Introduction

Cell cycle is a rhythmic process of cell proliferation, which plays a crucial role in maintaining the normal growth and division of the cell (Jakoby and Schnittger, 2004). The eukaryotic cell cycle is generally divided into four phases: DNA synthesis phase (S), mitotic phase (M), and two gap phases (G1 and G2), and progression through each phase is tightly regulated and highly orchestrated in the cellular processes. Cell cycle progression in all eukaryotes is controlled by an intricate mechanism involving cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) as well as other factors (Matthews et al., 2022). As part of their pathogenesis, many viruses are known to have evolved multiple strategies to manipulate host cell cycle progression by regulating cyclins and CDKs expression (Adeyemi and Pintel, 2014; Wang et al., 2018), which may inhibit early death of infected cells, thereby allowing cells to escape from immune defenses and promoting viral assembly (Davy and Doorbar, 2007; Caffarelli et al., 2013). Viral infection induces cell cycle arrest in G1, S, or G2 / M phases to exploit the host cell synthesis machinery, utilize cellular DNA replication material, utilize cytoskeletal transport, or evade innate immune sensing (Spector, 2015; Wang et al., 2018);(Su et al., 2021; Bagga and Bouchard, 2014; Danquah et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2022; Bressy et al., 2019).

Baculoviruses are rod-shaped nucleocapsid viruses with circular double-stranded DNA genomes. They are specific pathogens of insects, especially Lepidoptera insects (Rohrmann, 2019). The life cycle of a canonical baculovirus has two divergent virion morphologies, including occlusion derived virus (ODV) and budded virus (BV). ODVs are occluded by a protein matrix, forming occlusive bodies (OBs). Upon ingestion of food contaminated with OBs, ODVs are released by the midgut alkaline pH, initiating a primary infection by infecting epithelial cells of the midgut. The BVs are produced from the infected midgut epithelial cells and disperse to infect other cells during the systemic phase of infection (Blissard and Theilmann, 2018). There are increasing pieces of evidence that baculovirus infection actively manipulates cell cycle progression to provide favorable conditions for their own replication. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) (Ikeda and Kobayashi, 1999), and Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV) (Xiao et al., 2021) infection elicit cell cycle arrest in S or G2/M phase via multiple viral genes or viral proteins expression, such as immediate early gene ie2 (Prikhod’ko and Miller, 1998), late expression factor gene lef-11 (Dong et al., 2022), structural protein gene ODV-EC27 (Belyavskyi et al., 1998), and inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) (Xiao et al., 2021). In the baculovirus expression system (BES), although AcMNPV can establish infection in cells at different cell cycle phases and induce cell cycle arrest in the S phase or G2/M phase, infecting G1 or S phase cells can arrest cells in the S phase more rapidly (Saito et al., 2002). In addition, AcMNPV infection of G1 phase cells can yield a higher yield of progeny virus BV than other phases (Zhang et al., 2012). Thus, different phases of the cell cycle exhibit varying susceptibility to viral infection.

Baculoviruses are highly pathogenic and can cause epidemics of viral diseases, they have been used as bioinsecticides for pest control (Lacey et al., 2015). In some cases, however, baculovirus infection does not necessarily exhibit as an acute infection leading to insect death but instead establishes a covert infection with no apparent symptoms (Williams et al., 2017). Latent infection refers to a covert infection in which the virus has low transcriptional activity and does not produce infectious virions (Cabodevilla et al., 2011). Latent infections of baculoviruses have been reported to be prevalent in insect populations in the field (Burden et al., 2003; Vilaplana et al., 2010), which can severely limit the application range and insecticidal efficiency of baculovirus insecticides.

During viral latency, although no infectious virus can be detected, the viral genome is present in the host and relies on the DNA replication machinery of the host cell for transcription and translation (Sun et al., 2014; Dabral et al., 2019). It has been reported that Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) express certain viral latency-related genes, such as latent membrane proteins and latency-associated nuclear antigens, which can regulate the host cell cycle progression, induce G1 phase arrest or promote G1/S transition, leading to changes in cell proliferation rate and abnormal cell proliferation of latently infected cells (Schang et al., 1996; An et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2019; Kang and Kieff, 2015). Therefore, hijacking and altering the cell cycle are important for the virus to establish latent infection. However, little is known about the effect of baculovirus latent infection on cell cycle progression in insect hosts.

Latent infected cells often develop resistance to subsequent infections with the same or homologous viruses (a phenomenon also known as superinfection exclusion) (Weng et al., 2009). Neither gene expression nor genome replication of the superinfecting virus occurred (Laliberte and Moss, 2014). Superinfection exclusion may occur at different infection stages after virus infection, such as membrane fusion, virion attachment, invasion, and DNA replication (Laliberte and Moss, 2014; Biryukov and Meyers, 2018; Zhang et al., 2017), and seems to be a prerequisite for the maintenance of viral latency (Berngruber et al., 2010). Beperet et al. found that the homologous superinfection exclusion depends on the time interval between infections, and the instantaneous window within the interval allowed for specific heterospecific alpha-baculoviruses superinfection (Beperet et al., 2014). Therefore, the interaction between latently infected virus and cells and the mechanism of superinfection exclusion are complicated, and the effect of baculovirus latent infection on insect cell cycle progression needs to be further studied.

Previously, Spodoptera exigua multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (SeMNPV) latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells were established by infecting Spodoptera exigua Se301 cells with undiluted passaged SeMNPV (Weng et al., 2009). P8-Se301-C1 cells harbored partial SeMNPV genome and some SeMNPV transcripts. The cells showed a slower growth rate than Se301 cells and displayed inhibition to SeMNPV superinfection but not to AcMNPV infection (Weng et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2016). In this study, to understand the effect of latently infected baculovirus on insect cell cycle progression, flow cytometry was used to compare the cell cycle profiles of Se301 cells and latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells, as well as the cell cycle characteristics of cells infected with homologous SeMNPV and heterologous AcMNPV. Further analysis of the sensitivity of P8-Se301-C1 cells in different cell cycle phases to SeMNPV supinfection showed that G1 phase infection and G2/M phase arrest could promote SeMNPV replication, and therefore alleviate the inhibition of homologous virus superinfection. These findings will contribute to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which latently infected viruses regulate cell cycle progression, and provide new strategies for overcoming baculovirus superinfection exclusion and developing efficient baculovirus insecticides.

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Cells and Virus Infection

The cells, including S. exigua Se301 cells, S. frugiperda Sf9 cells, and SeMNPV latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells (Weng et al., 2009), were maintained at 27℃ in Grace’s medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ExCell Bio, Shanghai, China) and a mixture of penicillin and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

The SeMNPV US1 strain was propagated in S. exigua larvae following the method (Arrizubieta et al., 2014). Briefly, fourth instar larvae were fed with an artificial diet contaminated with SeMNPV OBs, and hemolymph was collected as the initial virus inoculum to infect Se301 cells. Four days after infection, the supernatant containing SeMNPV BV was used for subsequent virus infection.

The AcMNPV-recombinant virus vAcPH-GFP (defined as vAcWT) was constructed by modifying the AcMNPV bacmid by insertion of the AcMNPV polh gene and the enhanced green fluorescence protein gene (egfp) to the polh locus (Wu et al., 2006). The BAC/PAC DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) was used to extract vAcWT Bacmid DNA from Escherichia coli DH10B, and 2 μg of vAcWT Bacmid DNA was transfected into 2×106 Sf9 cells. The cell supernatant containing vAcWT BV at 96 hours post-transfection (h p.t.) was collected as the initial virus inoculum to infect Sf9 cells, and the supernatant obtained 4 days after infection was used for subsequent virus infection.

Cells were infected with SeMNPV at an MOI of 1 or AcMNPV at an MOI of 10, respectively. After virus adsorption for 1 h at 27℃, the cells were washed once with serum-free medium, and fresh medium was added (defined as 0 h post-infection, h p.i.). The infected cells were collected at the designated time points for subsequent experiments. Virus titers were determined by tissue culture infectious dose 50% (TCID50) assay.

1.2. Cell Cycle Synchronization

The cell cycle inhibitors hydroxyurea and nocodazole (both from Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were used for cell synchronization. Cells (Se301 or P8-Se301-C1) were cultured in insect medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h to synchronize the cells to late G1 phase. The medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). Fresh insect medium was added to release the cells for 6 h to synchronize G1 phase cells into S phase. After 18 h of release, P8-Se301-C1 cells were further cultured with medium containing 7 μg/mL nocodazole for an additional 12 h to synchronize the cells in the G2/M phase.

1.3. Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

The cell cycle was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis after propidium iodide (PI) staining. The cells were harvested, washed three times with PBS (pH 7.2), and then fixed with 70% pre-cooled ethanol at 4℃ for 24 h. After staining with PBS containing 50 µg/ml PI (BD, New York, USA) and 20 µg/ml RNase for 30 min, the fluorescence intensity was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto, BD, New York, USA). A minimum of 15,000 cell counts were performed for each sample. Data analysis was performed using ModFit LT (version 5.0, Verity Software House). All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

1.4. Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The transcriptional expression levels of cellular genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Cellular RNA was extracted using RNA-Quick Purification Kit (ESscience, Shanghai, China). RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using StarScript II RT Mix with gDNA Remover Kit (GenStar, Beijing, China). QRT-PCR was conducted using 2×RealStar Fast SYBR qPCR Mix (Low ROX) (GenStar, Beijing, China) and analyzed with QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, USA). The PCR reaction program was as follows: 95℃ for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95℃ for 15 s and 60℃ for 30 s. The relative expression of the target gene was quantified by 2^-ΔΔCt method with S. exigua 18S rRNA gene as the endogenous reference (Zhu et al., 2014). The primer sequences used in target genes amplification are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

1.5. Viral Production Analysis in Infected Cells

The copy number of essential gene

Se67 (a single-copy gene of SeMNPV) was quantified by qRT-PCR to determine the amount of virus or intracellular viral DNA content. The

Se67 gene was amplified by PCR using SeMNPV DNA as a template, and the PCR product was cloned into the pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) to generate plasmid pMD18-T-

Se67. After transformation into

E. coli DH5α, pMD18-T-

Se67 plasmid DNA was extracted using plasmid Mini Kit I (OMEGA, Massachusetts, USA). Then 10 × serial gradient dilution of the plasmid DNA was used as a template for qRT-PCR analysis. The qRT-PCR reaction procedure was the same as described in 1.4 above. A standard curve was prepared from the Ct value and the common log value (lg value) of the

Se67 gene copy number (

Supplementary Figure S1).

P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized to the specific cell cycle phase by drug treatment, the cells were then pre-cooled at 4℃ and then incubated with SeMNPV (MOI = 1) at 4℃ for 60 min. After the cells were washed twice with cold PBS to remove the unbound virus, the total cellular DNA was extracted using the MiniBEST Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit Ver. 5.0 kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) and used as the template for qRT-PCR analysis. According to the Ct value detected by qRT-PCR analysis, and the standard curve of pMD18-T-Se67 plasmid DNA, the copy number of the viral DNA genome was calculated to determine the amount of virus adsorbed on the cell surface.

P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized to the specific cell cycle phase by drug treatment and were then infected with SeMNPV (MOI = 1) for 48 h at 27℃. The infected cells were harvested, and the total cellular DNAs were extracted as the template for qRT-PCR analysis. According to the Ct value detected by qRT-PCR analysis and the standard curve of pMD18-T-Se67 plasmid DNA, the copy number of the viral DNA genome was calculated to analyze the viral genomic DNA replication.

P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized to the specific cell cycle phase by drug treatment and then infected with SeMNPV (MOI = 1) at 27℃. At the indicated time points, the morphological and cytopathic effects of the cells were observed by phase contrast microscopy. The culture supernatant containing BVs was harvested and the BV genomic DNA of 100 μL of supernatant was extracted using the MiniBEST Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit Ver.5.0 kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). According to the Ct value detected by qRT-PCR analysis and the standard curve of pMD18-T-Se67 plasmid DNA, the copy number of the viral DNA genome was calculated to analyze the progeny BV yield in the supernatant.

1.6. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical analysis. For each experiment, a student’s t-test was used for statistical comparison, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

2. Results

2.1. Cell Cycle Distribution and Differences between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 Cells

The cell cycle distribution of Se301 cells and P8-Se301-C1 cells was determined using flow cytometry. The results showed that the two cell types showed different cell cycle distributions during culture (

Figure 1A–C). After subculture (0 h), the proportion of P8-Se301-C1 cells in the G1 phase (41.97±0.48%) was significantly higher than that of Se301 cells (32.95±1.67%) (

p < 0.01). Moreover, the proportions of S phase cells (27.04±0.47%) and G2/M phase cells (30.9±0.38%) in P8-Se301-C1 were significantly lower than those in Se301 cells (31.69±0.60% and 35.36±1.07%, respectively) (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 1D). At 30 h after subculture, the proportion of Se301 cells in the S phase decreased to 24.27±0.66%, while the proportion of P8-Se301-C1 cells in the S phase increased to 37.85±0.71% (

Figure 1B), implying a different progression between Se301 cells and P8-Se301-C1 cells in S phase.

Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells were arrested at the late G1 phase by hydroxyurea treatment to further analyze cell cycle characteristics (

Figure 1E). Upon release culture, the number of synchronized cells in the G1 phase rapidly declined and accumulated in the S phase within 6 h (Se301 cells) or 12 h (P8-Se301-C1 cells). As the culture progressed, cells in the S phase gradually decreased, while cells in the G2/M phase began to accumulate and reached a peak at 14-16 h (Se301 cells) or 20-22 h (P8-Se301-C1 cells) after release, respectively (

Figure 1F,G). The results indicate a 6 h difference between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells in the progression time from late G1 to G2/M phase (S phase).

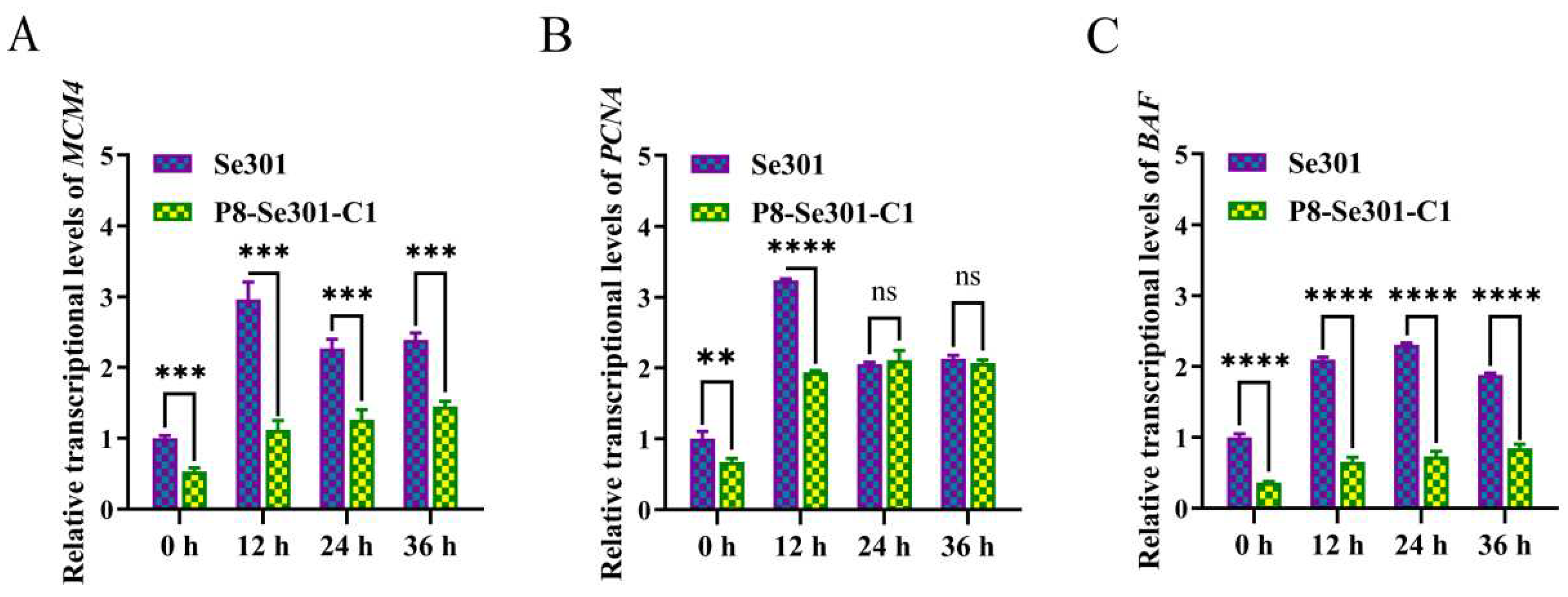

2.2. Differential Expression of DNA Replication-Related Genes in Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 Cells

To further clarify the difference in S phase progression between Se301 cells and P8-Se301-C1 cells, we examined the transcriptional expression levels of key genes involved in DNA replication in the two cells. The results of qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of

MCM4,

PCNA (at 0 h and 12 h), and

BAF genes in P8-Se301-C1 cells were markedly lower than those in Se301 cells (

p < 0.05) within 36 h after release of late G1 synchronized cells (

Figure 2). This suggests that the slower progression of the S phase in P8-Se301-C1 cells may be attributed to the down-regulation of DNA replication-related genes.

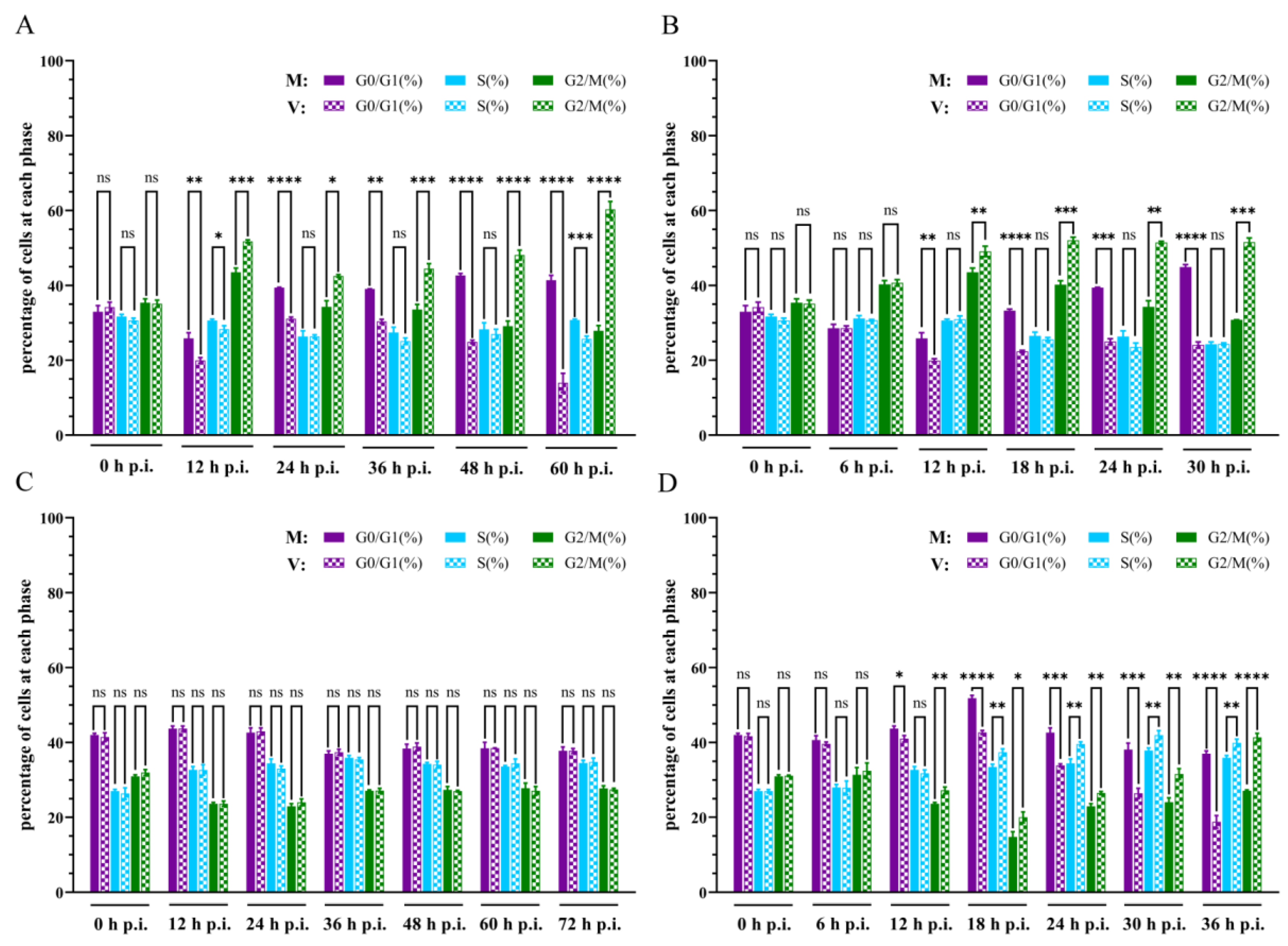

2.3. Effect of Homologous SeMNPV and Heterologous AcMNPV Virus Infection on the Cell Cycle of Se301 Cells and P8-Se301-C1 Cells

To investigate the effect of baculovirus infection on the cell cycle

, Se301 cells and P8-Se301-C1 cells were infected with homologous virus SeMNPV and heterologous baculovirus vAcWT (a recombinant AcMNPV), respectively. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that infection of Se301 cells with SeMNPV or vAcWT resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of cells in the G2/M phase at 12 h p.i. compared with the mock-infected cells (

p < 0.05). Moreover, G2/M accumulation continued to increase over the course of the infection (

Figure 3A,B). However, SeMNPV infection did not result in the cell cycle change of P8-Se301-C1 cells, and the proportions of G1, S, or G2/M phases were comparable to those in mock-infected cells (

Figure 3C). Nonetheless, vAcWT infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells resulted in an increase in the proportion of G2/M phase cells at 12 h p.i. and further accumulated with the time of infection. In addition, S phase cells were also significantly accumulated at 18 h p.i. and persisted until 72 h p.i. (

Figure 3D). These results demonstrate that both SeMNPV and vAcWT can induce G2/M phase arrest in Se301 cells, while heterologous vAcWT, but not homologous SeMNPV, can induce cell cycle arrest in P8-Se301-C1 cells.

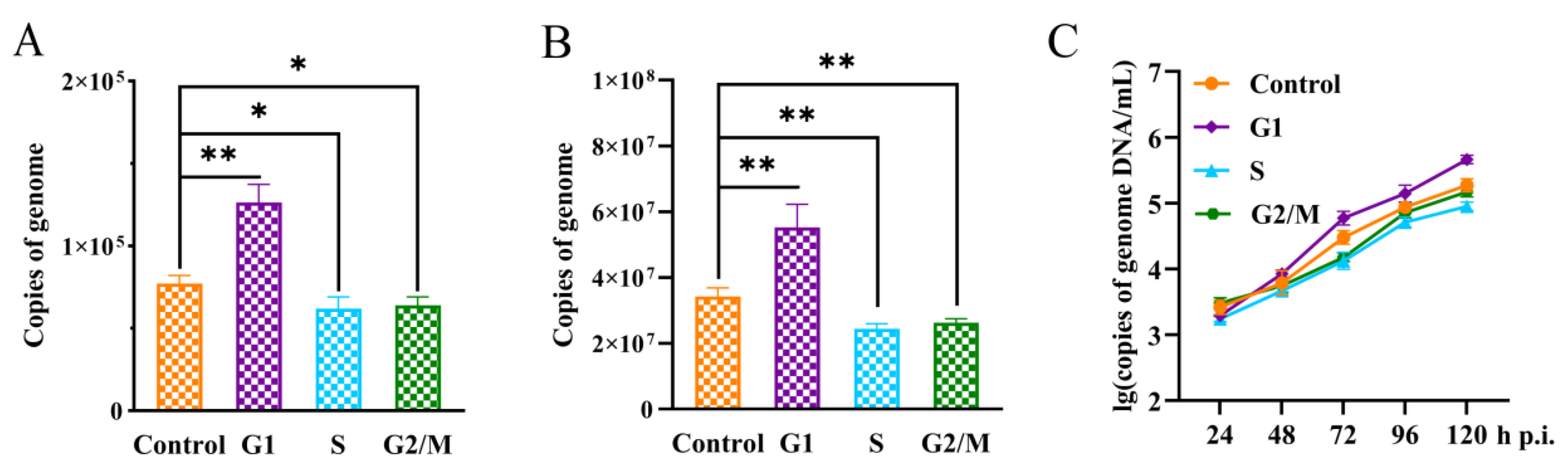

2.4. P8-Se301-C1 Cells in G1 Phase Were more Susceptible to SeMNPV Superinfection

In order to reveal the response of different specific cell cycle phases to SeMNPV superinfection, P8-Se301-C1 cells were infected with SeMNPV after being synchronized to G1, S, and G2/M phases, respectively. The adsorption of viral particles on the cell surface, the replication of intracellular viral DNA, and the viral production of progeny were quantitatively analyzed by qRT-PCR. Compared with unsynchronized cells, the amount of virus adsorption and intracellular viral DNA replication in G1 phase cells were significantly increased (

p < 0.05), while those in S and G2/M phase cells were significantly decreased (

p < 0.05) at 48 h p.i. (

Figure 4A,B). In addition, the detection of BV production in the supernatant of infected cells revealed that the BV production in synchronized cells in G1, S, and G2/M phases was comparable to that in unsynchronized cells at 24 h p.i. (

p > 0.05). However, at 120 h p.i., the BV production in the G1 phase cells was significantly higher than that in unsynchronized cells (

p < 0.05), while the BV production in S and G2/M phase cells decreased (

Figure 4C). These results suggested that the sensitivity of P8-Se301-C1 cells in G1, S, and G2/M phases to SeMNPV infection was different. G1 phase was more advantageous to SeMNPV infection, and could partially alleviate the exclusion effect of SeMNPV superinfection in P8-Se301-C1 cells.

2.5. SeMNPV Superinfection of G1 Phase P8-Se301-C1 Cells Induced G2/M Phase Arrest and Downregulated Cyclin B and CDK1 Expression

The cell cycle arrest of SeMNPV infected P8-Se301-C1 cells at different cell cycle phases was analyzed. Flow cytometry analysis showed that SeMNPV infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells in the G1 phase did not cause significant changes in the cell cycle within 24 h p.i.. However, the proportion of G2/M phase increased in the infected cells was higher than that in the mock infected cells at 48 h p.i. (

p < 0.05), and continued to increase until 72 h p.i. (

Figure 5A). Nevertheless, SeMNPV infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells in either the S phase or the G2/M phase did not result in considerable differences in cell cycle distribution (

Figure 5B,C). These results suggest that SeMNPV could induce the accumulation of P8-Se301-C1 cells in the G2/M phase to a certain extent by infecting cells in the G1 phase rather than the S or G2/M phase.

Cyclin B and CDK1 are key factors regulating G2 phase progression and M phase entry of cells. The results of qRT-PCR analysis showed that compared to the mock-infected cells, the transcription expression level of

Cyclin B and

CDK1 were significantly downregulated in Se301 cells and G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells 48 h after SeMNPV infection (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5D,F). However, the transcriptional expression of

Cyclin B and

CDK1 did not change significantly after infection of unsynchronized, S phase, or G2/M phase P8-Se301-C1 cells (

Figure 5E,G,H). The results showed that infection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells with SeMNPV inhibited

Cyclin B and

CDK1 expression as did infection of Se301 cells.

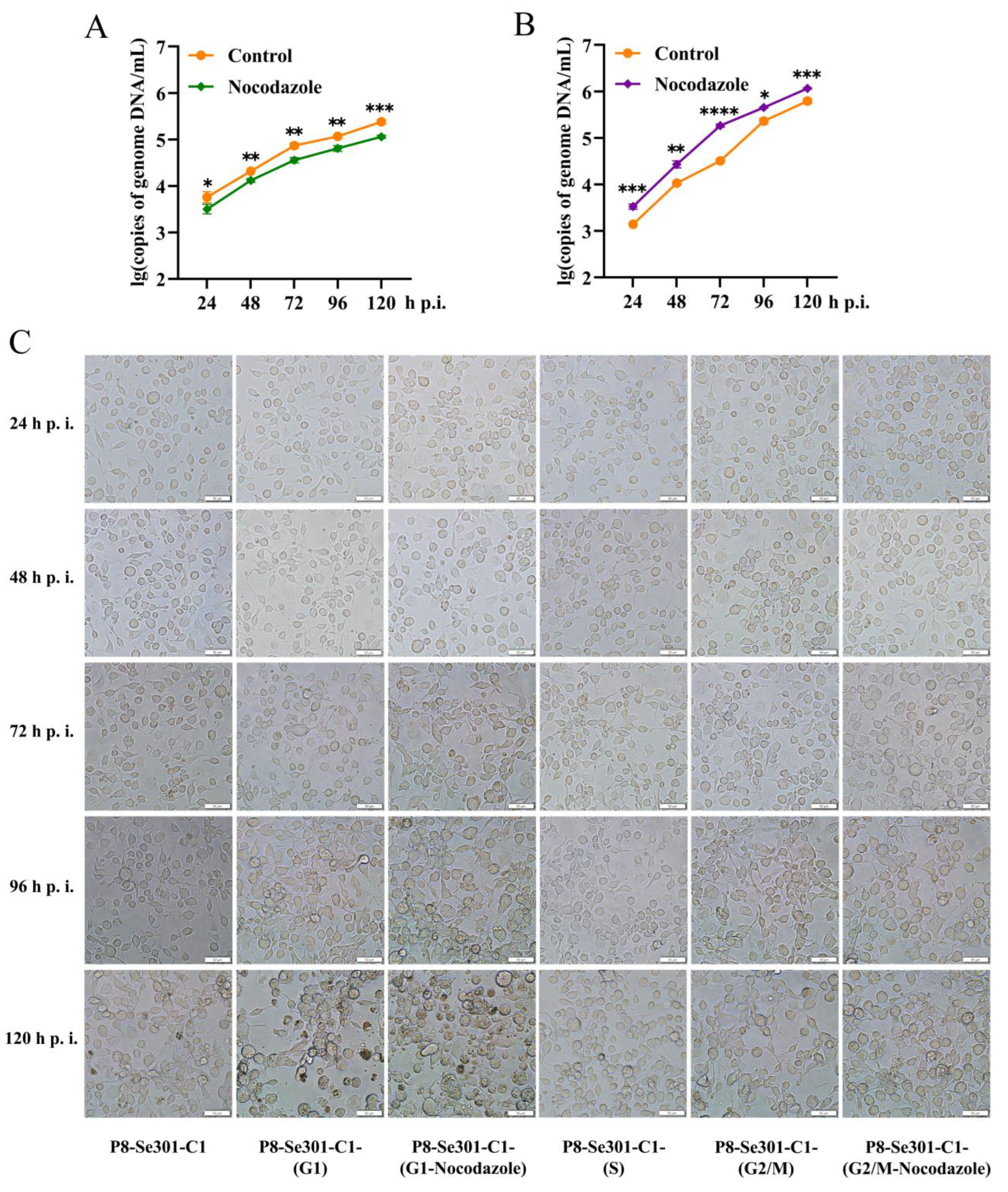

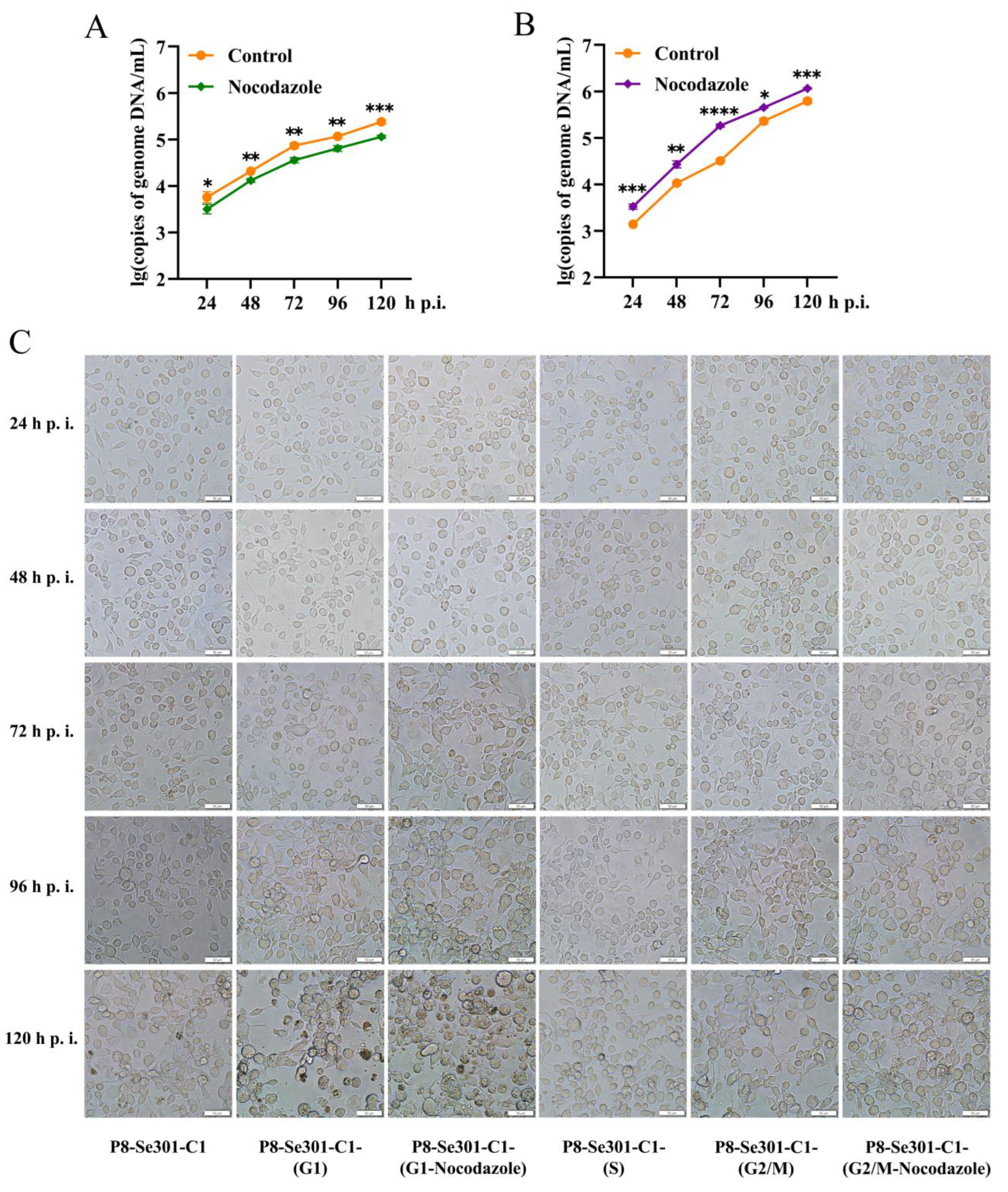

2.6. G2/M Phase Arrest Was Required for SeMNPV Replication in P8-Se301-C1 Cells

To understand whether G2/M phase arrest is essential for virus multiplication in P8-Se301-C1 cells, progeny virus production was determined by infecting P8-Se301-C1 cells in G2/M phase with SeMNPV and subsequently arresting cells in G2/M phase with nocodazole treatment. SeMNPV infected cells without nocoodazole treatment were used as controls. The results of qRT-PCR analysis indicated that BV production was not increased but decreased compared with control cells (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 6A). In contrast, when P8-Se301-C1 cells were infected in G1 phase and then arrested in G2/M phase by nocodazole treatment, the production of BV significantly increased (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 6B). It was suggested that G1 phase infection and G2/M arrest are both necessary for SeMNPV multiplication in P8-Se301-C1 cells.

Light microscopy showed that no significant morphological differences were observed in SeMNPV infected P8-Se301-C1 cells at G1, S, G2/M phase at 24 h p.i.. At 96 h p.i., after infection of unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells with SeMNPV, the cells showed mild cytopathic effects, but cells containing OBs were not observed. In contrast, cells infected in the G1 phase showed more apparent cytopathic effects (with or without nocodazole treatment), most of which became round, enlarged, aggregated, and formed multicellular. Moreover, polyhedra appeared in a few cells, and the number of OBs containing cells in infected cells treated with nocodazole (about 10%) was higher than that in untreated infected cells (less than 5%). At 120 h p.i., less than 10% of the infected unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells contained OBs. In contrast, of the G1 phase infected cells, the OBs containing cells in the nocodazole treated and nocodazole untreated cells are about 24.1% and 14.1%, respectively. In addition, until 120 h p.i., no polyhedra were observed in SeMNPV infected cells in S phase and G2/M phase cells (with or without nocodazole treatment), except for cytopathic effects such as cell rounding and aggregation (

Figure 6C).

3. Discussion

The cell cycle plays a crucial role in maintaining normal cell growth and division (Jakoby and Schnittger, 2004), and many viral infections can modulate the cell cycle, leading to changes in cell cycle progression that promote viral replication. Therefore, hijacking and altering the cell cycle are essential for the virus to establish and maintain latent infection (Yin et al., 2019; Berngruber et al., 2010). However, little is known about the effect of baculovirus latent infection as well as baculovirus superinfection on host cell cycle progression regulation. In this study, we reveal that baculovirus latent infection interfered with the cell cycle progression, resulting in prolonged cell cycle in SeMNPV latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells. SeMNPV superinfection failed to induce G2/M phase arrest in P8-Se301-C1 cells. Furthermore, specific G1 phase infection and G2/M phase arrest favouring SeMNPV replication are effective ways to alleviate SeMNPV superinfection exclusion in P8-Se301-C1 cells. The study contributes to a better understanding of the interplay between baculovirus latent infection and host cell cycle regulation and provides new insights into the mechanism of overcoming antiviral effects.

The cell cycle distribution of

S. exigua cells was comparable in proportions to G1, S, and G2/M phases (

Figure 1D), similar to that of

S. frugiperda Sf9 cells (Braunagel et al., 1998). In contrast, the cell cycle distributions of

Helicoverpa armigera Hz-AM1 cells and

B. mori BmN-SWU1 cells showed differences in cell cycle distribution, with G1 phase cells predominating in the former and G2/M phase cells in the latter (Zhou et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2021). Cell cycle distribution and progression can vary owing to biological characteristics differences of cell types or culture methods (Whitfield et al., 2002; Spencer et al., 2013; Yano et al., 2015).

The cell cycle progression of SeMNPV latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells was perturbed. The cell cycle distribution of P8-Se301-C1 cells was different from that of Se301 cells, with a higher proportion of G1 phase and prolonged S phase (

Figure 1D). This result of cell cycle prolongation of P8-Se301-C1 cells is consistent with our previous study showing that P8-Se301-C1 cells have a slower growth rate (Weng et al., 2009). The prolonged S phase of P8-Se301-C1 cells may be related to impaired DNA synthesis. The expression levels of host DNA replication-related genes, minichromosome maintenance proteins (MCMs)

MCM4, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (

PCNA), and barrier-to-autointegration factor (

BAF) in P8-Se301-C1 cells were significantly lower than those in Se301 cells (

Figure 2). MCM forms a heterohexamer (MCM2-7) to initiate DNA replication in G1/S phase, while BAF binding to PCNA promotes DNA replication i

n the S phase (Limas and Cook, 2019; Lin et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown that transient inhibition of MCM and PCNA transcription does not affect cell cycle progression from late G1 into S phase, but delays S phase exit (Mukherjee et al., 2009). RNAi knockdown of BAF directly mediates S phase arrest in cells (Lin et al., 2020). During latency, the virus relies on host resources, such as host DNA replication factors, to support its DNA replication (Dabral et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2014), which would inhibit the host cell’s own DNA synthesis (Zou et al., 2018). For example, KSHV encodes LANA that can modulate cellular gene expression, such as upregulate

MCM4 expression, which promotes host cell proliferation during latency (An et al., 2005). It was suggested that the presence of viral genome or transcripts in P8-Se301-C1 cells may delay S phase exit and affect the cell cycle progression by downregulating cellular DNA replication-related genes. The regulation of baculovirus latency-associated genes or transcripts on host cell DNA replication and cell cycle needs to be further elucidated.

Compared with S and G2/M phase, G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells were more susceptible to SeMNPV infection, and the production of progeny BV and OB increased after SeMNPV infection (

Figure 4C and

Figure 6C). Infection efficiency of the virus varies among cells due to the different physiological states of cells at different phases of the cell cycle, including cell activity (Zhang et al., 2012), expression of virus receptors on the cell membrane surface (Xin et al., 2018), and intracellular substance activity (He et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that AcMNPV infection of Sf9 cells in the G1 phase was more efficient, enhanced the expression of recombinant proteins (Saito et al., 2002), as well as increased the production of BV and OB (Zhang et al., 2012). The amount of virus adsorption and intracellular viral DNA replication were significantly increased in G1 phase cells compared with unsynchronized cells and cells in S and G2/M phases (

Figure 4A,B). Similarly, influenza virus infection selectively attached to G1 phase cells due to less membrane stiffness and higher virus binding specificity (Ueda et al., 2013). In addition, G1 phase is the preparatory phase for cellular DNA replication, during which cellular metabolism is active (Icard and Simula, 2022) and membrane transport is enhanced (Boward et al., 2016; Frye et al., 2020), which may facilitate viral nucleocapsid transport across the cell membrane to the nucleus for replication (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, SeMNPV infection in the G1 phase of P8-Se301-C1 cells may promote progeny BV production by increasing the amount of virus adsorbed on the cell surface and viral DNA replication.

Infection of Se301 cells with SeMNPV and vAcWT resulted in G2/M phase arrest (

Figure 3A), consistent with AcMNPV, HaSNPV, and BmNPV infecting their permissive cells (Braunagel et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2021), suggesting that inducing G2/M phase cell cycle arrest may be a common strategy for baculovirus infection. G2/M phase cell cycle arrest can maintain cells in a “pseudo-S phase”, which is more conducive to virus replication, thus avoiding viral replication from competing with cellular DNA replication for nucleotide libraries and reducing the virus reliance on the S phase environment (Chaurushiya and Weitzman, 2009; Flemington, 2001). Moreover, the transcriptional suppression of mitotic genes in G2/M phase cells can inhibit the expression of antiviral genes, allowing the virus to evade antiviral responses and facilitating viral replication and proliferation (Bressy et al., 2019). Furthermore, G2/M phase arrest may also be advantageous for viral transport due to the availability of microtubules or mitotic spindles (Danquah et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2022).

However, SeMNPV infection did not cause G2/M phase arrest in latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells, although AcMNPV infection induced G2/M phase arrest (

Figure 3C,D). Therefore, while P8-Se301-C1 cells were arrested in the G2/M phase by infecting in the specific G1 phase (

Figure 5A), it may create a favorable environment for SeMNPV multiplication and thus alleviate the SeMNPV superinfection exclusion. Cyclin B and CDK1 bind to form maturation promoting factor (MPF), which drives cells from the G2 to M phase by phosphorylated substrate proteins (Ohi and Gould, 1999). Virus infection can reduce

Cyclin B and

CDK1 expression (Xiao et al., 2021), or inhibit Cyclin B1-CDK1 complex formation and nuclear import (Liu et al., 2020). SeMNPV infection G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells could inhibit the transcription levels of

Cyclin B and

CDK1, leading to G2/M phase cell accumulation (

Figure 5C,F). Therefore, these results suggested that SeMNPV infection failure to induce G2/M phase arrest in latently infected cells may be the key event leading to homologous superinfection exclusion.

Nonetheless, G2/M phase arrest alone was not sufficient to relieve the inhibition of SeMNPV superinfection on P8-Se301-C1 cells. Previous study have indicated that G2/M phase arrest induced by nocodazole treatment in BmN-SWU1 cells promotes BmNPV virus proliferation (Xiao et al., 2021). However, induction of G2/M phase arrest in infected cells by treatment with nocodazole did not promote viral DNA replication but reduced BV progeny production (

Figure 6A). Only infection in the G1 phase and arrest in the G2/M phase enhanced BV and OB production (

Figure 6B,C), suggesting that G2/M phase arrest and G1 phase initial infection are beneficial for SeMNPV replication in P8-Se301-C1 cells. Viral infection is associated with viral receptors on the cell membrane surface (Koutsoudakis et al., 2007). The interaction between the virus adsorption protein and the host cell surface adsorption receptor, which serves as the rate-limiting step of virus infection, plays an important role in the process of virus infection. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 interacts with the adsorbed receptors integrin α6/α4 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on the surface of human immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT), leading to the decrease of intracellular adsorbed receptor protein expression and HPV18 superinfection exclusion (Biryukov and Meyers, 2018). We recently clarified that the superinfection exclusion of SeMNPV in P8-Se301-C1 cells has occurred in the adsorption stage (data not shown). So, it is reasonably suggested that the presence of viral genomes and transcripts in P8-Se301-C1 cells (Fang et al., 2016) may lead to a reduction in the amount of virus absorbed on the cell surface, which may be one of the reasons affecting its inhibition of SeMNPV superinfection. Moreover, the amount of virus adsorption increased after SeMNPV infection of G1 phase cells (

Figure 4A), which may be critical for successful superinfection of SeMNPV in P8-Se301-C1 cells. Future studies on the regulation and interaction of host and viral genes and cell surface receptors related to latent infection will help to further reveal the homologous superinfection exclusion and the mechanism of baculovirus latent infection.

Taken together, this study revealed that the cell cycle distribution and S phase duration in SeMNPV latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells were different from those in Se301 cells. Infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells with SeMNPV did not induce G2/M phase arrest as did infection of Se301 cells. When P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized in G1 phase, SeMNPV superinfection could downregulate the expression of

Cyclin B and

CDK1 and induce G2/M phase arrest. In addition, G1 phase infection promoted the amount of viral adsorption on the cell surface and intracellular viral DNA replication of superinfected SeMNPV, and increased the production of BVs and OBs. Moreover, synchronization of SeMNPV-infected G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells in G2/M phase further increased the progeny virus production (

Figure 7). In conclusion, we have proposed an effective strategy to alleviate homologous baculovirus superinfection exclusion in latently infected cells by specific G1 phase infection and G2/M phase arrest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Primer sequences used in this study. Supplementary Figure S1. Standard curve of Se67 gene copy number determined by qRT-PCR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Q.-B.W.; Z.F. and Q.-M.F.; Data curation: Q.-M.F.; Formal analysis: Q.-P.L. and L.-T.T.; Funding acquisition: Q.-B.W.; Investigation: Q.-M.F. and Z.F.; Methodology: Q.-M.F.; Z. F.; L.R.; Q.-P.L. and L.-T.T.; Project administration: Z.F.; Q.-S.W. and Q.-B.W.; Resources: Q.-B.W.; Z.F.; Q.-S.W. and J.-B.Z.;Supervision: Z.F.; Q.-S.W. and Q.-B.W.; Validation: Q.-M.F. and L.R.; Visualization: Q.-M.F.; L.R. and J.-B.Z.; Writing - original draft: Q.-M.F.; Writing - review and editing: Q.-B.W. and Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31760537), Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe JC [2019] 1223), Provincial Program on Platform and Talent Development of the Department of Science and Technology of Guizhou China ([2019] 5617, [2019] 5655).

References

- Adeyemi, R.O.; Pintel, D.J. Parvovirus-induced depletion of Cyclin B1 prevents mitotic entry of infected cells. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10, e1003891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.Q.; Compitello, N.; Horwitz, E.; et al. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus modulates cellular gene expression and protects lymphoid cells from p16 INK4A-induced cell cycle arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 3862–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizubieta, M.; Williams, T.; Caballero, P.; et al. Selection of a nucleopolyhedrovirus isolate from Helicoverpa armigera as the basis for a biological insecticide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, S.; Bouchard, M.J. Cell cycle regulation during viral infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1170, 165–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyavskyi, M.; Braunagel, S.C.; Summers, M.D. The structural protein ODV-EC27 of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus is a multifunctional viral cyclin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 1998, 95, 11205–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beperet, I.; Irons, S.L.; Simón, O.; et al. Superinfection exclusion in alphabaculovirus infections is concomitant with actin reorganization. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3548–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berngruber, T.W.; Weissing, F.J.; Gandon, S. Inhibition of superinfection and the evolution of viral latency. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10200–10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biryukov, J.; Meyers, C. Superinfection exclusion between two high-risk human papillomavirus types during a coinfection. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01993–e01917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blissard, G.W.; Theilmann, D.A. Baculovirus entry and egress from insect cells. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boward, B.; Wu, T.; Dalton, S. Concise review: control of cell fate through cell cycle and pluripotency networks. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunagel, S.C.; Parr, R.; Belyavskyi, M.; et al. Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus infection results in Sf9 cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase. Virology 1998, 244, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bressy, C.; Droby, G.N.; Maldonado, B.D.; et al. Cell cycle arrest in G2/M Phase enhances replication of interferon-sensitive cytoplasmic RNA viruses via inhibition of antiviral gene expression. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01885–e01818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, J.P.; Nixon, C.P.; Hodgkinson, A.E.; et al. Covert infections as a mechanism for long-term persistence of baculoviruses. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabodevilla, O.; Villar, E.; Virto, C.; et al. Intra- and intergenerational persistence of an insect nucleopolyhedrovirus: adverse effects of sublethal disease on host development, reproduction, and susceptibility to superinfection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2954–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarelli, N.; Fehr, A.R.; Yu, D. Cyclin A degradation by primate cytomegalovirus protein pUL21a counters its innate restriction of virus replication. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurushiya, M.S.; Weitzman, M.D. Viral manipulation of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoints. DNA Repair 2009, 8, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabral, P.; Uppal, T.; Rossetto, C.C.; et al. Minichromosome maintenance proteins cooperate with LANA during the G1/S phase of the cell cycle to support viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02256–e02218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, J.O.; Botchway, S.; Jeshtadi, A.; et al. Direct interaction of baculovirus capsid proteins VP39 and EXON0 with kinesin-1 in insect cells determined by fluorescence resonance energy transfer-fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, C.; Doorbar, J. G2/M cell cycle arrest in the life cycle of viruses. Virology 2007, 368, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, M.; et al. Baculovirus LEF-11 interacts with BmIMPI to induce cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase for viral replication. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 188, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Shao, J.; Weng, Q. De novo transcriptome analysis of Spodoptera exigua multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (SeMNPV) genes in latently infected Se301 cells. Virol. Sin. 2016, 31, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemington, E.K. Herpesvirus lytic replication and the cell cycle: arresting new developments. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 4475–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, K.; Renda, F.; Fomicheva, M.; et al. Cell cycle-dependent dynamics of the golgi-centrosome association in motile Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, K.; Keiner, B.; et al. Influenza a virus replication induces cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12832–12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icard, P.; Simula, L. Metabolic oscillations during cell-cycle progression. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 33, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Kobayashi, M. Cell-cycle perturbation in Sf9 cells infected with Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 1999, 258, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakoby, M.; Schnittger, A. Cell cycle and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004, 7, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr virus latent genes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoudakis, G.; Herrmann, E.; Kallis, S.; et al. The level of CD81 cell surface expression is a key determinant for productive entry of hepatitis C virus into host cells. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; et al. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: back to the future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte, J.P.; Moss, B. A Novel Mode of Poxvirus Superinfection Exclusion That Prevents Fusion of the Lipid Bilayers of Viral and Cellular Membranes. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9751–9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limas, J.C.; Cook, J.G. Preparation for DNA replication: the key to a successful S phase. Febs Lett. 2019, 593, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Yu, B.; Wang, X.; et al. K6-linked SUMOylation of BAF regulates nuclear integrity and DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 2020, 117, 10378–10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Kang, J.; et al. The severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus NSs protein interacts with CDK1 to induce G2 cell cycle arrest and positively regulate viral replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01575–e01519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.K.; Bertoli, C.; De Bruin, R.A.M. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Cao, T.V.; Winter, S.L.; et al. Mammalian MCM loading in late-G1 coincides with Rb hyperphosphorylation and the transition to post-transcriptional control of progression into S-phase. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, R.; Gould, K.L. Regulating the onset of mitosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999, 11, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhod’ko, E.A.; Miller, L.K. Role of baculovirus IE2 and its RING finger in cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, G.F. (2019) Baculovirus molecular biology (4th ed.). National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK543458.

- Saito, T.; Dojima, T.; Toriyama, M. The effect of cell cycle on GFPuv gene expression in the baculovirus expression system. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 93, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schang, L.M.; Hossain, A.; Jones, C. The latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1 encodes a product which inhibits cell cycle progression. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 3807–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, D.H. Human cytomegalovirus riding the cell cycle. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 204, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.L.; Cappell, S.D.; Tsai, F.C.; et al. The proliferation-quiescence decision is controlled by a bifurcation in CDK2 activity at mitotic exit. Cell 2013, 155, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Shi, D.; Xing, X.; et al. Coronavirus porcine epidemic diarrhea virus nucleocapsid protein interacts with p53 To Induce cell cycle arrest in S-phase and promotes viral replication. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0018721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Tsurimoto, T.; Juillard, F.; et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA recruits the DNA polymerase clamp loader to mediate efficient replication and virus persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 2014, 111, 11816–11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, R.; Sugiura, T.; Kume, S.; et al. A novel single virus infection system reveals that influenza virus preferentially infects cells in G1 phase. PLoS One 2013, 8, e67011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaplana, L.; Wilson, K.; Redman, E.M.; et al. Pathogen persistence in migratory insects: high levels of vertically-transmitted virus infection in field populations of the African armyworm. Evol. Ecol. 2010, 24, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Coxsackievirus A6 induces cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase for viral production. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Yang, K.; Xiao, W.; et al. Establishment of an insect cell clone that harbours a partial baculoviral genome and is resistant to homologous virus infection. Journal of General Virology 2009, 90(Pt 12), 2871–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, M.L.; Sherlock, G.; Saldanha, A.J.; et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 1977–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Virto, C.; Murillo, R.; et al. Covert infection of insects by baculoviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lin, T.; Pan, L.; et al. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus nucleocapsid assembly is interrupted upon deletion of the 38K gene. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11475–11485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Dong, Z.Q.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV) induces G2/M arrest to promote viral multiplication by depleting BmCDK1. Insects 2021, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Wang, H.; Han, L.; et al. Single-Cell analysis of the impact of host cell heterogeneity on infection with Foot-and-Mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00179–e00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, S.; Miwa, S.; Mii, S.; et al. Cancer cells mimic in vivo spatial-temporal cell-cycle phase distribution and chemosensitivity in 3-dimensional Gelfoam® histoculture but not 2-dimensional culture as visualized with real-time FUCCI imaging. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Qu, J.; Peng, Q.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of EBV-driven cell cycle progression and oncogenesis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Sun, R.; Guo, Q.; et al. A self-perpetuating repressive state of a viral replication protein blocks superinfection by the same virus. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Enden, G.; Wei, W.; et al. Baculovirus transit through insect cell membranes: A mechanistic approach. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 223, 115727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Wei, W.; Xu, P.; et al. The cell cycle phase affects the potential of cells to replicate Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus. Acta Virol. 2012, 56, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yu, Z.H.; Li, X.Q.; et al. Heliocoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus induces Hz-AM1 cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase with accumulation of Cyclin B1. Virus Res. 2004, 105, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yuan, M.; Shakeel, M.; et al. Selection and evaluation of reference genes for expression analysis using qRT-PCR in the beet armyworm Spodoptera exigua (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). PLoS One 2014, 9, e84730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, M.; et al. Human parvovirus B19 utilizes cellular DNA replication machinery for Viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01881–e01817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Cell cycle distribution and differences between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. Se301 and P8-Se 301-C1 cells were seeded in culture dishes, then cells were collected at specific time points, stained with PI, and cell distribution in G1 phase (A), S phase (B), and G2/M phase (C) was determined using flow cytometry. The histogram showed the difference in cell cycle distribution between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells at 0 h of subculture (D). Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells were treated with 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h to synchronize them in the G1 phase (E). Cells were collected at different time points after release incubation with fresh medium. Then flow cytometry was used to analyze the cell cycle progress of Se301 (F) and P8-Se301-C1 (G) cells. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Cell cycle distribution and differences between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. Se301 and P8-Se 301-C1 cells were seeded in culture dishes, then cells were collected at specific time points, stained with PI, and cell distribution in G1 phase (A), S phase (B), and G2/M phase (C) was determined using flow cytometry. The histogram showed the difference in cell cycle distribution between Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells at 0 h of subculture (D). Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells were treated with 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h to synchronize them in the G1 phase (E). Cells were collected at different time points after release incubation with fresh medium. Then flow cytometry was used to analyze the cell cycle progress of Se301 (F) and P8-Se301-C1 (G) cells. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Differential expression of DNA replication-related genes in Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. Cells were treated with hydroxyurea to synchronize in G1 phase and then released for culture. The transcriptional expression levels of BAF (A), PCNA (B), and MCM4 (C) genes in P8-Se301-C1 cells and Se301 cells at different time points after release were detected by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Differential expression of DNA replication-related genes in Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. Cells were treated with hydroxyurea to synchronize in G1 phase and then released for culture. The transcriptional expression levels of BAF (A), PCNA (B), and MCM4 (C) genes in P8-Se301-C1 cells and Se301 cells at different time points after release were detected by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Effect of homologous virus SeMNPV and heterologous virus AcMNPV infection on the cell cycle of Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. The percentage of Se301 cells in different cell cycle phases after SeMNPV (A) or vAcWT (B) infection. The percentage of P8-Se301-C1 cells in different cell cycle phases after SeMNPV (C) or vAcWT (D) infection. Cells were infected with SeMNPV at an MOI of 1 or vAcWT at an MOI of 10. Mock infections were performed by replacing the virus with the medium. The cells were harvested at different time points after infection, and stained with PI, and the distribution of cells in the G1, S, and G2/M phases was analyzed by flow cytometry. V: virus-infected cells, M: mock-infected cells. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Effect of homologous virus SeMNPV and heterologous virus AcMNPV infection on the cell cycle of Se301 and P8-Se301-C1 cells. The percentage of Se301 cells in different cell cycle phases after SeMNPV (A) or vAcWT (B) infection. The percentage of P8-Se301-C1 cells in different cell cycle phases after SeMNPV (C) or vAcWT (D) infection. Cells were infected with SeMNPV at an MOI of 1 or vAcWT at an MOI of 10. Mock infections were performed by replacing the virus with the medium. The cells were harvested at different time points after infection, and stained with PI, and the distribution of cells in the G1, S, and G2/M phases was analyzed by flow cytometry. V: virus-infected cells, M: mock-infected cells. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity of P8-Se301-C1 cells at different cell cycle phases to SeMNPV superinfection. P8-Se301-C1 cells was synchronized in G1 phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h), S phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h and released for 6 h), and G2/M phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h and released for 18 h, and then cultured in medium containing 7 μg/mL nocodazole for 12 h), respectively. After the cells were infected with SeMNPV (MOI=1) at 0 ℃ or 27 ℃, qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the amount of virus adsorbed on the cell surface at 0 h p.i. (A), intracelluar viral DNA replication at 48 h p.i. (B), the BV production of the culture supernatant at indicated time points (C). The unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells were used as control. ns indicates non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity of P8-Se301-C1 cells at different cell cycle phases to SeMNPV superinfection. P8-Se301-C1 cells was synchronized in G1 phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h), S phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h and released for 6 h), and G2/M phase (cultured in medium containing 80 μg/mL hydroxyurea for 20 h and released for 18 h, and then cultured in medium containing 7 μg/mL nocodazole for 12 h), respectively. After the cells were infected with SeMNPV (MOI=1) at 0 ℃ or 27 ℃, qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the amount of virus adsorbed on the cell surface at 0 h p.i. (A), intracelluar viral DNA replication at 48 h p.i. (B), the BV production of the culture supernatant at indicated time points (C). The unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells were used as control. ns indicates non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

SeMNPV superinfection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells induced G2/M phase arrest and downregulated Cyclin B and CDK1 expression. After P8-Se301-C1 cells were infected with SeMNPV, flow cytometry analysis was performed to determine the cell cycle distributions at the indicated time points. Histograms show the percentage of cells in each phase at different times of SeMNPV infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells synchronized to the G1 phase (A), synchronized to the S phase (B), and synchronized to the G2/M phase (C). QRT-PCR analysis was used to determine the transcriptional levels of CyclinB and CDK1 in SeMNPV infected unsynchronized Se301 cells (D), unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells (E), G1 phase (F), S phase (G), and G2/M phase P8-Se301-C1 cells (H). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

SeMNPV superinfection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells induced G2/M phase arrest and downregulated Cyclin B and CDK1 expression. After P8-Se301-C1 cells were infected with SeMNPV, flow cytometry analysis was performed to determine the cell cycle distributions at the indicated time points. Histograms show the percentage of cells in each phase at different times of SeMNPV infection of P8-Se301-C1 cells synchronized to the G1 phase (A), synchronized to the S phase (B), and synchronized to the G2/M phase (C). QRT-PCR analysis was used to determine the transcriptional levels of CyclinB and CDK1 in SeMNPV infected unsynchronized Se301 cells (D), unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells (E), G1 phase (F), S phase (G), and G2/M phase P8-Se301-C1 cells (H). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

G2/M phase arrest is required for SeMNPV replication in P8-Se301-C1 cells. P8-Se301-C1 cells synchronized to G2/M (A) and G1 (B) phases were infected with SeMNPV (MOI = 1) for 1 h and then cultured in a medium containing 7 μg/mL nocodazole to arrest cells in the G2/M phase. QRT-PCR was performed to measure the BV production in the culture supernatant at indicated time points. The infected cells cultured in a medium without nocoodazole were used as the control. (C) Light microscopy of SeMNPV infected P8-Se301-C1 cells at specific cell cycle phases. P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized at G1 phase, S phase and G2/M phase and then were infected with SeMNPV (MOI=1). In addition, SeMNPV-infected G1 and G2/M cells were treated with nocodazole to further arrest the infected cells in the G2/M cells. Unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells were used as control. Bar=50 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

G2/M phase arrest is required for SeMNPV replication in P8-Se301-C1 cells. P8-Se301-C1 cells synchronized to G2/M (A) and G1 (B) phases were infected with SeMNPV (MOI = 1) for 1 h and then cultured in a medium containing 7 μg/mL nocodazole to arrest cells in the G2/M phase. QRT-PCR was performed to measure the BV production in the culture supernatant at indicated time points. The infected cells cultured in a medium without nocoodazole were used as the control. (C) Light microscopy of SeMNPV infected P8-Se301-C1 cells at specific cell cycle phases. P8-Se301-C1 cells were synchronized at G1 phase, S phase and G2/M phase and then were infected with SeMNPV (MOI=1). In addition, SeMNPV-infected G1 and G2/M cells were treated with nocodazole to further arrest the infected cells in the G2/M cells. Unsynchronized P8-Se301-C1 cells were used as control. Bar=50 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation in biological triplicate experiments. ns: no significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

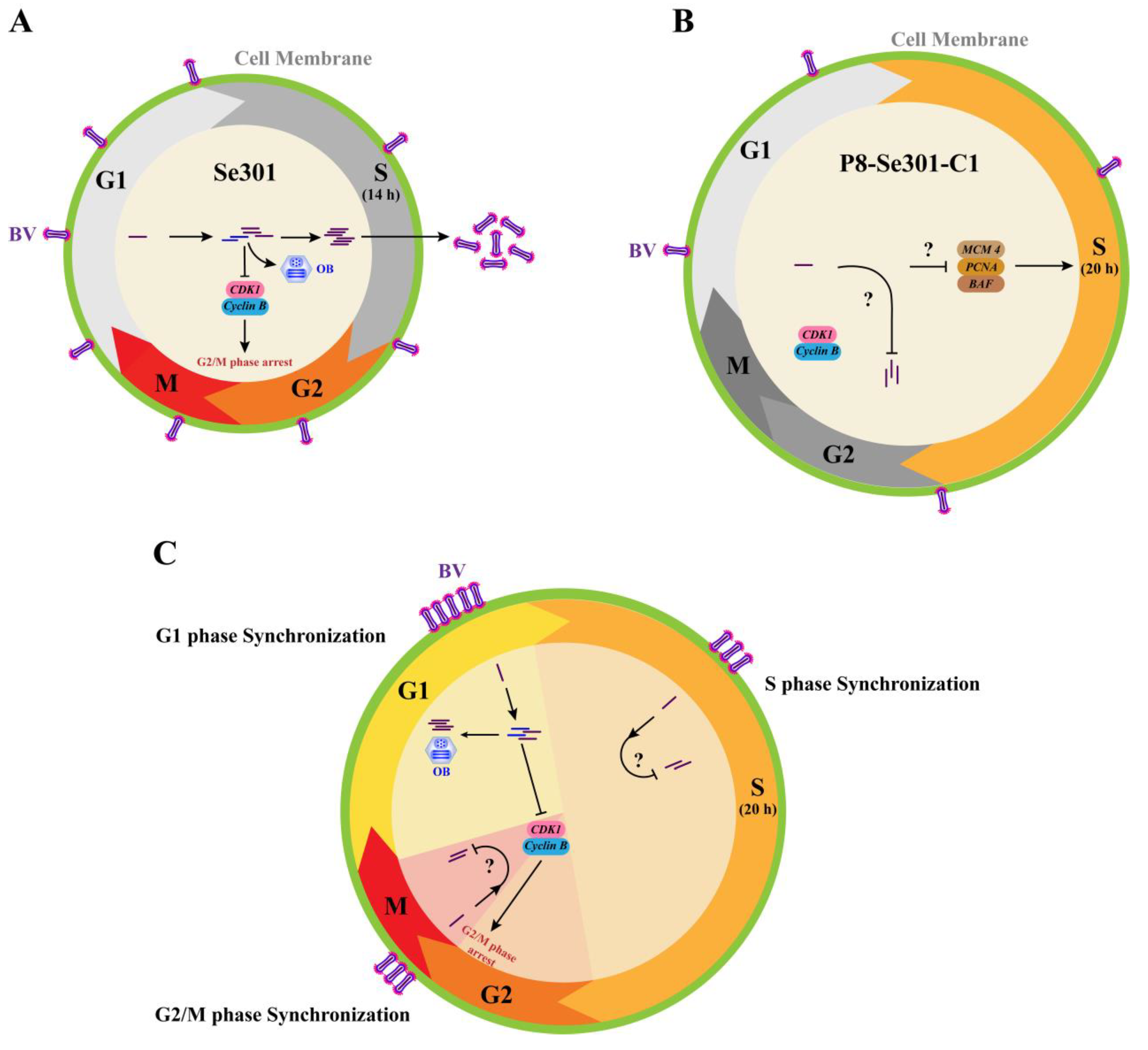

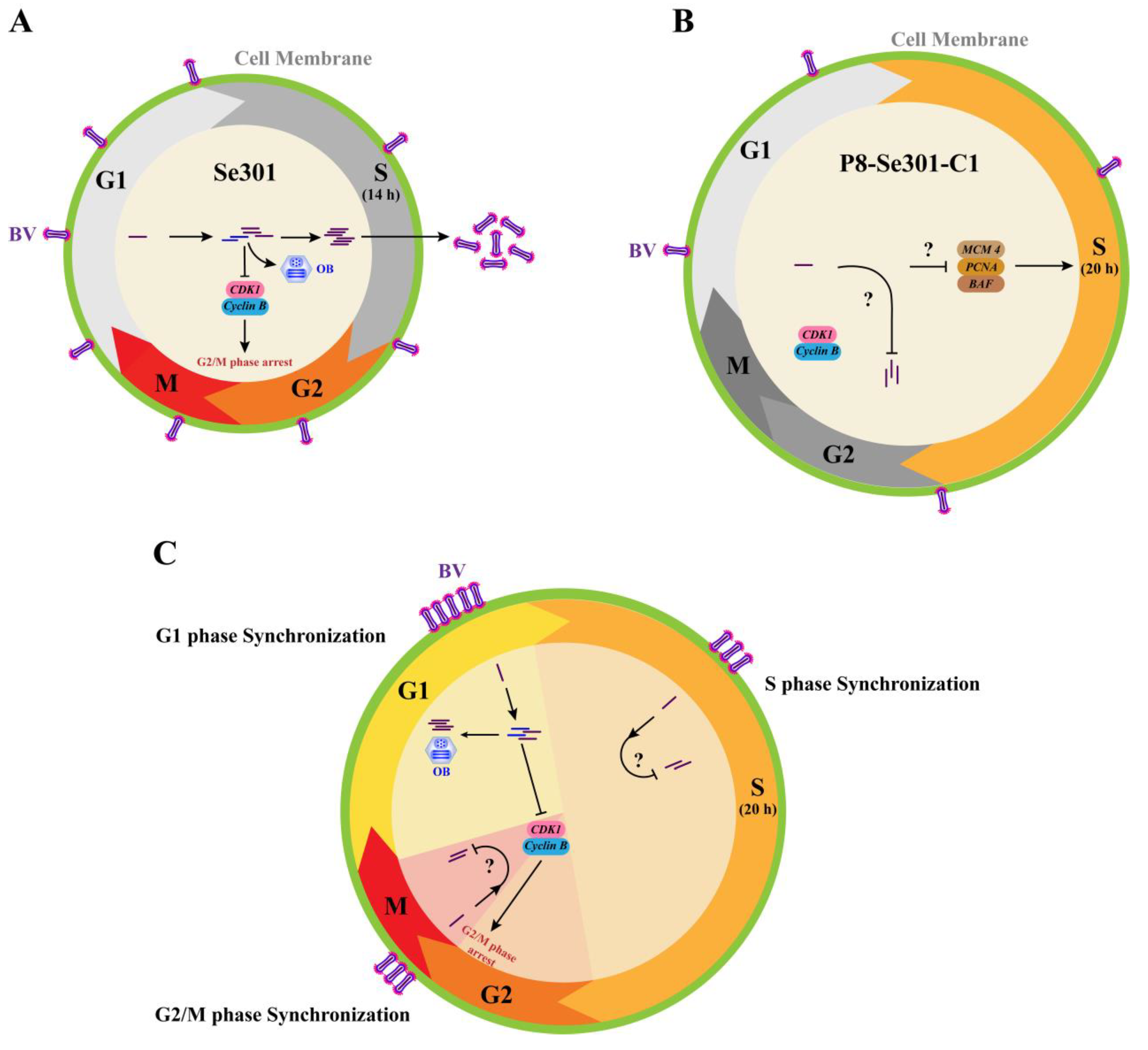

Figure 7.

Schematic of SeMNPV superinfection exclusion alleviation by cell cycle progression regulation in latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells. (A) Cell cycle progression of Se301 cells infected with SeMNPV. SeMNPV infection of Se301 cells downregulated the expression of Cyclin B and CDK1, induced G2/M phase arrest, and produced progeny BVs and ODVs. (B) Regulation of cell cycle progression in P8-Se301-C1 by SeMNPV superinfection. The expression of DNA replication-related genes MCM 4, PCNA, and BAF was downregulated and the S phase was prolonged in P8-Se301-C1 cells. SeMNPV superinfection did not change Cyclin B and CDK1 expression or induce G2/M phase arrest, and viral progeny production was inhibited. (C) SeMNPV infection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells regulated cell cycle progress and partially alleviated SeMNPV superinfection exclusion. SeMNPV superinfection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells promoted viral adsorption on the cell surface and intracellular viral DNA replication, downregulated Cyclin B and CDK1 expression, induced G2/M phase arrest, and increased the production of BVs and OBs. Synchronization of SeMNPV-infected G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells in the G2/M phase further increased the progeny virus production. However, SeMNPV infection of S phase or G2/M phase P8-Se301-C1 cells did not downregulate Cyclin B and CDK1 expression, and the production of progeny BVs and OBs was deduced.

Figure 7.

Schematic of SeMNPV superinfection exclusion alleviation by cell cycle progression regulation in latently infected P8-Se301-C1 cells. (A) Cell cycle progression of Se301 cells infected with SeMNPV. SeMNPV infection of Se301 cells downregulated the expression of Cyclin B and CDK1, induced G2/M phase arrest, and produced progeny BVs and ODVs. (B) Regulation of cell cycle progression in P8-Se301-C1 by SeMNPV superinfection. The expression of DNA replication-related genes MCM 4, PCNA, and BAF was downregulated and the S phase was prolonged in P8-Se301-C1 cells. SeMNPV superinfection did not change Cyclin B and CDK1 expression or induce G2/M phase arrest, and viral progeny production was inhibited. (C) SeMNPV infection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells regulated cell cycle progress and partially alleviated SeMNPV superinfection exclusion. SeMNPV superinfection of G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells promoted viral adsorption on the cell surface and intracellular viral DNA replication, downregulated Cyclin B and CDK1 expression, induced G2/M phase arrest, and increased the production of BVs and OBs. Synchronization of SeMNPV-infected G1 phase P8-Se301-C1 cells in the G2/M phase further increased the progeny virus production. However, SeMNPV infection of S phase or G2/M phase P8-Se301-C1 cells did not downregulate Cyclin B and CDK1 expression, and the production of progeny BVs and OBs was deduced.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).