1. Introduction

Online news, is characterized by quickness, multimedia and interaction. Online news make recipients know quickly the news events happening around the world and see more news content or information that conforms to their existing attitudes and hidden prejudices. In recent years, the Internet and social media have developed rapidly. By December 2022, the number of netizens in China reached 1.067 billion, and the Internet penetration rate reached 75.6%. With the rapid development of the internet and social media, application software such as TikTok gradually changed from entertainment platforms to information platforms with a new nature and has become essential channels for netizens to obtain news. Therefore, the online news belief has become an important social issue and academic focus.

In research fields on the believability of online news, a common method employed is the News Evaluation Task. This method randomly presents participants with a set of real and fake news headlines. Participants are required to read each news item and assess its believability or authenticity by assigning Likert scale scores [

11,

19,

21,

31,

37].

News belief involves complex cognitive processing, and it has been mainly explored from two aspects: the characteristics of news and individual differences in recipients. With regard to the characteristics of news, the main results was that the higher the credibility source [

39,

40] and the greater familiarity [

21,

41] of the news, the more accurately participants perceived its believability. Concerning individual differences, previous research has found that differences in many traits may affect the news belief, such as personality [

1,

2,

41,

42,

43,

44], thinking style [

3,

4,

31,

45], media literacy [

48,

49,

50] and prior attitudes [

5,

6,

46,

47].

The emotional contagion theory posits that emotional sharing between individuals forms the basis of empathy [

7]. Individuals with strong empathic abilities were found to have strong emotional sharing abilities [

8]. We, therefore, speculated that individuals with high trait empathy might have a stronger ability to share emotions, which made them more likely to develop immersive understanding and resonance with news content and to believe in online news content. In other words, an individual’s trait of empathy might influence their belief in online news. However, to date, little attention has been devoted to the impact of empathy on online news belief and its internal processes. This study focused on the role of empathy in the online news belief. It aimed to address the following questions: Firstly, would individual differences in trait empathy influence news belief? Secondly, if so, what would be the internal processes behind this influence?

1.1. Trait Empathy and the Online News Belief

Trait empathy (TE) refers to “the ability to share the feelings and experiences of others by imagining their situation”[

9]. It is a stable personality trait and holds significant social functions, making it a focal point of research in psychology. Cognitive empathy (CE) and affective empathy (AE) are the two primary components of it. CE refers to the ability to engage in cognitive role-taking or the cognitive processes involved in adopting the psychological perspective of others. AE involves responding emotionally to the experiences observed in others or sharing the feelings of a companion [

10].

Limited existing research suggested that TE may influence online news beliefs. For example, Martel et al. [

11] found that a higher level of emotional arousal before reading news predicted greater belief in fake (rather than real) news. Although this study did not directly measure individual TE, its emotional indicators were somewhat related to individual TE, in which the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale was used to assess participants’ emotional state before reading news. Preston et al. [

12] found that participants with higher emotional intelligence (Attending to Emotions, Emotion-Based Decision-Making, and Empathic Concern) were less likely to be misled by fake news. However, their fake news detection task combined judgments of objectivity, professionalism, argument strength, and belief in the items. This novel and comprehensive fake news detection task might unintentionally engage participants’ analytical thinking, which could directly influence the believability of news [

3,

6,

31,

41]. In many real-world situations, recipients are unlikely to engage in this kind of analytical thinking when encountering fake news. Furthermore, they did not explicitly separate the roles of two different components of empathy in the news belief. Therefore, more experimental evidence is needed to elucidate the relationship between empathy and online news belief.

This study directly investigated the impact of different components of TE on online news belief, using participants’ believability judgments of news as the primary measure. Given that affective empathy rather than cognitive empathy has frequently been found to be more relevant to people’s behaviors (such as prosocial behavior and moral decision-making) [

29,

30,

51], we proposed Hypothesis 1: an individual’s AE, rather than CE, would be related to his belief in online news. Specifically, higher scores in AE would be associated with higher belief in online news.

1.2. The Mediating Effect of State Empathy in Affective Empathy-the Believability of Online News

State empathy (SE) refers to the emotional response that individuals experience when imagining or observing the emotional state or circumstances of others [

13]. Empathy in daily life often occurs within specific contexts and is influenced by situational factors. Rusting [

14] suggested that the influence of TE on emotion processing is mediated by SE. meaning that SE allows TE to be expressed. The impact of TE on individual behavior is most evident when expressed in certain contexts. SE in specific situations or tasks might reflect either stimulus or task-induced state effects or more stable TE.

Research examining emotions has shown that emotional traits generally correlate positively with emotional states and generate a propensity to experience related emotional states [

15]. It was also demonstrated that emotions induced by news reading can influence belief [

5,

16]. For instance, Bago et al. [

16] asked participants to read 16 news headlines, which were categorized into four groups: fake news consistent with the Republican party, real news consistent with the Republican party, fake news consistent with the Democratic party, and real news consistent with the Democratic party. They then required participants to assess the authenticity of these headlines and report their emotional states while reading. The results indicated that emotional experiences during reading (excluding anger) diminished the believability of political news. Wang et al. [

17] uncovered a positive correlation between belief in misinformation about food safety and negative emotions, and negative emotion partially mediated the relationship between misinformation and the subsequent diffusion on social media and completely mediated the relationship between misinformation and the subsequent face-to-face diffusion among high-trust individuals.

Therefore, when investigating the relationship between TE and the belief in online news, it was essential to consider SE. Trait empathy might be expressed through state empathy, which directly influenced the believability of online news. We proposed Hypothesis 2: SE (characterized by emotional response following headline reading) would be related to the believability of online news. it would be expected that the SE would partially mediate the effects of AE on the belief in online news.

1.3. The Moderating Effect of News Type on Affective Empathy-State Empathy- the Belief in Online News

Though the results of Piksa et al. [

18] that those who believed the real news also believed the fake news suggested no relationship between belief and news type, more results support indirectly that belief may be influenced by the type of news. Studies focusing on individual differences have found that thinking style only affected the accuracy of perceived fake news but not the accuracy of perceived real news [

6,

19,

31,

45]. For instance, it was reported that more actively open-minded individuals and those showing more reflective and less intuitive thinking patterns considered fake news as less reliable, but these traits did not correlate with reaction scores to real news [

6]. Four groups of participants with varying susceptibility to (fake) information had more significant differences in their accuracy of perceiving real news than perceiving fake news [

18]. Moreover, studies examining factors influencing the believability of online news [

11,

20,

21,

52] or intervention methods [

37,

53,

54] have also observed similar type effects.

Furthermore, Bago et al. [

16] found no significant differences in emotional responses among participants reading real and fake news, but emotional experiences during reading weakened the belief in fake news more than real news. The moderating effect of news type was thus expected to occur in the relationship between SE and the belief in online news. Martel et al. [

11] found higher emotional arousal before news exposure predicted greater trust in fake (but not real) news. We thus proposed Hypothesis 3: The influence of SE on the belief in online news would be moderated by news type.

In conclusion, using a fake news detection task similar to Pennycook et al. [

21], the present study aimed to investigate the impact of TE on news belief and its internal processes. The participants’ TE scores, comprising CE and AE dimensions, would be assessed using the IRI-C scale. Participants would be instructed to read real and fake news and evaluate measures such as emotional response and believability for each news item. The news headlines would be presented in a format similar to online news, complete with headlines, images, and accompanying descriptive text. To ensure a content-independent understanding of the relationship between empathy and the belief in online news, the topics would encompass a wide range, including social issues, current events, and scientific knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Totally 149 undergraduates were recruited. After excluding 9 participants who did not complete all experiments diligently, 140 participants (47 males, 19.67 ± 2.16 years) were included. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and normal color vision. All participants signed an informed consent form and received payments for their participation. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Normal University (No. 2023091104).

2.2. Materials

There were 100 news headlines. Considering the interference of the experimental duration on the data quality, the 100 headlines were divided into two sets that matched valence (3.23 ± 1.24 vs. 3.01 ± 1.03,

t(49) = 1.103,

p = 0.275), arousal (4.09 ± 0.48 vs. 4.07 ± 0.50,

t(49) = 0.184,

p = 0.855), familiarity (3.22 ± 0.39 vs. 3.22 ± 0.41,

t(49) = -0.109,

p = 0.914), empathy (4.66 ± 0.54 vs. 4.75 ± 0.56,

t(49) = -1.158,

p = 0.252), and believability (5.17 ± 0.85 vs. 5.05 ± 0.68,

t(49) = 1.207,

p = 0.253). Each set included 25 real and 25 fake headlines, All fake news headlines were initially taken from a well-known Chinese fact-checking website (

https://www.piyao.org.cn/pysjk/frontsql.html). Real news headlines were selected from mainstream news sources (e.g.,

www.cctv.com). The materials were presented in the format of typical online news articles (including headlines, images, and descriptive text). The topics of the materials covered various aspects of social issues, current events, and general scientific knowledge. All news images were standardized to a size of 1250 × 780 pixels using Photoshop.

The IRI-C [

22] comprises 22 items and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (does not describe me well) to 4(describes me very well). Higher scores indicate a higher level of empathy. The scale is divided into four subscales: Perspective Taking (PT), Fantasy Scale (FS), Empathetic Concern (EC), and Personal Distress (PD). The PT and FS fall under CE, while EC and PD are related to AE. The Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.753.

2.3. Procedure

The experiments were programmed using E-prime software. The news was presented on the center of the computer screen in a pseudo-random order. The number of displays of real and false news headlines at the start was balanced among participants. Participants were instructed to read the content of each news thoroughly and then to report their feelings by pressing the number keys on the keyboard, which included their emotion response (1 – Can’t feel it at all; 7 – Can totally feel it), believability(1 – Extremely unbelievable; 7 – Extremely believable), valence(1 – Very negative; 4 – neural; 7 – Very positive), arousal(1 – Not at all; 7 – Extremely), familiarity(1 – Not at all; 7 – Extremely). The experiment lasted approximately 60 minutes with one break, after which IRI-C questionnaire data and demographic data were collected.

2.4. Data Analysis

(1) Descriptive statistics were employed for variables such as trait empathy, affective empathy, cognitive empathy, state empathy, and believability. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was utilized to calculate the relationships between these variables.

(2) The Influence of Affective Empathy on Believability of News: The Mediating Effect of State Empathy.

A mediation model was constructed to examine the mediating effect using data from all participants. The mediating effect was examined based on Hayes’s Bootstrap method [

23], using Hayes Process Macro 4.0 in SPSS 29, with a sample size of 5000 and a 95% confidence interval. In the model, AE served as the independent variable (X), belief in the news (believability) as the dependent variable (Y), valence as the control variable (S), and SE as the mediating variable (M).

(3) The moderating effects of news types on the mediating role of state empathy toward affective empathy and Believability

The analyses were conducted using SPSS 29 (IBM). A moderated mediation analysis was tested using Hayes Process Macro 4.0 in SPSS 29, with a sample size of 5000 and a 95% confidence interval. Affective empathy was served as the independent variable (X), perceived believability (believability) as the dependent variable (Y), state empathy as the mediating variable (M), valence as the control variable (S), and news type (fake news = 0, real news = 1) as the moderating variable (V). Additionally, simple slope tests were conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results and Correlation Analysis

Paired samples t-tests examined the differences in valence, arousal, and familiarity between real and fake news. It revealed that fake news had significantly lower valence compared to real news (2.80 ± 0.69 vs. 3.45 ± 1.39, t(49) = -4.12, p < 0.001), and fake news was similar to real news in arousal (4.04 ± 0.50 vs. 4.12 ± 0.47, t(49) = -1.06, p = 0.297), and familiarity (3.23 ± 0.50 vs. 3.21 ± 0.28, t(49) = 0.31,p = 0.758).

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that SE was positively correlated with TE, AE, and believability; TE was positively correlated with its AE component and CE component; believability was positively correlated with TE and AE; AE was positively correlated with CE. The other pairwise correlations are not significant. These results were presented in

Table 1.

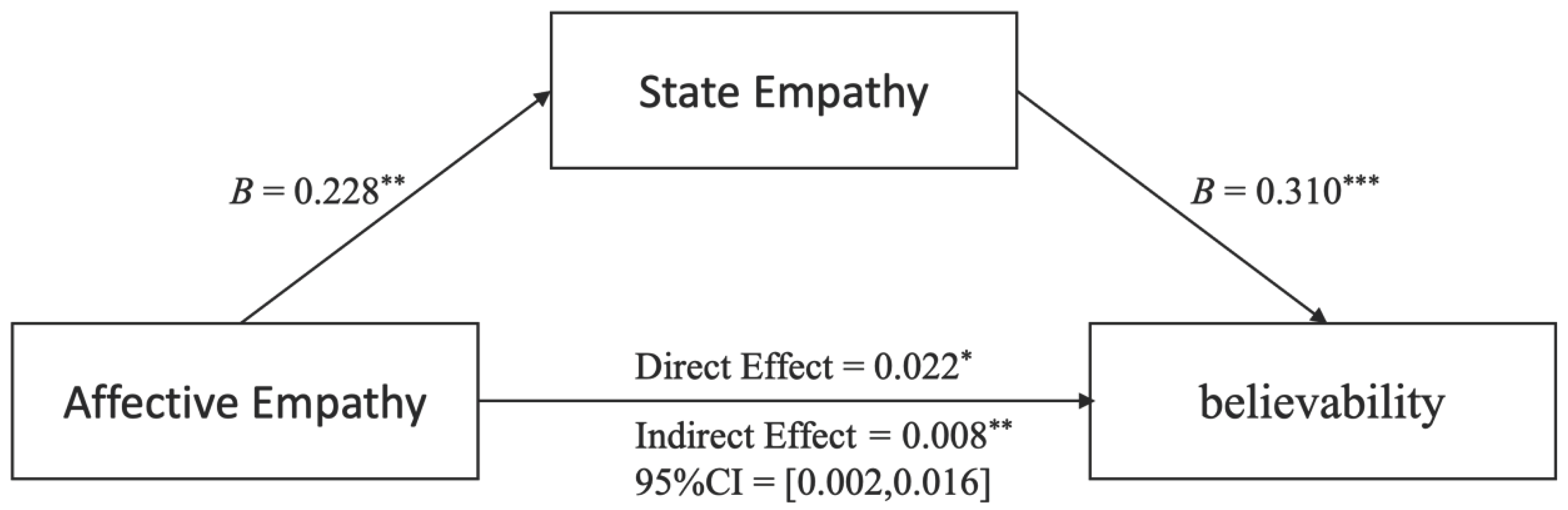

3.2. The Influence of Affective Empathy on News Beliefs: The Mediate Effect of State Empathy

As

Figure 1 shows, the results supported the hypothesis: SE partially mediated the influence of AE on news believability. The mediation test’s indirect effect did not include zero (Effect = 0.008, SE = 0.004, 95%CI = [0.002, 0.016]). Furthermore, after controlling for the mediator variable state empathy, the direct effect was significant, with the confidence interval not including zero (Effect = 0.022, SE = 0.009, 95%CI = [0.004, 0.040]).

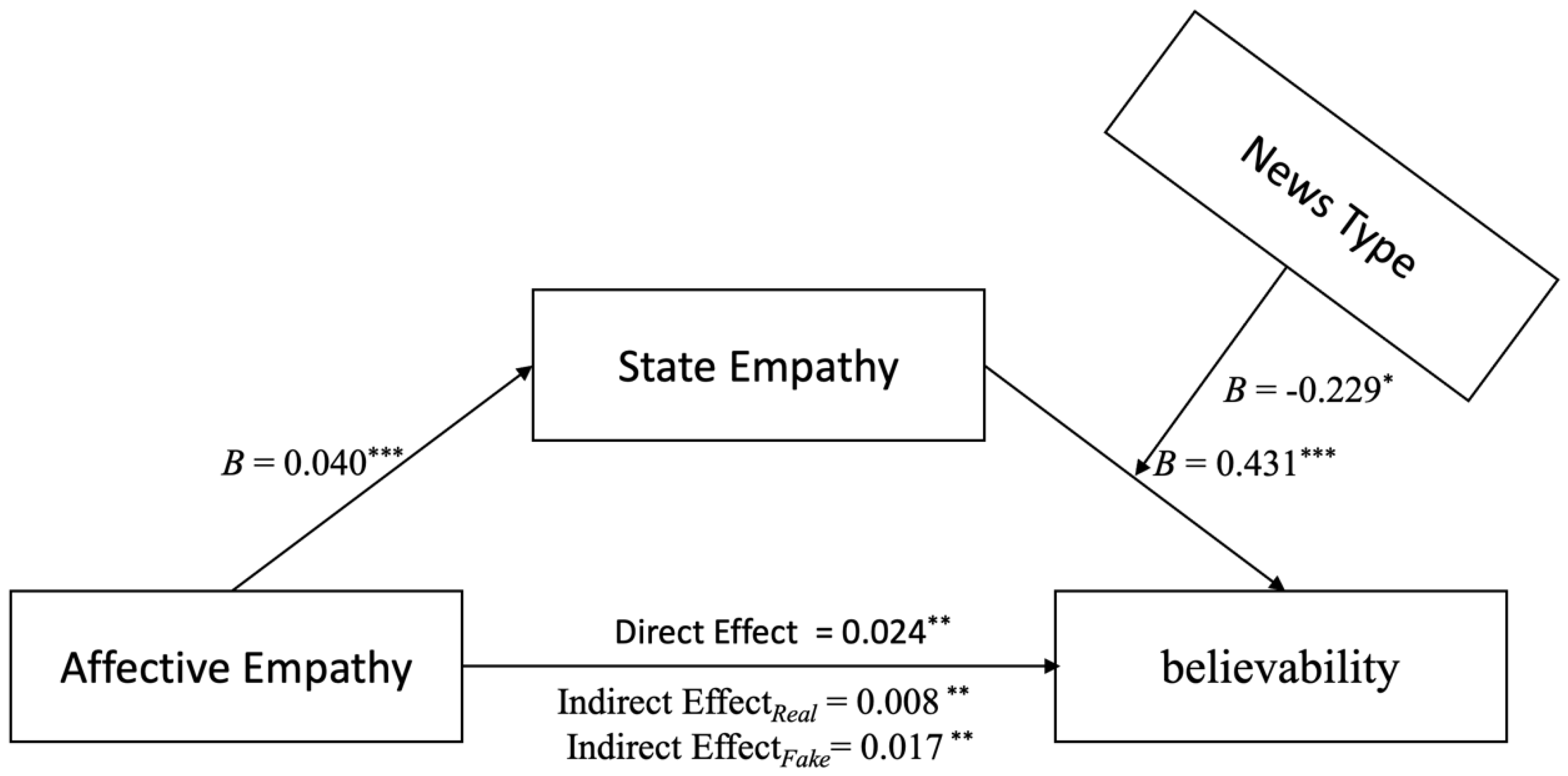

3.3. The Moderating Effects of News Types on the Mediating Role of State Empathy toward Affective Empathy and Believability

Statistical analysis showed that in the influence of AE on believability, the mediating role of news types in the path of AE affecting SE was not valid (

Index = -0.002,

SE = 0.007, 95%CI = [-0.015, 0.011]). But, news types had a mediating effect on the path of SE affecting belief in the influence of AE on believability. The model index does not include zero (

Index = -0.009,

SE = 0.005, 95% CI = [-0.019, -0.001]), thus indicating a valid moderated mediation effect. As shown in

Figure 2.

Table 2 presented the mediation effects and bootstrap confidence intervals for different levels of the moderating variable (news type) in the relationship between AE and believability. The results indicated that SE partially mediated the influence of AE on believability both real and fake news.

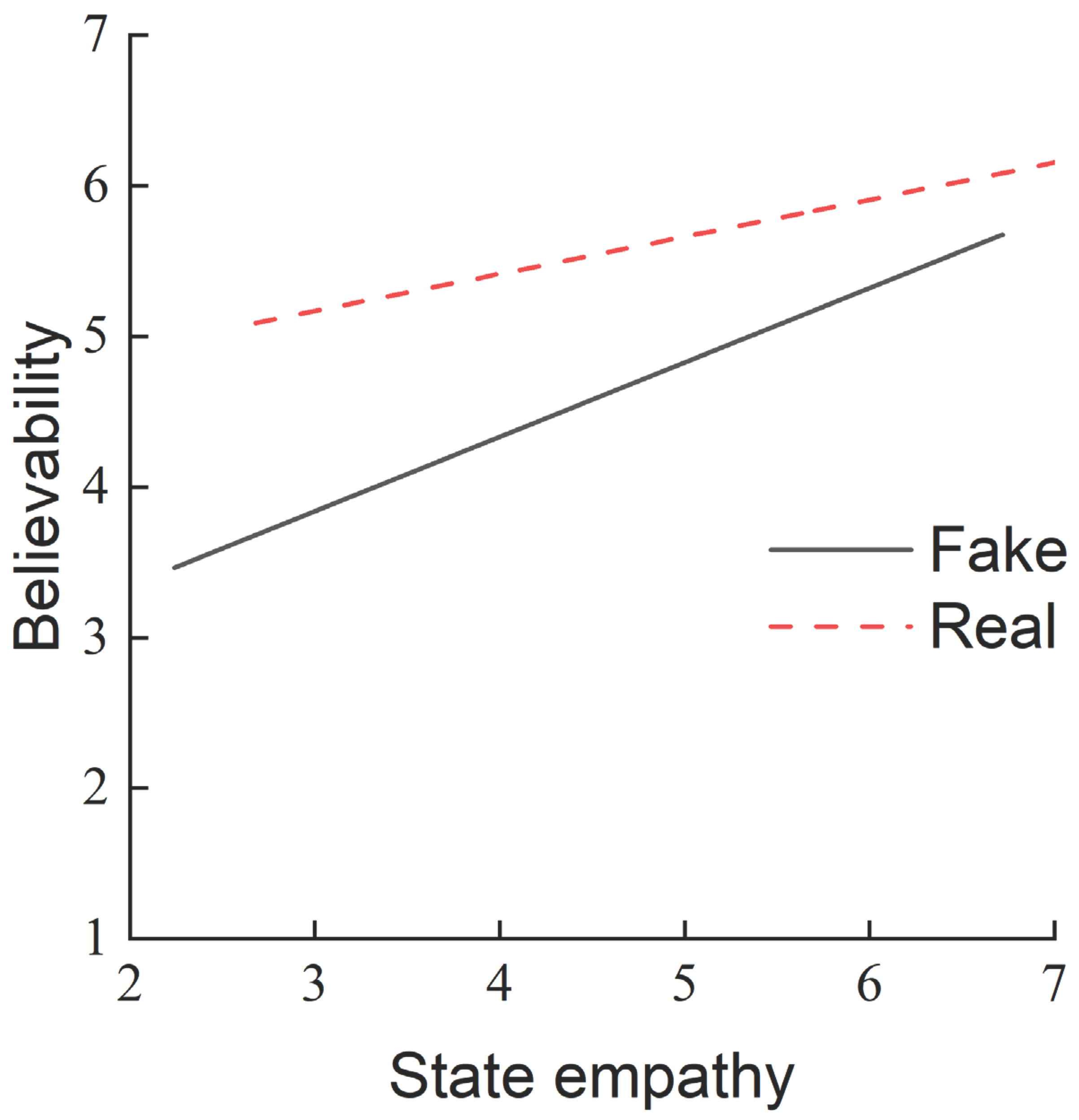

To further analyze the interaction effect between news type and state, simple slope tests were conducted to calculate separate effect values of news type “real” and “fake.” The results are illustrated in

Figure 3. Higher state empathy towards a news article is associated with higher believability. The SE predicted believability under “real” and “fake” news conditions. However, the predictive effect of SE on believability was significantly greater in the “fake” news condition (

b = 0.431) compared to the “real” news condition (

b = 0.202).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between TE and the belief in online news and the mediating and moderating roles of state empathy and news type in that relationship. The results revealed that state empathy mediated the relationship between AE and belief in online news, and the news types played a moderating role in it.

4.1. The Influence of Trait Empathy on the Believability of News

The influence of TE on cognition has been extensively studied [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. For instance, using a dot-probe paradigm and eye-tracking technique to investigate the attention bias towards happy faces and positive words in participants with high and low empathy, Liu et al. [

55] found that trait empathy influenced the processing of emotional information. However, few studies addressed questions about the impact of TE on the belief in online news. This study found that the AE rather than CE within TE positively correlated with the belief in online news, supporting hypothesis 1.

CE and AE are two different components of TE, reflecting different aspects of an individual’s empathetic abilities, and they have different neural bases [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. It is reasonable that they have different effects on the belief in online news. Previous studies have also found that people’s behavior (e.g., altruistic behavior and moral decision-making) is more influenced by AE rather than CE [

29,

30]. For example, Herne et al. [

30] found that, within TE subscales, only the AE subscale was positively associated with dictator game-giving. The predictive effect of age and gender on altruistic moral decision-making was influenced by AE rather than CE [

51]. Our finding separated the roles of CE and AE in the belief in online news. The internal processes through which AE influences the belief in online news might be related to thinking styles. It was found that the performance of rational thinking was related to the news belief [

3,

6,

31]. The dual-process model of empathy posits that CE is a more rational process, while AE is less rational [

32,

62]. For instance, Martingano et al. [

33] measured empathy using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), measured the tendency for rational thinking using the Need for Cognition Scale (NFC) and assessed the performance of rational thinking using the Cognitive Reflection Task (CRT). The results revealed a complex relationship between empathy and rational thinking, depending on how rationality (the tendency for rational thinking or the performance of rational thinking) and empathy (affective empathy or cognitive empathy) were measured. Nevertheless, the performance of rational thinking and affective empathy exhibited a significant negative correlation, while the correlation between the performance of rational thinking and cognitive empathy was insignificant.

In conclusion, individuals with strong AE may prefer less rational thinking [

33,

34,

61]. Thus, individuals with high AE are more likely to believe fake news.

4.2. The Mediating Effect of State Empathy

In the impact of AE on news belief, it was found that empathy partially mediated this relationship, elucidating the internal process of how AE influences news belief, thus confirming hypothesis 2. Specifically, individuals with higher AE exhibited higher levels of SE in the task context, leading to higher belief in news.

There is limited research on the relationship between SE and the belief in online news. Generally, this result was consistent with a few existing studies, particularly those using political news as their material [

5,

16]. Rijo and Waldzus [

5] presented participants with five real and five fake news headlines extracted from Facebook, all related to political content, and asked them to judge the believability of these headlines. The participants also had to answer questions related to their political beliefs. The results showed that the believability of the news was influenced by the emotional reactions

of participants with different political beliefs during headline reading. Negative beliefs about the political system increased emotional reactions to both real and fake news and subsequently enhanced the believability of the news, accuracy categorization, and willingness to share the news. Their findings highlighted the relationship between individual differences in political beliefs, specific types of emotional responses, and the belief in political news. The present study revealed a relationship between individual differences in TE, SE, and the belief in non-political news, the conclusion of which may be more generalizable.

4.3. The Moderating Effect of News Type

Furthermore, the present study revealed that news type moderated the SE’s effects on belief. Specifically, SE significantly predicted the belief of both real and fake news, but with a more significant effect on the belief in fake news. It is suggested that individuals with high AE are easier to believe the news, especially fake news, partially because they are more likely to be emotionally responsive when reading the news.

Although previous research did not explicitly investigate the moderating role of news type in online news belief, many studies focused on fake news have found that certain factors have different impacts on the belief in different news types [

36,

37], as mentioned in the Introduction. For instance, Calvillo et al. [

37] investigated the impact of truthiness cues on the believability of news and found that truthiness cues effectively reduced the repetition effect in the believability of fake news, with news type playing a significant moderating role. Martel et al. [

11] found that specific emotions (such as interest, excitement, fear, tension, etc.) before reading news headlines significantly predicted higher belief in fake (but not real) news. Additionally, compared to a control induction or a reason induction, an emotion induction led to higher belief in fake but not real news. From the perspective of empathy, our study clarified the role of news type in the news belief, elucidating how news type moderated the AE - SE - news belief.

Besides, our study found that SE predicted the believability of fake news to a greater extent than that of real news. This indicated that empathy has a more substantial influence on the believability of fake news, with highly empathetic individuals being more likely to trust fake news. In real-life contexts, fake news often carries a higher emotional charge. According to the theory of emotional economics, fake news creators intentionally write stories that evoke emotions to gain attention and generate revenue on social media platforms [

35]. Most emotions in news articles show statistically significant differences between real and fake news [

63]. Therefore, individuals with high affective empathy should be cautious when using social media, particularly with emotionally charged news, and consciously evaluate the believability of news content that triggers empathy.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

However, there are still some limitations in the present study. First, caution is needed when extrapolating our results. Our participants were native Chinese, and the number of male participants was lower than that of females. There can be cultural and gender differences in both emotional response and belief in online news. Second, there is a lack of direct evidence for our thinking style to explain the effect of AE on belief. Future studies should include a Cognitive Reflection Test [

38] to investigate the relationship between empathy, analytical thinking, and belief in online news.

Additionally, Future research can expand upon the current findings in several ways: 1. Neuroscientific Investigations: Incorporate functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to examine the neural basis of the relationship between empathy and believability of online news. This can provide objective evidence at the neural level regarding how affective empathy, rather than cognitive empathy, influences the believability of online news. 2. As this study has highlighted the crucial role of empathy in the believability of online news, future research can explore related variables such as an individual’s self-construal orientation or the context of the news situation (e.g., whether the subject belongs to an in-group or an out-group). Exploring these factors may reveal new insights. 3. Drawing an analogy to research on initial trust, investigate factors that influence the believability of online news. Research in this area could explore cognitive resources, intergroup interaction contexts, and more macro-level factors. This broader perspective may uncover new dimensions of influence. 4. In this study, valence was included as a covariate but not examined as an independent variable. Future research could independently manipulate valence to explore its direct impact on news belief, providing supplementary evidence. These suggested avenues of research can further enrich our understanding of how empathy and related factors influence the believability of online news in the digital age.

5. Conclusions

Affective empathy, rather than cognitive empathy, influenced the believability of online news.

Within the impact of affective empathy on news believability, state empathy acted as a partial mediator

News type moderated the state empathy’s effects on belief, and state empathy predicted the belief in fake news to a greater extent than that of real news. Our findings shed light on the influence of empathy on the believability of online news and its internal processes and provide a possible strategy to reduce belief in fake news. It suggested that individuals with high levels of affective empathy may be more susceptible to the influence of fake news, particularly when faced with news that elicits high levels of state empathy. It underscores the importance of discerning the authenticity of news, especially when exposed to high-state empathetic news.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yifan Yu; Data curation, Yifan Yu, Shizhen Yan and Zhenzhen Xu; Formal analysis, Yifan Yu, Shizhen Yan and Qihan Zhang; Investigation, Yifan Yu and Zhenzhen Xu; Methodology, Yifan Yu, Shizhen Yan and Qihan Zhang; Project administration, hua jin; Resources, Yifan Yu and Zhenzhen Xu; Software, Yifan Yu; Supervision, hua jin; Validation, Yifan Yu, Qihan Zhang and Guangfang Zhou; Visualization, Yifan Yu; Writing – original draft, Yifan Yu; Writing – review & editing, Qihan Zhang, Guangfang Zhou and hua jin.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Normal University (No. 2023091104).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

All authors disclosed no relevant relationships. The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Calvillo, Dustin P., Ryan JB Garcia, Kiana Bertrand, and Tommi A. Mayers. “Personality factors and self-reported political news consumption predict susceptibility to political fake news.” Personality and individual differences 174 (2021): 110666. [CrossRef]

- Escolà-Gascón, Álex, Neil Dagnall, Andrew Denovan, Kenneth Drinkwater, and Miriam Diez-Bosch. “Who falls for fake news? Psychological and clinical profiling evidence of fake news consumers.” Personality and Individual Differences 200 (2023): 111893. [CrossRef]

- Ross, Robert M., David G. Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. “Beyond “fake news”: Analytic thinking and the detection of false and hyperpartisan news headlines.” Judgment and Decision making 16, no. 2 (2021): 484-504.

- Newton, Christie, Justin Feeney, and Gordon Pennycook. “On the disposition to think analytically: Four distinct intuitive-analytic thinking styles.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (2023): 01461672231154886. [CrossRef]

- Rijo, Angela, and Sven Waldzus. “That’s interesting! The role of epistemic emotions and perceived credibility in the relation between prior beliefs and susceptibility to fake-news.” Computers in Human Behavior 141 (2023): 107619.

- Saltor, Joan, Itxaso Barberia, and Javier Rodríguez-Ferreiro. “Thinking disposition, thinking style, and susceptibility to causal illusion predict fake news discriminability.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 37, no. 2 (2023): 360-368. [CrossRef]

- Decety, Jean, and Jessica A. Sommerville. “Shared representations between self and other: a social cognitive neuroscience view.” Trends in cognitive sciences 7, no. 12 (2003): 527-533. [CrossRef]

- Decety, Jean, and Claus Lamm. “Human empathy through the lens of social neuroscience.” The scientific World journal 6 (2006): 1146-1163. [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Yoshiya, Jean Decety, Takashi Ohnishi, Motonari Maeda, Takeyuki Mori, Kiyotaka Nemoto, Hiroshi Matsuda, and Gen Komaki. “Empathy and judging other’s pain: an fMRI study of alexithymia.” Cerebral Cortex 17, no. 9 (2007): 2223-2234.

- Dvash, Jonathan, and Simone G. Shamay-Tsoory. “Theory of mind and empathy as multidimensional constructs: Neurological foundations.” Topics in Language Disorders 34, no. 4 (2014): 282-295.

- Martel, Cameron, Gordon Pennycook, and David G. Rand. “Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news.” Cognitive research: principles and implications 5 (2020): 1-20.

- Preston, Stephanie, Anthony Anderson, David J. Robertson, Mark P. Shephard, and Narisong Huhe. “Detecting fake news on Facebook: The role of emotional intelligence.” Plos one 16, no. 3 (2021): e0246757. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Martin L. “Toward a comprehensive empathy-based theory of prosocial moral development.” (2001).

- Rusting, Cheryl L. “Personality, mood, and cognitive processing of emotional information: three conceptual frameworks.” Psychological bulletin 124, no. 2 (1998): 165.

- Rusting, Cheryl L. “Interactive effects of personality and mood on emotion-congruent memory and judgment.” Journal of personality and social psychology 77, no. 5 (1999): 1073.

- Bago, Bence, Leah R. Rosenzweig, Adam J. Berinsky, and David G. Rand. “Emotion may predict susceptibility to fake news but emotion regulation does not seem to help.” Cognition and Emotion 36, no. 6 (2022): 1166-1180. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Rui, Yuan He, Jing Xu, and Hongzhong Zhang. “Fake news or bad news? Toward an emotion-driven cognitive dissonance model of misinformation diffusion.” Asian Journal of Communication 30, no. 5 (2020): 317-342. [CrossRef]

- Piksa, Michal, Karolina Noworyta, Jan Piasecki, Pawel Gwiazdzinski, Aleksander B. Gundersen, Jonas Kunst, and Rafal Rygula. “Cognitive Processes and Personality Traits Underlying Four Phenotypes of Susceptibility to (Mis) Information.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 13 (2022): 1142. [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, Michael V., Gordon Pennycook, Adam Bear, David G. Rand, and Tyrone D. Cannon. “Belief in fake news is associated with delusionality, dogmatism, religious fundamentalism, and reduced analytic thinking.” Journal of applied research in memory and cognition 8, no. 1 (2019): 108-117.

- Smelter, Thomas J., and Dustin P. Calvillo. “Pictures and repeated exposure increase perceived accuracy of news headlines.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 34, no. 5 (2020): 1061-1071. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, Tyrone D. Cannon, and David G. Rand. “Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news.” Journal of experimental psychology: general 147, no. 12 (2018): 1865. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Feng-feng, Yi Dong, and Kai Wang. “Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index-C.” Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology (2010).

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Michael Scharkow. “The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter?.” Psychological science 24, no. 10 (2013): 1918-1927.

- Urbanska, Karolina, Shelley McKeown, and Laura K. Taylor. “From injustice to action: The role of empathy and perceived fairness to address inequality via victim compensation.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 82 (2019): 129-140. [CrossRef]

- de Jesús Cardona-Isaza, Arcadio, Saray Velert Jiménez, and Inmaculada Montoya-Castilla. “Decision-making styles in adolescent offenders and non-offenders: Effects of emotional intelligence and empathy.” Anuario de Psicología Jurídica 32, no. 1 (2022): 51-60.

- Liu, Ping, Juncai Sun, Wenhai Zhang, and Dan Li. “Effect of empathy trait on attention to positive emotional stimuli: evidence from eye movements.” Current Psychology (2020): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Borghi, Olaf, Lukas Mayrhofer, Martin Voracek, and Ulrich S. Tran. “Differential associations of the two higher-order factors of mindfulness with trait empathy and the mediating role of emotional awareness.” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 3201. [CrossRef]

- Butera, Christiana D., Laura Harrison, Emily Kilroy, Aditya Jayashankar, Michelle Shipkova, Ariel Pruyser, and Lisa Aziz-Zadeh. “Relationships between alexithymia, interoception, and emotional empathy in autism spectrum disorder.” Autism 27, no. 3 (2023): 690-703. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaomin, Yuqing Zhang, Zihao Chen, Guangcan Xiang, Hualing Miao, and Cheng Guo. “Effect of socioeconomic status on altruistic behavior in Chinese middle school students: mediating role of empathy.” International journal of environmental research and public health 20, no. 4 (2023): 3326. [CrossRef]

- Herne, Kaisa, Jari K. Hietanen, Olli Lappalainen, and Esa Palosaari. “The influence of role awareness, empathy induction and trait empathy on dictator game giving.” Plos one 17, no. 3 (2022): e0262196. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. “Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning.” Cognition 188 (2019): 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Martingano, Alison Jane. “A dual process model of empathy.” PhD diss., The New School, 2020.

- Martingano, Alison Jane, and Sara Konrath. “How cognitive and emotional empathy relate to rational thinking: empirical evidence and meta-analysis.” The Journal of Social Psychology 162, no. 1 (2022): 143-160. [CrossRef]

- Korkman, Hamdi, and Esra Tekel. “Mediating role of empathy in the relationship between emotional intelligence and thinking styles.” International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research 7, no. 1 (2020): 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Horner, Christy Galletta, Dennis Galletta, Jennifer Crawford, and Abhijeet Shirsat. “Emotions: The unexplored fuel of fake news on social media.” Journal of Management Information Systems 38, no. 4 (2021): 1039-1066. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sian, Joshua P. Forrest, Jessica Strait, Haeseung Seo, Dongwon Lee, and Aiping Xiong. “Beyond cognitive ability: Susceptibility to fake news is also explained by associative inference.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-8. 2020.

- Calvillo, Dustin P., and Thomas J. Smelter. “An initial accuracy focus reduces the effect of prior exposure on perceived accuracy of news headlines.” Cognitive research: principles and implications 5, no. 1 (2020): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Frederick, Shane. “Cognitive reflection and decision making.” Journal of Economic perspectives 19, no. 4 (2005): 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Heinbach, Dominique, Marc Ziegele, and Oliver Quiring. “Sleeper effect from below: Long-term effects of source credibility and user comments on the persuasiveness of news articles.” New media & society 20, no. 12 (2018): 4765-4786. [CrossRef]

- Nadarevic, Lena, Rolf Reber, Anne Josephine Helmecke, and Dilara Köse. “Perceived truth of statements and simulated social media postings: an experimental investigation of source credibility, repeated exposure, and presentation format.” Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 5, no. 1 (2020): 1-16.

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. “Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking.” Journal of personality 88, no. 2 (2020): 185-200.

- Sindermann, Cornelia, Andrew Cooper, and Christian Montag. “A short review on susceptibility to falling for fake political news.” Current Opinion in Psychology 36 (2020): 44-48. [CrossRef]

- Escolà-Gascón, Álex, Neil Dagnall, Andrew Denovan, Kenneth Drinkwater, and Miriam Diez-Bosch. “Who falls for fake news? Psychological and clinical profiling evidence of fake news consumers.” Personality and Individual Differences 200 (2023): 111893. [CrossRef]

- Bowes, Shauna M., and Arber Tasimi. “Clarifying the relations between intellectual humility and pseudoscience beliefs, conspiratorial ideation, and susceptibility to fake news.” Journal of Research in Personality 98 (2022): 104220.

- Bago, Bence, David G. Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. “Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines.” Journal of experimental psychology: general 149, no. 8 (2020): 1608. [CrossRef]

- Plieger, Thomas, Sarah Al-Haj Mustafa, Sebastian Schwandt, Jana Heer, Alina Weichert, and Martin Reuter. “Evaluations of the Authenticity of News Media Articles and Variables of Xenophobia in a German Sample: Measuring Out-Group Stereotypes Indirectly.” Social Sciences 12, no. 3 (2023): 168. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Fabian, and Matthias Kohring. “Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: A panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German parliamentary election.” Political Communication 37, no. 2 (2020): 215-237. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S. Mo, Tara Mortensen, and Jingjing Liu. “Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t.” American behavioral scientist 65, no. 2 (2021): 371-388.

- Craft, Stephanie, Seth Ashley, and Adam Maksl. “News media literacy and conspiracy theory endorsement.” Communication and the Public 2, no. 4 (2017): 388-401. [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, Paul, and Samantha Viotty. “Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: Civic expression, fake news, and the role of media literacies in “post-fact” society.” American behavioral scientist 61, no. 4 (2017): 441-454.

- Rosen, Jan B., Matthias Brand, and Elke Kalbe. “Empathy mediates the effects of age and sex on altruistic moral decision making.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 10 (2016): 67. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sian, Joshua P. Forrest, Jessica Strait, Haeseung Seo, Dongwon Lee, and Aiping Xiong. “Beyond cognitive ability: Susceptibility to fake news is also explained by associative inference.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-8. 2020.

- Lutzke, Lauren, Caitlin Drummond, Paul Slovic, and Joseph Árvai. “Priming critical thinking: Simple interventions limit the influence of fake news about climate change on Facebook.” Global environmental change 58 (2019): 101964. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Katherine, Spencer Blair, Jonathan A. Busam, Samuel Forstner, John Glance, Guy Green, Anna Kawata et al. “Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media.” Political behavior 42 (2020): 1073-1095. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ping, Juncai Sun, Wenhai Zhang, and Dan Li. “Effect of empathy trait on attention to positive emotional stimuli: evidence from eye movements.” Current Psychology (2020): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- De Waal, Frans BM, and Stephanie D. Preston. “Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 18, no. 8 (2017): 498-509.

- Eres, Robert, Jean Decety, Winnifred R. Louis, and Pascal Molenberghs. “Individual differences in local gray matter density are associated with differences in affective and cognitive empathy.” NeuroImage 117 (2015): 305-310. [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, Simone G. “The neural bases for empathy.” The Neuroscientist 17, no. 1 (2011): 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Hikaru, Yasuyuki Taki, Rui Nouchi, Atsushi Sekiguchi, Hiroshi Hashizume, Yuko Sassa, Yuka Kotozaki et al. “Association between resting-state functional connectivity and empathizing/systemizing.” Neuroimage 99 (2014): 312-322. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, Boris C., Olga M. Klimecki, Susanne Leiberg, and Tania Singer. “Structural covariance networks of the dorsal anterior insula predict females’ individual differences in empathic responding.” Cerebral Cortex 24, no. 8 (2014): 2189-2198. [CrossRef]

- Meneses, Rita W., and Michael Larkin. “The experience of empathy: Intuitive, sympathetic, and intellectual aspects of social understanding.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 57, no. 1 (2017): 3-32.

- Yu, Chi-Lin, and Tai-Li Chou. “A dual route model of empathy: A neurobiological prospective.” Frontiers in psychology 9 (2018): 2212. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, Bilal, Paolo Rosso, and Francisco Rangel. “An emotional analysis of false information in social media and news articles.” ACM Transactions on Internet Technology (TOIT) 20, no. 2 (2020): 1-18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).