Submitted:

05 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Measuring ethical judgements: MES

1.2. MES strengths and weaknesses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and instruments

2.2.1. Scenarios: Adaptation and selection

- Classic: (a) the protagonist willingly chooses the action, without any rule or control of others; (b) the protagonist obtains a personal benefit from the action; (c) the scenario clearly identifies a victim of the action; and (d) the protagonist's action is the most questionable one described in the scenario.

- Conspiracy: (a) the protagonist willingly chooses the action, without any rule or control of others; (b) the protagonist obtains a personal benefit from the action; (c) the scenario does not clearly identify a victim of the action; and (d) the protagonist's action is not the most questionable one described in the scenario.

- Runaway trolley: (a) the protagonist willingly chooses the action, without any rule or control of others; (b) the protagonist does not obtain a personal benefit from the action; (c) the scenario clearly identifies a victim of the action; and (d) the protagonist's action is the most questionable one described in the scenario.

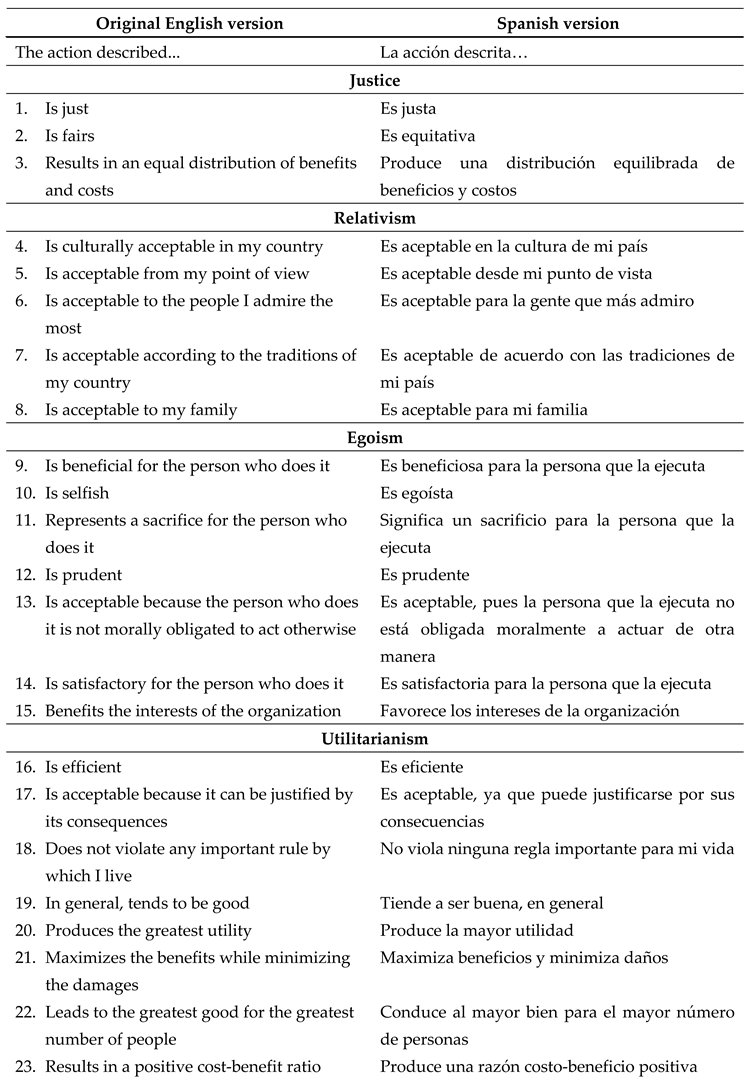

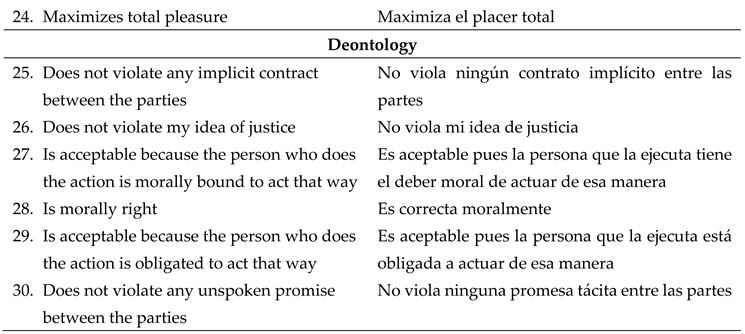

2.2.2. Spanish adaptation of the MES-30

2.2.3. Social desirability measurement

2.3. Data analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

| Classic | Conspiracy | Runaway trolley |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Appendix B.

| Items | GFS1 | SF S1 | GFS2 | SF S2 | GFS3 | SF S3 | GFS4 | SF S4 | GFS5 | SF S5 | GFS6 | SF S6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justice | ||||||||||||

| 1 | .87 | .30 | .94 | .27 | .95 | .16 | .94 | .24 | .94 | .18 | .95 | .30 |

| 2 | .91 | .37 | .93 | .29 | .93 | .41 | .92 | .33 | .93 | .40 | .96 | .29 |

| 3 | .80 | .26 | .89 | .21 | .89 | .11 | .88 | .26 | .93 | .23 | .89 | .15 |

| Relativism | ||||||||||||

| 4 | .57 | .68 | .53 | .77 | .59 | .71 | .55 | .81 | .64 | .74 | .54 | .76 |

| 5 | .97 | .12 | .98 | .09 | .96 | .06 | .98 | -.18 | .98 | .05 | .95 | .16 |

| 6 | .92 | .16 | .92 | .22 | .91 | .20 | .92 | -.16 | .94 | .13 | .90 | .25 |

| 7 | .57 | .75 | .59 | .74 | .61 | .76 | .55 | .73 | .65 | .68 | .54 | .82 |

| 8 | .94 | .16 | .94 | .20 | .94 | .17 | .94 | -.19 | .96 | .11 | .91 | .26 |

| Egoism | ||||||||||||

| 9 | .37 | .81 | .44 | .73 | .50 | .74 | .51 | .68 | .64 | .63 | .57 | .72 |

| 10 | -.20 | .25 | .01 | .60 | .12 | .44 | .20 | .44 | .11 | .51 | .28 | .49 |

| 11 | .54 | .02 | .69 | -.19 | .60 | .09 | .68 | .07 | .60 | .20 | .72 | .14 |

| 12 | .87 | -.14 | .92 | -.23 | .91 | -.25 | .97 | -.20 | .94 | -.05 | .94 | -.16 |

| 13 | .89 | -.06 | .86 | -.09 | .86 | -.06 | .91 | -.06 | .92 | .00 | .91 | -.06 |

| 14 | .34 | .66 | .49 | .78 | .56 | .65 | .56 | .77 | .70 | .62 | .64 | .56 |

| 15 | .90 | -.12 | .53 | .50 | .79 | .30 | .76 | .31 | .78 | .28 | .74 | .42 |

| Utilitarianism | ||||||||||||

| 16 | .86 | .10 | .81 | .17 | .86 | .25 | .86 | .15 | .93 | .14 | .91 | .18 |

| 17 | .92 | .05 | .90 | .06 | .89 | .10 | .93 | .05 | .95 | .02 | .92 | .15 |

| 18 | .87 | -.12 | .88 | -.08 | .91 | -.16 | .94 | -.03 | .96 | -.04 | .92 | .00 |

| 19 | .95 | .07 | .94 | -.00 | .94 | .02 | .96 | .06 | .95 | .11 | .95 | .06 |

| 20 | .85 | .27 | .62 | .25 | .79 | .33 | .81 | .32 | .87 | .29 | .82 | .12 |

| 21 | .87 | .19 | .82 | .38 | .86 | .29 | .87 | .35 | .91 | .28 | .86 | .27 |

| 22 | .94 | .15 | .90 | .08 | .83 | .35 | .90 | .25 | .92 | .27 | .92 | .19 |

| 23 | .89 | .25 | .83 | .36 | .85 | .39 | .87 | .37 | .91 | .28 | .88 | .36 |

| 24 | .73 | .39 | .79 | .34 | .81 | .29 | .79 | .31 | .87 | .27 | .83 | .35 |

| Deontology | ||||||||||||

| 25 | .83 | .26 | .76 | .41 | .86 | .36 | .90 | .18 | .92 | .17 | .92 | .16 |

| 26 | .86 | .37 | .90 | .03 | .89 | .13 | .93 | .19 | .95 | .07 | .96 | .08 |

| 27 | .90 | .14 | .91 | .08 | .94 | .10 | .94 | .16 | .93 | .29 | .94 | .09 |

| 28 | .96 | .05 | .92 | .12 | .94 | .09 | .94 | .21 | .96 | .11 | .98 | .02 |

| 29 | .90 | .11 | .91 | .09 | .91 | .12 | .90 | .22 | .93 | .29 | .93 | .11 |

| 30 | .88 | .06 | .81 | .60 | .86 | .41 | .88 | .22 | .94 | .18 | .93 | .28 |

References

- Razzaque, M. A.; Hwee, T. P. Ethics and purchasing dilemma: A Singaporean view. Journal of Business Ethics, 2002, 35, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J. M.; Harvey, R. J. The effect of moral intensity on ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 2007, 72, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. T.; Biderman, M. D. Studying ethical judgments and behavioral intentions using structural equations: evidence from the multidimensional ethics scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 2008, 83, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D. P.; Reidenbach, R. E.; Babin, B. J. The nature, measurement, and stability of ethical judgments in the workplace. Psychologicul Reports, 1997, 80, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R. Encouraging classroom discussion of ethical dilemmas in research management: Three vignettes. Teaching Business Ethics, 2001, 5, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R. Tackling ethical dilemmas in project management using vignettes. International Journal of Project Management, 2002, 20, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, D. C.; Sevigny, P. R.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Paholpak, S. Validity of the Multidimensional Ethics Scale for a sample of Thai physicians. South East Asian Journal of Medical Education, 2012, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R. S. A multidimensional scale for measuring business ethics: A purification and refinement. Journal of Business Ethics, 1992, 11, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesschalck, J. Making behavioral ethics research more useful for ethics management practice: Embracing complexity using a design science approach. Journal of Business Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L. K.; Weaver, G. R.; Reynolds, S. J. Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 2006, 32, 951–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J. Moral development: Advances in research and theory. Praeger 1986.

- Jones, T. M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Paláu, S. Ethical evaluations, intentions, and orientations of accountants: Evidence from a cross-cultural examination. International Advances in Economic Research, 2001, 7, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudrack, P. E.; Mason, E. S. Dilemmas, conspiracies, and Sophie’s choice: vignette themes and ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Robin, D.P.; Babin, L. Making sense of the research on gender and ethics in business: A critical analysis and extension. Business Ethics Quarterly, 1997, 7, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D. P.; Reidenbach, R. E.; Forrest, P. J. The perceived importance of an ethical issue as an influence on the ethical decision-making of ad managers. Journal of Business Research, 1996, 35, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Addison-Wesley. 1975.

- Flory, S. M.; Phillips, T. J.; Reidenbach, R. E.; Robin, D. P. A multidimensional analysis of selected ethical issues in accounting. The Accounting Review, 1992, 67, 284–302. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrack, P. E.; Mason, E. S. Ethical judgments: What do we know, where do we go? Journal of Business Ethics, 2013, 115, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Y.; Ho, Y. H. An examination of cultural differences in ethical decision making using the Multidimensional Ethics Scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 2008, 36, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nill, A.; Schibrowsky, J. A. The impact of corporate culture, the reward system, and perceived moral intensity on marketing students' ethical decision making. Journal of Marketing Education, 2005, 27, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, W. J. , & Gunawong, P. Cultural dimensions and moral reasoning: A comparative study. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 2016, 36, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, J.; Nwachukwu, O. Cross-cultural business ethics: Ethical beliefs difference between blacks and whites. Journal of Business Ethics, 1988, 7, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenburg, T. L.; Valentine, S. R. Spanish and American executives’ ethical judgments and intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 2002, 38, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, J.; LaTour, M. S. Bribery and extortion in international business: Ethical perceptions of Greeks compared to Americans. Journal of Business Ethics, 1995, 14, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, J.; Nwachukwu, O. A comparison of Nigerian to American views of bribery and extortion in international commerce. Journal of Business Ethics, 1991, 10, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S. R.; Ritternburg, T. L. Spanish and American business professionals’ ethical evaluations in global situations. Journal of Business Ethics, 2004, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Paláu, S. Fundamentos morales de las evaluaciones éticas de los contadores: Estudio empírico de Latinoamérica y Estados Unidos. Forum Empresarial, 2008, 13, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidenbach, R. E.; Robin, D. P. Some initial steps toward improving the measurement of ethical evaluations of marketing activities. Journal of Business Ethics, 1988, 7, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Pant, L.; Sharp, D. A validation and extension of a Multidimensional Ethics Scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 1993, 12, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J. A multidimensional approach to Finnish managers’ moral decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 2001, 34, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J. M.; Harvey, R. J. Psychometric properties of the Reidenbach–Robin Multidimensional Ethics Scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 2007, 72, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, G. L. Developing a multidimensional scale for ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 2011, 104, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. R.; Pant, L. W.; Sharp, D. J. An examination of differences in ethical decision-making between Canadian business students and accounting professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 2001, 30, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. A multidimensional ethics scale for Indian managers' moral decision making. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies, 2010, 15, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reidenbach, R. E.; Robin, D. P. Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 1990, 9, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, H. Reidenbach and Robin’s Multidimensional Ethics Scale: Testing a second-order factor model. Psychology Research, 2014, 4, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. W.; Dawson, L. E. Personal religiousness and ethical judgements: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 1996, 15, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. R.; Pant, L. W.; Sharp, D. J. The effect of gender and academic discipline diversity on the ethical evaluations, ethical intentions and ethical orientations of potential public accounting recruits. Accounting Horizons, 1998, 12, 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, R. Support for Reidenbach and Robin’s (1990) eight-item Multidimensional Ethics Scale. The Social Science Journal, 2004, 41, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C. A.; Shafer, W. E.; Strawser, J. R. A multidimensional analysis of tax practitioners’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 2000, 24, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, J.; Ortiz-Buonafina, M. Ethical beliefs' differences of males and females. Journal of Business Ethics, 1990, 9, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTour, M. S.; Henthorne, T. L. Ethical judgments of sexual appeals in print advertising. Journal of Advertising, 1994, 23, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornoff, R. J.; Tankersley, C. B. Perceptual differences in market transactions: A source of consumer frustration. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 1975, 97, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, M. R. A critique and revision of the Multidimensional Ethics Scale. Journal of Empirical Generalisations in Marketing Science, 1996, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Centurión-Rodríguez, C.; Aburto-Moreno, M.; Castillo-Minaya, E.; Huamán-Saavedra, J. Juicio ético académico de estudiantes de medicina de preclínicas y clínicas: Aplicación de una Escala Multidimensional Ética. Ciencia e Investigación Médica Estudiantil Latinoamericana, 2014, 19, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shawver, T. J.; Sennetti, J. T. Measuring ethical sensitivity and evaluation. Journal of Business Ethics, 2009, 88, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, R.; Hyman, M. R.; Brown, G. Ethical judgments about wartime ads depicting combat. Journal of Advertising, 1992, 21, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, R.; Hyman, M. R. On measuring ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 1993, 12, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, M. R.; Steiner, S. D. The vignette method in business ethics research: Current uses, limitations, and recommendations. Society for Marketing Advances Conference Proceedings, 1996; https://www.academia.edu/6643244/The_vignette_method_in_business_ethics_research_Current_uses_a nd_recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R. D.; Ferrando, P, J. ; Tosi, J. D. Uso del análisis factorial exploratorio en RIDEP: Recomendaciones para autores y revisores. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 2019, 52, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P. M.; Brown, G.; Widing, R. E. The association of ethical judgment of advertising and selected advertising effectiveness response variables. Journal of Business Ethics, 1998, 17, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, R.; Brown, G.; Hyman, M. R.; Dawson, L. E. Personal moral philosophies and the moral judgments of salespersons. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 1994, XIV, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, T. S.; Griffith, D. The evaluation of IT ethical scenarios using a multidimensional scale. Advances in Information Systems, 2001, 32, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidenbach, R. E.; Robin, D. P.; Dawson, L. An application and extension of a Multidimensional Ethics Scale to selected marketing practices and marketing groups. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1991, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct, 2017. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code.

- McMahon, J. M. An analysis of the factor structure of the multidimensional ethics scale and a perceived moral intensity scale, and the effects of moral intensity on ethical judgment [Unpublished Doctoral dissertation]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Blacksburg, Virginia. 2002. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/27855.

- Marques, P. A.; Azevedo-Pereira, J. Ethical ideology and ethical judgments in the Portuguese accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 2009, 86, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, R. R. The effects of gender and setting on accountants’ ethically sensitive decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 2000, 24, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Miller, G. Ethical orientation and awareness of tourism students. Journal of Business Ethics, 2005, 62, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeros, R.; Plank, R. E. How ethical are purchasing management professionals? Journal of Business Ethics, 1996, 15, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Molina, G.; Orta-Pérez, M. La experiencia y el comportamiento ético de los auditores: Un estudio empírico. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 2005, 34, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T. R. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management, 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santalla-Banderali, Z.; Malavé, J. Individual and situational influences on the propensity for unethical behavior in response to organizational scenarios. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 2022, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D. G.; Fick, C. Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 1993, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Sanz, J.; Espinosa, R.; Gesteira, C.; García-Vera, M. P. La Escala de Deseabilidad Social de Marlowe-Crowne: Baremos para la población general española y desarrollo de una versión breve. Anales de Psicología, 2016, 32, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R.; Thorpe, K. Confirmatory factor analyses of the full and short versions of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. The Journal of Social Psychology, 2000, 140, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W. M. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1982, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöber, J. The Social Desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17): Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and relationship with age. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 2001, 17, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P. J.; Chico, E. Adaptación y análisis psicométrico de la escala de deseabilidad social de Marlowe y Crowne. Psicothema, 2000, 12, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Beretvas, S. N.; Meyers, J. L.; Leite, W. L. A reliability generalization study of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 2002, 62, 570–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. M.; Ritchie, T. D.; Hepper, E. G.; Gebauer, J. E. The Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding Short Form (BIDR-16). SAGE Open 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederhof, A. J. Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1985, 15, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L.; Reid, D. B. Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1991, 60, 307–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatman, A. W.; Kreamer, S. Psychometric properties of the Social Desirability Scale-17 with Individuals on probation and parole in the United States. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 2014, 9, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Von de Mortel, T. F. Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2008, 25, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, D. M.; Fernandes, M. F. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, B. F.; Valdiserri, J.; Neuendorf, K. A.; Nemeth, J. Validity of the SDS-17 measure of social desirability in the American context. Personality and Individual Differences, 2006, 40, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, A.; Manganelli, A. M. Measuring social desirability responding. A short version of Paulhus’ BIDR 6. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 2011, 18, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kroner, D. G.; Weekes, J. R. Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding: factor structure, reliability, and validity with an offender sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 1996, 21, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. The Lavaan tutorial. Department of Data Analysis: Ghent University. 2014.

- Asún, R. A.; Rdz-Navarro, K.; Alvarado, J. M. Developing multidimensional Likert scales using item factor analysis: The case of four-point items. Sociological Methods & Research, 2016, 45, 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 7: A guide to the program and applications. Scientific Software International 1989.

- Brown, T.A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd ed., Guilford Publications. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, G.; Brachel, R. Multiple-Group confirmatory factor analysis in R – A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 2014, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Kellaris, J. J. Toward understanding marketing students' ethical judgment of controversial personal selling practices. Journal of Business Research, 1992, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.; Valentine, S. Issue contingencies and marketers’ recognition of ethical issues, ethical judgments and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Research, 2004, 57, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, H. F. Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession: An extension of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 2005, 61, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J. M.; Harvey, R. J. An analysis of the factor structure of Jones' moral intensity construct. Journal of Business Ethics, 2006, 64, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S. J.; Patwardhan, A. The role of moral intensity and moral philosophy in ethical decision making: A crosscultural comparison of China and the European Union. Business Ethics: A European Review, 2008, 17, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CLASSIC | ||

|---|---|---|

| Authors | English versions | Spanish versions |

| Hudson & Miller [61, p. 394]: Scenario 6. |

Scenario 1A travel agent is responsible for selling excursions to customers who have purchased package tours once they arrive at their destinations. Excursions are an important part of the travel agency's income, which depends on the high-pressure sales techniques the agents use to sell them. The agent feels that, despite working hard and for long hours, the remuneration received is not enough for a decent life. Then, the agent thinks that, since most customers pay in cash, it could be possible to keep some of the money they pay for the excursions without reporting it to the company. Action: the travel agent decides to keep the money payed in cash by two customers per excursion, thus obtaining $50 per week. |

Un agente de viajes se encarga de vender excursiones a los clientes que han adquirido paquetes turísticos, cuando llegan al destino. Las excursiones forman parte importante del ingreso de la agencia de viajes, el cual depende de las tácticas de alta presión de los agentes para venderlas. El agente siente que, a pesar de trabajar duro y durante largas horas, no gana suficiente para vivir dignamente. Entonces piensa que, como la mayoría de los clientes paga en efectivo, podría quedarse con el dinero que pagan algunas personas por las excursiones, sin reportarlo a la compañía. Acción: El agente de viajes decide quedarse con el efectivo de dos clientes por excursión y obtener, así, 50 dólares por semana. |

| Reidenbach & Robin [29,36]: Scenario C |

Scenario 2A supermarket chain operates several stores in a city, including one in a poor neighborhood. Different independent studies have shown that such store has higher prices and less products available than the stores from other areas. Action: when this area of the city receives the financial aid offered by the government, the store manager increases the prices of all goods. |

Una cadena de supermercados opera varias tiendas en una ciudad, incluyendo una en un barrio marginal. Varios estudios independientes han mostrado que, en la tienda del barrio, los precios tienden a ser mayores y la variedad de productos menor, que en las tiendas de otras zonas. Acción: El día en que llegan las ayudas monetarias del gobierno a esta área de la ciudad, el gerente de la tienda aumenta los precios de todas las mercancías. |

| CONSPIRACY | ||

| Kujala [31, p. 233]: Scenario “Hiding Money in Deals” |

Scenario 3A company will receive a large order from a foreign customer, if the manager accepts overpricing it and wiring such amount through a middleman to a customer's Swiss bank account. Upon analyzing the matter, the manager concludes there is no risk of being caught. The order would guarantee the company 18 months of work. Action: the manager takes the deal. |

Una compañía recibirá un gran pedido del extranjero, si el gerente acepta cobrar un exceso sobre el precio y transferir, a través de un intermediario, ese monto a una cuenta del cliente en un banco suizo. Al examinar el asunto, el gerente concluye que no corre riesgo de ser capturado. El pedido garantizaría año y medio de trabajo para la compañía. Acción: El gerente decide aceptar el arreglo. |

| Tsalikis & LaTour [25] and Tsalikis & Nwachukwu [26]: Scenario 1A-F1 |

Scenario 4A businessman contacts a government official of his country. The businessman offers the government official a large amount of money for "helping" him get a contract with the government. Action: the businessman convinces the government official to take the money and "help" him getting the contract. |

Un empresario contacta a un funcionario del gobierno de su país. El empresario ofrece al funcionario pagarle una gran suma de dinero por su "ayuda" para obtener un contrato con el gobierno. Acción: El empresario convence al funcionario de aceptar el dinero y "ayudarlo" a obtener el contrato. |

| RUNAWAY TROLLEY | ||

| Landeros & Plank [62, p. 793]: Scenario “Purchasing Morality” |

Scenario 5 Different matters are discussed during a meeting of the Procurement Department (PD). A professional from the PD tells the scenario of a salesman who called him and suggested him that he would donate 100 USD to his favorite charity organization, as long as the professional provided him with insider information about a recently closed tender. The buyer consulted this with his supervisor, who told him to do it, since this would not cause any damage. Action: the buyer provides the salesman with the information requested and took a check for 100 USD to donate to UNICEF. |

En una reunión del Departamento de Compras (DC) se discuten diversos asuntos. Un profesional del DC relata el escenario de un vendedor que lo llamó y le sugirió que, si le proporcionaba información privilegiada sobre una licitación recién concluida, donaría 100 dólares a su organización benéfica favorita. El comprador consultó a su supervisor, quien le dijo que lo hiciera, pues no ocasionaría daño alguno. Acción: El comprador le proporcionó al vendedor la información requerida y aceptó un cheque por 100 dólares para donarlo a UNICEF. |

| Radtke [60]: Scenario 7 |

Scenario 6Andrade and Salazar, two of Martinez's best friends, are engaged in an argument over the contract of sale of a used vehicle displayed at the dealership where Martinez and Andrade work as salesmen. Some years ago, this vehicle was involved in an accident that Martinez witnessed, but Salazar does not know about it. The vehicle suffered substantial damage, but it was repaired. Now, Andrade is showing the vehicle as if it had never been involved in an accident. It is difficult to determine the price difference of the vehicle. Action: Martinez decides not to tell Salazar that the vehicle was involved in an accident. |

Andrade y Salazar, dos de los mejores amigos de Martínez, están enfrascados en una discusión por la compra-venta de un vehículo usado, expuesto en el concesionario donde trabajan Martínez y Andrade como vendedores. Hace varios años el vehículo estuvo involucrado en un accidente del cual Martínez fue testigo, pero Salazar no lo sabe. El vehículo sufrió daños sustanciales, pero fue reparado. Ahora Andrade está presentando el vehículo como si nunca hubiera sufrido un accidente. Es difícil determinar la diferencia en el precio del vehículo. Acción: Martínez decide no contarle a Salazar que el vehículo sufrió un accidente. |

| Scenario | χ2 (375) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | 5F χ2 diff (20) |

1F χ2 diff (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 309.201 | 0.991 | 0.990 | 0.035 [0.031-0.040] | 0.036 | 960.80* | 218.04* |

| S2 | 1.328.925* | 0.965 | 0.959 | 0.071 [0.067-0.075] | 0.086 | 1415.02* | 326.37* |

| S3 | 1.076.105* | 0.977 | 0.973 | 0.070 [0.067-0.074] | 0.064 | 1063.45* | 469.93* |

| S4 | 1.072.723* | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.070 [0.066-0.074] | 0.070 | 1127.11* | 379.68* |

| S5 | 747.813* | 0.990 | 0.989 | 0.073 [0.069-0.076] | 0.037 | 1197.41* | 491.91* |

| S6 | 1.320.642* | 0.980 | 0.977 | 0.077 [0.074-0.081] | 0.071 | 855.92* | 363.22* |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECV-G (%) | 86.253 | 81.808 | 84.792 | 85.178 | 88.004 | 86.322 |

| ωh | .926 | .914 | .935 | .931 | .961 | .934 |

| Scenario | χ2 (90) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 96.339 | 0.988 | 0.986 | 0.064 [0.057-0.072] | 0.024 |

| S2 | 149.568* | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.073 [0.065-0.080] | 0.030 |

| S3 | 172.666* | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.085 [0.077-0.092] | 0.026 |

| S4 | 145.175* | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.076 [0.069-0.084] | 0.023 |

| S5 | 247.867* | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.106 [0.099-0.113] | 0.019 |

| S6 | 222.754* | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.080 [0.073-0.088] | 0.025 |

| Items | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justice | ||||||

| 1 | .894 | .959 | .965 | .957 | .959 | .987 |

| 2 | .936 | .953 | .951 | .946 | .961 | .990 |

| 3 | .814 | .908 | .876 | .883 | .948 | .891 |

| Relativism | ||||||

| 5 | .975 | .983 | .962 | .979 | .978 | .959 |

| 6 | .929 | .941 | .928 | .935 | .943 | .926 |

| 8 | .948 | .953 | .950 | .948 | .968 | .928 |

| Egoism | ||||||

| 11 | .528 | .712 | .603 | .677 | .585 | .702 |

| 12 | .872 | .916 | .919 | .961 | .937 | .936 |

| 13 | .889 | .855 | .860 | .905 | .909 | .896 |

| Utilitarianism | ||||||

| 17 | .918 | .892 | .884 | .926 | .943 | .913 |

| 18 | .864 | .874 | .912 | .940 | .956 | .921 |

| 19 | .943 | .931 | .938 | .952 | .945 | .950 |

| Deontology | ||||||

| 26 | .868 | .895 | .905 | .939 | .954 | .961 |

| 28 | .946 | .915 | .944 | .953 | .965 | .974 |

| 30 | .868 | .793 | .864 | .875 | .933 | .928 |

| Adapted MES-30 | Spanish MES-15 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | BI | PI | SI | EE | SD | BI | PI | SI | EE | SD |

| S1 | .707 | .465 | .468 | .755 | .084* | .746 | .432 | .416 | .793 | .019 |

| S2 | .749 | .552 | .533 | .737 | .137** | .844 | .521 | .482 | .839 | .044 |

| S3 | .748 | .590 | .608 | .724 | .218** | .851 | .565 | .573 | .826 | .152** |

| S4 | .750 | .571 | .526 | .696 | .218** | .836 | .536 | .491 | .805 | .094* |

| S5 | .866 | .726 | .723 | .868 | .104* | .906 | .714 | .702 | .910 | .065 |

| S6 | .801 | .578 | .577 | .769 | .204** | .890 | .554 | .550 | .851 | .144** |

| Scenario | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | 282.78*** | ||||

| S3 | 278.26* | 348.88*** | |||

| S4 | 250.35* | 310.87*** | 326.32* | ||

| S5 | 355.73*** | 409.70*** | 427.76* | 399.63* | |

| S6 | 328.20* | 392.01*** | 406.61*** | 406.61 | 406.61** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).