1. Introduction

Rehospitalization of newborns within the first month after initial release is a frequent occurrence that causes disturbances for patients and their families, as well as financial strain on healthcare systems. Research on neonatal readmission in the past has concentrated on maternal and neonatal factors [

1].

Potentially preventable problems including jaundice and feeding problems account for the majority of hospital readmissions among newborns within 28 days after discharge [

2].

In addition to being linked to high rates of morbidity and mortality, the neonatal period is the most crucial time in life for laying a solid foundation for overall health. Because rates of neonatal readmissions can reach 10.1% outside of the US, this is a global concern. Neonatal readmissions do incur significant costs for patients, their families, and the healthcare system as a whole. A number of tests and examinations are conducted to determine whether the newborn is ready for discharge from maternity units. Nevertheless, some neonates may experience readmission at any age. For this reason, determining the related maternal and neonatal risk factors is crucial when analyzing how age affects neonatal outcomes, care-givers, and financial obligations [

3].

Generally, in Ploiești Maternity Hospital, newborns are discharged by 72 hours of life if born via C-section or 48 hours of life if born vaginally. If the mother-neonate dyad fit the criteria for discharge, it can be done earlier than 72 hours (the newborn is breastfeeding, bloodwork and clinical state are normal and the mother has been informed and trained for the care and resolution of any problems that may arise at home).

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a longitudinal retrospective observational study over a period of one year (November 2022- November 2023), that aimed to evaluate the prevalence of newborns admitted to a pediatric center in Ploiești, Romania, after being discharged from the maternity.

The main objectives included the identification and description of the most important diagnosis of hospitalized newborns in the pediatrics unit during the first 28 days of life (the neonatal period corresponds to 0-28 days). The inclusion criteria were: newborns with any signs of disease or poor condition, hospitalized in pediatrics, aged up to 28 days, based on clinical or paraclinical data. Patients with late-onset symptoms such as feeding difficulties, fatigue during meals, and growth failure were also included in this study, Exclusion criteria were: incomplete data, infants who were older than 28 days. Data was collected from the hospital's electronic register using Microsoft Excel software and simple random sampling to reduce bias. The IBM SPSS version 26 software was used for data analysis and graphical representation. Normal weight at term refers to weight from 2800g to 3999g at gestational age between 37-42 weeks and prematurity refers to a gestational age below 37 weeks, with subcategories of late preterm (32-37 weeks of gestation), very preterm (28-32 weeks), and extremely preterm (<28 weeks).

A backward regression model was used to estimate relationships between a dependent variable (age at admission) and more independent variables (gender, APGAR score, type of birth, term or preterm neonate, maternal age, number of children, rural/urban residence, age at maternity discharge, and breastfeeding/bottle feeding). This analysis involves starting with all potential predictors and systematically removing those that contribute the least to the model's predictive power. This approach ensures a more efficient and accurate model by retaining only the most significant variables

3. Results

Our study included 108 newborns admitted to the Pediatric Hospital in the city of Ploiești, which were discharged with good general condition from the maternity ward, but who presented to the pediatric ward in the immediately following period, up to 28 days of life, with various symptoms, specific to the newborn, but also to the young child.

A quarter of the newborns included in the study (25%) were diagnosed with mild protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) being exclusively breastfed or both formula and mother’s own milk. Twenty-two cases (20.3%) had fever as the main sign of either infectious cause or dehydration. Nineteen infants (17,5%) had signs and symptoms on clinical examination suggestive of bronchiolitis such as cyanosis, oxygen saturations below 95% (SaO2<95%), respiratory distress, wheezing. Due to immaturity and fetal distress, premature babies, and those with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) were included in the study because there are vulnerable categories for hospitalization in pediatrics units during the first period of life.

Table 1 describes the main diagnosis of the included patients and the percentage of each category.

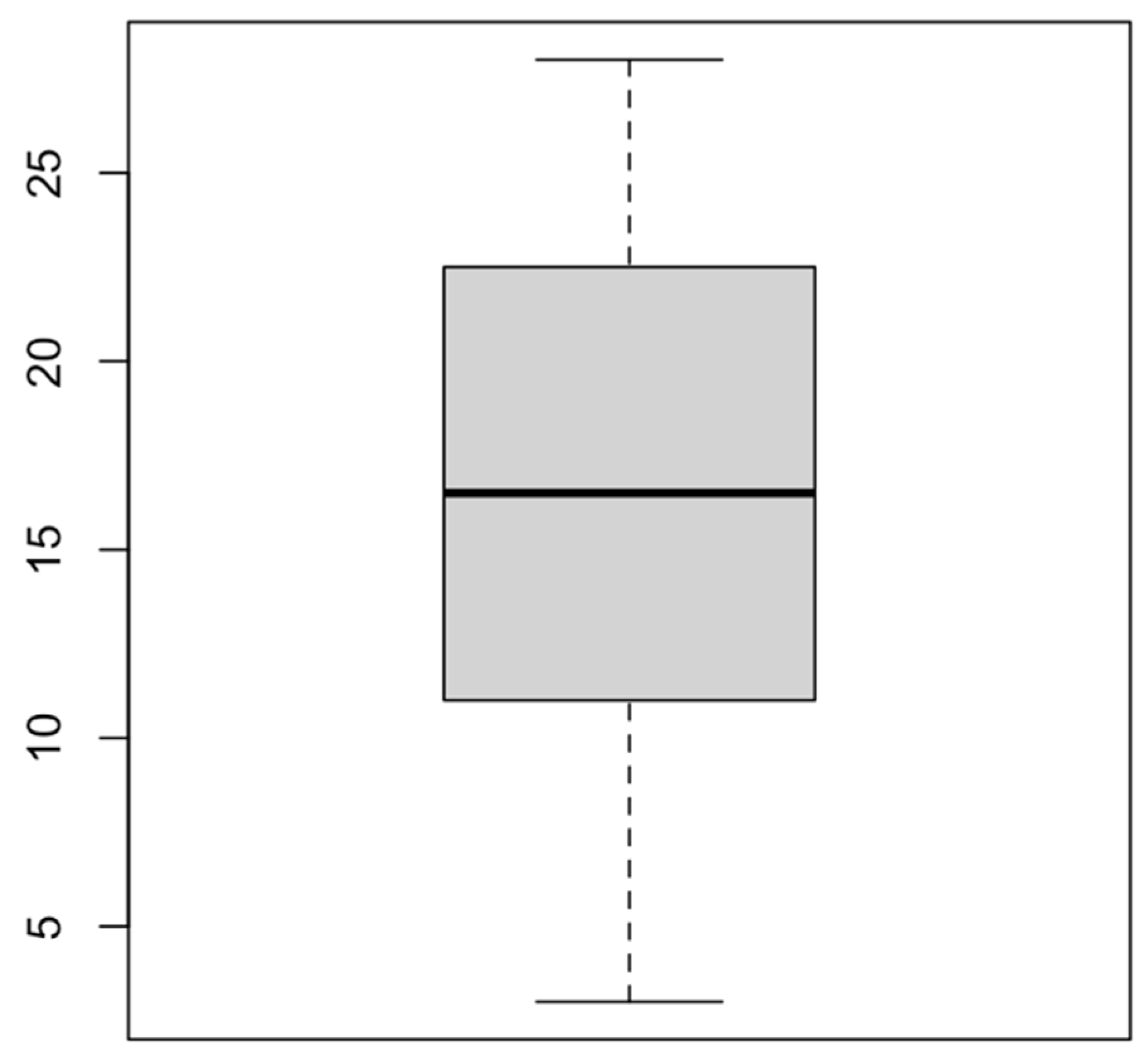

In this paper, the rate of readmission in the Pediatric Unit over a period of 1 year (2022-2023) was 5% (108 readmissions), related to 2140 births which took place for the corresponding year in Ploiești. The readmission age (quantified in days) was observed to be between 3 and 28 days of life, with a mean of 16.57 days and a mode of 13 days.

Figure 1 describes the data spread according to the age of readmission for our studied group.

The key aspects of our study were to identify a correlation between different group characteristics and the readmission age. A number of aspects were evaluated, starting from birth parameters, such as gender, Apgar score, type of birth, gestational age, maternal age, number of children, and ending with feeding type (breast or bottle feeds), area of residence, and age in days at discharge from the maternity ward, and are detailed in

Table 2.

Most of our observed group were male (65 vs 43), with a dominance of an Apgar score between 8 and 10 (88.8%) and a slight difference between cesarean section and vaginal birth (60 vs 48). The peak age represented in the maternal group was 18-35 years (88.8%), followed by 15 mothers aged >35 (13.8%) and 12 aged <18 years (11.1%). Almost all readmitted newborns were first born (77.7%) and from an urban area of living (70.3%). During maternity stay, nearly all cases were discharged within 2 or 3 days of life (34.2% and 55.5%, respectively), showing no signs of early postnatal complications.

What stands out is the fact that there was a strong correlation between the age of discharge from the maternity ward and the age of readmission (p<0.001), indicating a pattern of early readmission in the pediatric unit for patients who were released early from the maternity (between 48 and 72 hours of life). At the same time, the number of children (firstborn versus second, third and fifth born children) seemed to play an important role in readmission (p<0.001). On the other hand, some variables mentioned in

Table 3 did not have such an impact, the least correlation was shown by Apgar score (p=0.95), followed by gestational age. Surprisingly, the types of neonatal feeding, such as breastfeeding, mixed feeding (breastmilk and formula), and formula feeding alone were not of great impact on our lot (p=0.68).

On admission in the pediatric unit, based on symptoms, certain paraclinical investigations were performed, namely complete blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), peripheral and central cultures, antigens (influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2, rotavirus), and bilirubin levels. As observed in

Table 4, bacterial, as well as viral infections were present. Almost a quarter of cases were diagnosed with anemia (15.7%) and 12.9% with hyperbilirubinemia.

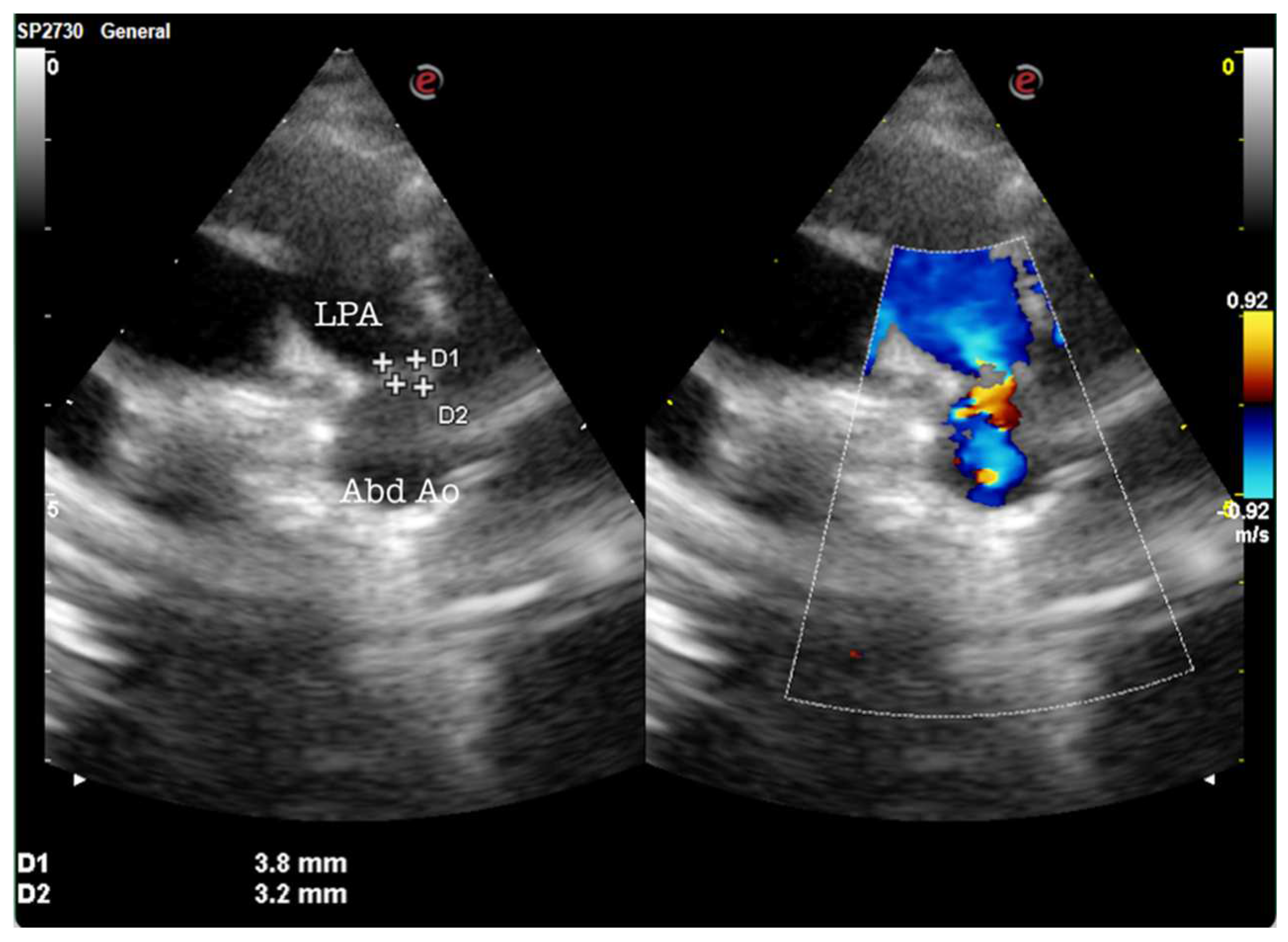

During the admission and care of these newborns, a multidisciplinary team performed ultrasonographic examinations all of the readmitted newborns, especially preterms and IUGR newborns. Of those evaluations, 12 underwent abdominal ultrasound, 19 required cerebral ultrasonography, and 15 required heart ultrasounds. What was interesting was the fact that two of them were diagnosed in the pediatric unit with patent ductus arteriosus, as observed in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

During the one-year study period (2022-2023), 5226 infants were admitted to our clinic. Out of them 2,1% (108 patients) were neonates that required hospitalization in pediatrics after being discharged home from the maternity hospital. The resulting prevalence for newborns was 5%, with 2140 birth during the studied period. This percentage of newborn babies admitted in a pediatric facility is consistent with worldwide studies reporting newborns as representing between 1 and 2,5% of the total pediatric consultations in the emergency department [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The moment of neonatal discharge (between 48 and 72 hours of life) from the maternity ward was the strongest indicator of early readmission in our study (p<0.001).

Previous research showed that males are more likely to be readmitted compared to females [

9]. Our findings are consistent with this affirmation since there is a predominance of male newborns at readmissions (60.1%) and fewer females (39.8%). On the other hand, our observations concluded gender does not have such a strong correlation to the age at readmission (p=0.169).

First time mothers are facing numerous challenges both during hospital stay, as well as after discharge. Our paper shows an important relationship between firstborns and the age at readmission (p<0.001). The study led by Feenstra M. et al. emphasizes the importance of maternal feelings of security and confidence in their maternal role, as they are closely connected to the process of becoming a mother [

10]. High risk pregnancies increase the likelihood of complications and readmission for newborns [

11,

12,

13].

In the present study, although the most prevalent diagnosis was infection, of bacterial or viral origin (bronchiolitis, enterocolitis, sepsis), the primary cause of readmission was represented by growth failure (25%). In a study conducted by Bawazeer M. et al. the most common cause of readmission was respiratory disease, followed by jaundice, and fever [

9]. Although only one patient was SARS-CoV-2 positive, fever was the most common COVID-19 patients admitted to a Pediatric Hospital in Bucharest [

14]. However, another study reported almost half of their readmissions being due to feeding problems (41%), followed by jaundice [

15,

16,

17].

Only 17,6% of the neonates were successfully breastfed at admission. Most of them were receiving mixed feeding, meaning both formula and breast milk (34,2%) while 33,3% were breastfed but mothers described encountering difficulties. A Romanian study published in 2018 related to feeding practices among Romanian children during the first year of life, reported that less than half of the included children were exclusively breastfed for four to six months [

18]. Similarly, our lot presented with a very low rate of breastfeeding compared with the ones reported in other countries. In Spain the breastfeeding rate goes as high as 81,7% while in Germany it reaches 82% and in Italy 91.1% [

19,

20,

21]. Our own clinical practice leads us to believe strong myths concerning breast milk persist among Romania’s population. Mothers who breastfeed are often discouraged by their female family members, usually by being told their milk “is not good enough”, or it “does not look fat enough”. Other factors that can contribute to the low rate of breastfed infants could be the short maternal hospital stay after birth (48 to 72 hours), combined with the high rate of cesarean sections in Romania. In the year 2017 the rate of C-sections in Romania was the second highest in Europe [

22]. Although breastfeeding is encouraged in all maternities, some mothers do not develop appropriate breastfeeding skills during the short hospital stay, and when they arrive home appropriate support lacks. Our country does not provide with a system for home-visits, although family physicians do sometimes offer home-visits for the newcomers. Lactation consultants are available in our country but only in the private sector and are quite expensive for some families.

Patients with late-onset symptoms such as feeding difficulties and fatigue during meals, along growth failure were included in this study, therefore a thorough evaluation of newborns who show stagnant growth and feeding difficulties was necessary to exclude cases of late diagnosed congenital heart disease (CHD), after maternity discharge, and to be able to have a differential diagnosis [

23].

The type of birth did not show a strong correlation with the age at readmission (p=0.65) in our paper, whilst cesarean birth (CB) has been associated with increased levels of postnatal depression and with a negative effect on breastfeeding, suggesting a possible link between maternal depression and neonatal readmission [

24].

Despite the fact that some hospitals or physicians recommend neonatal consults after discharge from the maternity ward, it is our strong belief there is a need for a national neonatal follow-up programme, which should be implemented in maternity hospitals, especially for high-risk infants.

5. Conclusions

Our study addressed the main causes and limitations of neonatal readmission and how they can be prevented. Malnutrition, feeding errors, and infections can be avoided by following the prevention rules of nosocomial infections, such as hand hygiene of mothers and medical staff, by informing and showing mothers the benefits of breastfeeding. Also, all newborns discharged from the maternity ward should benefit from follow-up at 7-10 days of life. The examination should be led by a neonatologist for both counselling and supervision of feeding.

Perhaps the most important step in the evolution of newborns admitted to the pediatrics unit would be a multidisciplinary team. In our study, newborns received the following consultations: neonatologist, pediatrician, cardiologist, pediatric surgeon, ultrasonography specialist, and pediatric neurologist. This has increased the quality of care, decreased the number of hospital days and reduced neonatal morbidity and mortality. Our results demonstrate the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary team and support promotion of breastfeeding, along with neonatal/pediatric surveillance programme as a national public health strategy. Screening for detection of congenital heart defects (CHD) is crucial in all newborns in the maternity ward using clinical evaluation. If any suspicion of CHD exists, the clinical assessment must be accompanied by paraclinical investigations. Delaying early diagnosis during the neonatal period can lead to an increase in morbidity and mortality associated with this pathology. Therefore, it is essential to implement CHD screening protocols in all maternity hospitals, regardless of their level.

Therefore, it is essential for all doctors, especially neonatologists, to stay up to date with the latest research, guidelines, and techniques related to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of any disease that can impact the newborn after discharge.

Finally, quality control measures should be implemented, and regular evaluation of the surveillance program should be conducted to assess its effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. We hope that our recommendations can serve as a roadmap for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and researchers working to address this critical public health issue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R. and A.T.C.; methodology, D.E.P.; software, A.M.C.J.; validation, I.R., A.T.C. and A.T.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, I.R.; resources, A.T.C.; data curation, A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.C.J.; writing—review and editing, I.R.; visualization, I.R. and A.T.C.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact it was a retrospective observational study.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact it was a retrospective observational study.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hensman, A.M.; Erickson-Owens, D.A.; Sullivan, M.C.; Quilliam, B.J. Determinants of Neonatal Readmission in Healthy Term Infants: Results from a Nested Case–Control Study. Am. J. Perinatol. 2021, 38, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Shori, N.; Bone, A.; Jawad, M. P645 An Audit to Improve Neonatal Readmission Number at Wexford General Hospital. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, A407–A408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, M.; Alsalamah, R.K.; Almazrooa, D.R.; Alanazi, S.K.; Alsaif, N.S.; Alsubayyil, R.S.; Althubaiti, A.; Mahmoud, A.F. Neonatal Hospital Readmissions: Rate and Associated Causes. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudet, I.; De Montis, P.; Debuisson, C.; Maréchal, C.; Honorat, R.; Grouteau, E. Fréquentation Des Urgences Pédiatriques Par Les Nouveau-Nés. Arch. Pediatr. 2012, 19, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Solís, D.; Pardo de la Vega, R.; Fernández González, N.; Ibáñez Fernández, A.; Prieto Espuñes, S.; Fanjul Fernández, J.L. [Neonatal visits to a pediatric emergency service]. An. Pediatr. Barc. Spain 2003 2003, 59, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, S.; Woolfenden, S.; Holdgate, A.; Lee, M.; Leung, M. Neonatal Presentations to a Mixed Emergency Department. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 43, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri Dávila, E.; Ferreira García, M.I.; Bello Pedrosa, O.; de Leonardis Capelo, D. [Neonatal hospitalization through a hospital emergency service in Uruguay]. An. Pediatr. Barc. Spain 2003 2005, 63, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Ruiz, C.; Trenchs Sainz de la Maza, V.; Curcoy Barcenilla, A.I.; Lasuen del Olmo, N.; Luaces Cubells, C. [Neonatal management in the emergency department of a tertiary children’s hospital]. An. Pediatr. Barc. Spain 2003 2006, 65, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, M.; Alsalamah, R.K.; Almazrooa, D.R.; Alanazi, S.K.; Alsaif, N.S.; Alsubayyil, R.S.; Althubaiti, A.; Mahmoud, A.F. Neonatal Hospital Readmissions: Rate and Associated Causes. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, M.M.; Nilsson, I.; Danbjørg, D.B. Broken Expectations of Early Motherhood: Mothers’ Experiences of Early Discharge after Birth and Readmission of Their Infants. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotogea, M.; Isam, A.J.; Frincu, F.; Zgura, A.; Bacinschi, X.; Sandru, F.; Duta, S.; Petca, R.C.; Edu, A. An Overview of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2022, 12, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, C.; Dobjanschi, C.; Isopescu, F.; Rusu, E.; Edu, A.; Radulian, G. Contribution of Maternal Obesity and Weight Gain in Pregnancy to the Occurrence of Gestational Diabetes. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2015, 67, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edu, A.; Teodorescu, C.; Dobjanschi, C.G.; Socol, Z.Z.; Teodorescu, V.; Matei, A.; Albu, D.F.; Radulian, G. Placenta Changes in Pregnancy with Gestational Diabetes. Romanian J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. Roum. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57, 507–512. [Google Scholar]

- Jugulete, G.; Pacurar, D.; Pavelescu, M.L.; Safta, M.; Gheorghe, E.; Borcoș, B.; Pavelescu, C.; Oros, M.; Merișescu, M. Clinical and Evolutionary Features of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (COVID-19) in Children, a Romanian Perspective. Child. Basel Switz. 2022, 9, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- http://viorel.tel BENEFITS OF OLIGOFRUCTOSE AND INULIN IN MANAGEMENT OF FUNCTIONAL DIARRHOEA IN CHILDREN – INTERVENTIONAL STUDY – Farmacia Journal Available online: https://farmaciajournal.com/issue-articles/benefits-of-oligofructose-and-inulin-in-management-of-functional-diarrhoea-in-children-interventional-study/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Young, P.C.; Korgenski, K.; Buchi, K.F. Early Readmission of Newborns in a Large Health Care System. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Păcurar, D.; Leşanu, G.; Dijmărescu, I.; Ţincu, I.F.; Gherghiceanu, M.; Orăşeanu, D. Genetic Disorder in Carbohydrates Metabolism: Hereditary Fructose Intolerance Associated with Celiac Disease. Romanian J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. Roum. Morphol. Embryol. 2017, 58, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Becheanu, C.A.; Ţincu, I.F.; Leşanu, G. Feeding Practices among Romanian Children in the First Year of Life. Hong Kong J. Paediatr. 2018, 23, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Río, I.; Luque, A.; Castelló-Pastor, A.; Sandín-Vázquez, M.D.V.; Larraz, R.; Barona, C.; Jané, M.; Bolúmar, F. Uneven Chances of Breastfeeding in Spain. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2012, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Lippe, E.; Brettschneider, A.-K.; Gutsche, J.; Poethko-Müller, C. [Factors influencing the prevalence and duration of breastfeeding in Germany: results of the KiGGS study: first follow up (KiGGS Wave 1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2014, 57, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, M.; Riva, E.; Banderali, G.; Scaglioni, S.; Veehof, S.H.E.; Sala, M.; Radaelli, G.; Agostoni, C. Feeding Practices of Infants through the First Year of Life in Italy. Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor. 1992 2004, 93, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simionescu, A.A.; Horobeţ, A.; Marin, E.; Belaşcu, L. Who Indicates Caesarean Section? A Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Level Maternity on Patients and Doctors’ Profiles at Childbirth. Obstet. Şi Ginecol. 2021, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, A.; Cinteză, E. Esențialul În Cardiologia Pediatrica; Amaltea, 2022; ISBN 9789731622255.

- De Mare, K.E.; Bourne, D.; Rischitelli, B.; Fan, W.Q. Early Readmission of Exclusively Breastmilk-Fed Infants Born by Means of Normal Birth or Cesarean Is Multifactorial and Associated with Perinatal Maternal Mental Health Concerns. Birth n/a. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).