Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

05 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Maternal Morbidities

3.2. Infant Infections

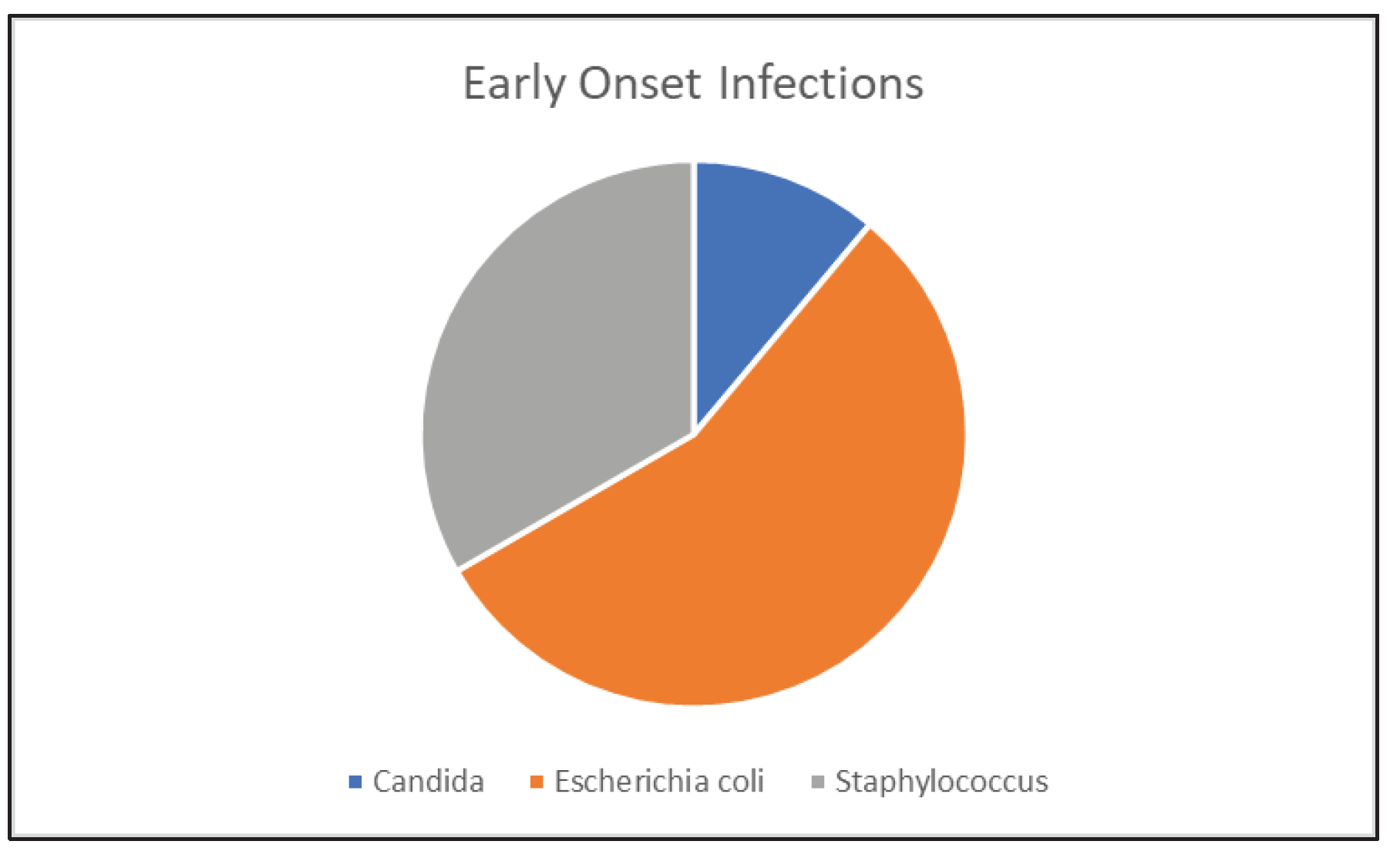

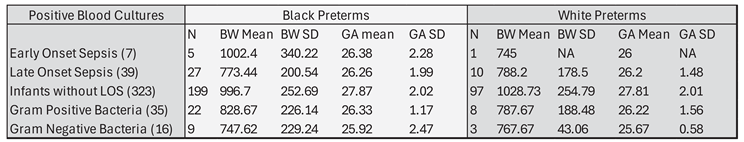

3.1.1. Early Onset Sepsis

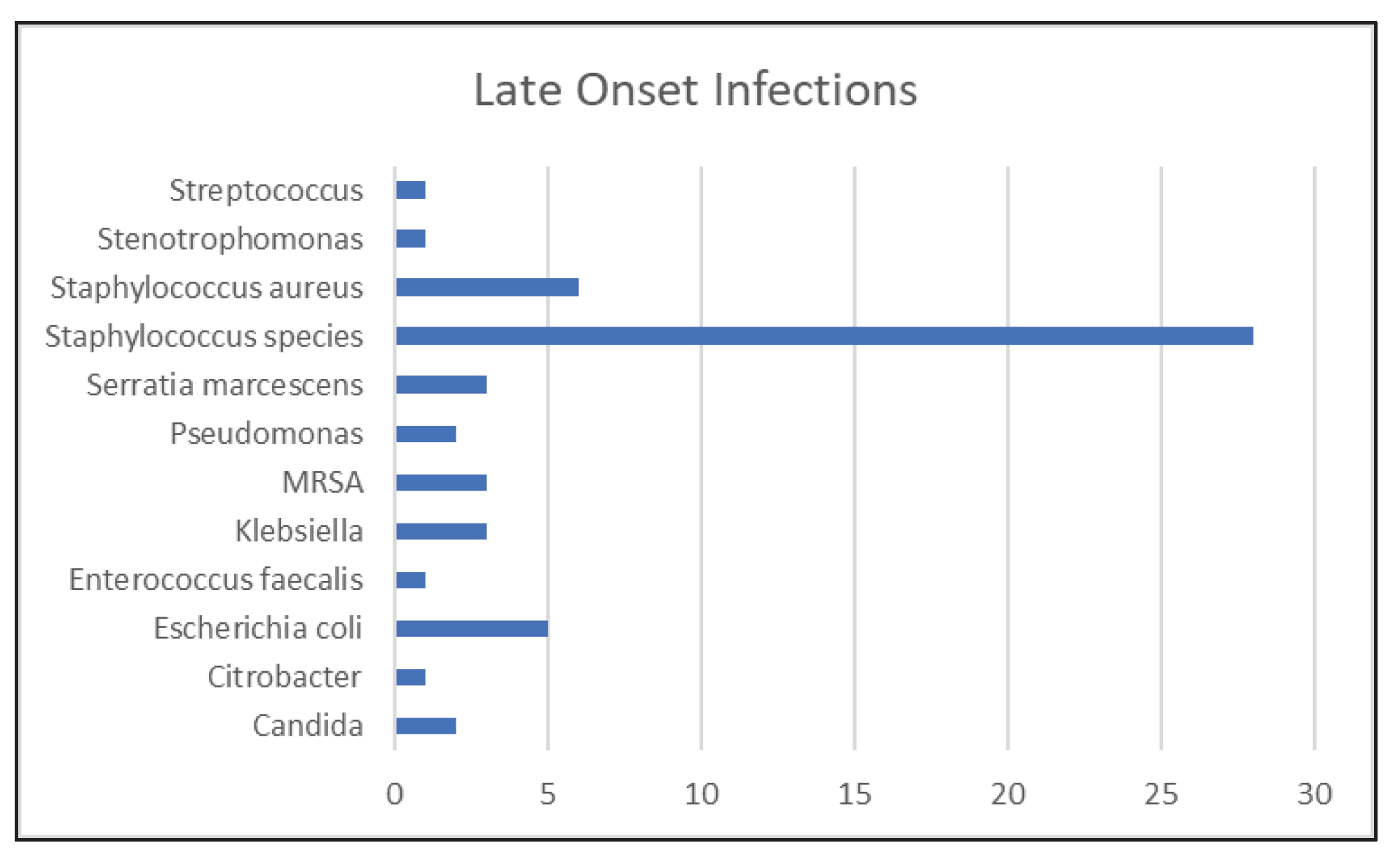

3.1.2. Late Onset Sepsis

3.1.3. Urinary Tract Infections

3.1.4. Respiratory Tract Infections

3.1.5. Cerebral Spinal Fluid Infections

3.1.6. Necrotizing Enterocolitis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MHS, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ, Statistics DoV. Births: Final Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2015, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, OM. Exploring the decline in the singleton preterm birth rate in the United States, 2019–2020. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Statistics NCfH; 2022 2022.

- Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant Mortality Statistics From the 2013 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. National vital statistics reports. 2015, 64, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fanaroff A, Hack M, Walsh M. The NICHD neonatal reseach network: changes in practic adn outcomes during the first 15 years. Seminars in Neonatology. 2003, 27, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertugrul S, Aktar F, Yolbas I, Yilmaz A, Elbey B, Yildirim A, et al. Risk Factors for Health Care-Associated Bloodstream Infections in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Iran J Pediatr. 2016, 26, e5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek Eken M, Tuten A, Ozkaya E, Karatekin G, Karateke A. Major determinants of survival and length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit of newborns from women with premature preterm rupture of membranes. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2017, 30, 1972–1975. [Google Scholar]

- Janevic T, Zeitlin J, Auger N, Egorova NN, Hebert P, Balbierz A, et al. Association of Race/Ethnicity With Very Preterm Neonatal Morbidities. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018, 172, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Social Epidemiology of Perceived Discrimination in the United States: Role of Race, Educational Attainment, and Income. Int J Epidemiol Res. 2020, 7, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millender E, Barile JP, J RB, Harris RM, De Faria L, Wong FY, et al. Associations between social determinants of health, perceived discrimination, and body mass index on symptoms of depression among young African American mothers. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021, 35, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers CP, Carlo WA, McDonald SA, Das A, Ambalavanan N, Bell EF, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities Among Extremely Preterm Infants in the United States From 2002 to 2016. JAMA network open. 2020, 3, e206757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature B, Assuring Healthy O. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Behrman RE, Butler AS, editors. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2007, National Academy of Sciences.; 2007.

- Xu X, Grigorescu V, Siefert KA, Lori JR, Ransom SB. Cost of racial disparity in preterm birth: evidence from Michigan. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009, 20, 729–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh F, Douglas W, Catenacci V, Machon C, Fox-Robichaud AE. Social Determinants of Health Associated With the Development of Sepsis in Adults: A Scoping Review. Crit Care Explor. 2022, 4, e0731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg RG, Kandefer S, Do BT, Smith PB, Stoll BJ, Bell EF, et al. Late-onset Sepsis in Extremely Premature Infants: 2000-2011. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2017, 36, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen R, Romain O, Tauzin M, Gras-Leguen C, Raymond J, Butin M. Neonatal bacterial infections: Diagnosis, bacterial epidemiology and antibiotic treatment. Infect Dis Now. 2023, 53, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll BJ, Puopolo KM, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, Bell EF, Carlo WA, et al. Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis 2015 to 2017, the Rise of Escherichia coli, and the Need for Novel Prevention Strategies. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e200593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey AC, Hossain MI, Afroze S, Dey SK, Mannan MA, Shahidullah M. A Survey on Current Practice of Management of Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Mymensingh Med J. 2016, 25, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Han W, Su Y, Wang N, Chen X, Ma J, et al. Perinatal risk factors for neonatal early-onset sepsis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2023, 36, 2259049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghossian NS, Page GP, Bell EF, Stoll BJ, Murray JC, Cotten CM, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight infants from singleton and multiple-gestation births. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013, 162, 1120–1124.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köstlin-Gille N, Härtel C, Haug C, Göpel W, Zemlin M, Müller A, et al. Epidemiology of Early and Late Onset Neonatal Sepsis in Very Low Birthweight Infants: Data From the German Neonatal Network. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2021, 40, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Speer CP. Late-onset neonatal sepsis: recent developments. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2015, 100, F257–F263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins SA, Glaser K. Updates in Late-Onset Sepsis: Risk Assessment, Therapy, and Outcomes. Neoreviews. 2022, 23, 738–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dail RB, Everhart KC, Hardin JW, Chang W, Kuehn D, Iskersky V, et al. Predicting Infection in Very Preterm Infants: A Study Protocol. Nursing research. 2021, 70, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nist MD, Casavant SG, Dail RB, Everhart KC, Sealschott S, Cong XS. Conducting Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Research During a Pandemic: Challenges and Lessons Learned. Nursing research. 2022, 71, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick R, Boutzoukas AE, Chan E, Girgis V, Kinduelo V, Kwabia SA, et al. Urinary Tract Infection Epidemiology in NICUs in the United States. American journal of perinatology. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbar JD, Greenberg LT, Buzas JS, Ehret DEY, Soll RF, Edwards EM. Trends in Mortality and Morbidities for Infants Born 24 to 28 Weeks in the US: 1997-2021. Pediatrics. 2024, 153, e2023064153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham N, Fazio T, Johnson D, Skandarajah A, Hayes IP. Hospital Acquired Infections in Surgical Patients: Impact of COVID-19-Related Infection Prevention Measures. World Journal of Surgery. 2022, 46, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar U, Awaisu A, Khan AH, Alam K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare-Associated Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghossian NS, Geraci M, Lorch SA, Phibbs CS, Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Racial and Ethnic Differences Over Time in Outcomes of Infants Born Less Than 30 Weeks' Gestation. Pediatrics. 2019, 144, e20191106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuck, TA. Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. Seminars in perinatology. 2017, 41, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman P, Dominguez TP, Burke W, Dolan SM, Stevenson DK, Jackson FM, et al. Explaining the Black-White Disparity in Preterm Birth: A Consensus Statement From a Multi-Disciplinary Scientific Work Group Convened by the March of Dimes. Front Reprod Health. 2021, 3, 684207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Jiang T, Zhang W, Li C, Chen J, Xiang D, et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: 4 years of collection. Am J Infect Control. 2017, 45, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock A, Hanson BM, Ruffin F, Parsons JB, Park LP, Sharma-Kuinkel B, et al. Clinical and Molecular Analyses of Recurrent Gram-Negative Bloodstream Infections. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2023, 76, e1285–e1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath CL, Bettinger B, Stimpson M, Bell SL, Coker TR, Kronman MP, et al. Identifying and Mitigating Disparities in Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in Minoritized Racial, Ethnic, and Language Groups. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu M, Wang L, Zhuge Z, Li W, Zheng Y, Mai J, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Multi-Drug Resistance in Neonatal Sepsis Caused by Escherichia coli. Infect Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaure C, Geslain G, Birgy A, Bidet P, Poilane I, Allain M, et al. Early-Onset Infection Caused by Escherichia coli Sequence Type 1193 in Late Preterm and Full-Term Neonates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024, 30, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan JM, Nugent C, Wilson A, Verlander NQ, Alexander E, Fleming P, et al. Clinical outcomes of Staphylococcus capitis isolation from neonates, England, 2015-2021: a retrospective case-control study. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2023.

- Chavignon M, Coignet L, Bonhomme M, Bergot M, Tristan A, Verhoeven P, et al. Environmental Persistence of Staphylococcus capitis NRCS-A in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Role of Biofilm Formation, Desiccation, and Disinfectant Tolerance. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e0421522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [A multicenter prospective cohort study of late-onset sepsis and its poor prognosis in very low birth weight infants]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2023, 61, 228–234. [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiec D, Słaba M, Torzewska A. Substances Secreted by Lactobacillus spp. from the Urinary Tract Microbiota Play a Protective Role against Proteus mirabilis Infections and Their Complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 25, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobec K, Mukenauer R, Keše D, Erčulj V, Grosek Š, Perme T. Association between colonization of the respiratory tract with Ureaplasma species and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in newborns with extremely low gestational age: a retrospective study. Croat Med J. 2023, 64, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanishi Y, Hirata K, Nozaki M, Mochizuki N, Hirano S, Wada K. The Association between Early Gram-Negative Bacteria in Tracheal Aspirate Cultures and Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia among Extremely Preterm Infants Requiring Prolonged Ventilation. American journal of perinatology. 2023, 40, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt B, Rogers C, Blais RM, Adachi K, Sathyavagiswaran L. Paenibacillus Sepsis and Meningitis in a Premature Infant: A Case Report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2021, 42, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeon SD, Welliver RC, Sr. Paenibacillus alvei Sepsis in a Neonate. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2016, 35, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu X, Liang H, Li F, Zhang R, Zhu Y, Zhu X, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: current understanding of the prevention and management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024, 40, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuna A, Sampath V, Khashu M. Racial Disparities in Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Front Pediatr. 2021, 9, 633088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree IM, Smits-Wintjens VE, Rijntjes-Jacobs EG, Pelsma IC, Steggerda SJ, Walther FJ, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in small-for-gestational-age neonates: a matched case-control study. Neonatology. 2014, 105, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).