1. Introduction

Childhood emotional abuse (CEA) is a distressing and detrimental type of maltreatment that can have significant and enduring impacts on an individual's overall health. It entails the ongoing mistreatment of a child's emotional needs, encompassing behaviors and verbal expressions that undermine their self-esteem, feelings of safety, and emotional growth (Thompson & Kaplan, 1996). The consequences of CEA and early interpersonal disruptive experiences go beyond the immediate circumstances and can have a lasting influence on an individual's psychological, emotional, and social well-being over their lifespan (Saladino et al., 2020; 2021; Verrastro et al., 2020). Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that CEA is linked to various negative outcomes, such as the development of maladaptive personality traits like neuroticism (Schwandt et al., 2012) and perfectionism (Miller & Vaillancourt, 2007), as well as the adoption of unhealthy coping strategies and behaviors, including workaholism (Sussman et al., 2011).

Neuroticism is distinguished by an inclination to encounter adverse emotions like anxiety, depression, and vulnerability. It exerts a notable influence on how an individual emotionally and behaviorally reacts to different occurrences in life (Barlow et al., 2014). Research has consistently discovered a robust correlation between CEA and elevated levels of neuroticism in adulthood (Wang et al., 2019). Individuals who have undergone emotional abuse during their developmental years are prone to displaying higher levels of neuroticism when compared to those who have not experienced such abuse. The pathways by which CEA contributes to heightened neuroticism are intricate and diverse. CEA can disrupt the formation of adaptive coping mechanisms, hinder the development of emotional regulation abilities, and distort an individual's self-perception and worldview (Thompson & Kaplan, 1996). These negative encounters can instill a pervasive feeling of insecurity, fear, and ongoing stress, ultimately giving rise to the display of neurotic characteristics (Schwandt et al., 2012). Furthermore, the influence of CEA on neuroticism extends beyond its direct effects. Emotional abuse can also shape the development of attachment styles and interpersonal connections, thereby amplifying neurotic inclinations (Wang et al., 2019). Individuals who have experienced emotional abuse during their childhood may encounter challenges related to trust, intimacy, and vulnerability, resulting in difficulties when it comes to forming and sustaining healthy relationships (Barberis et al., 2020; Thompson & Kaplan, 1996).

The connection between CEA and perfectionism has received growing recognition in psychological research. Perfectionism, which involves the establishment of lofty standards, self-criticism, and a relentless pursuit of flawlessness, is considered a prominent personality trait (Frost et al., 1990). Although a certain level of perfectionism can be beneficial, individuals who have undergone CEA may be more susceptible to the development of maladaptive forms of perfectionism, which can have a profound impact on their overall well-being. Studies have demonstrated a notable correlation between CEA and the emergence of perfectionistic characteristics (Miller & Vaillancourt, 2007). Individuals who have encountered emotional abuse in their early years may adopt perfectionistic inclinations as a means of coping. The relentless pursuit of perfection serves as a strategy to restore a sense of self-value and guard against potential emotional damage (Hill et al., 2011). Nonetheless, this dysfunctional manifestation of perfectionism can give rise to adverse outcomes, such as heightened stress, anxiety, and compromised overall well-being (Flett et al., 2014). CEA can contribute to the emergence of two distinct aspects of perfectionism: self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism (Smith et al., 2017). Self-oriented perfectionism encompasses the establishment of excessively high personal standards, engaging in self-criticism, and experiencing profound feelings of failure or disappointment when these standards are not met. On the other hand, socially prescribed perfectionism stems from the perception of external expectations for perfection, along with an excessive desire for external validation and approval.

The correlation between CEA and workaholism has garnered interest among researchers investigating the psychological factors influencing work-related behaviors and attitudes. Workaholism is defined as an overpowering and unmanageable compulsion to work, often at the cost of other aspects of life and personal well-being (Harpaz & Snir, 2003). Exploring the possible connection between CEA and workaholism provides insight into the intricate dynamics between early life experiences and work-related behaviors during adulthood. Studies indicate a noteworthy correlation between CEA and workaholism, emphasizing the relevance of examining this relationship (Sussman et al., 2011). Emotional abuse has the potential to influence an individual's self-perception, leading to a strong desire for external validation and approval. Workaholism can act as a compensatory mechanism to counter feelings of inadequacy by seeking control, accomplishment, and validation through work-related achievements (Andreassen et al., 2012). Moreover, workaholism can function as a means of diversion or avoidance from the emotional anguish and suffering linked to CEA, offering a momentary sense of purpose and achievement (Sussman et al., 2011). The connection between CEA and workaholism can be shaped by a range of factors, encompassing individual traits, coping strategies, and environmental influences (Andreassen et al., 2012). Individuals who have encountered emotional abuse during their childhood may develop a strong attachment to work, considering it a central aspect of their identity and a primary source of self-worth (Shapero et al., 2013). Additionally, workaholism can be perpetuated by societal and cultural expectations that prioritize productivity and accomplishment as indicators of success (Harpaz & Snir, 2003).

Considering the factors mentioned above, it is reasonable to argue that neuroticism plays a significant role in workaholism by intensifying the negative emotional effects associated with CEA. Individuals with high levels of neuroticism may be more prone to experiencing heightened levels of anxiety, stress, and dissatisfaction, which can drive their relentless pursuit of work-related goals as a means of managing or avoiding these adverse emotions. Moreover, CEA can cultivate a mindset of perfectionism, where individuals establish excessively high standards for themselves and engage in ceaseless work efforts to meet or surpass those standards. Consequently, this maladaptive perfectionism becomes intertwined with workaholism, as individuals persistently strive for success, recognition, and validation in their professional endeavors.

Another important topic discussed in the relevant literature is the potential presence of gender differences in workaholism. Aziz and Cunningham (2008) discovered that work stress and work-life imbalance are related to workaholism, regardless of gender. They also found that gender does not moderate the relationship between workaholism, work stress, and work-life imbalance. However, Burke and Berge Matthiesen (2009) found that women tend to have higher scores in terms of feeling driven to work, negative affect, exhaustion, and professional efficacy, while scoring similarly to men in terms of experiencing flow at work and absenteeism. Additionally, Burgess et al. (2006) found that men tend to score higher on work involvement and feeling driven to work, while women tend to score higher on job stress. Both genders showed similar scores on work outcomes.

CEA is a significant traumatic experience that can have long-lasting psychological effects. Investigating its link to workaholism provides valuable insights into how CEA impacts individuals' work-related attitudes and behaviors. Neuroticism and perfectionism are personality traits associated with both CEA and workaholism, and they may serve as mediators in the relationship between the two. This suggests that CEA can influence work-related behaviors through these traits. Understanding these connections has practical implications for interventions targeting workaholism. It emphasizes the importance of trauma-informed approaches that address the underlying psychological wounds and provide appropriate support. By recognizing the role of CEA and targeting neuroticism and perfectionism as mediators, interventions can effectively reduce the risk of workaholism and promote healthier work habits. Furthermore, by exploring the relationships among CEA, neuroticism, perfectionism, and workaholism, we can enhance existing theories and models in the field of workaholism and deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between childhood experiences, personality traits, and work-related outcomes. Lastly, despite previous research, there is still limited understanding of the presence and intricacies of gender differences concerning workaholism and other work-related factors. To fill this gap in knowledge, further investigation is necessary to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between gender, work-related behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes.

Therefore, the current study seeks to address these gaps in the existing literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess whether neuroticism and perfectionism mediate the relationship between CEA and workaholism (

Figure 1). Additionally, as an exploratory analysis, the study also examined whether the proposed model was invariant across different genders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved a sample of 1176 young workers from Italy, consisting of an equal number of females (588) and males (588), with ages ranging from 18 to 25 years old (mean age = 21.42, SD = 2.28). The participants were recruited through online platforms, primarily using social networks. In terms of educational background, 16% had completed middle school, 50% held a high school diploma, 31% had a university degree, and 3% had obtained a postgraduate degree. In relation to occupational status, 68% were employed, while 31% were self-employed. Regarding marital status, 41% of the participants were single, 44% were engaged, 12% were cohabiting, and 3% were married.

2.2. Procedures

The present study adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP). Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for the Study of Psychotherapy, School of Specialization in Brief Psychotherapies with a Strategic Approach (reference number: ISP-IRB-2023-4). Participants were invited to participate in an extensive online survey, and their completion of the survey was mandatory, ensuring no missing data. Only participants who provided informed consent were included in the study, and their participation was voluntary, without any form of compensation. The privacy and confidentiality of the participants were given utmost priority during all phases of the research.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Childhood Emotional Abuse

The assessment of adolescents' CEA was conducted using the CEA subscale of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF, Bernstein & Fink, 1998). The CTQ-SF CEA subscale has been demonstrated to possess strong validity in Italian individuals, as noted in previous research (Musetti et al., 2021). Participants were presented with five items and were asked to indicate the extent of CEA severity experienced during their childhood (e.g., "People in my family said hurtful or insulting things to me"). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). The scores for the five items were averaged, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of CEA. The internal consistency of the CEA subscale in the current study was found to be good, as indicated in

Table 1. In the current study, the internal consistency was good (

Table 1).

2.3.2. Neuroticism

To measure neuroticism, the Neuroticism subscale of the Italian version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-N; John et al., 1991; Ubbiali et al., 2013) was utilized. The BFI-N consists of 8 items designed to assess traits related to neuroticism. Examples of the items include statements such as "I see myself as someone who can be tense." Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score on the BFI-N indicates a higher level of neuroticism. In the current study, the internal consistency was good (

Table 1).

2.3.3. Perfectionism

Perfectionism was evaluated using the Italian version of Short Almost Perfect Scale (SAPS; Loscalzo et al., 2018; Rice et al., 2014). This self-report questionnaire comprises 8 items specifically designed to measure perfectionism traits. Examples of items include statements such as "I expect the best from myself." Participants were asked to rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the SAPS indicate higher levels of perfectionism. In the current study, the internal consistency was good (

Table 1).

2.3.4. Workaholism

To measure workaholism, the Italian version of the Bergen Work Addiction Scale (BWAS; Andreassen et al., 2012; Molino et al., 2022) was employed. The BWAS is a self-report questionnaire comprising 7 items specifically designed to assess workaholism. Participants indicate their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Sample items include "How often during the last year have you thought of how you could free up more time to work?" Higher scores on the BWAS indicate higher levels of workaholism. In the current study, the internal consistency was good (

Table 1).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and initial analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS. The primary analyses, on the other hand, were performed using the lavaan package in RStudio. A structural equation modeling (SEM) with latent variables was employed to examine the mediation model. In this model, CEA served as the predictor variable, while neuroticism and perfectionism acted as mediators, and workaholism was the outcome variable. To assess the significance of the indirect effects, the bootstrap-generated bias-corrected confidence interval approach with 5000 resamples was utilized. Lastly, a multigroup path analysis (MGPA) was performed, considering gender as the group variable, to examine potential variations in structural paths between boys and girls.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

The descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables analyzed in the study are displayed in

Table 1. The means observed in this study align with those reported in previous research conducted by Kuo et al. (2015), Gegieckaite and Kazlauskas (2022), Wang et al. (2019), and Morkevičiūtė and Endriulaitienė (2022).

3.2. Mediation model

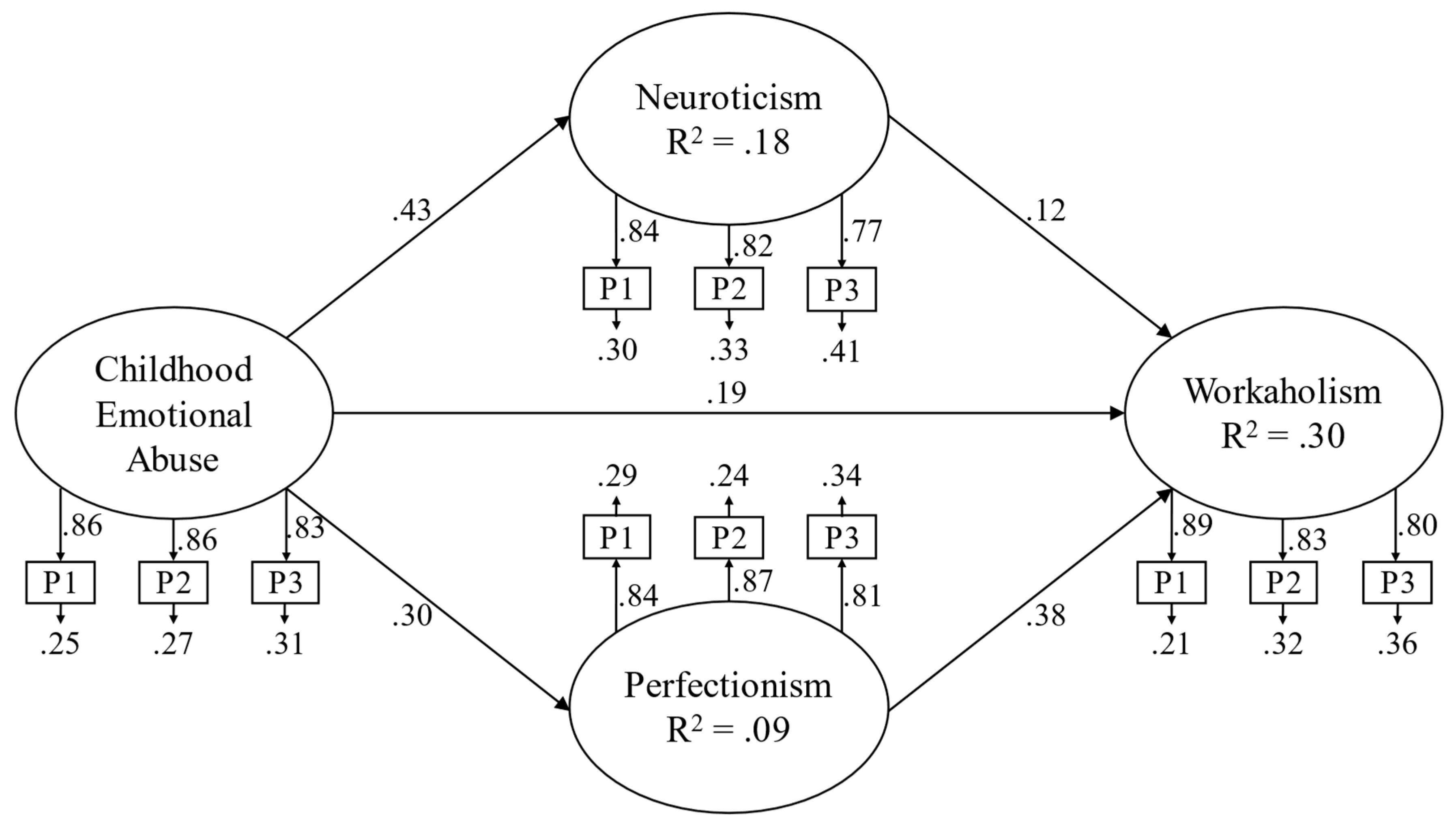

The proposed model was assessed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with latent variables (

Figure 2). The findings indicated a good fit between the model and the data, with χ2(48) = 231.88, p < .001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05 – .07), and SRMR = .04. Notably, significant direct and indirect paths were observed among all the variables examined (

Table 2).

3.3. Moderating role of gender

To explore potential variations in structural paths between boys and girls, a multigroup path analysis (MGPA) was conducted on the proposed model. Initially, a constrained model was tested, where the paths of the hypothesized model were set equal across both groups. The constrained model yielded χ2(101) = 295.99, p < .001, and CFI = .98. Subsequently, an unconstrained model was tested, allowing all paths to vary between the two groups. The unconstrained model produced χ2(96) = 286.18, p < .001, and CFI = .98. The fit indices of the unconstrained model did not significantly differ from the constrained model, indicating structural equivalence across both groups, Δχ2(5) = 9.87, p = .08, ΔCFI < .001. Thus, the relationships were found to be comparable between boys and girls.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to examine the potential mediating role of neuroticism and perfectionism in the relationship between CEA and workaholism. The findings of this study indicate that neuroticism and perfectionism do indeed mediate the association mentioned above. These results carry significant implications for enhancing our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the development of workaholism in individuals.

The association between CEA and maladaptive personality traits is intricate and multifaceted. Previous research consistently demonstrates a positive correlation between CEA and neuroticism, indicating that individuals who have experienced emotional abuse during their childhood tend to exhibit higher levels of neuroticism compared to those who have not experienced such abuse (Schwandt et al., 2012). This connection can be attributed to the chronic emotional distress and trauma associated with CEA, which disrupts the healthy development of emotional regulation and may contribute to increased emotional sensitivity and instability (Barahmand et al., 2016; Barberis et al., 2019). The cognitive and emotional processing of individuals who have experienced emotional abuse is shaped, leading to the formation of maladaptive beliefs and coping strategies characteristic of neuroticism. For example, negative self-perceptions, low self-esteem, and heightened vulnerability are common cognitive and emotional patterns observed in individuals who have experienced emotional abuse (Hymowitz et al., 2017). These patterns contribute to the manifestation of neuroticism traits, including anxiety, worry, and emotional volatility (Schwandt et al., 2012). Additionally, CEA can have long-lasting effects on neural pathways and brain structures involved in emotion regulation and stress response. Neuroimaging studies have identified alterations in brain regions associated with emotion processing and regulation among individuals who have experienced CEA (Abercrombie et al., 2018). These neurobiological changes may further contribute to the development of neuroticism traits and heightened emotional reactivity.

Evidence indicates a positive correlation between CEA and perfectionism. Individuals who have encountered CEA are more prone to displaying perfectionistic tendencies in comparison to those who have not experienced such abuse (Miller & Vaillancourt, 2007). Perfectionism can function as a coping strategy for individuals who have undergone CEA. It is possible that they develop perfectionistic tendencies as a means to restore a sense of control, self-value, and recognition (Hill et al., 2011). The pursuit of perfection can serve as a mechanism for shielding oneself from criticism or rejection and for establishing a sense of competence and self-worth. Furthermore, individuals who have endured emotional abuse during childhood may develop a tendency to seek external validation as a way to compensate for the absence of emotional support and validation received during their developmental years (Flett et al., 2014). The motivation behind perfectionism often stems from a yearning to receive recognition, approval, and acceptance from others. Individuals believe that attaining perfection will result in validation and a feeling of being valued. Additionally, CEA can contribute to the formation of cognitive distortions, such as all-or-nothing thinking and excessive self-criticism (Glassman et al., 2007). These distorted patterns of thinking can intensify perfectionistic inclinations, as individuals hold the belief that anything less than perfection is unacceptable. They tend to view mistakes or imperfections as personal failures.

Consequently, maladaptive personality traits like neuroticism and perfectionism may contribute to the development of workaholism patterns in individuals who have experienced emotional abuse. Neurotic individuals often encounter heightened levels of anxiety, stress, and self-doubt, which may motivate their continuous need to work and achieve as a means to alleviate these negative emotions. Work can function as a distraction or a coping mechanism for managing their inherent emotional instability (Therthani et al., 2022). Furthermore, individuals with higher levels of neuroticism are more susceptible to experiencing job stress and burnout. Neurotic individuals may struggle with effectively handling work-related stressors and are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion and dissatisfaction with their work (Sosnowska et al., 2019). Workaholism, characterized by its demanding nature and excessive work hours, can worsen these negative consequences and contribute to the onset of burnout. Moreover, individuals with higher levels of neuroticism are inclined to employ maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as avoidance or overcompensation, which can further compound the detrimental effects of workaholism (Holland, 2008). For individuals high in neuroticism, workaholism can be perceived as a strategy of overcompensation, driven by their desire for continuous validation, achievement, and a sense of control, as a means to cope with their emotional distress. By immersing themselves in work, they may experience temporary relief from anxiety. However, this intense preoccupation with work may result in neglecting other crucial areas of life (Reiner et al., 2019).

Perfectionism and workaholism are frequently characterized by a shared motivation for accomplishment and triumph. Perfectionists establish remarkably high expectations for themselves and exert significant efforts to meet or surpass those expectations in their professional endeavors. This relentless pursuit of perfection can result in an excessive fixation on work, characterized by extended working hours and an intense drive to complete tasks flawlessly (Kun et al., 2020). Perfectionists often harbor a profound fear of failure or committing errors. This fear serves as a driving force behind their adoption of workaholic tendencies, as they perceive excessive work as a way to evade the possibility of experiencing failure (Wojdylo et al., 2013). They may hold the belief that engaging in excessive work and exerting stringent control over their tasks will minimize the chances of committing errors or facing criticism, thereby reinforcing their inclination toward workaholism. Additionally, perfectionists frequently impose significant pressure on themselves to attain their ideal standards, contributing to their workaholic tendencies (Kun et al., 2021). They may hold the belief that their sense of self-worth depends on meeting these standards, resulting in an irresistible urge to work excessively in order to guarantee flawless outcomes. This self-imposed pressure can intensify workaholic behaviors, as perfectionists may encounter difficulties in establishing healthy boundaries between their work and personal life (Burke et al., 2009). Perfectionists may place such a high priority on work that they inadvertently neglect their personal well-being and significant social relationships. This disregard for personal needs and connections can intensify tendencies towards workaholism, as the relentless pursuit of perfection becomes all-encompassing, resulting in other aspects of life being compromised (Reiner et al., 2019).

The second aim of the study was to examine whether the proposed model remained consistent across genders. The findings indicated that the structural relationships within the model were consistent and did not differ between men and women. This suggests that the mediating effects of neuroticism and perfectionism in the association between CEA and workaholism may hold equal significance for both genders. These results contribute to the generalizability of our findings across genders. Previous research has identified variations in the relationship between workaholism and other psychological factors when comparing boys and girls (Aziz & Cunningham, 2008; Burgess et al., 2006; Burke & Berge Matthiesen, 2009). The results of this study indicate that variations in workaholism among genders can be partially explained by individual differences in CEA, neuroticism, and perfectionism.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Our research has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design of the study makes it difficult to establish the causal direction of the relationships observed. It would be valuable to conduct longitudinal investigations to validate and better understand these results over time. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of interpretive bias. Participants' subjective perceptions and interpretations may influence their responses. To mitigate this bias, future studies could consider incorporating data from multiple sources, such as objective measures or reports from other individuals, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the variables under investigation. Third, it is important to note that our study exclusively relied on online data collection. This may have limited the generalizability of our findings to individuals who do not have access to the internet or who are less likely to engage in online surveys. To improve the precision and representativeness of future research, it would be beneficial to incorporate diverse data sources, such as in-person interviews or data from offline samples. This would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon across different populations and contexts.

From a clinical standpoint, the findings of the present study underscore the significance of early detection and intervention for individuals who have experienced CEA. Mental health professionals can utilize the proposed model as a valuable tool to identify individuals who are susceptible to developing workaholism and implement appropriate therapeutic strategies. It is crucial to address the underlying emotional wounds associated with CEA in order to prevent the adoption of maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as workaholism. Additionally, the identification of neuroticism and perfectionism as mediators emphasizes the importance of targeting these personality traits in therapeutic interventions to reduce the risk of workaholism. Moreover, adopting trauma-informed approaches that create a safe and supportive environment is vital for facilitating healing and promoting recovery. In terms of research, the mediation model presented in this study underscores the importance of conducting longitudinal investigations to establish the temporal relationships among the variables. By following individuals over an extended period, researchers can examine the long-term effects of CEA on the development of neuroticism, perfectionism, and ultimately workaholism. Furthermore, there is a need for intervention studies to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches that specifically target neuroticism and perfectionism. Such studies would provide valuable insights into whether reducing these personality traits can help mitigate the risk of workaholism and guide the development of prevention strategies.

6. Conclusions

The current study provides valuable insights into the intricate dynamics between CEA, neuroticism, perfectionism, and workaholism. Comprehending these connections can serve as a valuable resource for clinical practitioners, providing guidance for effective interventions. Moreover, this understanding can inform future research endeavors with the objective of mitigating the adverse consequences of CEA and its associated psychological factors on workaholism.

Author Contributions

Valeria Verrastro: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft. Francesca Cuzzocrea: Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Danilo Calaresi: Resources, Visualization, Validation, Project Administration, Supervision. Valeria Saladino: Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP) and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for the Study of Psychotherapy, School of Specialization in Brief Psychotherapies with a Strategic Approach (reference number: ISP-IRB-2023-4).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abercrombie, H. C., Frost, C. P., Walsh, E. C., Hoks, R. M., Cornejo, M. D., Sampe, M. C., Gaffey, A. E., Plante, D. T., Ladd, C. O., & Birn, R. M. (2018). Neural Signaling of Cortisol, Childhood Emotional Abuse, and Depression-Related Memory Bias. Biological psychiatry. Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 3(3), 274–284. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Hetland, J., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a work addiction scale. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 53(3), 265–272. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C. S., Hetland, J. Ø. R. N., & Pallesen, S. T. Å. L. E. (2012). Coping and workaholism. Results from a large cross-occupational sample. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 19, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S., & Cunningham, J. (2008). Workaholism, work stress, work-life imbalance: exploring gender's role. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(8), 553-566. [CrossRef]

- Barahmand, U., Khazaee, A., & Hashjin, G. S. (2016). Emotion dysregulation mediates between childhood emotional abuse and motives for substance use. Archives of psychiatric nursing, 30(6), 653-659. [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., Calaresi, D., & Gugliandolo, M. C. (2019). Relationships among Trait EI, Need Fulfilment, and Performance Strategies. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology, 4(3), 50. [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., Martino, G., Calaresi, D., & Žvelc, G. (2020). Development of the Italian Version of the Test of Object Relations-Short Form. Clinical neuropsychiatry, 17(1), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Bullis, J. R., & Carl, J. R. (2014). The origins of neuroticism. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 481-496. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Burgess, Z., Burke, R. J., & Oberklaid, F. (2006). Workaholism among Australian psychologists: gender differences. Equal Opportunities International, 25(1), 48-59. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. J., & Berge Matthiesen, S. (2009). Workaholism among Norwegian journalists: gender differences. Equal Opportunities International, 28(6), 452-464. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. J., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Work motivations, satisfactions, and health among managers: Passion versus addiction. Cross-Cultural Research, 43(4), 349-365. [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P. L. (2014). Perfectionism and interpersonal orientations in depression: An analysis of validation seeking and rejection sensitivity in a community sample of young adults. Psychiatry, 77(1), 67-85. [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive therapy and research, 14, 449-468. [CrossRef]

- Gegieckaite, G., & Kazlauskas, E. (2022). Do emotion regulation difficulties mediate the association between neuroticism, insecure attachment, and prolonged grief?. Death studies, 46(4), 911–919. [CrossRef]

- Glassman, L. H., Weierich, M. R., Hooley, J. M., Deliberto, T. L., & Nock, M. K. (2007). Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behaviour research and therapy, 45(10), 2483-2490. [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, I., & Snir, R. (2003). Workaholism: Its definition and nature. Human relations, 56(3), 291-319. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Appleton, P. R. (2011). The relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 238–242. [CrossRef]

- Holland, D. W. (2008). Work Addiction: Costs and Solutions for Individuals, Relationships and Organizations. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 22(4), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hymowitz, G., Salwen, J., & Salis, K. L. (2017). A mediational model of obesity related disordered eating: The roles of childhood emotional abuse and self-perception. Eating Behaviors, 26, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). Big Five Inventory (BFI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Kun, B., Takacs, Z. K., Richman, M. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Work addiction and personality: A meta-analytic study. Journal of behavioral addictions, 9(4), 945-966. [CrossRef]

- Kun, B., Urbán, R., Bőthe, B., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Kökönyei, G. (2020). Maladaptive rumination mediates the relationship between self-esteem, perfectionism, and work addiction: A largescale survey study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(19), 7332. [CrossRef]

- Loscalzo, Y., Rice, S. P. M., Giannini, M., & Rice, K. G. (2019). Perfectionism and Academic Performance in Italian College Students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(7), 911–919. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. L., & Vaillancourt, T. (2007). Relation between childhood peer victimization and adult perfectionism: are victims of indirect aggression more perfectionistic?. Aggressive behavior, 33(3), 230–241. [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Kovalchuk, L. S., Ghislieri, C., & Spagnoli, P. (2022). Work Addiction Among Employees and Self-Employed Workers: An Investigation Based on the Italian Version of the Bergen Work Addiction Scale. Europe's journal of psychology, 18(3), 279–292. [CrossRef]

- Morkevičiūtė, M., & Endriulaitienė, A. (2022). Understanding Work Addiction in Adult Children: The Effect of Addicted Parents and Work Motivation. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(18), 11279. [CrossRef]

- Musetti, A., Starcevic, V., Boursier, V., Corsano, P., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Childhood emotional abuse and problematic social networking sites use in a sample of Italian adolescents: The mediating role of deficiencies in self-other differentiation and uncertain reflective functioning. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(7), 1666–1684. [CrossRef]

- Reiner, S. M., Balkin, R. S., Gotham, K. R., Hunter, Q., Juhnke, G. A., & Davis, R. J. (2019). Assessing life balance and work addiction in high-pressure, high-demand careers. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(4), 409-416. [CrossRef]

- Rice, K. G., Richardson, C. M., & Tueller, S. (2014). The short form of the revised almost perfect scale. Journal of personality assessment, 96(3), 368–379. [CrossRef]

- Saladino, V., Eleuteri, S., Verrastro, V., & Petruccelli, F. (2020). Perception of Cyberbullying in Adolescence: A Brief Evaluation Among Italian Students. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 607225. [CrossRef]

- Saladino, V., Mosca, O., Petruccelli, F., Hoelzlhammer, L., Lauriola, M., Verrastro, V., & Cabras, C. (2021). The Vicious Cycle: Problematic Family Relations, Substance Abuse, and Crime in Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 673954. [CrossRef]

- Schwandt, M. L., Heilig, M., Hommer, D. W., George, D. T., & Ramchandani, V. A. (2012). Childhood Trauma Exposure and Alcohol Dependence Severity in Adulthood: Mediation by Emotional Abuse Severity and Neuroticism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(6), 984–992. [CrossRef]

- Shapero, B. G., Black, S. K., Liu, R. T., Klugman, J., Bender, R. E., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2013). Stressful Life Events and Depression Symptoms: The Effect of Childhood Emotional Abuse on Stress Reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 209–223. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. M., Vidovic, V., Sherry, S. B., & Saklofske, D. H. (2017). Self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism add incrementally to the prediction of suicide ideation beyond hopelessness: A meta-analysis of 15 studies. Handbook of suicidal behaviour, 349-369. [CrossRef]

- Sosnowska, J., De Fruyt, F., & Hofmans, J. (2019). Relating neuroticism to emotional exhaustion: A dynamic approach to personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2264. [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S., Lisha, N., & Griffiths, M. (2011). Prevalence of the addictions: a problem of the majority or the minority?. Evaluation & the health professions, 34(1), 3–56. [CrossRef]

- Therthani, S., Balkin, R. S., Perepiczka, M., Silva, S., Hunter, Q., & Juhnke, G. A. (2022). Assessing personality traits, life balance domains, and work addiction among entrepreneurs. The Career Development Quarterly, 70(3), 190-201. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A. E., & Kaplan, C. A. (1996). Childhood emotional abuse. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(2), 143-148. [CrossRef]

- Ubbiali, A., Chiorri, C., & Hampton, P. (2013). Italian big five inventory. Psychometric properties of the Italian adaptation of the big five inventory (BFI). BPA-Applied Psychology Bulletin (Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata), 59(266).

- Verrastro, V., Ritella, G., Saladino, V., Pistella, J., Baiocco, R., & Fontanesi, L. (2020). Personal and Family Correlates to Happiness amongst Italian Children and Pre-Adolescents. International journal of emotional education, 12(1), 48-64.

- Wang, K. T., Sheveleva, M. S., & Permyakova, T. M. (2019). Imposter syndrome among Russian students: The link between perfectionism and psychological distress. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Shi, W., & Jin, G. (2019). Effect of childhood emotional abuse on aggressive behavior: a moderated mediation model. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(8), 929-942. [CrossRef]

- Wojdylo, K., Baumann, N., Buczny, J., Owens, G., & Kuhl, J. (2013). Work Craving: A Conceptualization and Measurement. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(6), 547–568. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).