1. Introduction

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a genetically modified virus from the coronavirus family, SARS-CoV-2. The disease, in 2020, was considered a pandemic and recognized as a threat to human health. Most people infected with the virus had mild to moderate respiratory illness and usually recover without needing hospital treatment [

1].

According to the World Health Organization [

1], the most common symptoms are cough, fever, tiredness and loss of taste or smell. and chest pain, and death may even occur. The virus that causes the disease could be transmitted through two different routes. The most significant is through direct contact in which the virus is transmitted from person to person, through the respiratory route, when they are in close contact (less than two meters). In those cases, the disease may be caused by the spread of respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, which can be inhaled into the lungs. The second route of transmission is through indirect contact, in which the hands come into contact with a surface or object contaminated with the virus and then contact the mouth, nose or eyes [

2]. On an individual basis, the main measures used to combat the COVID-19 pandemic consisted of simple gestures to prevent the transmission of the virus, namely regular and careful washing and/or disinfection of hands, respect for respiratory etiquette, vaccination against the virus [

3], keeping a safe distance even if people do not appear to be sick, use a properly adjusted mask when physical distance is not possible or when there is no adequate ventilation in the environment, preference for open and well-ventilated places, to the detriment of closed spaces and crowds of people and isolation and immediate testing in case of suspected illness [

1].

Also at work, COVID-19 has presented an unprecedented global health challenge, demanding rapid and extensive implementation of infection control measures. Among these measures, the frequent and stringent use of disinfectant products has become a hallmark of the pandemic response, serving as a critical tool in preventing the virus’s spread. This context, lead to a massive increase in the production and use of disinfectant products containing active ingredients such as ethanol, isopropanol, hydrogen peroxide, quaternary ammonium compounds, and sodium hypochlorite. These products are used for surface disinfection, hand sanitization, and personal protective equipment decontamination. Essential workers, particularly healthcare professionals, cleaners, and first responders, have been at the forefront of using these products extensively. Prolonged and repeated skin contact with these disinfectants can lead to various adverse health effects [

4].

While these disinfectants play a vital role in reducing the risk of viral transmission in various settings, including healthcare facilities, public spaces, and workplaces, their frequent and prolonged use has raised concerns about the potential adverse health effects on those tasked with their application. Specifically, the impact of occupational skin exposure to disinfectant products has emerged as an area of growing concern.

The main objective of this study was systematize the scientific evidence about occupational dermatological exposure to hand sanitizers, considering the increased use of these products in the workplace contexts. Through this review, we intend to analyze the effects of using hand sanitizers depending on the use frequency and associated symptoms, during COVID-19 pandemic, in order to identify gaps on the literature about the management and implementation of the contingency plans in the workplaces.

2. COVID-19 in the Workplace

The pandemic negatively impacted the world of work economically and socially, with workers absenteeism increase due to being sick, taking care of sick family members, staying with their children due to closed daycare centers and schools or even because they were afraid to work for fear of possible exposure [

3]. Indeed, in the context of work, COVID-19 triggered profound and rapid changes at work, imposed demanding and complex challenges in terms of the health and safety of workers and highlighted the relevance of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) activities. In order to control the COVID-19 crisis, preventing or avoiding new outbreaks and, consequently, additional economic disturbances, companies implemented effective occupational prevention and control measures, in accordance with the legal requirements established by the competent authorities. Occupational risk assessments included the biological risk, to protect vulnerable workers against COVID-19 [

5].

Companies have implemented measures at all levels, which correspond, almost entirely, to the measures referred to individually, namely the cleaning and disinfection of hands and surfaces. Regarding the hands, the indications stated that to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from the surface of the skin, preventing it from spreading in the workplace, namely through the handling and contact, workers should wash their hands with soap and water (for at least 20 seconds), or use an alcohol-based antiseptic solution with 70% alcohol and perform antiseptic hand rubbing.

Hand washing must be thorough and regular, namely before starting work, before eating, frequently during the work shift, especially after contact with co-workers or customers, after going to the bathroom, after contact with secretions, excretions and body fluids, after contact with potentially contaminated objects (gloves, clothing, masks, used tissues, waste) and immediately after removing gloves and other protective equipment [

1]. Whenever hand washing is not possible, workers should resort to the use of alcohol-based antiseptic solution and perform hand rubbing, covering all surfaces of the hands, rubbing them until they are dry.

3. Alcohol-Based Disinfectants and Types of Skin Lesions Associated with Their Use

Several national and international organizations have issued guidelines for the use of disinfectants in the workplace, to minimize the risk of contagion. In this sense, the WHO recommended that companies should ensure the placement of hand disinfectant product dispensers in prominent and strategic locations around the workplace and accessible to all employees, along with communication materials to promote hand hygiene [

6].

There are several types and forms of disinfectants, such as gel, foam, cream, spray, wipes, among others. However, for regular hand disinfection, gel formulations are the most popular and their chemical composition can be quite diverse [

7].

Alcohol-based antiseptic solutions are generally made up of a mixture of ethanol and 60%-70% isopropyl alcohol (or a single alcohol) with dermo protective substances and excipients [

8]. Hand sanitizers containing 60-95% alcohol, are more effective compared to lower or even higher concentration hand sanitizers as the proteins are not easily denatured in the absence of water. Furthermore, pure alcohol or higher concentrations would evaporate too quickly to exert any disinfectant effect. WHO recommended formulations containing 80% v/v ethanol or 75% v/v isopropyl alcohol. The most commonly used concentrations vary between 60 and 80% [

9]. They have bactericidal, fungicidal and virucidal properties of fast action, reducing the transient flora of the hands and the risk of infections. The mechanism of action is through protein denaturation, i.e., it damages lipid structures of microbial cell membranes. Its disinfectant and cleaning actions, complements the mechanical removal of microorganisms [

8].

While hand washing and disinfection recommendations can be effective against the spread of infectious diseases, these behaviors can alter the integrity of the skin resulting in skin barrier dysfunction and causing significant injury.The diseases most commonly associated with the use of alcohol-based disinfectants are irritant contact dermatitis and allergic dermatitis [

9]. Dermatitis is a broad term that encompasses many different symptoms such as itching, flaking and dry skin, redness, swelling, blistering, and more. Eczema is synonymous with dermatitis, however, it is generally used to designate atopic dermatitis. Irritant contact dermatitis occurs when the skin comes into contact with a toxic substance or chemical causing skin damage. Dermatitis can become chronic if persist for a long period of time in which the hands are the most susceptible place because they come into contact several times with foreign substances.

4. Materials and Methods

The methodology chosen for carrying out this study was a rapid review of the literature in which similar materials from different authors are gathered for further analysis. “A rapid review is a form of knowledge synthesis that accelerates the process of conducting a traditional systematic review through streamlining or omitting various methods to produce evidence for stakeholders in a resource-efficient manner [

10].” This methodology enables an evaluation of existing literature using systematic review methods, whilst allowing for a reduction in the breadth and depth of a full systematic review [

11]. The WHO guidelines for rapid reviews states that the literature search can be limited to two or more databases with additional limits on date, language and study design.[

12] Although potentially relevant research studies might not be identified using this approach, there is evidence to show that conclusions determined from rapid reviews are similar to conclusions reached in more comprehensive reviews [

13]. In this case, it allowed synthesizing a set of information with scientific evidence to define the next studies to be carried out and to identify existing gaps in this research topic. The objective was to carry out a survey of studies already carried out in the context of occupational dermatological exposure, caused by the increased use of alcohol-based disinfectant products, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This review was based on the protocol developed by Domingos et al. [

14].

4.1. Search Strategy

The collection of articles was carried out in the Web of Science database, which searches simultaneously in four different databases, namely, Web of Science Core Collection, Medline, Scielo and Current Content Connect. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) was used to search for keywords and, simultaneously, the Boolean terms “AND” and “OR” were used to enable a search strategy through the combination of several keywords. The terms and combinations used to carry out the search were:

((((((TI=(SARS-COV-2)) OR TI=(COVID-19)) AND TI=(Skin Exposure)) OR TI=(Skin Exposure Assessment)) AND TI=(Alcohol disinfectants)) OR TI=(Hand Sanitizers)) OR TI=(Surface Disinfectants) and Covid 19 or Hand Sanitizers or Humans or Disinfectants or Ethanol or Sars Cov 2 or Hand Disinfection or Hand Hygiene or Alcohols or Dermatitis Allergic Contact or Dermatitis Occupational or Skin Absorption or Skin (MeSH Headings)

The year of publication (2019-2022) and the language (English) and the available article abstract were defined as limiting factors. Additionally, the bibliographic references of the articles returned by the survey were analyzed, to allow the inclusion of more articles relevant to the study.

4.2. Selection Process and Eligibility Criteria

The results returned by the search were organized in a table and duplicates were subsequently removed. For the selection of studies, initially, only the titles and abstracts of the articles obtained through the search strategy were analyzed. Those who were considered eligible, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were selected for further full analysis. The eligibility criteria were applied by two researchers.

Eligible studies were descriptive or analytical studies reporting occupational dermal exposure to alcohol-based formulations used to control SARS-CoV-2 transmission, in activity. Only articles written in English or Portuguese were included. The exclusion criteria initially proposed were studies outside the occupational scope, studies not related to COVID-19, studies not related to alcohol-based disinfectant products and literature reviews.

4.3. Data Extraction

After selecting the included studies, relevant data for the purpose of the study were collected. Data were collected on the year of publication and authors; the study design; the sample (number of individuals, gender distribution, age averages), study location (sector of activity), applied methodology (questionnaire, clinical observation, complementary diagnostic exam), information about the disinfectant(s) and associated skin injury.

5. Results

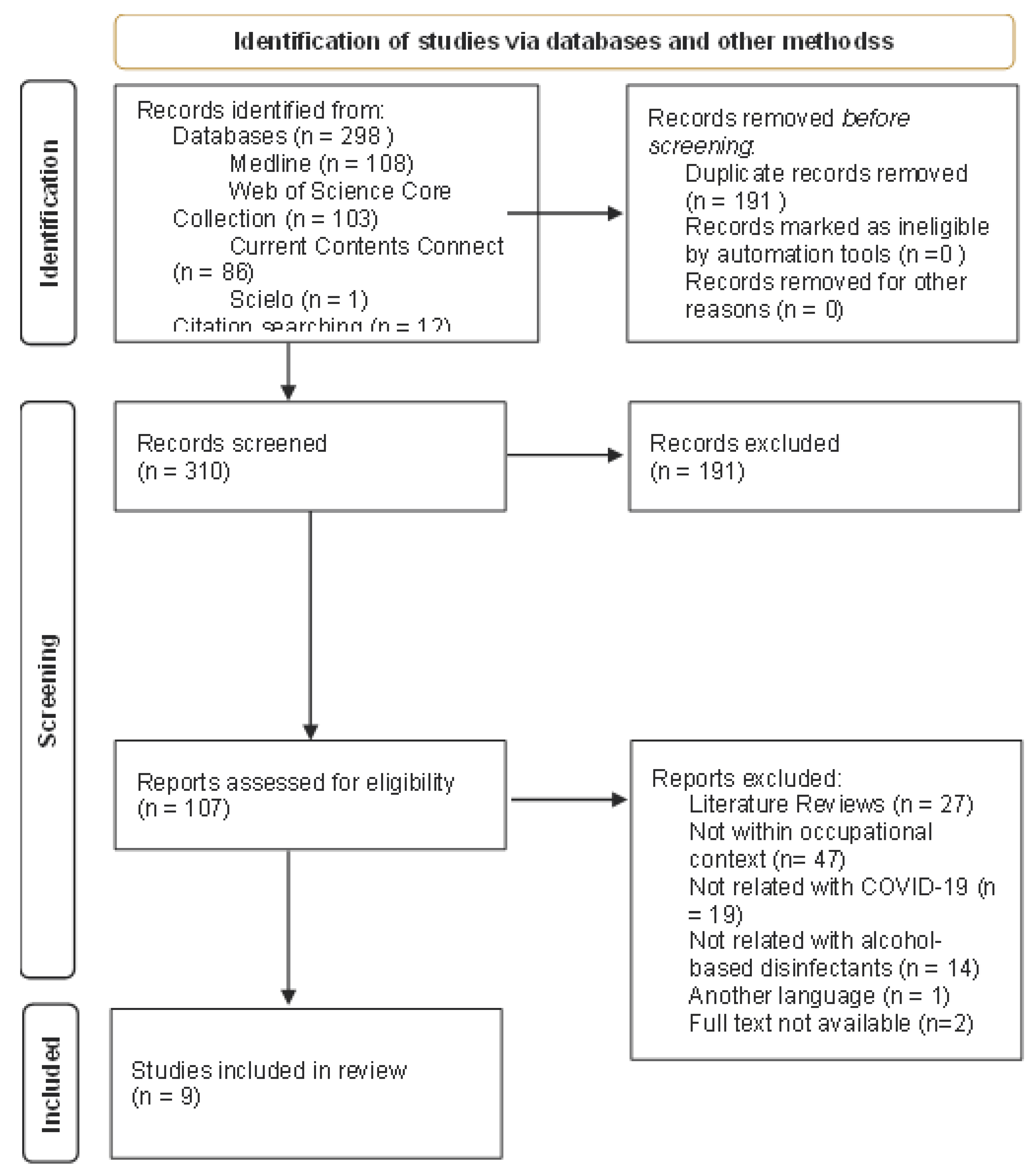

After applying the research data, a total of 298 articles resulted in which, after removing duplicates, 108 articles remained. These 108 articles went on to the screening phase, to which another 12 researched by alternative route were added, making a sample of 120 articles. After analyzing the title and content of the abstract, 111 articles were excluded with justification. Most were studies related to alcohol-based disinfectants, but related to another type of exposure, such as ocular exposure or ingestion (without skin contact). In addition, several studies addressed accidental exposure to this type of disinfectant by children, therefore not fitting in the context of occupational exposure. The remaining were studying the effectiveness of certain disinfectant formulations for the Sars-CoV-2 virus. A total of 9 studies met the established inclusion criteria. The results of the research carried out are described in

Figure 1.

Table 1 presents the relevant characteristics of each study included in the review. This table is organized by study, in which the country and place where it was carried out are described for each one. It also shows the number of participants in the study, the applied methodology, information regarding the composition of the disinfectant used and its frequency of use per work shift. Finally, the identified skin lesion and the percentage of reported symptom prevalence.

By analyzing

Table 1, all studies focus on the exposure of health professionals [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. However, most focus on the analysis of exposure in various hospital services [

15,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23], while only three studies were specifically developed in health units associated with the fight against COVID-19 [

16,

18,

19].

Regarding the methodology used in each study, in six studies data were collected by questionnaires [

15,

18,

19,

20,

22], two studies, in addition to the questionnaire, carried out dermatological examinations [

16,

17], one study had clinical observation by a dermatologist, but without specific examinations [

21], and finally, a study was carried out by self-diagnosis and subsequent referral for consultation [

23].

With regard to disinfectants, all studies refer to the use of alcohol-based disinfectants without specifying the constituents [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The frequency of use of disinfectants was reported by most studies, three refer that disinfection per work shift was performed more than 10 times or from 10 to 20 [

19,

22,

23], one study claims 15 to 20 times [

15], three studies report between 20 and 30 disinfections [

16,

18,

21] and the remaining two studies did not present data regarding this indicator [

17,

20].

Finally, the identified injuries were described differently between the authors. In some studies, any symptoms that may be related to eczema or dermatitis of the hands were valued, without a diagnosis of the disease, such as itching, dry skin, erythema, scaling, among others [

15,

18,

19,

23] while the rest identified dermatological diseases in the samples. The most reported disease was irritant contact dermatitis together with atopic dermatitis, present in three studies [

16,

17,

21], two studies refer to a higher prevalence of hand eczema [

16,

22] and a study refers to hand dermatitis [

20]. The prevalence of symptoms was calculated and presented for all analyzed studies. One study presents a prevalence of 20.87% [

23] while the others obtained prevalence values greater than 50%. Four studies between 50 and 60% [

16,

17,

19,

21], one study between 60 and 70% [

22], two studies between 70 and 80% [

16,

19] and finally, one study obtained results greater than 90% [

21].

6. Discussion

This review intended to understand the dermatological effects on the hands of workers, due to the use of alcohol-based disinfectants with the aim of mitigating the transmission of COVID-19, as a public health measure, also adopted in the work context.

The selected studies were developed in a hospital context, so it is natural that the working population under study is, in its entirety, composed of health professionals, namely doctors, nurses and assistants. According to previous studies before the pandemic, which had this population as a sample, as well as the studies analyzed in this review, revealed that dermatitis of the hands is a common disease in health professionals, as they are subject to several risk factors, such as the case of frequent hand hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as disposable gloves [

19,

24,

25].

With this review, it was found that there was an increase in hand washing and disinfection with alcohol-based disinfectants compared to the pre-COVID-19 era [

15,

18], in which all studies report more of 10 disinfections per work shift, which can reach 30 times in the case of the study by Guertler et al. [

18]. Similarly, there was a worsening in the prevalence of dermatological damage compared to the time when there was no pandemic. There are studies that report an approximate prevalence of 21% [

25,

26], while the studies related to COVID-19 that were analyzed, with the exception of one, all mention a prevalence greater than 50% [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] demonstrates a significant increase, a result that would be expected due to the also significant increase in hand washing and disinfection.

On the other hand, there was a comparison between health professionals with different jobs. Some of these professionals perform their duties in care units for patients with COVID-19 and, according to the measures to prevent the disease implemented, these professionals have, from the outset, a greater use of basic disinfectants

However, according to the study by Guertler et al. [

18] the frequency of skin lesions in workers in contact with COVID-19 patients compared to workers in a different wing of the hospital, did not reveal any discrepancy between the two groups, concluding that injuries affect all health professionals in general. This result was not expected, but demonstrates that the hygiene regulations proposed by the competent authorities were implemented in all hospital units, regardless of whether professionals were in contact with COVID-19 patients or not.

Additionally, some risk factors were also studied which, together with the higher frequency of hand disinfection, increased the prevalence of skin lesions.

In this way, the study by Motamed-Rezaei et al. [

20] reveals that there is a greater propensity to develop dermatitis of the hands in female individuals and mentions as possible explanations for this result, the fact that women are more exposed to water, detergents and irritants. In turn, the study by Çelik [

15] mentions the same explanation, denoting greater exposure to these agents, both in the workplace and at home, a factor that was not included in the studies. Similarly, the study by O’Neill et al. [

21]. points to the fact that most women were nurses and assistants, and therefore their functions are more related to contact with the patient, requiring hygiene of the most frequent hands.

On the other hand, the same study by Motamed-Rezaei et al. [

20] found that there was a higher prevalence of skin damage in individuals over 40 years old, but was unable to establish a correlation between the presence of skin damage on the hands with the age of workers. The authors explained the result with the fact that older individuals have more years of experience and therefore more time of exposure to harmful agents.

Another risk factor studied was the use of PPE at the same time as hand washing and disinfection, namely the use of gloves. Several studies were in agreement in stating that the use of gloves for long periods is harmful to the skin, increasing the prevalence of lesions such as allergic dermatitis and eczema [

19,

20]. In fact, there are previous studies that confirm these results and that ensure that some chemical products that make up synthetic rubber gloves, used in hospital services, are among the most common causes of allergic contact dermatitis. [

27,

28]. In contrast, the study by Cavanagh and Wambier [

29] mentions that the use of gloves can prevent damage to the skin, however, prolonged exposure of this PPE should be avoided.

Several authors also studied the existence of previous eczema or dermatitis as a possible risk factor for the increase in skin lesions. They realized that the existence of a clinical history of eczema or another skin disease prior to the pandemic, increased the prevalence of this type of injury, with an increase in the frequency of washing and disinfection of hands [

15,

21,

23]. In line with this fact, there are several studies carried out before the existence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in the context of occupational dermatoses [

24,

25,

26].

The study by Techasatian et al. [

23], examined injuries related to the method of washing and disinfecting hands performed by workers, describing four different types. It concluded that disinfection using alcohol-based disinfectant was the one that increased the risk of eczema compared to other methods. It states that these disinfectants should be discontinued and should give way to other handwashing methods if they are available. There are other studies that present this conclusion [

16,

19,

20]. However, there are studies that support this conclusion, namely that of Çelik [

15] and O’Neill et al. [

21]. These authors claimed that although alcohol can dissolve the lipid layer hand protector, there are previous studies showing that alcohol-based disinfectants are better tolerated than detergents and water. They also mention that detergents, soap and water break the skin barrier, especially if rinsing and drying are inadequate. The study by Çelik [

15] states that hand washing is equally harmful to alcohol-based disinfectants, but that in cases where the hands are not dirty, alcohol-based disinfectants should be used because they have high microbial activity and low risk of skin damage. Cavanagh and Wambier [

29] states that disinfectants with ethanol as the main constituent should be prioritized.

No study was found on the effect of different possible constituents of disinfectants, as they were only described as alcohol-based disinfectants, with no mention of the different constituents.

In this review, it was observed that the main lesions found in the analyzed studies were irritant contact dermatitis and hand eczema, which was in line with the results of other previous studies [

24,

25,

26].

Ferguson et al. [

21] stated that occupational dermatoses are an epidemic within the pandemic and that a robust risk assessment and the implementation of preventive measures and strategies within health services are extremely necessary. These occupational diseases are responsible for a considerable number of days lost from work, so it is crucial to identify and mitigate the risk factors that lead to this type of injury. In addition, these damages have a significant impact on the lack of adherence to the hygiene measures implemented in the services in which they work [

26]. In these cases, dermatologists play a crucial role in the prevention and immediate treatment of skin problems in healthcare professionals.

7. Conclusions

With this literature review, it was not possible to achieve the objective in its entirety, since it was only possible to obtain data referring to health professionals, while the objective was to obtain results in different work contexts. In addition, it was only possible to include studies involving hand disinfectants, when it was also intended to verify the effects of surface disinfectants on the workers’ skin. Despite that, it was possible to conclude that the increase in hand disinfection through alcohol-based disinfectants also increased the prevalence of skin lesions in this activity sector. It was possible to perceive that irritant contact dermatitis along with eczema of the hands were the diseases most detected and that there are several additional risk factors that can increase the prevalence of these diseases, such as the use of gloves, being female, the frequency of hand washing, among others.

The articles found and used for this review were, for the most part, a limitation because they are descriptive studies, where only questionnaires were used and where there was a self-diagnosis of the lesions, which may have increased the prevalence in certain cases, despite the study samples be composed of health professionals.

Only one study used dermatological examinations, namely the patch test, which makes the results more objective. Another study reported that these tests were not used due to the restrictions imposed by the presence of COVID-19, which may have happened to several studies, making it a significant disadvantage.

8. Final Remarks

Lessons from this pandemic highlight the importance of understanding the implications of occupational skin exposure to disinfectant products. Several key factors make this an urgent area of investigation: 1) Increased Frequency of Exposure: The frequency of disinfectant use in workplaces and public spaces has surged dramatically during the pandemic. As a result, individuals were at a higher risk of skin exposure, which may have long-term health consequences; 2) Diverse Range of Disinfectant Products: The variety of disinfectant products available on the market, each with different active ingredients and formulations, raises questions about which chemicals are more likely to cause skin irritation, sensitization, or other adverse effects; 3) Occupational Health Implications: Healthcare workers and other essential personnel have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Understanding the risks associated with occupational skin exposure to disinfectants is crucial to ensure the well-being of those who are most exposed to these products; 4) Potential for Public Health Impact: Beyond occupational settings, there is a concern about the broader public’s exposure to disinfectants, especially with the continued use of these products even as the pandemic wanes. Ensuring that the public is aware of potential risks and proper safety measures is vital; 5) Opportunities for Mitigation: By identifying the risks and understanding the mechanisms of skin exposure-related health effects, the scientific community can develop guidelines and interventions to mitigate potential harm, making it possible to balance the necessity of disinfectant use with health and safety concerns, in all occupational contexts.

This work is a contribution to set the stage for further research and exploration of the impact of occupational skin exposure to disinfectant products in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing the urgent need for scientific inquiry and public and occupational health interventions in this critical area to be more prepared for future epidemics.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, C.C. and J.S.; methodology, C.C.; formal analysis, C.C., D.T. and J. S.; investigation, D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, D.T. and J. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. 2022. Doença do coronavírus (COVID-19). Available online: Https://Www.Who.Int/Health-Topics/Coronavirus#tab=tab_1. (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- OSHA. 2020. Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OSHA3990.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Direção Geral de Saúde. 2022. COVID-19. Available online: Https://Www.Sns24.Gov.Pt/Tema/Doencas-Infecciosas/Covid-19/. (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Jing, J.L.J.; Pei Yi, T.; Bose, R.J.C.; McCarthy, J.R.; Tharmalingam, N.; Madheswaran, T. Hand Sanitizers: A Review on Formulation Aspects, Adverse Effects, and Regulations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalhais, C.; Querido, M.; Pereira, C. C.; Santos, J. Biological risk assessment: A challenge for occupational safety and health practitioners during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. Work, 2021, 69, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2020. Considerations for public health and social measures in the workplace in the context of COVID-19. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/332050/WHO-2019-nCoV-Adjusting_PH_measures-Workplaces-2020.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Filipe, H. A. L.; Fiuza, S. M.; Henriques, C. A.; Antunes, F. E. Antiviral and antibacterial activity of hand sanitizer and surface disinfectant formulations. Int. J. Pharm., 2021, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARS Centro. 2016. Manual de Antisseticos e Desinfetantes. Available online: https://www.arscentro.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2020/06/Manual-de-Antisseticos-e-Desinfetantes.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Kumar, S.; Das, A. Hand sanitizers: Science and rationale. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol., 2021, 87, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Kamel, C.; King, V.J.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Stevens, A.; Hamel, C.; Affengruber, L. Cochrane Rapid Reviews. Interim Guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group. March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J., 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco A, et al. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2017. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/258698/9789241512763-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Watt A, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 2008, 24, 133–139.

- Domingos, C.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, A.; Carvalhais, C.; Santos, J. Occupational dermal exposure to alcohol-based disinfectant products against covid-19: a protocol for a systematic review. IFEH World Academic Conference on Environmental Health. 2021. Available online: https://ojs.vvg.hr/index.php/IFEH/article/view/91 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Çelik, V. An Overlooked Risk for Healthcare Workers Amid COVID-19: Occupational Hand Eczema. North. Clin. Istanb, 2020, 7, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, Y.; Altunay, I. K.; Aksu Çerman, A.; Inal, S.; Ugurer, E.; Sivaz, O.; Kaya, H. E.; Gulsunay, I. E.; Sekerlisoy, G.; Vural, O.; Özkaya, E. The risk of hand eczema in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do we need specific attention or prevention strategies? Contact Dermatitis, 2020, 83, 422–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, F. J.; Street, G.; Cunningham, L.; White, I. R.; McFadden, J. P.; Williams, J. Occupational dermatology in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: a report of experience from London and Manchester, UK. Br. J. Dermatol., 2021, 184, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guertler, A.; Moellhoff, N.; Schenck, T. L.; Hagen, C. S.; Kendziora, B.; Giunta, R. E.; French, L. E.; Reinholz, M. Onset of occupational hand eczema among healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Comparing a single surgical site with a COVID-19 intensive care unit. Contact Dermatitis, 2020, 83, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Song, Z.; Miao, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Dong, L.; Yang, J.; An, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhou, N.; Li, J.; Cao, J. J.; Wang, J.; Tao, J. Skin damage among health care workers managing coronavirus disease-2019. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., 2020, 82, 1215–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamed-Rezaei, O.; Sharif-Zadeh, G.; Rajabipour, H.; Jahani, F.; Lotfi, H. Hand Dermatitis among Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevalence, and Risk Factors. MedRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, H.; Narang, I.; Buckley, D. A.; Phillips, T. A.; Bertram, C. G.; Bleiker, T. O.; Chowdhury, M. M. U.; Cooper, S. M.; Abdul Ghaffar, S.; Johnston, G. A.; Kiely, L. F.; Sansom, J. E.; Stone, N.; Thompson, D. A.; Banerjee, P. Occupational dermatoses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre audit in the UK and Ireland. Br. J. Dermatol., 2021, 184, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinholz, M.; Kendziora, B.; Frey, S.; Oppel, E. M.; Ruëff, F.; Clanner-Engelshofen, B. M.; Heppt, M. v.; French, L. E.; Wollenberg, A. Increased prevalence of irritant hand eczema in health care workers in a dermatological clinic due to increased hygiene measures during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Eur. J. Dermatol., 2021, 31, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techasatian, L.; Thaowandee, W.; Chaiyarit, J.; Uppala, R.; Sitthikarnkha, P.; Paibool, W.; Charoenwat, B.; Wongmast, P.; Laoaroon, N.; Suphakunpinyo, C.; Kiatchoosakun, P.; Kosalaraksa, P. Hand Hygiene Habits and Prevalence of Hand Eczema During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Prim. Care Community Health, 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibler, K. S.; Jemec, G. B. E.; Agner, T. Exposures related to hand eczema: A study of healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis, 2012, 66, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibler, K. S.; Jemec, G. B. E.; Flyvholm, M. A.; Diepgen, T. L.; Jensen, A.; Agner, T. Hand eczema: Prevalence and risk factors of hand eczema in a population of 2274 healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis, 2012, 67, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenan, S.; Piletta, P. Hand dermatitis in healthcare workers: 15-years experience with hand sanitizer solutions. Contact Dermatitis, 2021, 84, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L. Y.; Taylor, J. S.; Sood, A.; Murray, D.; Siegel, P. D. Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Synthetic Rubber Gloves Changing Trends in Patch Test Reactions to Accelerators. Arch. Dermatol., 2010, 146, 1001–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejonckheere, G.; Herman, A.; Baeck, M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by synthetic rubber gloves in healthcare workers: Sensitization to 1,3-diphenylguanidine is common. Contact Dermatitis, 2019, 81, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, G.; Wambier, C. G. Rational hand hygiene during the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., 2020, 82, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).