Submitted:

15 February 2024

Posted:

16 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Limitations of the Existing Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Source of Data

3.2. Data Analysis

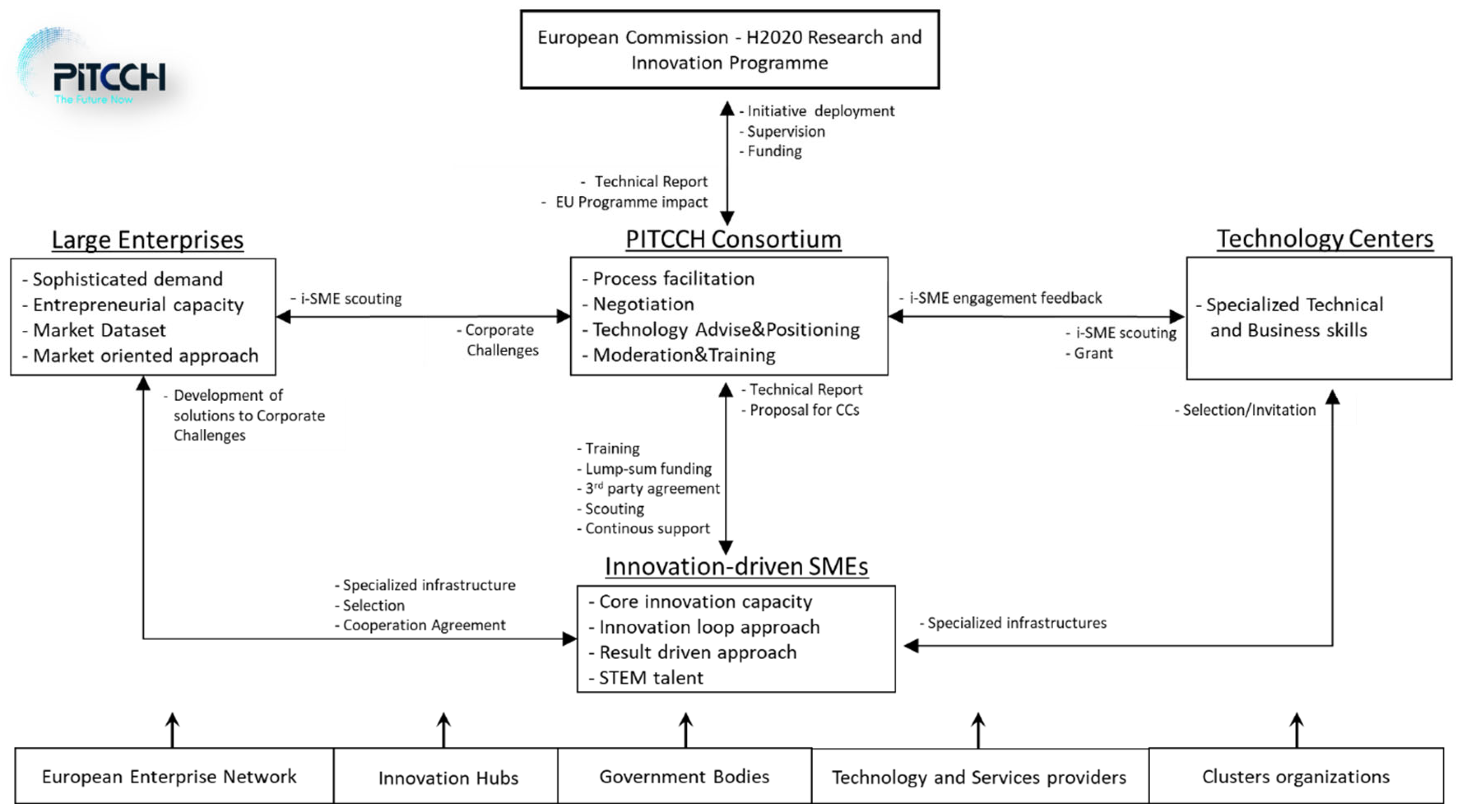

4. PITCCH Project

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The PITCCH Consortium vs. the Role of Public Governance

5.2. The Impact of Public Governance in Supporting the IE

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Praag CM, Versloot PH. What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small business economics. 2007;29(4):351–82. [CrossRef]

- Di Mattia, M. The impact of EU Cohesion Policy as a growth tool for Italian SMEs. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, Lanahan L, Miller J. Inadvertent infrastructure and regional entrepreneurship policy. M. Fritsch. Vol. Handbook of research on entrepreneurship and regional development (1st Ed., pp. 216-251). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2011.

- SMEs overview. [Internet]. European Investment Bank; 2021 [cited 2023 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.eib.org/attachments/publications/small_and_medium_enterprises_over view_2021_en.pdf.

- De Marco CE, Martelli I, Di Minin A. European SMEs’ engagement in open innovation When the important thing is to win and not just to participate, what should innovation policy do? Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020;152:119843. [CrossRef]

- Fasil CB, Biagi F, Boden M, Christensen P, Conte A, Nepelski DP, et al. Current challenges in fostering the European innovation ecosystem. Joint Research Centre (Seville site); 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hart, DM. The emergence of entrepreneurship policy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

- Hart, DM. The emergence of entrepreneurship policy: governance, start-ups, and growth in the US knowledge economy. Cambridge University Press; 2003.

- Nooteboom B, Stam E. Innovation, the economy, and policy. Micro-foundations for innovation policy. 2008;17–51. [CrossRef]

- McCann, P. The regional and urban policy of the European Union: Cohesion, results-orientation and smart specialisation. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2015.

- Clark M, Sartorius R, Bamberger M. Monitoring and evaluation: Some tools, methods and approaches. Washington, DC: The World Bank. 2004.

- Aschhoff B, Fier A, Löhlein H. Detecting behavioural additionality-an empirical study on the impact of public R&D funding on firms’ cooperative behaviour in Germany. ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper. 2006;(06–037).

- Clarysse B, Wright M, Mustar P. Behavioural additionality of R&D subsidies: A learning perspective. Research policy. 2009;38(10):1517–33. [CrossRef]

- Afcha Chavez, SM. Behavioural additionality in the context of regional innovation policy in Spain. Innovation. 2011;13(1):95–110. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. The future of public efforts to boost entrepreneurship and venture capital. Small Business Economics. 2010;35:255–64. [CrossRef]

- Radicic D, Pugh G, Douglas D. Promoting cooperation in innovation ecosystems: evidence from European traditional manufacturing SMEs. Small Business Economics. 2020;54:257–83. [CrossRef]

- Saublens, C. Regional policy for smart growth of SMEs: Guide for Managing Authorities and bodies in charge of the development and implementation of Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation. Publications Office of the European Union; 2013.

- Bettanti A, Lanati A, Missoni A. Biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystems: a stakeholder model and the case of Lombardy. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2021;1–26. [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard business review. 2006;84(4):98.

- Bogers M, Chesbrough H, Moedas C. Open innovation: Research, practices, and policies. California management review. 2018;60(2):5–16. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch DB, Belitski M. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: establishing the framework conditions. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2017;42:1030–51. [CrossRef]

- Panetti E, Parmentola A, Ferretti M, Reynolds EB. Exploring the relational dimension in a smart innovation ecosystem: A comprehensive framework to define the network structure and the network portfolio. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2020;45:1775–96. [CrossRef]

- Stam FC, Spigel B. Entrepreneurial ecosystems. USE Discussion paper series. 2016;16(13).

- Cavallo A, Ghezzi A, Balocco R. Entrepreneurial ecosystem research: Present debates and future directions. International entrepreneurship and management journal. 2019;15:1291–321. [CrossRef]

- Colombo MG, Dagnino GB, Lehmann EE, Salmador M. The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics. 2019;52:419–28. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann EE, Menter M. University–industry collaboration and regional wealth. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2016;41:1284–307. [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European planning studies. 2015;23(9):1759–69. [CrossRef]

- Acs ZJ, Estrin S, Mickiewicz T, Szerb L. Institutions, entrepreneurship and growth: the role of national entrepreneurial ecosystems. Available at SSRN 2912453. 2017.

- Auerswald PE, Dani L. The adaptive life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems: the biotechnology cluster. Small Business Economics. 2017;49:97–117. [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship theory and practice. 2017;41(1):49–72. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham JA, Menter M, Wirsching K. Entrepreneurial ecosystem governance: A principal investigator-centered governance framework. Small Business Economics. 2019;52:545–62. [CrossRef]

- Salter AJ, McKelvey M. Evolutionary analysis of innovation and entrepreneurship: Sidney G. Winter—recipient of the 2015 Global Award for Entrepreneurship Research. Small Business Economics. 2016;47:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P. Routledge revivals: Localities (1989): The changing face of urban Britain. Routledge; 2016. [CrossRef]

- Colombelli A, Paolucci E, Ughetto E. Hierarchical and relational governance and the life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics. 2019;52:505–21. [CrossRef]

- Malerba F, McKelvey M. Knowledge-intensive innovative entrepreneurship integrating Schumpeter, evolutionary economics, and innovation systems. Small Business Economics. 2020;54:503–22. [CrossRef]

- Cooke P, Uranga MG, Etxebarria G. Regional innovation systems: Institutional and organisational dimensions. Research policy. 1997;26(4–5):475–91.

- Anselin L, Varga A, Acs Z. Local geographic spillovers between university research and high technology innovations. Journal of urban economics. 1997;42(3):422–48. [CrossRef]

- Florida R, Adler P, Mellander C. The city as innovation machine. Vol. Transitions in Regional Economic Development. eBook; 2018.

- Acs ZJ, Stam E, Audretsch DB, O’Connor A. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics. 2017;49:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Autio E, Nambisan S, Thomas LD, Wright M. Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal. 2018;12(1):72–95. [CrossRef]

- Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V. The new frontier of experience innovation. MIT Sloan management review. 2003.

- Urbinati A, Chiaroni D, Chiesa V, Frattini F. The role of digital technologies in open innovation processes: an exploratory multiple case study analysis. R&d Management. 2020;50(1):136–60. [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship theory and practice. 2017;41(6):1029–55. [CrossRef]

- Hayter, CS. A trajectory of early-stage spinoff success: the role of knowledge intermediaries within an entrepreneurial university ecosystem. Small Business Economics. 2016;47:633–56. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann WH, Schlosser R. Success factors of strategic alliances in small and medium-sized enterprises—An empirical survey. Long range planning. 2001;34(3):357–81. [CrossRef]

- Carayannis EG, Grigoroudis E, Alexander JM. In pursuit of smart growth: technology transfer theories, policies and practices. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2020;45:1607–10. [CrossRef]

- Radicic D, Pugh GT, Hollanders H, Wintjes R. The impact of innovation support programmes on SME innovation in traditional manufacturing industries: an evaluation for seven EU regions. UNU-MERIT Working Paper. 2014;(2014–033).

- Attour A, Lazaric N. From knowledge to business ecosystems: emergence of an entrepreneurial activity during knowledge replication. Small Business Economics. 2020;54:575–87. [CrossRef]

- Antonioli D, Marzucchi A. Evaluating the additionality of innovation policy. A review focused on the behavioural dimension. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development. 2012;9(2–4):124–48. [CrossRef]

- Gök A, Edler J. The use of behavioural additionality evaluation in innovation policy making. Research Evaluation. 2012;21(4):306–18. [CrossRef]

- Buisseret TJ, Cameron HM, Georghiou L. What difference does it make? Additionality in the public support of R&D in large firms. International Journal of Technology Management. 1995;10(4–6):587–600.

- McCann P, Ortega-Argilés R. Smart specialisation, entrepreneurship and SMEs: issues and challenges for a results-oriented EU regional policy. Small Business Economics. 2016;46:537–52. [CrossRef]

- Davies HT, Nutley SM. What works?: Evidence-based policy and practice in public services. Policy Press; 2000.

- Mouqué, D. What are counterfactual impact evaluations teaching us about enterprise and innovation support. Regional Focus. 2012;2:2012.

- Edler J, Fagerberg J. Innovation policy: what, why, and how. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 2017;33(1):2–23. [CrossRef]

- Nepelski D, Van Roy V. Innovation and innovator assessment in R&I ecosystems: the case of the EU Framework Programme. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2021;46(3):792–827. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, MZ. The politics of innovation: Why some countries are better than others at science and technology. Oxford University Press; 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vlaisavljevic V, Medina CC, Van Looy B. The role of policies and the contribution of cluster agency in the development of biotech open innovation ecosystem. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020;155:119987. [CrossRef]

- Davis AM, Engkvist O, Fairclough RJ, Feierberg I, Freeman A, Iyer P. Public-private partnerships: Compound and data sharing in drug discovery and development. SLAS DISCOVERY: Advancing the Science of Drug Discovery. 2021;26(5):604–19. [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. Evidence-based Policy. 2006;1–208.

- Hempel K, Fiala N. Measuring success of youth livelihood interventions: A practical guide to monitoring and evaluation. 2011.

- Link AN, Vonortas NS. Handbook on the theory and practice of program evaluation. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2013.

- Gault, F. Innovation indicators and measurement: an overview. Handbook of innovation indicators and measurement. 2013;3–38.

- Ingold, T. Worlds of sense and sensing the world: a response to Sarah Pink and David Howes. Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale. 2011;19(3):313–7. [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, J. Ethnography as work: Some rules of engagement. Journal of management studies. 2011;48(1):218–34. [CrossRef]

- Autio E, Kanninen S, Gustafsson R. First-and second-order additionality and learning outcomes in collaborative R&D programs. Research Policy. 2008;37(1):59–76. [CrossRef]

- Weiblen T, Chesbrough HW. Engaging with startups to enhance corporate innovation. California management review. 2015;57(2):66–90. [CrossRef]

- Dhont-Peltrault E, Pfister E. R&D cooperation versus R&D subcontracting: empirical evidence from French survey data. Economics of Innovation and New Technology. 2011;20(4):309–41. [CrossRef]

- Backs S, Günther M, Stummer C. Stimulating academic patenting in a university ecosystem: An agent-based simulation approach. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2019;44:434–61. [CrossRef]

| Participants | Type |

|---|---|

| EU Project Officer, PITCCH consortium, researcher | Ongoing meeting |

| LEs, PITCCH Consortium, i-SMEs, researcher | Corporate challenge final meeting |

| LEs, PITCCH Consortium, researcher | i-SMEs engagement |

| LEs, PITCCH Consortium, researcher | PITCCH operations wrap-up meeting |

| PITCCH consortium, researcher (every two weeks) | Review meeting |

| PITCCH consortium, researcher | Deliverable review |

| RINA-C (weekly internal meeting), researcher | Conversations with informants |

| i-SMEs, PITCCH Consortium, researcher | Plenary session |

| i-SMEs, PITCCH Consortium, researcher | One-to-one session |

| i-SMEs, PITCCH Consortium, researcher | PITCCH day |

| Document Type | Source | Recipients |

|---|---|---|

| Deliverable | PITCCH Consortium | EU Project Officer |

| Grant Agreement | PITCCH Consortium | i-SMEs, Technology centers (TCs) |

| Customized collaboration agreement | LEs | i-SMEs, PITCCH Consortium |

| Project ppt presentation | LEs | PITCCH Consortium |

| Pitch day ppt presentations | i-SMEs | PITCCH Consortium, LEs |

| Survey to LEs | PITCCH Consortium | LEs |

| Survey to i-SMEs | PITCCH Consortium | i-SMEs |

| Technical Report | PITCCH Consortium | EU Project Officer |

| Third-party Agreement | PITCCH Consortium | i-SMEs, Technology centers (TCs) |

| 1st Round | 2nd Round | 3rd round | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PITCCH participation Funding (*) | € 10.000 | € 10.000 | /// |

| Winning Funding | € 25000 (PITCCH Consortium) |

€ 5.000 + € 10.000 (PITCCH Consortium + Grant to TCs) | € 5.000 + € 5.000 (PITCCH Consortium + LEs contributions) |

| Funding type | Lump-sum | Lump-sum + Grant | Lump-sum |

| PITCCH program participants |

|

|---|---|

| i-SMEs (registered on the PITCCH digital platform) | 512 |

| i-SMEs (which submitted a proposal to CCs) | 92 |

| Technology Centers (TCs) | 23 |

| Large Enterprises (LEs) | 26 |

| Ecosystem support organizations | 28 |

| Government bodies (regional, national public authorities, agencies, associations) | 11 |

| Technology and Services providers (consultancy firms, accelerators, etc.) | 7 |

| Innovation hubs (scientific parks, tech platforms, etc.) | 4 |

| Cluster organizations | 4 |

| Enterprise European Network | 2 |

| Innovation Challenges (CCs) | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).