Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. AI Agents and the Gender of Agents

2.2. Brand Concept

2.3. AI Agent Trust and Grounding

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Stimulus Development and Measures

3.3. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

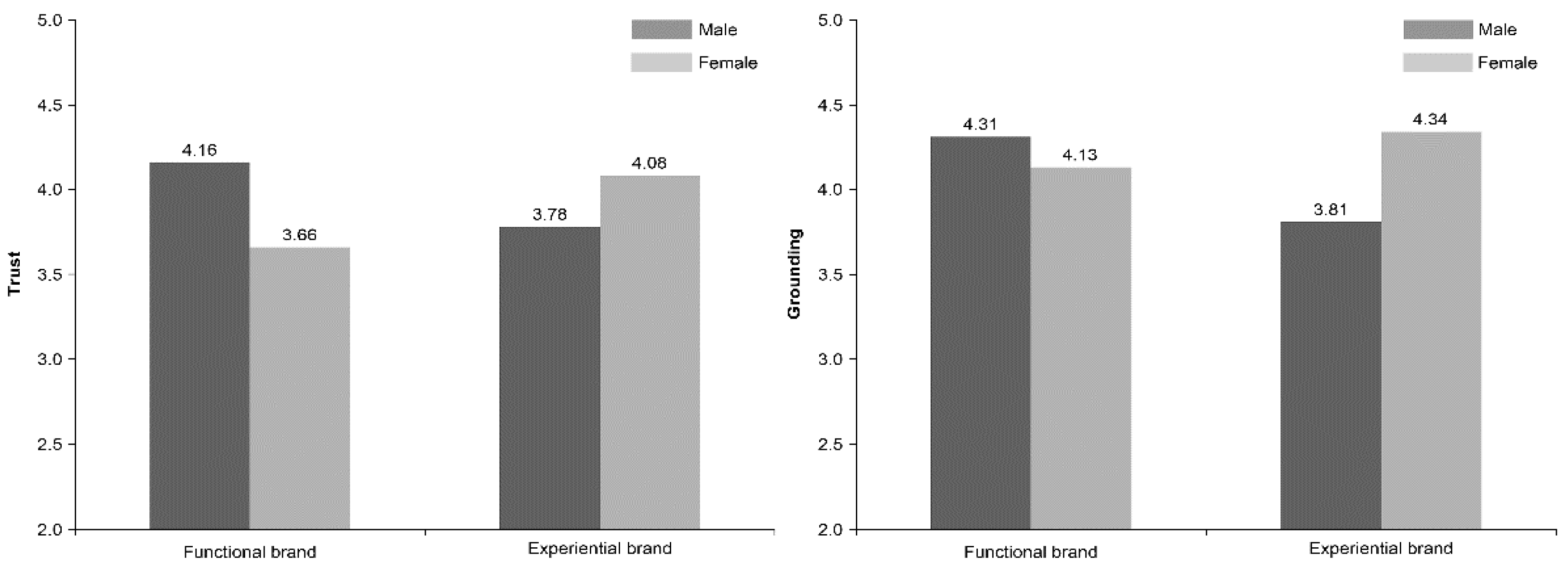

4.2. Analysis of Trust and Grounding

| Dependent Variable | Type Ⅲ Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | Trust | 29.708a | 4 | 7.427 | 7.588 | .000 |

| Grounding | 19.125b | 4 | 4.781 | 3.827 | .005 | |

| Intercept | Trust | 65.061 | 1 | 65.061 | 66.474 | .000 |

| Grounding | 101.102 | 1 | 101.102 | 80.932 | .000 | |

| attitude | Trust | 21.548 | 1 | 21.548 | 22.015 | .000 |

| Grounding | 11.162 | 1 | 11.162 | 8.935 | .003 | |

| Brand Concept(A) | Trust | 1.708 | 1 | 1.708 | 1.745 | .188 |

| Grounding | .007 | 1 | .007 | .005 | .941 | |

| Gender of AI Agent(B) | Trust | 1.819 | 1 | 1.819 | 1.859 | .174 |

| Grounding | .435 | 1 | .435 | .348 | .556 | |

| A X B | Trust | 7.461 | 1 | 7.461 | 7.623 | .006 |

| Grounding | 5.740 | 1 | 5.740 | 4.595 | .033 | |

| Error | Trust | 178.133 | 182 | .979 | ||

| Grounding | 227.359 | 182 | 1.249 | |||

| Total | Trust | 3088.889 | 187 | |||

| Grounding | 3469.444 | 187 | ||||

| Corrected Total | Trust | 207.841 | 186 | |||

| Grounding | 246.485 | 186 | ||||

| Note: R2 = .419 (adjusted R2 = .385). | ||||||

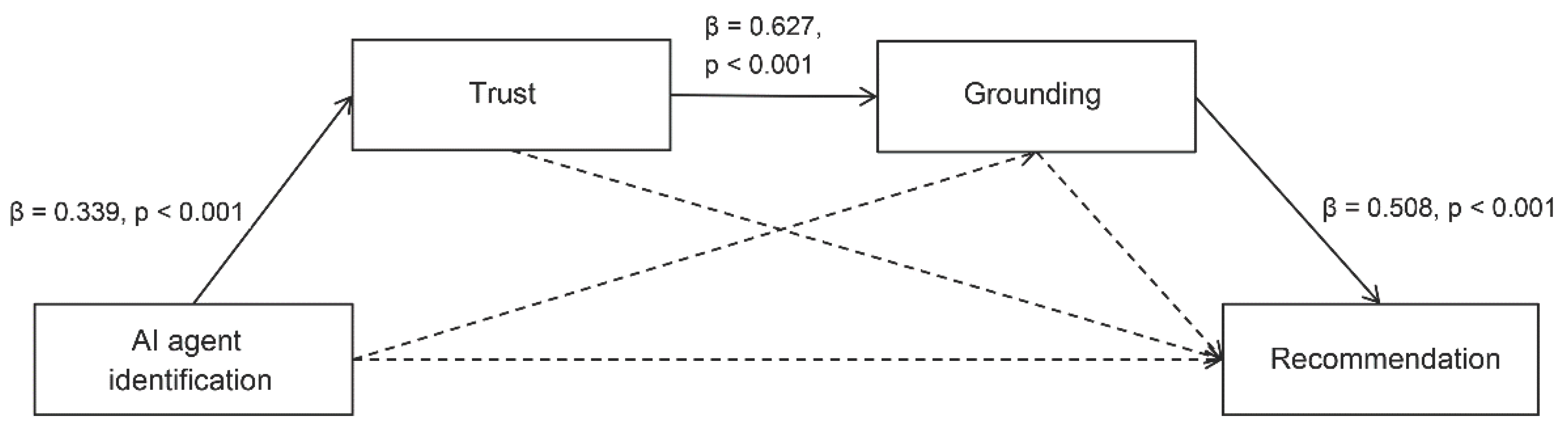

4.3. Mediation Effect

| Outcome variable: Trust | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | Standardized coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Identification | .3002 | .3397 | .0611 | 4.9119 | .000 | .1796 | .4208 |

| Outcome variable: Grounding | |||||||

| Coeff | Standardized coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Identification | .0494 | .0513 | .0576 | .8577 | .3922 | −.0642 | .1629 |

| Trust | .6830 | .6272 | .0651 | 10.4872 | .000 | .5545 | .8115 |

| Outcome variable: Recommendation | |||||||

| Coeff | Standardized coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Identification | .1058 | .1046 | .0624 | 1.6946 | .0918 | −.0174 | .2290 |

| Trust | .1208 | .1055 | .0891 | 1.3550 | .1771 | −.0551 | .2966 |

| Grounding | .5347 | .5088 | .0798 | 6.700 | .0000 | .3773 | .6922 |

| Outcome variable: Recommendation | |||||||

| Coeff | Standardized coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Identification | .2781 | .2749 | .0715 | 3.888 | .0001 | .1370 | .4192 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y | |||||||

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||

| TOTAL | .1723 | .0452 | .0842 | .2625 | |||

| Ind1 | .0363 | .0395 | −.0376 | .1196 | |||

| Ind2 | .0264 | .0313 | −.0290 | .0975 | |||

| Ind3 | .1096 | .0339 | .0495 | .1814 | |||

| Note: LLCI = Lower-level confidence interval; ULCI = Upper-level confidence interval. | |||||||

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davenport, T.; Guha, A.; Grewal, D.; Bressgott, T. How artificial intelligence will change the future of marketing. J Acad Mark Sci 2020, 48, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesing, B.; Peterson, S.J.; Michelsen, D. Artificial intelligence in logistics. DHL Customer Solut Innov 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg, P.B.; Følstad, A. Chatbots: changing user needs and motivations. Interactions 2018, 25, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, J.; Sullivan, J.; Prevost, S.; Churchill, E. Embodied Conversational Agents; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, S.S. The impact of the robot appearance types on social interaction with a robot and service evaluation of a robot. Arch Res 2014, 27, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartneck, C.; Forlizzi, J. A design-centred framework for social human-robot interaction. In RO-MAN. 13th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (IEEE Catalog No. 04TH8759), 2004; Volume 2004; pp. 591–594. [CrossRef]

- Eyssel, F.; Hegel, F. (S)he’s got the look: gender stereotyping of robots 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 2012, 42, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V. How artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping retailing. J Retailing 2018, 94, vi–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.H.; Rust, R.T. Artificial intelligence in service. J Serv Res 2018, 21, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, N.; Sharma, A. Waiting for a sales renaissance in the fourth Industrial Revolution: machine learning and artificial intelligence in sales research and practice. Ind Mark Manag 2018, 69, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M. Big data and analytics in tourism and hospitality: a perspective article. Tourism Rev 2020, 75, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Baggio, R.; Fuchs, M.; Höepken, W. Business intelligence and big data in hospitality and tourism: a systematic literature review. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 2018, 30, 3514–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Miracle, G.E.; Biocca, F. The effects of anthropomorphic agents on advertising effectiveness and the mediating role of presence. J Interact Advertising 2001, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.A.A.; Lee, K.M. The influence of regulatory fit and interactivity on brand satisfaction and trust in e-health marketing inside 3D virtual worlds (second life). Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2010, 13, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, T.; Van Nes, J.; Feldberg, F.; Van Dolen, W. Virtual customer service agents: using social presence and personalization to shape online service encounters. J Comput Mediated Commun 2014, 19, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, T. Living up to the chatbot hype: the influence of anthropomorphic design cues and communicative agency framing on conversational agent and company perceptions. Comput Hum Behav 2018, 85, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, R.; Silva, S.C.; Alparone, F.R. Millennials’ attitude toward chatbots: an experimental study in a social relationship perspective. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 2020, 48, 1213–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Wessel, M.; Benlian, A. AI-based chatbots in customer service and their effects on user compliance. Electron Markets 2021, 31, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Weaven, S.; Wong, I.A. Linking AI quality performance and customer engagement: the moderating effect of AI preference. Int J Hosp Manag 2020, 90, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Dautenhahn, K. A survey of socially interactive robots. Robot Auton Syst 2003, 42, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S. Toward a taxonomy of copresence. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ 2003, 12, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, E.; Sundar, S.S. Humanizing chatbots: the effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Comput Hum Behav 2019, 97, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Yen, C. The Man Who Lied to His Laptop: What Machines Teach Us About Human Relationships; Current: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y.; Green, N. Are machines gender neutral? Gender-stereotypic responses to computers with voices. J Appl Soc Psychol 1997, 27, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broverman, I.K.; Vogel, S.R.; Broverman, D.M.; Clarkson, F.E.; Rosenkrantz, P.S. Sex-role stereotypes: a current appraisal 1. J Soc Issues 1972, 28, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.; Glick, P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci 2007, 11, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton-James, C.E.; Tybur, J.M.; Grießer, V.; Costa, D. Stereotypes about surgeon warmth and competence: the role of surgeon gender. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0211890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilman, M.E. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res Organ Behav 2012, 32, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddy, L.; Terkildsen, N. Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. Am J Pol Sci 1993, 37, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Pol, G.; Park, J.W. The role of brand logos in firm performance. J Bus Res 2013, 66, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.E. The impact of brand concept on brand equity. Asia Pac J Innov Entrep 2017, 11, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; MacInnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J Mark 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J Mark 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J Mark 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J Mark Res 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J Mark 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J Con Res 1982, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraman, V.; Kwon, W.S.; Gilbert, J.E.; Ross, K. Should AI-based, conversational digital assistants employ social-or task-oriented interaction style? A task-competency and reciprocity perspective for older adults. Comput Hum Behav 2019, 90, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, M.; Janiszewski, C.; Neumann, M.M. The influence of avatars on online consumer shopping behavior. J Mark 2006, 70, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y. Machines and mindlessness: social responses to computers. J Soc Issues 2000, 56, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, D.; Tamborini, R.; Bowman, N.D. The effects of static avatars on impression formation across different contexts on social networking sites. Comput Hum Behav 2015, 53, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.L.; Fox, J. Avatars and ComputerMediated communication: a review of the definitions, uses, and effects of digital representations. Rev Commun Research 2018, 6, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Picard, R.W. Establishing and maintaining long-term human-computer relationships. ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 2005, 12, 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.; Fogg, B.J. Credibility and computing technology. Commun ACM 1999, 42, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Pantidi, N.; Cooney, O.; Doyle, P.; Garaialde, D.; Edwards, J.; Spillane, B.; Gilmartin, E.; Murad, C.; Munteanu, C.; Wade, V.; Cowan, B.R. What makes A good conversation? Challenges in designing truly conversational agents. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2019; p. 3300705.

- Madhavan, P.; Wiegmann, D.A. Similarities and differences between human–human and human–automation trust: an integrative review. Theor Issues Ergon Sci 2007, 8, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvitz, E. Principles of mixed-initiative user interfaces. In Proceedings of the S.I.G.C.H.I. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 1999; pp. 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogiorgos, D.; Pereira, A.; Gustafson, J. Grounding behaviours with conversational interfaces: effects of embodiment and failures. J Multimodal User Interfaces 2021, 15, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.C.; Dale, R. Looking to understand: the coupling between speakers’ and listeners’ eye movements and its relationship to discourse comprehension. Cogn Sci 2005, 29, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.S.; Jung, E.H.; Waddell, T.F.; Kim, K.J. Cheery companions or serious assistants? Role and demeanor congruity as predictors of robot attraction and use intentions among senior citizens. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2017, 97, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, A.L. Voices in and of the machine: source orientation toward mobile virtual assistants. Comput Hum Behav 2019, 90, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parulekar, A.A.; Raheja, P. Managing celebrities as brands: impact of endorsements on celebrity image. In Creating Images Psychol Mark Commun 2006, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.M.; Hill, R.P. The universality of warmth and competence: a response to brands as intentional agents. J Consum Psychol 2012, 22, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J. Enhancing user experience with conversational agent for movie recommendation: effects of self-disclosure and reciprocity. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2017, 103, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Looy, J.; Courtois, C.; De Vocht, M.; De Marez, L. Player identification in online games: validation of a scale for measuring identification in MMOGs. Media Psychol 2012, 15, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.; Wise, K.; Bolls, P. How avatar customizability affects children’s arousal and subjective presence during junk food–sponsored online video games. Cyberpsychol Behav 2009, 12, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Tuah, N.; Wanick, V.; Ranchhod, A.; Wills, G.B. Exploring avatar roles for motivational effects in gameful environments. EAI Endorsed Trans Creat Technol 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolin, K.; Kuss, D.J.; Nuyens, F.M.; Griffiths, M.D. ‘I am the character, the character is me’: a thematic analysis of the user-avatar relationship in videogames. Comput Hum Behav 2023, 143, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, S.G.; Kang, M. I became an attractive person in the virtual world: users’ identification with virtual communities and avatars. Comput Hum Behav 2012, 28, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, N.; Bailenson, J.N.; Ducheneaut, N. The Proteus effect: implications of transformed digital self-representation on online and offline behavior. Commun Res 2009, 36, 285–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.E. The effect of ideal avatar on virtual brand experience in XR platform. J Distrib Sci 2023, 21, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.W.; Lee, K.C. Exploring the value of purchasing online game items. Comput Hum Behav 2011, 27, 2178–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.; Cassell, J. Social dialogue with embodied conversational agents. Adv Nat Multimodal Dial Syst 2005, 30, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, H.; Castle Bell, G.C.; Minei, E.M.; Robinson, M.C. The relative effectiveness of active listening in initial interactions. Int J Listening 2014, 28, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H.H.; Brennan, S.E. Grounding in communication. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition; Resnick, L.B., Levine, J.M., Teasley, S.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, 1991; pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H.T.; Lemay, E.P., Jr.; Finkenauer, C. Toward understanding: the importance of feeling understood in relationships. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 2017, 11, e12308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, A.S.; Hildebrand, C.; Häubl, G. Machine talk: how verbal embodiment in conversational AI shapes consumer–brand relationships. J Consum Res 2023, 50, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, U. Performing embodied identity in virtual worlds. Eur J Inf Syst 2014, 23, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Exploring the fit of real brands in the second-life virtual 1 world. J Mark Manag 2011, 27, 934–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannidis, S.; Pantano, E.; See-To, E.W.K.; Bourlakis, M. Modelling the determinants of a simulated experience in a virtual retail store and users’ product purchasing intentions. J Mark Manag 2013, 29, 1462–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Fox, J.; Bailenson, J.N. Avatars. In Leadership in Science and Technology: A Reference Handbook; Bainbridge, W.S., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2012; pp. 695–702. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, M.; Poncin, I. The avatar in marketing: synthesis, integrative framework and perspectives. Rech Appl Mark (Engl Ed) 2013, 28, 85–115. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, R.P.; Zhang, K. Anthropomorphized helpers undermine autonomy and enjoyment in computer games. J Con Res 2016, 43, 282–302. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, A. ChatGPT: systematic review, applications, and agenda for multidisciplinary research. J Chin Econ Bus Stud 2023, 21, 193–212. [CrossRef]

- Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Laycock, R.; Spencer, S.J. A Chat(GPT) about the future of scientific publishing. Brain Behav Immun 2023, 110, 152–154. [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Brand | This brand represents the functional benefits that I can expect from the brand. This brand ensures that it assists me in handling my daily life competently. This brand represents a solution to certain problems. |

Jeon [31], Park et al. [30] |

| Experiential Brand | This brand expresses a luxurious image. I have to pay a lot to buy this brand. This brand makes life richer and more meaningful. |

|

| AI Agent Trust | I trust an AI agent. I have faith in the AI agent. This AI agent gives me a feeling of trust. |

Nass and Moon [41] |

| Grounding | This AI agent provided feedback of having understood my input. This AI agent provided feedback on having accepted my input. I felt that this AI agent understood what I had to say. |

Bergner et al. [68] |

| AI Agent Identification | This AI agent is similar to me. I identify with this AI agent. This AI agent and I are similar in reality. |

Schultze [69] Szolin et al. [59] |

| Recommendation | I would recommend this brand to my friends. If my friends were looking to buy a product, I would tell them to try this brand. |

Barnes and Mattsson [70] Papagiannidis et al. [71] |

| Brand Attitude | I like this brand. This brand makes me favorable. This brand is good. |

Jeon [31] Park et al. [34] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).