1. Symptoms and Signs

Recent technological advances, including capsule endoscopy (CE) and balloon-assisted endoscopy (BAE), have revealed that small intestinal disease is more common than previously thought. Although small bowel tumors are less common than in other gastrointestinal tracts, any disease is difficult to diagnose without "suspecting" it. When the following symptoms and signs are unexplained after examination of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts, small bowel disease may be the cause.

GI bleeding

Anemia

Abdominal pain

Obstructive symptom

Body weight loss

Palpable abdominal mass

Fever of unknown origin

2. Family History

Family history is another important clue to the diagnosis of small bowel tumors because the following hereditary diseases have an increasing risk of small bowel tumors.

Lynch syndrome (HNPCC; hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer) is defined by germline mutations in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes, mostly

MLH1,

MSH2 and

MSH6. Patients with Lynch syndrome have a 100-fold increased risk of small bowel cancer compared to the general population [

1].

Patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), also known as von Recklinghausen disease, have an increased risk of developing gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) [

2].

Familial adenomatous polyposis of the colon (FAP) is a disease of autosomal dominant inheritance and is caused by a pathogenic germline variant in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. In patients with FAP, the cumulative risk of duodenal cancer is estimated at 4% at 70 years of age [

3].

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is caused by germline mutations in the serine-threonine kinase 11 (STK11) gene (formerly known as LKB1) located on chromosome 19p13.3 [

4]. The lifetime risk of developing cancers in a PJS patient ranges from 55% to 83% by age 60-70, including colon cancer (39%), pancreatic cancer (11-36%), and small bowel cancer (29%) [

5].

3. Characteristics of Each Modality for Small Intestinal Tumors

3.1. Capsule Endoscopy (CE)

CE has advantages including, high diagnostic yield, discomfort-free, outpatient basis, and physiological images.

However, CE has several disadvantages. Because the lumen is not inflated by gas insufflation, diverticula, and submucosal tumors are often missed. Lack of irrigation and aspiration capabilities makes it difficult to detect lesions if there are a lot of residues. In patients with intestinal stenosis, there is a risk of retention. When the patency of the gastrointestinal tract cannot be confirmed, CE should not be used for patients with definitive obstructive symptoms.

CE depends on peristalsis to move, so it takes at least several hours to complete the test. CE cannot evaluate the bypassed intestinal tracts or the afferent limb after Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Because CE passage is too rapid in the duodenum and the proximal jejunum, the PillCam SB3 can recognize only 42.7% of the duodenal papillae [

6]. The lesions in the duodenum and the proximal jejunum can be missed by CE.

When there are multiple similar lesions, it is difficult to distinguish each and count the lesions. CE is not suitable for counting lesions of polyposis syndromes.

Even large tumors can be missed by CE. If the CE is caught on the proximal side of a large tumor, the tumor may not be detected depending on the direction of the CE's camera. After staying for a while, the CE quickly slips through the large tumor area, and the large tumor is not captured by the CE. If the CE remains in the same location for more than 15 minutes, this is an abnormal finding known as Regional Transit Abnormality (RTA) [

7].

CE can be very useful if it is used with an understanding of the above characteristics.

3.2. Balloon-Assisted Endoscopy (BAE)

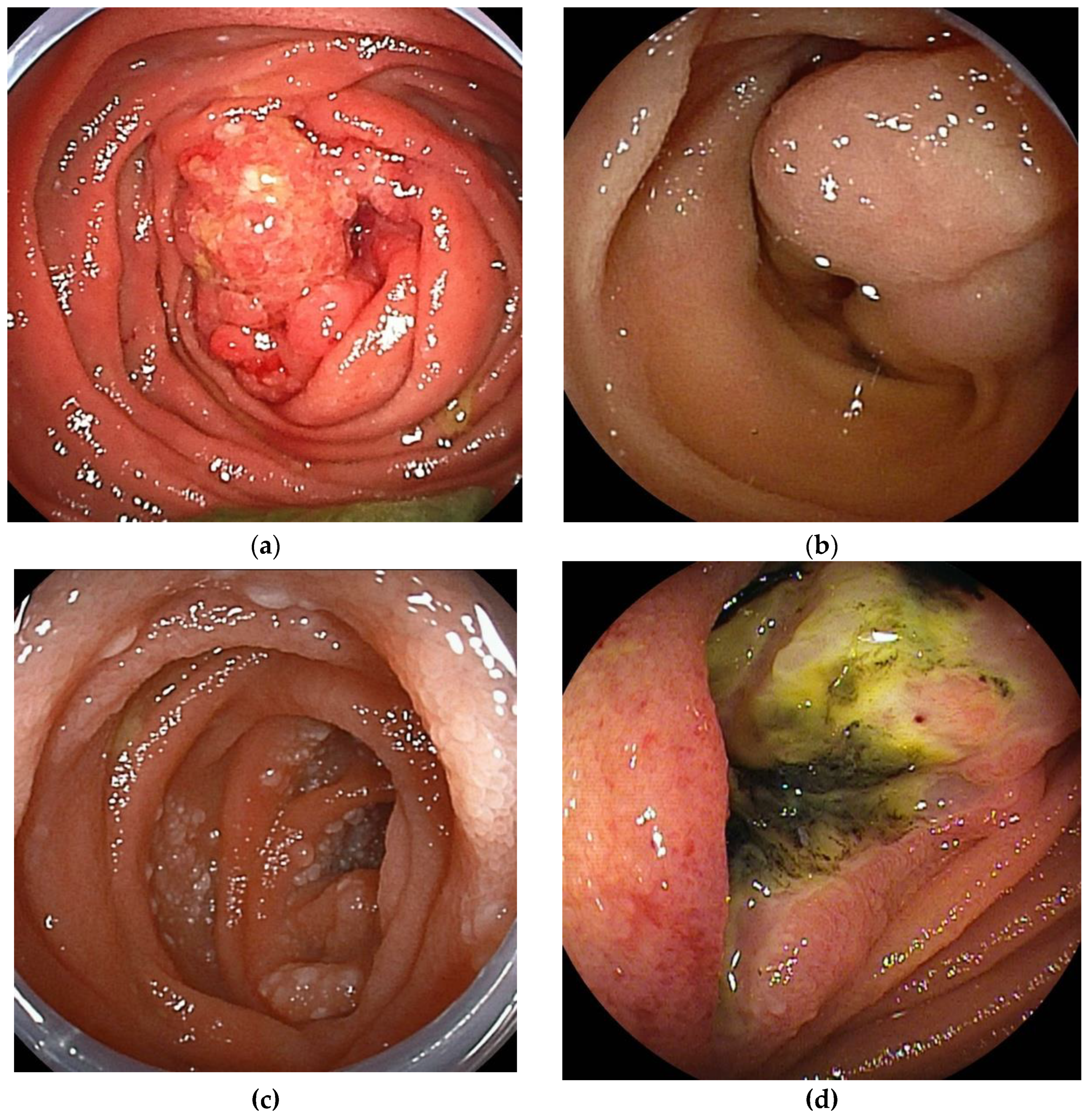

The double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) is equipped with two balloons attached at the endoscope's tip and the overtube's tip. It enabled endoscopic diagnosis (

Figure 1) and treatment in the deep small bowel. The single-balloon endoscopy (SBE), developed after DBE's launch, omits the balloon at the tip of the endoscope to simplify the preparation. Both are collectively referred to as balloon-assisted endoscopy (BAE). The BAE can be inserted with the aid of a ballooned overtube to suppress unnecessary deflection of the intestine. In addition, because the bowel is folded over the overtube, the BAE can be inserted into intestinal tracts longer than the working length of the scope. BAE can be inserted without relying on intestinal peristalsis, allowing evaluation of the afferent limb and bypassed intestinal tracts.

The BAE is equipped with a working channel that allows for procedures such as tissue biopsy, marking, and treatment. Chromoendoscopy with indigo-carmine makes it easy to detect small lesions in patients with FAP [

8]. The miniature probe can be inserted into the working channel and enables EUS evaluation for submucosal tumors [

9].

In the setting of X-ray fluoroscopy, endoscopic enteroclysis can be performed by injecting contrast through the working channel. The size and shape of the lesion can be evaluated by fluoroscopy. During endoscopic enteroclysis, the scope balloon of DBE can inflate to reduce the backflow of contrast and evaluate the wide range of the small bowel by fluoroscopy.

BAE has several disadvantages. BAE requires endoscopic skills. Severe adhesions or stenosis makes it difficult to achieve total enteroscopy with BAE. Especially near large tumors, the maneuverability may be poor due to compression and adhesions caused by the tumor, and it may not be possible to reach the lesion.

3.3. Computed Tomography (CT)

Recent technological advances have increased the usefulness of computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions. Since the introduction of MDCT (Multi detector-row CT) with 4-row detectors in 1998, the number of detectors has increased and evolved to 16-row, 64-row, and 320-row. As a result, images with high spatial resolution can be obtained in a short time over the entire abdomen. In addition to axial section, coronal and sagittal section images can be reconstructed, and multiplanar reformation (MPR) images, virtual enteroscopy, and virtual enteroclysis are also available.

CT enterography (CTE) with negative oral contrast can evaluate masses, wall thickening, and narrowing of the small intestine. In addition, Enhanced CT can detect abnormalities outside the gastrointestinal tract that cannot be evaluated by endoscopy, such as ascites, misty mesentery, lymph node swelling, and abnormal blood vessels.

Although there are problems with radiation exposure and side effects from contrast media, it is a minimally invasive test that provides a large amount of information quickly.

In diagnosing small intestinal tumors, CT is very useful in evaluating lymphadenopathy associated with malignant lymphoma and small intestinal cancer, as well as extra-luminal GIST, which is difficult to evaluate by endoscopy. However, plain CT provides a very limited amount of information and makes it difficult to detect lesions, so it is preferable to use at least contrast-enhanced CT and, if possible, Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT.

One problem with CT is that CT images are momentary images, and depending on the timing of imaging, the shape of the intestinal tract due to peristalsis or spasm may appear as a stenosis or mass. Dynamic enhanced CT can solve this problem by comparing the intestinal geometry between images taken at different times (plain, early contrast, and late contrast).

4. Diagnostic Strategy for Small Bowel Tumors

Each modality has its advantages and disadvantages, and a good combination of multiple modalities leads to an accurate diagnosis since a false negative or false positive result is possible with a single modality alone.

Honda et al reported a comparative study of the diagnostic yields of contrast-enhanced CT, fluoroscopic enteroclysis, CE, and DBE for small bowel tumors [

10]. In their comparing study, diagnostic yields for small bowel tumors </=10 mm were significantly low in contrast-enhanced CT and fluoroscopic enteroclysis. However, diagnostic yield of CE and DBE were high for small bowel tumors regardless of size. In contrast-enhanced CT, diagnostic yield of epithelial tumors was significantly lower compared with subepithelial tumors. Diagnostic yields of CE and DBE were significantly higher than that of contrast-enhanced CT, and diagnostic yield of DBE was significantly higher than that of CE. However, a combination of contrast-enhanced CT and CE had a diagnostic yield similar to that of DBE. For detecting small bowel tumors, a combination screening method using CE and contrast-enhanced CT is recommended. After the screening, DBE is useful for histologic diagnosis and endoscopic treatment.

Based on the results of the above study, we recommend the following strategies.

As a first-line modality, three-phase enhanced CT is preferred. In addition to axial images, coronal images should be produced for precise reading.

If CT shows a mass, stenosis, or wall thickening, a BAE should be selected because of its capability of biopsy and marking. The route of insertion of the BAE should be selected based on the information obtained from the CT.

If there are no abnormal findings on CT and no obstructive symptoms, CE should be selected. If there are significant findings in the CE, determine the indication for BAE and its insertion route based on these findings.

5. Role of Enteroscopy in Each Disease

5.1. Small Bowel Cancer

Most small bowel cancers arise in the duodenum to the proximal jejunum or the distal ileum. They are often found with gastrointestinal stenosis symptoms or chronic iron deficiency anemia. They often occur in the duodenum, the proximal jejunum, and the distal ileum. They can sometimes be reached with a conventional endoscope and easily reached with BAE. However, most of the patients were advanced-stage cancer at the time of diagnosis. BAE can take a biopsy for histopathologic diagnosis and mark it by tattooing for surgical treatment.

5.2. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are often caused by gastrointestinal bleeding but can also be found incidentally on contrast-enhanced CT for evaluation of other diseases.

GIST growth patterns include extraluminal, intraluminal, or mixed (dumbbell-shaped) patterns. GIST is a submucosal tumor covered by normal mucosa. Because it is difficult to distinguish from extraluminal compression, GISTs are often missed by CE. Ulcers/erosions or dilated abnormal vessels are important findings for detecting GIST using CE.

Although GIST with intraluminal and mixed patterns can be detected by BAE, GIST with extraluminal pattern is hardly detected by endoscopy, except for abnormal vessels and unnatural traction findings due to lesions.

Tattooing by BAE is helpful for identifying the lesion during laparoscopic-assisted partial resection of the small intestine.

Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) became a routine examination for evaluating gastric GIST. However, EUS-FNA is not available for small bowel GIST due to a lack of dedicated equipment. Endoscopic biopsy for GIST has a low diagnostic rate and cannot determine malignancy accurately due to their subepithelial nature [

11,

12]. Endoscopic biopsy also carries the risk of post-biopsy bleeding. The biopsy is indicated only when contrast-enhanced CT or endoscopic findings are atypical or when histopathology is necessary prior to chemotherapy for unresectable lesions.

Symptomatic GISTs, regardless of size, are indicated for surgical resection if resectable. Indication of surgical treatment for asymptomatic GISTs is determined by their size and rate of growth. Small bowel GISTs have a significantly higher metastatic risk than gastric GISTs [

13].

5.3. Malignant Lymphoma

Tissue biopsy by DBE enables histopathological diagnosis of primary small intestinal lymphoma without surgical resection. Although endoscopic findings of malignant lymphomas vary by histologic type, a definitive histopathologic diagnosis can be made by biopsy in most cases. They can be treated with chemotherapy based on the histopathologic diagnosis. But, in cases of bleeding or obstructive symptoms, chemotherapy is given after surgical treatment.

Tattooing with BAE is useful to recognize lesions during surgical treatment. Even when surgical resection is not performed, it is useful to recognize lesion sites for follow-up BAE after chemotherapy.

Endoscopic balloon dilation for post-chemotherapy stenosis is an alternative option that avoids surgical treatment [

14].

5.4. Neuroendocrine Tumor

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI NET), formerly known as carcinoids. According to the WHO classification, NETs are classified into low-grade neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs). NETs are also classified into G1, less malignant, and G2, more malignant than G1.

The secretion of serotonin and other hormones from NET can cause facial flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasm, and other symptoms known as carcinoid syndrome. The carcinoid syndrome is more frequent in NET, especially those occurring in the jejunum, ileum, and appendix, than in other gastrointestinal sites.

Multifocal NET may occur in 30-50% of patients. Patients with multiple lesions are younger than those with solitary tumors, have a significantly higher risk of developing carcinoid syndrome, and have a poorer prognosis [

15].

The endoscopic image of NET is yellowish SMT-like, but it is precisely a tumor of epithelial origin. It is often seen as an elastic, hard, mobile tumor with atrophied surface villi and dilated capillaries. Depressions, ulcers, or erosions on the surface may indicate a high-grade lesion.

Although CE may be useful in identifying NETs, CE can't confirm the correct number of multiple lesions and perform marking at the lesions.

The sensitivity of BAE for the primary SB-NET was 88%, compared to 60% for CT, 54% for MRI, and 56% for somatostatin receptor imaging. BAE could also be considered for detecting multifocal NETs before surgery. In patients who underwent small bowel resection, additional lesions were found in 54% of patients at preoperative BAE, but only 18% of patients at preoperative CE [

16].

Endoscopic resection is not recommended for jejunal and ileal NETs due to the risk of invasion and lymphatic spread, even with diminutive lesions, which may necessitate a more extensive surgical resection.

5.5. Metastatic Tumors

Metastatic tumors of the small bowel include direct invasion from other organs, intraperitoneal disseminated tumors, and metastatic tumors due to hematogenous metastasis.

Pancreatic cancer frequently directly invades the duodenum. Colon, ovary, uterus, and stomach cancers metastasize to the small intestine through direct invasion or intraperitoneal dissemination. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and malignant melanoma metastasize hematogenously to the small intestine.

The most common primary tumor for metastatic tumors in the small intestine is lung cancer.

The endoscopic image of the metastatic lesion is variable. Metastatic lesions can present as single or multiple polypoid lesions, with or without ulcers. They may be seen as a focal bowel wall thickening and cause luminal narrowing.

The management of the metastatic lesion depends on the symptoms and stage of the primary tumor. Surgical resection of the affected intestine can be useful to relieve symptoms such as obstruction and bleeding.

5.6. Benign Tumors

Many benign tumors of the small intestine are asymptomatic, making it difficult to calculate their exact prevalence. In the past, they were often found by chance during surgery or autopsy of other diseases, but with the widespread use of CE and BAE, there are more and more opportunities for diagnosis by endoscopy.

Benign small bowel tumors include adenomas, hamartomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and inflammatory fibroid polyps. The ectopic pancreas can be found as a submucosal tumor-like lesion.

In addition to sporadic lesions, there are also multiple lesions associated with polyposis syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Benign tumors can cause overt or obscure bleeding with chronic anemia. Larger tumors can cause obstructive symptoms due to narrowing of the lumen or intussusception.

5.7. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an inherited polyposis syndrome characterized by the presence of multiple hamartomatous polyps throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, excluding the esophagus. It is accompanied by mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation and an elevated lifetime risk of both GI and extra-GI malignancies [

5,

17]. PJS is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, yet around 45% of PJS patients are de novo cases. The estimated incidence has been reported up to 1/200,000 [

18].

The malignant potential of polyps is low, but the polyps can enlarge, resulting in intussusception and emergency laparotomy. Polyps can develop and grow throughout life, and repeated surgical treatment can lead to short bowel syndrome. Because intra-abdominal adhesions due to surgery can cause difficulty in total enteroscopy with BAE, the digestive tract should be examined and endoscopic treatment with BAE should be initiated before emergency laparotomy for intussusception. In patients with PJS, gastrointestinal surveillance through upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, and CE should begin by the age of 8 years old at the latest. European and Japanese guidelines recommend that SB polyps >15 mm should be treated to prevent intussusception [

19].

The conventional techniques for polyp removal in PJS are snare polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection [

20,

21]. However, these conventional techniques have a risk of complications such as perforation and bleeding. Recently, endoscopic ischemic polypectomy (EIP) has been described, which involves strangulating the stalk of polyp using a detachable snare [

22] or clips [

23] to induce polyp destruction. Performing EIP with clips is technically easier compared to conventional techniques because EIP requires visualization of only the stalk of the polyp, even within a limited working space. The advantages of EIP include the removal of a larger number of polyps and the prevention of complications after polypectomy, such as bleeding, perforation, or post-polypectomy syndrome [

24,

25]. The disadvantage of EIP is a lack of histopathological evaluation for treated polyps.

Endoscopic reduction of intussusception in patients with PJS [

26] is a viable alternative to surgery except for the patients with necrosis or perforation. The reported success rate of endoscopic reduction of 22 sites in 19 patients was 95%, with only two mild pancreatitis as adverse events [

27].

5.8. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a rare genetic predisposition primarily to digestive cancers, inherited in a dominant manner (APC gene) or recessive manner (MUTYH gene) for the main types of FAP. The definition of classical FAP is based on the presence of at least 100 colorectal adenomas [

28]. Adenomatous polyps in the duodenum are found in nearly 100% of individuals with classical APC-related FAP and in approximately 30% of patients with biallelic MUTYH mutations, and less frequently in the distal small intestine [

29]. In patients with FAP, other than colorectal cancer, duodenal cancer and desmoid tumors are significant contributors to mortality [

30].

A systematic gradient from the duodenum to the jejunum is observed, as indicated by the low risk of small bowel cancer as far as the distal small bowel is considered [

31]. Endoscopic screening for duodenal adenomas is recommended to start around 25 years old [

1,

32].

In the recent ESGE guideline, endoscopic treatment of lesions in the duodenum and jejunum has been recommended for lesions larger than 10 mm in size [

1] because of endoscopic maneuverability and the risk of complications. However, The size threshold for endoscopic resection should be optimized by weighing the risks and benefits. The feasibility and safety of performing cold snare polypectomy (CSP) for duodenal adenomas in patients with FAP were reported [

33]. CSP enabled the removal of a greater number of polyps in a shorter duration while maintaining safety [

34]. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (UEMR) [

35] for sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenoma [

36] is reported as a safe and effective procedure. These new techniques have the potential to change the size threshold for endoscopic resection. Takeuchi et al reported that intensive downstaging polypectomy using the new techniques showed significant downstaging with acceptable adverse events for multiple duodenal adenomas in patients with FAP [

37].

Each adenoma may be fused in patients with multiple adenomas and become a larger lesion. Endoscopic resection of larger adenomas may increase the risk of adverse events. At least in patients with a large number of adenomas, intensive downstaging polypectomy should be considered, even without adenomas larger than 10 mm.

6. Conclusion

Advances in various medical technologies have greatly advanced the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal diseases. However, small intestinal cancer is often found in an advanced stage. Early diagnosis of small intestinal tumors is essential for favorable outcomes. For early diagnosis, the possibility of small bowel lesions should be considered in patients with unexplained symptoms and signs after examination of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract.

Author Contributions

writing—original draft preparation, T.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Hironori Yamamoto has patents for double-balloon endoscopy and a consultant relationship with Fujifilm. Tomonori Yano has received research funding and honoraria from Fujifilm.

References

- van Leerdam, M.E.; Roos, V.H.; van Hooft, J.E.; Dekker, E.; Jover, R.; Kaminski, M.F.; Latchford, A.; Neumann, H.; Pellise, M.; Saurin, J.C.; et al. Endoscopic management of polyposis syndromes: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 877-895. [CrossRef]

- Mussi, C.; Schildhaus, H.U.; Gronchi, A.; Wardelmann, E.; Hohenberger, P. Therapeutic consequences from molecular biology for gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4550-4555. [CrossRef]

- Saurin, J.C.; Gutknecht, C.; Napoleon, B.; Chavaillon, A.; Ecochard, R.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Ponchon, T.; Chayvialle, J.A. Surveillance of duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis reveals high cumulative risk of advanced disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 493-498. [CrossRef]

- Jenne, D.E.; Reimann, H.; Nezu, J.; Friedel, W.; Loff, S.; Jeschke, R.; Müller, O.; Back, W.; Zimmer, M. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 38-43. [CrossRef]

- Yehia, L.; Heald, B.; Eng, C. Clinical Spectrum and Science Behind the Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 800-811. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.; de Castro, F.D.; Carvalho, P.B.; Moreira, M.J.; Rosa, B.; Cotter, J. PillCam(R) SB3 capsule: Does the increased frame rate eliminate the risk of missing lesions? World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 3066-3068. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.J.; Zanati, S.; Dubcenco, E.; Christodoulou, D.; Cirocco, M.; Kandel, G.; Kortan, P.; Haber, G.B.; Marcon, N.E. Capsule endoscopy regional transit abnormality: a sign of underlying small bowel pathology. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003, 58, 598-602. [CrossRef]

- Monkemuller, K.; Fry, L.C.; Ebert, M.; Bellutti, M.; Venerito, M.; Knippig, C.; Rickes, S.; Muschke, P.; Rocken, C.; Malfertheiner, P. Feasibility of double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted chromoendoscopy of the small bowel in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy 2007, 39, 52-57. [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Lefor, A.T.; Mutoh, H.; Yano, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Sunada, K.; Nishimura, N.; Miura, Y.; Sato, H.; Shinhata, H.; et al. Endoscopic ultrasound with double-balloon endoscopy in the evaluation of small-bowel disease. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28, 2428-2436. [CrossRef]

- Honda, W.; Ohmiya, N.; Hirooka, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Miyahara, R.; Ohno, E.; Kawashima, H.; Itoh, A.; Watanabe, O.; Ando, T.; Goto, H. Enteroscopic and radiologic diagnoses, treatment, and prognoses of small-bowel tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 76, 344-354. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, A.; Nakamura, M.; Watanabe, O.; Yamamura, T.; Funasaka, K.; Ohno, E.; Kawashima, H.; Miyahara, R.; Goto, H.; Hirooka, Y. Endoscopic Characteristics, Risk Grade, and Prognostic Prediction in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors of the Small Bowel. Digestion 2017, 95, 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alcalá, A.; Fry, L.C.; Kröner, T.; Peter, S.; Contreras, C.; Mönkemüller, K. Endoscopic spectrum and practical classification of small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) detected during double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy international open 2021, 9, E507-e512. [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2013, 42, 399-415. [CrossRef]

- Magome, S.; Sakamoto, H.; Shinozaki, S.; Okada, M.; Yano, T.; Sunada, K.; Lefor, A.K.; Yamamoto, H. Double-Balloon Endoscopy-Assisted Balloon Dilation of Strictures Secondary to Small-Intestinal Lymphoma. Clinical endoscopy 2020, 53, 101-105. [CrossRef]

- Yantiss, R.K.; Odze, R.D.; Farraye, F.A.; Rosenberg, A.E. Solitary versus multiple carcinoid tumors of the ileum: a clinical and pathologic review of 68 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2003, 27, 811-817. [CrossRef]

- Manguso, N.; Gangi, A.; Johnson, J.; Harit, A.; Nissen, N.; Jamil, L.; Lo, S.; Wachsman, A.; Hendifar, A.; Amersi, F. The role of pre-operative imaging and double balloon enteroscopy in the surgical management of small bowel neuroendocrine tumors: Is it necessary? J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 207-212. [CrossRef]

- Latchford, A.R.; Clark, S.K. Gastrointestinal aspects of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2022, 58-59, 101789. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Hyer, W. Practical management of polyposis syndromes. Frontline gastroenterology 2019, 10, 379-387. [CrossRef]

- Pennazio, M.; Rondonotti, E.; Despott, E.J.; Dray, X.; Keuchel, M.; Moreels, T.; Sanders, D.S.; Spada, C.; Carretero, C.; Cortegoso Valdivia, P.; et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 58-95. [CrossRef]

- Ohmiya, N.; Taguchi, A.; Shirai, K.; Mabuchi, N.; Arakawa, D.; Kanazawa, H.; Ozeki, M.; Yamada, M.; Nakamura, M.; Itoh, A.; et al. Endoscopic resection of Peutz-Jeghers polyps throughout the small intestine at double-balloon enteroscopy without laparotomy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 61, 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Yano, T.; Miyata, T.; Nishimura, N.; Shinhata, H.; Sato, H.; Sunada, K.; Sugano, K. Nonsurgical management of small-bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with extensive polypectomy by using double-balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 74, 328-333. [CrossRef]

- Takakura, K.; Kato, T.; Arihiro, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Arai, Y.; Nakao, Y.; Komoike, N.; Itagaki, M.; Odagi, I.; Hirohama, K.; et al. Selective ligation using a detachable snare for small-intestinal polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Endoscopy 2011, 43 Suppl 2 UCTN, E264-265. [CrossRef]

- Yano, T.; Shinozaki, S.; Yamamoto, H. Crossed-clip strangulation for the management of small intestinal polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Dig Endosc 2018, 30, 677. [CrossRef]

- Khurelbaatar, T.; Sakamoto, H.; Yano, T.; Sagara, Y.; Dashnyam, U.; Shinozaki, S.; Sunada, K.; Lefor, A.K.; Yamamoto, H. Endoscopic ischemic polypectomy for small-bowel polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 744-748. [CrossRef]

- Limpias Kamiya, K.J.L.; Hosoe, N.; Takabayashi, K.; Okuzawa, A.; Sakurai, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Miyanaga, R.; Sujino, T.; Ogata, H.; Kanai, T. Feasibility and Safety of Endoscopic Ischemic Polypectomy and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (with Video). Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 252-258. [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Sunada, K.; Yano, T.; Arashiro, M.; Miyata, T.; Sugano, K. Reduction of ileoileal intussusception by using double-balloon endoscopy in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 72, 658-659. [CrossRef]

- Oguro, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Yano, T.; Funayama, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Nagayama, M.; Sunada, K.; Lefor, A.K.; Yamamoto, H. Endoscopic treatment of intussusception due to small intestine polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Endoscopy international open 2022, 10, E1583-E1588. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E.J. Follow-up study of a family group exhibiting dominant inheritance for a syndrome including intestinal polyps, osteomas, fibromas and epidermal cysts. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1962, 14, 376-390.

- Saurin, J.C.; Ligneau, B.; Ponchon, T.; Leprêtre, J.; Chavaillon, A.; Napoléon, B.; Chayvialle, J.A. The influence of mutation site and age on the severity of duodenal polyposis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 55, 342-347. [CrossRef]

- Iwama, T.; Tamura, K.; Morita, T.; Hirai, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Koizumi, K.; Shirouzu, K.; Sugihara, K.; Yamamura, T.; Muto, T.; Utsunomiya, J. A clinical overview of familial adenomatous polyposis derived from the database of the Polyposis Registry of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol 2004, 9, 308-316. [CrossRef]

- Jagelman, D.G.; DeCosse, J.J.; Bussey, H.J. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet 1988, 1, 1149-1151. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gurudu, S.R.; Koptiuch, C.; Agrawal, D.; Buxbaum, J.L.; Abbas Fehmi, S.M.; Fishman, D.S.; Khashab, M.A.; Jamil, L.H.; Jue, T.L.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in familial adenomatous polyposis syndromes. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 963-982 e962. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Ishikawa, H.; Ezoe, Y.; Arao, M.; Suzuki, S.; Iwatsubo, T.; Kato, M.; Tonai, Y.; Shichijo, S.; et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective exploratory study. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 511-517. [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Yano, T.; Miyahara, S.; Nagayama, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shinozaki, S.; Sunada, K.; Lefor, A.K.; Yamamoto, H. Double-balloon endoscopy facilitates efficient endoscopic resection of duodenal and jejunal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 517-521. [CrossRef]

- Binmoeller, K.F.; Shah, J.N.; Bhat, Y.M.; Kane, S.D. "Underwater" EMR of sporadic laterally spreading nonampullary duodenal adenomas (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 78, 496-502. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, Y.; Uedo, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Higashino, K.; Hanaoka, N.; Akasaka, T.; Kato, M.; Hamada, K.; Tonai, Y.; Matsuura, N.; et al. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 154-158. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Hamada, K.; Nakahira, H.; Shimamoto, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Tani, Y.; Shichijo, S.; Maekawa, A.; Kanesaka, T.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of intensive downstaging polypectomy (IDP) for multiple duodenal adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 515-523. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).