1. Introduction

In 2021, the CDC reported that the 3 leading causes of death in the United States were heart disease, cancer, and COVID-19 [

1]. According to the American Cancer Society, there were 1.9 million new cancer cases and a projected 609,360 deaths from cancers in 2022 [

2]. Neoplastic cells have the ability to evade the human immune system, making cancers very difficult to diagnose and treat. Standard therapy typically consists of surgery for the solid tumors, along with radiation therapy and chemotherapy to eradicate malignant cells. Chemotherapy suffers the issues of specificity and strong side effects [

3], making it indistinguishable for malignant and healthy cells [

4]. In addition to the cytotoxic adverse effects of chemotherapy, its lengthy and expensive procedure also causes inaccessibility and compliance issues [

5]. Moreover, the heterogeneity of cancers increases the potential for drug resistance of chemotherapy, making it less effective to achieve cancer-free survival [

3,

6]. In contrast, precision medicine addresses these problems based on the genomic, environmental, and lifestyle differences in each patient, thus showing effectiveness for about 75% of cancer patients who fail from standard chemotherapy [

6]. Among many different types of cancer therapies through precision medicine [

7], monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are widely used for targeted therapy and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy [

8].

mAbs have been shown to be effective in targeting tumor cells directly or to modulate the human immune system for anti-tumor immunity [

8]. mAbs are effective on various immunological and cell signaling pathways, such as T cell activation checkpoint (e.g., PD-1 and CTLA-4), angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF, VEGFR, etc.), and growth factors (e.g., EGF, EGFR, FGFR, etc.). Ramucirumab is a monoclonal antibody that antagonizes VEGFR-2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. VEGFR-2 plays a primary role in mediating the angiogenic and tumorigenic effects of VEGF [

9]. Currently, ramucirumab is FDA-approved to be used alone or in combination with other drugs to treat metastatic colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma [

10]. Although ramucirumab is not considered to be first-line treatment for those neoplastic conditions, it has been shown to be significant in improving prognosis and prolonging survival [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Although ramucirumab is very effective, it is not widely accessible and affordable to all patients, causing a big burden on healthcare quality and equality.

In the United States of America (USA), health insurance and coverage influence the outcomes of healthcare, including diagnosis, prognosis, and quality of life for patients [

15,

16,

17]. Medicaid is a US federal government program that provides affordable, low-cost, or free healthcare to low-income American individuals and families, those with disabilities, pregnant women, and the elderly [

18]. Patients with low socioeconomic status (SES) are typically eligible for Medicaid, whereas those who do not qualify may turn to Purchased insurance instead (e.g., Aetna, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, Kaiser Permanente, etc.). Medicaid expansion (MES) due to the Affordable Care Act has reduced racial disparities in healthcare and improved cancer diagnosis and treatment [

19]. Specifically, MES resulted in statistically significant decreases in chemotherapy delays for African American and Hispanic breast cancer patients and decreased advanced stages of disease at diagnosis for rural breast cancer patients [

19,

20]. Increased screening and cancer detection, and decreased mortality were also observed for Stage II and III rectal cancer patients covered by Medicaid [

21].

Although Medicaid is historically for underserved populations; recent studies revealed disparities and gaps for cancer patients at “high-quality care” institutions [

22]. Limited numbers of participated institution, physician, and specialist are amongst many reasons as to why Medicaid coverage does not guarantee equal access to quality care and may lead to fragmented care, delayed care, inaccessibility to more costly therapeutics such as mAbs for cancer patients [

23,

24]. Such factors must be considered to understand the disparities in cancer survival for Medicaid patients [

25]. With the expanding Medicaid patient population, it is crucial to address the lack of universal and standardized care for cancer patients. The goal of this study is to examine whether insurance status (Medicaid versus Purchased) influences the usage of highly effective immunotherapeutics, specifically ramucirumab, for cancer patients using the All of Us (AoU) Database. Ramucirumab was selected for analysis in this study as it is a novel and expensive immunotherapy, proving to be effective in the treatment of several malignancies, but its accessibility to suitable cancer patients has not been thoroughly evaluated in previous literature. By analyzing the factors that influence insurance status, we hope to identify how socio-demographics play a role in impacting cancer patients’ access to quality clinical care and to raise attention to the inequities in the American healthcare system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Data was obtained from the AoU Research Program database which employs Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model Version 5 infrastructure to compile and standardize data from electronic health records (EHR) for researchers. Enrollment for AoU began in May 2018 and contains data for those ≥18 years old from more than 340 recruitment sites in the USA. Information was obtained from EHR, health questionnaires, physical measurements, the use of digital health technology such as Fitbit data, and the collection and analysis of biospecimens. With more than 175,000 participants, the variety of socioeconomic, lifestyle and biologic characteristics represents populations in the United States. Funded by the National Institute of Research (NIH), the AoU Research Program aims to deliver large and thorough datasets to advance medical research. The AoU data set consists of EHR data from various OMOP sources and data domains including Demographics, Conditions, Procedures, Drugs, Measurements, and Visits [

26].

2.2. Cohort Selection

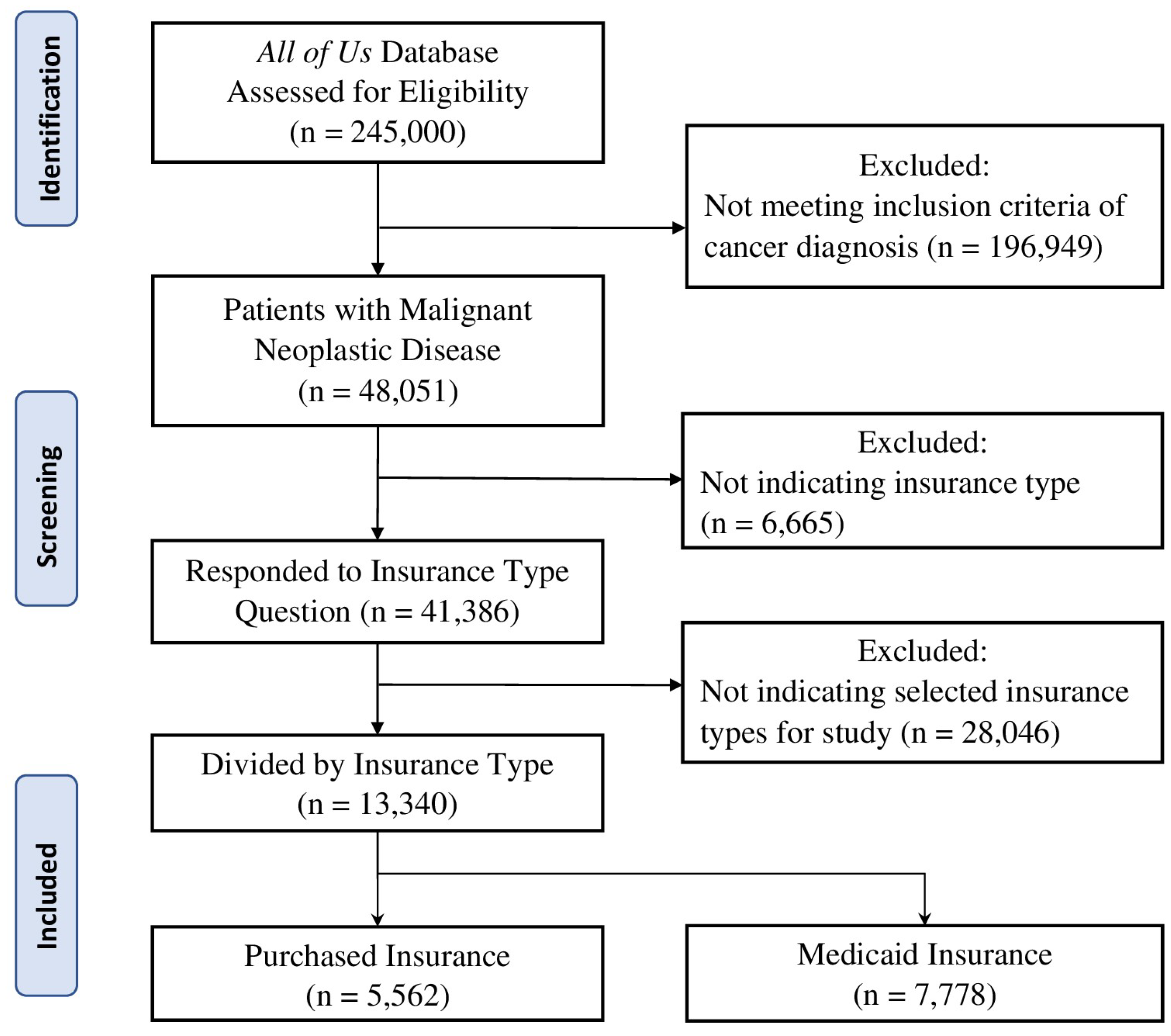

We used the AoU database to identify patients ≥18 years old, diagnosed with malignant neoplastic diseases, and indicated their insurance type as Purchased or Medicaid. Data were obtained from version 7 of the AoU Database which includes participant data from the start of enrollment in 5/2018 until 7/2022. Participant selection can be viewed in

Figure 1. Data for this project was extracted in June 2023. Of the 245,000 participants assessed for eligibility in the

All of Us database, 48,051 met criteria for diagnosis of malignant neoplastic disease. From this participant sample, 41,386 indicated their insurance type and 13,340 have the two insurances of interest for this study: 5,562 Purchased insurance holders and 7,778 Medicaid insurance holders. The screening and selection of participants for this study is conveyed in

Figure 1.

2.3. Outcomes Variables

Covariates analysis was focused on sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex at birth (Male, Female, or Not Answered), race (classified as Asian, Black/AA, White, None Indicated, or None of These), annual household income, and education attainment level. The term “Black/AA” was used for consistency with AoU database categorization. Patients were classified by insurance coverage type (Purchased or Medicaid). Finally, patients were categorized according to their use of ramucirumab, defined as the use of ramucirumab at any time of their clinical care.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic information was summarized using descriptive statistics. The Chi-square test of proportions was used to analyze the significance of patient cohort characteristics (age, sex at birth, race, annual household income, and education attainment level) between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups. We calculated proportions of ramucirumab users in Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups and used the Chi-square test of proportions to assess significance. Survey questions were employed to analyze the proportions of patients who indicated that their health insurance was not accepted by a healthcare provider or office, they could not afford seeing a specialist or primary care physician when needed, or they requested lower cost medications. Frequency comparison of patients in Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups was analyzed using two-proportion Z-tests to assess significance. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort Characteristics and Insurance Groups

We extracted data from 11339 patients with malignant neoplastic diseases either on Purchased (4676) or Medicaid (6663) insurance from the All of Us database. We observed a predominance of patients aged 65 years or older in the Purchased insurance group (84%) and a relatively equal distribution of 45-64 years old (45%) and 65+ years old (41%) patients in the Medicaid group. Compared to the Purchased group, the Medicaid group had a predominance of women: men of 2:1. We found that patients in the Purchased insurance group were more likely to identify as White race compared to the Medicaid insurance group (86% vs. 37%,

p < 0.0001). Patients in the Medicaid group were more likely to include African American race compared to the Purchased insurance group (28% vs. 5%,

p < 0.0001). Patients in the Medicaid insurance group specified their Annual Household Income predominantly in the <25K group compared to patients in the Purchased insurance group (53% vs 10%,

p < 0.0001). When comparing levels of Education Attainment, most patients (57%) in the Purchased insurance group described themselves having a College Graduate or Advanced Degree, while patients in the Medicaid insurance group were <12th grade (20%), 12th grade or GED (28%), and College (30%). Essentially, the Medicaid insurance group had a predominance of women, African American race, household income of <25K annually, and College or below education level in comparison to the Purchased insurance group (

Table 1).

3.2. Healthcare Access and Insurance Types

To assess the accessibility to healthcare for patients with malignant neoplastic diseases, we analyzed many relevant questions in the survey using Chi-squared test, thus the statistical significance between Purchased and Medicaid insurances can be revealed. Regarding general accessibility to healthcare services, there was statistical significance in proportion of patients whose health insurance was not accepted at a healthcare office (p < 0.0001), were unable to afford co-pay (p < 0.0001) and were unable to receive follow-up care due to not being able to afford it (p < 0.0001). No significance was found for patients having a high/unaffordable deductible (p = 0.299) and paying out of pocket for a procedure (p = 0.639). Survey questions pertaining to access to primary and specialist care showed a statistically significant difference between Purchased and Medicaid insurances for being unable to see a primary care physician (p < 0.0001) or a specialist (p < 0.0001) due to financial reasons in the past twelve months. No significance was found for having seen a primary care physician (p = 0.364) or a specialist (p = 0.066) in the past twelve months. Evaluation of access to therapeutics with ramucirumab showed statistical significance between Purchased and Medicaid proportions for skipping medication doses to save money (p < 0.0001), asking for a lower cost medication to save money (p < 0.0001), delaying filling a prescription to save money (p < 0.0001), and unable to get a prescription medication due to being unable to afford it (p < 0.0001). All these results were summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

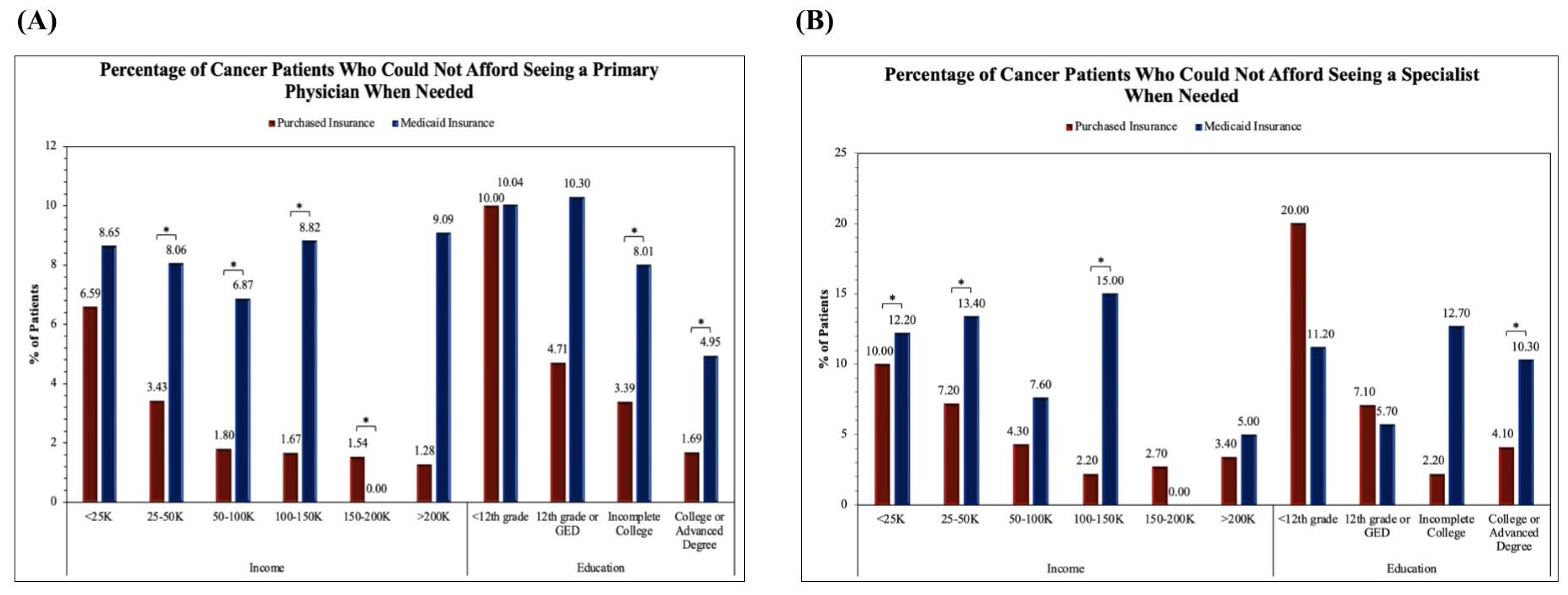

The upcoming figures (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) will further analyze prominent healthcare services by comparing service accessibility between Purchased and Medicaid insurances in relation to income and educational levels.

Figure 2A analyzes the proportion of cancer patients unable to see their primary care physician. The two proportion Z-test was applied to obtain results for comparing Purchased and Medicaid category frequencies. Significance between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups was found in the income levels of <25K (Z-score = -3.32, p = 0.00090), 25-50K (Z-score = -2.87, p = 0.0039), and 100-150K (Z-score = -4.05, p = 0.00005) in addition to the education level of College or Advanced Degree (Z-score = 3.51, p = 0.00044). The remainder of the income levels including 50-100K, 150-200K, and >200K and education levels <12th grade, 12th grade or GED, and Incomplete College were not found to have significant differences between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups.

Figure 2B analyzes the proportion of cancer patients unable to see a specialist. The two proportion Z-test was applied to obtain results for comparing Purchased and Medicaid category frequencies. Significance between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups was found in the income levels of 25-50K (Z-score = -2.88, p = 0.00403), 50-100K (Z-score = -3.46, p = 0.00053), 100-150K (Z-score = -2.73, p = 0.00636), and >200K (Z-score = -2.00, p = 0.04563) in addition to the education levels of Incomplete College (Z-score = -3.79, p = 0.00015) and College or Advanced Degree (Z-score = -4.34, p < 0.00001). The remainder of the income levels including <25K and 150-200K and education levels <12th grade and 12th grade or GED were not found to have significant differences between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups.

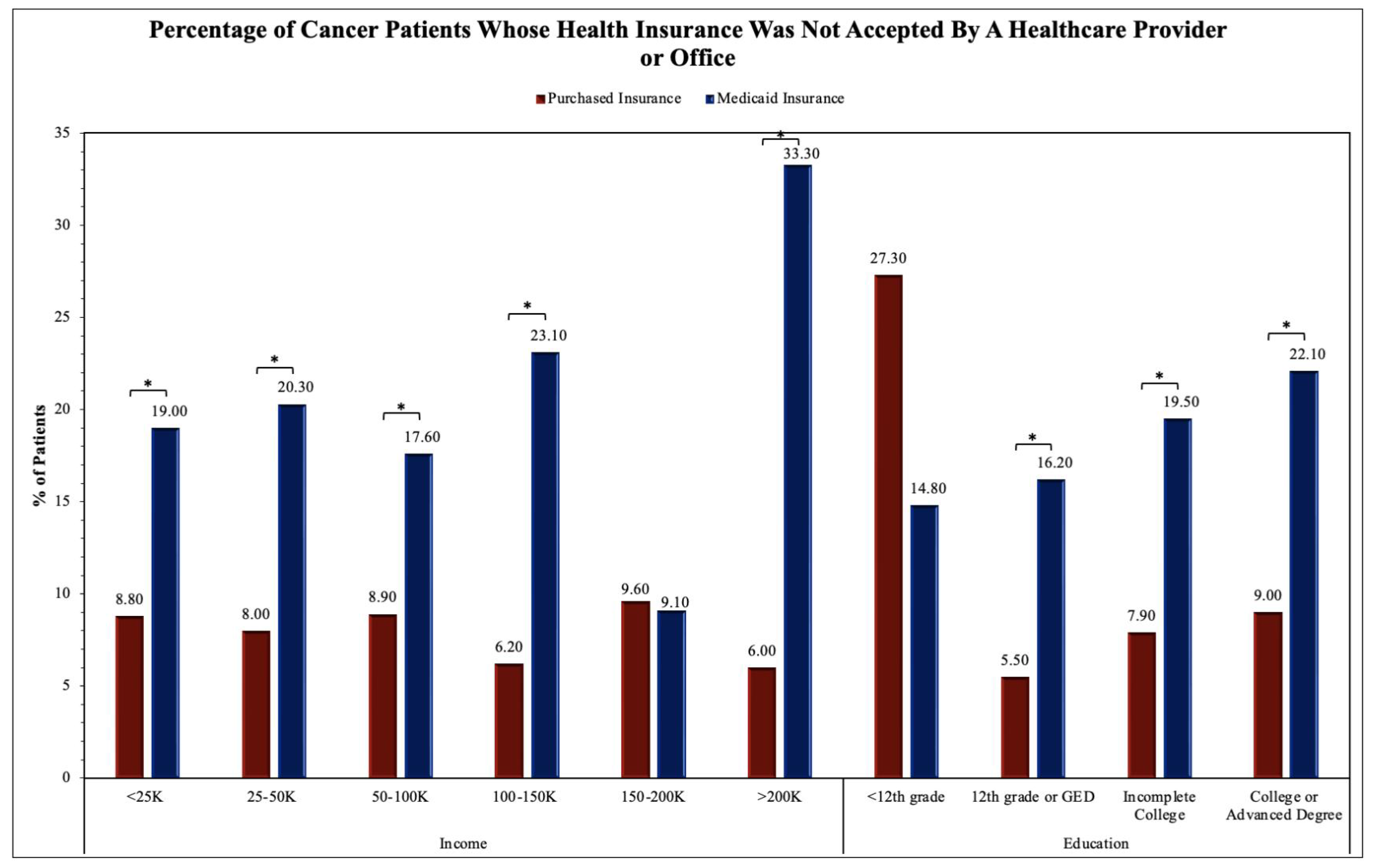

The two proportion Z-test was applied to obtain results for comparing Purchased and Medicaid category frequencies in

Figure 3. Significance between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups was found in the income levels of 50-100K (Z-score = 2.53, p = 0.01151) and >200K (Z-score = -3.24, p = 0.00121). The remainder of the income levels including <25K, 25-50K, 100-150K, and 150-200K and all education levels including <12th grade, 12th grade or GED, Incomplete College, and College or Advanced Degree were not found to have significant differences between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups.

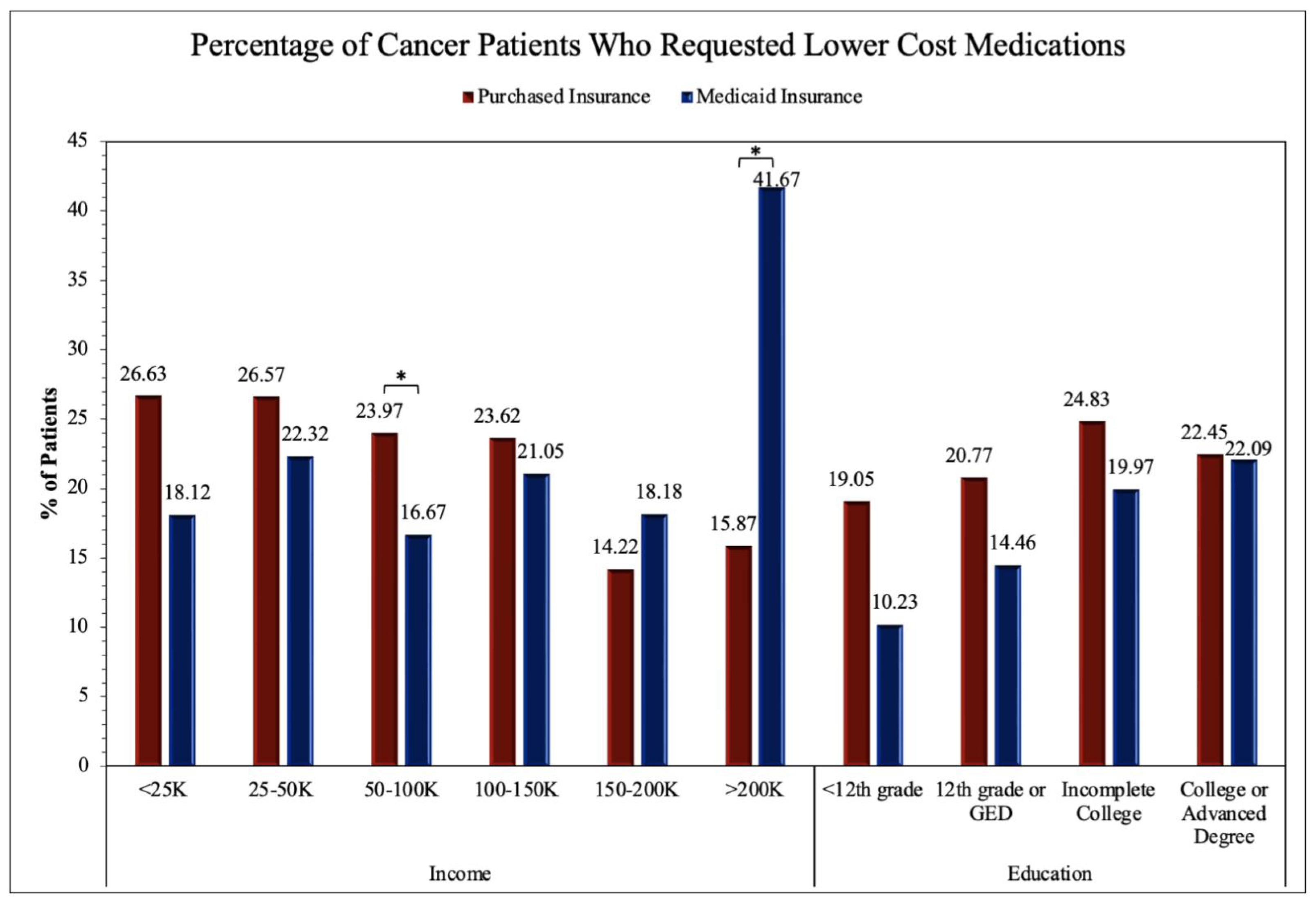

The two proportion Z-test was applied to obtain results for comparing Purchased and Medicaid category frequencies in

Figure 4. Significance between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups was found in the income levels of <25K (Z-score = -3.73, p = 0.00019), 25-50K (Z-score = -5.49, p < 0.00001), 50-100K (Z-score = -3.29, p = 0.00099), 100-150K (Z-score = -3.88, p = 0.00010), and >200K (Z-score = -3.60, p = 0.00031) in addition to the education levels of 12th grade or GED (Z-score = -4.65, p = 0.00001), Incomplete College (Z-score = -6.82, p < 0.00001), and College or Advanced Degree (Z-score = -8.88, p < 0.00001). The remaining income levels of 150-200K and education levels of <12th grade were not found to have significant differences between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups.

3.3. Ramucirumab Usage and Insurance Types

As identified in this paper, socioeconomic (SES) factors determine the type of insurance a patient holds. When comparing these diverse types of insurances, there are evident differences in accessibility to diagnostic, therapeutic, and follow-up care that influence long-term outcomes. The late overall survival (LOS) in young cancer patients was significantly longer in those with Purchased insurances compared to public insurances [

16]. Rates of enrollment in clinical trials for cancer treatment were found to be disproportionate amongst the different insurance holders, suggesting disparities in access to treatment resources [

17]. A meta-analysis found that those with Medicaid insurance and uninsured patients were more likely to be diagnosed in late stages (stage III/IV) of cancer and had worse short-term and long-term survival compared to those with Purchased insurance [

27].

Since cancer outcomes vary widely based on insurance types, it is likely that differences in accessibility to cancer screening tools, therapeutic resources, and regression management are the sources of these variations. Due to new and expensive therapies in the treatment of cancer and rising population numbers, oncologic expenditures are a large concern to health cost burdens on patients and insurance companies. We direct our attention to discrepancies in access to monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), a specialized targeted therapy that offers a promising treatment for cancer patients. However, mAbs are also expensive to manufacture and distribute. The complex protein structure of mAbs requires precise design, development, and manufacturing with downstream processing for impurities and other quality assurances [

28]. Due to this intricate process, production of mAbs is more costly compared to chemotherapeutics, presenting a higher treatment cost to patients and health insurance companies [

29]. This may explain why cancer patients with certain insurances are less likely to receive and be treated with mAbs compared to their insurance counterparts. To demonstrate the differences in mAb accessibility across different insurances, comparisons were analyzed in Ramucirumab usage in

Table 3 and

Figure 5.

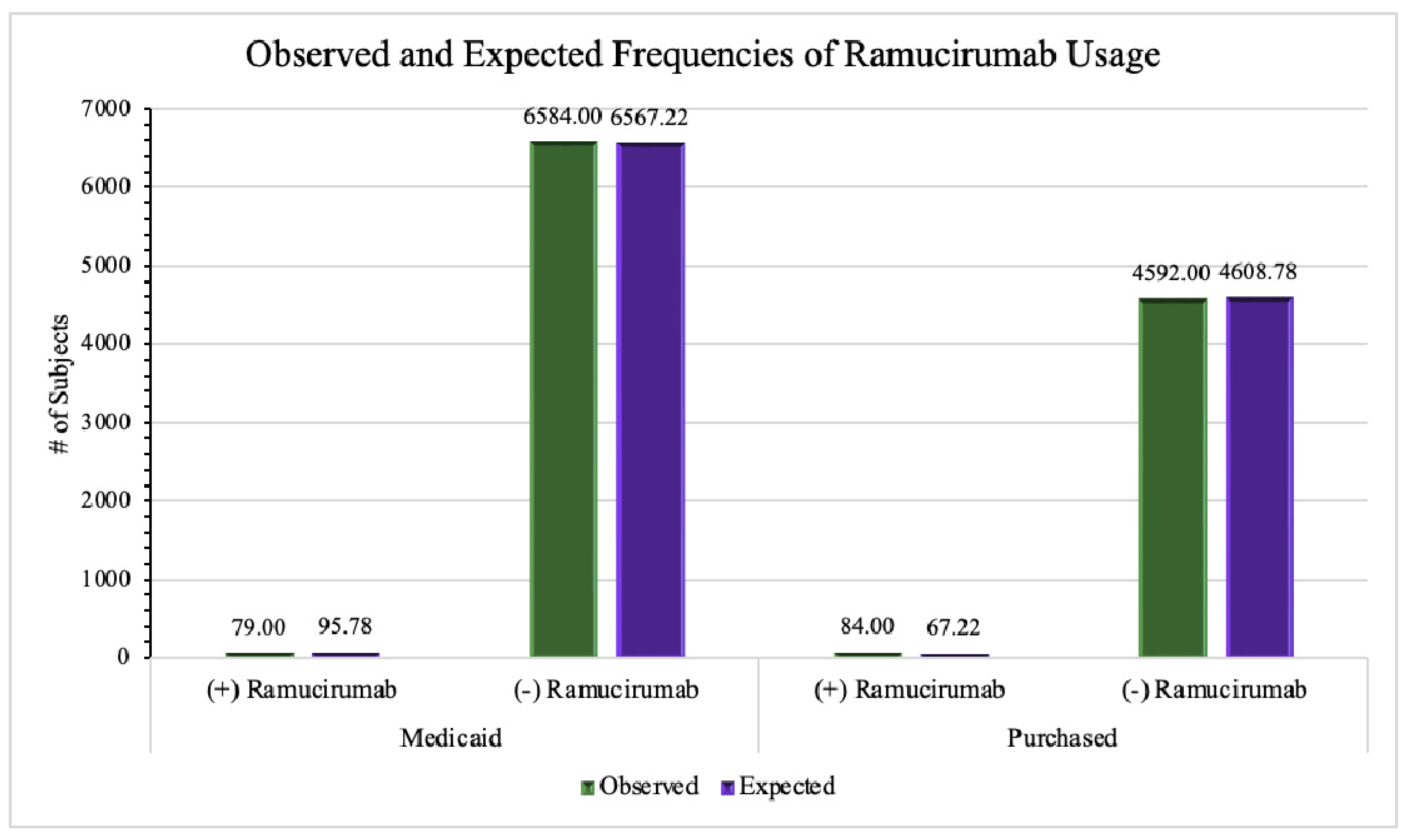

To determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between Purchased and Medicaid insurances regarding the use of ramucirumab to treat various cancers, we extracted information from the 5562 patients with malignant neoplastic diseases with Purchased insurance, 92 (1.65%) patients used ramucirumab to treat their condition and 5470 patients (98.3%) did not. According to the AoU Database, out of the 7778 cancer patients covered by Medicaid insurance holders, 85 (1.09%) of patients used ramucirumab and the remaining 7693 (98.9%) did not. We found that the difference between ramucirumab usage and insurance type was statistically significant (p = .005) (

Table 3). While the difference between the two frequencies (1.65% and 1.09%) appears minimal, the relatively large sample size ensures the reliability of results with statistical significance. The observed and expected frequencies of ramucirumab use are displayed in

Figure 5.

Ramucirumab is an emerging therapeutic that offers a specialized treatment for cancers to improve progression-free and overall survival times. One study concluded that ramucirumab used in conjunction with paclitaxel significantly increased overall survival in 330 patients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma compared to the 335 patients in the placebo group [

11]. The mAb also significantly improved progression-free survival and overall survival for HCC patients, however it is important to note that there was also an increase in adverse effects (e.g., hemorrhage events, liver injury, proteinuria, etc.) [

12]. A phase III trial on metastatic NSCLC also produced comparable results; when added to erlotinib treatment, ramucirumab was shown to increase progression-free survival for patients [

13]. Similar conclusions on overall survival were also found in a phase II trial for 130 patients with advanced NSCLC [

14]. Although several studies indicated an increase in adverse events with ramucirumab usage [

12], the associated adverse effects and toxicities of ramucirumab were manageable. Moreover, the increased progression-free and overall survival times takes precedence.

Despite its high efficacy in the treatment of cancer patients, ramucirumab use varies significantly between Purchased and Medicaid insurances. The reasons behind this difference are more likely due to SES factors. Health economic factors are critical when considering the inclusion of monoclonal antibodies to treatment of cancers, which are measured using criteria referred to as cost-effectiveness (CE). CE analyzes the effectiveness of a medication regarding cost by considering several therapeutic outcomes. These include the probability of progression-free states, rates of toxicity/adverse effects and their management costs, and long-term clinical outcomes such as overall survival rates [

30]. With the cost of cancer care in the United States (US) likely surpassing

$175 billion, there has been a shift in increased value in cost-effectiveness. Due to their high production costs, several mAbs have high-cost thresholds that require greater improvement in toxicity and survival compared to other chemotherapeutics. Economic evaluations of ramucirumab demonstrate the limited cost-effectiveness that this medication can offer [

12,

31,

32]. Considering the high market cost of ramucirumab; it is noted that lowering the cost of production would likely adjust the cost-effectiveness and offer more Medicaid patients the option to use ramucirumab, with the hope to improve survival rates.

4. Discussion

In our analysis, we identified multiple SES factors associated with differences in insurance types. Younger (<64 years old) and female patients were more likely than older (65+ years old) and male patients to have Medicaid insurance. We observed that White patients were more likely than Black/AA patients to have Purchased insurance. Overall, patients with lower household incomes and levels of education attainment were more likely to have Medicaid insurance than Purchased insurance. Rates of ramucirumab use in patients with malignant neoplastic disease are compared between Medicaid and Purchased insurances to assess for discrepancies in their therapeutic use, which is consequently associated with prognosis and quality of life. As prognosis and outcomes for malignant conditions vary widely between insurance types, it can be assumed that those who are Black/AA, have a lower SES status, or have lower educational attainment are less likely to use ramucirumab, other mAbs, and more costly therapeutics as part of their fight against cancers. Our analysis contributes to the case in which cancer patients who are traditionally not hindered by the social determinants of health are able to afford Purchased insurances, benefit from the resources and options, and subsequently have better outcomes for their respective cancers.

Survey questionnaire responses by Purchased and Medicaid insurance holders helped establish the difference in accessibility of healthcare services. Highly related survey questions were chosen and analyzed by annual household incomes and educational levels. We found that fundamental healthcare services such as seeing a primary care physician (

Figure 2A) and insurance acceptance (

Figure 3) demonstrated significant differences between Purchased and Medicaid insurances compared to specialized healthcare services such as seeing a specialist (

Figure 2B) or requesting lower cost medication (

Figure 4). However, it is important to address that several income and education levels throughout the four survey questions (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) do not demonstrate the same statistically significant difference, indicating variability of accessibility within both Purchased and Medicaid insurances. As cancer is a high-mortality and morbidity disease, patients have access to specialist care and standard chemotherapeutics regardless of insurance type or SES status which may explain the results seen in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 [

33].

The results of our study are consistent with previous literature as historically, African American and other minority groups have lower rates of private insurance compared to their White counterparts [

34]. Inadequate healthcare insurance has been shown to impact cancer patient survival. Previous literature has also established that African American patients have the lowest survival rate and highest mortality of any racial group for most cancers, including colorectal cancer [

35] and HCC [

36,

37]. One study reported uninsured African American patients with metastatic colorectal cancer had lower rates of receipt of chemotherapy and higher mortality rates compared with White patients and those with private insurance [

38]. Moreover, a 2020 retrospective study demonstrated how Medicaid and uninsured cancer patients did not receive additional survival benefits from experimental therapies compared with their private insurance counterparts [

39]. This coincides with the results of this study as those with Medicaid insurance (i.e., Black/AA, lower SES status, lower educational level) are less likely to receive ramucirumab therapy. As an individual’s health care insurance is largely determined by their SES, it is safe to say that an individual’s SES can dictate the quality of healthcare one receives.

Although insurance plays a significant role in the quality and accessibility of medical services, it is also important to address the institutional, societal, racial, and cultural factors that contribute to the healthcare discrepancies in the United States. Despite the 2010 Affordable Care Act best efforts in extending health insurance coverage to many more qualifying American citizens, it is still insufficient in combating the health inequities and disparities faced by underserved communities [

40]. Moreover, Hao et al. showcased that regardless of insurance type, African American and Hispanic patients are still less likely to receive standard care for cancer [

41]. Barriers to receiving and accepting standard cancer care may extend beyond insurance type, including medical mistrust, fatalism and negative surgical beliefs amongst African American patients [

42,

43].

Although patient access to a primary care physician or healthcare provider is multifactorial, our study demonstrates restrictions Medicaid cancer patients face despite being insured. Such restrictions are also evident with medication usage as more cancer patients with Purchased insurance are more likely to use the costly ramucirumab for treatment compared to their Medicaid counterparts (

Table 2). Our study primarily focuses on the discrepancies of ramucirumab access, however there may be additional targeted and immunotherapies that are also less accessible to Medicaid patients. Although there was a statistically significant difference between Purchased and Medicaid insurances for ramucirumab usage, this does not reflect the discrepancies between different types of Purchased insurance. Purchased insurance encompasses any private health insurance companies, each with individualized guidelines, policies, and resources. For this reason, future research should be directed to analyzing each insurance program independently rather than grouping them together that may misrepresent and generalize findings to all Purchased insurance companies. Overall, our study revealed how societal and economic categories have overarching consequences related to healthcare, provider, and therapeutic access that may drastically impact a cancer patient’s prognosis and survival likelihood.

One of the limitations of our study is that our data was limited to the AoU Database which contains missing data that could further shed light on the differences between insurance groups. Information regarding cancer-free states, survival, and overall prognosis was missing from the available data, preventing insight into the effectiveness of ramucirumab and if ramucirumab can improve mortality burden. Another limitation is regarding the use of ramucirumab for specific neoplasms. The patients in Purchased and Medicaid insurances may not be equally proportionate in the types of cancer diagnoses, therefore, this would contribute to varied uses of ramucirumab according to cancer type. As ramucirumab is only FDA-approved to treat metastatic colorectal cancer, HCC, NSCLC, and gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma, it may be worth investigating if there are similar trends or discrepancies with these cancer types.

5. Conclusions

This study utilizes the very broad All of Us Database to examine the social determinants of health faced by cancer patients, how those factors are correlated with insurance types and healthcare access, and how insurance can dictate patients’ immunotherapeutic access/usage such as ramucirumab. Our results identified the persistent socioeconomic and racial disparities in the American healthcare system exemplified by the ramucirumab use between Purchased and Medicaid insurance groups.

By highlighting the shortcomings and inequities of the American health system, we hope that improvements in these areas can be made, and future health policies can be implemented to not limit patients’ healthcare access based on their SES, race, or education level. As cancer is a life-threatening disease with very limited therapeutic options, it is crucial for every cancer patient to receive equal, prompt, and high- quality care in order to improve the overall disease outcomes.

Author Contributions

ST and VT conceived this study; JL guided the study design, data analysis, and result interpretation; ST and VT wrote the manuscript; JL, ST, and VT revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the intramural research funds of California University of Science and Medicine to Dr. Ling.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved and reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of California University of Science and Medicine on July 13, 2023 (Protocol Application#: HS-2023-39).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not necessary for this study as patients’ identifiable information was not used. All of Us has informed consent for all participants during their data collection stage, and we follow All of Us policy for using their data in research.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are available as a featured workspace to registered researchers of the

All of Us Researcher Workbench. For information about access, please visit

https://www.researchallofus.org/.

Acknowledgments

The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers (1 OT2 OD026549, 1 OT2 OD026554, 1 OT2 OD026557, 1 OT2 OD026556, 1 OT2 OD026550, 1 OT2 OD 026552, 1 OT2 OD026553, 1 OT2 OD026548, 1 OT2 OD026551, 1 OT2 OD026555 and IAA: AOD 16037), Federally Qualified Health Centers (HHSN 263201600085U), Data and Research Center (5 U2C OD023196), Biobank (1 U24 OD023121), The Participant Center: (U24 OD023176), Participant Technology Systems Center (1 U24 OD023163), Communications and Engagement (3 OT2 OD023205 and 3 OT2 OD023206) and Community Partners (1 OT2 OD025277, 3 OT2 OD025315, 1 OT2 OD025337 and 1 OT2 OD025276). In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest involved in this study.

References

- Xu, J.Q.; Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief 2022, 456, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Risk of Dying from Cancer Continues to Drop at an Accelerated Pace. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/facts-and-figures-2022.html (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Anand, U.; Dey, A.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Sanyal, R.; Mishra, A.; Pandey, D.K.; De Falco, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Chaudhary, A.; et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, A; Kalyani, C.V.; Rohilla, K.K. Incidence and severity of self-reported chemotherapy side-effects in patients with hematolymphoid malignancies: A cross-sectional study. Cancer Res Stat Treat 2020, 3, 736-741. [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P.M.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Blinder, V.S. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: Understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Acevedo, A.; Davidoff, E.J.; Timmins, L.M.; Marrero-Berrios, I.; Patel, M.; White, C.; Lowe, C.; Sherba, J.J.; Hartmanshenn, C.; et al. The growing role of precision and personalized medicine for cancer treatment. Technology Singap World Sci 2018, 6, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bove, A.M.; Simone, G.; Ma, B. Molecular Bases of VEGFR-2-Mediated Physiological Function and Pathological Role. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 599281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Ramucirumab. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/ramucirumab (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Wilke, H.; Muro, K.; Van Cutsem, E.; Oh, S.C.; Bodoky, G.; Shimada, Y.; Hironaka, S.; Sugimoto, N.; Lipatov, O.; Kim, T.Y.; et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014, 15, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Qin, Z.; Qiu, X.; Zhan, M.; Wen, F.; Xu, T. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ramucirumab treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib with alpha-fetoprotein concentrations of at least 400 ng/ml. J Med Econ 2020, 23, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Garon, E.B.; Seto, T.; Nishio, M.; Ponce Aix, S.; Paz-Ares, L.; Chiu, C.H.; Park, K.; Novello, S.; Nadal, E.; et al. Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated, EGFR-mutated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (RELAY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckamp, K.L.; Redman, M.W.; Dragnev, K.H.; Minichiello, K.; Villaruz, L.C.; Faller, B.; Al Baghdadi, T.; Hines, S.; Everhart, L.; Highleyman, L.; et al. Phase II Randomized Study of Ramucirumab and Pembrolizumab Versus Standard of Care in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Previously Treated With Immunotherapy-Lung-MAP S1800A. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid, children’s health insurance program, & basic health program eligibility levels. Available online: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-childrens-health-insurance-program-basic-health-program-eligibility-levels/index.html (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Cuglievan, B.; Berkman, A.; Dibaj, S.; Wang, J.; Andersen, C.R.; Livingston, J.A.; Gill, J.; Bleyer, A.; Roth, M. Impact of Lagtime, Health Insurance Type, and Income Status at Diagnosis on the Long-Term Survival of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2021, 10, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullenger, R.D.; Deal, A.M.; Grilley Olson, J.E.; Matson, M.; Swift, C.; Lux, L.; Smitherman, A.B. Health Insurance Payer Type and Ethnicity Are Associated with Cancer Clinical Trial Enrollment Among Adolescents and Young Adults. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2022, 11, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HealthCare. Medicaid & CHIP coverage. Available online: https://www.healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Lei, X.; Malinowski, C.; Zhao, H.; Shih, Y.C.; Giordano, S.H. Medicaid expansion, chemotherapy delays, and racial disparities among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2023, 115, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, A.I.; Li, T.; Yu, Q.; Wu, X.C.; Yi, Y.; Hsieh, M.C.; Havron, W.; Shoup, M.; Chu, Q.D. Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Southern States. J Am Coll Surg 2023, 236, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; O’Guinn, M.; Zipprer, E.; Hsieh, J.C.; Dardon, A.T.; Raman, S.; Foglia, C.M.; Chao, S.Y. Impact of Medicaid Expansion on the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes of Stage II and III Rectal Cancer Patients. J Am Coll Surg 2022, 234, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, V.A.; Hsiang, W.R.; Nie, J.; Demkowicz, P.; Umer, W.; Haleem, A.; Galal, B.; Pak, I.; Kim, D.; Salazar, M.C.; et al. Acceptance of Simulated Adult Patients With Medicaid Insurance Seeking Care in a Cancer Hospital for a New Cancer Diagnosis. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2222214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Cheng, M.; Zhuang, S.; Qiu, Z. Impact of Insurance Status on Stage, Treatment, and Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis. Med Sci Monit 2019, 25, 2397–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, J.S.; Bauer, P.S.; Barron, J.; Bommireddy, A.; Chapman, W.C., Jr.; Schad, C.; Ohman, K.; Hunt, S.; Mutch, M.; Silviera, M. Fragmented Care in the Treatment of Rectal Cancer and Time to Definitive Therapy. J Am Coll Surg 2021, 232, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, J.H.; Rosenbaum, P.R.; Ross, R.N.; Reiter, J.G.; Niknam, B.A.; Hill, A.S.; Bongiorno, D.M.; Shah, S.A.; Hochman, L.L.; Even-Shoshan, O.; et al. Disparities in Breast Cancer Survival by Socioeconomic Status Despite Medicare and Medicaid Insurance. Milbank Q 2018, 96, 706–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 668–676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Nogueira, L.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jemal, A.; Halpern, M.T.; Yabroff, K.R. Health insurance status and cancer stage at diagnosis and survival in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2022, 72, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matte, A. Recent Advances and Future Directions in Downstream Processing of Therapeutic Antibodies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J; Kalaitzandonakes, N. The economic potential of plant-made pharmaceuticals in the manufacture of biologic pharmaceuticals. J. Commer Biotechnol 2011, 17, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Sprave, T.; Haque, W.; Simone, C.B., 2nd; Chang, J.Y.; Welsh, J.W.; Thomas, C.R., Jr. A systematic review of the cost and cost-effectiveness studies of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 2018, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, X.; Peng, L.; Yi, L.; Wan, X.; Zeng, X.; Tan, C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adding ramucirumab to the first-line erlotinib treatment for untreated EGFR-mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in China. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Peng, L.; Tan, C.; Zeng, X.; Wan, X.; Luo, X.; Yi, L.; Li, J. Cost-Effectiveness of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel as a second-line therapy for advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal cancer in China. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicare. Chemotherapy. Available online: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/chemotherapy (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Census. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2018. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-267.html (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Earl, V.; Beasley, D.; Ye, C.; Halpin, S.N.; Gauthreaux, N.; Escoffery, C.; Chawla, S. Barriers and Facilitators to Colorectal Cancer Screening in African-American Men. Dig Dis Sci 2022, 67, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, L.A.; Hinton, A.; Conteh, L.F. African Americans are less likely to receive curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2018, 10, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Miller, K.D.; Tossas, K.Y.; Winn, R.A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022, 72, 202–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakos, A.T.; Irish, W.; Parikh, A.A.; Snyder, R.A. The association of health insurance and race with treatment and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.M.; Blanke, C.D.; LeBlanc, M.; Barlow, W.E.; Vaidya, R.; Ramsey, S.D.; Hershman, D.L. Association of Patient Demographic Characteristics and Insurance Status With Survival in Cancer Randomized Clinical Trials With Positive Findings. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e203842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.; Pawlik, T.M. Insurance status and high-volume surgical cancer: Access to high-quality cancer care. Cancer 2021, 127, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Snyder, R.A.; Irish, W.; Parikh, A.A. Association of race and health insurance in treatment disparities of colon cancer: A retrospective analysis utilizing a national population database in the United States. PLoS Med 2021, 18, e1003842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, C.R.; Rogers, T.N.; Matthews, P.; Le Duc, N.; Zickmund, S.; Powell, W.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; McKoy, A.; Davis, F.A.; Okuyemi, K.; et al. Psychosocial determinants of colorectal Cancer screening uptake among African-American men: understanding the role of masculine role norms, medical mistrust, and normative support. Ethn Health 2022, 27, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.J.; Mhango, G.; Wall, M.M.; Lurslurchachai, L.; Bond, K.T.; Nelson, J.E.; Berman, A.R.; Salazar-Schicchi, J.; Powell, C.; Keller, S.M.; et al. Cultural factors associated with racial disparities in lung cancer care. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014, 11, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).