg]q systems in CHCl3 (see Table 1) related to the central Ag, pyrrole Npy, bridging Nbr, aminyl Namin, methyl Cmet and isoindole C atoms in 4-, 7- (Cα) and 5-, 6- (Cβ) positions (adj = adjacent, op = opposite bond angles).

| q | +1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | -2 | -2 |

| m | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Bond length [Å] | ||||||||

| Ag-Npy | 2.000(4×) | 2.056(4×) | 2.059(4×) | 2.058(2×) 2.062(2×) |

2.067(2×) 2.133(2×) |

2.063(2×) 2.067(2×) |

2.072(4×) | 2.071(4×) |

| Ag – plane distance [Å] | ||||||||

| Npy plane | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Bond angle [deg] | ||||||||

| (Npy-Ag-Npy)adj | 90.0(4×) | 90.0(4×) | 90.0(4×) | 90.0(4×) | 89.9(2×) 90.1(2×) |

90.0(4×) | 90.0(4×) | 90.0(4×) |

| (Npy-Ag-Npy)op | 179.9(2×) | 178.9(2×) | 179.7(2×) | 180.0(2×) | 179.2 179.5 |

180.0(2×) | 180.0(2×) | 180.0(2×) |

| Bond order | ||||||||

| Ag-Npy | 0.448(4×) | 0.377(4×) | 0.379(4×) | 0.379(2×) 0.377(2×) |

0.363(2×) 0.330(2×) |

0.382(2×) 0.381(2×) |

0.383(4×) | 0.384(4×) |

| Charge | ||||||||

| Ag | 1.023 | 0.857 | 0.843 | 0.833 | 0.713 | 0.814 | 0.787 | 0.785 |

| Npy | -0.574(4×) | -0.623(4×) | -0.614(4×) | -0.613(2×) -0.662(2×) |

-0.637(2×) -0.614(2×) |

-0.603(2×) -0.647(2×) |

-0.633(2×) -0.637(2×) |

-0.634(4×) |

| Nbr | -0.533(4×) | -0.553(4×) | -0.550(4×) | -0.587(4×) | -0.566(4×) | -0.579(4×) | -0.617(4×) | -0.610(4×) |

| Cα |

0.497(8×) |

0.528(8×) | 0.485(8×) | 0.484(4×) 0.532(4×) |

0.464(4×) 0.435(4×) |

0.422(4×) 0.476(4×) |

0.422(8×) | 0.418(8×) |

| Cβ | -0.083(8×) | -0.092(8×) | -0.085(8×) | -0.101(4×) -0.086(4×) |

-0.083(4×) -0.091(4×) |

-0.100(4×) -0.081(4×) |

-0.101(8×) | -0.101(8×) |

| Namin | -0.482(8×) | -0.475(8×) | -0.492(8×) | -0.489(8×) | -0.497(8×) | -0.497(8×) | -0.502(8×) | -0.502(8×) |

| Cmet | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) |

| d electron population | ||||||||

| Ag | 9.23 | 9.43 | 9.43 | 9.44 | 9.58 | 9.44 | 9.45 | 9.45 |

| Spin population | ||||||||

| Ag | - | 0.426 | 0.422 | 0.426 | - | 0.420 | 0.412 | 0.415 |

| Npy | - | 0.119(4×) | 0.148(4×) | 0.080(2×) 0.206(2×) |

- | 0.120(2×) 0.234(2×) |

0.259(2×) 0.039(2×) |

0.208(4×) |

| Nbr | - | -0.037(4×) | 0.002(4×) | 0.009(4×) | - | 0.054(4×) | -0.001(4×) | 0.115(4×) |

| Cα | - | 0.086(8×) | -0.007(8×) | 0.237(4×) 0.100(4×) |

- | 0.104(4×) -0.016(4×) |

-0.106(4×) 0.096(4×) |

0.079(8×) |

| Cβ | - | -0.007(8×) | 0.006(8×) | 0.016(4×) -0.002(4×) |

- | 0.037(4×) 0.004(4×) |

-0.043(4×) 0.054(4×) |

0.047(8×) |

| Namin | - | 0.016(8×) | 0.000(8×) | 0.005(8×) | - | 0.000(8×) | 0.000(8×) | 0.001(4×) |

| Cmet | - | -0.001(16×) | 0.000(16×) | -0.000(16×) | - | 0.000(16×) | 0.000(16×) | 0.000(16×) |

Table 3.

Relevant geometric and electronic structure parameters of m[dmaphPcAg]q systems in CHCl3 (see Table 1) related to pyrrole Npy, bridging Nbr, aminyl Namin, methyl Cmet and isoindole C atoms in 4-, 7- (Cα ) and 5-, 6- (Cβ) positions.

Table 3.

Relevant geometric and electronic structure parameters of m[dmaphPcAg]q systems in CHCl3 (see Table 1) related to pyrrole Npy, bridging Nbr, aminyl Namin, methyl Cmet and isoindole C atoms in 4-, 7- (Cα ) and 5-, 6- (Cβ) positions.

| Compound | 1[dmaphPcH2]0 | 1[dmaphPcH]- | 2[dmaphPcH]0 | 1[dmaphPc]2- | 2[dmaphPc]- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q | 0 | -1 | 0 | -2 | -1 |

| m | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Bond length [Å] | |||||

| H-Npy | 1.017(2×) | 1.028 | 1.029 | - | - |

| Bond order | |||||

| H-Npy | 0.659(2×) | 0.648 | 0.645 | - | - |

| Charge | |||||

| Npy | -0.607(2×) -0.656(2×) |

-0.577 -0.613 -0.615 -0.611 |

-0.579 -0.617(2×) -0.628 |

-0.560(4×) | -0.566(4×) |

| Nbr | -0.550(4×) |

-0.571(2×) -0.565(2×) |

-0.566(2×) -0.571(2×) |

-0.588(4×) | -0.592(4×) |

| Cα | 0.488(4×) 0.475(4×) |

0.461(2×) 0.462(4×) 0.450(2×) |

0.513(2×) 0.519(2×) 0.510(2×) 0.529(2×) |

0.434(8×) | 0.500(8×) |

| Cβ | -0.084(4×) -0.090(4×) |

-0.087(2×) -0.085(4×) -0.092(2×) |

-0.094(2×) -0.089(2×) -0.097(2×) -0.086(2×) |

-0.087(8×) | -0.089(8×) |

| Namin | -0.490(4×) -0.492(4×) |

-0.497(6×) -0.495(2×) |

-0.490(2×) -0.488(4×) -0.486(2×) |

-0.503(8×) |

-0.496(8×) |

| Cmet | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.418(16×) | -0.419(16×) | -0.418(16×) |

| Spin | |||||

| Npy | - | - | -0.050 -0.042(2×) -0.023 |

- | -0.049(4×) |

| Nbr | - | - | -0.050(2×) -0.040(2×) |

- | -0.054(4×) |

| Cα | 0.125(8×) | 0.140(8×) | |||

| Cβ | -0.007(8×) | -0.002(8×) | |||

| Namin | - | - | 0.004(4×) 0.003(4×) |

- | 0.002(8×) |

| Cmet | - | - | 0.000(16×) | - | 0.000(16×) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Downloads

88

Views

22

Comments

0

Subscription

Notify me about updates to this article or when a peer-reviewed version is published.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2025 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated