1. Introduction

Currently, insurance inclusion has caught the attention of development partners and scholars as the missing link to full financial inclusion. Such attention emanates from the soaring levels of insurance inclusion. Globally, insurance penetration is estimated at 7%, while in Africa, insurance penetration is estimated at 2.78 % (International Association of Insurance supervisors, 2022). In Uganda, insurance penetration is estimated at 0.80%. However, 99% of the adult population is not insured, yet, the people and businesses are susceptible to lifecycle shocks (Finscope, 2018). According to Cheston et al. (2018) “insurance inclusion is the state of access to and use of appropriate and affordable insurance products for the unserved and underserved”. Arguably, studies have proved insurance to contribute to economic growth at the macro level and poverty alleviation at the micro level (Bayar, 2021; Zulfiqar et al., 2020). Hence, inclusive insurance can enable poverty alleviation through savings mobilization for entrepreneurship and reducing people’s risk susceptibility (Kim et al., 2018).

Notably, insurance exclusion has been attributed to behavioral and non-behavioral factors. Behavioral factors such as trust, perceived value and insurance literacy have been found to influence insurance inclusion (Kiwanuka and Sibindi, 2023; Cruijsen et al., 2019). Additionally, non-behavioral factors such as transaction costs, documentation requirements and distance influence insurance inclusion (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., (2018). Notwithstanding, insurance inclusion continues to remain very low, especially in emerging economies. As such, developing economies are currently leapfrogging insurtech to broaden insurance inclusion (Holliday, 2019). However, insurtech is thought to have improved insurance penetration more in the developed economies compared to the developing economies (Reddy et al., 2020). Hence contributing to the persistence of the insurance inclusion gap between the developed and developed countries.

Despite rolling out insurtech in the insurance landscape, African countries are lagging behind in embracing the technology and still grappling with low insurance inclusion (Sibindi, 2022). Yet, financial technologies are playing a significant role in creating access to the unserved and underserved people, especially in the rural areas. According to Gautum and Kanoujiya (2022), governments need to adopt and promote the usage of financial technologies of mobile money and the like to promote the uptake of financial services. Digital networks render technological platforms through which financial services providers expand their reach to the unserved and underserved segments (Kanga et al., 2022). However, in today’s Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), scores of researches have earmarked the importance of digital financial literacy to foster financial services uptake (Setiawan et al., 2022; Rahayu et al., 2022). Conclusively, these studies have found digital financial literacy to influence financial inclusion. According to Gautum and Kanoujiya (2022), given today’s proliferation of digital financial services, consumer’s financial literacy level alone is not enough to foster financial inclusion. Therefore, significant attention needs to be paid to the people’s digital financial literacy.

Albeit previous studies emphasising the importance insurance literacy to foster insurance inclusion (Kiwanuka and Sibindi, 2023; Cruijsen et al., 2019), few studies have investigated the influence of digital literacy on insurance inclusion. Moreover, despite the emphasized importance of insurtech towards access to insurance services, barely any study has explained how digital literacy and insurtech interplay to influence insurance inclusion. However, previous studies proffer mixed results on the association between digital literacy and adoption of technology. Some studies found digital literacy to influence technology adoption (see for instance Kabakus et al., 2023; Nikou et al., 2022) while others find digital literacy not to influence technology adoption (see for instance Kabakus et al., 2023; Jang et al., 2021). Moreover, the foregoing studies were conducted in work settings and learning institutions. Thus, the need to particularly investigate how digital literacy and insurtech influence insurance inclusion.

Against this backdrop, we sought to examine how digital literacy and insurtech influence insurance inclusion in the Ugandan context. Distinctly, we aimed to examine the mediating role of insurtech adoption in the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion. As such, our study cross-sectionally surveyed individuals that have used digital platforms such as mobile phones and computers to access insurance in Uganda. The study hypotheses were tested through PLS-SEM We found digital literacy and insurance inclusion to be significantly and positively related. Also, insurtech adoption was found to positively influence variations in insurance inclusion. More so, digital literacy was found to positively influence insurtech adoption. Further, a significant partial mediation effect of insurtech adoption in the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion in Uganda was found.

The article sections are oraganised as follows:

Section 2 discusses the related literature. The third section details study’s methodology;

Section 4 entails the findings;

Section 5 discusses the findings;

Section 6 summarises the study.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical review

The Technology Acceptance model (TAM) by Davis (1989) was used to examine the mediating role of insurtech adoption between digital literacy and insurance inclusion. We sought to determine how TAM constructs mediate the association between digital literacy and insurance inclusion in Uganda. The TAM (Davis 1989) is a theory that explains users’ acceptance and usage of technologies. In that regard, the TAM theory (Davis, 1989) postulates that actual technology usage is directly or indirectly influenced by; perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and attitude towards usage of the technology. In the TAM, perceived usefulness implies the extent to which the technology improves user’s activity performance while perceived ease of use denotes how the user perceives the technology as effortless. In addition, attitude towards usage denotes the cause of intention leading to future behaviour. When a technology is not easy to use, it might not be perceived as useful (Gie and Fenn, 2019). Ajzen and Fishbein (2000) buttress that the usage attitude has an evaluative effect of positive and negative feelings of people in performance of a specific behaviour. In the TAM perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and attitude towards use predict actual usage and behavioral intentions of users (Nikou et al., 2022). According to Elkaseh et al. (2016), perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use influence behavioral intention. Accordingly, the TAM (Davis, 1989) is adopted in the current study to understand how adoption of insurtech influences insurance buying behaviour of individuals by mediating the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Digital literacy and Insurance Inclusion

In the wake of the current digital revolution, being digitally literate is considered a vital quality that people must have (Hassan et al., 2022). Presently, almost all financial products and services are provided digitally (Prasad et al., 2018). As such, in addition to the traditional financial literacy, digital literacy is increasingly fostered to broaden financial inclusion (Lyons and Hass-Hanna, 2021). People can only actively partake in the current digital economy if they are knowledgeable and skilled to undertake digital financial transactions (Kass-Hanna et al., 2022). Despite the digitisation to foster increased access to financial services, most of the people are not aware of how to operate the digital technologies (Hassan et al., 2022). According to the Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2022), almost two thirds of the unbanked do not know how to use mobile money accounts. Regardless, Wang et al. (2022) found digital literacy among the elderly and middle-aged people to significantly influence the possibility of participating in financial markets. People without digital literacy are less represented in financial investment. Markedly, in the current digital financial services-based economy, being financially literate alone is inadequate (Chan et al., 2022), hence the need to focus on the people’s digital financial literacy. As such, digital financial literacy skills and financial literacy enable efficient usage of financial services and protection against risks (Rahayu et al., 2022). Thus, we hypothesise that;

H1. Digital literacy positively influences insurance inclusion in Uganda.

2.2.2. Insurtech and insurance inclusion

Insurtech, a subset of fintech, is the application of technology to deliver insurance specific solutions through innovations for traditional and nontraditional market players (Bittin et al., 2022). Although insurtech emerged much later than fintech for the banking sector, it has entrenched every part of the insurance industry (Lin and Chen, 2020). Principally, with the introduction of financial technologies, access to financial services has improved significantly (Asif et al., 2023). As such, Gautum and Kanoujiya (2022) buttressed that governments need to adopt financial technologies to proliferate financial inclusion programmes across all levels. With the fourth digital revolution, financial technologies are expected to deepen the global financial inclusion index (Rosyadah et al., 2021). According to Beck (2020), Mobile phone technologies have enabled developing countries to leapfrog traditional financial services provision models to increase broader access to financial services and products. Digitalisation enables transactions across larger geographical coverages and at faster speeds (Rosyadah et al. 2021). According to Sibindi (2022), it was established that ICT significantly impacts on insurance market development in Africa. Particularly, the penetration of mobile phones usage has a significant positive impact on consumption of life insurance (Asongu and Odhiambo, 2020). Accordingly, this study hypothesises that;

H2.

Insurtech adoption influences insurance inclusion in Uganda.

2.2.3. Digital literacy and insurtech adoption

Although financial technologies have been argued to promote financial inclusion (Rosyadah et al., 2021; Beck, 2020), Morgan et al. (2019) argue that to achieve increased financial inclusion, it will require higher levels of digital literacy to effectively use the financial technologies. Furthermore, Nikou et al. (2022) argued that the obstacle to digitalisation lies in making people to know how to use the technology. Thus, the fast introduction of digital technologies has rendered digital skills important (Mikheev et al., 2023). However, previous literature on the influence of digital literacy and technology adoption has found mixed results. According to Kabakus et al. (2023), digital literacy was found to directly influence perceived ease of use but not perceived usefulness. On the one hand, in their research on higher education institutions in Finland, Nikou and Aavakare (2021) found digital literacy to have no influence on the student’s intention to use digital technologies. On the other hand, while investigating the effect of digital literacy on intention to use e-learning among small and medium enterprises in Mohammadyari and Singh (2015) found digital literacy to significantly influence intention whether to or not continue using web 2.0 technologies. On this footing, it can be deduced that the influence of digital literacy on technology adoption is inconclusive. Regardless, prior studies attribute digital exposure to adoption of technologies (Kabakus et al., 2023; Moenjak et al., 2020). Therefore, based on the foregoing, the current study hypothesizes that;

H3. Digital literacy positively influences insurtech adoption

H4. Insurtech adoption mediates the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Authors own conceptualisation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Authors own conceptualisation.

3. Research Methodology

In this study, we cross-sectionally gathered the quantitative data to estimate the study hypotheses. This design was adopted owing to its ability to provide large amounts of data at a point in time. The data were collected from individuals that have used digital platforms such as mobile phones and computers to access insurance products and services in Uganda. The study participants were clients of three insurance providers (Yeko, Turaco and Prudential) that have adopted insurtech to extend insurance services in Uganda (Insurance Regulatory Authority, 2022). The data was collected by distributing questionnaires to the study participants. Overall, a sample of 391 participants partook in the current study. Yamane’s (1973) sample size determination formula [n = N/1 + N (e)2] was adopted to arrive at the sample. The study participants were selected through a single stage sampling procedure. Accordingly, the study participants were selected using proportionate stratified simple random sampling. This sampling procedure enabled to give equal chance to all the participants to partake in the study. A structured questionnaire with response items ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree was adopted to gather the primary data. Prior to data collection, participants’ consent to partake in the study was sought. Notably, the complete data was tested for robustness. The data were tested for validity and reliability. Accordingly, discriminant and convergent reliability were performed. Additionally, multicollinearity among variables was tested for using the Variance Inflation Factors. The Diagnostic findings are presented in the next section. The measurements of the study variables were adopted from previous studies. Digital literacy was measured using knowledge (KNW) and skill (SKL) as adopted from Hassan et al. (2022); Kass-Hanna et al. (2022). Insurtech adoption was measured by perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceive usefulness (PU) as suggested by Davis (1989). While the measures for insurance inclusion were access (ACS) and usage (USG)as suggested by Kiwanuka and Sibindi (2023); Cheston et al. (2018).

4. Empirical Results Presentation and Analysis

4.1. Diagnostic results

Diagnostics were run to establish any biases that could compromise reliability of the research findings. Data were checked for composite reliability, discriminant validity, content validity, construct validity and tests for multicollinearity.

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the results from the diagnostic tests. Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient was used to test for composite reliability, where values above 0.70 were accepted (Hair

et al., 2019). Alike, discriminant validity and multicollinearity were tested using the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) and Average variance extracted as guided. Discriminant validity and multicollinearity results are presented in

Table 2. The diagnostics revealed all the study variables to be above 0.70 cut off and below the 0.95 upper limit. Additionally, all the results for the Average variance extracted (AVE) were above the 0.5 cut-off. Similarly, it was established that there was no multicollinearity since all the variance inflation factors (VIFs) were below 5 as guided by Hair et al (2019).

4.2. Sample Characteristics

The results in

Table 3 showed that there were more females accessing insurance via digital platforms compared to the male counterparts. The female respondents comprised 57.1% of the sample while the males were 42.9% of the sample. The findings also indicated most of the respondents to be in the age range of 34-49 years with a 49.7% sample representation. Additionally, 45.7% of the respondents were in the age range of 18-33 years. Only 4.6 % of the study sample was in the age range of 50-65 years. In terms of level of education, majority of the respondents indicated to be degree holders at 65.7% of the sample, followed by diploma holders at 14,6% of the sample. Further, 10.7% of the respondents held masters’ degrees while only 5.1% and 2.6 % of the respondents had advanced level UACE and UCE respectively. Also, Results showed that only 1.3% of the respondents had PhDs while there were no respondents with Primary Leaving Certificate. Lastly, 91.6% of the respondents indicated to have used the mobile phone platform to access insurance services, while 8.4% of the respondents used the computer to digitally access insurance products and services.

4.3. Correlational analysis

We used Pearson’s correlation to establish the relationship between digital literacy, insurtech adoption and insurance inclusion. The correlation results are indicated in

Table 4. The results show digital literacy to be positively and significantly associated with insurance inclusion (r = 0.525, p < 0.01). The results suggest that positive variances in digital literacy leads to positive variances in insurance inclusion. Also, the results also revealed a significant positive relationship between insurtech adoption and insurance inclusion (r = 0.683, p < 0.01). This suggests that as insurtech adoption increases, insurance inclusion increases significantly. Lastly, correlational results showed that digital literacy is positively associated with insurtech adoption (r = 0.532, p < 0.01). This finding suggests that, positive changes in digital literacy are associated with positive changes in insurance inclusion. Given that insurtech adoption is positively associated with both digital literacy and insurance inclusion, it is an indication that insurtech adoption can mediate the digital literacy and insurance inclusion nexus. Based on Hair

et al. (2019), a mediation effect suffices when the mediating variable is associated with both the independent and the dependent variable.

4.4. Structural equation modelling Results

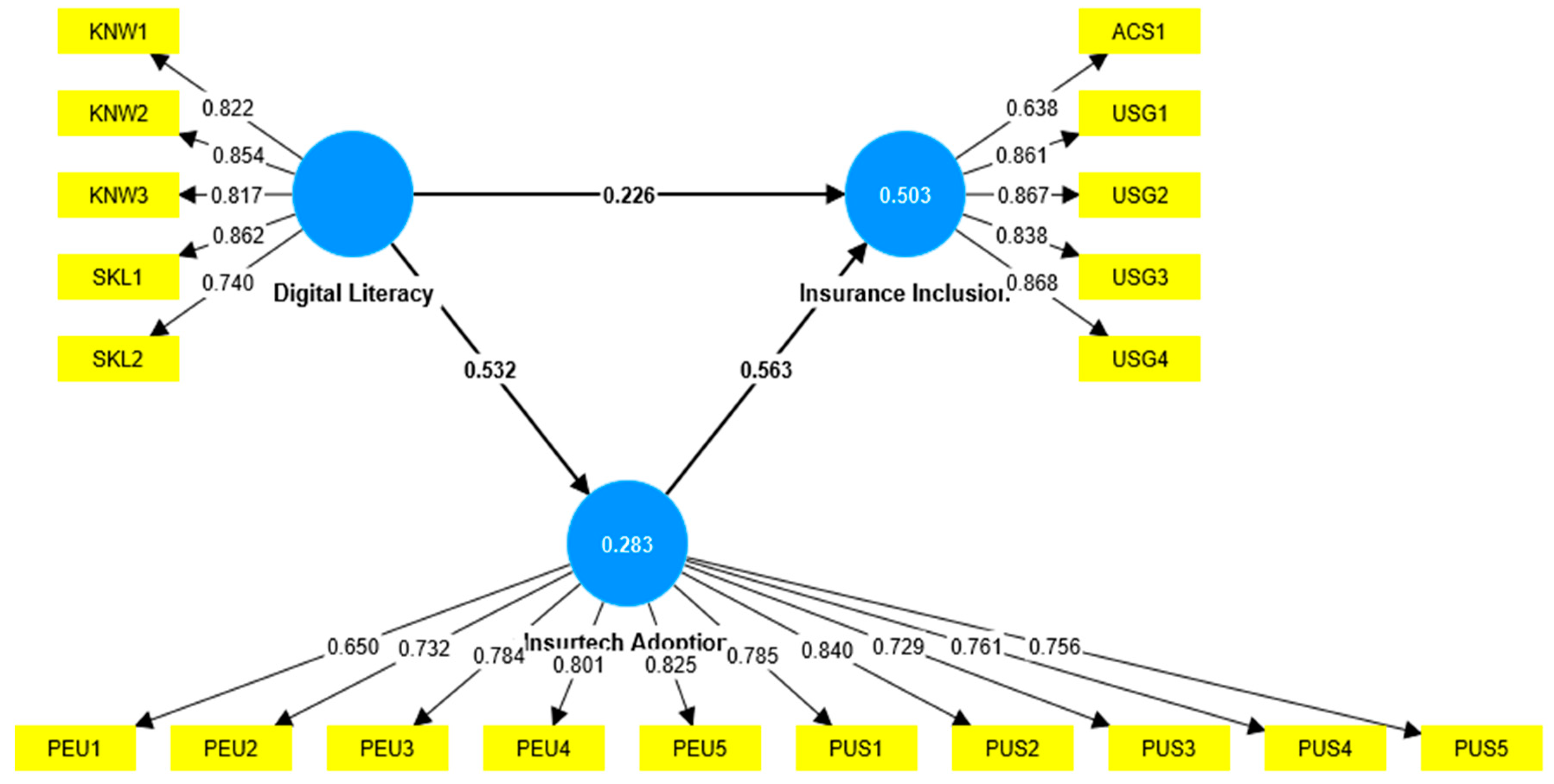

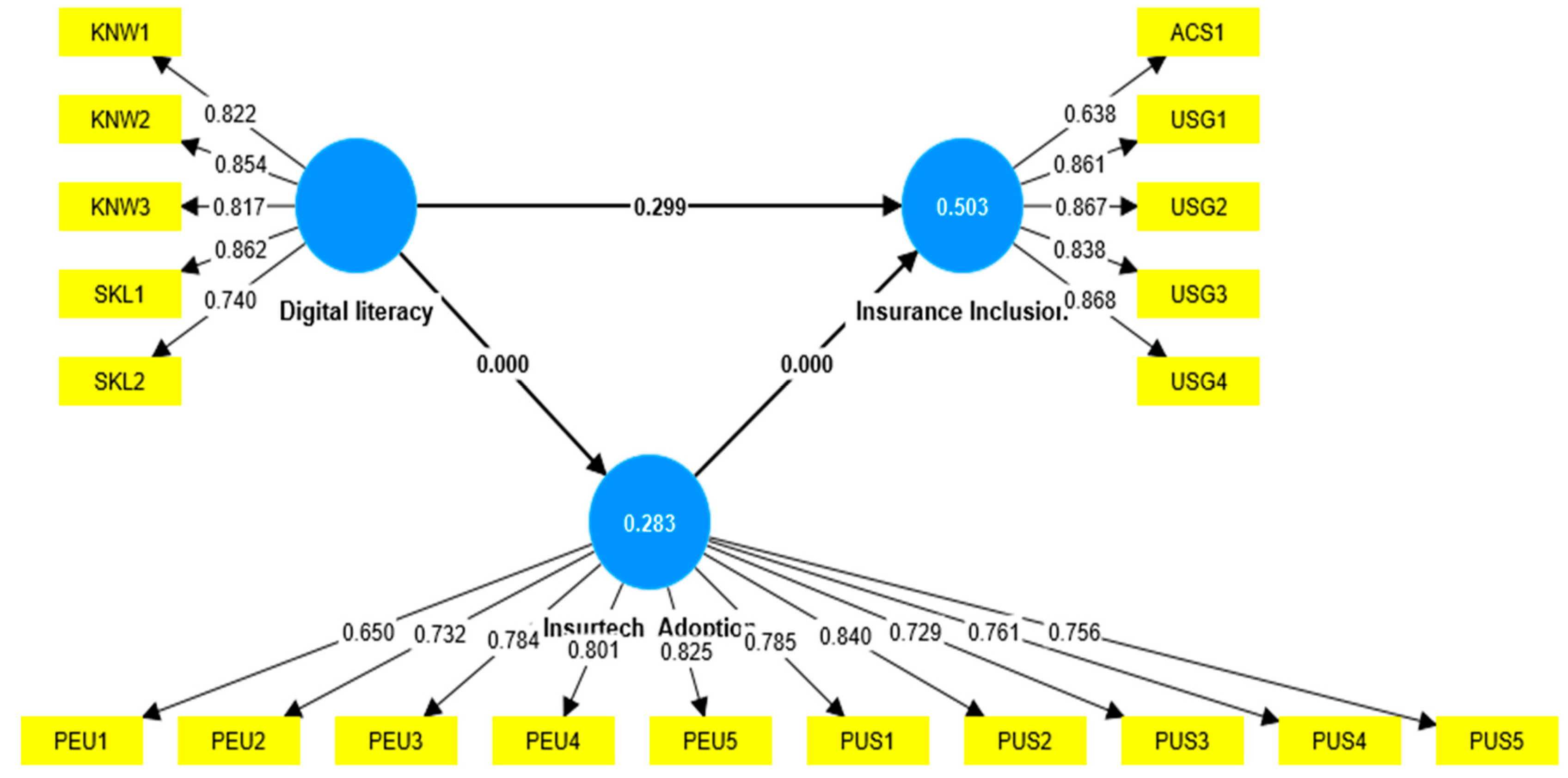

This study sought to establish the effect of digital literacy and insurtech adoption on insurance inclusion. Markedly, the study sought to establish the mediating role of insurtech adoption in the relationships between digital literacy and insurance inclusion in Uganda. As such, PLS-SEM was adopted to test the study hypotheses. PLS-SEM results revealed that digital literacy significantly and positively (β = 0.226; t = 3.940; p < 0.0001) influences insurance inclusion in Uganda. This finding supports hypotheses (H1). Furthermore, the findings revealed insurtech adoption has a significant positive impact (β = 0.563; t = 12.634; p < 0.0001) on insurance inclusion in Uganda. Hence hypothesis (H2) of is supported. Additionally, the study findings revealed that digital literacy significantly and positively influences insurtech adoption in Uganda (β = 0.532; t = 13.526; p < 0.0001). Hence hypothesis (H3) is supported. Particularly, the results revealed that insurtech adoption partially mediates the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion in Uganda (β = 0.299; t = 8.884; p < 0.0001). Hypothesis testing results are presented in

Table 5. Overall, the findings revealed that the direct and indirect effects of digital literacy and insurtech adoption explain 50.3% of variance in insurance inclusion as depicted in Figures 2 and 3. According to Hair et al. (2019), an R

2 of 0.26 and above is a substantial effect of the predictors on the exogenous variable. Thus, it can be inferred that the in current model, digital literacy and insurtech adoption sufficiently predict insurance inclusion in Uganda.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Algorithm with direct effects and factor loadings.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Algorithm with direct effects and factor loadings.

Figure 3.

PLS-SEM Algorithm with indirect effects.

Figure 3.

PLS-SEM Algorithm with indirect effects.

5. Discussion

This study sought to establish the influence of digital literacy and insurtech adoption on insurance inclusion in Uganda. As such, the study was anchored on four hypotheses that were all supported by the findings.

Firstly, the study findings revealed that digital literacy significantly and positively influences insurance inclusion in Uganda. This finding suggests that when consumers are knowledgeable about how to use digital devices such as computers, smart phones and other related devices, they can enroll on an insurance policy using such digital devices. Additionally, consumers’ digital literacy enables them to ably navigate and search for insurance information on the internet and other digital platforms. As well, when consumers are aware of the threats and risks associated with online transactions, they can have the confidence to buy insurance products and seek for insurance services through digital insurance platforms. The finding that digital literacy is associated with insurance inclusion is consistent with Kass-Hanna et al. (2022), who argue that people can only actively partake in the current digital economy when they are knowledgeable and skilled to undertake digital finance transactions. Moreover, extant studies have argued that in addition to the traditional financial literacy, there is need to foster digital financial literacy to broaden financial inclusion (Lyons and Hass-Hanna, 2021; Lyons et al., 2020). When people lack digital knowledge and skills, they will not be financially included (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2022). The study’s findings are also in agreement with Rahayu et al., (2022), they argued that digital and financial literacies enable efficient usage of financial services and protection against risks. Also, Kass-Hanna et al. (2022) found digital literacy to be helpful in building inclusive and financial resilience among the unserved and underserved population.

Secondly, the results reveal a significant association between insurtech adoption and insurance inclusion. This finding suggests that when consumers find ease in learning and using digital insurance platforms, they can subsequently enroll onto insurance digitally. Furthermore, it was revealed that when digital insurance platforms are user-friendly, clients are encouraged to use them to access insurance products and services. This finding resonates with extant studies which have advanced financial technologies to have the potency to influence or foster access to financial services (Asif et al., 2023; Sahay, 2022). However, such studies have been done mainly in the area of fintech and financial inclusion. In line with the current study, Holliday (2019) argued that insurtech has the potential to boost economic growth by closing the protection gap from a developing country perspective. This argument is in agreement with the current study’s finding that when clients can easily buy insurance policies through digital platforms such as mobile phones, they can enroll onto various digital insurance products and services, hence fostering insurance inclusion. The mobile phone network has enabled emerging countries to increase access to financial services and at faster speeds (Rosyadah et al., 2022; Beck, 2020). Our findings further indicate that, the efficiency in digital insurance platforms encourages individuals to continue using insurance in the future and also recommend others to enroll on insurance. Therefore, governments need to adopt financial technologies to proliferate financial inclusion programmes across all levels (Gautum and Kanoujiya, 2022).

Thirdly, this study’s findings revealed that digital literacy has a significant positive relationship with insurtech adoption. In this regard, the finding suggests that when individuals know how to use digital devices such as mart phones, computer and other related devices, they can easily utilise insurance technologies. Insurance technologies require individuals to have the ability to navigate and evaluate the digital platforms. Accordingly, one’s digital literacy will enable them to execute insurtech tasks such as enrolling on an insurance product, applying for insurance claims and logging insurance complaints through the insurtech platforms. This finding is consistent with extant literature on the one hand and inconsistent with extant literature on the other hand. On the one hand, this finding is in agreement with Kabakus et al. (2023), who found digital literacy to influence adoption of technologies. They found digital literacy to be associated with perceived ease of use. Nevertheless, although we found digital literacy to influence both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, Kabakus et al. (2023) did not find digital literacy to influence perceived usefulness. Additionally, this study’s findings are in agreement with Mohammadyari and Singh (2015) who found digital literacy to influence intention to or not to use web 2.0 technologies. On the other hand, the current study’s findings are inconsistent with Nikou et al. (2022) who fund digital literacy not to have a positive effect on technology usage in TAM context. Notwithstanding, the current study advances that, based on the TAM context, digital literacy influences insurtech adoption.

Fourthly, this study found that insurtech adoption mediates the digital literacy and insurance inclusion relationship. In that regard, this study makes an original contribution by positing that for a client’s digital knowledge and skills to influence insurance inclusion, significant portions of digital literacy go through insurtech adoption. Moreover, the findings revealed that digital literacy alone had a weak effect size on insurance inclusion compared to its effect size on insurtech adoption. Therefore, insurtech adoption mediates the relationship between digital literacy and insurance inclusion.

6. Conclusions

This study sought to establish whether digital literacy and insurtech adoption can significantly influence insurance inclusion in Uganda. Also, the study sought to establish whether insurtech adoption mediates the digital literacy and insurance inclusion nexus. With the aid of PLS-SEM, we found significant positive effects of; digital literacy on insurance inclusion; insurtech adoption on insurance inclusion; and digital literacy on insurtech adoption. Furthermore, it was established that insurtech adoption mediates the digital literacy and insurance inclusion nexus The study confirms that digital literacy and insurtech adoption can influence insurance inclusion in the TAM context. To our knowledge, our study comes first in examining the mediating effect of insurtech adoption in the digital literacy and insurance inclusion nexus. More still, our study is the first to examine the effect of digital literacy and insurtech adoption on insurance inclusion. Previous studies have examined the influence digital financial literacy and fintech on financial inclusion. Yet, when insurance inclusion is not addressed, attainment of full financial inclusion will remain glim. Therefore, our study’s novelty lies in establishing how digital literacy and insurtech adoption interplay to influence insurance inclusion in the Ugandan context.

The findings of this study are significant for policy makers, insurance providers and development partners alike. As such, it is recommended that in addition to the tradition financial literacy programmes, policy makers should include the aspect digital financial literacy. The Bank of Uganda should revise the national financial inclusion strategy to include a digital literacy training agenda in the framework. The current strategy focuses of financial literacy yet without digital literacy, plausibility of the programme may not suffice in the wake of digital financial products and services. Additionally, as insurance providers role out insurtech, they should consider extending digital insurance literacy training to enhance insurance inclusion through digital insurance platforms. Furthermore, insurance providers and insurtech startups should design seamless and user-friendly insurtechs to encourage insurtech adoption for insurance inclusion.

Notwithstanding, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, the current study was a conducted in a developing country with an underdeveloped insurance market and with low technological advancement. This may affect generalisation of the study findings. Therefore, future studies could be done from a developed economy’s perspective. Furthermore, this study was cross-sectional and quantitative. Future studies could adopt longitudinal designs with mixed methods approaches to gather deeper insights on how digital literacy and insurtech adoption interplay to influence insurance inclusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and A.B.S.; methodology, A.K.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K. and A.B.S; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, A.K.; resources, A.K. and A.B.S; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and A.B.S; visualization, A.K. and A.B.S; supervision, A.B.S.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1: Study measurement items

| Digital literacy |

| Knowledge |

| KNW1 |

I know how to use digital devices such as smart phones, computers and tablets. |

| KNW2 |

I aware of threats and risks associated with online services. |

| KNW3 |

I know the importance of digital securities such as having strong passwords. |

| Skills |

| SKL1 |

I can ably navigate and search for information on the internet |

| SKL2 |

I can ably evaluate credibility of online information |

| Insurtech adoption |

| Perceived ease of use |

| PEU1 |

I find digital insurance platforms easy to use. |

| PEU2 |

I easily learn to use digital insurance platform. |

| PEU3 |

I am confident when using digital insurance platforms. |

| PEU4 |

The interface of the digital insurance platform is friendly. |

| PEU5 |

I easily learnt how to use the digital insurance platform |

| Perceived Usefulness |

| PUS1 |

Digital insurance platform made purchasing insurance easy. |

| PUS2 |

I easily monitor my insurance policy on the digital insurance

platform. |

| PUS3 |

Digital insurance has made the insurance process efficient. |

| PUS4 |

The digital platform has increased transparency of the insurance

provider. |

| PUS5 |

Overall, the digital insurance platform has improved my

experience with the insurance provider. |

| Insurance inclusion |

| Access |

| ACS1 |

Digital

insurance platforms provide convenient access to insurance products and

services. |

| Usage |

| USG1 |

I

intend to continue using digital insurance services. |

| USG2 |

I

would recommend others to buy insurance using digital platforms. |

| USG3 |

The

digital insurance platforms has a wide variety of insurance products and

services |

| USG5 |

I

feel good about my decision to buy insurance through a digital platform. |

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2000). “Attitudes and the attitude-behaviour relation: Reasoned and automatic processes.” European Review of Social Psychology, Vol. 11 No.1, pp. 1-33. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M., Khan, M. N., Tiwari, S., Wani, S. K., & Alam, F. (2023). “The impact of fintech and digital financial services on financial inclusion in India.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management, Vol. 16 No.22, pp.122. [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2020). “Insurance policy thresholds for economic growth in Africa.” European Journal of Development Research, Vol. 32 No.3, pp. 672-689. [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y., Dan Gavriletea, M., & Danuletiu, D. C. (2021). “Does the insurance sector really matter for economic growth? Evidence from Central and Eastern European countries.’ Journal of Business Economics and Management, Vol. 22 No.3, pp. 695-713. [CrossRef]

- Beck, T. (2020). Fintech and financial inclusion: Opportunities and pitfalls. Asian Development Bank Institute. Retrieved from Social Science Premium Collection. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2487312988.

- Bittini, J. S., Rambaud, S. C., Pascual, J. L., & Moro-Visconti, R. (2022). “Business models and sustainability plans in the FinTech, Insurtech, and Prop Tech industry: Evidence from Spain.” Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), Vol. 14 No.19. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R., Troshani, I., Rao Hill, S., & Hoffmann, A. (2022). “Towards an understanding of consumers’ FinTech adoption: The case of open banking.” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol 40. No.4, pp. 886-917. [CrossRef]

- Cheston, S., Kelly, S., McGrawth, A., French, C., & Ferenzy, D. (2018). Insurance inclusion: Closing the protection gap for emerging customers. Center for Financial Inclusion.

- Cruijsen, C. V., Haan, J. D., & Roerink, R. (2019). “Financial knowledge and trust in financial institutions.” DNB Working Paper, No.662. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology.” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No.3, pp. 319-340. [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The global findex database 2021. Chicago: World Bank Publications. [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global findex database 2017 (1st ed. ed.). Washington, D. C: World Bank Publications. [CrossRef]

- Elkaseh, A. M., Wong, K. W., & Fung, C. C. (2016). “Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of social media for e-learning in Libyan higher education: A structural equation modelling analysis.” International Journal of Information and Education Technology, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Finscope. (2018). Finscope survey: Top line findings summary report. Kampala: Financial Sector Deepening Uganda.

- Gautum, R., Singh, & Kanoujiya, J. (2022). “Role of regional rural banks in rural development and its influences on digital literacy in India.” IRE Journals, Vol.5 No.12.

- Gie, T. A., & Fenn Chung Jee. (2019). “Technology acceptance model and digital literacy of first-year students in a private institution of higher learning in Malaysia.” Berjaya Journal of Services & Management, Vol. 11, pp 103-116. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (Eighth edition ed.). Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Hassan, Ashfaq, M., Parveen, T., & Gunardi, A. (2022). “Financial inclusion – does digital financial literacy matter for women entrepreneurs.” International Journal of Social Economics. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-04-2022-0277. [CrossRef]

- Holliday, S. (2019). How insurtech can close the protection gap in emerging markets International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10986/32366.

- International Association of Insurance Supervisors. (2022, Dec 16,). IAIS global insurance market report 2022 highlights key risks and trends facing the global insurance sector. Targeted News Service. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2754850078.

- Jang, M., Aavakare, M., Nikou, S., & Kim, S. (2021). “The impact of literacy on intention to use digital technology for learning: A comparative study of Korea and Finland.” Telecommunications Policy, Vol. 45 No.7. [CrossRef]

- Kabakus, A. K., Bahcekapili, E., & Ayaz, A. (2023). “The effect of digital literacy on technology acceptance: An evaluation on administrative staff in higher education.” Journal of Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515231160028. [CrossRef]

- Kanga, D., Oughton, C., Harris, L., & Murinde, V. (2022). “The diffusion of fintech, financial inclusion and income per capita.” The European Journal of Finance, Vol. 28 No.1, pp. 108-136. [CrossRef]

- Kass-Hanna, J., Lyons, A. C., & Liu, F. (2022). “Building financial resilience through financial and digital literacy in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.” Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 51. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Zoo, H., Lee, H., & Kang, J. (2018). “Mobile financial services, financial inclusion, and development: A systematic review of academic literature.” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, Vol. 84 No. 5. [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, A., & Sibindi, A. B. (2023). “Insurance inclusion in Uganda: Impact of perceived value, insurance literacy and perceived trust.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management, Vol. 16 No.2, pp. 81. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., & Chen, C. (2020). “The promise and perils of Insurtech.” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, (2020), pp. 115-142.

- Lyons, A. C., & Kass-Hanna, J. (2021). “A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy.” Financial Planning Review (Hoboken, N.J.), Vol. 4 No.2. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A., Kass-Hanna, J., & Greenlee, A. (2020). Impacts of financial and digital inclusion on poverty in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Mikheev, A., Serkina, Y., & Vasyaev, A. (2023). “Current trends in the digital transformation of higher education institutions in Russia.” Education and Information Technologies, Vol. 26, pp. 4537–4551. [CrossRef]

- Moenjak, T., Kongprajya, A., & Monchaitrakul, C. (2020). FinTech, financial literacy, and consumer saving and borrowing: The case of Thailand. Asian Development Bank Institute. Retrieved from Social Science Premium Collection Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2423771629.

- Mohammadyari, S., & Singh, H. (2015). “Understanding the effect of e-learning on individual performance: The role of digital literacy.” Computers and Education, Vol. 82, pp. 11-25. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P., Trinh, L., & Huang, B. (2019). The need to promote digital financial literacy for the digital age. International Monetary Fund.

- Nikou, S., & Aavakare, M. (2021). “An assessment of the interplay between literacy and digital technology in higher education.” Education and Information Technologies, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 3893-3915. [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S., De Reuver, M., & Mahboob Kanafi, M. (2022). “Workplace literacy skills—how information and digital literacy affect adoption of digital technology.” Journal of Documentation, Vol. 78 No. 7, pp. 371-391. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, H., Meghwal, D., & Dayama, V. (2018). “Digital financial literacy: A study of households of Udaipur.” Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 5, pp. 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, R., Ali, S., Aulia, A., & Hidayah, R. (2022). “The current digital financial literacy and financial behaviour in Indonesian millennial generation.” Journal of Accounting and Investment, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 78-94. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chaudhary, K. (2020). “Digital literacy: A review of literature.” International Journal of Techno ethics, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 65-94. [CrossRef]

- Rosyadah, K., Budiandriani, B., & Hasrat, T. (2021). “The role of fintech: Financial inclusion in MSMEs (case study in Makassar city).” Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 268-275. [CrossRef]

- Sahay, R. (2020). The promise of fintech. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund.

- Setiawan, M., Effendi, N., Santoso, T., Dewi, V. I., & Sapulette, M. S. (2022). “Digital financial literacy, current behavior of saving and spending and its future foresight.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 320-338. [CrossRef]

- Sibindi, A. B. (2022). “Information and communication technology adoption and life insurance market development: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management, Vol. 15 No. 12, pp. 568. [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U., MohY-Ul-Din, S., Abu-Rumman, A., Al-Shraah, A. E. M., & Ahmed, I. (2020). “Insurance-growth nexus: Aggregation and disaggregation.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, Vol 7 No.12, pp. 665-675. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Liu, C., & Lan, S. (2022). “Digital literacy and financial market participation of middle-aged and elderly adults in China.” Economic and Political Studies, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), pp. 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. (1973). Statistics (3. ed., 1. print. ed.). Harper & Row.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity.

| Variables |

Composite Reliability |

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

Content Validity Index (CVI |

| Digital Literacy |

0.878 |

0.673 |

0.750 |

| Insurtech Adoption |

0.922 |

0.590 |

0.800 |

| Insurance Inclusion |

0.873 |

0.671 |

0.833 |

Table 2.

Multicollinearity and Discriminant Validity.

Table 2.

Multicollinearity and Discriminant Validity.

| Variables |

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) |

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) |

| Insurance Inclusion <-> Digital Literacy |

0.601 |

1.394 |

| Insurtech Adoption -> Insurance Inclusion |

0.590 |

1.000 |

| Digital Literacy -> Insurtech Adoption |

0.756 |

1.394 |

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics.

| |

Frequency |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

| Male |

168 |

42.9 |

| Female |

223 |

57.1 |

| Total |

391 |

100 |

| Age |

|

|

| 18-33 years |

179 |

45.7 |

| 34-49 years |

194 |

49.7 |

| 50-65 years |

18 |

4.6 |

| Total |

391 |

100.0 |

| Education Level |

|

|

| Primary Leaving Examination (PLE) |

0 |

0 |

| Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) |

10 |

2.6 |

| Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) |

20 |

5.1 |

| Diploma |

57 |

14.6 |

| Degree |

257 |

65.7 |

| Masters |

42 |

10.7 |

| PhD |

5 |

1.3 |

| Total |

391 |

100 |

| |

Frequency |

% |

| Gadget Used to Access insurance |

|

|

| Mobile Phone |

358 |

91.6 |

| Computer |

33 |

8.4 |

| Total |

391 |

100 |

Table 4.

Correlation results.

Table 4.

Correlation results.

| |

Digital Literacy |

Insurtech Adoption |

Insurance Inclusion |

| Digital Literacy |

1.000 |

|

|

| Insurtech Adoption |

0.532** |

1.000 |

|

| Insurance Inclusion |

0.525** |

0.683** |

1.000 |

Table 5.

Hypothesis results.

Table 5.

Hypothesis results.

| Hypothesised path |

Path coefficient

|

Standard dev.

|

t-values

|

P values

|

Decision |

Digital Literacy -> Insurance Inclusion

|

0.226

|

0.057

|

3.940 |

0.000 |

Supported |

Insurtech Adoption -> Insurance Inclusion

|

0.563 |

0.045 |

12.634 |

0.000 |

Supported |

Digital Literacy -> Insurtech Adoption

|

0.532 |

0.039 |

13.526 |

0.000 |

Supported |

Digital Literacy -> Insurtech Adoption -> Insurance Inclusion

|

0.299 |

0.034 |

8.884 |

0.000 |

Supported |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).