1. Introduction

The control of overabundant wildlife populations is of increasing concern to the public and wildlife managers for the damages caused by wild animals to vegetation, ecosystems, and automobiles (Boulanger et al., 2012).

Overabundant control in different wild species has conventionally focused on lethal removal, but this method is rejected for legal, safety and ethical concerns (Massei, 2023). Alternative methods are studied, including translocation, predator reintroduction, birth control through contraception (Malcolm et al., 2010; Warren, 2011) and surgical sterilization (MacLean et al., 2006; Merrill et al., 2006; Boulanger & Curtis, 2016). The disadvantages of translocation are costs, animals submitted to elevated stress during transports, increase of risks of disease transmission and difficulty to find other release sites (Beringer et al., 1973; Massei et al., 2010). Predator reintroduction involves security issues for negative human–predator interactions (Laundré et al., 2001; Patterson et al., 2003; Warren, 2011). Birth control might reduce and maintain some animal populations at desired levels (Hampton et al., 2015). Birth control can involve the using of drugs (temporary control) or surgical sterilization (permanent control) (Kutzler & Wood, 2006). It was reported that the contracepted drugs have limited success. Disadvantages are due to uncertainty in identifying treated individuals, need for repeated treatments, high costs and secondary consumption by nontarget animals (e.g., scavengers), (Massei et al., 2014; Warren, 2000). Malcolm et al. (2010) used an intrauterine devices that were implanted prior to the breeding season and prevented pregnancy in 6 of 8 female deer during a 2-year period. The use of porcine zona pellucida has been successfully used on female white-tailed deer (Rutberg et al., 2013) and feral horses (Bechert et al., 2013), with a reducing pregnancy rate by 45% in wild white-tailed deer (Rutberg et al., 2013). A single shot variant of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone vaccine (i.e., GonaCon™) has been used on many wildlife species including white-tailed deer ( Miller et al., 2008; Gionfriddo et al., 2009), elk (Cervus elaphus; (Powers et al., 2014), wild boar (Sus scrofa; (Quy et al., 2014), and Eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger; (Krause et al., 2014). GonaConTM inhibits the reproduction as, stimulating the animal’s immune system, it creates antibodies against the GnRH, with consequent reduction of sex hormones (Miller et al., 2008). In white-tailed deer, a single dose of GonaCon™ has been effective, in reducing pregnancies, in 67–88% of deer one year after administration, and 47–48% in the second year after administration (Gionfriddo et al., 2009, 2011).

Surgical sterilization included tubal ligation or transection, ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy in laparotomy or laparoscopy. Tubal ligation or transection prevents reproduction without altering normal hormonal function and then inducing a prolonged breeding season with prolonged mate-searching behavior (MacLean et al., 2006; Hampton et al., 2015). The ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy were widely used in different wild species, because these techniques are effective, with reduce stress and costs associated with recapture and administering doses of vaccines (Boulanger et al., 2012). Surgical technique can be performed by two approaches: flank and midventral, both used currently in large animals’ surgery (Abubakar et al., 2014). In ruminants, flank approach is the most widely and frequently practiced and it has different advantages, such as the surgical site that can be visualized and observed from a distance, it has a reduced potential risk for evisceration if occurring wound dehiscence, and the suture of the oblique muscles helps maintain the integrity of the abdominal wall (Abubakar et al., 2014). These advantages are important mainly in wild animals.

The aim of this study was to compare flank and midventral laparotomy approaches in ovariectomy of mouflons, in field condition. To compare these approaches, we evaluated the time of surgeries, intra or post-operative complications, intra-operative nociception and post-operative pain. The hypothesis of this study is that there are some differences of tested parameters in two used approaches, to choose the better surgical approach when the ovariectomy is performed in field condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethic

The protocol for animal research was approved by the Ethics Committee for animal testing–CESA of the Department of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy with approval number 20/2023.

2.2. Animals

All mouflons came from Giglio Island to the Marsiliana Nature Reserve for the project LIFE18NAT/IT/000828 LETSGO GIGLIO "Less alien species in the Tuscan Archipelago: new actions to protect Giglio island habitats". All animals were transferred about a month before surgery. The mouflons were sexually mature (18-30 months) and in good health condition (body condition score of 3), without previous pathologies, and were allocated to the very low anesthetic risk class (ASA 1). This study enrolled 20 female mouflons. The animals were randomly divided into two groups. In the first Group (F) the animals were gonadectomized using left flank as the surgical access, in the second group (A), the linea alba. For all animals the AESCULAP CAIMAN® Seal and Cut device was employed for clamping the ovary, stapling the vessels, and cutting in one stroke. For each animal, surgical times (from skin incision to the placement of the final suture), the duration of anesthesia (from induction with Propofol to the interruption of Isoflurane administration) and the time to recovery (from the interruption of Isoflurane administration to the recovery of quadrupedal station) were evaluated.

In addition, to compare the two surgical techniques, the intra-operative nociception (measured by the heart rate, respiratory rate, non-invasive blood pressure and temperature), intra- and post-operative complications, and the post-operative pain were evaluated.

2.3. Anesthetic Protocol

Food was withheld from the patients for 24 h prior to gonadectomy. The day before the procedure, the mouflons were captured in a funnel-shaped enclosure. The day of gonadectomy, the mouflons were captured from the enclosure by operators and contained for premedication (Cicirelli et al., 2023). The premedication consisted of xylazine (Nerfasin® 20 mg/mL, ATI, Ozzano dell’Emilia, Italy) 0.1 mg/kg and an association of tiletamine and zolazepam (Zoletil® 50/50 mg/mL, Virbac, Milan, Italy) 4 mg/kg, mixed in the same syringe and injected in the brachiocephalicus muscle. Intramuscular (IM) injection of 10.000 UI/kg benzilpenicilline and 12.5 mg/kg dihydrostreptomicine (Repen, Fatro S.p.A., Ozzano dell’Emilia BO, Italy; 200.000 UI + 250 mg/mL) was administered 10 min after the premedication to provide antibiotic coverage. Then, a 20-G venous catheter (DeltaVen®, DeltaMed S.p.A., Viadana, Italy) was inserted in the cephalic vein to start a maintenance fluid therapy (3 mL/kg/h of ringer with lactate, with possible variations during surgery, depending on the hemodynamic needs). Propofol (PropoVet Multidose® 10 mg/mL, Zoetis Italia S.r.l., Rome, Italy) at 2 mg/kg was loaded into the syringe and was administered intravenously to allow orotracheal intubation, and anesthetic maintenance was performed with isoflurane (Isoflo®, Zoetis Italia S.r.l., Rome, Italy), in an open anesthesia system (MedVet S.r.l., Taranto, Italy), always performed by the same operator. All patients were connected to a re-breathing respiratory circuit and were allowed to breath spontaneously. This protocol was in accordance with that described by Caulkett & Haigh, (2007). During the perioperative period, the animals were continuously monitored through multiparametric monitoring of the heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), non-invasive mean arterial blood pressure (MAP). In the event of increases in these parameters (>25% compared to the pre-incision values) during the procedure in response to the surgical pain, a bolus of fentanyl would be administered intravenously at 2 μg/kg (Fentadon®, Dechra Veterinary Products S.r.l., Torino, Italy) as rescue analgesia. In addition, were monitored oxygen hemoglobin saturation (SpO2) and body temperature (T) using pulse oximeter and thermometer to allow controlled and safe anesthesia (Cicirelli et al., 2022).

2.4. Surgical Procedure

All operations were performed by the same surgeon staff. Ten animals (group F) were gonadectomized via left flank as the surgical access (

Figure 1).

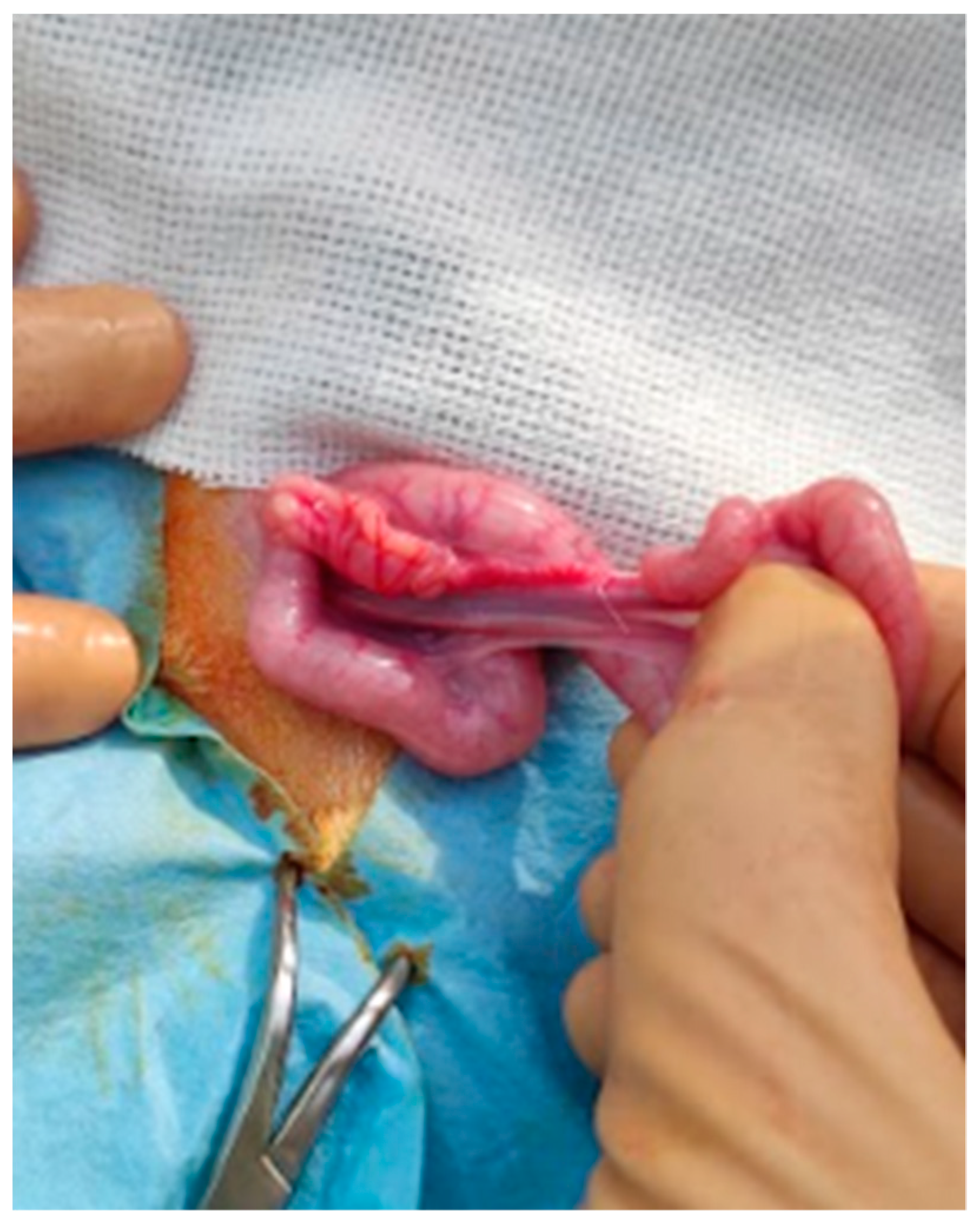

The paralumbar fossa from the transverse processes of the lumbar and sacral vertebrae and from the last rib to the level of the tuber coxae was clipped, shaved, and aseptically prepared. A vertical skin incision (about 6 cm long) with a number 23 scalpel blade was performed on the left flank on the paralumbar fossa close to the iliac wing. All muscular layers (in order, the external and internal abdominal oblique muscles and transverse muscle) were punctured with the scalpel to facilitate surgical access and then proceeded with the separation of the muscle fibers down to the peritoneum, which was held with the forceps, punctured with the scalpel, and cut with scissors. The surgeon grasped the uterus, using fingers, and exteriorized, locating the ovaries (

Figure 2).

The clamp of the CAIMAN® (CAIMAN® 5 non-articulated; Aesculap AG, Tuttlingen, Germany) vessel sealing device (handpiece 5 mm straight bite non-articulated jaw length 24 cm) was affixed to the base of the ovary, at the level of the ovarian pedicle, and then the ovariectomy was performed (

Figure 3).

Therefore, observation of any hemorrhages from the remnant ovarian pedicle was carried out. Same procedures were repeated on the other ovary. After the removal of the ovaries, the peritoneum and the abdominal transverse muscle were sutured together, and a second layer of sutures was used to close the internal and external abdominal oblique muscles. Both layers were sutured with synthetic absorbable suture USP2 (Surgicryl® Polyglycolic Acid PGA, SMI, Belgium). The subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed with simple interrupted sutures using the same suture thread.

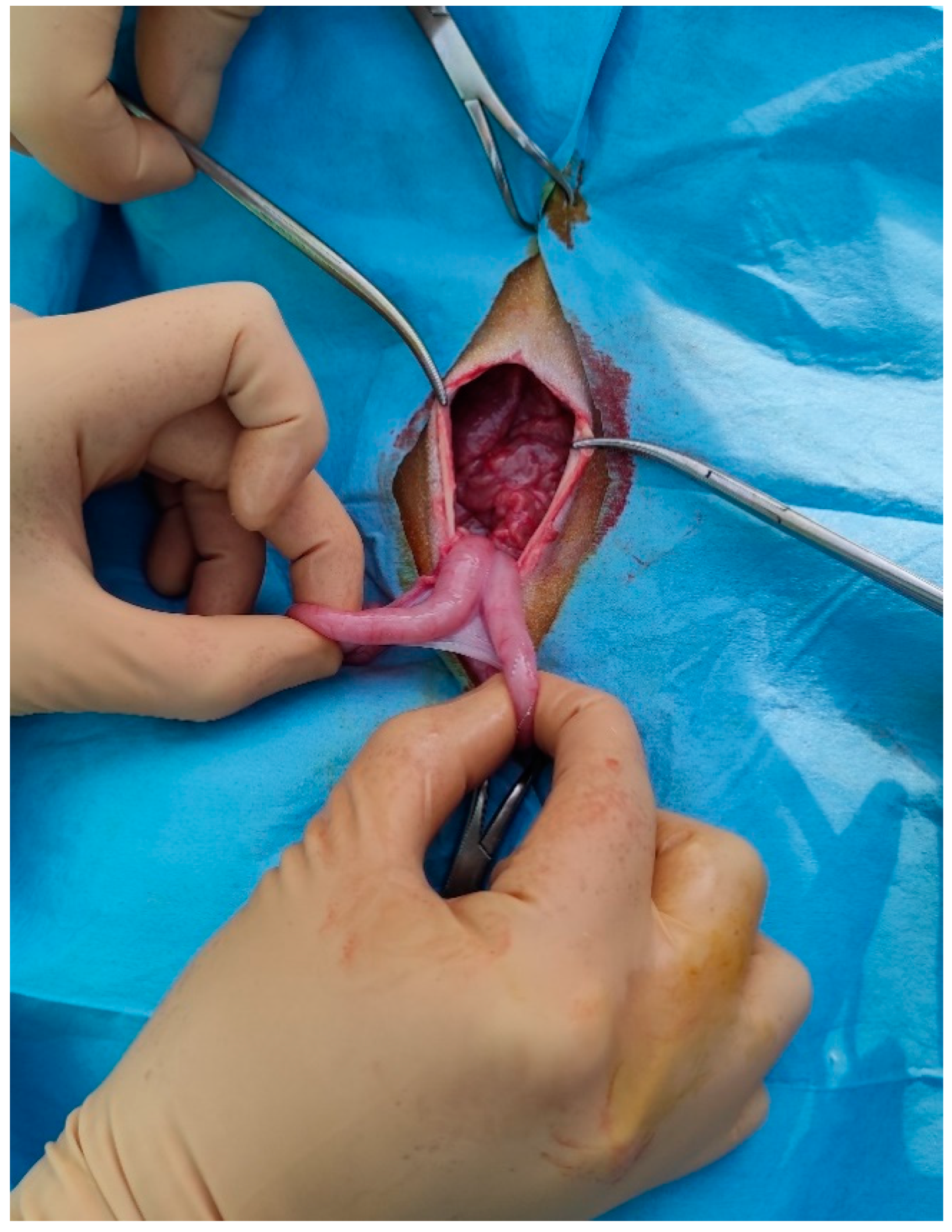

Ten animals were ovariectomized via linea alba approach (

Figure 4).

The incision was performed forward at the udder, at about 10 cm from the umbilical scar. The skin was incised and the linea alba was identified. It was raised, by means of a surgical clamp, and an incision was performed with a scalpel. The incision was enlarged with scissors. The surgeon grasped the uterus, using fingers, and exteriorized, locating the ovaries (

Figure 5).

Thereafter, the procedures were like those described above. After the removal of the ovaries, abdominal wall was sutured with a continuous suture using a synthetic absorbable suture thread USP2 (Surgicryl® Polyglycolic Acid PGA, SMI, Belgium). The subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed with simple interrupted sutures using the same suture thread.

At the end of the surgery subcutaneous (SC) injection of triidrate amoxicilline (Betamox LA 150 mg/mL, Vètoquinol Italia S.r.l., Bertinoro FC, Italy) 15 mg/kg and the IM injection of 0.3 mg/kg ketoprofen (Zooketo 100 mg/mL, Elanco Italia S.p.A., Milano, Italy) were administered as the antibiotic and anti-inflammatory coverage for the post-operative period.

After the operations were completed, the animals were placed in special cases to ensure a peaceful and safe awakening. During this period, the animals were monitored by the veterinary staff. Once fully awake, the animals were housed in a small stable within the enclosure.

2.5. Intra-Operative Evaluations

According to De Carvalho et al. (2016) for intra-operative nociception evaluation, the parameters of HR, RR, MAP and T, taken from the multiparameter monitor, were considered at five different times:

- -

Surgical preparation (with the animal under general anesthesia) (T0);

- -

Skin incision (T1);

- -

Resection of the left ovary (T2);

- -

Resection of the right ovary (T3).

- -

End of surgery (application of the last stitch to the skin) (T4).

2.6. Post-Operative Evaluations

All the animals were observed during post-surgery at 1, 3, 5 12 e 24 hours by the veterinary staff evaluating behavioral changes, such as reluctance to move, reduced feed intake, altered social interaction, and changes in posture. In case of the appearance of pain symptoms, IM injection of 0.3 mg/kg ketoprofen (Zooketo 100 mg/mL, Elanco Italia S.p.A., Milan, Italy) would be administered. After that, the day after surgery, animals were released in a large enclosure.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data collected were entered into a database using an excel spreadsheet and data analysis was performed with the statistical software SPSS 19 (IBM, NY). The continuous variables were described with mean ± standard deviation (SD). the Shapiro-Wilk test and Bartlett's test were used to assess the distributional normality and homoschedasticity of the continuous variables; a normalization model was set up for those not normally distributed. The GLM (General Linear Model) test for repeated measures with LSD (Least Significant Difference) post-hoc test was used for within-group comparisons, while Student's t-test was used for between-group comparisons. For all tests, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All surgeries were completed, and no intra- or post-operative complications occurred. The data about the duration of surgery, anesthesia and recovery were showed in Table1. No statistically difference was observed between the groups for these parameters.

During the surgeries, no increase in parameters of more than 25% compared to initial values occurred and then no animals were treated with a bolus of fentanyl as rescue analgesia. The HR, RR, T, SpO

2 and MAP values, measured during intra-operative procedure, are showed in the

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The HR trend is similar between the groups from T0 to T1. In group A there is a rapid increase in HR values from T2 to T3. Statistically difference between the groups were observed at T2 and T3 (

Table 2).

Regarding the RR trend, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups. In group F, there was a statistically significant reduction between T3 and T4, while in group A there were statistically significant differences between the times and there was a slight increase in the values at T1 (

Table 3).

The T had a progressive reduction in both groups: statistically significant differences were observed within the groups, as shown in

Table 4.

SpO

2 and MAP values were very similar in both groups. No statistically significant differences were observed either between groups or between times (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

As pain evaluation after surgery, no animals needed further analgesic administration and all were released the next day after surgery without any complications.

4. Discussion

Ovariectomy, performing in the field, has been widely used to control the density of wild ungulate populations and has been found to be the most effective for its cost and long-term effects (Denicola & Denicola, 2021). Considering the above, the purpose of this study was to compare the laparotomic approach at the flank with the approach via linea alba as surgical techniques to perform ovariectomy, in field conditions, in mouflons, to control their births.

The duration of surgery, duration of anesthesia, and recovery time of the animals were considered for comparison; in addition, intra-operative nociception, by means of the parameters of HR, RR, T, SpO2, and MAP, post-operative pain, by observation of algic manifestations of the animals, and intra- and post-operative complications. Abubakar et al. 2014 evaluated the differences between the surgical approach from flank and from linea alba, in goat. Lateral access appears to be the most widely used technique for approaching the abdomen of small ruminants; it allows surgery to be performed under local anesthesia, although it cannot used in this study, as they are wild animals. The advantages of lateral access in wild animals are the ability to remotely observe the surgical site and the lower potential risk of evisceration in case of wound dehiscence due to the overlapping arrangement of the oblique muscles of the abdomen (Abubakar et al., 2014; Yun et al., 2021). The ventral approach is an alternative with few intra- and post-operative complications, as the linea alba is incised, which has a lower incidence of bleeding (Abubakar et al., 2014). The disadvantage of ventral laparotomy is related to the risk of evisceration in the event of surgical wound dehiscence (MacLean et al., 2006).

Moreover, the use of vascular dissection and coagulation device allows a reduction in surgical time and safety in tissues bleeding control as reported by Lacitignola et al. 2022 and Cicirelli et al. 2023. In this study, in both groups, Caiman® (Aesculap - Tuttlingen) was used to perform the surgeries and there were no intra- or post-operative complications.

No statistically significant differences between the two groups were also found for surgical duration (about 20 minutes), anesthesia duration (about 50 minutes) and recovery time (about 18 minutes); so both techniques are considered effective and easy to perform.

Regarding the intra-operative evaluated parameters, statistically significant differences between the two groups were found at T2 and T3, for HR values. Specifically, there was a rapid increase in HR, evident only in group A, at T2, which was kept consistently high until T3. In the approach from the linea alba, in fact, there is increased tension exerted on the ovarian pedicle, to exteriorize the ovaries, which represents a nociceptive stimulus, detectable by the increase in HR. However, it should be considered that these values do not exceed 25% of the baseline value of the same group at T0, so it is within normal ranges such that rescue analgesia during surgery was not necessary. With reference to the intra-operative values of RR, T, SpO2 and MAP, no statistically significant differences were found between groups F and A.

There is a lack of references in the literature on the assessment of post-operative pain in mouflons; in fact, it remains hard to be able to assess antalgic attitudes in wild animals, for this pain was evaluated only with the observation of behavioral changes. In both groups, no alteration was observed.

5. Conclusions

It can be argued that the two surgical approaches, taking into consideration the duration of surgery, the parameters intra-operative evaluated and the intra- and post-operative complications, have not shown relevant differences that make one lean toward the choice of one over the other. What can be affirmed is that the use of access surgery from the flank allows better monitoring of the healing of the surgical wound at a distance and avoids eventual evisceration by wound dehiscence. Such aspects represent a major advantage in the management of wildlife.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C., Methodology, M.B., A.R.; Validation, A.C.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B., A.R., V.C. L.F.; resources, A.R. data curation; A.C.; visualization, F.L.; supervision, A.R., V.C., F.G.; project administration, A.R. funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by: 1. The agreement with the National Park Authority of the Tuscan Archipelago, protocol number 3785-III/14, in the ambit of activities conducted within the project LIFE18NAT/IT/000828 LETSGO GIGLIO “Less alien species in the Tuscan Archipelago: new actions to protect Giglio island habitats”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the ethicalguidelines of the Animal Welfare Committee. Institutional Review Board approval of the study was obtained from the University of Bari Aldo Moro with approval number 20/2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Agreement with the National Park Authority of the Tuscan Archipelago, protocol number 3785-III/14.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Francesca Giannini, responsible scientist of the Natural Park of the Tuscan Archipelago.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abubakar, A. A., Andeshi, R. A., Yakubu, A. S., Lawal, F. M., & Adamu, U. (2014). Comparative Evaluation of Midventral and Flank Laparotomy Approaches in Goat. Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bechert, U., Bartell, J., Kutzler, M., Menino, A., Bildfell, R., Anderson, M., & Fraker, M. (2013). Effects of two porcine zona pellucida immunocontraceptive vaccines on ovarian activity in horses. Journal of Wildlife Management, 77(7), 1386–1400. [CrossRef]

- Beringer, J., Hansen, L. P., Demand, J. A., Sartwell, J., Wallendorf, M., & Mange, R. (1973). Efficacy of Translocation to Control Urban Deer in Missouri: Costs, Efficiency, and Outcome. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 30(3), 767–774. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3784230%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/3784230?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/page/.

- Boulanger, J. R., & Curtis, P. D. (2016). Efficacy of surgical sterilization for managing overabundant suburban white-tailed deer. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 40(4), 727–735. [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, J. R., Curtis, P. D., Cooch, E. G., & Denicola, A. J. (2012). Sterilization as an alternative deer control technique: A review. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 6(2), 273–282.

- Caulkett, N., & Haigh, J. C. (2007). Wild Sheep and Goats. In G. West, D. Heard, & N. Caulkett (Eds.), Zoo Animal & Wild Life-Immobilization and Anesthesia (1th Editio, pp. 629–633). Blackwell Publishing Professional, 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa, USA.

- Cicirelli, V., Carbonari, A., Burgio, M., Giannini, F., & Rizzo, A. (2023). Ovariectomy in Mouflons (Ovis aries) in the Field: Application of Innovative Surgical and Anaesthesiological Techniques. Animals, 13(3), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cicirelli V, Burgio M, Lacalandra GM, Aiudi GG. Local and Regional Anaesthetic Techniques in Canine Ovariectomy: A Review of the Literature and Technique Description. Animals (Basel). 2022 Jul 27;12(15):1920. PMID: 35953908; PMCID: PMC9367435. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, L. L., Nishimura, L. T., Borges, L. P., Cerejo, S. A., Villela, I. O. J., Auckburally, A., & Mattos, E. (2016). Sedative and cardiopulmonary effects of xylazine alone or in combination with methadone, morphine or tramadol in sheep. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 43(2), 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Denicola, A. J., & Denicola, V. L. (2021). Ovariectomy As a Management Technique for Suburban Deer Populations. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 45(3), 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Gionfriddo, J. P., Denicola, A. J., Miller, L. A., & Fagerstone, K. A. (2011). Efficacy of GnRH immunocontraception of wild white-tailed deer in New Jersey. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 35(3), 142–148. [CrossRef]

- Gionfriddo, J. P., Eisemann, J. D., Sullivan, K. J., Healey, R. S., Miller, L. A., Fagerstone, K. A., Engeman, R. M., & Yoder, C. A. (2009). Field test of a single-injection gonadotrophin-releasing hormone immunocontraceptive vaccine in female white-tailed deer. Wildlife Research, 36(3), 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J. O., Hyndman, T. H., Barnes, A., & Collins, T. (2015). Is wildlife fertility control always humane? Animals, 5(4), 1047–1071. [CrossRef]

- Krause, S. K., Kelt, D. A., Gionfriddo, J. P., & Van Vuren, D. H. (2014). Efficacy and health effects of a wildlife immunocontraceptive vaccine on fox squirrels. Journal of Wildlife Management, 78(1), 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Kutzler, M., & Wood, A. (2006). Non-surgical methods of contraception and sterilization. Theriogenology, 66(3 SPEC. ISS.), 514–525. [CrossRef]

- Lacitignola, L., Laricchiuta, P., Guadalupi, M., Stabile, M., Scardia, A., Cinone, M., & Staffieri, F. (2022). Comparison of Two Radiofrequency Vessel-Sealing Device for Laparoscopic Ovariectomy in African Lionesses (Panthera Leo). Animals, 12(18). [CrossRef]

- Laundré, J. W., Hernández, L., & Altendorf, K. B. (2001). Wolves, elk, and bison: reestablishing the “landscape of fear” in Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 79(8), 1401–1409. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, R. A., Mathews, N. E., Grove, D. M., Frank, E. S., & Paul-Murphy, J. (2006). Surgical technique for tubal ligation in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 37(3), 354–360. [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, K. D., Van Deelen, T. R., Drake, D., Kesler, D. J., & VerCauteren, K. C. (2010). Contraceptive efficacy of a novel intrauterine device (IUD) in white-tailed deer. Animal Reproduction Science, 117(3–4), 261–265. [CrossRef]

- Massei, G. (2023). Fertility Control for Wildlife: A European Perspective. Animals, 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Massei, G. Massei, G., Cowan, D., & Eckery, D. (2014). Novel management methods: Immunocontraception and other fertility control tools. USDA National Wildlife Research Center Symposia, 209–235. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc%5Cnhttp://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/1675.

- Massei, G., Quy, R. J., Gurney, J., & Cowan, D. P. (2010). Can translocations be used to mitigate humanwildlife conflicts? Wildlife Research, 37(5), 428–439. [CrossRef]

- Merrill, J. A., Cooch, E. G., & Curtis, P. D. (2006). Managing an Overabundant Deer Population by Sterilization: Effects of Immigration, Stochasticity and the Capture Process. Journal of Wildlife Management, 70(1), 268–277. [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. A., Gionfriddo, J. P., Fagerstone, K. A., Rhyan, J. C., & Killian, G. J. (2008). The single-shot GnRH immunocontraceptive vaccine (GonaConTM) in white-tailed deer: Comparison of several GnRH preparations. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 60(3), 214–223. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M. E., Montag, J. M., & Williams, D. R. (2003). The urbanization of wildlife management: Social science, conflict, and decision making. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 1(3), 171–183. [CrossRef]

- Powers, J. G., Monello, R. J., Wild, M. A., Spraker, T. R., Gionfriddo, J. P., Nett, T. M., & Baker, D. L. (2014). Effects of GonaCon immunocontraceptive vaccine in free-ranging female Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). Wildlife Society Bulletin, 38(3), 650–656. [CrossRef]

- Quy, R. J., Massei, G., Lambert, M. S., Coats, J., Miller, L. A., & Cowan, D. P. (2014). Effects of a GnRH vaccine on the movement and activity of free-living wild boar (Sus scrofa). Wildlife Research, 41(3), 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Rutberg, A. T., Naugle, R. E., & Verret, F. (2013). Single-treatment porcine zona pellucida immunocontraception associated with reduction of a population of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus Virginianus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 44(4 SUPPL). [CrossRef]

- Warren, R. J. (2000). Overview of Fertility Control in Urban Deer Management. Proceedings of the 2000 Annual Conference of the Society for Theriogenology, August, 237–246.

- Warren, R. J. (2011). Deer overabundance in the USA: Recent advances in population control. Animal Production Science, 51(4), 259–266. [CrossRef]

- Yun, T., Kim, J., & Kang, H. G. (2021). Lateral flank approach for ovariohysterectomy in a lion (Panthera leo) with a ruptured pyometra. Veterinary Sciences, 8(11), 4–9. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Surgical site to perform ovariectomy by flank approach in a muflon.

Figure 1.

Surgical site to perform ovariectomy by flank approach in a muflon.

Figure 2.

Uterus and ovary of a mouflon exteriorized from the flank surgical site.

Figure 2.

Uterus and ovary of a mouflon exteriorized from the flank surgical site.

Figure 3.

CAIMAN® forceps placed at the base of the ovarian pedicle.

Figure 3.

CAIMAN® forceps placed at the base of the ovarian pedicle.

Figure 4.

Surgical site to perform ovariectomy from the linea alba in a mouflon.

Figure 4.

Surgical site to perform ovariectomy from the linea alba in a mouflon.

Figure 5.

Uterus and ovary of a mouflon exteriorized from the linea alba surgical site.

Figure 5.

Uterus and ovary of a mouflon exteriorized from the linea alba surgical site.

Table 1.

Surgery duration, anesthesia duration and recovery time of F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) muflons expressed as mean ± standard deviation (± SD).

Table 1.

Surgery duration, anesthesia duration and recovery time of F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) muflons expressed as mean ± standard deviation (± SD).

| Groups |

Surgical duration

(minutes)

|

Anesthesia duration

(minutes)

|

Recovery time

(minutes)

|

| Flank (F) |

18 ± 7.08 |

47.2 ± 15.26 |

14.6 ± 3.03 |

| Alba (A) |

17.8 ± 1.55 |

46.2 ± 8.28 |

15.6 ± 3.12 |

Table 2.

Heart rate (HR) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In column: A,B: P<0.01; C,D: p<0.05 In the row: a,b: c,d p<0.05.

Table 2.

Heart rate (HR) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In column: A,B: P<0.01; C,D: p<0.05 In the row: a,b: c,d p<0.05.

| Group |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| Flank (F) |

94.1 ± 10.55 |

90.7 ± 7.69a |

80.6 ± 15.36Ab |

90.7 ± 15.34C |

87.8 ± 19.3a |

| Alba (A) |

93.7 ± 12.87a |

88 ± 15.62ac |

104.7 ± 4.03Bb |

104.6 ± 8.72Dd |

88.8 ± 16.68ac |

Table 3.

Respiratory rate (RR) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In the row: a, b: p<0.05.

Table 3.

Respiratory rate (RR) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In the row: a, b: p<0.05.

| Group |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| Flank (F) |

30.9 ± 5.43 |

30.2 ± 5.47 |

31.8 ± 6.41 |

30.7 ± 4.37a |

26.9 ± 3.93b |

| Alba (A) |

29 ± 3.56a |

33.6 ± 8.26b |

30.3 ± 8.18a |

29.2 ± 6.41a |

26 ± 1.63a |

Table 4.

temperature (T) values (°C) of muflons of group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation (± SD), at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In the row: a,b; c,d; e,f; f,g: p<0.05.

Table 4.

temperature (T) values (°C) of muflons of group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation (± SD), at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch on the skin). In the row: a,b; c,d; e,f; f,g: p<0.05.

| Group |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| Flank (F) |

39.05 ± 0.91a |

39.16 ± 0.83c |

38.54 ± 0.49de |

38.42 ± 0.47bdg |

38.10 ± 0.37bdf |

| Alba (A) |

38.79 ± 0.46a |

38.75 ± 0.79a |

38.19 ± 1.06b |

38.31 ± 0.83b |

37.81 ± 0.26b |

Table 5.

Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch to the skin).

Table 5.

Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) values of muflons in group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch to the skin).

| Group |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| Flank (F) |

98.3 ± 2.26 |

98.7 ± 1.83 |

98 ± 1.41 |

98.3 ± 1.49 |

97.7 ± 2.71 |

| Alba (A) |

97.7 ± 2.63 |

97.7 ± 3.13 |

98.7 ± 1.25 |

98.4 ± 1.51 |

97.8 ± 2.25 |

Table 6.

mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) values (mmHg) of muflons group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch).

Table 6.

mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) values (mmHg) of muflons group F (ovariectomized via flank approach) and A (ovariectomized via linea alba approach) expressed as mean ± standard deviation, at time T0: baseline; T1: skin incision; T2: left ovary manipulation and removal; T3: right ovary manipulation and removal; T4: end of surgery (after application of the last stitch).

| Group |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

| Flank (F) |

64.4 ± 19.36 |

61.7 ± 14.25 |

67 ± 22.11 |

68.4 ± 19.48 |

69.10 ± 10.97 |

| Alba (A) |

62.9 ± 4.25 |

61.4 ± 11.96 |

72.2 ± 17.42 |

72.7 ± 16.29 |

71.6 ± 27.23 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).