1. Introduction

There is an increasing need for innovative solutions such as assistive technologies, and eHealth to support the daily lives of older adults [

1] due to the ageing society posing challenges to worldwide healthcare systems [

2]. Moreover, it is expected that older adults will have an increased desire for autonomy, where living longer at home will become more common in our society [

3,

4]. Alongside this, the need for care technologies is strengthened by the COVID-19 pandemic. During this pandemic, care was often delivered over distance by the use of telemedicine [

5].

Care technologies offer a solution to mitigate the global burden of cognitive decline related to ageing [

6]. Additionally, care technologies can support autonomy for older adults, and hence, support in this need of older adults [

3]. Furthermore, independent living at home can be beneficial in making healthcare more resistant to global challenges related to the double-ageing society [

2]. Finally, care technologies such as eHealth devices can support in improving communication between clients, informal caregivers and formal caregivers [

7,

8].

Over the years, various care technologies have been developed, for example: socially assistive robots for companionship or daytime structure [

9], lifestyle monitoring to identify patterns in the lifestyle of older adults and inform about deterioration or alarming situations [

9]. Additionally, many eHealth applications have been developed with various purposes, such as delivering care via screen and over distance or stimulating the cognitive or physical functioning of older adults. To conclude, there is a wide variety of different care technologies that can be embedded into everyday healthcare processes.

However, embedding such innovative care technologies into the care processes of different healthcare systems requires training, knowledge and devotion among healthcare personnel. Furthermore, concepts such as eHealth literacy may play an important role [

10]. The non-adoption that characterized healthcare technologies, as was found by Greenhalgh et al. [

11], was slightly resolved by measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic [

12]. Nevertheless, creating a technology-positive environment is a long-term process [

13]. Hence, it cannot be assumed that the improved adoption of healthcare technologies, related to the COVID-19 pandemic, will remain in the post-pandemic era [

12]. Therefore, it is important to constantly seek for opportunities to improve the acceptance and adoption of care technology.

To date, it is underexplored during which stages of dementia these technologies can be best implemented. First, not all developers have specified for which stage of dementia their technology can best be implemented. However, dementia is a progressive disease and people with dementia (PwD) their needs and abilities differ depending on the stage of dementia they are in [

14]. Moreover, it has been suggested [

15] that it is important to introduce care technologies at the appropriate timing, meaning before the cognitive and adaptive abilities of a person with dementia have declined too much. Allowing PwD time to adopt the care technologies in their daily life when they are still able to interact and or operate with the care technologies. Additionally, it has been suggested that the severity of dementia could negatively affect people’s openness to use new devices [

16].

Second, limited information can be found about when care technologies can best be implemented. Although various papers provide some suggestions into when the tested technologies should be implemented [

17,

18,

19,

20] and companies provide some recommendations on when to implement their technology (e.g., [

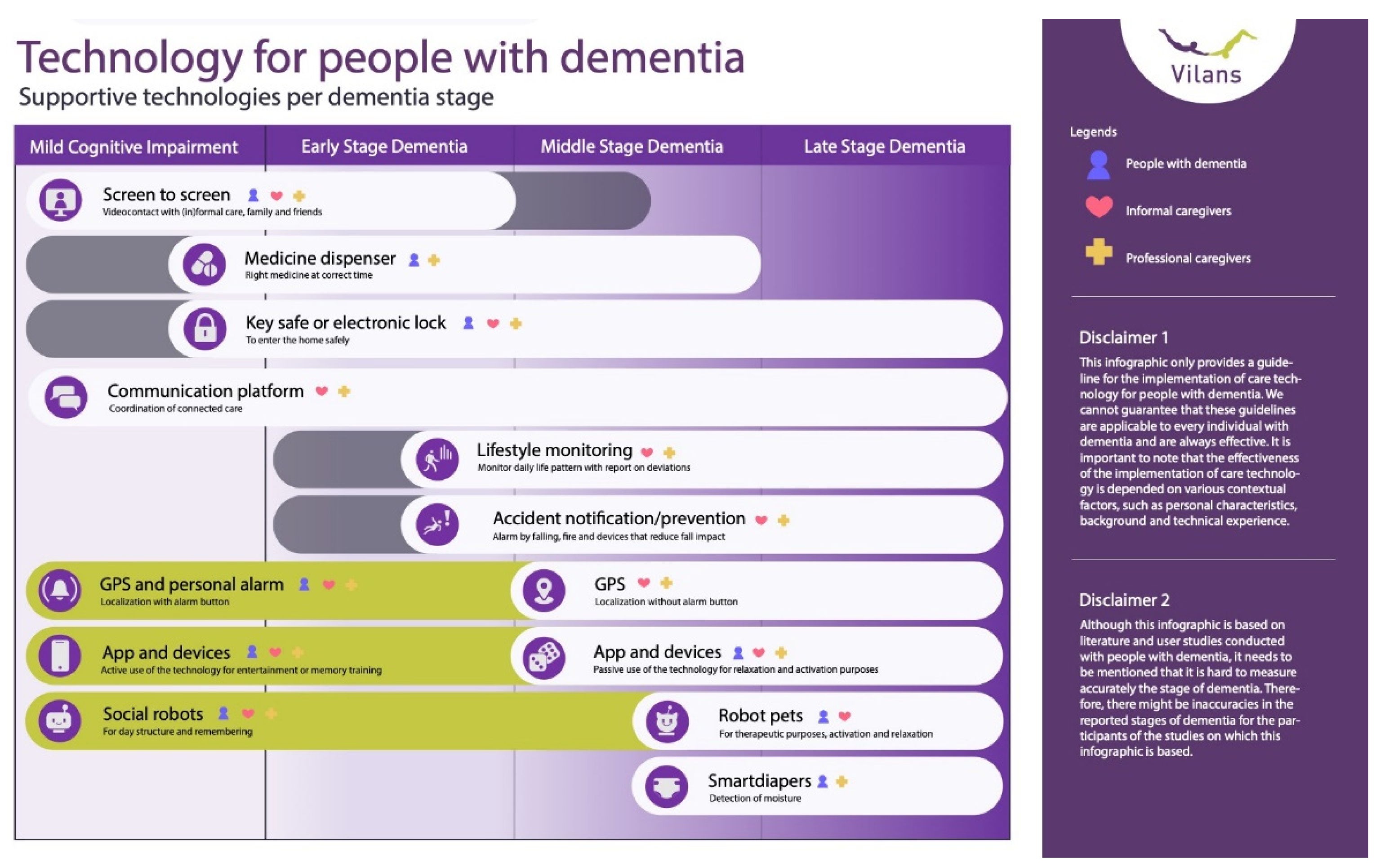

21]), a scan of the literature shows that there are not much explicit guidelines or manuals on this topic. Vilans, the Dutch expertise centre on long-term care (see

Figure 1), which visually represents the appropriate time to implement various care technologies [

22].

Although this infographic seems relevant, the infographic is currently based on the experiences of the authors during various international and national projects. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to improve the infographic developed by Vilans based on findings from the literature (both scientific papers as well as whitepapers) and complemented by interviewing people who have experience with the implementation of care technology in order to reflect on the improved infographic and to further improve it. The improved infographic is intended for healthcare personnel to guide them in effectively implementing various care technologies.

2. Literature Search

2.1. Method

Snowballing was used to find papers, including the use of literature reviews. This search was conducted in 2022. Additionally, google scholar was used as well as the internet to search for whitepapers. The researchers also looked at scales for determining the stages of dementia in order to get insights into the possibilities and conditions per stage of dementia in terms of cognitive decline [

23].

2.2. Insights Gained from the Literature and Changes Made to the Infographic

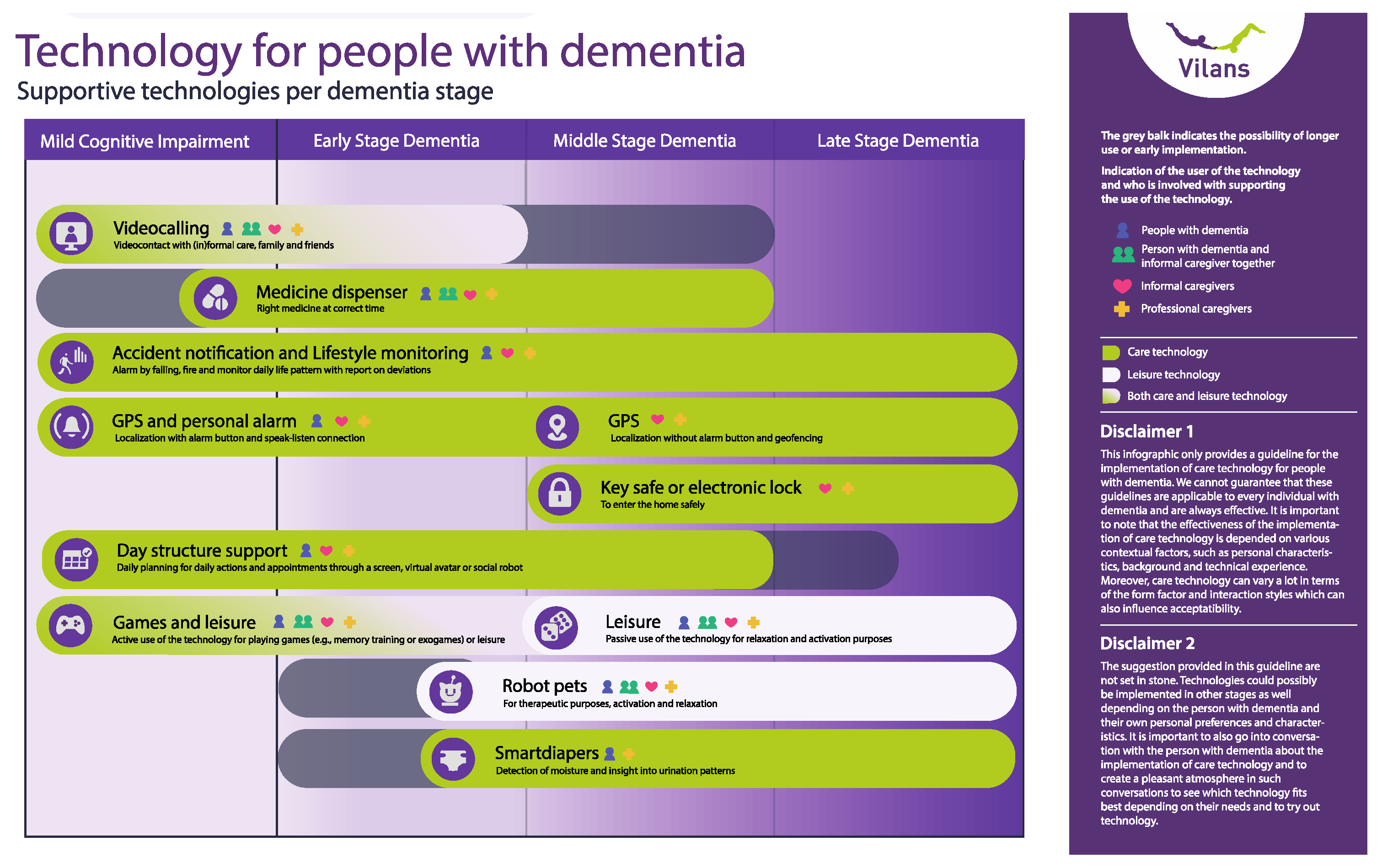

Figure 2.

Revised version of the Infographic for Technology for People with Dementia.

Figure 2.

Revised version of the Infographic for Technology for People with Dementia.

Screen to Screen

Looking at the literature it has been shown that people who have early-stage dementia can still use communication platforms [

24]. Moreover, communication platforms such as video calling which provide care over distance can be effective for people with mild cognitive impairment [

25].

However, it was also suggested that contextual factors such as the received support or ongoing education of PwD can play a role in maximizing the benefit of the technology [

26]. It might be the case that people could use a device longer because of having such a support system. Therefore, in the infographic a grey balk was added for screen to devices till the middle stage of dementia. The use of a grey balk in the infographic is used the indicate the possibility of longer use or early implementation. For screen to screen technology, it is added to show the possible for some PwD to still use this technology at a later stage of dementia.

Medicine Dispenser

Earlier work has shown that medicine dispensers can be operated by people with mild to moderate dementia [

17]. However, it has been found that the alarms and lights of a medicine dispense can cause stress for people who have more severe stages of dementia [

27]. This suggests that for more severe stages of dementia medicine dispensers would not be suitable.

Looking at the GDS scale [

23] for determining the stage of dementia, it is indicated that during the mild stage of dementia the decease effects mostly the activities of daily living, which also includes medicine intake. Suggesting the relevance for medicine dispensers during this stage of dementia.

In line with this the Alzheimer society [

28] explained that during the early stages of dementia (GDS2) people struggle with memory problems. Therefore, also in these early stages medicine dispensers could be of relevance in supporting PwD with their medicine intake. Moreover, as it has been advised to implement new technology at an early stage of the disease [

29] a grey balk was placed suggesting the possibility to implement a medicine dispenser for people with a mild cognitive impairment.

Key Safe or Electronic Lock

Previous work has suggested that access systems/installations are most suitable during the middle stage of dementia [

18,

30]. Moreover, in line with the implementation advise to introduce care technology early on [

29] it might be valuable to introduce key saves and electronic locks early on in the dementia process to enhance acceptance of having such a technology at home. Even though PwD do not need to interact with the technology, it could allow them to get used to the placement of the technology. Possibly, they might be more acceptive of having such technology around them. Therefore, a grey balk was placed during the MCI stage.

Lifestyle Monitoring

Looking at the literature it was suggested to implement lifestyle monitoring at an early stage [

19,

20]. Informal caregivers and case managers suggested that decline of the health could be detected by the technology during the early phase of dementia, and that through this information the care could be adjusted accordingly [

34]. Therefore, the technology could be used preventively to detect health problems and quickly act on the problems [

35]. Furthermore, it was suggested that lifestyle monitoring could be valuable for people with mild to severe stages of dementia. In these stages of dementia PwD can often not use active personal alarms anymore [

36]. Lifestyle monitoring could than detect critical situations without a person with dementia having to activate an alarm [

20]. Alongside this, during the moderate and severe stages of dementia (GDS 6 and 7) sleep patterns change and PwD have their own routine (regardless of time) [

28]. For these stages of dementia lifestyle monitoring could also be of value to keep track of PwD’ daily rhythm and activities.

Accident Notification

It has been suggested [

37] that safety interventions are often implemented when an accident has already happened. Therefore, being often implemented too late [

37]. Moreover, it has been proposed that early implementation of technology can provide a person with dementia enough time to get used to a new technology and allowing them enough time to incorporate the technology in their everyday routines [

38,

39]

GPS

The Alzheimer society indicated that poor orientation could occur during the early stages of dementia [

28]. Therefore, the use of a GPS tracker could be relevant during this stage. This is confirmed by the findings from the literature, suggesting early implementation of a GPS tracker and thereby facilitating more freedom for PwD [

40,

41] as well as decreasing stress and anxiety [

42]. Moreover, it was explained that an early implementation of a GPS tracker could provide more time for PwD to accept the technology and become more confident with using the technology [

43].

Moreover, from the literature it was derived that there should be a division between GPS trackers with and without an alarm [

44]. It was suggested that because of the increasing impact of the decease on a person, they could slowly change from an active user, meaning from someone who interacts with the GPS tracker to a passive user: someone who only wears/takes the GPS tracker with them [

44]. As the disease progresses PwD will have more difficulties to understand the buttons present on the GPS tracker and might forgot to press the alarm button [

45] or accidentally press the alarm button. Resulting in a too many alarms for caregivers [

44].

Apps and Devices

The review of the literature showed that there were two types of apps and devices. Those that require an active interaction of a person with dementia (meaning them needing to operate a user interface, for example, for memory training [

46]and devices where a person with dementia interacts in a more passive way with the user interface (e.g., by just holding a pillow or set of balls which than provide sensory output to the person with dementia [

47]. Moreover, it has been suggested that for different stages of dementia different types of simulations are preferred. For people with mild or moderate stages of dementia there is a preference for more challenging tasks (e.g., memory games or video games) [

48]. People with more severe stages of dementia have a preference for more static and sensory focused activities (e.g., listening to music or watching video) [

48].

When looking at the more active interaction technologies, past research has suggested that touchscreen technology (e.g., tablets), can be of value for people who suffer from mild dementia, taking into account that they might need to have support when learning how to operate a touchscreen (e.g., family or formal caregivers) [

26,

49,

50]. Previous work has suggested that active support by carers is important in order to maximize the effectiveness of care technology [

51,

52].

Moreover, prior experience could influence people’s ability to operate a touchscreen, research has shown that some people who were not familiar with using apps or a tablet before the onset of dementia, struggled with learning how to use the technology [

49]. Moreover, it was suggested to introduce new technology before the onset of dementia, to allow them to get familiar with the technology and get used to it [

29]. However, it has been found that people with mid dementia are able to learn how to use a mobile phone, when giving the appropriate training [

53].

Additionally, it has been suggested that apps (e.g., reminding apps or memory training) could also be useful for people with mild to moderate stage dementia [

54,

55] as well as MHealth application for mild to severe stages of dementia [

16].

Social Robots

Research has shown that social robots could be of benefit during the early stages of dementia [

56] as well as the middle and more severe stages of dementia, however findings were mixed [

57]. Moreover, it has been found social robots could cause PwD to get overstimulated or anxious during the later stages of dementia [

58].

Robot Pets

When looking at the implementation of robot pets the literature provides mixed responses. Several studies showed the effectiveness of robot pets for mild/moderate/severe stages of dementia [

59,

60]. However, overall, studies that compare the effectiveness of social robots over various stages of dementia suggest that robot pets are most beneficial for later stages of dementia [

61,

62]. Moreover, past studies have shown positive responses towards the use of robot pets during these moderate to severe stages of dementia [

63,

64,

65].

Smart Diapers

From the review not much could be found regarding the most suitable time to implement smart diapers. Looking at the different stages of dementia and the resulting health consequences [

28] it becomes clear that during the more severe stages of dementia people could become incontinent, having reduced control over their bladder and bowels. Therefore, it seems that smart diapers are most suitable during these stages of dementia.

3. Expert Interviews

3.1. Participants

Five participants, comprising two females and three males, were recruited for the interviews via the warm network of Vilans. Each particpant did have expertise in the implementation of care technology for people with dementia. Their profession, and therefore their specific perspectives and experiences were divers. The professions ranged from researchers, advisors and innovation managers to one participant who had previously worked as a care professional.

3.2. Study Protocol

For the first part of the interview, the interviewers showed the infographic in its current form at the time and the goal of the infographic was stated. The participants all had some level of familiarity with this version of the infographic. They were requested to provide their feedback on the entire infographic, covering their overall impressions as well as specifics such as textual and visual remarks. In the following part of the session, the participants assumed a more active role, as they were requested to design their own infographic, based on their insights and experiences with implementation of digital solutions for people with dementia. They had access to an online Mural board. The Mural board was used as a visualization and brainstorm tool for this part of the session. It had some priorly made materials on display, such as images of care technologies, symbols and tables. The participants could use these materials, or add other items that gave shape to their ideas on a care tech infographic. It was stressed to participants that they were free to decide which technology was most suitable for which stage of dementia. Additionally, participants were asked to use post-it to elaborate on their choices.

For the second part of the interview participants were asked to compare their infographics with the revised infographic from Vilans. Participants were asked about their first impression and were asked to use post it’s to indicate which aspects of the infographics they agreed or disagreed and why. Lastly it was asked if and how the infographics could support in the care for people with dementia.

3.3. Data Analysis

The interviews were directly transcribed using the build-in recording functionality of Microsoft teams. Extensive notes were made alongside the transcripts and Mural post-its. The responses collected during the interviews were summarized using an iterative inductive coding process. The decision was made to derive the suggestions for changes from the data, rather than the themes, as the intention was to improve the mapping of care technologies. A summary of the main suggestions for change in the infographic is included.

3.4. Revision on the Infographic

For several participants, there was confusion about the labeling of de infographic, for example, it was indicated that the label apps and devices were too broad, or it was suggested that some devices could be merged. For example, lifestyle monitoring and accident notification which often are included in the same technology or the use of social robots for day time structure. Therefore, the labels were adjusted, and the sentences below were used to describe more clearly wat the AT activities could contain. Moreover, where applicable the devices were merged.

Participants also indicated some ambiguity about the symbols and colors used, for example, the meaning of the elongated grey bars. Moreover, it was indicated that the categories of users of AT, missed one particular category, namely the mutual use of a AT by a person with dementia and an informal caregiver. Therefore, these were all added.

Another suggestion was the distinction between AT focused on the improvement of care and health and leisure technology. It was indicated that this was currently not explicitly mentioned or visualized in the infographic. Therefore, in the revised infographic different colors were used to represent these two types of AT.

For some AT (e.g., medicine dispenser) it was suggested that PwD possibly could use it till a longer stage of dementia while for some other technologies (e.g., smart diapers) it was indicated that early implementation could be possible, these suggestions were also incorporated in the infographic.

Lastly, regarding the disclaimer it was suggested to also acknowledge that the presented guidelines are not set-in stone and that technologies could also be used in other stages of dementia currently not indicated. It was explained that it was most important to look at the person with dementia and their characteristics, background and technology experience when determining which technology is best suited. Moreover, it is important to go into conversation with the person with dementia when deciding which technology to implement.

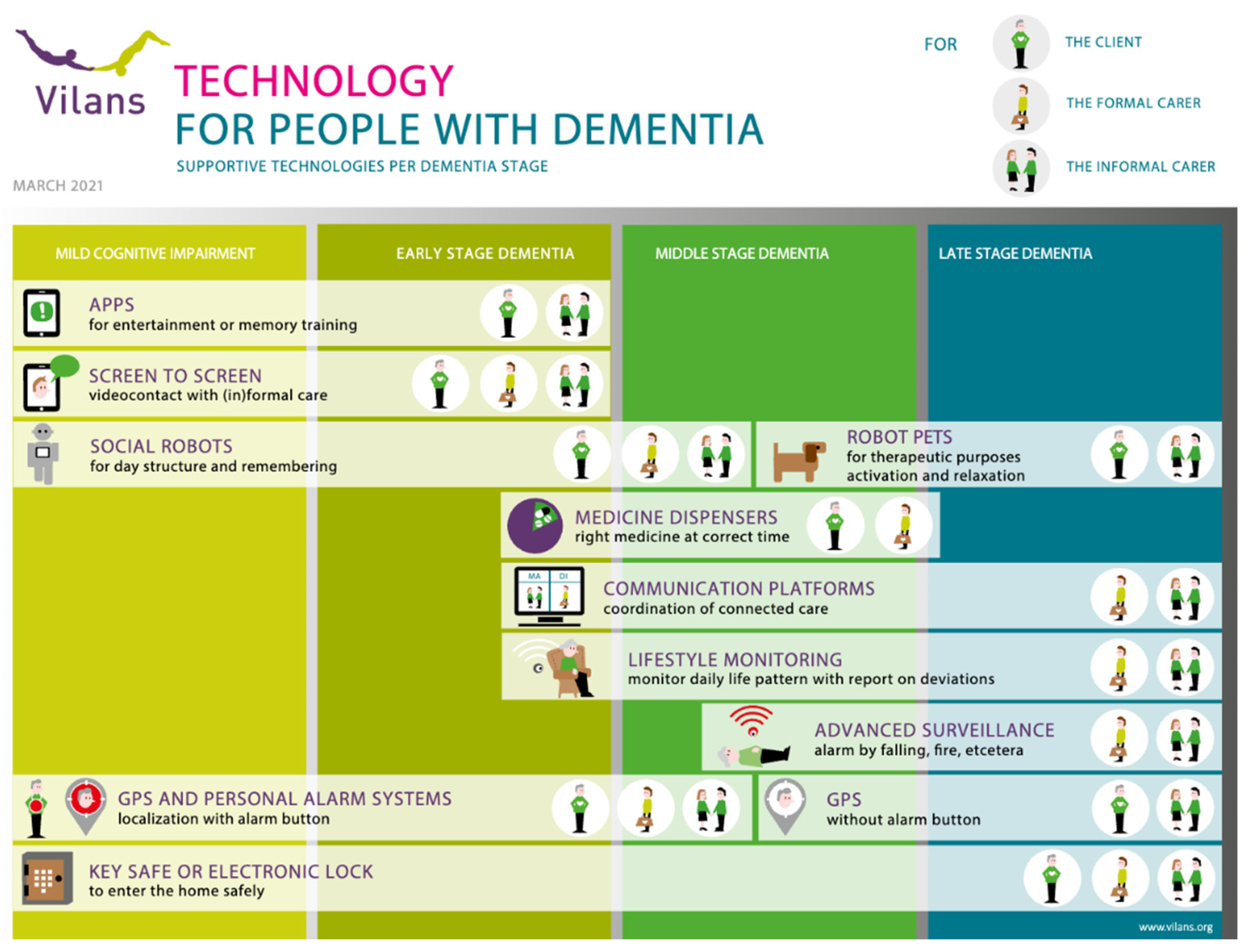

Figure 3.

Final version of the Infographic for Technology for People with Dementia.

Figure 3.

Final version of the Infographic for Technology for People with Dementia.

3. Discussion

Van der Leeuw et al., [

22]. have made an infographic advising healthcare providers at which phase of dementia which care technology could be used. Such infographics might be valuable in order to foster the digital transition in healthcare. Care technologies face difficulties with their implementation [

10], and striving for an eHealth positive environment is a long-term process [

12]. Therefore, infographics might be helpful for healthcare organizations to better align the implementation of care technologies with the needs of clients and healthcare personnel. Hence, in the current article, we have updated the infographic based on the findings of a literature review and expert interviews. Several adaptations have been made to the infographic. The first adaptation involves earlier implementation of various care technologies, such as lifestyle monitoring and medicine dispensers [

12,

20]. Such technology could already be of value for people in the earlier stages of dementia [

19,

20]. Moreover, it is recommended to introduce PwD to care technology before the onset of dementia, as this allows them to get familiar with the technology before or during the early signs of the disease [

66,

67].

The literature search also showed that the effectiveness and acceptance of care technology for PwD can be dependent on various contextual factors, such as the support received by friends or family members and experience with the use of technology in general [

49]. This was not yet incorporated in the previous infographic [

22]. Moreover, during the interviews, it also became apparent that some people (even though a small group) are able to continue using technology during a later stage of dementia (e.g., touchscreen devices). A finding that was not in line with the results of the literature review. This suggests the importance of also taking personal differences into account between PwD, such as personal characteristics and contexts when introducing technology to PwD.

Therefore, it is important to consider the proposed results as guidelines and not targeted solutions, due to large differences between PwD and their syndromes. As a result, a specific situation could require one to differ from the proposed guidelines. Nevertheless, this infographic provides valuable insight that can support the implementation process of healthcare technology.

Lastly, from the interviews it became apparent that there was also a need for having an infographic or visual that shows the available care technologies based on the needs and goals of a person with dementia. Meaning, a different type of framing, where one does not look purely at the stage of dementia but rather puts the person with dementia central as well as their needs and goals in life. Visualizing from that perspective what is available in terms of technology. Therefore, it would be valuable for future work to create such an infographic, for example in co-creation with PwD and informal and formal caregivers.

4. Conclusion

Results of this work highlight the importance of considering that the effectiveness of the implementation of care technology depends on various contextual factors, such as personal characteristics, background and technical experience. Nevertheless, this infographic holds important value in facilitating the digital transition for healthcare institutions and personnel by offering insights into the implementation process of healthcare technology. It is essential to deploy care technologies at the right timing and dementia stage, and as such, this infographic can serve as a valuable support resource for healthcare professionals.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.I.A., D.V. and H.H.N.; validation, S.I.A., D.V. and P.K..; formal analysis, S.I.A. and D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.A., B.H. and D.V. Writing—review and editing, H.H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

There was no need to obtain an institutional review board statement as this work was a review.

Informed Consent Statement

Oral consent from participants, since the participants cannot be identified.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the care professionals who participated in the interviews. The research was initiated and financed by Vilans, Centre of Expertise centre for Long-term Term Care, located in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Assistive technology. 2023.

- WHO. Ageing and health. 2022.

- Rogers, W.A.; Mitzner, T.L. Envisioning the future for older adults: Autonomy, health, well-being, and social connectedness with technology support. Futures 2017, 87, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Zmora, R.; Peterson, C.M.; Mitchell, L.L.; Jutkowitz, E.; Duval, S. What interventions keep older people out of nursing homes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3609–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutai, J.W.; Tuazon, J.R. The role of assistive technology in addressing social isolation, loneliness and health inequities among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ienca, M.; Fabrice, J.; Elger, B.; Caon, M.; Pappagallo, A.S.; Kressig, R.W.; Wangmo, T. Intelligent Assistive Technology for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 56, 1301–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Lorig, K.; Holman, H.; Grumbach, K. Patient Self-management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA 2002, 288, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haes, H. Dilemmas in patient centeredness and shared decision making: A case for vulnerability. Patient Educ Couns. 2006, 62, 291–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nap, H.; Buimer, H.; Wouters, E. Value-based eHealth: Lifestyle monitoring. Gerontechnology 2020, 19, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A'Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med Internet Res. 2017, 19, e367–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getson, C.; Nejat, G. The adoption of socially assistive robots for long-term care: During COVID-19 and in a post-pandemic society. Heal. Manag. Forum 2022, 35, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, T.; Leppälahti, T.; Porokuokka, J.; Heikkinen, S. Impacts of a Care Robotics Project on Finnish Home Care Workers’ Attitudes towards Robots. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienca, M.; Fabrice, J.; Elger, B.; Caon, M.; Pappagallo, A.S.; Kressig, R.W.; Wangmo, T. Intelligent Assistive Technology for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 56, 1301–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holthe, T.; Jentoft, R.; Arntzen, C.; Thorsen, K. Benefits and burdens: family caregivers’ experiences of assistive technology (AT) in everyday life with persons with young-onset dementia (YOD). Disabil. Rehabilitation: Assist. Technol. 2017, 13, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, K.; Mehmood, Z.; Awan, I.A.; Saba, T.; Alharbey, R.; Qadah, T.; Alrige, M.A. A comprehensive study of mobile-health based assistive technology for the healthcare of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Heal. Care Manag. Sci. 2019, 23, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriks, S.; Reinersmann, A.; van der Roest, H.G.; Meiland FJM, Davies, R.J.; Moelaert, F.; et al. Review of ICT-based services for identified unmet needs in people with dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2007, 6, 223–46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, N.A.; Azad-Khaneghah, P.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Liu, L. What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review. Alzheimer's Dementia: Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2018, 10, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee-Cheong, S.; Amanullah, S.; Jardine, M. New assistive technologies in dementia and mild cognitive impairment care: A PubMed review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 73, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nap, H.H.; Lukkien, D.; Cornelisse, L.; van der Weegen, S.; van der Leeuw, J.; van der Sande, R. Whitepaper Leefstijlmonitoring. 2017.

- van Rooij, T. “Dit is nog makkelijker”, Herken bij welke zorgvraag jij je cliënt kan ondersteunen met Tessa. 2021.

- van der Leeuw, J.; Cornelisse, C.C. L, Suijkerbuijk, S.; Herman Nap, H. Infographic Technology for People with Dementia.

- Reisberg, B.; Ferris, S.H.; De Leon, M.J.; Crook, T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E.; Magnusson, L.; Arvidsson, H.; Claesson, A.; Keady, J.; Nolan, M. Working together with persons with early stage dementia and their family members to design a user-friendly technology-based support service. Dementia 2007, 6, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, P.; Hui, E.; Dai, D.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E.; Magnusson, L.; Arvidsson, H.; Claesson, A.; Keady, J.; Nolan, M. Working together with persons with early stage dementia and their family members to design a user-friendly technology-based support service. Dementia 2007, 6, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svagård, I.S.; Boysen, E.S. Electronic Medication Dispensers Finding the Right Users – A Pilot Study in a Norwegian Municipality Home Care Service. In 2016. p. 281–4.

- Alzheimer’s Society. The progression and stages of dementia. 2020.

- Lim, F.S.; Wallace, T.; Luszcz, M.A.; Reynolds, K.J. Usability of Tablet Computers by People with Early-Stage Dementia. Gerontology 2012, 59, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perälä, S.; Mäkelä, K.; Salmenaho, A.; Latvala, R. Technology for Elderly with Memory Impairment and Wandering Risk. E-Health Telecommun. Syst. Networks 2013, 02, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Naveira, L.; Alonso-Búa, B.; de Labra, C.; Gregersen, R.; Maibom, K.; Mojs, E.; Krawczyk-Wasielewska, A.; Millán-Calenti, J.C. UnderstAID, an ICT Platform to Help Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boessen, A.B.C.G.; Verwey, R.; Duymelinck, S.; Van Rossum, E. An Online Platform to Support the Network of Caregivers of People with Dementia. J. Aging Res. 2017, 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verwey, R.; Van Berlo, M.; Duymelinck, S.; Willard, S.; Van Rossum, E. Development of an Online Platform to Support the Network of Caregivers of People with Dementia. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016, 225, 567–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zwierenberg, E.; Nap, H.; Lukkien, D.; Cornelisse, L.; Finnema, E.; Dijkstra, A.; Hagedoorn, M.; Sanderman, R. A lifestyle monitoring system to support (in)formal caregivers of people with dementia: Analysis of users need, benefits, and concerns. Gerontechnology 2018, 17, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Leeuw, J.; Jacobs, E. Leefstijlmonitoring in de dagelijkse praktijk. 2021.

- Stokke, R. The Personal Emergency Response System as a Technology Innovation in Primary Health Care Services: An Integrative Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2016, 18, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lach, H.W.; Chang, Y.-P. Caregiver Perspectives on Safety in Home Dementia Care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 29, 993–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pynoos, J.; Ohta, R.J. In-Home Interventions for Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Caregivers. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 1991, 9, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, G.; Johnston, D.; Black, B.S.; Morrison, A.; Rosenblatt, A.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Samus, Q.M. Association of the Spatial Layout of the Home and ADL Abilities Among Older Adults With Dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Other Dementiasr 2011, 26, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pot, A.M.; Willemse, B.M.; Horjus, S. A pilot study on the use of tracking technology: Feasibility, acceptability, and benefits for people in early stages of dementia and their informal caregivers. Aging Ment. Heal. 2011, 16, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Boekel, L.C.; Wouters, E.J.; Grimberg, B.M.; van der Meer, N.J.; Luijkx, K.G. Perspectives of Stakeholders on Technology Use in the Care of Community-Living Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn, M.; Richardson, M.X.; Stridsberg, S.L.; Redekop, K.; Wamala-Andersson, S. Mobile Safety Alarms Based on GPS Technology in the Care of Older Adults: Systematic Review of Evidence Based on a General Evidence Framework for Digital Health Technologies. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- derud, T.; Landmark, B.; Eriksen, S.; Fossberg, A.B.; Brørs, K.F.; Mandal, T.B.; et al. Exploring the use of GPS for locating persons with dementia. Assist technol Res Ser. 2013, 33, 776–783. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Y.; Holbø, K. Value biases of sensor-based assistive technology. In: Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference on - DIS ’12. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press; 2012. p. 572.

- Olsson, A.; Engström, M.; Skovdahl, K.; Lampic, C. My, your and our needs for safety and security: relatives’ reflections on using information and communication technology in dementia care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2011, 26, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, K.; Mehmood, Z.; Saba, T.; Rehman, A.; Munshi, A.M.; Alharbey, R.; Rashid, M. Mobile-Health Applications for the Efficient Delivery of Health Care Facility to People with Dementia (PwD) and Support to Their Carers: A Survey. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M.; Brankaert, R.; Dhaeze, E.; Kenning, G.; Bongers, I.; Eggen, B. Enriching Everyday Lived Experiences in Dementia Care. In: Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. New York,, N.Y.; USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1–13.

- Pappadà, A.; Chattat, R.; Chirico, I.; Valente, M.; Ottoboni, G. Assistive Technologies in Dementia Care: An Updated Analysis of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, Y.; Bergsma, A.; Graff, M.; Dröes, R. Selecting apps for people with mild dementia: Identifying user requirements for apps enabling meaningful activities and self-management. . J. Rehabilitation Assist. Technol. Eng. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewoud, J.H.; de Lange, J. Evaluatie van individuele happy games op de iPad voor mensen met dementie. 2014.

- Orpwood, R.; Bjørneby, S.; Hagen, I.; Mäki, O.; Faulkner, R.; Topo, P. User Involvement in Dementia Product Development. Dementia 2004, 3, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørneby, S.; Topo, P.; Cahill, S.; Begley, E.; Jones, K.; Hagen, I.; Macijauskiene, J.; Holthe, T. Ethical Considerations in the ENABLE Project. Dementia 2004, 3, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, L.; Wilson, B.A.; Carter, G.; Breen, K.; Gosses, A.; Hodges, J.R. Intervening with Everyday Memory Problems in Dementia of Alzheimer Type: An Errorless Learning Approach. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2000, 22, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliard, J.; Hagen, I. Enabling Technologies for People with Dementia: Cross-national analysis report. Enable; 2004.

- Hofmann, M.; Hock, C.; Kühler, A.; Müller-Spahn, F. Interactive computer-based cognitive training in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1996, 30, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, M.; Ahn, H.S.; MacDonald, B.; Liang, A.; Peri, K.; Kerse, N.; Broadbent, E. Homecare Robots to Improve Health and Well-Being in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Early Stage Dementia: Results From a Scoping Study. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 1099.e1–1099e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, J.; Ballhausen, N.; Hering, A.; Kliegel, M.; Beer, T.; Meyer, G. Social Robot Interventions for People with Dementia: A Systematic Review on Effects and Quality of Reporting. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2021, 79, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.S. ADL assistive robot for older adults with dementia. 2017.

- Jøranson, N.; Pedersen, I.; Rokstad, A.M.M.; Ihlebæk, C. Effects on Symptoms of Agitation and Depression in Persons With Dementia Participating in Robot-Assisted Activity: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, M.V.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.; Rodríguez, J.O.; Rebolledo, C.M.; Muñoz, A.P.; Pérez, I.R.; Ruiz, E.O.; Sánchez, A.B.; Cano, V.H.; Chillón, L.C.; et al. Social robots in advanced dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, I.; du Toit, S.H.J.; Lovarini, M. The use of technology to promote meaningful engagement for adults with dementia in residential aged care: a scoping review. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 32, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, V.; De Ronchi, D.; La Ferla, T.; Moretti, F.; Tonelli, L.; Ferrari, B.; Forlani, M.; Atti, A. Animal-assisted interventions for elderly patients affected by dementia or psychiatric disorders: A review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Cooke, M.; Beattie, E.; Jones, C.; Klein, B.; Cook, G.; Gray, C. Exploring the Effect of Companion Robots on Emotional Expression in Older Adults with Dementia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2013, 39, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, T.; Yonemitsu, S.; Itoh, A.; Oikawa, D.; Kawakami, A.; Higashi, Y.; et al. Is an Entertainment Robot Useful in the Care of Elderly People With Severe Dementia? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004, 59, M83–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayashi, K.; Kodate, N.; Masuyama, S. Measuring the impact of age, gender and dementia on communication-robot interventions in residential care homes. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020, 20, 373–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, A.; Hurtienne, J.; Göllner, S.; Langdon, P.; Clarkson, P. Technology supporting the everyday life of people with dementia. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Inclusive Design and Communications – The Role of Inclusive Design in Making Social Innovation Happen. London; 2011. p. 318-327.

- Lindenberger, U.; Lövdén, M.; Schellenbach, M.; Li, S.-C.; Krüger, A. Psychological Principles of Successful Aging Technologies: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2008, 54, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).