Submitted:

07 February 2024

Posted:

08 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

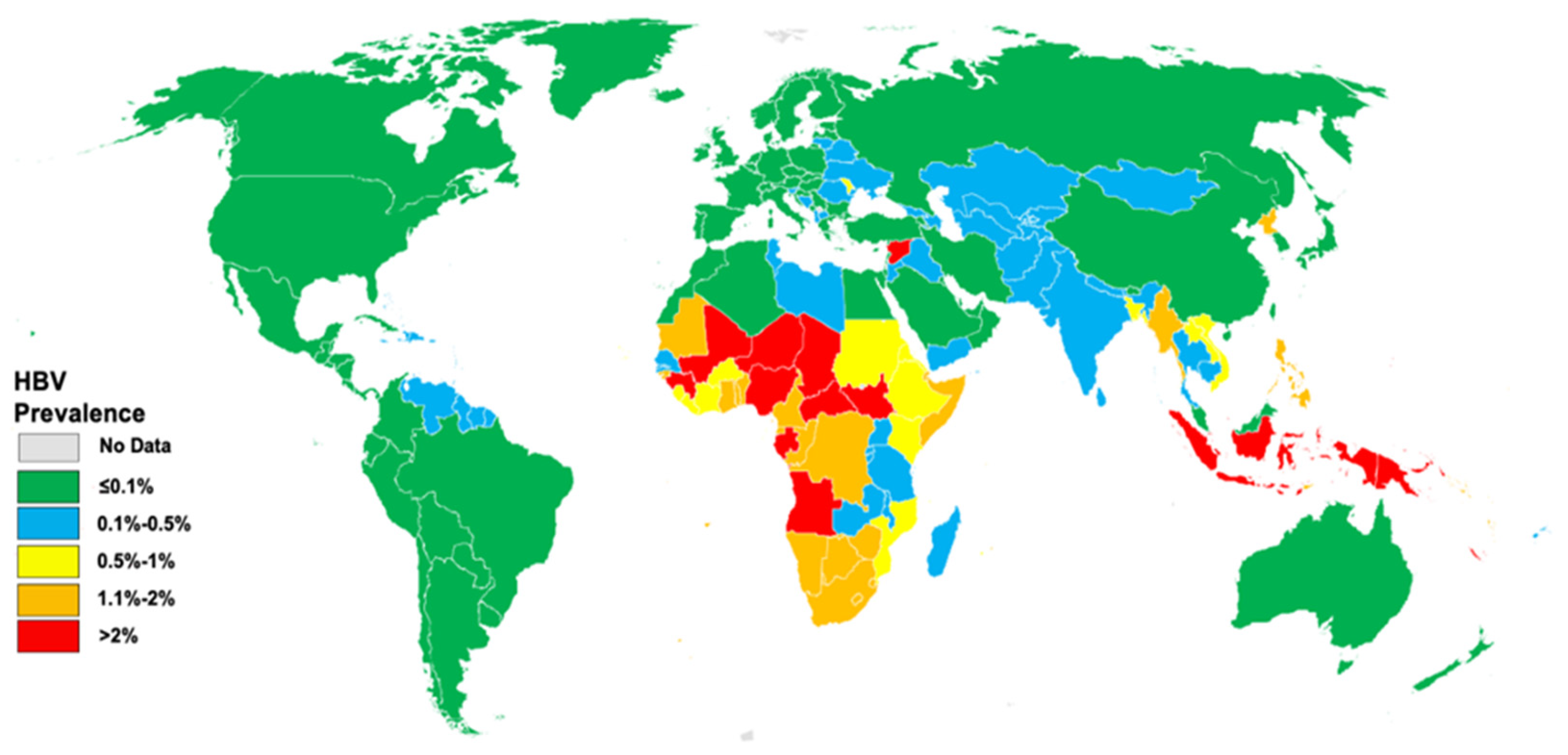

1.1. Overview of hepatitis B and its global impact

1.2. Significance of achieving HBV elimination by 2030

- Infant vaccination: Administering the three-dose HBV vaccine to infants.

- Preventing mother-to-child transmission (MTCT): Using either the HBV birth dose vaccine or alternative approaches.

- Ensuring blood and injection safety: Implementing protocols to minimize transmission through unsafe medical practices.

- Harm reduction: Implementing strategies to reduce transmission among high-risk groups like intravenous drug users.

2. Methodology

3. Hepatitis B Vaccines: Evolution and Effectiveness

3.1. From Plasma to Recombinant: A Paradigm Shift

3.2. Efficacy and Safety of HBV Vaccination

3.3. Concerns with HBV vaccination

3.3.1. Durability of the immune response

3.3.2. Vaccine escape mutants

3.3.3. Impact of HBV genotypic variability

3.3.4. Vaccine non-responders

3.4. Vaccine for healthcare workers

3.5. Cost-effectiveness of HBV vaccination

3.6. Recent advances in HBV vaccination

3.6.1. AI applications

3.6.2. Therapeutic HBV vaccine

3.7. The effectiveness of the HBV vaccine in different populations

3.7.1. Vaccination for High-risk populations

3.7.1.1. Pre-exposure high-risk groups

3.7.1.2. Patients with End-stage Kidney diseases

3.7.1.3. Post-Renal Transplant Patients

3.7.1.4. Men having sex with Men (MSM)

3.7.1.5. HIV patients

3.7.1.6. Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

3.7.1.7. Post-Liver Transplant patients

3.7.1.8. Mother-to-Child Transmission (MTCT) setting

3.7.2. HBV mass vaccination

3.7.2.1. Effect on chronic HBV infection

3.7.2.2. Effect on diseases related to acute HBV infection

3.7.2.3. Effect on Diseases related to chronic HBV infection

3.7.2.4. Effect on Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC):

4. Global Impact of HBV Vaccination Programs: Successes and Challenges

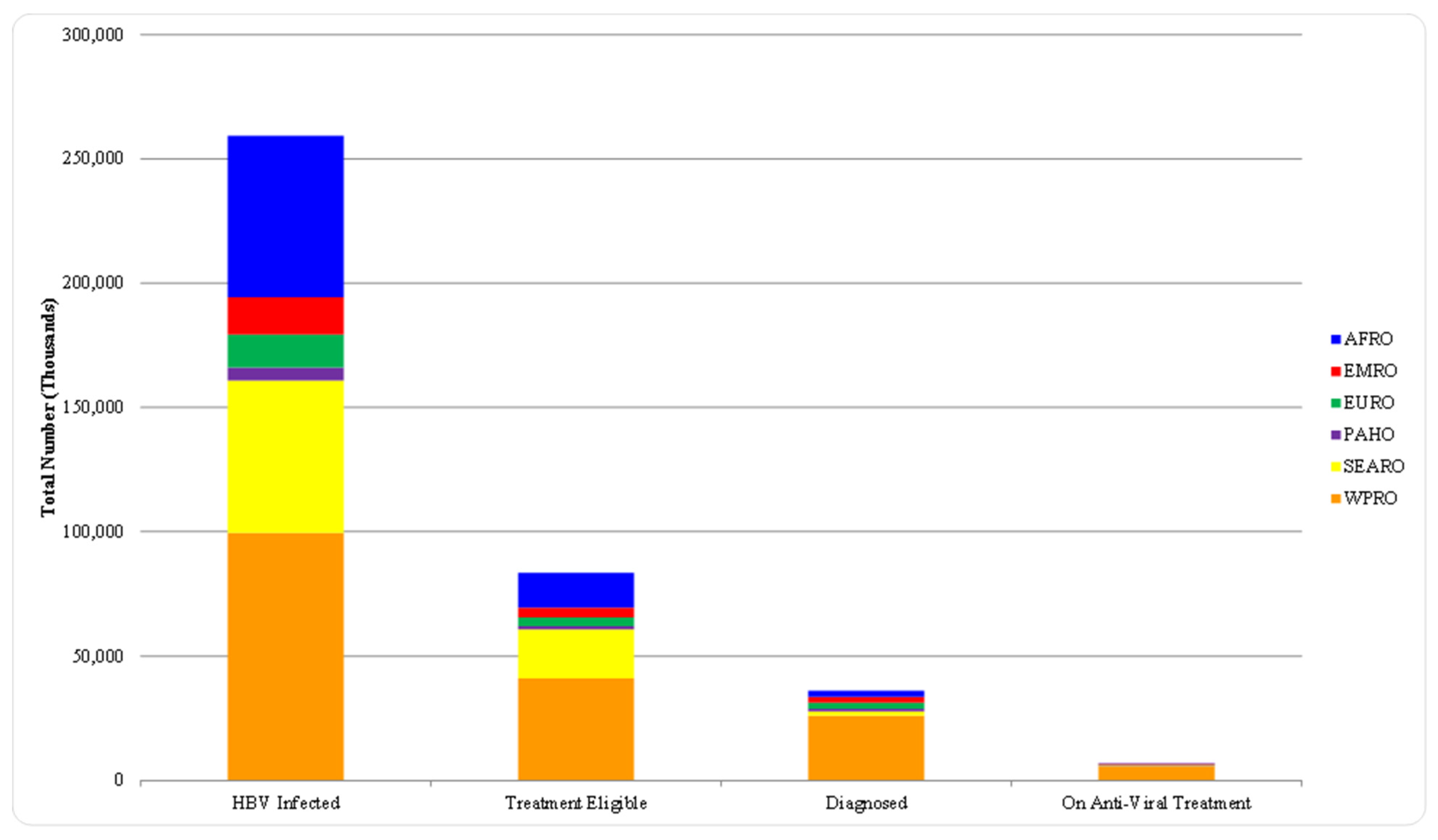

5. Progress Towards Achieving WHO Targets for 2030 HBV Elimination: 2016-2023

5.1. Impact of HBV vaccination

5.2. The Feasibility of HBV Elimination by 2030

5.3. Effect of COVID-19 on the 2030 elimination plan

5.4. Key areas of progress towards the 2030 elimination goals:

5.5. Strategies for Achieving HBV Elimination by 2030

6. The Road Ahead: Sustaining Progress Beyond 2030

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Locarnini, A. Hatzakis, D. S. Chen, and A. Lok, ‘Strategies to control hepatitis B: Public policy, epidemiology, vaccine and drugs’, J Hepatol, vol. 62, no. 1 Suppl, pp. S76–S86, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Spearman et al., ‘Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 2, no. 12, p. 900, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Stanaway et al., ‘The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013′, Lancet, vol. 388, no. 10049, pp. 1081–1088, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kao, P. J. Chen, and D. S. Chen, ‘Recent Advances in the Research of Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Epidemiologic and Molecular Biological Aspects’, Adv Cancer Res, vol. 108, no. C, pp. 21–72, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Fattovich, T. Stroffolini, I. Zagni, and F. Donato, ‘Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Incidence and risk factors’, Gastroenterology, vol. 127, no. 5, pp. S35–S50, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. S. F. Lok, ‘Chronic hepatitis B’, N Engl J Med, vol. 346, no. 22, pp. 1682–1683, May 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. Ibrahim, S. El Din, and I. Bazzal, ‘Antibody level after hepatitis-B vaccination in hemodialysis patients: impact of dialysis adequacy, chronic inflammation, local endemicity and nutritional status.’, J Natl Med Assoc, vol. 98, no. 12, p. 1953, Dec. 2006, Accessed: Dec. 29, 2023. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC2569692/?report=abstract.

- A. P. Venook, C. Papandreou, J. Furuse, and L. Ladrón de Guevara, ‘The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective’, Oncologist, vol. 15 Suppl 4, no. S4, pp. 5–13, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Stevens et al., ‘Perinatal Hepatitis B Virus Transmission in the United States: Prevention by Passive-Active Immunization’, JAMA, vol. 253, no. 12, pp. 1740–1745, Mar. 1985. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Stevens, R. P. Beasley, J. Tsui, and W.-C. Lee, ‘Vertical transmission of hepatitis B antigen in Taiwan’, N Engl J Med, vol. 292, no. 15, pp. 771–774, Apr. 1975. [CrossRef]

- WHO, ‘Global Health Sector Strategies on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and the sexually transmitted infections’, World Health Organization, vol. ector stra, no. June 2021, pp. 2022–2030, 2021, Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077.

- D. Razavi-Shearer et al., ‘Global prevalence, cascade of care, and prophylaxis coverage of hepatitis B in 2022: a modelling study’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 879–907, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Jaquet, G. Muula, D. K. Ekouevi, and G. Wandeler, ‘Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Epidemiological Research Gaps’, Current Epidemiology Reports 2021 8:3, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 89–96, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ding, X. Sun, Y. Xu, L. Yang, Y. Zhang, and Q. Shen, ‘Association Between Income and Hepatitis B Seroprevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, Hepatitis Monthly 2020 20:10, vol. 20, no. 10, p. 104675, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- ‘Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis’. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06.

- T. Solomon-Rakiep, J. Olivier, and E. Amponsah-Dacosta, ‘Weak Adoption and Performance of Hepatitis B Birth-Dose Vaccination Programs in Africa: Time to Consider Systems Complexity?-A Scoping Review’, Trop Med Infect Dis, vol. 8, no. 10, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Razavi-Shearer et al., ‘Global prevalence, cascade of care, and prophylaxis coverage of hepatitis B in 2022: a modelling study’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 879–907, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Howell et al., ‘Pathway to global elimination of hepatitis B: HBV cure is just the first step’, Hepatology, vol. 78, no. 3, p. 976, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. McCulloch, N. Romero, J. MacLachlan, N. Allard, and B. Cowie, ‘Modeling Progress Toward Elimination of Hepatitis B in Australia’, Hepatology, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1170–1181, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Cox et al., ‘Progress towards elimination goals for viral hepatitis’, Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020 17:9, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 533–542, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Waheed, M. Siddiq, Z. Jamil, and M. H. Najmi, ‘Hepatitis elimination by 2030: Progress and challenges’, World J Gastroenterol, vol. 24, no. 44, p. 4959, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Elsharkawy, R. Samir, M. Abdallah, M. Hassany, and M. El-Kassas, ‘The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis B and C elimination programs in Egypt: current situation and future perspective’, Egyptian Liver Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- ‘Global Viral Hepatitis: Millions of People are Affected | CDC’. Accessed: Dec. 23, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/global/index.htm.

- S. Chen, W. Mao, L. Guo, J. Zhang, and S. Tang, ‘Combating hepatitis B and C by 2030: achievements, gaps, and options for actions in China’, BMJ Glob Health, vol. 5, no. 6, p. 2306, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Cui et al., ‘Global reporting of progress towards elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 332–342, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Geneva: World Health Organization, ‘Global health sector stategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexual transmitted infections for the period 2022-2030′, Braz Dent J., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2022.

- S. M. F. Akbar, M. Al-Mahtab, S. Khan, O. Yoshida, and Y. Hiasa, ‘Elimination of Hepatitis by 2030: Present Realities and Future Projections’, Infectious Diseases and Immunity, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 3–8, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Luo, L. Li, and B. Ruan, ‘Impact of the implementation of a vaccination strategy on hepatitis B virus infections in China over a 20-year period’, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. e82–e88, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Chitnis and R. J. Wong, ‘Review of Updated Hepatitis B Vaccine Recommendations and Potential Challenges With Implementation’, Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y), vol. 18, no. 8, p. 447, Aug. 2022, Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC9666805/.

- J. H. Kao and D. S. Chen, ‘Global control of hepatitis B virus infection’, Lancet Infect Dis, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 395–403, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, X. Zhou, and Y. H. Zhou, ‘Hepatitis B vaccine development and implementation’, Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1533–1544, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Van Damme, ‘Long-term Protection After Hepatitis B Vaccine’, J Infect Dis, vol. 214, no. 1, pp. 1–3, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Hilleman, W. J. McAleer, E. B. Buynak, and A. A. McLean, ‘The preparation and safety of hepatitis B vaccine’, vol. 7, pp. 3–8. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Francis et al., ‘The Safety of the Hepatitis B Vaccine: Inactivation of the AIDS Virus During Routine Vaccine Manufacture’, JAMA, vol. 256, no. 7, pp. 869–872, Aug. 1986. [CrossRef]

- S. CE et al., ‘Yeast-recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Efficacy with hepatitis B immune globulin in prevention of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission’, JAMA, vol. 257, no. 19, pp. 2612–2616, May 1987. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Krieg, ‘CpG Motifs in Bacterial DNA and Their Immune Effects’, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 709–760. [CrossRef]

- M. Davidson and S. Krugman, ‘IMMUNOGENICITY OF RECOMBINANT YEAST HEPATITIS B VACCINE’, vol. 325, no. 8420, pp. 108–109. [CrossRef]

- W. Jilg, M. Schmidt, G. Zoulek, B. Lorbeer, B. Wilske, and F. Deinhardt, ‘CLINICAL EVALUATION OF A RECOMBINANT HEPATITIS B VACCINE’, vol. 324, no. 8413, pp. 1174–1175. [CrossRef]

- J. Pattyn, G. Hendrickx, A. Vorsters, and P. Van Damme, ‘Hepatitis B Vaccines’, J Infect Dis, vol. 224, no. Suppl 4, p. S343, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Janssen, W. L. Heyward, J. T. Martin, and R. S. Janssen, ‘Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational hepatitis B vaccine with a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) compared with a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus’, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 833–837. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Janssen et al., ‘Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational hepatitis B vaccine with a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) compared with a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in patients with chronic kidney disease’, vol. 31, no. 46, pp. 5306–5313. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Sablan et al., ‘Demonstration of safety and enhanced seroprotection against hepatitis B with investigational HBsAg-1018 ISS vaccine compared to a licensed hepatitis B vaccine’, vol. 30, no. 16, pp. 2689–2696. [CrossRef]

- C. Hristian et al., ‘Vaccinations and the Risk of Relapse in Multiple Sclerosis’. vol. 344, no. 5, pp. 319–326, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hernán, S. S. Jick, M. J. Olek, and H. Jick, ‘Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: A prospective study’, Neurology, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 838–842, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Jack, A. J. Hall, N. Maine, M. Mendy, and H. C. Whittle, ‘What level of hepatitis B antibody is protective?’, J Infect Dis, vol. 179, no. 2, pp. 489–492, 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. Poorolajal, M. Mahmoodi, R. Majdzadeh, S. Nasseri-Moghaddam, A. Haghdoost, and A. Fotouhi, ‘Long-term protection provided by hepatitis B vaccine and need for booster dose: A meta-analysis’, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 623–631. [CrossRef]

- ‘Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper – July 2017′. Accessed: Jan. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WER9227.

- W. Jilg, M. Schmidt, and F. Deinhardt, ‘Persistence of specific antibodies after hepatitis B vaccination’, J Hepatol, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 201–207, 1988. [CrossRef]

- W. Jilg, M. Schmidt, F. Deinhardt, and R. Zachoval, ‘Hepatitis B vaccination: how long does protection last?’, Lancet, vol. 2, no. 8400, p. 458, Aug. 1984. [CrossRef]

- T. Bauer and W. Jilg, ‘Hepatitis B surface antigen-specific T and B cell memory in individuals who had lost protective antibodies after hepatitis B vaccination’, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 572–577. [CrossRef]

- N. Gara et al., ‘Durability of antibody response against hepatitis B virus in healthcare workers vaccinated as adults’, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 505–513. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Meireles, R. T. Marinho, and P. Van Damme, ‘Three decades of hepatitis B control with vaccination’, World J Hepatol, vol. 7, no. 18, pp. 2127–2132, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. J. West and G. B. Calandra, ‘Vaccine induced immunologic memory for hepatitis B surface antigen: Implications for policy on booster vaccination’, Vaccine, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 1019–1027, 1996. [CrossRef]

- L. I. M. Huang, B. L. Chiang, C. Y. Lee, P. I. Lee, W. K. Chi, and M. H. Chang, ‘Long-term response to hepatitis B vaccination and response to booster in children born to mothers with hepatitis B e antigen’, Hepatology, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 954–959, 1999. [CrossRef]

- B. J. McMahon et al., ‘Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccination: results of a 15-year follow-up’, Ann Intern Med, vol. 142, no. 5, pp. 333–341, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Plotkin, E. Leuridan, and P. Van Damme, ‘Hepatitis B and the need for a booster dose’, Clin Infect Dis, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 68–75, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. J. West and G. B. Calandra, ‘Vaccine induced immunologic memory for hepatitis B surface antigen: Implications for policy on booster vaccination’, Vaccine, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 1019–1027, 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Banatvala and P. Van Damme, ‘Hepatitis B vaccine -- do we need boosters?’, J Viral Hepat, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–6, Jan. 2003. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Hall, ‘Boosters for hepatitis B vaccination? Need for an evidence-based policy’, Hepatology, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 1485–1486, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Ma et al., ‘Long-term protection at 20-31 years after primary vaccination with plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine in a Chinese rural community’, Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 16–20, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. F. Jan et al., ‘Determination of immune memory to hepatitis B vaccination through early booster response in college students’, Hepatology, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 1547–1554, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Yoshida and I. Saito, ‘Hepatitis B booster vaccination for healthcare workers’, Lancet, vol. 355, no. 9213, p. 1464, Apr. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. Banatvala, P. Van Damme, and J. Van Hattum, ‘Boosters for hepatitis B’, Lancet, vol. 356, no. 9226, pp. 337–338, 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Purdy, ‘Hepatitis B virus S gene escape mutants’, Asian J Transfus Sci, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 62, 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. F. Carman et al., ‘Vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus’, Lancet, vol. 336, no. 8711, pp. 325–329, Aug. 1990. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Hsu, M. H. Chang, Y. H. Ni, and H. L. Chen, ‘Survey of hepatitis B surface variant infection in children 15 years after a nationwide vaccination programme in Taiwan’, Gut, vol. 53, no. 10, pp. 1499–1503, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- T. Kalinina, A. Iwanski, H. Will, and M. Sterneck, ‘Deficiency in Virion Secretion and Decreased Stability of the Hepatitis B Virus Immune Escape Mutant G145R’, Hepatology, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1274–1281, 2003. [CrossRef]

- .A. Mele et al., ‘Effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination in babies born to hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers in Italy’, J Infect Dis, vol. 184, no. 7, pp. 905–908, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Chen, ‘Hepatitis B vaccination: The key towards elimination and eradication of hepatitis B’, J Hepatol, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 805–816, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Ogata et al., ‘Licensed recombinant hepatitis B vaccines protect chimpanzees against infection with the prototype surface gene mutant of hepatitis B virus’, Hepatology, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 779–786, 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Wieland, ‘The Chimpanzee Model for Hepatitis B Virus Infection’, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 1–19, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Kuo and R. Gish, ‘Chronic Hepatitis B Infection’, Clin Liver Dis, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 347–369, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Inoue and Y. Tanaka, ‘Cross-Protection of Hepatitis B Vaccination among Different Genotypes’, Vaccines 2020, Vol. 8, Page 456, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 456, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Stramer et al., ‘Nucleic Acid Testing to Detect HBV Infection in Blood Donors’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 364, no. 3, pp. 236–247, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Li, Y. Fu, J.-P. Allain, and C. Li, ‘Chronic and occult hepatitis B virus infections in the vaccinated Chinese population’, Ann Blood, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 4–4, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Zhu, X. Li, J. Li, and Z. H. Zhang, ‘Genetic variation of occult hepatitis B virus infection’, World J Gastroenterol, vol. 22, no. 13, p. 3531, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Mu, Y. M. Lin, G. M. Jow, and B. F. Chen, ‘Occult hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis B vaccinated children in Taiwan’, J Hepatol, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 264–272, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Ni et al., ‘Two Decades of Universal Hepatitis B Vaccination in Taiwan: Impact and Implication for Future Strategies’, Gastroenterology, vol. 132, no. 4, pp. 1287–1293, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang et al., ‘Factors influencing immunologic response to hepatitis B vaccine in adults’, vol. 6, p. 27251. [CrossRef]

- ‘Hepatitis B Foundation: Vaccine Non-Responders’. Accessed: Jan. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.hepb.org/prevention-and-diagnosis/vaccination/vaccine-non-responders/.

- G. Corrao et al., ‘Immune response to anti-HBV vaccination: Study of conditioning factors’, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 492–496. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Fisman, D. Agrawal, and K. Leder, ‘The Effect of Age on Immunologic Response to Recombinant Hepatitis B Vaccine: A Meta-analysis’, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 1368–1375. [CrossRef]

- O. Launay, ‘Safety and Immunogenicity of 4 Intramuscular Double Doses and 4 Intradermal Low Doses vs Standard Hepatitis B Vaccine Regimen in Adults With HIV-1′, vol. 305, no. 14, p. 1432. [CrossRef]

- Th. F. Senden, ‘Response to intradermal hepatitis B vaccination: differences between males and females?’, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 612–613. [CrossRef]

- F. E. Shaw et al., ‘Effect of anatomic injection site, age and smoking on the immune response to hepatitis B vaccination’, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 425–430. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Tedaldi et al., ‘Hepatitis A and B Vaccination Practices for Ambulatory Patients Infected with HIV’, vol. 38, no. 10, pp. 1478–1484. [CrossRef]

- H. Van Loveren et al., ‘Vaccine-induced antibody responses as parameters of the influence of endogenous and environmental factors’, vol. 109, no. 8, pp. 757–764. [CrossRef]

- WINTER, E. FOLLETT, J. MCINTYRE, J. STEWART, and I. SYMINGTON, ‘Influence of smoking on immunological responses to hepatitis B vaccine’, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 771–772. [CrossRef]

- F. Denis et al., ‘Hepatitis-B vaccination in the elderly’, J Infect Dis, vol. 149, no. 6, p. 1019, 1984. [CrossRef]

- S. de Rave, R. A. Heijtink, M. Bakker-Bendik, J. Boot, and S. W. Schalm, ‘Immunogenicity of standard and low dose vaccination using yeast-derived recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen in elderly volunteers’, Vaccine, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 532–534, 1994. [CrossRef]

- C. A. M. McNulty, J. K. Bowen, and A. J. Williams, ‘Hepatitis B vaccination in predialysis chronic renal failure patients a comparison of two vaccination schedules’, Vaccine, vol. 23, no. 32, pp. 4142–4147, Jul. 2005. [CrossRef]

- G. DaRoza et al., ‘Stage of Chronic Kidney Disease Predicts Seroconversion after Hepatitis B Immunization: Earlier is Better’, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1184–1192, 2003. [CrossRef]

- A. A. De Mattos, E. B. Gomes, C. V. Tovo, C. O. P. Alexandre, and J. O. D. R. Remião, ‘Hepatitis B vaccine efficacy in patients with chronic liver disease by hepatitis C virus’, Arq Gastroenterol, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 180–184, 2004. [CrossRef]

- I. Gutierrez Domingo et al., ‘Response to vaccination against hepatitis B virus with a schedule of four 40-μg doses in cirrhotic patients evaluated for liver transplantation: factors associated with a response’, Transplant Proc, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 1499–1501, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. T. Overton, S. Sungkanuparph, W. G. Powderly, W. Seyfried, R. K. Groger, and J. A. Aberg, ‘Undetectable plasma HIV RNA load predicts success after hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected persons’, Clin Infect Dis, vol. 41, no. 7, pp. 1045–1048, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. G. Rubin et al., ‘2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 309–318, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Cruciani et al., ‘Serologic response to hepatitis B vaccine with high dose and increasing number of injections in HIV infected adult patients’, Vaccine, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 17–22, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. Fabrizi, V. Dixit, P. Messa, and P. Martin, ‘Hepatitis B virus vaccine in chronic kidney disease: Improved immunogenicity by adjuvants? A meta-analysis of randomized trials’, vol. 30, no. 13, pp. 2295–2300. [CrossRef]

- S. Walayat, Z. Ahmed, D. Martin, S. Puli, M. Cashman, and S. Dhillon, ‘Recent advances in vaccination of non-responders to standard dose hepatitis B virus vaccine’, vol. 7, no. 24, pp. 2503–2509. [CrossRef]

- T. Vesikari et al., ‘Immunogenicity and Safety of a 3-Antigen Hepatitis B Vaccine vs a Single-Antigen Hepatitis B Vaccine: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial’, vol. 4, no. 10, pp. e2128652–e2128652. [CrossRef]

- Aggeletopoulou, P. Davoulou, C. Konstantakis, K. Thomopoulos, and C. Triantos, ‘Response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with liver cirrhosis’, vol. 27, no. 6. [CrossRef]

- M. Filippelli et al., ‘Hepatitis B vaccine by intradermal route in non responder patients: An update’, World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 20, no. 30, p. 10383, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Mahmood et al., ‘HBV Vaccines: Advances and Development’, Vaccines (Basel), vol. 11, no. 12, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Prüss-Üstün, E. Rapiti, and Y. Hutin, ‘Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers’, vol. 48, no. 6, pp. 482–490. [CrossRef]

- V. Batra, A. Goswami, S. Dadhich, D. Kothari, and N. Bhargava, ‘Hepatitis B immunization in healthcare workers’, Annals of Gastroenterology : Quarterly Publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, vol. 28, no. 2, p. 276, 2015, Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC4367220/.

- H. S. Chahal, M. G. Peters, A. M. Harris, D. McCabe, P. Volberding, and J. G. Kahn, ‘Cost-effectiveness of Hepatitis B Virus Infection Screening and Treatment or Vaccination in 6 High-risk Populations in the United States’, Open Forum Infect Dis, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Mokhtari, M. Barouni, M. Moghadami, J. Hassanzadeh, R. S. Dewey, and A. Mirahmadizadeh, ‘Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of universal hepatitis B virus vaccination in Iran: a Markov model analysis’, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1825–1833. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. Lu, S. M. McGhee, X. Xie, J. Cheng, and R. Fielding, ‘Economic evaluation of universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination in China’, vol. 31, no. 14, pp. 1864–1869. [CrossRef]

- G. Woo et al., ‘Health state utilities and quality of life in patients with hepatitis B’, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 445–451. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Siddiqui, N. Gay, W. J. Edmunds, and M. Ramsay, ‘Economic evaluation of infant and adolescent hepatitis B vaccination in the UK’, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 466–475. [CrossRef]

- S. Vijayalakshmi and A. Upadhyay, ‘Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning for Healthcare’, pp. 181–202. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Maini and L. J. Pallett, ‘Defective T-cell immunity in hepatitis B virus infection: why therapeutic vaccination needs a helping hand’, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 192–202. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Burton et al., ‘Circulating and intrahepatic antiviral B cells are defective in hepatitis B’, vol. 128, no. 10, pp. 4588–4603. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Horng et al., ‘HBV X protein-based therapeutic vaccine accelerates viral antigen clearance by mobilizing monocyte infiltration into the liver in HBV carrier mice’, vol. 27, no. 1, p. 70. [CrossRef]

- J. Zheng et al., ‘In Silico Analysis of Epitope-Based Vaccine Candidates against Hepatitis B Virus Polymerase Protein’, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 112. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Alter et al., ‘The Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis B in the United States: Need for Alternative Vaccination Strategies’, JAMA, vol. 263, no. 9, pp. 1218–1222, Mar. 1990. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Arevalo and A. E. Washington, ‘Cost-effectiveness of Prenatal Screening and Immunization for Hepatitis B Virus’, JAMA, vol. 259, no. 3, pp. 365–369, Jan. 1988. [CrossRef]

- P. Van Damme, A. Meheus, and M. Kane, ‘Integration of hepatitis B vaccination into national immunisation programmes. Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board’, BMJ, vol. 314, no. 7086, p. 1033, Apr. 1997. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Chen et al., ‘A Mass Vaccination Program in Taiwan Against Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Infants of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen—Carrier Mothers’, JAMA, vol. 257, no. 19, pp. 2597–2603, May 1987. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ruff et al., ‘Lombok Hepatitis B Model Immunization Project: toward universal infant hepatitis B immunization in Indonesia’, J Infect Dis, vol. 171, no. 2, pp. 290–296, 1995. [CrossRef]

- M. Fortuin et al., ‘Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in the Gambian expanded programme on immunisation’, The Lancet, vol. 341, no. 8853, pp. 1129–1132, May 1993. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Acharya, ‘Does the level of hepatitis B virus vaccination in health-care workers need improvement?’, J Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 1628–31, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Crosnier et al., ‘RANDOMISED PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIAL OF HEPATITIS B SURFACE ANTIGEN VACCINE IN FRENCH HAEMODIALYSIS UNITS: II, HAEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS’, The Lancet, vol. 317, no. 8224, pp. 797–800, Apr. 1981. [CrossRef]

- W. Szmuness et al., ‘Hepatitis B Vaccine in Medical Staff of Hemodialysis Units: Efficacy and Subtype Cross-Protection’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 307, no. 24, pp. 1481–1486, Dec. 1982. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Stevens, H. J. Alter, P. E. Taylor, E. A. Zang, E. J. Harley, and W. Szmuness, ‘Hepatitis B Vaccine in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis: Immunogenicity and Efficacy’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 311, no. 8, pp. 496–501, Aug. 1984. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Ma, D. Y. H. Yap, T. P. S. Yip, I. F. N. Hung, S. C. W. Tang, and T. M. Chan, ‘Vaccination in patients with chronic kidney disease—Review of current recommendations and recent advances’, Nephrology, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 5–11, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Fabrizi, R. Cerutti, V. Dixit, and E. Ridruejo, ‘Hepatitis B virus vaccine and chronic kidney disease. The advances’, Nefrologia, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 115–122, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Faser et al., ‘Increasing serum creatinine and age reduce the response to hepatitis B vaccine in renal failure patients’, J Hepatol, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 450–454, 1994. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Grzegorzewska, ‘Hepatitis B Vaccination in Chronic Kidney Disease: Review of Evidence in Non-Dialyzed Patients’, Hepat Mon, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 7359, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. DaRoza et al., ‘Stage of Chronic Kidney Disease Predicts Seroconversion after Hepatitis B Immunization: Earlier is Better’, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1184–1192, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. Y. Ong, H. Y. Wong, and G. Y. Khee, ‘What is the hepatitis B vaccination regimen in chronic kidney disease?’, Cleve Clin J Med, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 32–34, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Udomkarnjananun et al., ‘Hepatitis B virus vaccine immune response and mortality in dialysis patients: a meta-analysis’, J Nephrol, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 343–354, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Kovacic, M. Sain, and V. Vukman, ‘Efficient haemodialysis improves the response to hepatitis B virus vaccination’, Intervirology, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 172–176, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- A. Asan et al., ‘Factors affecting responsiveness to hepatitis B immunization in dialysis patients’, Int Urol Nephrol, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 1845–1850, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ayub, M. R. Bacci, F. L. A. Fonseca, and E. Z. Chehter, ‘Hemodialysis and hepatitis B vaccination: a challenge to physicians’, Int J Gen Med, vol. 7, pp. 109–114, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Benhamou et al., ‘Hepatitis B vaccine: Randomized trial of immunogenicity in hemodialysis patients’, Clin Nephrol, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 143–147, Jan. 1984.

- K. Bel’eed, M. Wright, D. Eadington, M. Farr, and L. Sellars, ‘Vaccination against hepatitis B infection in patients with end stage renal disease’, Postgrad Med J, vol. 78, no. 923, pp. 538–540, Sep. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Somi and B. Hajipour, ‘Improving Hepatitis B Vaccine Efficacy in End-Stage Renal Diseases Patients and Role of Adjuvants’, ISRN Gastroenterol, vol. 2012, pp. 1–9, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Friedrich, A. Sattler, K. Müller, M. Nienen, P. Reinke, and N. Babel, ‘Comparing Humoral and Cellular Immune Response Against HBV Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Patients’, American Journal of Transplantation, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 3157–3165, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Ma, D. Y. H. Yap, T. P. S. Yip, I. F. N. Hung, S. C. W. Tang, and T. M. Chan, ‘Vaccination in patients with chronic kidney disease—Review of current recommendations and recent advances’, Nephrology, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 5–11, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Marinaki, K. Kolovou, S. Sakellariou, J. N. Boletis, and I. K. Delladetsima, ‘Hepatitis B in renal transplant patients’, World J Hepatol, vol. 9, no. 25, p. 1054, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Eleftheriadis, G. Pissas, G. Antoniadi, V. Liakopoulos, and I. Stefanidis, ‘Factors affecting effectiveness of vaccination against hepatitis B virus in hemodialysis patients’, World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 20, no. 34, p. 12018, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Lefebure, G. A. Verpooten, M. M. Couttenye, and M. E. De Broe, ‘Immunogenicity of a recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine in renal transplant patients’, Vaccine, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 397–399, Jan. 1993. [CrossRef]

- F. Fabrizi, P. Martin, V. Dixit, S. Bunnapradist, and G. Dulai, ‘Meta-analysis: The effect of age on immunological response to hepatitis B vaccine in end-stage renal disease’, Aliment Pharmacol Ther, vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 1053–1062, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. Goilav and P. Piot, ‘Vaccination against hepatitis B in homosexual men: A review’, Am J Med, vol. 87, no. 3, pp. S21–S25, Sep. 1989. [CrossRef]

- W. Szmuness et al., ‘Hepatitis B Vaccine: Demonstration of Efficacy in a Controlled Clinical Trial in a High-Risk Population in the United States’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 303, no. 15, pp. 833–841, Oct. 1980. [CrossRef]

- N. Odaka et al., ‘Comparative Immunogenicity of Plasma and Recombinant Hepatitis B Virus Vaccines in Homosexual Men’, JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 260, no. 24, pp. 3635–3637, Dec. 1988. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Francis et al., ‘The prevention of hepatitis B with vaccine. Report of the centers for disease control multi-center efficacy trial among homosexual men’, Ann Intern Med, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 362–366, Jan. 1982. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Francis et al., ‘The prevention of hepatitis B with vaccine. Report of the centers for disease control multi-center efficacy trial among homosexual men’, Ann Intern Med, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 362–366, Jan. 1982. [CrossRef]

- R. Vet, J. B. F. de Wit, and E. Das, ‘Factors associated with hepatitis B vaccination among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of published research’. vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 534–542, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Haban et al., ‘Assessment of the HBV vaccine response in a group of HIV-infected children in Morocco’, BMC Public Health, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–6, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. X. Catherine and L. Piroth, ‘Hepatitis B virus vaccination in HIV-infected people: A review’, Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1304, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Pippi et al., ‘Serological response to hepatitis B virus vaccine in HIV-infected children in Tanzania’, HIV Med, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 519–525, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Zuin et al., ‘Impaired response to hepatitis B vaccine in HIV infected children’, Vaccine, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 857–860, Jan. 1992. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Laurence, ‘Hepatitis A and B immunizations of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus’, Am J Med, vol. 118, no. 10, pp. 75–83, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Paitoonpong and C. Suankratay, ‘Immunological response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with AIDS and virological response to highly active antiretroviral therapy’, Scand J Infect Dis, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 54–58, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Rech-Medeiros, P. dos S. Marcon, C. do V. Tovo, and A. A. de Mattos, ‘Evaluation of response to hepatitis B virus vaccine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus’, Ann Hepatol, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 725–729, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Mohareb and A. Y. Kim, ‘Hepatitis B Vaccination in People Living With HIV—If at First You Don’t Succeed, Try Again’, JAMA Netw Open, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. e2121281–e2121281, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, J. Loucks, and M. Shah, ‘Efficacy of Hepatitis B Vaccine in Adults with Chronic Liver Disease’. vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 839–844, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Roni, R. M. Pathapati, A. S. Kumar, L. Nihal, K. Sridhar, and S. Tumkur Rajashekar, ‘Safety and efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination in cirrhosis of liver’, Adv Virol, vol. 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Reiss and E. B. Keeffe, ‘Hepatitis vaccination in patients with chronic liver disease’, Aliment Pharmacol Ther, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 715–727, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. Horta et al., ‘Efficacy of Hepatitis B Virus Vaccines HBVaxpro40© and Fendrix© in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease in Clinical Practice’, Vaccines 2022, Vol. 10, Page 1323, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 1323, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Hassnine et al., ‘Clinical study on the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination in hepatitis C virus related chronic liver diseases in Egypt’, Virus Res, vol. 323, p. 198953, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Mendenhall et al., ‘Hepatitis B vaccination - Response of alcoholic with and without liver injury’, Dig Dis Sci, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 263–269, Mar. 1988. [CrossRef]

- F. Degos et al., ‘Hepatitis B vaccination in chronic alcoholics’, J Hepatol, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 402–409, Jan. 1986. [CrossRef]

- G. Reiss and E. B. Keeffe, ‘Hepatitis vaccination in patients with chronic liver disease’, Aliment Pharmacol Ther, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 715–727, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- I. Fernández, J. M. Pascasio, and J. Colmenero, ‘Prophylaxis and treatment in liver transplantation. VII Consensus Document of the Spanish Society of Liver Transplantation’, Gastroenterología y Hepatología (English Edition), vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 169–177, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Takaki, T. Yasunaka, and T. Yagi, ‘Molecular Mechanisms to Control Post-Transplantation Hepatitis B Recurrence’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, Vol. 16, Pages 17494-17513, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 17494–17513, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Nasir and G. Y. Wu, ‘Prevention of HBV Recurrence after Liver Transplant: A Review’, J Clin Transl Hepatol, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 150, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Jiménez-Pérez, R. González-Grande, J. Mostazo Torres, C. González Arjona, and F. J. Rando-Muñoz, ‘Management of hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation’, World J Gastroenterol, vol. 21, no. 42, p. 12083, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ishigami et al., ‘Frequent incidence of escape mutants after successful hepatitis B vaccine response and stopping of nucleos(t)ide analogues in liver transplant recipients’, Liver Transplantation, vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 1211–1220, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Jo, J. F. Khan, J. H. Han, Y. D. Yu, and D. S. Kim, ‘Efficacy and Safety of Hepatitis B Virus Vaccination Following Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin Withdrawal After Liver Transplantation’, Transplant Proc, vol. 53, no. 10, pp. 3016–3021, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. C. Rodrigues, R. C. M. A. De Da Silva, H. C. C. De Felício, and R. F. Da Silva, ‘NEW IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULE EFFECTIVENESS AGAINST HEPATITIS B IN LIVER TRANSPLANTATION PATIENTS’, Arq Gastroenterol, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 440–446, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Saab, P. yu Chen, C. E. Saab, and M. J. Tong, ‘The Management of Hepatitis B in Liver Transplant Recipients’, Clin Liver Dis, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 721–736, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- ‘Global hepatitis report, 2017′. Accessed: Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455.

- D. Razavi-Shearer and H. Razavi, ‘Global prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and prevention of mother-to-child transmission – Authors’ reply’, vol. 3, no. 9, p. 599. [CrossRef]

- S. Shan and J. Jia, ‘Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus in the Western Pacific Region’, Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken), vol. 18, no. 1, p. 18, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. -H Chang, D. -S Chen, H. -C Hsu, H. -Y Hsu, and C. -Y Lee, ‘Maternal transmission of hepatitis B virus in childhood hepatocellular carcinoma’, Cancer, vol. 64, no. 11, pp. 2377–2380, Dec. 1989. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Stevens et al., ‘Eradicating hepatitis B virus: The critical role of preventing perinatal transmission’, Biologicals, vol. 50, pp. 3–19, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Assateerawatt, V. S. Tanphaichitr, V. Suvatte, and S. Yodthong, ‘Immunogenicity and efficacy of a recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine, GenHevac B Pasteur in high risk neonates, school children and healthy adults’, Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 85–91, Jan. 1993.

- Y. Poovorawan, S. Sanpavat, W. Pongpunlert, S. Chumdermpadetsuk, P. Sentrakul, and A. Safary, ‘Protective Efficacy of a Recombinant DNA Hepatitis B Vaccine in Neonates of HBe Antigen—Positive Mothers’, JAMA, vol. 261, no. 22, pp. 3278–3281, Jun. 1989. [CrossRef]

- A. Milne, D. J. West, D. Van Chinh, C. D. Moyes, and G. Poerschke, ‘Field evaluation of the efficacy and immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine without HBIG in newborn Vietnamese infants’, J Med Virol, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 327–333, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. X. T. Tan et al., ‘Serologic Responses after Hepatitis B Vaccination in Preterm Infants Born to Hepatitis B Surface Antigen-Positive Mothers: Singapore Experience’, Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. e208–e210, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang et al., ‘Efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccine alone in the prevention of hepatitis B perinatal transmission in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen-negative carrier mothers’, J Virus Erad, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 100076, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Assateerawatt, V. S. Tanphaichitr, V. Suvatte, and S. Yodthong, ‘Immunogenicity and efficacy of a recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine, GenHevac B Pasteur in high risk neonates, school children and healthy adults’, Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 85–91, Jan. 1993.

- Y. Poovorawan et al., ‘Impact of hepatitis B immunisation as part of the EPI’, Vaccine, vol. 19, no. 7–8, pp. 943–949, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Stevens, P. T. Toy, P. E. Taylor, T. Lee, and H. Y. Yip, ‘Prospects for Control of Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Implications of Childhood Vaccination and Long-term Protection’, Pediatrics, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 170–173, Jul. 1992. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Hsu et al., ‘Efficacy of a Mass Hepatitis B Vaccination Program in Taiwan: Studies on 3464 Infants of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen—Carrier Mothers’, JAMA, vol. 260, no. 15, pp. 2231–2235, Oct. 1988. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Burk, L. Y. Hwang, G. Y. F. Ho, D. A. Shafritz, and R. P. Beasley, ‘Outcome of perinatal hepatitis b virus exposure is dependent on maternal virus load’, Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 170, no. 6, pp. 1418–1423, Dec. 1994. [CrossRef]

- M. Belopolskaya, V. Avrutin, S. Firsov, and A. Yakovlev, ‘HBsAg level and hepatitis B viral load correlation with focus on pregnancy’, Annals of Gastroenterology : Quarterly Publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, vol. 28, no. 3, p. 379, 2015, Accessed: Jan. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC4480176/.

- W. H. Wen et al., ‘Quantitative maternal hepatitis B surface antigen predicts maternally transmitted hepatitis B virus infection’, Hepatology, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 1451–1461, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. X. Sun et al., ‘A predictive value of quantitative HBsAg for serum HBV DNA level among HBeAg-positive pregnant women’, Vaccine, vol. 30, no. 36, pp. 5335–5340, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Lampertico et al., ‘EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection’, J Hepatol, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 370–398, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Q. Pan et al., ‘Tenofovir to Prevent Hepatitis B Transmission in Mothers with High Viral Load’, N Engl J Med, vol. 374, no. 24, pp. 2324–2334, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Alter et al., ‘The Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis B in the United States: Need for Alternative Vaccination Strategies’, JAMA, vol. 263, no. 9, pp. 1218–1222, Mar. 1990. [CrossRef]

- P. Van Damme, A. Meheus, and M. Kane, ‘Integration of hepatitis B vaccination into national immunisation programmes’, BMJ, vol. 314, no. 7086, p. 1033, Apr. 1997. [CrossRef]

- ‘Hepatitis B is preventable with safe and effective vaccines’. Accessed: Jan. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/activities/hepatitis-b-is-preventable-with-safe-and-effective-vaccines.

- M. H. Chang and D. S. Chen, ‘Prevention of Hepatitis B’, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 5, no. 3, 2015. [CrossRef]

- ‘Immunization coverage’. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage.

- Z. Liu et al., ‘Impact of the national hepatitis B immunization program in China: a modeling study’, Infect Dis Poverty, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Wait and D. S. Chen, ‘Towards the eradication of hepatitis B in Taiwan’, Kaohsiung J Med Sci, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Chiang, Y. W. Yang, S. L. You, M. S. Lai, and C. J. Chen, ‘Thirty-Year Outcomes of the National Hepatitis B Immunization Program in Taiwan’, JAMA, vol. 310, no. 9, pp. 974–976, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Ni, M. H. Chang, J. F. Wu, H. Y. Hsu, H. L. Chen, and D. S. Chen, ‘Minimization of hepatitis B infection by a 25-year universal vaccination program’, J Hepatol, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 730–735, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Hsu, C. F. Lu, S. C. Lee, S. R. Lin, and D. S. Chen, ‘Seroepidemiologic survey for hepatitis B virus infection in Taiwan: The effect of hepatitis B mass immunization’, Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 179, no. 2, pp. 367–370, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Hsu, C. F. Lu, S. C. Lee, S. R. Lin, and D. S. Chen, ‘Seroepidemiologic survey for hepatitis B virus infection in Taiwan: The effect of hepatitis B mass immunization’, Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 179, no. 2, pp. 367–370, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. Moghadami, N. Dadashpour, A. M. Mokhtari, M. Ebrahimi, and A. Mirahmadizadeh, ‘The effectiveness of the national hepatitis B vaccination program 25 years after its introduction in Iran: a historical cohort study’, Braz J Infect Dis, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 419–426, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Childs, S. Roesel, and R. A. Tohme, ‘Status and progress of hepatitis B control through vaccination in the South-East Asia Region, 1992–2015′, Vaccine, vol. 36, no. 1, p. 6, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Chang, ‘Hepatitis B virus infection’, Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 160–167, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Lolekha, B. Warachit, A. Hirunyachote, P. Bowonkiratikachorn, D. J. West, and G. Poerschke, ‘Protective efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine without HBIG in infants of HBeAg-positive carrier mothers in Thailand’, Vaccine, vol. 20, no. 31, pp. 3739–3743, Nov. 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. X. T. Tan et al., ‘Serologic Responses after Hepatitis B Vaccination in Preterm Infants Born to Hepatitis B Surface Antigen-Positive Mothers: Singapore Experience’, Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. e208–e210, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. P. Nelson, P. J. Easterbrook, and B. J. McMahon, ‘Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Impact of Vaccination on Disease’, Clin Liver Dis, vol. 20, no. 4, p. 607, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- ‘Pinkbook: Hepatitis B | CDC’. Accessed: Jan. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hepb.html.

- J. H. Kao, H. M. Hsu, W. Y. Shau, M. H. Chang, and D. S. Chen, ‘Universal hepatitis B vaccination and the decreased mortality from fulminant hepatitis in infants in Taiwan’, J Pediatr, vol. 139, no. 3, pp. 349–352, Sep. 2001. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Chen et al., ‘Pediatric fulminant hepatic failure in endemic areas of hepatitis B infection: 15 years after universal hepatitis B vaccination’, Hepatology, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 58–63, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. Mele et al., ‘Acute hepatitis B 14 years after the implementation of universal vaccination in Italy: Areas of improvement and emerging challenges’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 868–875, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Mele et al., ‘Acute hepatitis delta virus infection in Italy: incidence and risk factors after the introduction of the universal anti-hepatitis B vaccination campaign.’, Clin Infect Dis, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. e17–e24, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Goh, ‘Prevention and control of hepatitis B virus infection in Singapore.’, Ann Acad Med Singap, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 671–681, Sep. 1997, Accessed: Jan. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://europepmc.org/article/med/9494677.

- R. Bhimma, H. M. Coovadia, M. Adhikari, and C. A. Connolly, ‘The impact of the hepatitis B virus vaccine on the incidence of hepatitis B virus-associated membranous nephropathy’, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, vol. 157, no. 10, pp. 1025–1030, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu, L. Sun, L. J. Zhou, L. J. Fang, F. Y. Sheng, and Y. Q. Guo, ‘The effect of hepatitis B vaccination on the incidence of childhood HBV-associated nephritis’, Pediatric Nephrology, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1216–1219, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Liao, M. H. Chang, F. G. Lin, I. J. Tsai, Y. W. Chang, and Y. K. Tsau, ‘Universal Hepatitis B Vaccination Reduces Childhood Hepatitis B Virus–Associated Membranous Nephropathy’, Pediatrics, vol. 128, no. 3, pp. e600–e604, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. -H Chang, D. -S Chen, H. -C Hsu, H. -Y Hsu, and C. -Y Lee, ‘Maternal transmission of hepatitis B virus in childhood hepatocellular carcinoma’, Cancer, vol. 64, no. 11, pp. 2377–2380, Dec. 1989. [CrossRef]

- M.-H. Chang et al., ‘Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group’, N Engl J Med, vol. 336, no. 26, pp. 1855–1859, Jun. 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Yu et al., ‘Accelerating Decreases in the Incidences of Hepatocellular Carcinoma at a Younger Age in Shanghai Are Associated With Hepatitis B Virus Vaccination’, Front Oncol, vol. 12, p. 855945, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Flores, A. J. Thompson, M. Ryan, and J. Howell, ‘The Global Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination on Hepatocellular Carcinoma’, Vaccines (Basel), vol. 10, no. 5, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Madani, ‘Trend in incidence of hepatitis B virus infection during a decade of universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination in Saudi Arabia’, Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 278–283, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. cheng Li et al., ‘Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination on hepatitis B prevention and on hepatocellular carcinoma’, Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 385–387, May 2004.

- M. S. Lee et al., ‘Hepatitis B vaccination and reduced risk of primary liver cancer among male adults: A cohort study in Korea’, Int J Epidemiol, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 316–319, Apr. 1998. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Meireles, R. T. Marinho, and P. Van Damme, ‘Three decades of hepatitis B control with vaccination’, World J Hepatol, vol. 7, no. 18, p. 2127, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Sheena et al., ‘Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019′, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 796–829, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Schweitzer, M. K. Akmatov, and G. Krause, ‘Hepatitis B vaccination timing: results from demographic health surveys in 47 countries’, Bull World Health Organ, vol. 95, no. 3, p. 199, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- ‘Vaccine Introduction and Coverage in Gavi-Supported Countries 2015-2018: Implications for Gavi 5.0 | Center For Global Development’. Accessed: Jan. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/vaccine-introduction-and-coverage-gavi-supported-countries-2015-2018-implications-gavi.

- J. BIGHAM, ‘Implementing and Understanding Barriers to the Updated Hepatitis B Vaccination Recommendations and Guidance’, Fam Pract Manag, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 29–32, Sep. 2023, Accessed: Jan. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://localhost:4503/content/brand/aafp/pubs/fpm/issues/2023/0900/hepatitis-b-vaccination-barriers.html.

- P. B. Machmud, A. Führer, C. Gottschick, and R. Mikolajczyk, ‘Barriers to and Facilitators of Hepatitis B Vaccination among the Adult Population in Indonesia: A Mixed Methods Study’, Vaccines (Basel), vol. 11, no. 2, p. 398, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Freeland et al., ‘Barriers and facilitators to hepatitis B birth dose vaccination: Perspectives from healthcare providers and pregnant women accessing antenatal care in Nigeria’, PLOS Global Public Health, vol. 3, no. 6, p. e0001332, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Mohanty, P. Jena, and L. Patnaik, ‘Vaccination against Hepatitis B: A Scoping Review’, Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 3453–3459, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Ali, N. A. Hussein, E. O. H. Elmi, A. M. Ismail, and M. M. Abdi, ‘Hepatitis B vaccination coverage and associated factors among medical students: a cross-sectional study in Bosaso, Somalia, 2021′, BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Smith et al., ‘Global progress on the elimination of viral hepatitis as a major public health threat: An analysis of WHO Member State responses 2017′, JHEP Rep, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 81–89, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Vogel, T. Meyer, G. Sapisochin, R. Salem, and A. Saborowski, ‘Hepatocellular carcinoma’, The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10360, pp. 1345–1362, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- ‘Hepatitis B’. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

- ‘The Global Hepatitis Health Sector Strategy – Global Targets’, 2017, Accessed: Jan. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442270/.

- D. L. Thomas, ‘Global Elimination of Chronic Hepatitis’, N Engl J Med, vol. 380, no. 21, pp. 2041–2050, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Cooke et al., ‘Accelerating the elimination of viral hepatitis: a Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 135–184, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, W. Liang, W. Jing, and M. Liu, ‘Countdown to 2030: eliminating hepatitis B disease, China’, Bull World Health Organ, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 230–238, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Razavi-Shearer et al., ‘Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 383–403, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Nayagam, Y. Shimakawa, and M. Lemoine, ‘Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B: What more needs to be done to eliminate it around the world?’, J Viral Hepat, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 342–349, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Schröeder et al., ‘Innovative strategies for the elimination of viral hepatitis at a national level: A country case series’, Liver Int, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 1818–1836, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Tordrup et al., ‘Additional resource needs for viral hepatitis elimination through universal health coverage: projections in 67 low-income and middle-income countries, 2016-30′, Lancet Glob Health, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. e1180–e1188, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Razavi, Y. Sanchez Gonzalez, C. Yuen, and M. Cornberg, ‘Global timing of hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries’, Liver Int, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 522–529, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Palayew, H. Razavi, S. J. Hutchinson, G. S. Cooke, and J. V. Lazarus, ‘Do the most heavily burdened countries have the right policies to eliminate viral hepatitis B and C?’, Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 948–953, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Kondili et al., ‘Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis B and C elimination: An EASL survey’, JHEP Reports, vol. 4, no. 9, p. 100531, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Blach et al., ‘Impact of COVID-19 on global HCV elimination efforts’, J Hepatol, vol. 74, no. 1, p. 31, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Sowah and C. Chiou, ‘Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on Viral Hepatitis Elimination: What Is the Price?’, AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, vol. 37, no. 8, p. 585, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Laury, L. Hiebert, and J. W. Ward, ‘Impact of COVID-19 Response on Hepatitis Prevention Care and Treatment: Results From Global Survey of Providers and Program Managers’, Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken), vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 41–46, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Bertram and T. T. T. Edejer, ‘Introduction to the Special Issue on “The World Health Organization Choosing Interventions That Are Cost-Effective (WHO-CHOICE) Update”’, Int J Health Policy Manag, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 670–672, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- ‘Consolidated strategic information guidelines for viral hepatitis planning and tracking progress towards elimination: guidelines’. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515191.

- ‘New cost-effectiveness updates from WHO-CHOICE’. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/new-cost-effectiveness-updates-from-who-choice.

- ‘Hepatitis WPRO’. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/hepatitis#tab=tab_1.

- S. W. Lee et al., ‘Comparison of tenofovir and entecavir on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B in Korea: a large-scale, propensity score analysis’, Gut, vol. 69, no. 7, pp. 1301–1308, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Cornberg et al., ‘Guidance for design and endpoints of clinical trials in chronic hepatitis B - Report from the 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference’, Hepatology, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 1070–1092, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- ‘Polaris Observatory – CDA Foundation’. Accessed: Feb. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://cdafound.org/polaris/.

- ‘The Hepatitis Prevention, Control, and Elimination Program in Mongolia - Элэг бүтэн Мoнгoл үндэсний хѳтѳлбѳр (National program) | Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination’. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.globalhep.org/about/partner-programs/hepatitis-prevention-control-and-elimination-program-mongolia-eleg-buten.

- ‘Find the Missing Millions - World Hepatitis Alliance’. Accessed: Feb. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldhepatitisalliance.org/find-the-missing-millions/.

- R. Rajbhandari and R. T. Chung, ‘Screening for hepatitis B virus infection: a public health imperative’, Ann Intern Med, vol. 161, no. 1, pp. 76–77, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Abbas and M. Abbas, ‘Challenges in Formulation and Implementation of Hepatitis B Elimination Programs’, Cureus, vol. 13, no. 4, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Lemoine et al., ‘Acceptability and feasibility of a screen-and-treat programme for hepatitis B virus infection in The Gambia: the Prevention of Liver Fibrosis and Cancer in Africa (PROLIFICA) study’, Lancet Glob Health, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. e559–e567, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Lin and J. H. Kao, ‘Review article: novel therapies for hepatitis B virus cure – advances and perspectives’, Aliment Pharmacol Ther, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 213–222, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. C. Fanning, F. Zoulim, J. Hou, and A. Bertoletti, ‘Therapeutic strategies for hepatitis B virus infection: towards a cure’, Nat Rev Drug Discov, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 827–844, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Howell et al., ‘A global investment framework for the elimination of hepatitis B’, J Hepatol, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 535–549, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Chen, ‘Fighting against viral hepatitis: Lessons from Taiwan’, Hepatology, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 381–392, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

| TARGET AREA | BASELINE 2015 | 2020 TARGETS | 2030 TARGETS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact targets | |||

| Incidence: New cases of CHB and CHC infections | Between 6 and 10 million infections are reduced to 0.9 million infections by 2030 (95% decline in HBV infections, 80% decline in HCV infections) | 30% reduction (equivalent to 1% prevalence of HBsAg among children) | 90% reduction (equivalent to 0.1% prevalence of HBsAg among children) |

| Mortality: HBV and HCV deaths | 1.4 million deaths reduced to less than 500 000 by 2030 (65% for both HBV and HCV) | 10% reduction | 65% reduction |

| Service coverage targets | |||

| HBV vaccination: childhood vaccine coverage (third dose coverage) | 82% in infants | 90% | 90% |

| Prevention of HBV MTCT: HBV birth-dose vaccination coverage or other approach to prevent MTCT | 38% | 50% | 90% |

| Blood safety | 39 countries do not routinely test all blood donations for transfusion transmissible infections 89% of donations are screened in a quality-assured manner | All countries have hemovigilance systems in place to identify and quantify viral hepatitis transfusion transmission rates | Reduce rates of transmission by 99% compared with 2020. |

| Safe injections: percentage of injections administered with safety-engineered devices in and out of health facilities | 5% | 50% | 90% |

| Harm reduction: number of sterile needles and syringes provided per person who injects drugs per year | 20 | 200 | 300 |

| HBV and HCV diagnosis | <5% of chronic hepatitis infections diagnosed | 50% | 90% |

| HBV and HCV treatment | <1% receiving treatment | 5 million people receiving HBV treatment, 3 million people received HCV treatment | 80% of eligible persons with CHB infection treated 80% of eligible persons with CHC infection treated |

| Maternal screening | Infants receive | Efficacy | Cost | Example | |

| Vaccine | HBIG | ||||

| Yes (HBsAg and then HBeAg) | Yes | HBeAg-positive mothers’ infants only | Higher | Higher | Taiwan |

| Yes (HBsAg only) | Yes | All HBsAg-positive mothers’ infants | Highest | Highest | US |

| Yes (HBeAg only) | Yes | HBeAg-positive mothers’ infants only (2 doses) | High | Highest | Japan |

| No | Yes | No | Modest | Low | Thailand |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).