1. Introduction

Poroid neoplasms (PN) are a group of heterogeneous tumors with sweat glands and folliculo-sebaceous differentiation representing 10% of primary sweat gland tumors [

1,

2,

3]. Since the first description by Pinkus et al. in 1956 [

4], it is now well established that this group of neoplasms include 4 main benign entities according to their architecture, location in the dermis and connexion with the epidermis: classic poroma (CP), formally known as eccrine poroma, that is located in the dermis with broad epidermal connexion, hidroacanthoma simplex (HS) restricted to the epidermis, dermal duct tumor (DDT) that is intradermal with numerous small lobules, and poroid hidradenoma (PH) which is also intradermal but with larger cystic nodules [

3,

5]. All these neoplasms show a mixture of small, round, basophilic poroid cells and larger eosinophilic squamoid cuticular cells, often associated with ductal structures that have eccrine or apocrine differentiation [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Also, these 4 benign lesions could coexist in a same lesion [

1,

7]. It is now well established by many studies that PN derive from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and the lower acrosyringium [

3,

8]. Malignant transformation of PN into porocarcinoma has been reported in the literature [

9,

10]. Rarely PN can present with sebaceous [

11,

12] or follicular differentiation [

13] along with clear cell changes, keratinization [

1] or melanin pigments [

14,

15]. In earlier studies, PN have been reported with classical palmoplantar locations in elderly patients [

4,

6], however subsequent studies challenged these reports, with non-palmoplantar locations and occurrence in younger patients [

3,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Also, apocrine differentiation has been reported in later reports and is not so unusual as believed [

7,

19,

20,

21].

We reported herein, to the best of our knowledge the first series about clinical and histopathological features of PN in our subsaharan African country.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study on PN registered at our newly operative Pathology laboratory from February 2020 to February 2024 (4 years). Clinical data were retrieved from the pathology request forms as well as from phone calls of patients’ surgeons.

The histological diagnosis has been made on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded surgically resected specimens, and stained by hematoxylin-eosin (HE).

Additional serial sections were performed on all retrieved archival paraffin-embedded specimens and re-assessed by two pathologists (BE and IB) in search for some eventually initially missed histological features: epidermal connexion, folliculo-sebaceous differentiation, clear cell changes, horn cysts, squamous eddies, necrosis en masse, eccrine or apocrine ductal differentiation.

A part of this study has been presented as an E – poster at the 61st International Academy of Pathology (IAP), Thailand division, Annual meeting 2022, 2nd – 4th November 2022, virtual meeting.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical features

The

Table 1 summarizes the clinical features of our series of PN.

The mean age was 41.1 years (range of 12 – 70 years) with a slight female predominance (sex ratio = 1.16). The most frequent tumor’s locations were the scalp (3 cases, 23.1%) (

Figure 1a), the sole (3 cases, 23.1%) (

Figure 1 b), and the thoracic wall (2 cases, 15.4%). Only 4/13 cases (30.8%) had classical palmoplantar locations as the majority of patients had tumors located in hair-bearing parts of the body. The mean tumor size was 3.7 cm (range of 0.4 – 8 cm). All lesions were grossly well-circumscribed, with ulcerations in 4 cases (30.8%). PN appeared grossly as solid (7/13 cases,53.8%) or solid-cystic lesions (6/13 cases, 46.2%) with whitish or pink color and mucinous content (

Figure 1 c). The preoperative clinical diagnosis was suggestive of malignancy in 9/13 cases (69.2%).

All patients had complete surgical resections of their tumors, and none had reported recurrence at the time of this report.

3.2. Histopathological features

Histopathological features of our patients were summarized in

Table 2.

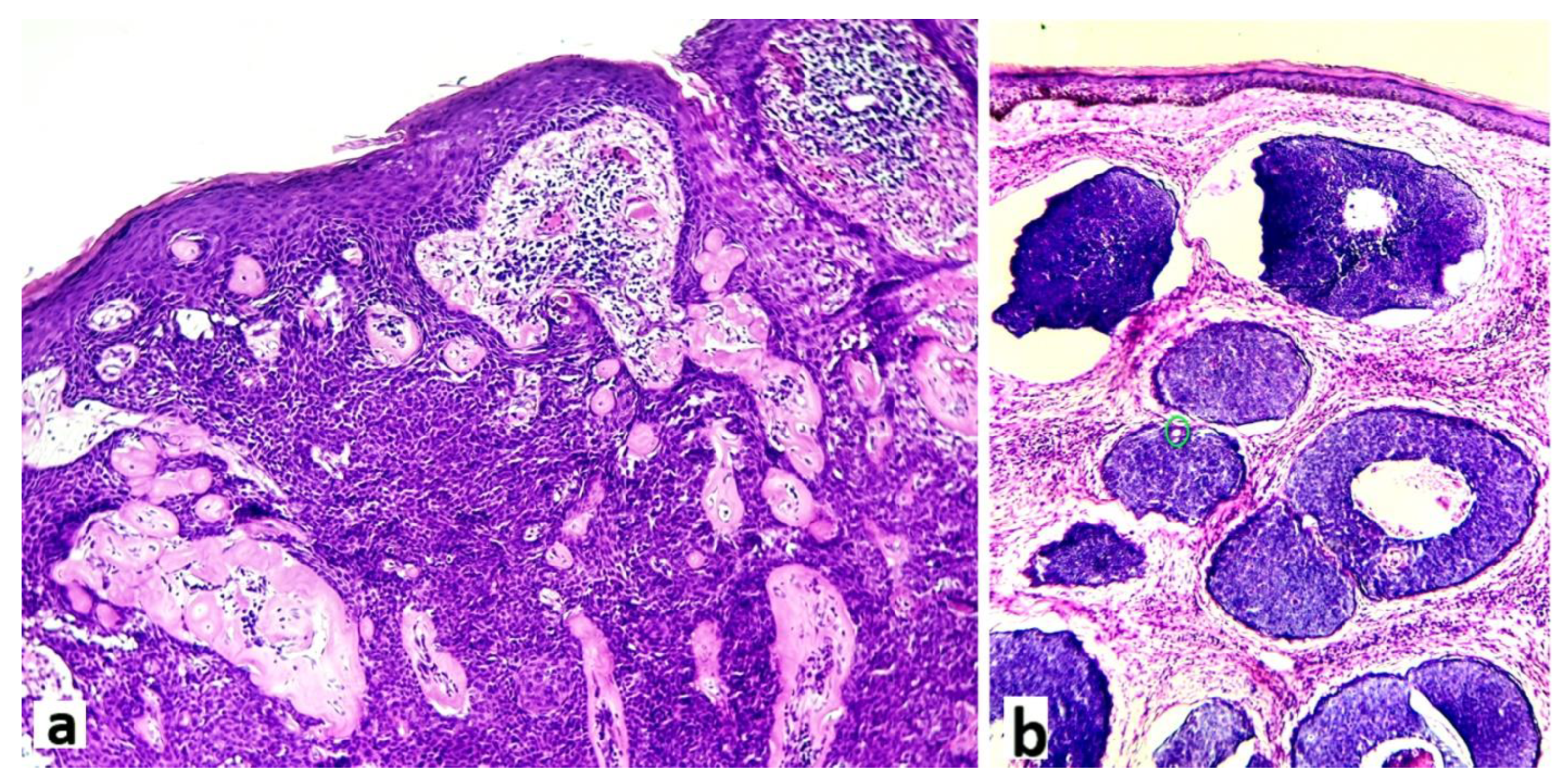

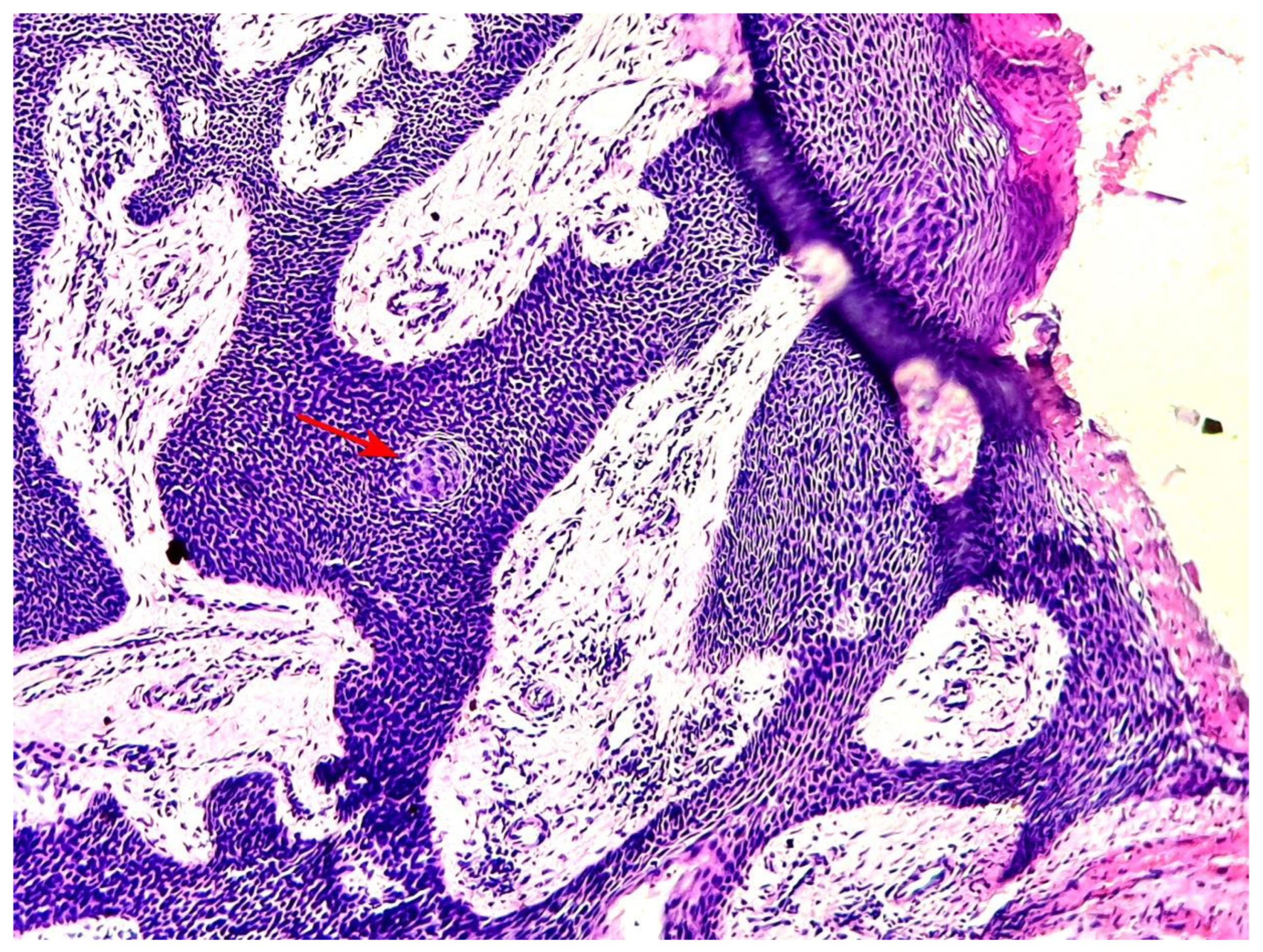

After serial additional sections, the final diagnoses of the 13 patients were: 10 classic poromas (CP) (76.9%) (

Figure 2 a), 2 poroid hidradenomas (PH) (15.4%) and 1 dermal duct tumor (DDT) (7.7%) (

Figure 2 b).

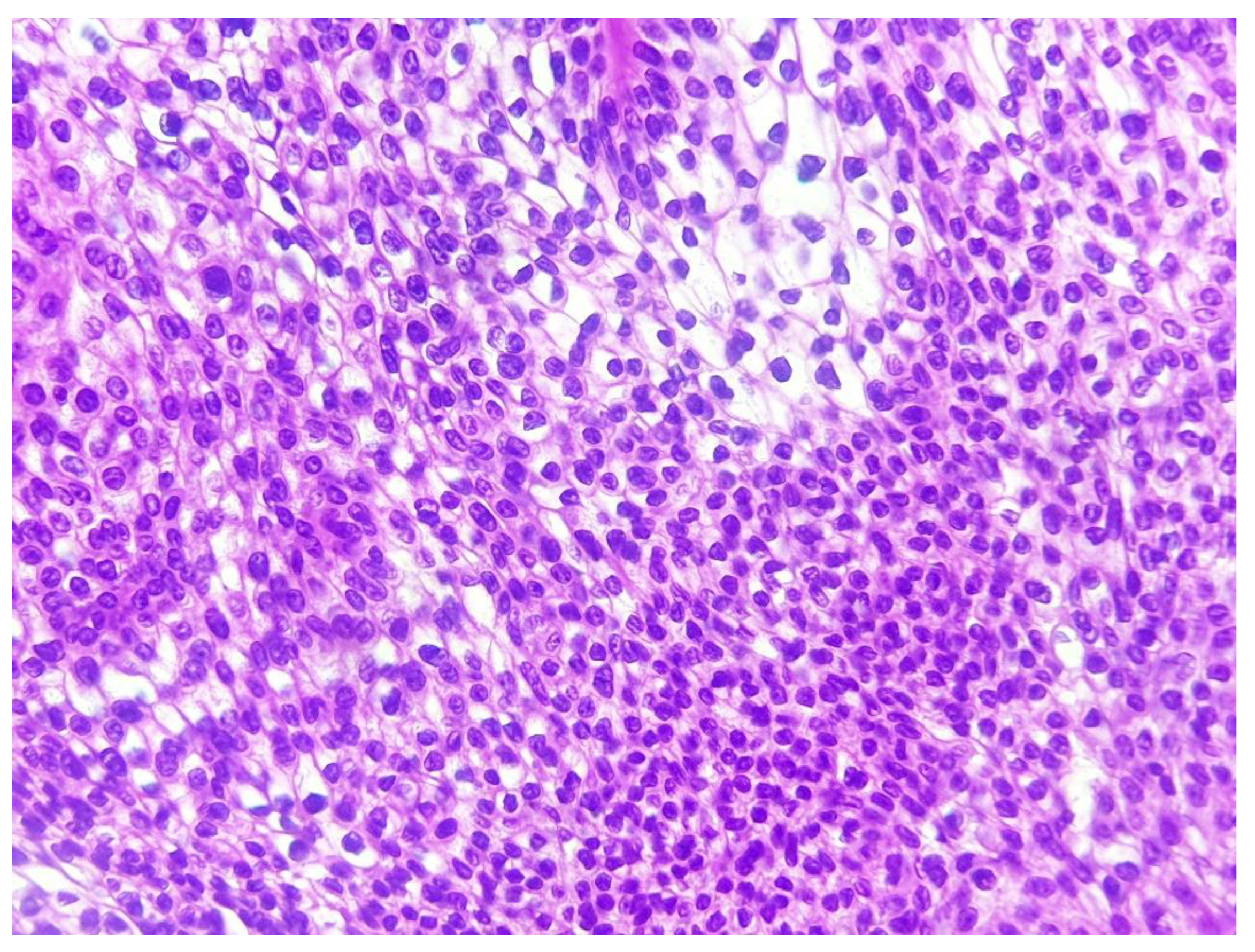

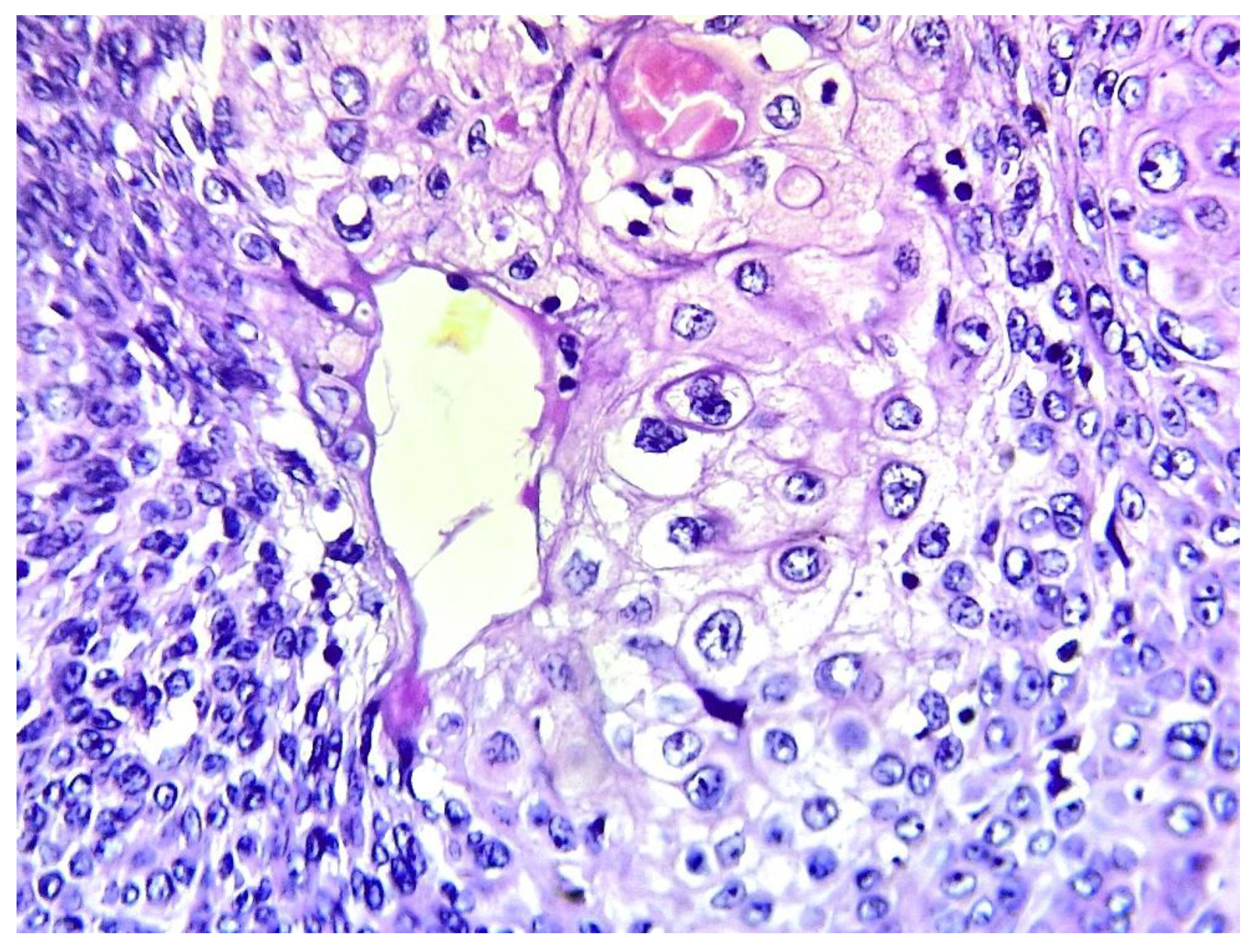

All cases were made of a variable mixture of poroid (uniform small cuboidal cells with round nuclei) and cuticular cells (larger cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm), without cellular atypias, mitoses or stromal infiltration. The tumors’ stroma was fibro-hyaline and inflammatory in all cases, sometimes loose and myxoid. A broad epidermal connexion was observed in all cases of CP, whereas absent in cases of PH (cases 6 and 9) and DDT (case 12). Clear cells were observed in 7 cases (53.8%) (

Figure 3).

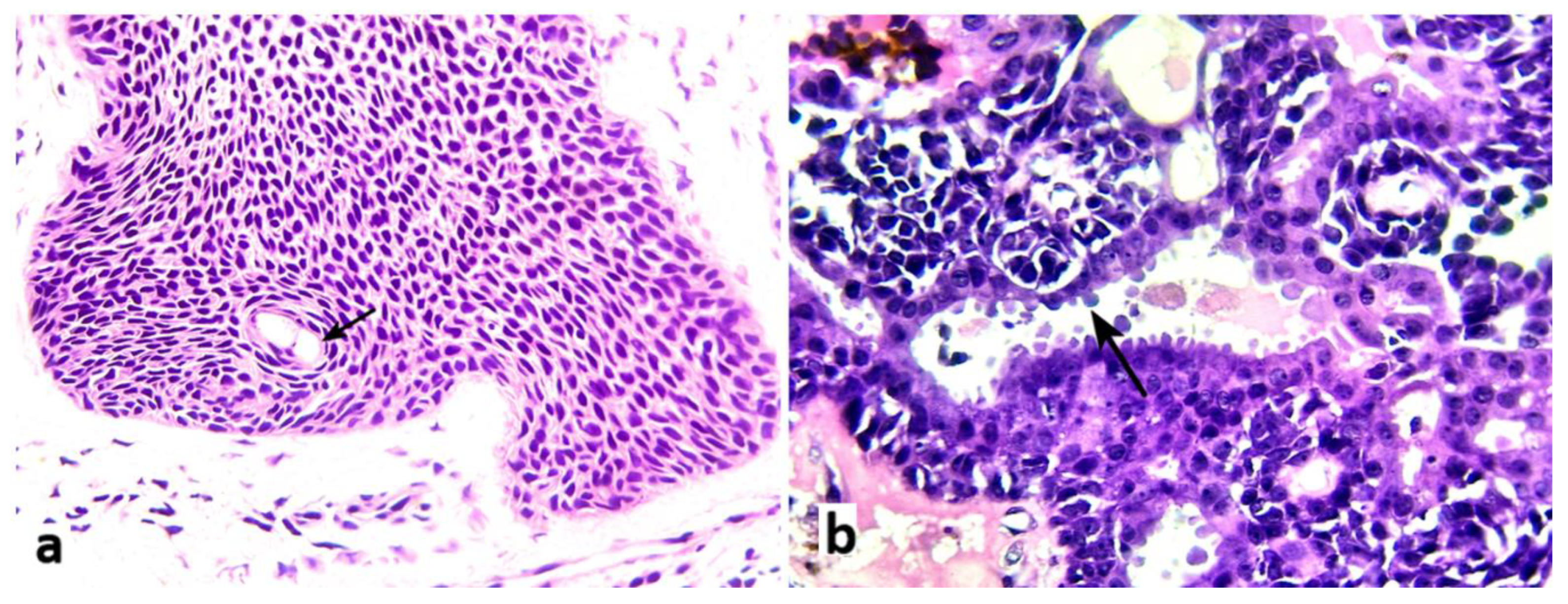

Ductal structures were generally dilated and cystic with eosinophilic amorphous contents, with pure eccrine differentiation in 7/13 cases (53.8%) (

Figure 4 a, arrow), mixed eccrine/apocrine differentiation in 5/13 patients (38.5%) and 1 pure apocrine differentiation (bulging apical cytoplasm with decapitation secretions) (

Figure 4 b, arrow).

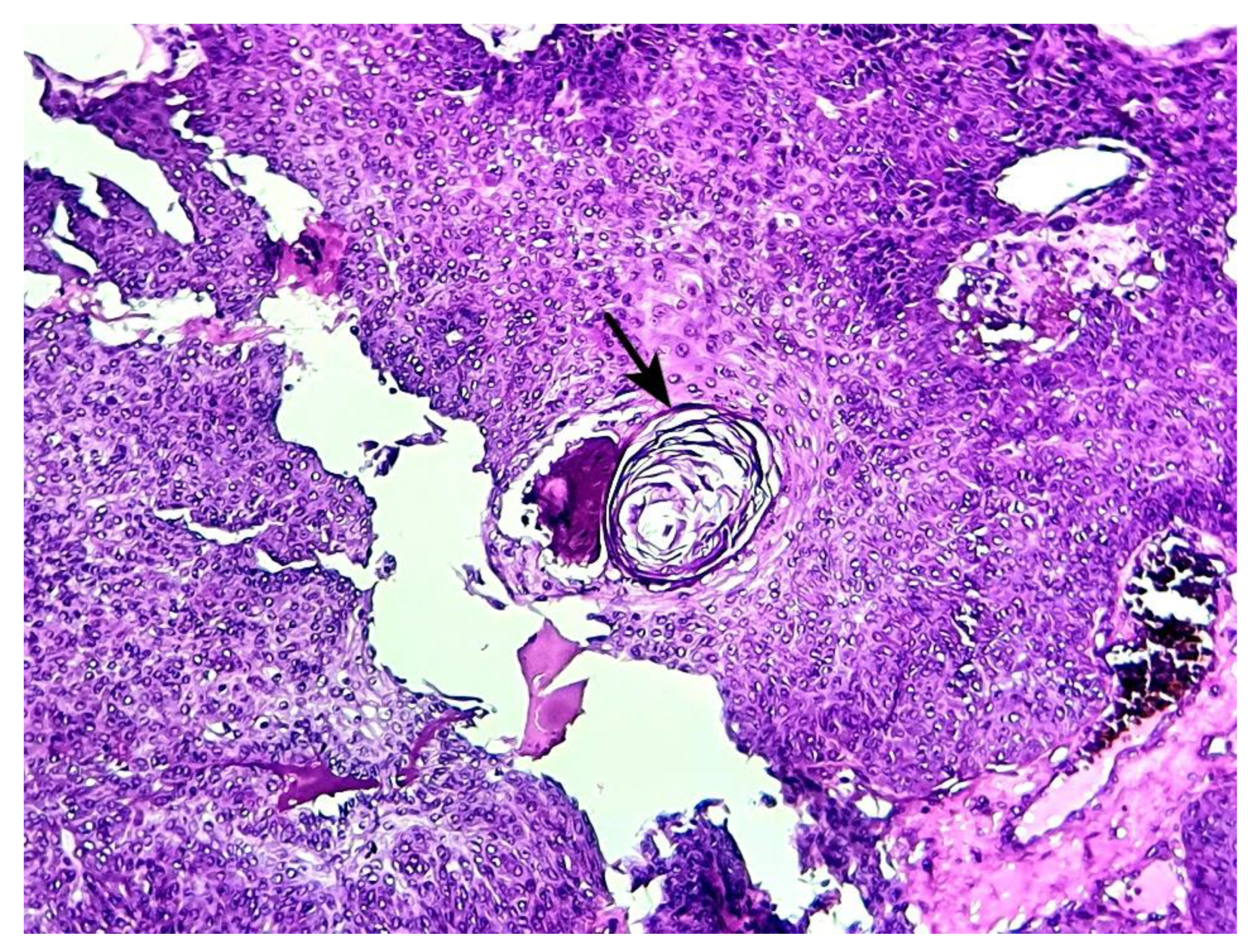

Focal keratin horns were present in 2 patients (15.4%) (

Figure 5, arrow), while focal poroid cells maturation as squamous eddies were found in 6 cases (46.2%) (

Figure 6, arrow).

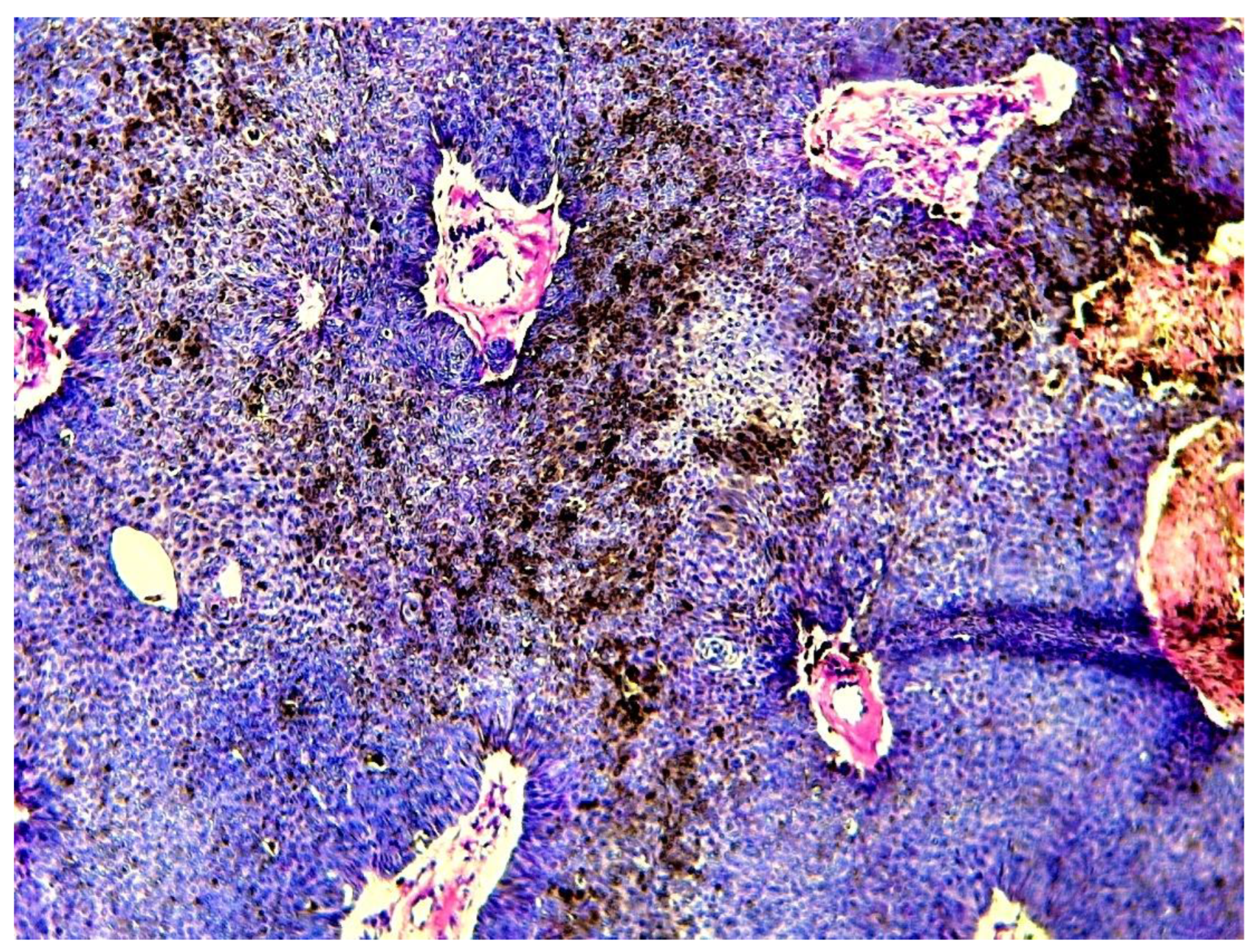

Sebaceous differentiation (

Figure 7) and melanin pigments (

Figure 8) were present respectively in 2 and 1 patients. Despite serial additional cuts, follicular or necrosis en masse, have not been found in all the 13 cases of the current series.

4. Discussion

Over a period of 4 years since the creation of the first operative Pathology laboratory in a public hospital in our country, we have registered 13 cases of poroid neoplasms (PN). The duration of our study is too short to reflect the real epidemiological characteristics of these neoplasms in our context, however some conclusions could be drawn from our current small series.

Poroid neoplasms are rarely reported tumors across the literature, with case reports [

11,

15,

17,

22,

23,

24,

25], small series and few large series with limited sample (no more than 400 cases) [

1,

3,

9,

26,

27]. From 1988 to 2003 Chen et al. have registered 25 cases in Taiwan [

1], while Beti et al. in Italy [

16], Batistella et al. in France [

3], have respectively reported 101 cases from 1994 to 2012, and 266 cases from 1980 to 2008. To the best of our knowledge, Ito et al. have reported the largest series of PN with 384 cases [

7].

In our series, the mean age was 41.1 years (range of 12 – 70 years) with a slight female predominance (sex ratio = 1.16). Our patients were younger than what is commonly reported in the literature where the mean age turns around 50 – 60 years, with no established sex predominance in larger series [

1,

3,

7,

28]. However, cases of PN in children and younger patients were reported [

23,

29,

30].

Earlier reports found that PN were classically located in palm and sole [

4,

28], however additional studies proved the opposite by reporting more frequent locations in hair-bearing areas of the body such as the head and neck regions, the trunk and limbs [

1,

7,

16]. Our results are in accordance with these later studies as 9/13 (69.2%) of our patients had tumors located in hair-bearing sites of the body.

Poroid neoplasms are usually solitary lesions but multiple locations (eccrine poromatosis) have been reported [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Eccrine poromatosis was usually reported in patients with a history of immunosuppression from radiation, chemotherapy or transplantation [

32,

33]. All of our patients had single tumors, and none was immunosuppressed. Tumors were well-circumscribed with ulcerations in 4 cases (30.8%), with a mean size of 3.7 cm (range of 0.4 – 8 cm). In our series, PN appeared as solid or solid-cystic lesions with whitish or pink color and mucinous content. Often, PN are red, pinkish or skin-colored elevated lesions on clinical examinations [

6] with solid or solid-cystic cut surface. The gross features reported in our series correspond mainly to resected specimens (ex vivo) after formalin fixation, thus quite different from clinical aspects (in vivo) of the tumors. Ulcerations were present in 4 of our cases, a fact that is not unusual according to previous studies [

3,

27].

The majority of cases were clinically suspected of malignancy in our series (9/13 cases), especially in patients with ulcerated or larger lesions. The clinical features of PN lack any specificity even on dermoscopic analysis [

26,

27]. In larger reported series, the clinical diagnosis of PN was more often missed, with numerous differential diagnoses such as pyogenic granuloma, nevus, hemangioma, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma,…etc [

1,

3,

6].

The definitive diagnosis of PN relies on the histopathological analysis. Poroid neoplasms have well-described characteristic morphological features, thus ancillary testing such as immunohistochemistry are not required for the diagnosis in routine histopathological practice [

3,

6,

26]. As in the majority of previous studies, our current cases have been diagnosed with the routine standard histopathology techniques (formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, and HE-staining).

Our histological diagnoses of PN consisted of 10 CP (76.9%), 2 PH (15.4%) and 1 DDT (7.7%), with apocrine ductal differentiation in 6 cases (46.2%). This frequent apocrine differentiation is in contradiction of what is commonly reported in the literature [

7,

19,

20]. The seemingly rare apocrine differentiation in previous studies would be likely due to the fact that apocrine ductal differentiation was overlooked on morphological evaluation and classification of PN [

7,

20,

35]. In fact apocrine differentiation seems to be relatively common in PN as Ito et al. have reported that a quarter of them show apocrine differentiation [

7]. In our series, sebaceous differentiation were observed in 2 cases (15.4%). In fact, sebaceous differentiation was found in 1.3 to 4.8% cases of PN in some reports [

7,

11].

Poroid neoplasms are characterized by an admixture of poroid and cuticular cells in variable proportion as reported in our series, however cases of PN with only poroid cells have been reported [

1]. Usually the proportion of poroid cells is predominant in PN, however in 2017 Alegria-Landa et al. have reported 2 cases of poromas mostly composed of cuticular cells and named them cuticular poromas [

36]. We found clear cells in 7/13 cases (53.8%), intermingled with other tumor cells, sometimes forming large clusters, a finding that is not uncommon in PN [

1]. Also, in 6/13 cases (46.2%), we have found focal maturation of poroid cells termed as squamous eddies. This feature was rarely reported in the literature [

1], likely because of its lack of diagnostic value. However we have observed focally keratin cysts (horn cyst) in 2 cases of our patients, a feature that could suggest the diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis especially in small biopsies when the lesion is connected to the epidermis and ductal structures not observed in the sample [

1].

Cases of recurrences (if incomplete resection) [

6,

25] or malignant transformation [

10,

37] of PN have been reported previously. Until now, we have not registered recurrence or malignant transformation in all of our patients. The surgical resection was complete in all cases, and there were no history of trauma or immunosuppression. Trauma and immunosupression have been reported as predisposing factors in patients with PN [

6,

31,

34].

5. Conclusions

Poroid neoplasms are rare benign adnexal tumors derived from sweat glands and folliculo-sebaceous units. Occurrence in younger patients and location in hair-bearing body parts are frequent. The clinical features are often misleading, with the definitive diagnosis relying on histopathological analysis of the resected specimens. Apocrine differentiation and clear cell changes are common in poroid neoplasms.

Author Contributions

BE wrote the article and made substantial contributions to its conception and design. ABAB, KAOK, IB, HHK, HSB, ISC, AS and HN were involved in drafting the manuscript and its critical revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. As the study was a retrospective report with de-identified, anonymous data, ethical approval and consent to participate were not required due to local/national guidelines (DAMTE/HNN, Ny-Nig/01/24).

Informed Consent Statement

As the study was a retrospective report with de-identified, anonymous data, ethical approval and consent to participate were not required due to local/national guidelines (DAMTE/HNN, Ny-Nig/01/24).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen C-C, Chang Y-T, Liu H-N. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006, 45, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA. Dermal Duct Tumor: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022, 9, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010, 32, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956, 74, 511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014, 53, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman AB, Brownstein MH. Eccrine poroma. An analysis of forty-five new cases. Dermatologica. 1969, 138, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito K, Ansai S-I, Fukumoto T. Clinicopathological analysis of 384 cases of poroid neoplasms including 98 cases of apocrine type cases. J Dermatol. 2017, 44, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langbein L, Cribier B, Schirmacher P. New concepts on the histogenesis of eccrine neoplasia from keratin expression in the normal eccrine gland, syringoma and poroma. Br J Dermatol. 2008, 159, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G; et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013, 227, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N; et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001, 25, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurashige Y, Yamamoto T, Okubo Y. Poroma with sebaceous differentiation: report of three cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2010, 51, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV; et al. Sebaceous differentiation in poroid neoplasms: report of 11 cases, including a case of metaplastic carcinoma associated with apocrine poroma (sarcomatoid apocrine porocarcinoma). Am J Dermatopathol. 2008, 30, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futagami A, Aoki M, Niimi Y. Apocrine poroma with follicular differentiation: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 2002, 147, 825–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu H-H, Lan C-CE, Wu C-S. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008, 35, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas ML, Díaz CJ, Rueda R. Pigmented Eccrine Poroma in abdominal region, a rare presentation. Colomb Med (Cali). 2013, 44, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betti R, Bombonato C, Cerri A. Unusual sites for poromas are not very unusual: a survey of 101 cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014, 39, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma M, Singh M, Gupta K. Eccrine poroma of the eyelid. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Majmudar V, Schollenberg E, Fish J. Pediatric Dermatology Photoquiz: An Ulcerated Nodule on the Abdomen of a Child. Eccrine poroma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016, 33, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azma A, Tawfik O, Casparian JM. Apocrine poroma of the breast. Breast J. 2001, 7, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya H, Oyama Z, Kitajima Y. “Apocrine” poroma: review of the literature and case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2001, 28, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka M, Kunisada M, Fujiwara N. Multiple apocrine poromas: a new case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2015, 42, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, SY. Case report of eccrine porocarcinoma in situ associated with eccrine poroma on the forehead. J Dermatol. 2012, 39, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi RR, Nepal A, Ghimire A. Eccrine poroma in neck of a child--a rare presentation. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009, 11, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim JS, Kwon ES, Myung KB. Poroid Hidradenoma: A Two-Case Report and Literature Review. Ann Dermatol. 2021, 33, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Quinn M, Gioe OA. Recurrent lesion on toe of young man. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Baraldi C. Dermoscopic-Histopathological Correlation of Eccrine Poroma: An Observational Study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019, 9, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari A, Buccini P, Silipo V; et al. Eccrine poroma: a clinical-dermoscopic study of seven cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009, 89, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983, 167, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang S-H, Tsai T-F. Congenital polypoid pigmented eccrine poroma of a young woman. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008, 22, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde K, Senger C, Ngan BY. Eccrine porocarcinoma in a child that evolved rapidly from an eccrine poroma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001, 37, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen K, Kim G, Chiu M. Eccrine poromatosis following chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019, 25, 13030–qt9177r4fp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014, 53, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo TT, Kole L, Elewski B. Eccrine Poromatosis: Case Report, Review of the Literature, and Treatment. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015, 1, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh RL, Kaffenberger B, Pootrakul L. Multiple Plantar Poromas in a Stem Cell Transplant Patient. Cureus. 2020, 12, e8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto O, Hisaoka M, Yasuda H. Cytokeratin expression of apocrine and eccrine poromas with special reference to its expression in cuticular cells. J Cutan Pathol. 2000, 27, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría-Landa V, Kutzner H, Requena L. Cuticular Poroma: A Poroma Mostly Composed of Cuticular Cells (Cuticuloma). Am J Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, e104–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juay L, Choi E, Huang J. Unusual Presentations of Eccrine Porocarcinomas. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022, 8, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).