1. Introduction

An important reaction involving nitric oxide (•NO) within living cells is its interaction with iron and specific biological ligands, including proteins, peptides, and amino acids [

1,

2]. The interaction results in the formation of dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNICs) characterized by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)-detectable g

┴ = 2.04 and g

║ = 2.014 signals ( the so-called 2.03 signals, in accordance with the average value of its g-factor [

1]). DNICs formation was observed in cells and tissues exposed to endogenous [

3] or exogenous •NO [

4]. The nature of biological ligands forming DNICs and their interactions are not well understood. EPR analysis of frozen solutions revealed that the anisotropy of g values of formed DNICs displays significant variations depending on geometry, electronic structure and molecular weight of involved ligands, and is an important indicator of ligand type and the complex structure. Nitrite and •NO can react with heme and non-heme iron proteins to form DNICs, however, kinetics of in vivo formation and distinctions between DNICs derived from nitrite or •NO remains unclear [

5]. During formation of DNICs a chelatable iron might be also sequestered, resulting in an iron-starved phenotype. Thus, DNICs formation affects cellular iron homeostasis and alters activity of iron-containing proteins, but also reduces the pro-oxidant capacity of cells [

3].

DNICs formation may involve a variety of iron-containing proteins, such as those comprising iron-sulfur centers [

6,

7,

8], heme groups [

9] or non-heme iron [

8,

10,

11]. Some examples of proteins that have been shown to form DNIC include mitochondrial aconitase [

12,

13,

14,

15], ribonucleotide reductase [

16], cytochrome c oxidase [

17] and nitrogenase [

18]. However, the specific proteins that are targeted during DNIC formation can vary depending on the cell type and physiological context [

5]. Biosynthesis of DNICs was first discovered in 1964 [

19], and continued investigations revealed tetrahedral [(NO)

2Fe(L)

2] complex, as a natural and ubiquitous DNIC formed from interaction of

•NO with non-heme iron-sulphur ([Fe-S]) proteins and cellular labile iron pool [

8,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

DNICs involvement in various

•NO-mediated cellular and organismal functions has been described in several reviews [

8,

35]. There is an increasing awareness of the biological role of DNICs, and this warrants further studies on DNICs structure and on the pre-requirements for their biosynthesis. DNICs have been proposed as a "working form" of

•NO under physiological conditions [

19]. On the other hand, high-molecular-weight DNICs (HMWDNICs) accumulate in lipoprotein aggregates that contain partially hydrophobic fragments, such as lipid bilayers. These complexes are highly stable and inert, as demonstrated by their resistance to decomposition in the presence of iron chelators [

36]. HMWDNICs seem to be the most abundant form of DNICs observed in vivo, however this might be biased by the fact that their enhanced stability may contribute to their higher abundance and better detectability in cellular extracts after protein fractionation [

37].

The objective of this study was to investigate the contribution of low- (LMW) and high-molecular-weight (HMW) ligands in formation of DNICs. Our previous study revealed that DNICs are formed primarily in the endosomal/lysosomal fraction and degradation of iron-containing metaloproteins is crucial for its formation in vivo [

38]. This prompted us to undertake a more detailed investigation on the role of protein degradation in DNICs formation, through the use of proteolysis inhibitors of different specificity.

In this study, K562 human erythroid precursor cells were treated with proteolysis inhibitors followed by treatment with a •NO donor and DNICs specific signal was recorded with regard to its shape and intensity. In addition, as glutathione appears to be the most abundant low molecular weight thiol ligand, its role in DNICs formation was also investigated.

The function of low molecular weight DNICs (LMWDNICs) as

•NO donors has been observed: administration of LMWDNICs to experimental animals resulted in the formation of high molecular weight protein-bound DNICs (HMWDNICs) due to transfer of Fe(NO)

2 groups from added complexes to proteins [

39,

40].

2. Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise indicated all chemicals were purchased in Sigma-Aldrich (Merck), Poland.

Cell lines and chemicals

K562 human erythroid precursor cells (ATCC CCL-243) were grown in suspension in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics in humidified 5% CO2 incubator to a final density of 107 cells per milliliter. One batch of K562 cells was stably transfected with transferrin heavy chain (FERH) sequence containing DNA plasmid by electroporation using the BTX ECM600 apparatus, according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The efficiency of transfection was evaluated using green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding plasmids (4.7 kbp; p-EGFP-N1) co transfected with FERH vector. The transfected cell lines were designated K562/FERH.

Inhibition of proteolysis

The cells were treated with the following inhibitors: 15 mM of ammonium chloride (lysosome inhibitor; Sigma Aldrich - Germany), 100 μg/mL of leupeptin (lysosome inhibitor; Sigma), 50 μM ALLM (N-acetyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-methioninal; lysosome inhibitor; Sigma - Germany), 20 μM lactacystin (proteasome inhibitor; Sigma - Germany), 25 μM MG-132 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al; proteasome inhibitor, Sigma - Germany), 50 μM MG-101 (ALLN, N-acetyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-norleucinal, a calpain and cathepsin inhibitor; Sigma - Germany) or 5 μM MG-262 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-B(OH)2; proteasome inhibitor; BioMol - Germany). NO donor was added to generate DNICs.

Generation of DNICs

After 2, 4 or 6 hours of treatment with proteolysis inhibitor in the complete medium at 37°C, the cells were treated with •NO donor (diethylammonium (Z)-1-(N,N-diethylamino)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate, DEANO) for 15 min at 37 °C, at concentration 70μM. The final •NO concentration in the culture medium was 100 μM). The donor spontaneously dissociates in a pH dependent, first-order process with a half-life of 2 min at 37°C, pH 7.4. Untreated cells served as a reference.

EPR measurements

DNICs formation was monitored by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). Samples were prepared according to the following procedure: NO-treated cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 250 x g, resuspended in 200 µL of PBS buffer and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. EPR spectra were measured on an X-band Bruker 300e spectrometer. All spectra were recorded at 77 K with microwave power of 1 mW and modulation amplitude of 3 G, time constant 41 ms. The characteristic EPR signals corresponding to DNICs formation were obtained. Once the EPR signal intensity had been measured, the protein concentration in each sample was assayed by the Bradford method [

41].

Preparation of subcellular fractions

To investigate the role of ligands in DNICs formation in various cellular compartments, cell homogenates were treated with DEANO and fractionated by differential centrifugation. Approximately 108 cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and pelleted at 300 x g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in the ice-cold buffer A (250mM sucrose; 1mM EDTA; 20mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N’-ethanesulfonic acid) and broken in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged through the Centricon centrifugal filter devices (Amicon) with cut-off values: 100000 MWCO (molecular weight of ligands < 100 kDa) and 30000 MWCO (molecular weight of ligands <30 kDa) at 1,000 x g for 10 min. EPR spectra were recorded for each fraction separately and recalculated for protein content.

Glutathione and thiol determination

A total content of compounds containing thiol groups was measured fluorometrically with the use of monobromobimane (MBB, Sigma Aldrich), a non-fluorescent bimane dye that adds a fluorescent tag when reacting with thiol groups (Ex/Em of thiol conjugate = 380/475 nm). The cellular GSH content was also measured fluorometrically, but with the use of monochlorobimane (MCB, Sigma Aldrich), a bimane dye, specific for glutathione even in the presence of other thiol groups (Ex/Em of glutathione conjugate = 380/460 nm) [

42].

In some experiments, to lower the cellular glutathione content, approx. 25 x 106 of cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in in 25 mL complete medium containing 200 μM D,L-buthionine [S,R]-sulfoximine (BSO), a γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase inhibitor. In yet another series of experiments, to increase the cellular glutathione content the cells were incubated with 10 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a glutathione synthesis precursor, in the same conditions. After incubation, DEANO was added to generate DNIC, and EPR signal was recoded and recalculated for protein content measured by the Bradford method.

Statistical evaluation

The significance of differences between the mean values was analyzed by a pairwise comparison using Student’s t-test for independent samples.

3. Results and discussion

Cellular proteins that might serve as a HMW-ligands, are degraded either in lysosomes, cytoplasmic organelles containing various types of proteases active at acidic pH, or targeted for degradation to proteasomes in a ubiquitin-dependent process, both processes easy to control using appropriate inhibitors. On the other hand, a level of the main potential LMW peptide ligand, glutathione, can be also controlled by the use of a specific precursor (NAC) or inhibitor (BSO) of its synthesis. In other words, the use of specific proteolysis inhibitors allows for elucidation of the role of HMW-ligands, whereas controlling the glutathione level allows for elucidation of the role of LMW-ligands in DNICs formation. The study also aimed to understand the relationship between both types of protein ligands in DNICs formation in various cellular compartments.

To further elucidate the role of HMW-ligands in intracellular DNIC formation, their cellular content was increased by the use of ferritin-overexpressing cells. Ferritin, is an iron storage protein known to promote DNICs formation [

43]. Thus, we aimed to explore how overabundance of HMW protein, such as ferritin, may affect the formation and stability of DNICs.

The effect of proteasome inhibitors on DNICs synthesis

To examine the effect of proteasomal proteolysis on DNIC formation, we inhibited proteasome with 20 µM lactacystin (LAC) [

49] or 25 µM MG-132 [

44,

50]. LAC covalently binds the active site N-terminal threonine residue of proteasome β-subunit to form an intermediate species, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone. Consequently, it inhibits proteasome-dependent proteolysis at concentrations of 20 μM or higher [

49]. MG-132 is a specific, potent, reversible and cell-permeable proteasome inhibitor that reduces degradation of ubiquitin-conjugated proteins by the 26S complex without affecting its ATPase and isopeptidase activities [

51,

52,

53]. This substrate-mimicking peptide acts primarily on the chymotrypsin-like site in the β subunit of proteasome. Both inhibitors strongly inhibited formation of DNIC in DEANO-treated K562 cells. Extremely low or no EPR signals were detected indicating that the treatment with proteasome inhibitors entirely stopped DNICs biosynthesis (

Figure 3). This result shows that proteins degraded in proteasomes are a very important source of DNICs components.

Effect of the total proteolysis inhibition on DNIC synthesis

Two inhibitors were applied that inhibit all types of cellular proteases, MG-101 and MG-262. MG-101 (N-acetyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-norleucinal; ALLN) is a cell-permeable inhibitor of calpain I, calpain II, cathepsin and cathepsin L. It inhibits neutral cysteine proteases and the proteasome [44, 50]. MG-262 is a highly potent and selective cell-permeable inhibitor of proteasome [

54] and probably lysosome proteolysis [

55]. MG-262, a boronic peptide acid, is a potent proteasome inhibitor that selectively and reversibly inhibits the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome [56, 57], while leupeptin inhibits serine, cysteine and threonine proteases but it does not inhibit α-chymotrypsin or thrombin. Leupeptin is a competitive transition state inhibitor and its inhibition may be relieved by an excess of substrate [58, 59]. The experiments revealed that total inhibition of the cellular proteolysis obtained with these inhibitors completely prevented DNICs formation. As both inhibitors gave identical results, only results for ALLN are shown (

Figure 3).

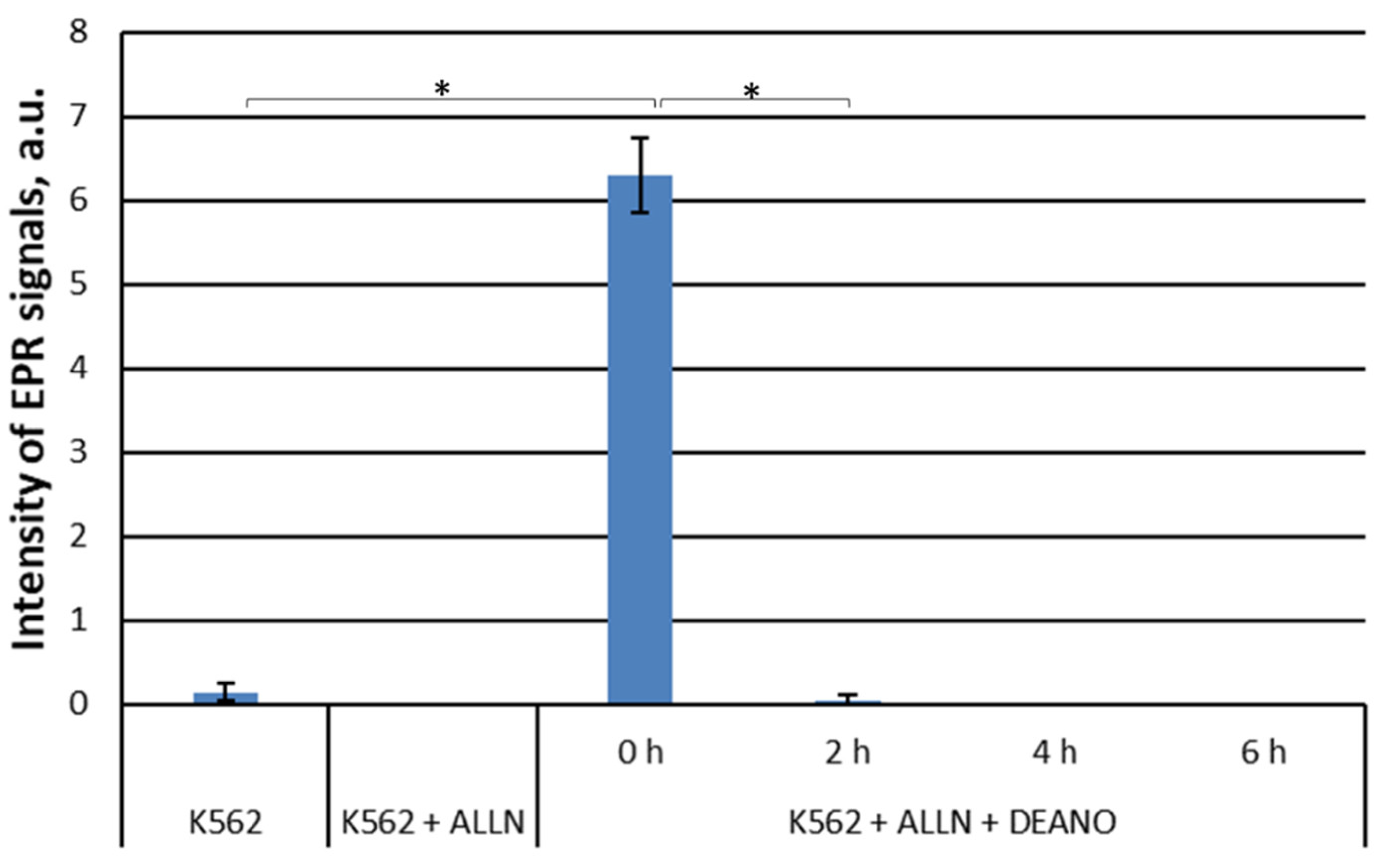

Figure 4.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 20µM ALLN for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 20µM ALLN for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

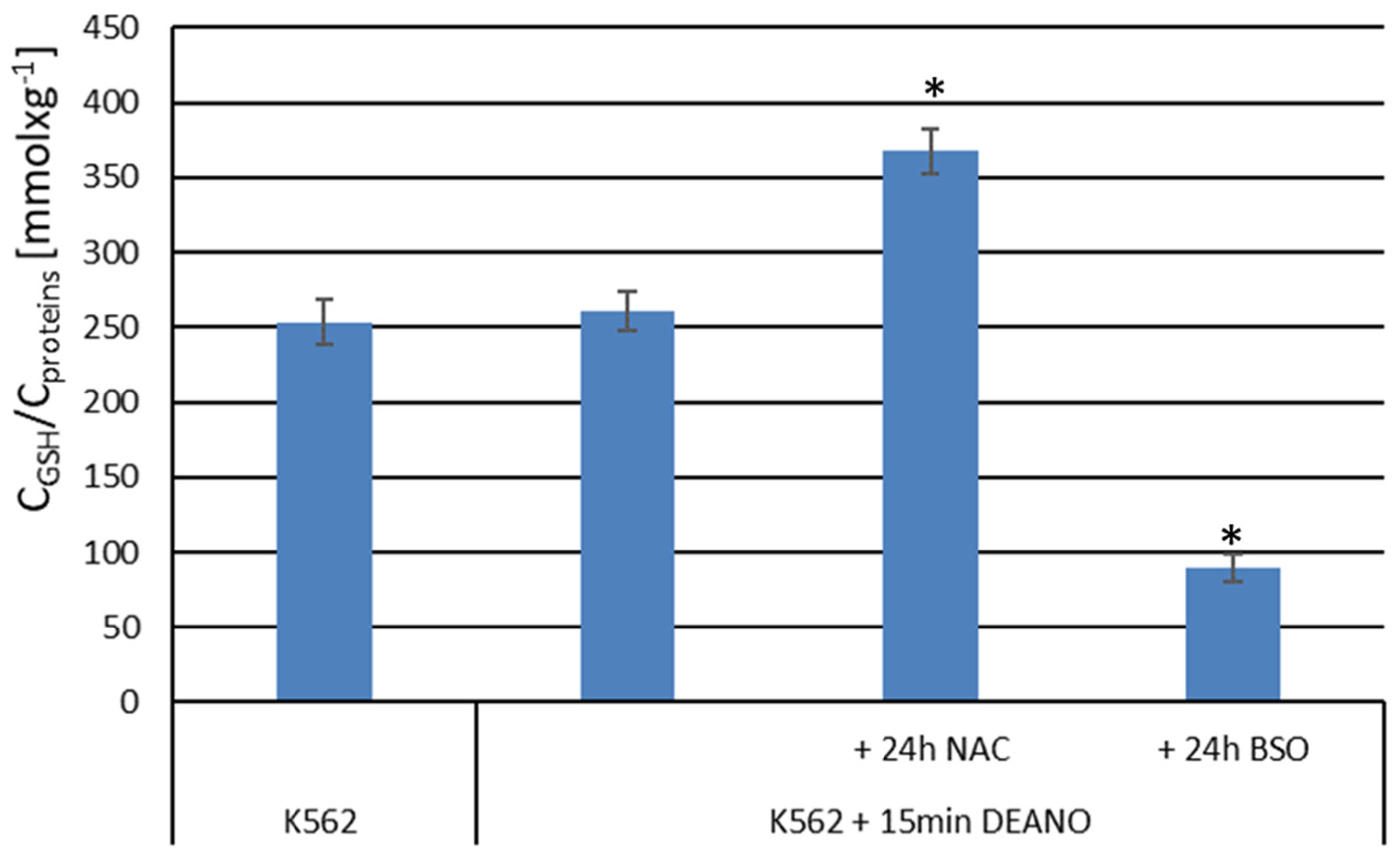

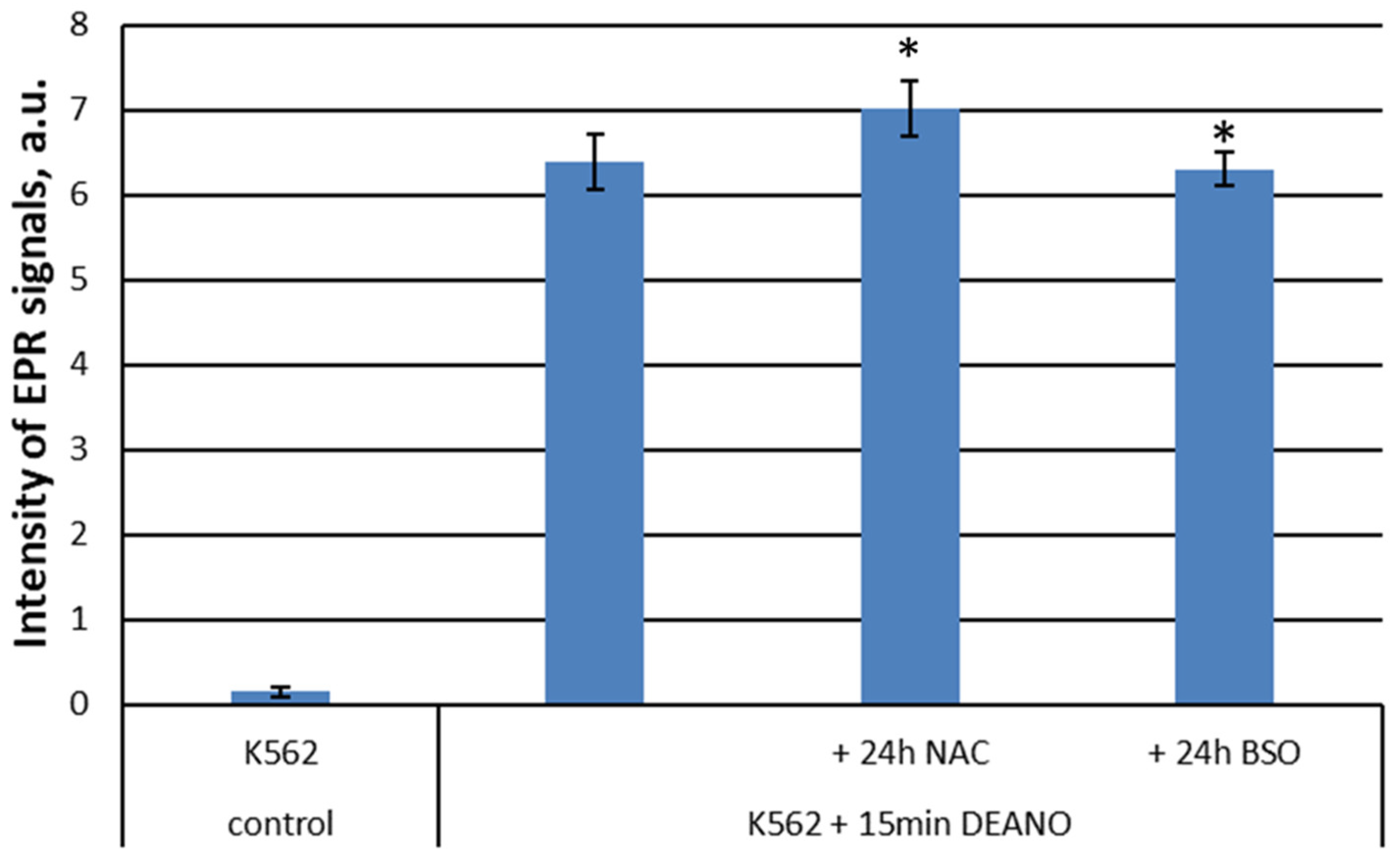

The effect of glutathione concentration modulation on DNICs synthesis

One of the aims of our studies was to evaluate the role of LMW thiol ligands in DNICs formation. Hence, the contribution of glutathione (GSH) in DNICs formation in K562 cells was evaluated. The cellular GSH content was modulated by treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which stimulates GSH synthesis by maintaining a high free cysteine pool, or by treatment with D,L-buthionine [S,R]-sulfoximine (BSO), a specific inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase, the first enzyme of glutathione synthesis pathway.

As shown in

Figure 5, treatment with DEANO did not affect cellular glutathione level. However, 24 h treatment with NAC stimulated glutathione synthesis and significantly increased its level roughly by 40%. In contrary, treatment with BSO, as expected, decreased the glutathione level, again roughly by 60%.

To examine the role of glutathione in DNICs formation, cell cultures pretreated with NAC or BSO were subsequently treated with DEANO, and intensity of EPR signal was compared with cells treated with DEANO alone. Despite big differences in glutathione level (

Figure 5), the intensity of EPR signal in DEANO-treated cells did not differ substantially neither in cells with increased glutathione level (NAC treated) nor in cells with decreased glutathione level (BSO treated), as compared with not treated cells. However, a statistically significant difference was revealed between NAC- and BSO-treated cells (

Figure 6). As the same cell cultures were used to obtain the data presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, these data suggest that glutathione had only a neglectable role in the formation of intracellular DNICs. Hence, we conclude that the inhibition of proteolysis is the decisive factor limiting the production of DNICs.

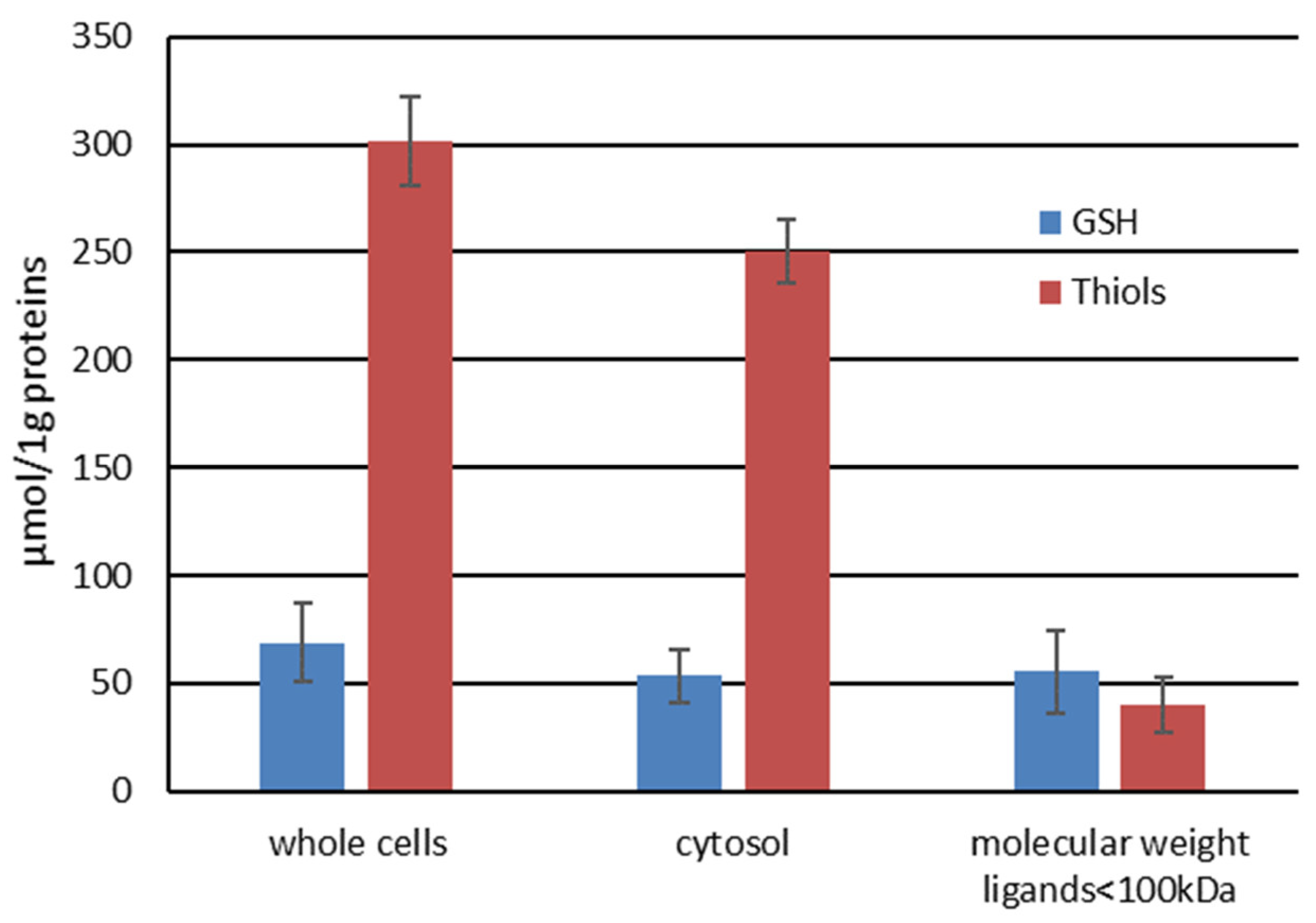

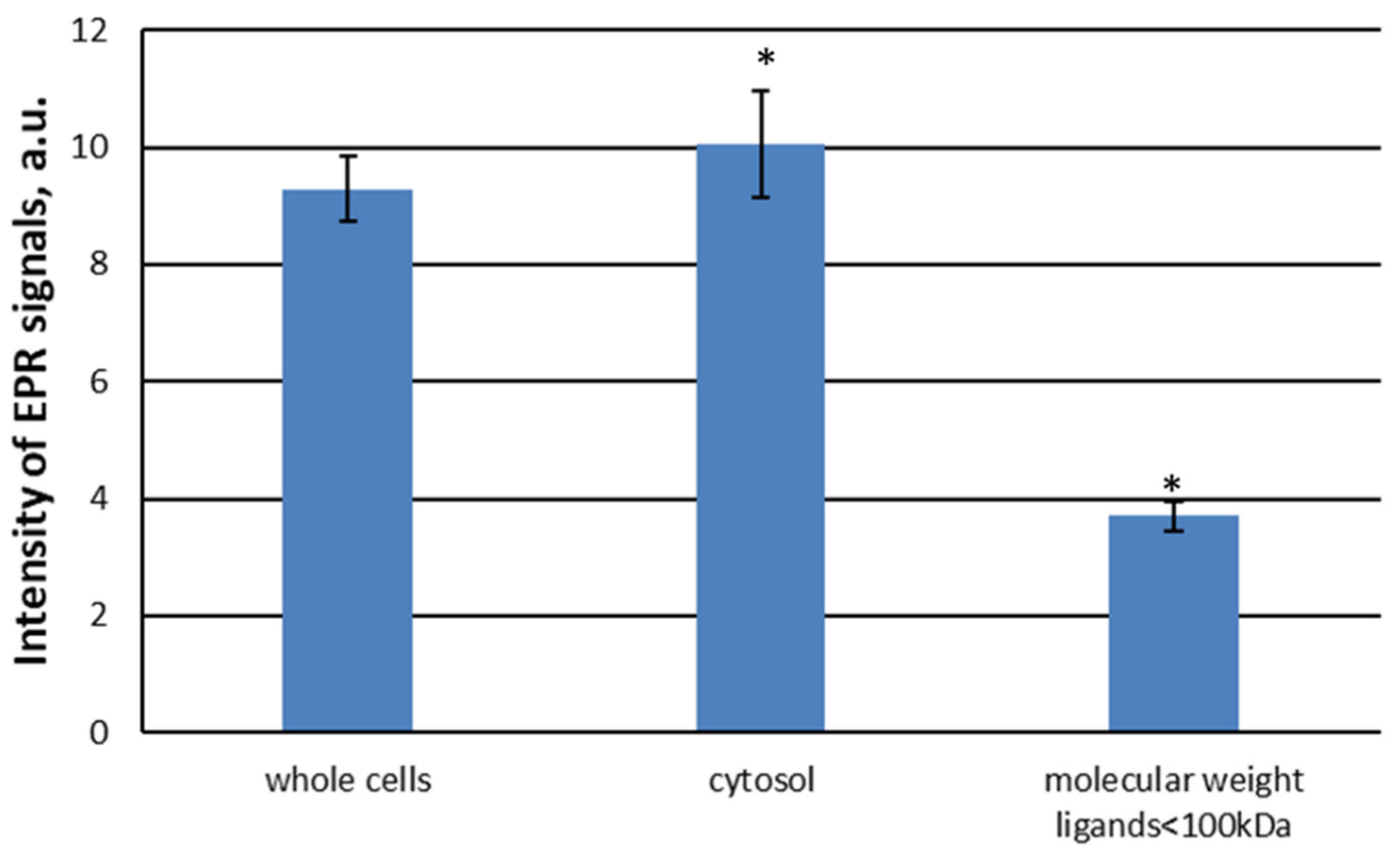

Cellular low and high molecular ligand fractions

The role of low and high molecular ligands in DNICs formation

in vivo was further examined by cell fractionation. K562 cell homogenate was treated with DEANO and fractionated. The high intensity EPR signal from DNICs was detected in the whole cell lysate and in the cytosol. The cytosol fraction was further fractionated by centrifugal filtration to obtain fraction with ligands < 100 kDa. As expected, centrifugation through the molecular membrane with a cut-off value of 100 kDa eliminated the majority of HMW thiols, with a neglectable effect on glutathione content (

Figure 7). With a molecular mass 0.3 kDa the same level of glutathione should be present in all fractions.

The intensity of EPR signal dramatically dropped when HMW proteins were filtered out (

Figure 8). The EPR signal intensity in <100 kDa fraction was less than 40% of this of unfiltered cytosol. All together these results further support the crucial role of HMW ligands in formation of DNICs.

Characterization of EPR signal of protein-bound DNICs

LMWDNICs, which are not bound to proteins, exhibit a symmetrical EPR signal at room temperature with a g-value of 2.03. Hyperfine Structure (HFS) analysis of the EPR signal of DNICs with cysteine showed that these complexes contain pairs of molecules of cysteine and NO (nitric oxide). The hyperfine structure (HFS) in the EPR signal at 273K is a result of the interaction between unpaired electron and nitrogen nuclei of NO ligands and protons of cysteine [

60]. The signal became narrower as the temperature increased, indicating that these DNICs are highly mobile at higher temperatures, leading to an averaging of the anisotropic properties of the signal [

60]. The anisotropic shape of the EPR signal at 273K of DNICs often encountered in biological systems suggests that these DNICs are bound to proteins [

60,

61,

62].

Prior investigations by Lee et al. [

63] laid the groundwork for understanding of EPR signal symmetry in ferritin-bound DNICs. An illustration of how the EPR signal at 77K is effected by specific ligands involved in the formation of protein bound DNICs was provided, demonstrating that the EPR signal of ferritin originated DNIC was a composite of signals from complexes bound either to histidine or cysteine residues of the protein. Notably, these two distinct species generated EPR signal that shared a common central value of approximately 2.03. However, they exhibited dissimilar symmetries, with the histidinyl complex displaying a rhombic symmetry, whereas the cysteinyl complex exhibited an axial symmetry [

27,

63,

64].

It's also worth noting that the symmetry of the EPR signal can also be influenced by the structural configuration of the protein ligands, as exemplified by the EPR spectra of DNICs associated with different isoforms of glutathione S-transferase [

65,

66]. Thus, DNICs bound to proteins with only one thiol group, such as bovine or human serum albumin, exhibit lower (rhombic) symmetry, resulting in an EPR signal with three different g-factor values. This decrease in symmetry suggests that DNICs incorporate a ligand, likely a histidine residue of the protein. When these protein-bound DNICs come into contact with an excess of LMW thiols (e.g. cysteine or glutathione), they undergo a reversible transformation, replacing the protein’s histidine ligand with the LMW thiol. This change in coordination results in a more axially symmetrical EPR signal. In cells and tissues, it's possible that DNICs can contain either two or one HMW protein ligand. In the latter case, the LMW ligand is incorporated into the DNIC that produce an EPR signal with an axially symmetrical tensor of the g-factor (g = 2.03) [

61].

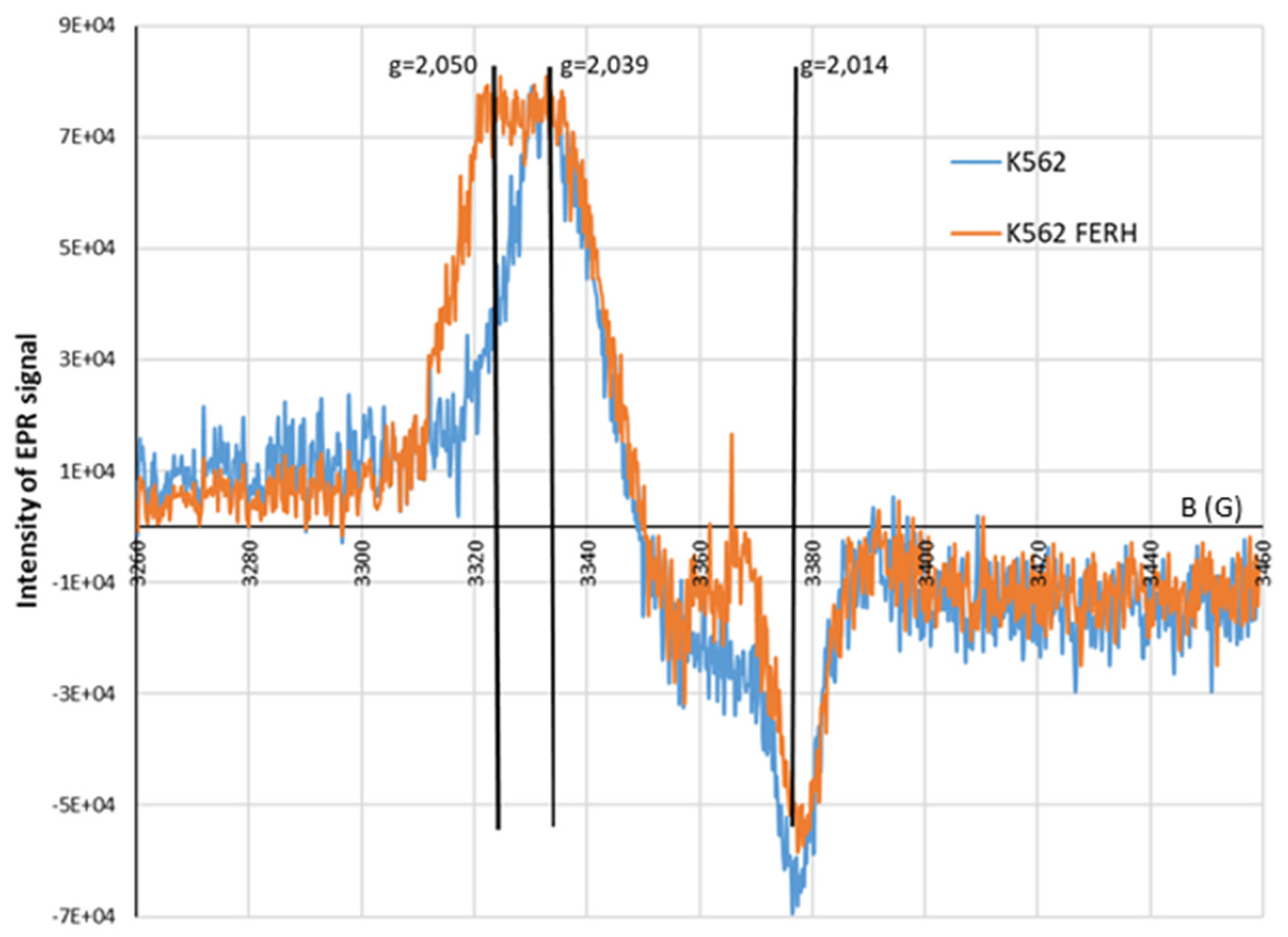

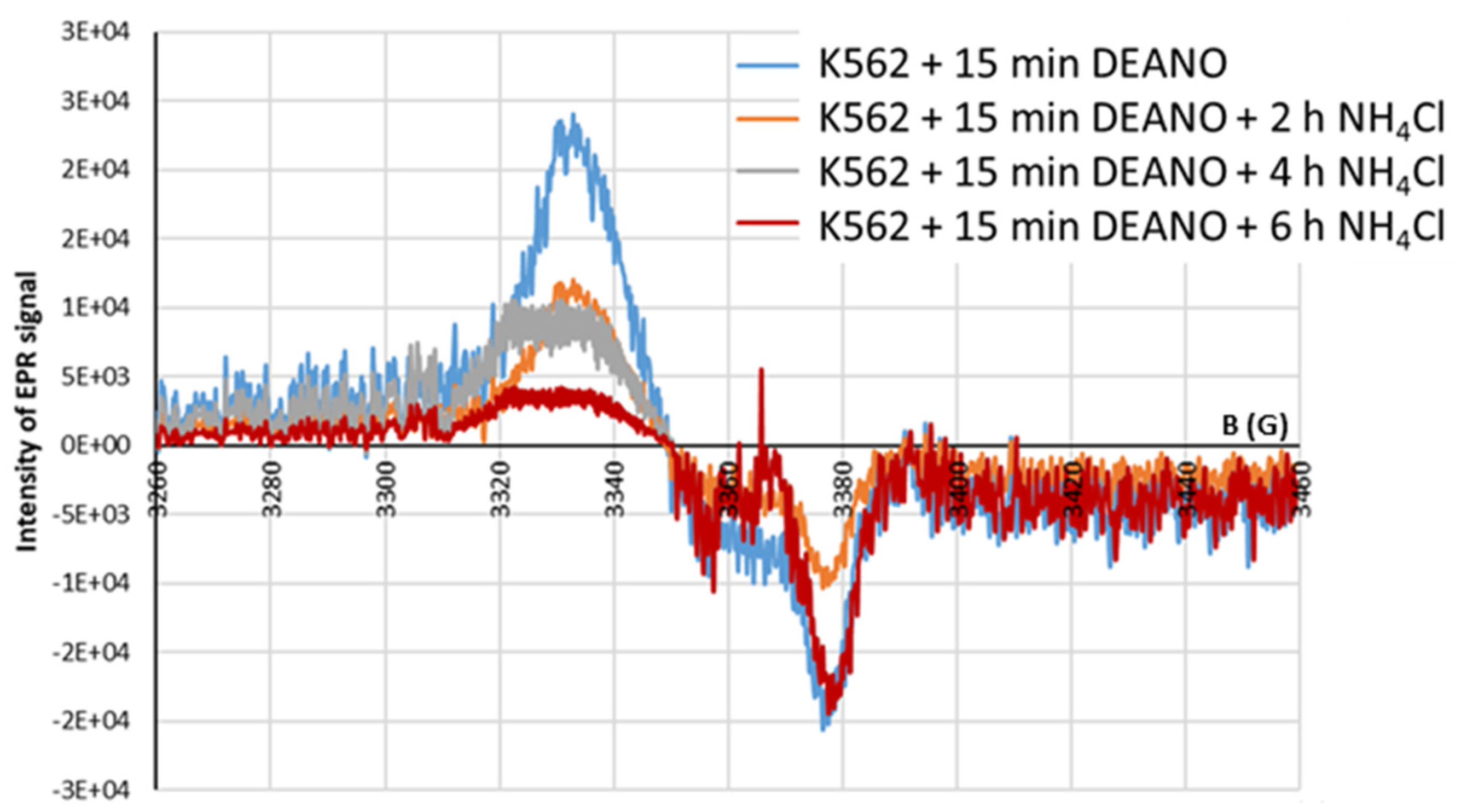

In this work, FERH overexpression (K562/FERH cells) was used as a strategy to promote the formation of larger and more stable HMWDNICs to investigate their distinctive properties and characteristics. The EPR signals recorded in wild-type K562 cells or K562/FERH cells differed substantially (

Figure 9). Comparison of spectra showed that at 77K the EPR signal of DNICs in K562/FERH cells showed a rhombic symmetry with g-factors 2.05, 2.03 and 2.014. This symmetry was lower than the one observed in the wild-type K562 cells, which signal showed the axial symmetry. Interestingly, the shape and g-factor symmetry of EPR signals of wild type K562 cells in which the physiological proteolysis was inhibited by NH

4CL treatment changed from axial to rhombic. The contribution of rhombic signal increased as inhibition progressed, while for untreated cells the axial signal predominated. After 4h incubation, the EPR signal showed rhombic symmetry with g-factors 2.05, 2.03 and 2.014. As stated in the literature, this type of spectral shape is associated with the presence in the complex of two different ligands: thiol and non-thiol descended from one molecule [

35,

67]. The rhombic g-tensor symmetry of DNIC EPR spectrum is observed for HMWDNICs with proteins. This might suggest that HMWDNICs were visible in the cells after incubation with NH

4Cl, while the LMWDNICs associated signal predominated in cells before proteolysis inhibition. We speculate that stability of HMWDNICs is higher than that of LMWDNICs, but formation of LMWDNICs is necessary for synthesis of HMWDNICs. This would explain decrease of signal intensity observed on

Figure 10 and the absence of DNICs formation in cells in which the inhibition of proteolysis was complete (see

Figure 3).

4. Conclusions

The study provides significant insights into the formation of DNICs in vivo and the role of different ligands in this process. Inhibition of lysosomal proteolysis by ammonium chloride led to a time-dependent decrease in DNICs formation, indicating that proteins degraded in lysosomes are an important source of DNIC components. This was confirmed by the use of two different inhibitors of protein degradation in lysosomes and cytosol, namely ALLM and leupeptin. The treatment resulted in even stronger inhibition of DNICs formation. In line, inhibition of protein degradation in proteasome by LAC almost entirely stopped DNICs biosynthesis. Finally, total proteolysis inhibition using ALLN or MG-262, which inhibit various proteases, prevented DNICs formation entirely. Altogether, the presented results underscore the critical importanceof protein degradation, both lysosomal and proteasomal in DNIC biosynthesis.

Furthermore, the study revealed only limited contribution of glutathione (GSH), a low molecular weight thiol, in DNICs biosynthesis. Modulation of GSH level only slightly affected DNICs formation, indicating a minor role of GSH in cellular DNIC formation. Cell fractionation demonstrated that DNIC signal was more intense in high-molecular-weight fractions of cytosol, further supporting the role of larger ligands, such as proteins, in DNICs stabilization.

The study revealed also a distinct EPR signal with rhombic symmetry in ferritin-overexpressing cells, suggesting the formation of more stable DNICs with large ferritin molecules, incorporating two different ligands in the coordination zone. In contrast, in wild-type K562 cells, EPR signal was of an axial symmetry implying more symmetrical environment around the unpaired electron, or more likely, a faster rotation of a paramagnetic species due to the lower molecular mass of ligands. It is proposed that stability of HMWDNICs is higher than that of LMWDNICs, however formation of LMWDNICs is necessary for the synthesis of HMWDNICs.

In summary, this research provides valuable insights into the role of lysosomal and proteasomal proteolysis, as well as the impact of GSH levels and molecular ligands in the synthesis of DNICs. The study sheds light on the distinct effects of different proteolytic inhibitors and highlights the importance of larger ligands, especially proteins, in DNICs formation. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for comprehending cellular redox regulation and metal-ion homeostasis. The findings may have implications for developing novel therapeutic approaches targeting metal-ion metabolism and for understanding redox signaling in various pathologies related to oxidative stress and altered metal-ion balance.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, K.E.W and M.K.; methodology, K.E.W., J.S. and H.L.; software, J.S.; validation, K.E.W., J.S., H.L. and M.K.; formal analysis, K.E.W., H.L. and M.K.; investigation, K.E.W., J.S., and H.L.; resources, M.K.; data curation, K.E.W., and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.E.W., and H.L.; reviewing and editing, K.E.W., J.S., H.L. and M.K.; visualization, K.E.W.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education grant No. N204077833

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Polish national law no ethical approval is necessary for studies not involving humans or animals. GMO works were approved by the Ministry of Environment (DLOPiKgmo-431-89/01-05/2006/06).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data arising from this study are available from corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

List of Abbreviations

| ALLM |

N-Acetyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-methioninal (lysosome inhibitor) |

| ATPases |

class of enzymes that catalyze hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate |

| BSO |

D,L-buthionine [S,R]-sulfoximine |

| DEANO |

2-(N,N- Diethyloamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide |

| DNICs |

dinitrosyl iron complexes |

| EDTA |

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EPR |

electron paramagnetic resonance |

| FERH |

heavy chain of ferritin |

| GSH |

glutathione |

| HMWDNICs |

dinitrosyl iron complexes with high-molecular-weight ligands |

| His |

histidine |

| HFS |

hyperfine structure |

| LMWDNICs |

dinitrosyl iron complexes with low-molecular-weight ligands |

| LAC |

lactacystin (proteasome inhibitor) |

| LEUPT |

leupeptin (lysosome inhibitor) |

| MG-101 |

N-Acetyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-norleucinal (calpain, lysosome and proteasome inhibitor) |

| MG-132 |

Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al (proteasome inhibitor) |

| MG-262 |

Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-B(OH)2 (calpain, lysosome and proteasome inhibitor) |

| NAC |

N-acetylcysteine |

| PBS |

phosphate-buffered saline |

References

-

Nitric Oxide in Transplant Rejection and Anti-Tumor Defense; Lukiewicz, S., Zweier, J.L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, 1998; ISBN 978-0-7923-8389-5.

- Ueno, T.; Yoshimura, T. The Physiological Activity and In Vivo Distribution of Dinitrosyl Dithiolato Iron Complex. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 82, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickok, J.R.; Sahni, S.; Shen, H.; Arvind, A.; Antoniou, C.; Fung, L.W.M.; Thomas, D.D. Dinitrosyliron Complexes Are the Most Abundant Nitric Oxide-Derived Cellular Adduct: Biological Parameters of Assembly and Disappearance. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2011, 51, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.F.; Malenkova, I.V.; Serezhenkov, V.A. Iron Catalyzes Both Decomposition and Synthesis ofS-Nitrosothiols: Optical and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies. Nitric Oxide 1997, 1, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.D.; Corey, C.; Hickok, J.; Wang, Y.; Shiva, S. Differential Mitochondrial Dinitrosyliron Complex Formation by Nitrite and Nitric Oxide. Redox Biology 2018, 15, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Kim, E. Synthetic Modeling Chemistry of Iron–Sulfur Clusters in Nitric Oxide Signaling. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2453–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crack, J.C.; Le Brun, N.E. Biological Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Mechanistic Insights from Mass Spectrometry. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2021, 448, 214171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, H.; Kalinowska, M.; Brzoska, K.; Wojciuk, K.; Wojciuk, G.; Kruszewski, M. Nitrosyl Iron Complexes--Synthesis, Structure and Biology. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 8273–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moënne-Loccoz, P. Spectroscopic Characterization of Heme Iron–Nitrosyl Species and Their Role in NO Reductase Mechanisms in Diiron Proteins. Nat Prod Rep 2007, 24, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.T.; Speelman, A.L.; Kozemchak, C.E.; Sil, D.; Krebs, C.; Lehnert, N. The Fe 2 (NO) 2 Diamond Core: A Unique Structural Motif In Non-Heme Iron–NO Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17695–17699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. Synthesis and Reactivity of Non-Heme Iron-Nitrosyl Complexes That Model the Active Sites of NO Reductases. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.D.; Corey, C.; Hickok, J.; Wang, Y.; Shiva, S. Differential Mitochondrial Dinitrosyliron Complex Formation by Nitrite and Nitric Oxide. Redox Biology 2018, 15, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, V.A.; Ivanova, M.V.; Shumaev, K.B.; Dudylina, A.L.; Ruuge, E.K. Generation of Superoxide Radicals by Heart Mitochondria and the Effects of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes and Ferritin. BIOPHYSICS 2021, 66, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukosera, G.T.; Principe, P.; Mata-Greenwood, E.; Liu, T.; Schroeder, H.; Parast, M.; Blood, A.B. Iron Nitrosyl Complexes Are Formed from Nitrite in the Human Placenta. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Bhatla, S.C. Heme Oxygenase-Nitric Oxide Crosstalk-Mediated Iron Homeostasis in Plants under Oxidative Stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2022, 182, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgova, E.N.; Tkachev, N.А.; Paklina, O.V.; Mikoyan, V.D.; Adamyan, L.V.; Vanin, A.F. The Effect of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes with Glutathione and S-Nitrosoglutathione on the Development of Experimental Endometriosis in Rats: A Comparative Studies. European Journal of Pharmacology 2014, 741, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladimir, T.; Anatoly, O.; Larisa, I.; Vladimir, P.; Anna, D.; Аnna, O. Hypothetical Mechanism of Light Action on Nitric Oxide Physiological Effects. Lasers Med Sci 2021, 36, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanin, A.F.; Mikoyan, V.D.; Borodulin, R.R.; Burbaev, D.S.; Kubrina, L.N. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes with Persulfide Ligands: EPR and Optical Studies. Appl Magn Reson 2016, 47, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.F. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes as a “Working Form” of Nitric Oxide in Living Organisms; Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019; ISBN 1-5275-4075-8.

- Chenais, B.; Morjani, H.; Drapier, J.C. Impact of Endogenous Nitric Oxide on Microglial Cell Energy Metabolism and Labile Iron Pool. J.Neurochem. 2002, 81, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasid, S.; Simontacchi, M.; Puntarulo, S. Exposure to Nitric Oxide Protects against Oxidative Damage but Increases the Labile Iron Pool in Sorghum Embryonic Axes. J.Exp.Bot. 2008, ern235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, M.; Lewandowska, H.; Starzyäski, R.; Bartlomiejczyk, T.; Iwanenko, T.; Lipinski, P. Role of Labile Iron Pool in Nitric Oxide-Induced Genotoxicity,.; August 25 2003.

- Kruszewski, M.; Lewandowska, H.; Starzyäski, R.; Bartlomiejczyk, T.; Iwanenko, T.; Drapier, J.C.; Lipinski, P. The Role of Labile Iron Pool and Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes in Nitric Oxide Genotoxicity.; July 3 2004.

- Kruszewski, M.; Lewandowska, H.; Starzynski, R.; Bartomiejczyk, T.; Iwanenko, T.; Drapier, J.; Lipinski, P. Labile Iron Pool, Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes and Nitric Oxide Genotoxicity.; PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD OX5 1GB, ENGLAND, 2004; Vol. 36, pp. S52–S52.

- Lipinski, P.; Starzynski, R.R.; Drapier, J.C.; Bouton, C.; Bartlomiejczyk, T.; Sochanowicz, B.; Smuda, E.; Gajkowska, A.; Kruszewski, M. Induction of Iron Regulatory Protein 1 RNA-Binding Activity by Nitric Oxide Is Associated with a Concomitant Increase in the Labile Iron Pool: Implications for DNA Damage. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2005, 327, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, H. Coordination Chemistry of Nitrosyls and Its Biochemical Implications. In Nitrosyl Complexes in Inorganic Chemistry, Biochemistry and Medicine I; Mingos, D.M.P., Ed.; Structure and Bonding; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014; Vol. 153, pp. 45–114 ISBN 978-3-642-41186-1.

- Lewandowska, H.; Sadło, J.; Męczyńska, S.; Stępkowski, T.M.; Wójciuk, G.; Kruszewski, M. Formation of Glutathionyl Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes Protects against Iron Genotoxicity. Dalton Transactions 2015, 44, 12640–12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, H.; Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Sikorska, K.; Sadło, J.; Dudek, J.; Kruszewski, M. LDL Dinitrosyl Iron Complex: A New Transferrin-independent Route for Iron Delivery in Hepatocytes. BioFactors 2018, 44, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.A.; Ding, H. L-Cysteine-Mediated Destabilization of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes in Proteins. J.Biol.Chem. 2001, 276, 30980–30986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.A.; Eide, L.; Klungland, A.; Ding, H. Reversible Inactivation of E. Coli Endonuclease III via Modification of Its [4Fe-4S] Cluster by Nitric Oxide. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003, 2, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonzetich, Z.J.; Do, L.H.; Lippard, S.J. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes Relevant to Rieske Cluster Nitrosylation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 7964–7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonzetich, Z.J.; McQuade, L.E.; Lippard, S.J. Detecting and Understanding the Roles of Nitric Oxide in Biology. Inorg.Chem. 2010, 49, 6338–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, T.C.; Tonzetich, Z.J.; Reisner, E.; Lippard, S.J. Reactions of Synthetic [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] Clusters with Nitric Oxide and Nitrosothiols. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 15602–15610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinberg, C.E.; Tonzetich, Z.J.; Wang, H.; Do, L.H.; Yoda, Y.; Cramer, S.P.; Lippard, S.J. Characterization of Iron Dinitrosyl Species Formed in the Reaction of Nitric Oxide with a Biological Rieske Center. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 18168–18176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.F. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes and S-Nitrosothiols Are Two Possible Forms for Stabilization and Transport of Nitric Oxide in Biological Systems. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1998, 63, 782–793. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, H.; Kalinowska, M.; Brzóska, K.; Wójciuk, K.; Wójciuk, G.; Kruszewski, M. Nitrosyl Iron Complexes—Synthesis, Structure and Biology. Dalton Transactions 2011, 40, 8273–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Siwkiewicz, H.; Kruszewski, M. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes in Biological Systems; Poland, 2006; p. 36;.

- Lewandowska, H.; Męczyńska, S.; Sochanowicz, B.; Sadło, J.; Kruszewski, M. Crucial Role of Lysosomal Iron in the Formation of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes in Vivo. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2007, 12, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Fujii, S.; Vanin, A.F.; Yoshimura, T. In Vivo Distribution and Behavior of Paramagnetic Dinitrosyl Dithiolato Iron Complex in the Abdomen of Mouse. Free Radical Research 1999, 31, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshin, A.A.; Vanin, A.F.; Orlova, T.R.; Sanina, N.A.; Ruuge, E.K.; Aldoshin, S.M.; Chazov, E.I. Protein-Bound Dinitrosyl–Iron Complexes Appearing in Blood of Rabbit Added with a Low-Molecular Dinitrosyl–Iron Complex: EPR Studies. Nitric Oxide 2007, 16, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Analytical Biochemistry 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, R.; Bailey, R.H.; Burghardt, R.C. Kinetic Analysis of Glutathione in Anchored Cells with Monochlorobimane. Cytometry 1995, 19, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaev, K.B.; Dudylina, A.L.; Ivanova, M.V.; Pugachenko, I.S.; Ruuge, E.K. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes: Formation and Antiradical Action in Heart Mitochondria. BioFactors 2018, 44, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Mellgren, R.L. Calpain Inhibitors and Serine Protease Inhibitors Can Produce Apoptosis in HL-60 Cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1996, 334, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwasa, T.; Sawada, T.; Sakiyama, S. Cysteine Proteinase Inhibitors and Ras Gene Products Share the Same Biological Activities Including Tranforming Activity toward NIH3T3 Mouse Fibroblasts and the Differentiation-Inclucing Activity toward PC12 Rat Pheochromocytoma Cells. Carcinogenesis 1990, 11, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurinov, I.V.; Harrison, R.W. Two Crystal Structures of the Leupeptin-Trypsin Complex. Protein Sci 1996, 5, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, L.; Zheng, H.; Mao, C.; Hu, W.; Xiong, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, C. Application and Interpretation of Current Autophagy Inhibitors and Activators. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013, 34, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindell, J.A. Lysosomal Acidification Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012, 74, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craiu, A.; Gaczynska, M.; Akopian, T.; Gramm, C.F.; Fenteany, G.; Goldberg, A.L.; Rock, K.L. Lactacystin and Clasto-Lactacystin β-Lactone Modify Multiple Proteasome β-Subunits and Inhibit Intracellular Protein Degradation and Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Antigen Presentation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 13437–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squier, M.K.T.; Miller, A.C.K.; Malkinson, A.M.; Cohen, J.J. Calpain Activation in Apoptosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 1994, 159, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.L. Development of Proteasome Inhibitors as Research Tools and Cancer Drugs. Journal of Cell Biology 2012, 199, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, G.; De Llano, J.J.M.; Villarroya, A.; Rivett, A.J.; Knecht, E. Changes in the Proteolytic Activities of Proteasomes and Lysosomes in Human Fibroblasts Produced by Serum Withdrawal, Amino-Acid Deprivation and Confluent Conditions. Biochemical Journal 2003, 375, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Proteasome Inhibitors: Valuable New Tools for Cell Biologists. Trends in Cell Biology 1998, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, M.; Ota, T.; Sasaoka, M.; Katsuta, O.; Shinomiya, K. Chemical Proteasome Inhibition as a Novel Animal Model of Inner Retinal Degeneration in Rats. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, M.; Beaujouin, M.; Rickardson, L.; Havelka, A.M.; Larsson, R.; Westman, J.; Liaudet-Coopman, E.; Linder, S. Induction of the Lysosomal Apoptosis Pathway by Inhibitors of the Ubiquitin-proteasome System. Intl Journal of Cancer 2009, 124, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frase, H.; Hudak, J.; Lee, I. Identification of the Proteasome Inhibitor MG262 as a Potent ATP-Dependent Inhibitor of the Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Lon Protease. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 8264–8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujols, L.; Fernández-Bertolín, L.; Fuentes-Prado, M.; Alobid, I.; Roca-Ferrer, J.; Agell, N.; Mullol, J.; Picado, C. Proteasome Inhibition Reduces Proliferation, Collagen Expression, and Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Nasal Mucosa and Polyp Fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012, 343, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S. Cell-Penetrating Inhibitors of Calpain. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1991, 16, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D. Proteinase and Peptidase Inhibition: Recent Potential Targets for Drug Development. Drug Discovery Today 2002, 7, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.F. Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes and S-Nitrosothiols Are Two Possible Forms for Stabilization and Transport of Nitric Oxide in Biological Systems. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 1998, 63, 782–793. [Google Scholar]

- Vanin, A.F.; Serezhenkov, V.A.; Mikoyan, V.D.; Genkin, M.V. The 2.03 Signal as an Indicator of Dinitrosyl-Iron Complexes with Thiol-Containing Ligands. Nitric.Oxide. 1998, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, P.; Lewandowska, H.; Drapier, J.C.; Starzyäski, R.; Bartlomiejczyk, T.; Kruszewski, M. Increase in Labile Iron Pool (LIP) Level and Generation of EPR-Detectable Dinitrosyl-Non-Heme Iron Complexes in L5178Y Cells Exposed to Nitric Oxide. Possible Role of LIP as a Source of Iron for DNIC Formation.; September 5 2003.

- Lee, M.; Arosio, P.; Cozzi, A.; Chasteen, N.D. Identification of the EPR-Active Iron-Nitrosyl Complexes in Mammalian Ferritins. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 3679–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, H.; Stępkowski, T.M.; Sadło, J.; Wójciuk, G.P.; Wójciuk, K.E.; Rodger, A.; Kruszewski, M. Coordination of Iron Ions in The Form of Histidinyl Dinitrosyl Complexes Does Not Prevent Their Genotoxicity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2012.

- Cesareo, E.; Parker, L.J.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Nuccetelli, M.; Mazzetti, A.P.; Pastore, A.; Federici, G.; Caccuri, A.M.; Ricci, G.; Adams, J.J.; et al. Nitrosylation of Human Glutathione Transferase P1-1 with Dinitrosyl Diglutathionyl Iron Complex in Vitro and in Vivo. J.Biol.Chem. 2005, 280, 42172–42180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, F.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Caccuri, A.M.; Antonini, G.; Turella, P.; Stella, L.; Lo Bello, M.; Federici, G.; Ricci, G. The Specific Interaction of Dinitrosyl-Diglutathionyl-Iron Complex, a Natural NO Carrier, with the Glutathione Transferase Superfamily: Suggestion for an Evolutionary Pressure in the Direction of the Storage of Nitric Oxide. J.Biol.Chem. 2003, 278, 42283–42293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.F. Physico-Chemistry of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes as a Determinant of Their Biological Activity. IJMS 2021, 22, 10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

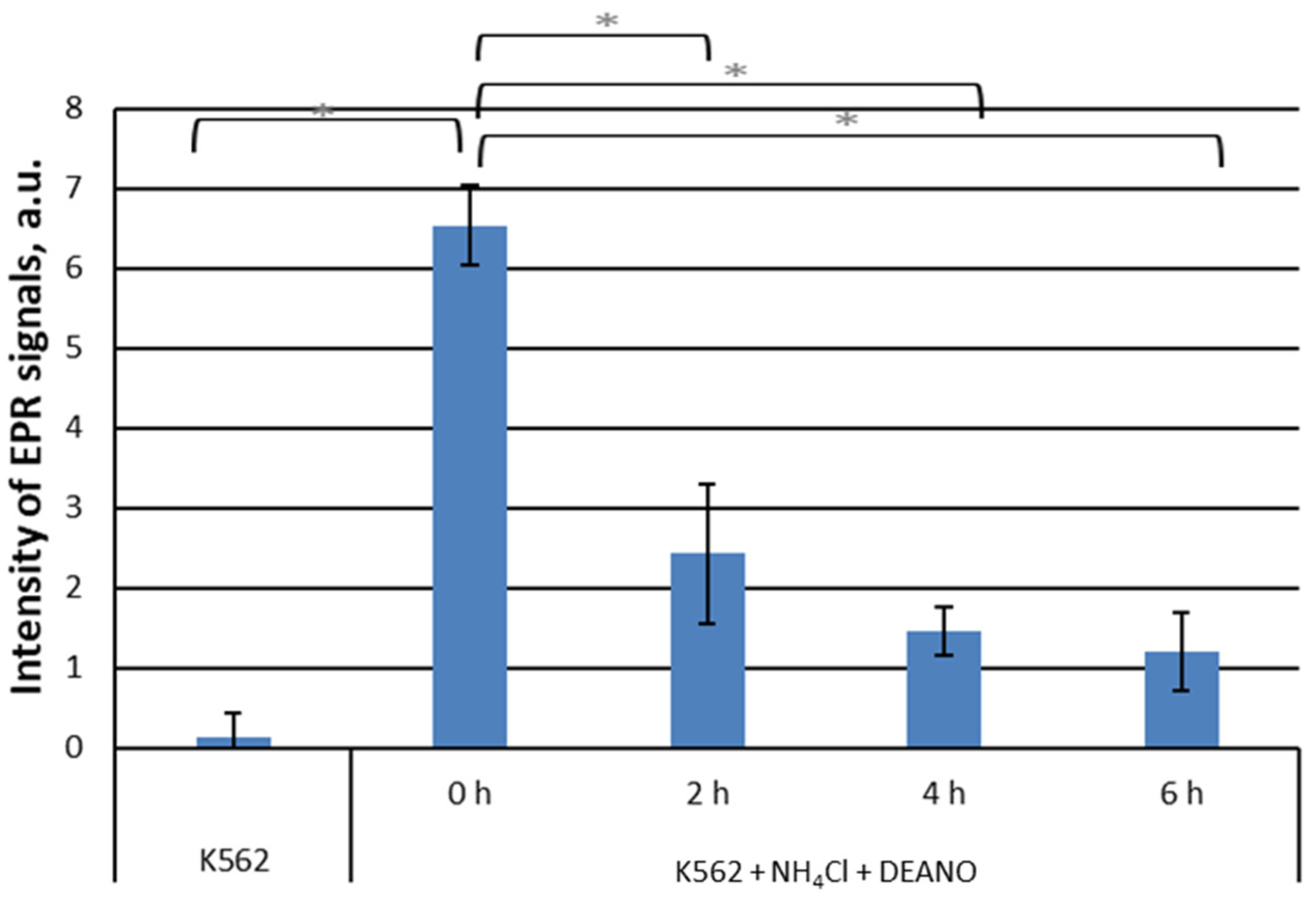

Figure 1.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 15 mM NH4Cl for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 15 mM NH4Cl for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

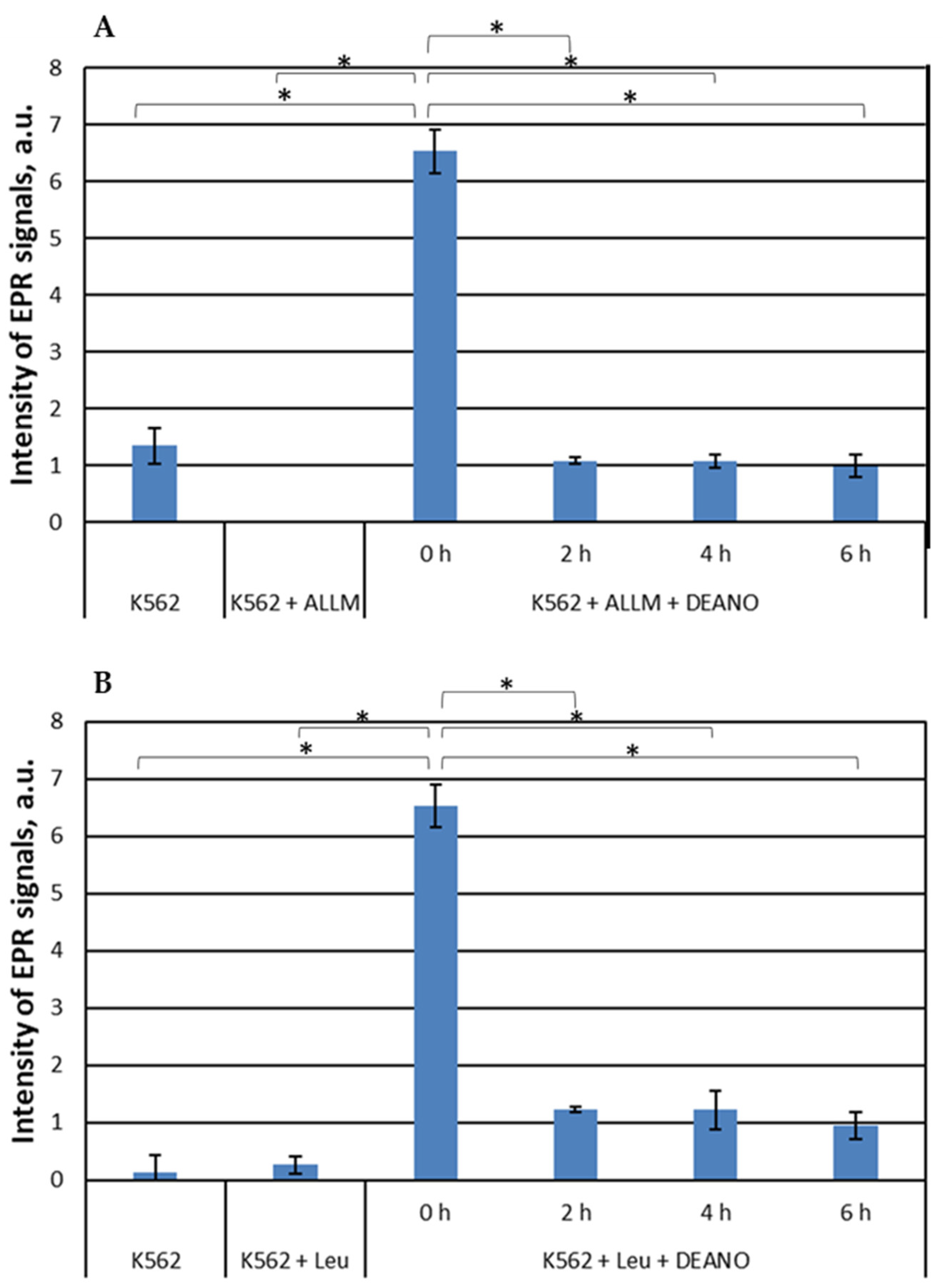

Figure 2.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 50 µM ALLM (a) or 100 µM leupeptin (b) for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 50 µM ALLM (a) or 100 µM leupeptin (b) for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

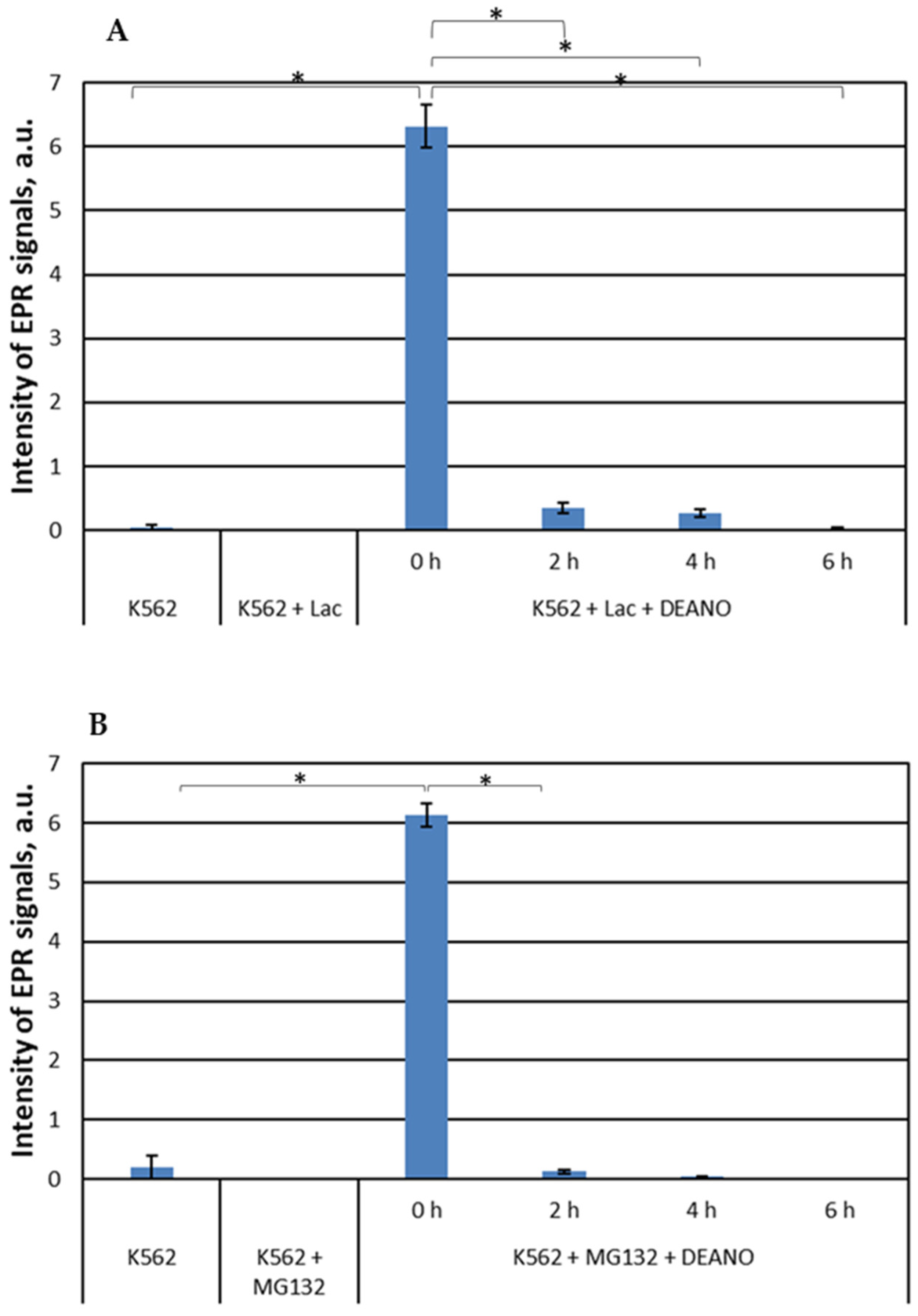

Figure 3.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 15 mM (a) 20µM lactacystin and (b) 25 µM MG132 for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 15 mM (a) 20µM lactacystin and (b) 25 µM MG132 for indicated time (0, 2, 4, 6 h) and then treated with 70 μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C; mean ± SD, n=3, * denotes statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Cellular level of GSH in DEANO-treated cells previously treated with NAC or BSO. GSH levels were estimated with the monochlorobimane method; mean ± SD, n=3; * denotes statistically significant difference versus not treated control cells, P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Cellular level of GSH in DEANO-treated cells previously treated with NAC or BSO. GSH levels were estimated with the monochlorobimane method; mean ± SD, n=3; * denotes statistically significant difference versus not treated control cells, P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Intensity of EPR signal in cells differing in glutathione level. *denotes statistical significance between the marked levels, P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Intensity of EPR signal in cells differing in glutathione level. *denotes statistical significance between the marked levels, P < 0.05.

Figure 7.

The levels of GSH and total thiols in cellular subfractions.

Figure 7.

The levels of GSH and total thiols in cellular subfractions.

Figure 8.

The intensity of the EPR signal in individual cell fractions. Cell homogenate was treated with 70 μM DEANO.

Figure 8.

The intensity of the EPR signal in individual cell fractions. Cell homogenate was treated with 70 μM DEANO.

Figure 9.

EPR spectra: K562 cells K562 cells overexpressing the heavy chain of ferritin (FERH). The cells were treated with 70 μM DEANO).

Figure 9.

EPR spectra: K562 cells K562 cells overexpressing the heavy chain of ferritin (FERH). The cells were treated with 70 μM DEANO).

Figure 10.

Shape of EPR spectra. Inhibition of EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 10mM NH4Cl for 2, 4, and 6 h and then treated with 70μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C.

Figure 10.

Shape of EPR spectra. Inhibition of EPR signal induction in K562 cells incubated with 10mM NH4Cl for 2, 4, and 6 h and then treated with 70μM DEANO for 15 min at 37°C.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).