Submitted:

18 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| Essential elements | References | Non-essential elements | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(I) | 38, 41- 44 | Ni(II) | 77, 79, 80 |

| Cu(II) | 36, 45-50 | Pd(II) | 51, 82, 83, 84 |

| Zn(II) | 29, 34, 35, 59-65 | Pt(II) | 84 |

| Co(II) and Co(III) | 30, 31, 66-70 | Ag(I) | 52, 85 |

| Fe(II) and Fe(III) | 32, 33, 71-75 | Ga(III) | 68, 81 |

| La(III), Eu(III), Tb(III) | 87 | ||

| Technique | Donor atom | Metal | Structure | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D 1H and 2D 1H−1H TOCSY NMR | S | Cu(I) | 38 | |

| COSY, TOCSY and NOESY, or ROESY | S | Cu(I) | 42 | |

| X-ray crystallography, elemental analysis, UV-Vis, 1H-, 13C-NMR, LC/MS | N, S | Cu(II) | 36 | |

| 1D 1H and 2D 1H−1H TOCSY and NOESY, HMQC, HSQC, 1H-15N 2D NMR | S | Cu(II) | 45 | |

| UV-Vis, ESI-MS, EPR, COSY, ROESY and TOCSY NMR | O, N | Cu(II) | square-planar or square-pyramidal geometries | 46 |

| UV-Vis, CD, ESR, NMR spectroscopic and MS methods | N | Cu(II) | 48 | |

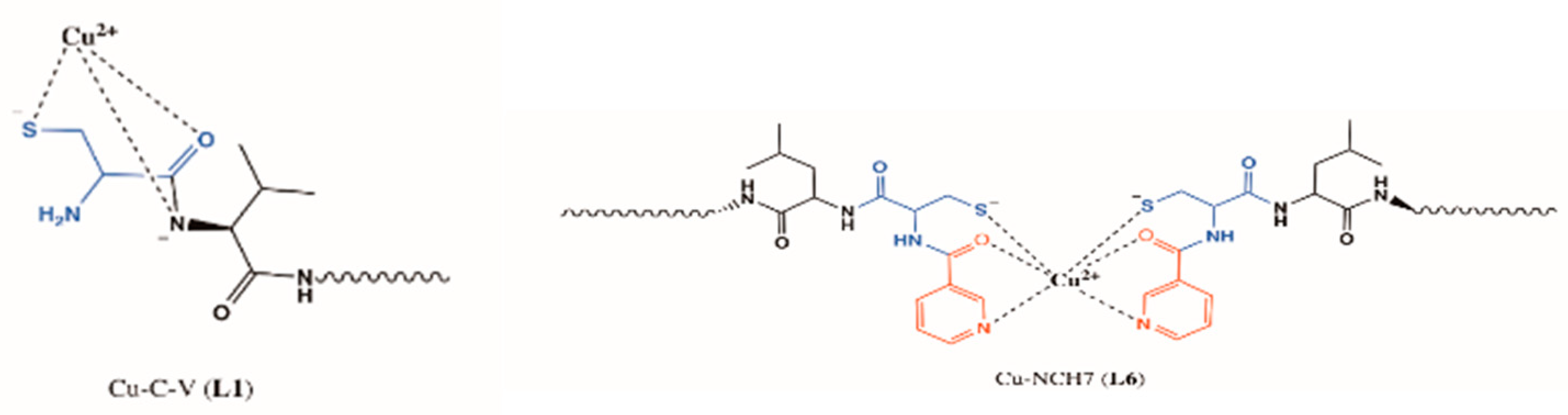

| voltammetric (cyclic) and spectral (UV-Vis and fluorimetric) analytical techniques, IR, EPR | O, N, S for L1, L3, L6 and O, N for L2, L4 | Cu(II) | 50 | |

| UV-Vis, EPR, 1H–1H TOCSY, 1H–13C HSQC | N, O | Co(II) and Mn(II) | octahedral | 69 |

| 1H NMR, 1H-1H TOCSY | N, O | Co(III) | 67 | |

| 1D 1H and 2D NMR, CD and computational methods | N | Fe(II) and Co(II) | 73 | |

| UV-Vis, 1D 1H NMR spectra or 2D soft-COSY experiments | S | Zn(II) | 63 | |

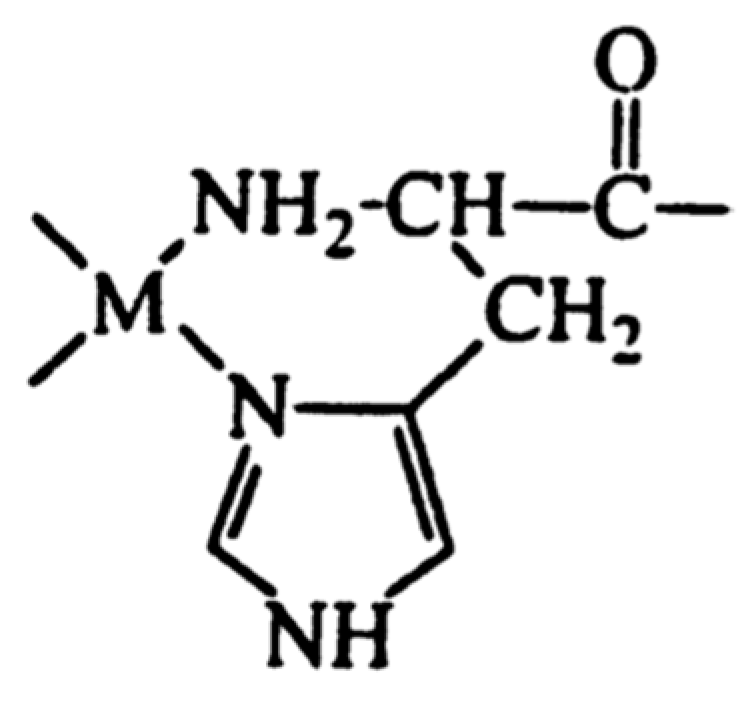

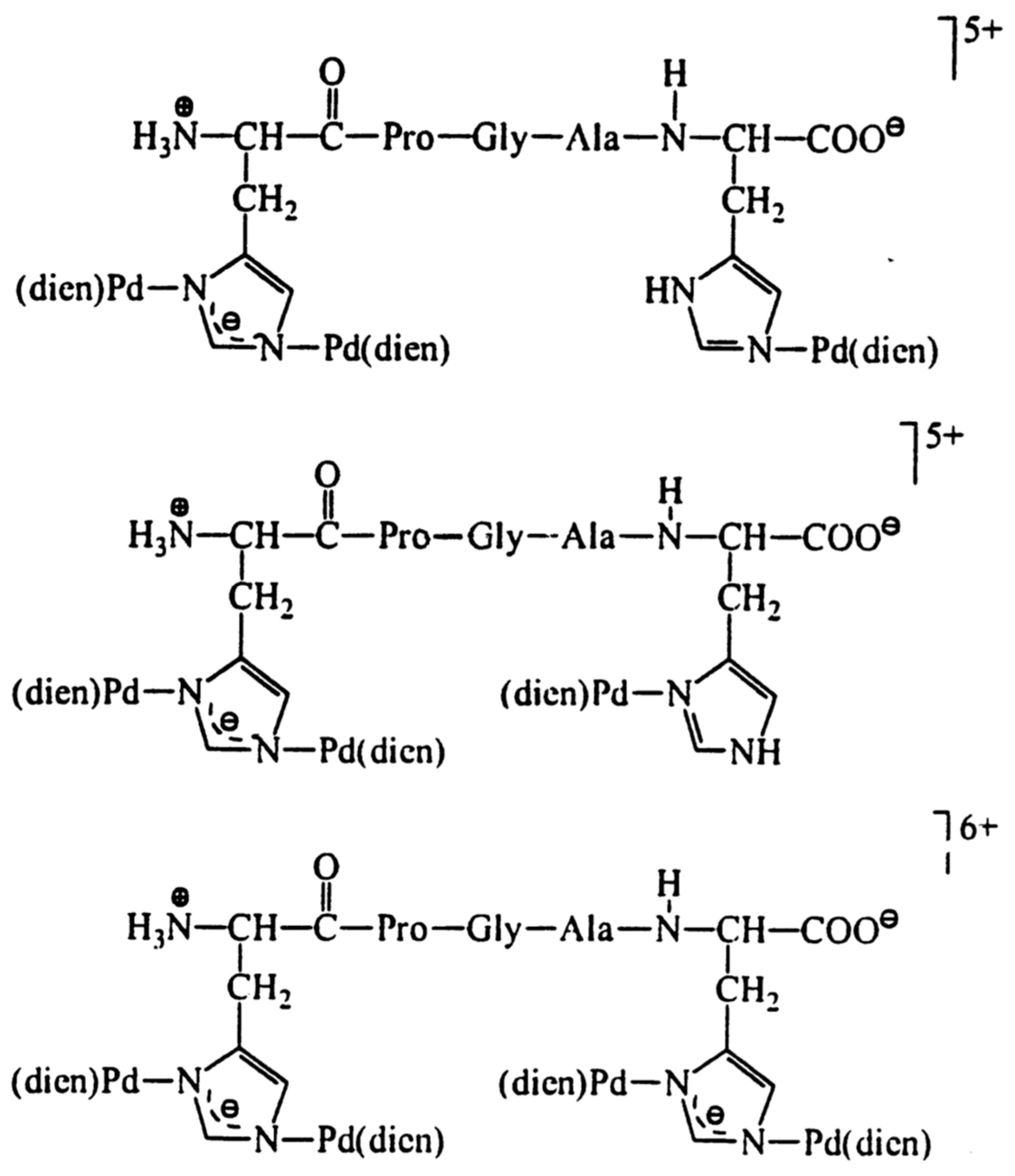

| ESI-MS, TOCSY, NOESY, ROESY, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-15N HSQC NMR | N | Pd(II) | square-planar | 51 |

| ESI–MS, TOCSY and ROESY, 1H-15N HSQC NMR | N | Al(III) | 76 | |

| UV-Vis, CD, ROESY, TOCSY, NOESY NMR | N | Ni(II) and Cu(II) | square-planar | 77 |

| 1H-, 13C- and 195Pt-NMR | N | Pd(II) | square-planar | 84 |

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

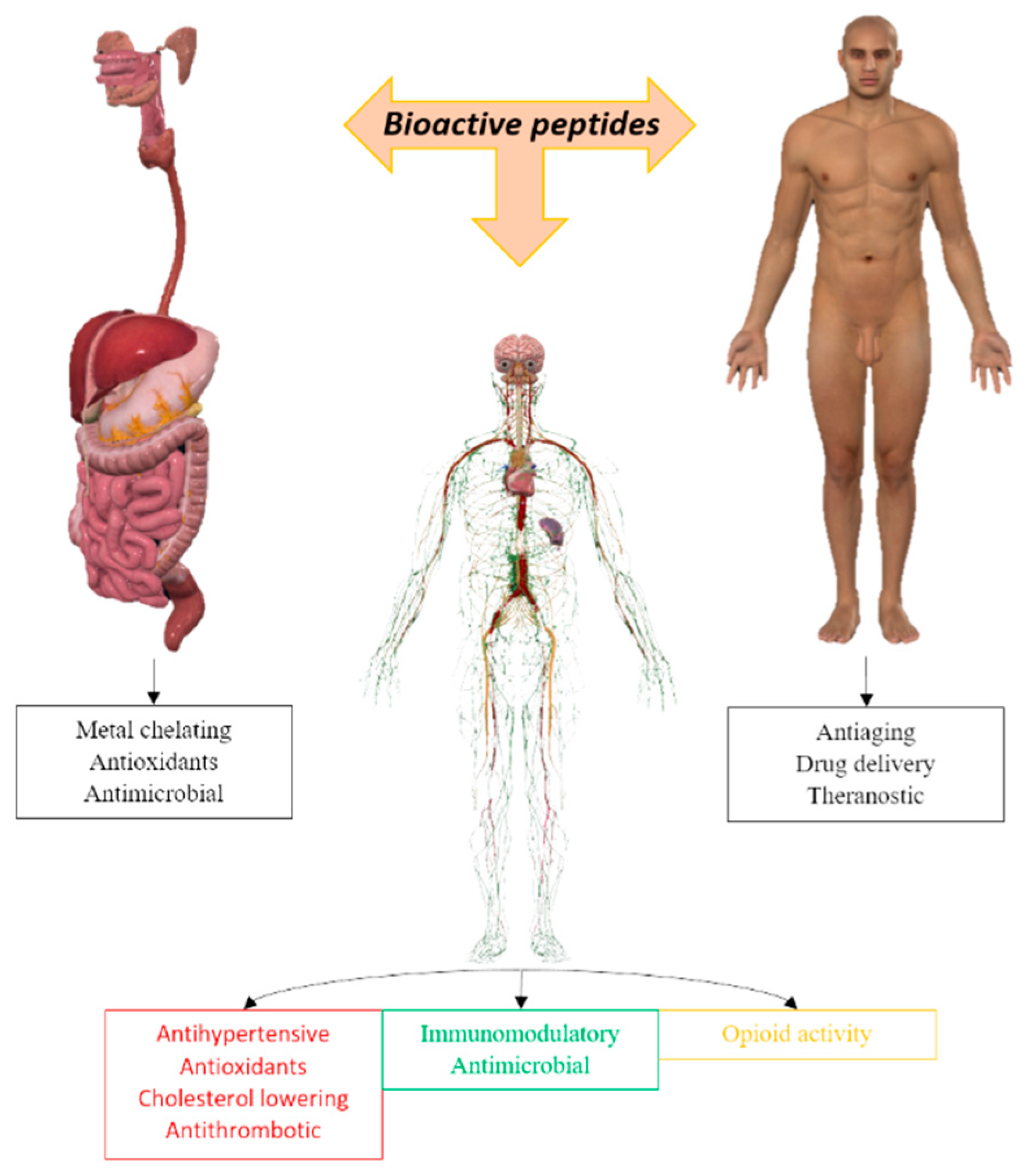

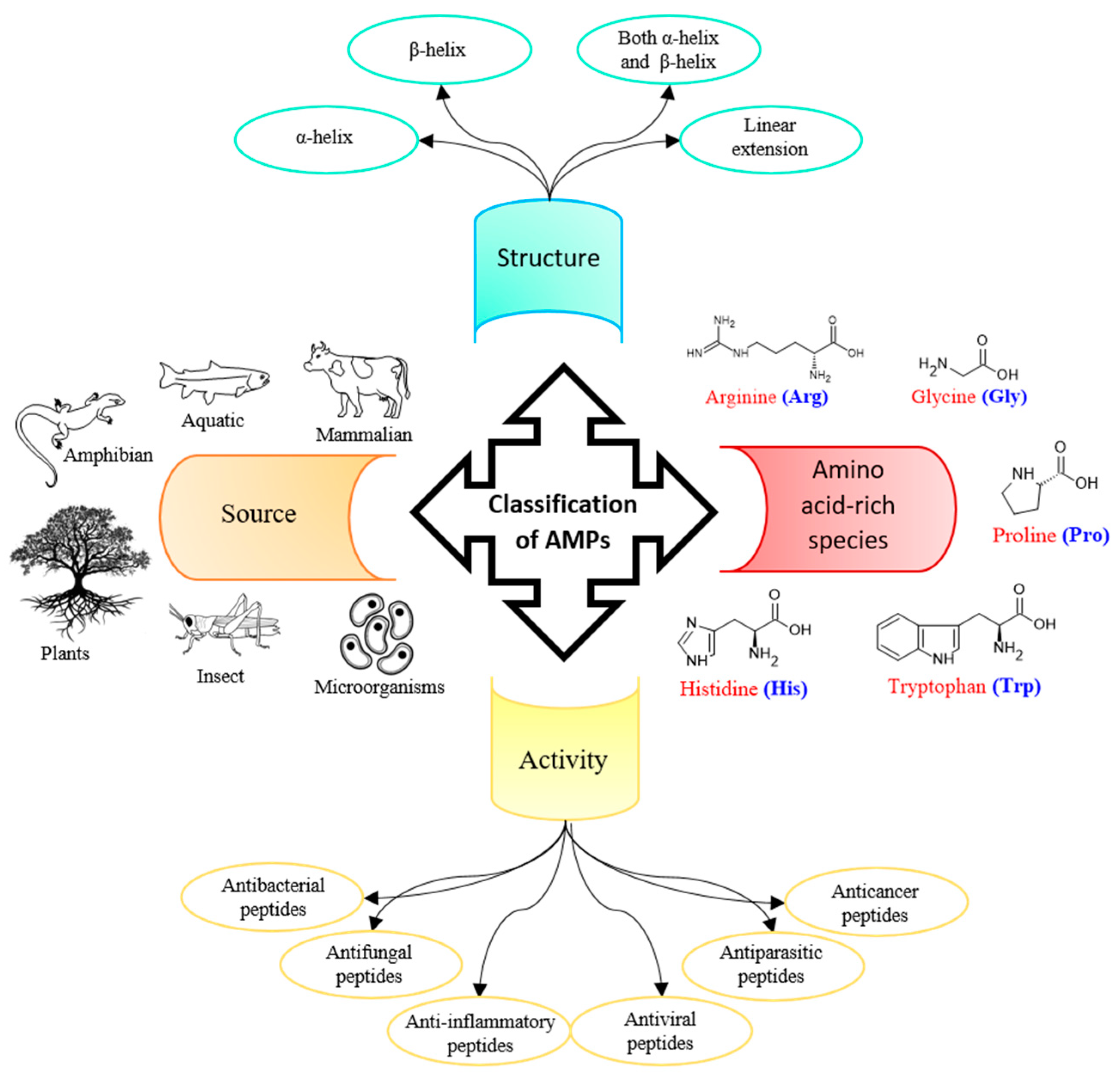

- Akbarian, M.; Khani, A.; Eghbalpour, S.; Uversky, V.N. Bioactive Peptides: Synthesis, Sources, Applications, and Proposed Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.L.; Dunn, M.K. Therapeutic Peptides: Historical Perspectives, Current Development Trends, and Future Directions. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y. Anti-Cancer Peptides: Classification, Mechanism of Action, Reconstruction and Modification. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Zhao, D.; Li, L.; Cheng, Z.; Guo, Y. Antiviral Peptides with in Vivo Activity: Development and Modes of Action. Chem Plus Chem 2021, 86, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, M.H.; Ahmad, K.; Saeed, M.; Alharbi, A.M.; Barreto, G.E.; Ashraf, G.M.; Choi, I. Peptide Based Therapeutics and Their Use for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative and Other Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

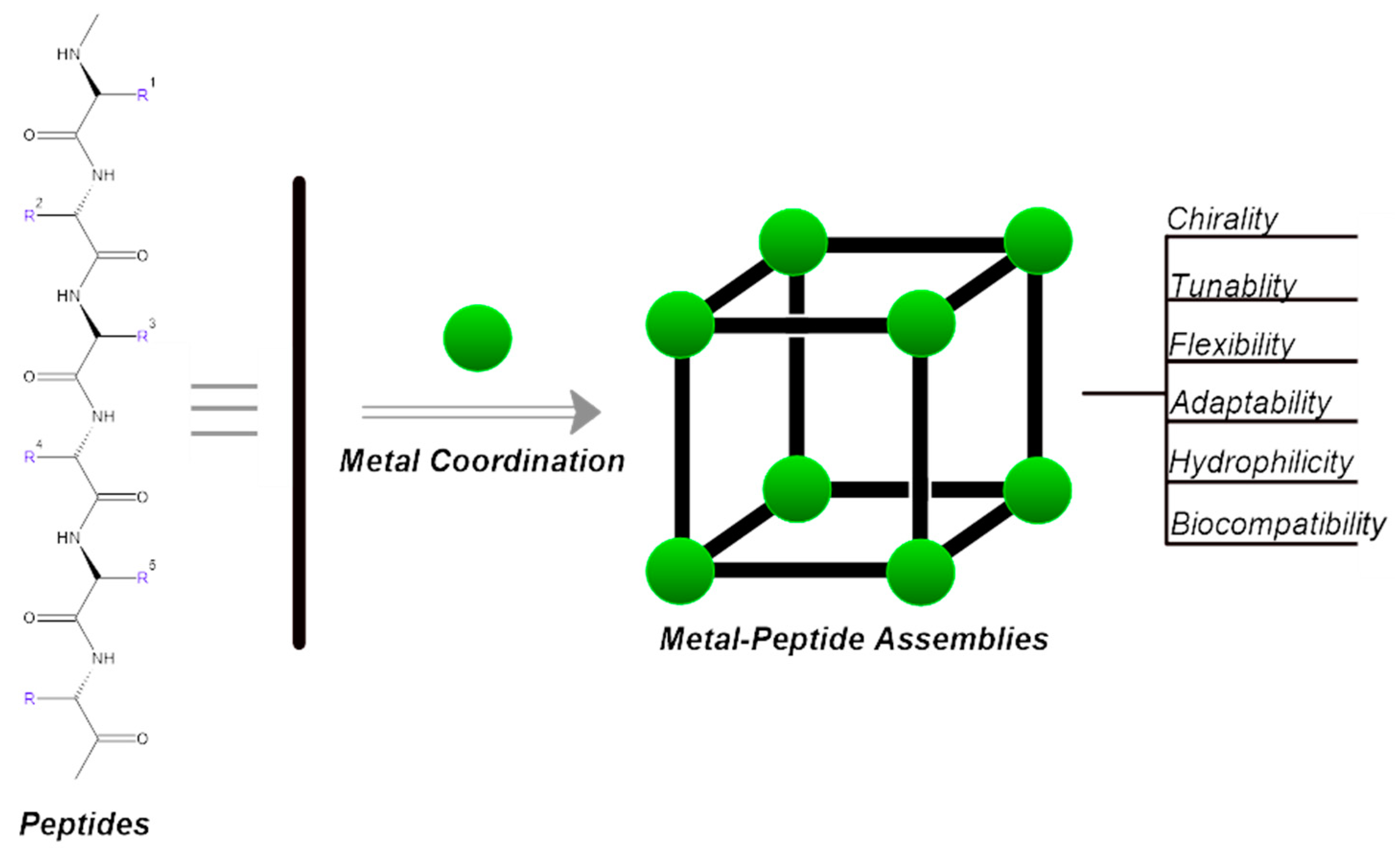

- Wang, C.; Fu, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, Y. A Mini-Review on Peptide-Based Self-Assemblies and Their Biological Applications. Nanotechnology 2021, 33, 062004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Rodriguez, B.J.; Yang, R.; Yu, B.; Mei, D.; Li, J.; Tao, K.; Gazit, E. Microfabrication of Peptide Self-Assemblies:Inspired by Nature towards Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 6936–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.; Wu, H.; Su, Z. Self-Assembling Peptide-Based Hydrogels: Fabrication, Properties, and Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-Z.; An, H.-W.; Wang, H. Chemical Reactions Trigger Peptide Self-Assembly in Vivo for Tumor Therapy. Chem. Med.Chem. 2021, 16, 2452–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ai, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, X. Peptide-Based Supramolecular Hydrogels for Local Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, R.W.; Chmielewski, J. A Comparison of the Collagen Triple Helix and Coiled-Coil Peptide Building Blocks on Metal Ion-Mediated Supramolecular Assembly. Pept. Sci. 2021, 113, e24190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontz, P.A.; Song, W.J.; Tezcan, F.A. Interfacial Metal Coordination in Engineered Protein and Peptide Assemblies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 19, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y. Artificial Metal–Peptide Assemblies: Bioinspired Assembly of Peptides and Metals through Space and across Length Scales. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17316–17336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puiu, M.; Bala, C. Peptide-Based Biosensors: From Self-Assembled Interfaces to Molecular Probes in Electrochemical Assays. Bioelectrochemistry 2018, 120, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, P.N.; Mervinetsky, E.; Solomon, O.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yitzchaik, S.; Friedler, A. Electrochemical Biosensors Based on Peptide-Kinase Interactions at the Kinase Docking Site. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 207, 114177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synhaivska, O.; Mermoud, Y.; Baghernejad, M.; Alshanski, I.; Hurevich, M.; Yitzchaik, S.; Wipf, M.; Calame, M. Detection of Cu2+ Ions with GGH Peptide Realized with Si-Nanoribbon ISFET. Sensors 2019, 19, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mervinetsky, E.; Alshanski, I.; Tadi, K.K.; Dianat, A.; Buchwald, J.; Gutierrez, R.; Cuniberti, G.; Hurevich, M.; Yitzchaik, S. A Zinc Selective Oxytocin Based Biosensor. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 8, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannoor, M.S.; Zhang, S.; Link, A.J.; McAlpine, M.C. Electrical Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria via Immobilized Antimicrobial Peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19207–19212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillehoj, P.B.; Kaplan, C.W.; He, J.; Shi, W.; Ho, C.-M. Rapid, Electrical Impedance Detection of Bacterial Pathogens Using Immobilized Antimicrobial Peptides. SLAS Technol. 2014, 19, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Netto, F.M.; Bertoldo-Pacheco, M.T.; Alegría, A.; Cilla, A. Peptide-Metal Complexes: Obtention and Role in Increasing Bioavailability and Decreasing the pro-Oxidant Effect of Minerals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1470–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Q.; Fan, Y.; Hao, L.; Wang, J.; Xia, C.; Wang, J.; Hou, H. A Comprehensive Review of Calcium and Ferrous Ions Chelating Peptides: Preparation, Structure and Transport Pathways. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Looij, S.M.; Hebels, E.R.; Viola, M.; Hembury, M.; Oliveira, S.; Vermonden, T. Gold Nanoclusters: Imaging, Therapy, and Theranostic Roles in Biomedical Applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022, 33, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, A.M.; Peacock, A.F.A. De Novo Designed Coiled Coils as Scaffolds for Lanthanides, Including Novel Imaging Agents with a Twist. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6851–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzano, S.; Sardo, A.; Blasio, M.; Chahine, T.B.; Dell’Anno, F.; Sansone, C.; Brunet, C. Microalgal Metallothioneins and Phytochelatins and Their Potential Use in Bioremediation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Selvamani, V.; Yoo, I.-K.; Kim, T.W.; Hong, S.H. A Novel Strategy for the Microbial Removal of Heavy Metals: Cell-Surface Display of Peptides. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2021, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.M.F.; Bataglioli, J.C.; Storr, T. Metal Complexes That Bind to the Amyloid-_ Peptide of Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 412, 213255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

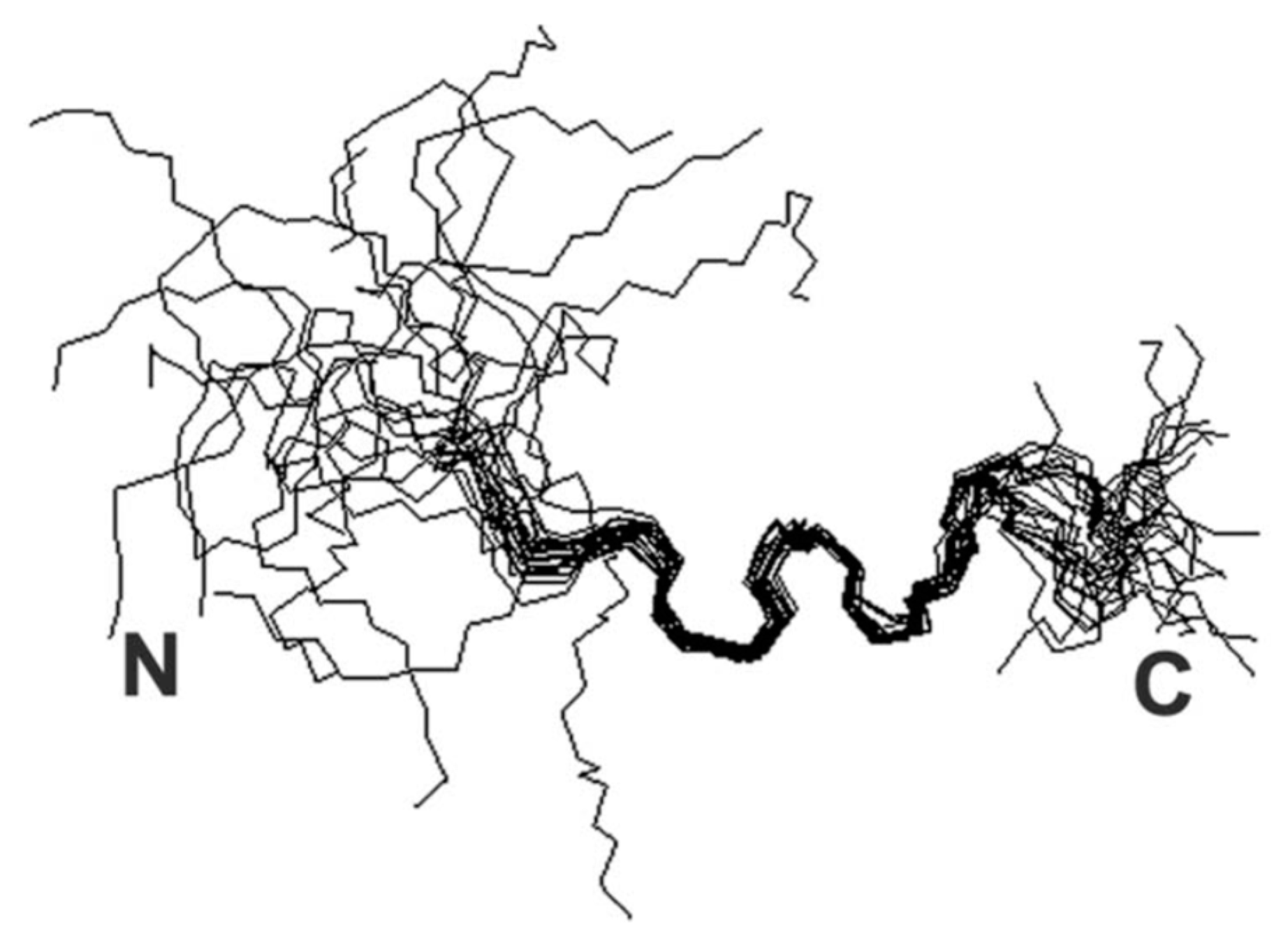

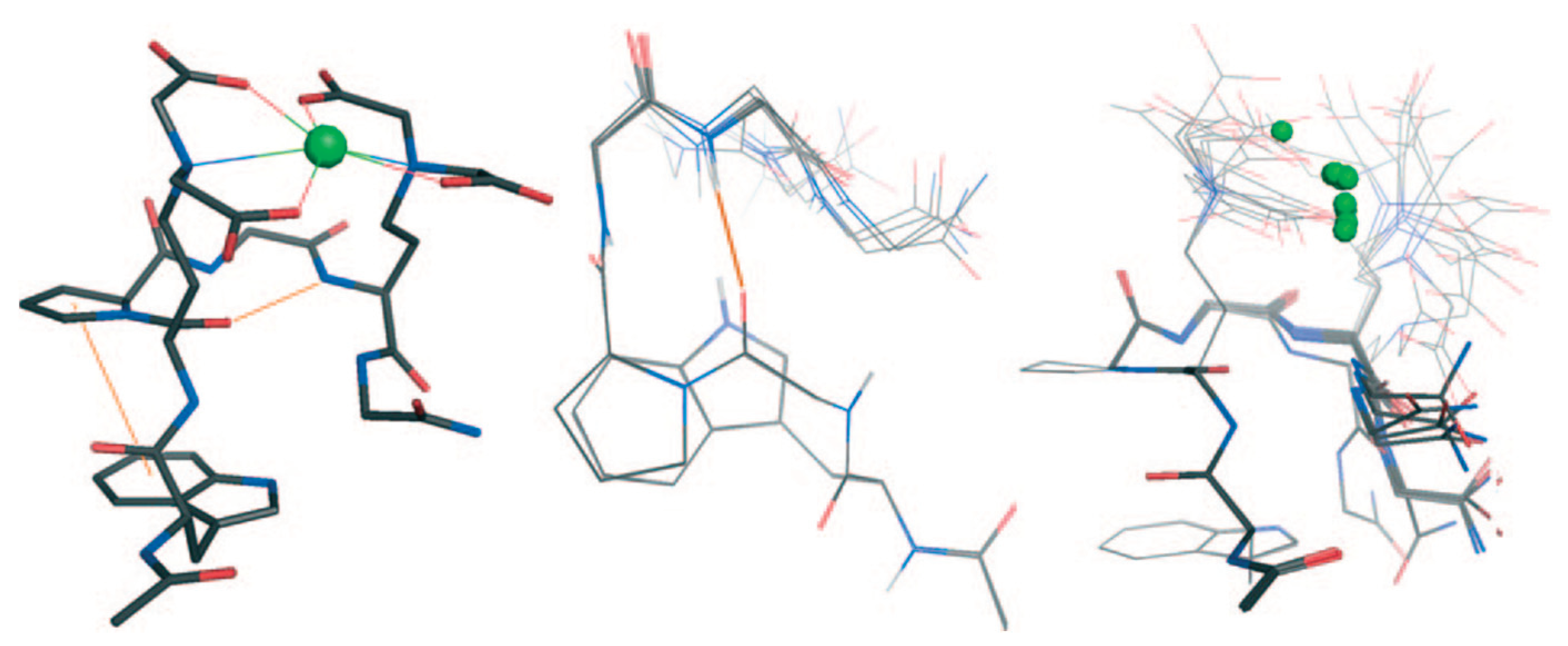

- Shalev, D.E. Studying Peptide-Metal Ion Complex Structures by Solution-State NMR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W. Zinc in Cellular Regulation: The Nature and Significance of “Zinc Signals”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, C.; Otting, G. Pseudocontact Shifts in Biomolecular NMR Using Paramagnetic Metal Tags. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2017, 98–99, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

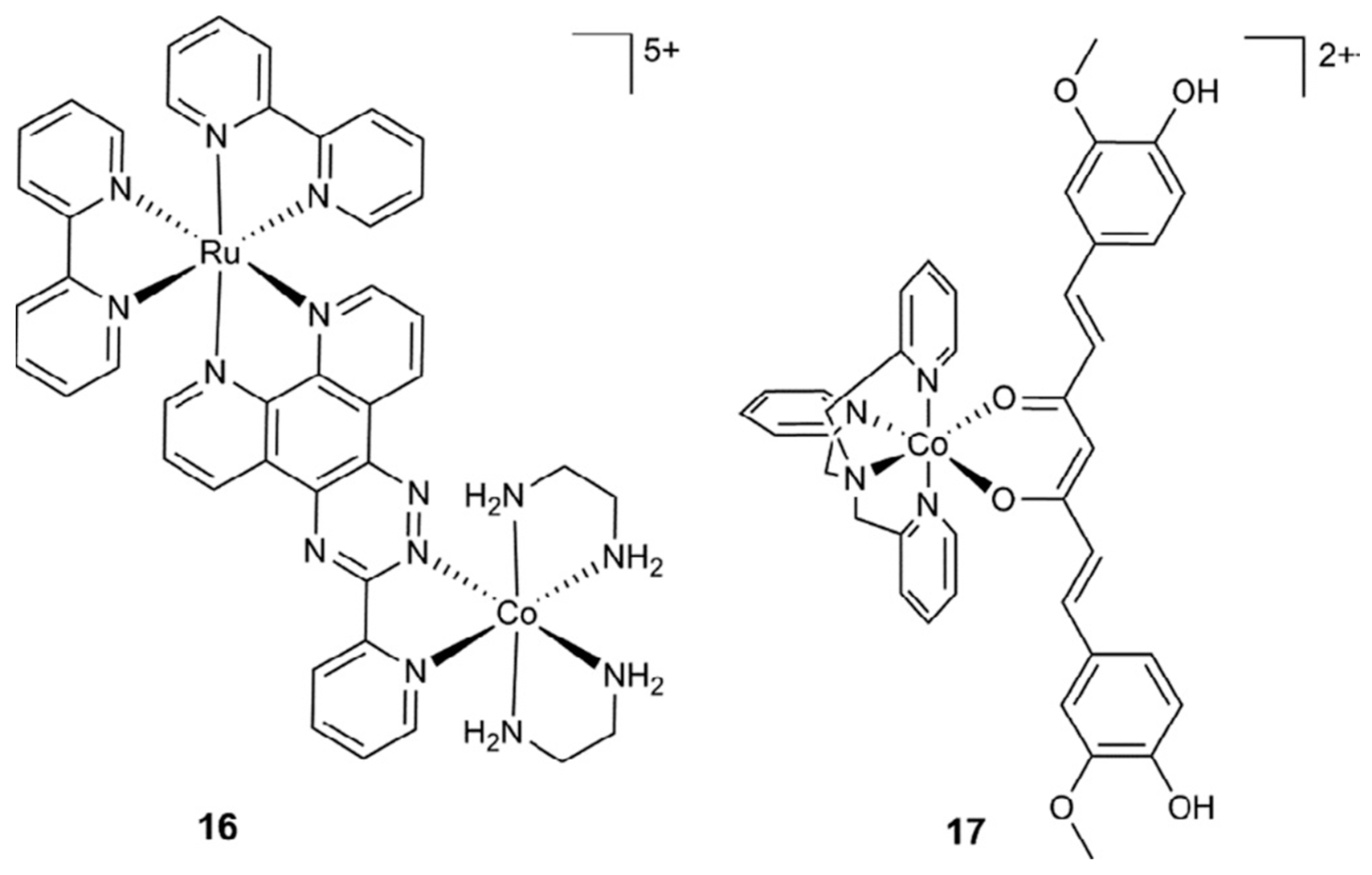

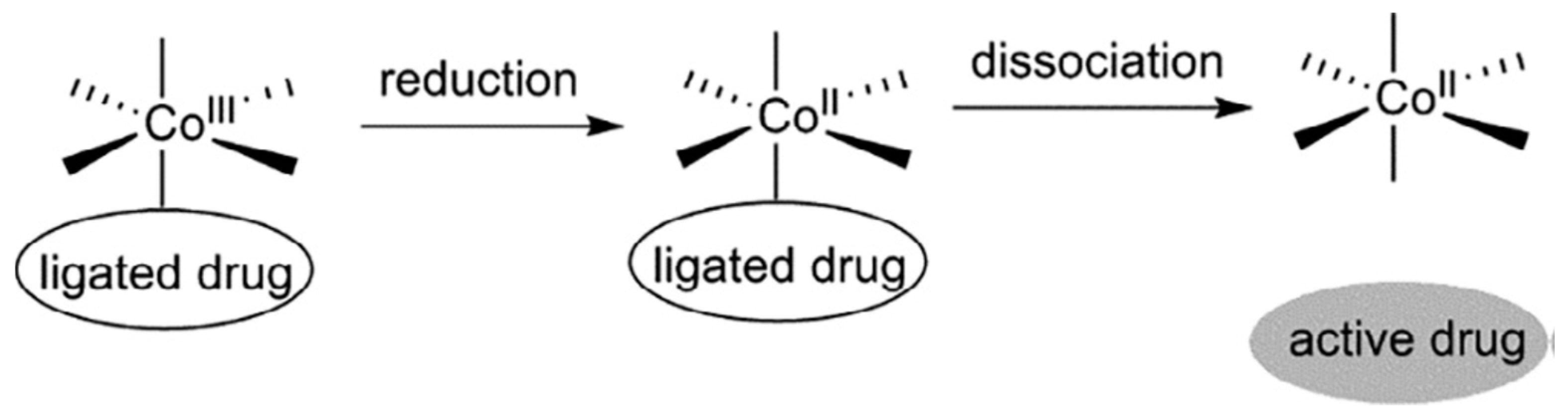

- Renfrew, A.K.; O’Neill, E.S.; Hambley, T.W.; New, E.J. Harnessing the Properties of Cobalt Coordination Complexes for Biological Application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 375, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, P.; Enns, C.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Chemistry and Biology of Eukaryotic Iron Metabolism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 940–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

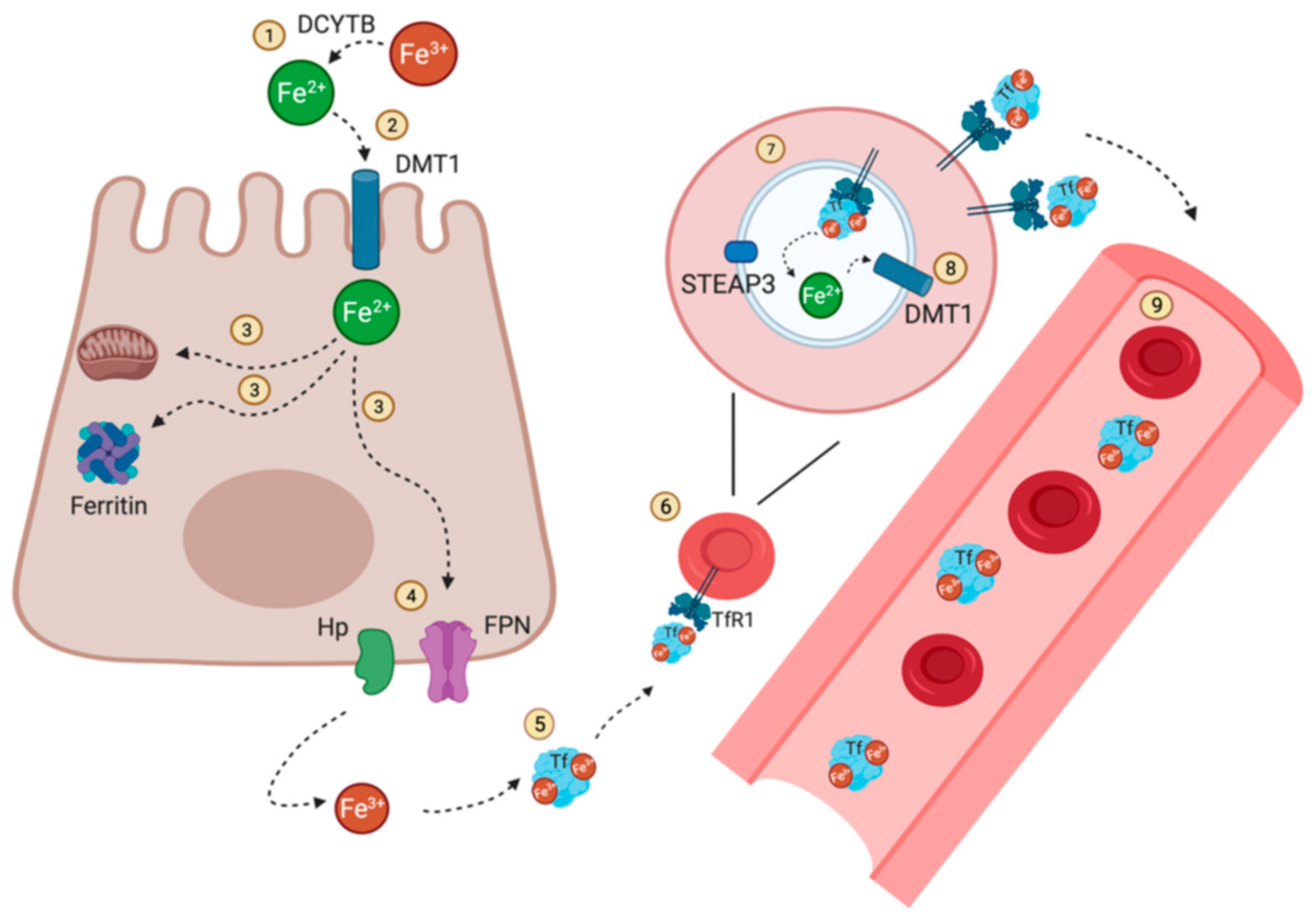

- Vogt, A.-C.S.; Arsiwala, T.; Mohsen, M.; Vogel, M.; Manolova, V.; Bachmann, M.F. On Iron Metabolism and Its Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

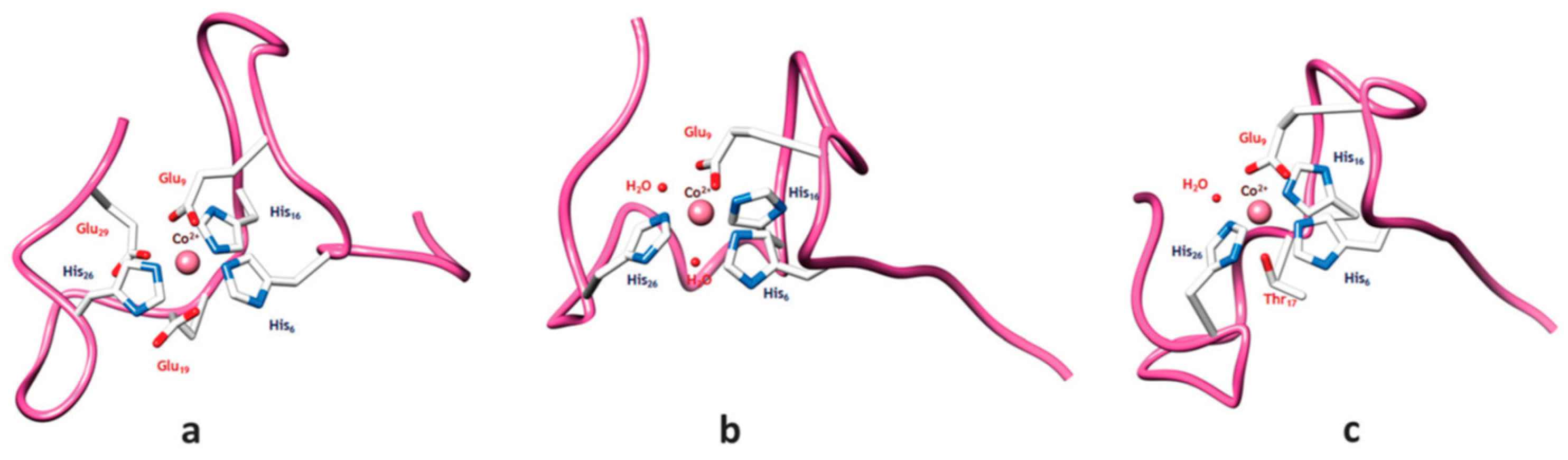

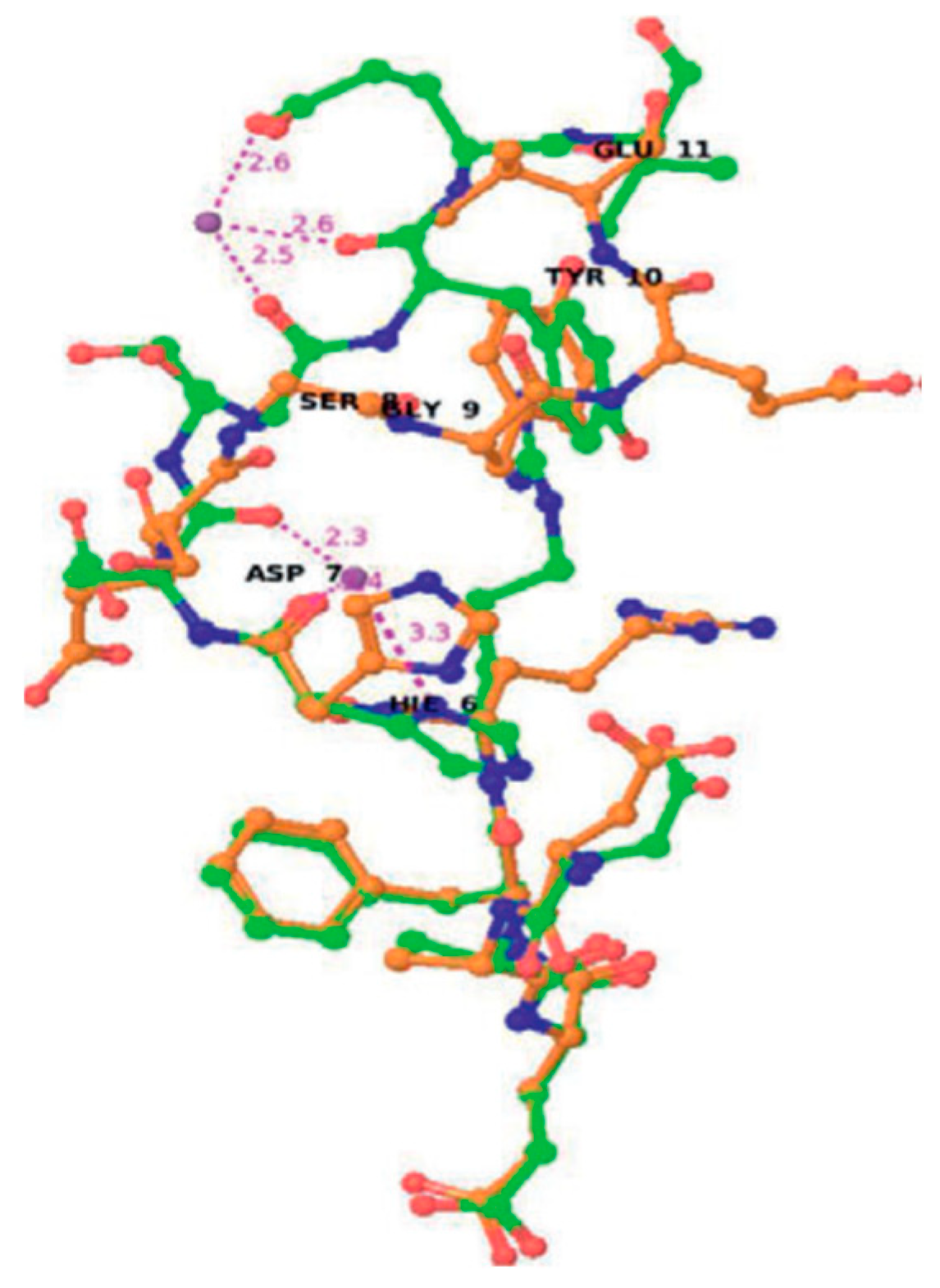

- Istrate, A.N.; Tsvetkov, P.O.; Mantsyzov, A.B.; Kulikova, A.A.; Kozin, S.A.; Makarov, A.A.; Polshakov, V.I. NMR Solution Structure of Rat A Beta(1-16): Toward Understanding the Mechanism of Rats’ Resistance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

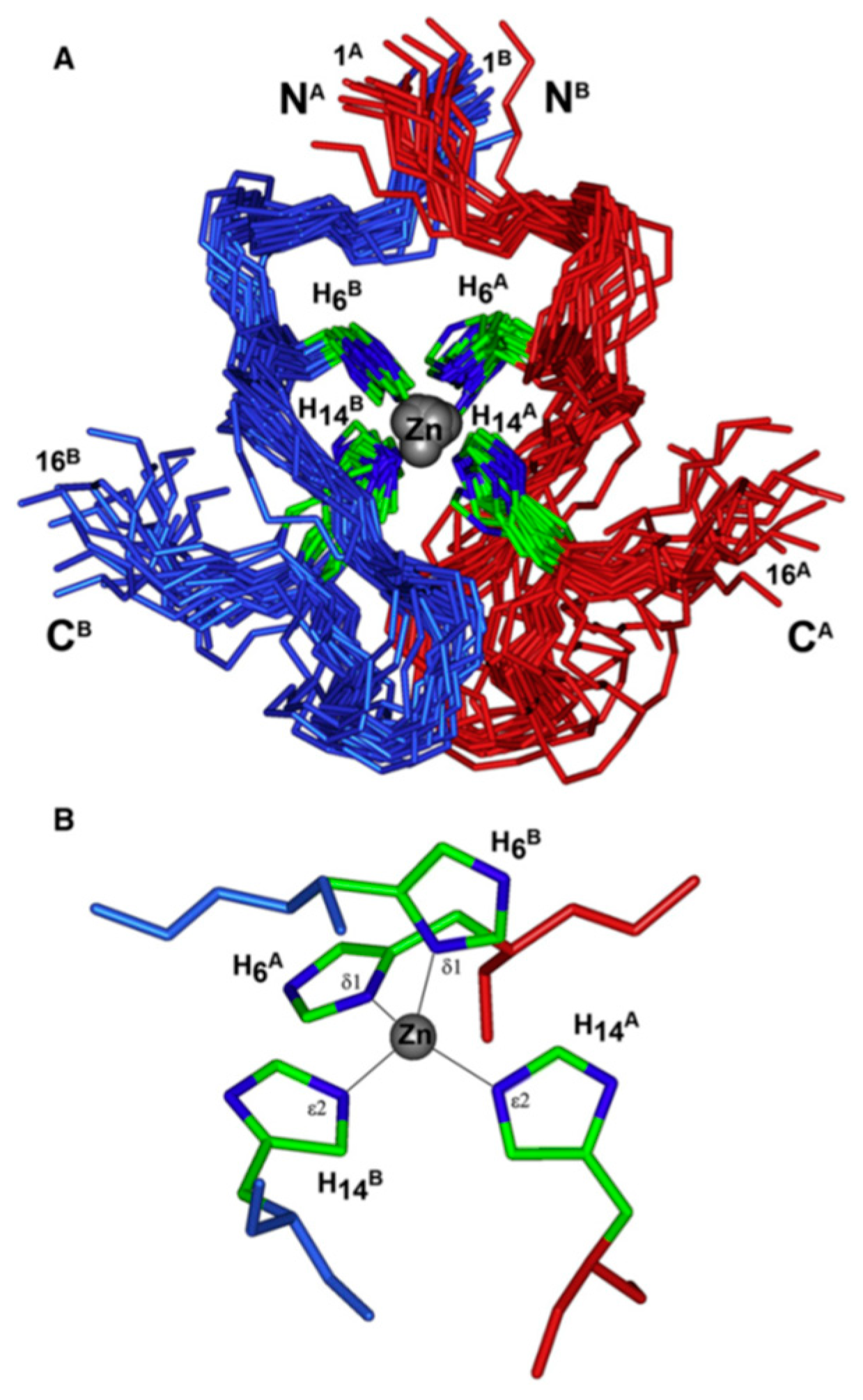

- Polshakov, V.I.; Mantsyzov, A.B.; Kozin, S.A.; Adzhubei, A.A.; Zhokhov, S.S.; van Beek, W.; Kulikova, A.A.; Indeykina, M.I.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Makarov, A.A. A Binuclear Zinc Interaction Fold Discovered in the Homodimer of Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Fragment with Taiwanese Mutation D7H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11734–11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

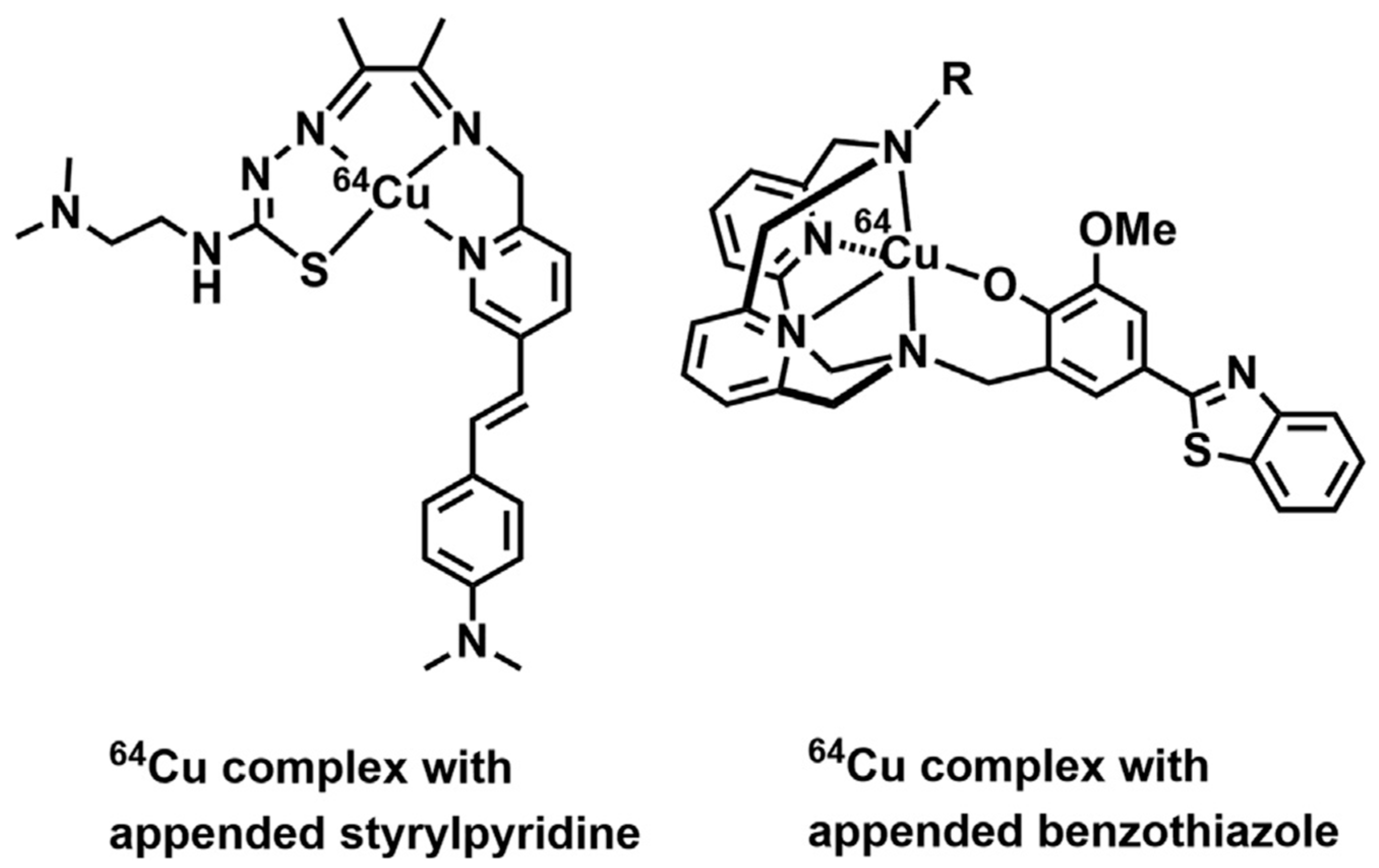

- Hickey, J.L.; Lim, S.; Hayne, D.J.; Paterson, B.M.; White, J.M.; Villemagne, V.L.; Roselt, P.; Binns, D.; Cullinane, C.; Jeffery, C.M.; Price, R.I.; Barnham, K.J.; Donnelly, P.S. Diag-nostic Imaging Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease: Copper Radiopharmaceuticals that Target Aβ Plaques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16120–16132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Bandmann, O. Chapter 2—Epidemiology and Introduction to the Clinical Presentation ofWilson Disease. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Członkowska, A., Schilsky, M.L., Eds.; Wilson Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 142, pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

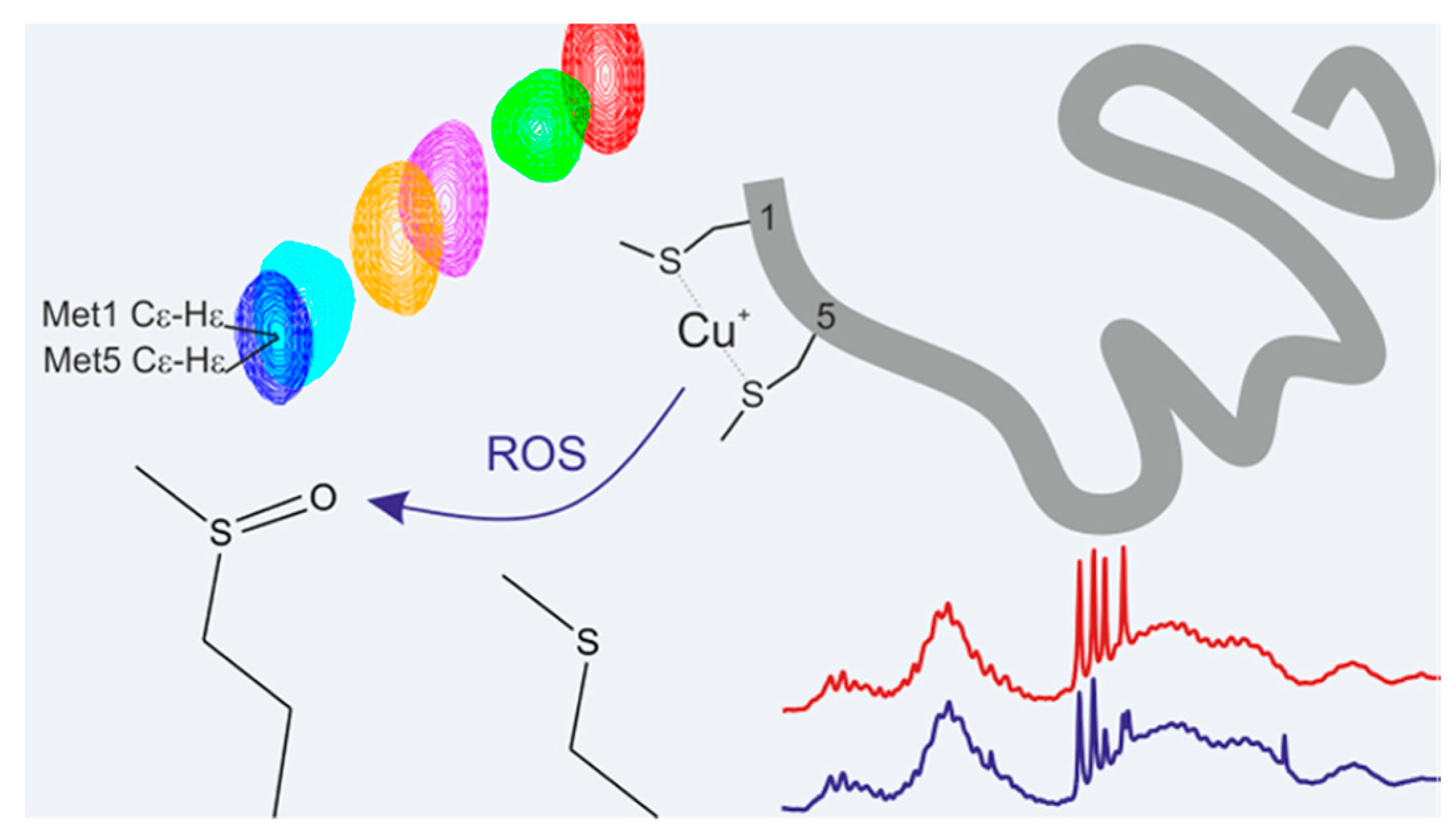

- Miotto, M.C.; Rodriguez, E.E.; Valiente-Gabioud, A.A.; Torres-Monserrat, V.; Binolfi, A.; Quintanar, L.; Zweckstetter, M.; Griesinger, C.; Fernández, C.O. Site-Specific Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation of α-Synuclein: Tightening the Link between Metal Binding and Protein Oxidative Damage in Parkinson’s Disease. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 4350–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remelli, M.; Peana, M.; Medici, S.; Ostrowska, M.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E.; Zoroddu, M.A. Manganism and Parkinson’s Disease: Mn(II) and Zn(II) Interaction with a 30-Amino Acid Fragment. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 5151–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaler, S.G. Menkes Disease. In Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences, 2nd ed.; Aminoff, M.J., Daroff, R.B., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1082–1089. ISBN 978-0-12-385158-1. [Google Scholar]

- Festa, R.A.; Thiele, D.J. Copper: An Essential Metal in Biology. Curr Biol 2011, 21, R877–R883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan, M.S.; Tshuva, E.Y.; Shalev, D.E. Structure and Coordination Determination of Peptide-Metal Complexes Using 1D and 2D H-1 NMR. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 82, e50747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan, M.S.; Dekel, N.; Goch, W.; Shalev, D.E.; Danieli, T.; Lebendiker, M.; Bal, W.; Tshuva, E.Y. Unbound Position II in MXCXXC Metallochaperone Model Peptides Impacts Metal Binding Mode and Reactivity: Distinct Similarities to Whole Proteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 159, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gregorio, G.; Biasotto, F.; Hecel, A.; Luczkowski, M.; Kozlowski, H.; Valensin, D. Structural Analysis of Copper(I) Interaction with Amyloid _ Peptide. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 195, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertini, I.; Ciurli, S.; Dikiy, A.; Fernàndez, C.O.; Luchinat, C.; Safarov, N.; Shumilin, S.; Vila, A.J. The First Solution Structure of a Paramagnetic Copper(II) Protein: The Case of Oxidized Plastocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 2405–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

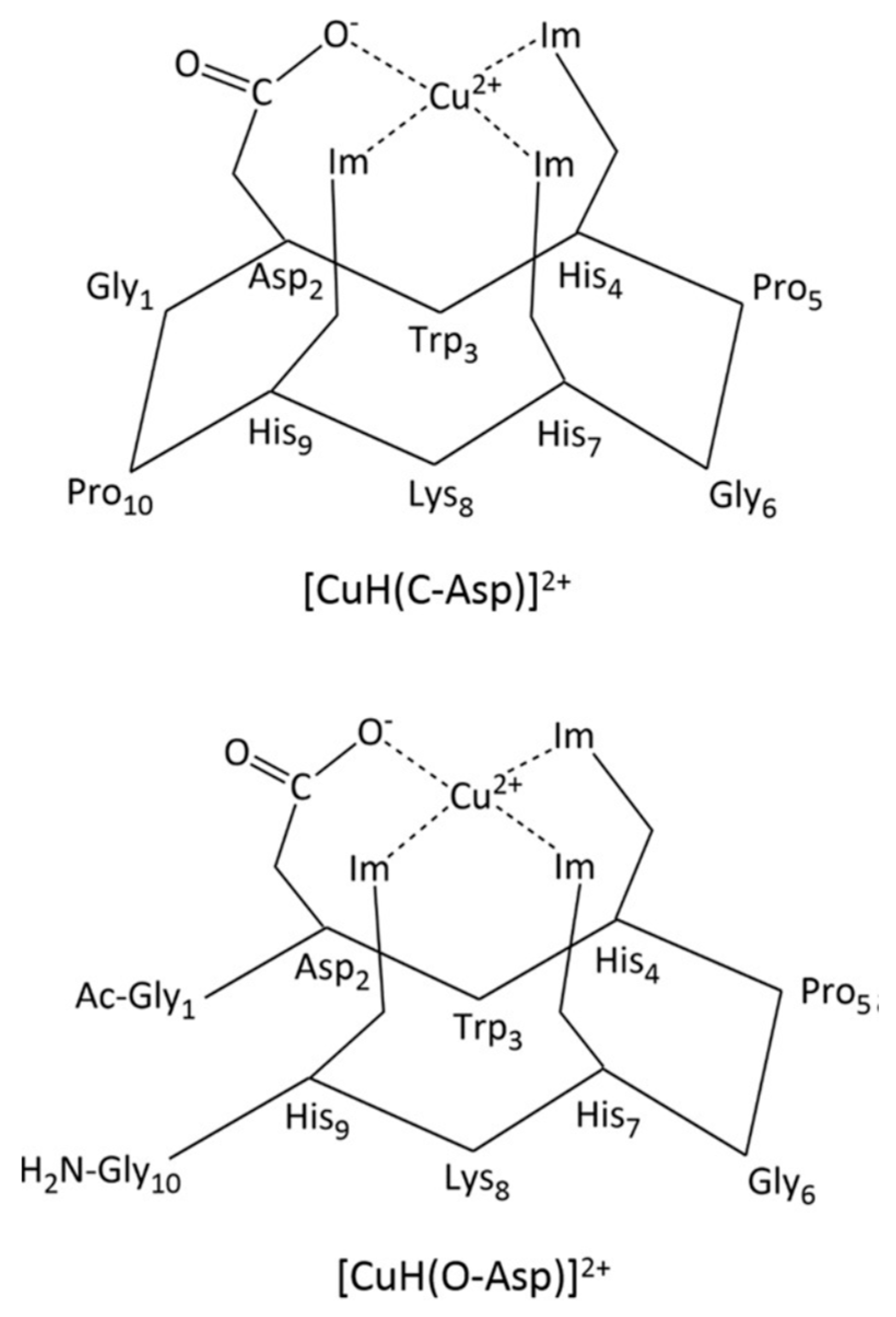

- Fragoso, A.; Carvalho, T.; Rousselot-Pailley, P.; Correia dos Santos, M.M.; Delgado, R.; Iranzo, O. Effect of the Peptidic Scaffold in Copper(II) Coordination and the Redox Properties of Short Histidine-Containing Peptides. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 13100–13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshanski, I.; Shalev, D.E.; Yitzchaik, S.; Hurevich, M. Determining the Structure and Binding Mechanism of Oxytocin-Cu2+ Complex Using Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement NMR Analysis. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancs, Á.; Selmeczi, K.; May, N.V.; Gajda, T. On the Copper(II) Binding of Asymmetrically Functionalized Tripodal Peptides: Solution Equilibrium, Structure, and Enzyme Mimicking. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 7746–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamysz, E.; Kotynia, A.; Czyznikowska, ˙ Z.; Jaremko, M.; Jaremko, Ł.; Nowakowski, M.; Brasun, J. Sialorphin and Its Analog as ˙ Ligands for Copper(II) Ions. Polyhedron 2013, 55, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, S.; Todorov, P.; Staneva, D.; Grozdanov, P.; Nikolova, I.; Grabchev, I. Met-al–Peptide Complexes with Antimicrobial Potential for Cotton Fiber Protection, J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

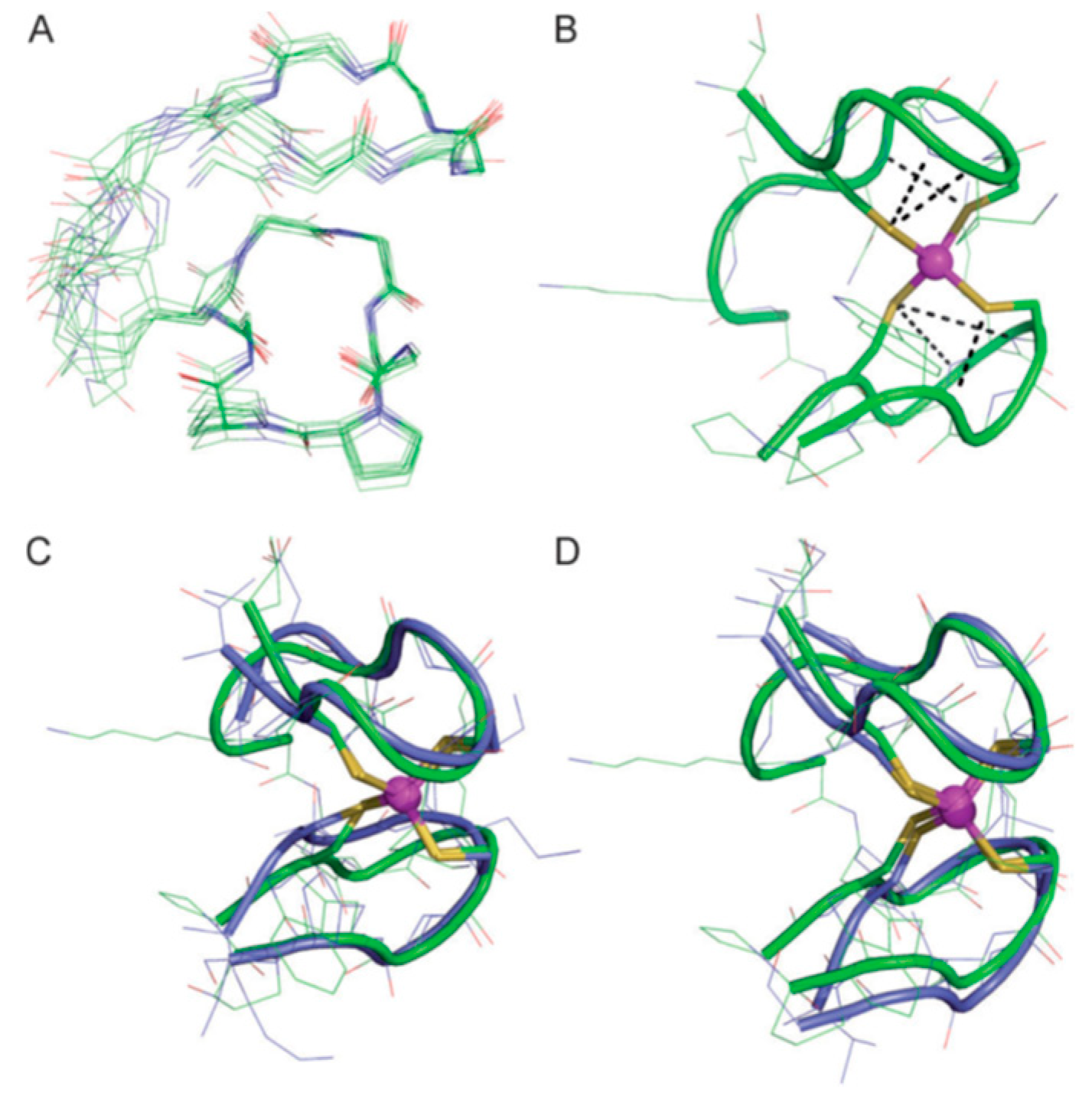

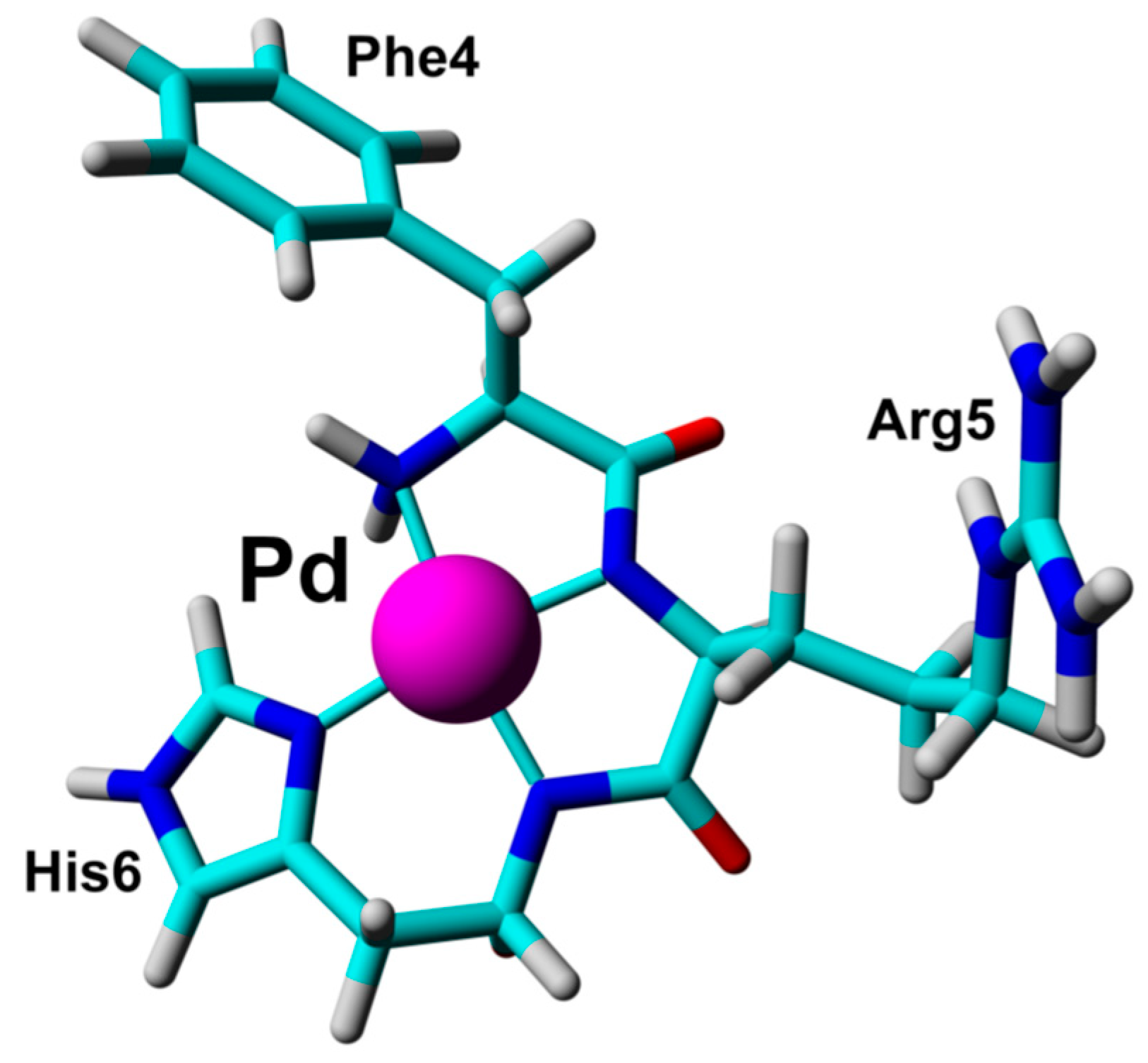

- Mital, M.; Szutkowski, K.; Bossak-Ahmad, K.; Skrobecki, P.; Drew, S.C.; Poznanski, J.; Zhukov, I.; Fraczyk, T.; Bal, W. The Palladium(II) Complex of A Beta(4-16) as Suitable Model for Structural Studies of Biorelevant Copper(II) Complexes of NTruncated Beta-Amyloids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Guan, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Reconstruction of a Helical Trimer by the Second Transmembrane Domain of Human Copper Transporter 2 in Micelles and the Binding of the Trimer to Silver. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 4335–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remelli, M.; Valensin, D.; Toso, L.; Gralka, E.; Guerrini, R.; Marzola, E.; Kozłowski, H. Thermodynamic and Spectroscopic Investigation on the Role of Met Residues in CuII Binding to the Non-Octarepeat Site of the Human Prion Protein. Metallomics 2012, 4, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, I.M.; Vranic, M.; Hoffmann, H.; El-Khatib, A.H.; Montes-Bayón, M.; Möller, H.M.; Weller, M.G. Investigations of the Copper Peptide Hepcidin-25 by LC-MS/MS and NMR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, S.; Mirats, A.; Caballero, A.B.; Guirado, G.; Barrios, L.A.; Teat, S.J.; Rodriguez-Santiago, L.; Sodupe, M.; Gamez, P. Drastic Effect of the Peptide Sequence on the Copper-Binding Properties of Tripeptides and the Electrochemical Behaviour of Their Copper(II) Complexes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5153–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klose, D.; Vemulapalli, S.P.B.; Richman, M.; Rudnick, S.; Aisha, V.; Abayev, M.; Chemerovski, M.; Shviro, M.; Zitoun, D.; Majer, K.; et al. Cu2+-Induced Self-Assembly and Amyloid Formation of a Cyclic D,L-α-Peptide: Structure and Function. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 6699–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felten, A.-S.; Pellegrini-Moïse, N.; Selmeczi, K.; Henry, B.; Chapleur, Y. Synthesis and Copper(II)-Complexation Properties of an Unusual Macrocyclic Structure Containing α/β-Amino Acids and Anomeric Sugar β-Amino Acid. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 5645–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, C.; Cortés-Mejía, R.; Miotto, M.C.; Binolfi, A.; Fernández, C.O.; del Campo, J.M.; Quintanar, L. Copper Coordination Features of Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide: The Type 2 Diabetes Peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 10727–10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreini, C.; Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Rosato, A. Counting the Zinc-Proteins Encoded in the Human Genome. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Nakatani, A.; Saito, K. The Unique N-Terminal Zinc Finger of Synaptotagmin-like Protein 4 Reveals FYVE Structure. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 2451–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Uechi, A.; Saito, K. The Zinc Finger Domain of RING Finger Protein 141 Reveals a Unique RING Fold. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

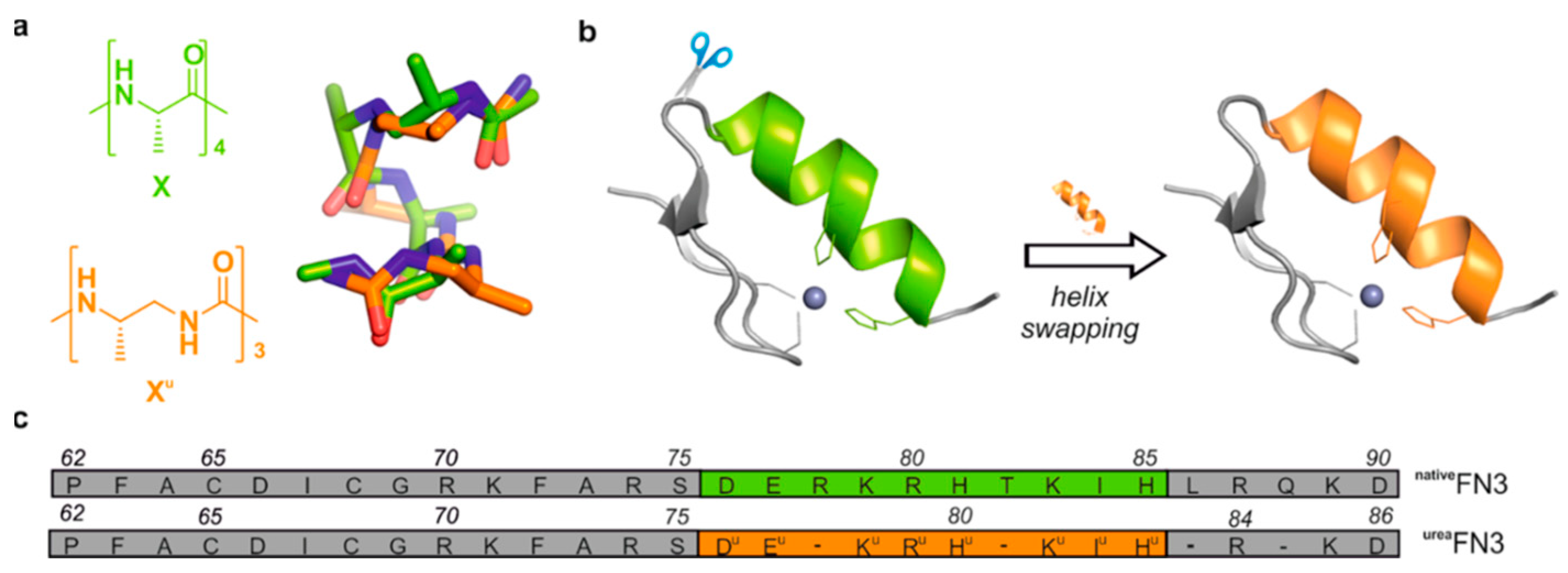

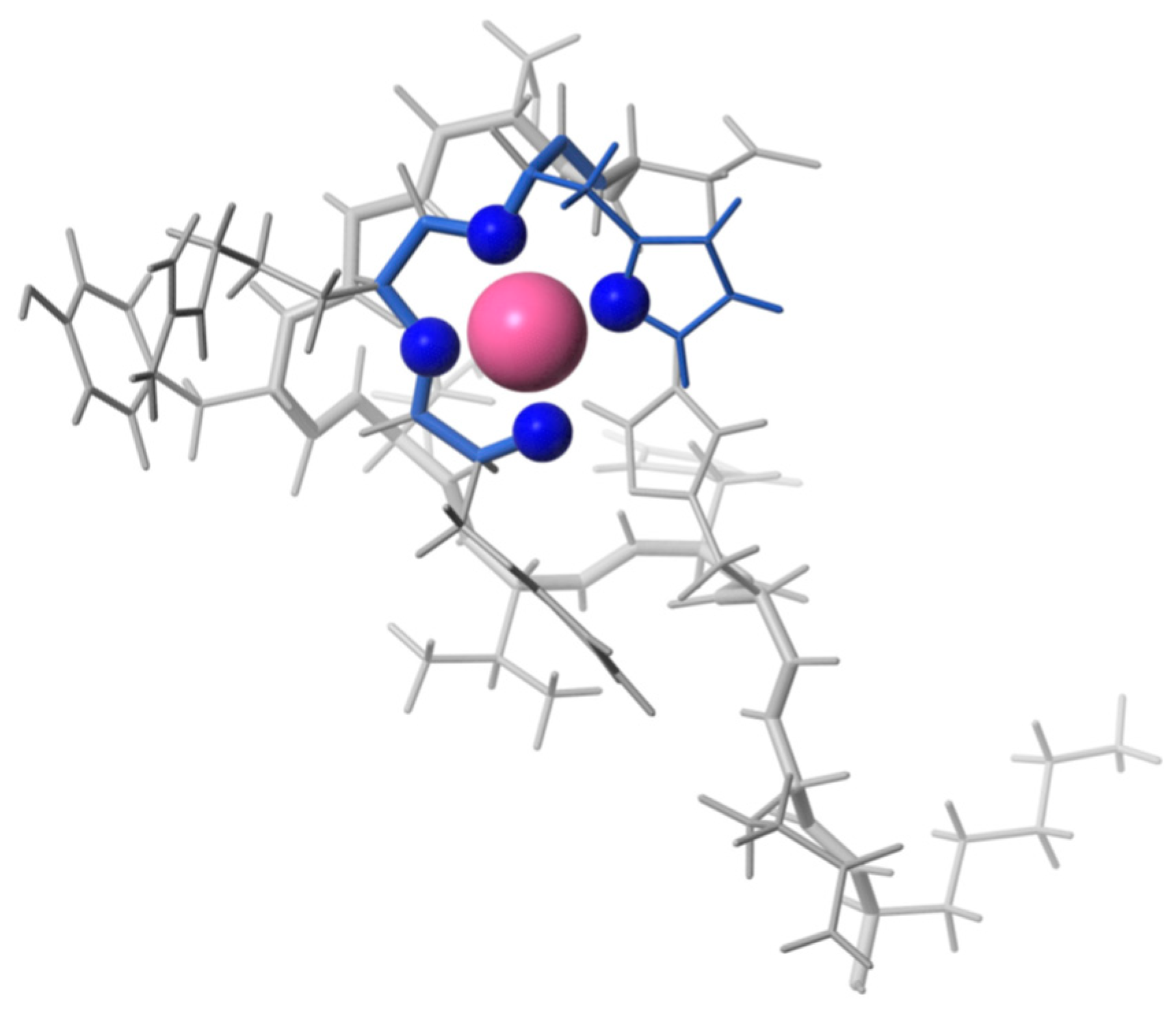

- Lombardo, C.M.; Kumar, M.V.V.; Douat, C.; Rosu, F.; Mergny, J.-L.; Salgado, G.F.; Guichard, G. Design and Structure Determination of a Composite Zinc Finger Containing a Nonpeptide Foldamer Helical Domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2516–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.; Mettra, B.; Lebrun, V.; Latour, J.-M.; Sénèque, O. On the Design of Zinc-Finger Models with Cyclic Peptides Bearing a Linear Tail. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3921–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.R.; Horne, W.S. Proteomimetic Zinc Finger Domains with Modified Metal-Binding Beta-Turns. Pept. Sci. 2020, 112, e24177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.L.; Kovermann, M.; Thomas, F. Switchable Zinc(II)-Responsive Globular β-Sheet Peptide. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, A.; Nastri, F.; Marasco, D.; Maglio, O.; De Sanctis, G.; Sinibaldi, F.; Santucci, R.; Coletta, M.; Pavone, V. Design of a New Mimochrome with Unique Topology. Chem.—Eur. J. 2003, 9, 5643–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

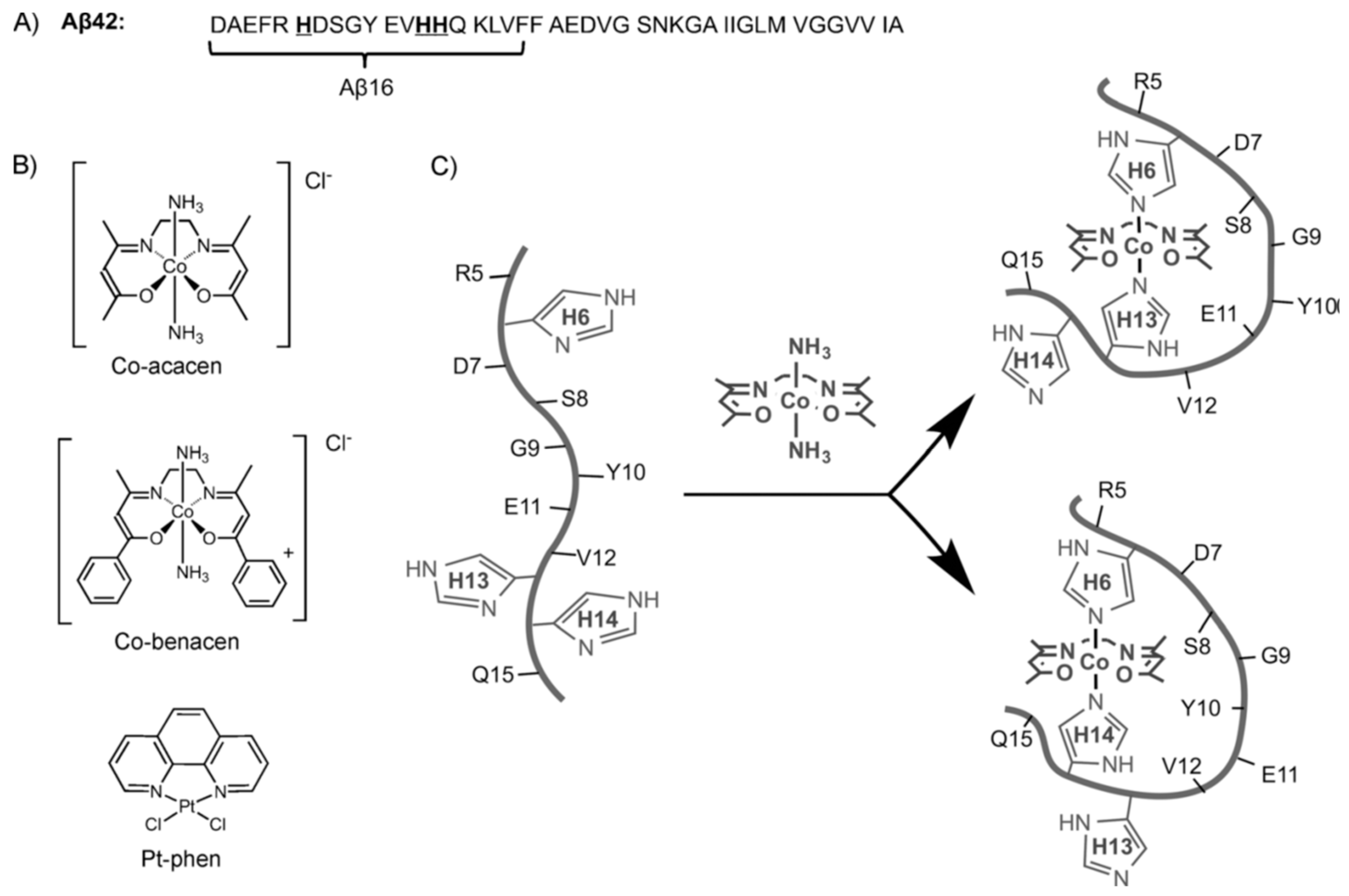

- Heffern, M.C.; Velasco, P.T.; Matosziuk, L.M.; Coomes, J.L.; Karras, C.; Ratner, M.A.; Klein, W.L.; Eckermann, A.L.; Meade, T.J. Modulation of Amyloid-β Aggregation by Histidine-Coordinating Cobalt(III) Schiff Base Complexes. Chem.Bio.Chem. 2014, 15, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizullina, A.R.; Blokhin, D.S.; Kusova, A.M.; Klochkov, V.V. Investigation of the Effect of Transition Metals (MN, CO, GD) on the Spatial Structure of Fibrinopeptide B by NMR Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1204, 127484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, M.; Medici, S.; Nurchi, V.M.; Crisponi, G.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Zoroddu, M.A. Manganese and Cobalt Binding in a MultiHistidinic Fragment. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 16293–16301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Bang, K.-M.; Ha, H.; Cho, N.H.; Namgung, S.D.; Im, S.W.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, R.M.; Choi, W.I.; Lim, Y.-C.; et al. Tyrosyltyrosylcysteine-Directed Synthesis of Chiral Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles and Peptide Conformation Analysis. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, D.S.; Agudelo, W.A.; Yone, A.; Vizioli, N.; Arán, M.; Flecha, F.L.G.; Lebrero, M.C.G.; Santos, J. A Helix–Coil Transition Induced by the Metal Ion Interaction with a Grafted Iron-Binding Site of the CyaY Protein Family. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2370–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, H.; Lee, Y.-Z.; Hung, Y.-L.; Kolusheva, S.; Upcher, A.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Sue, S.-C.; Zarivach, R. Understanding the Biomineralization Role of Magnetite-Interacting Components (MICs) From Magnetotactic Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

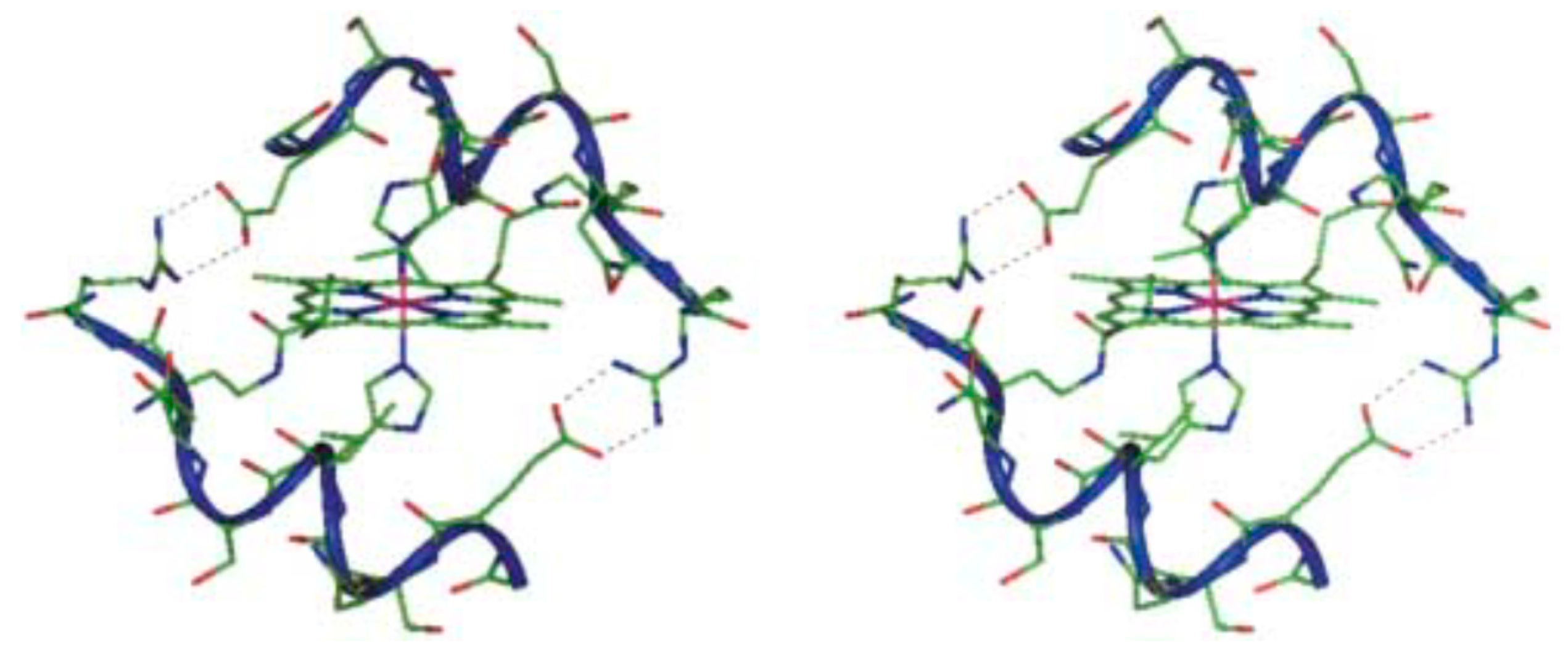

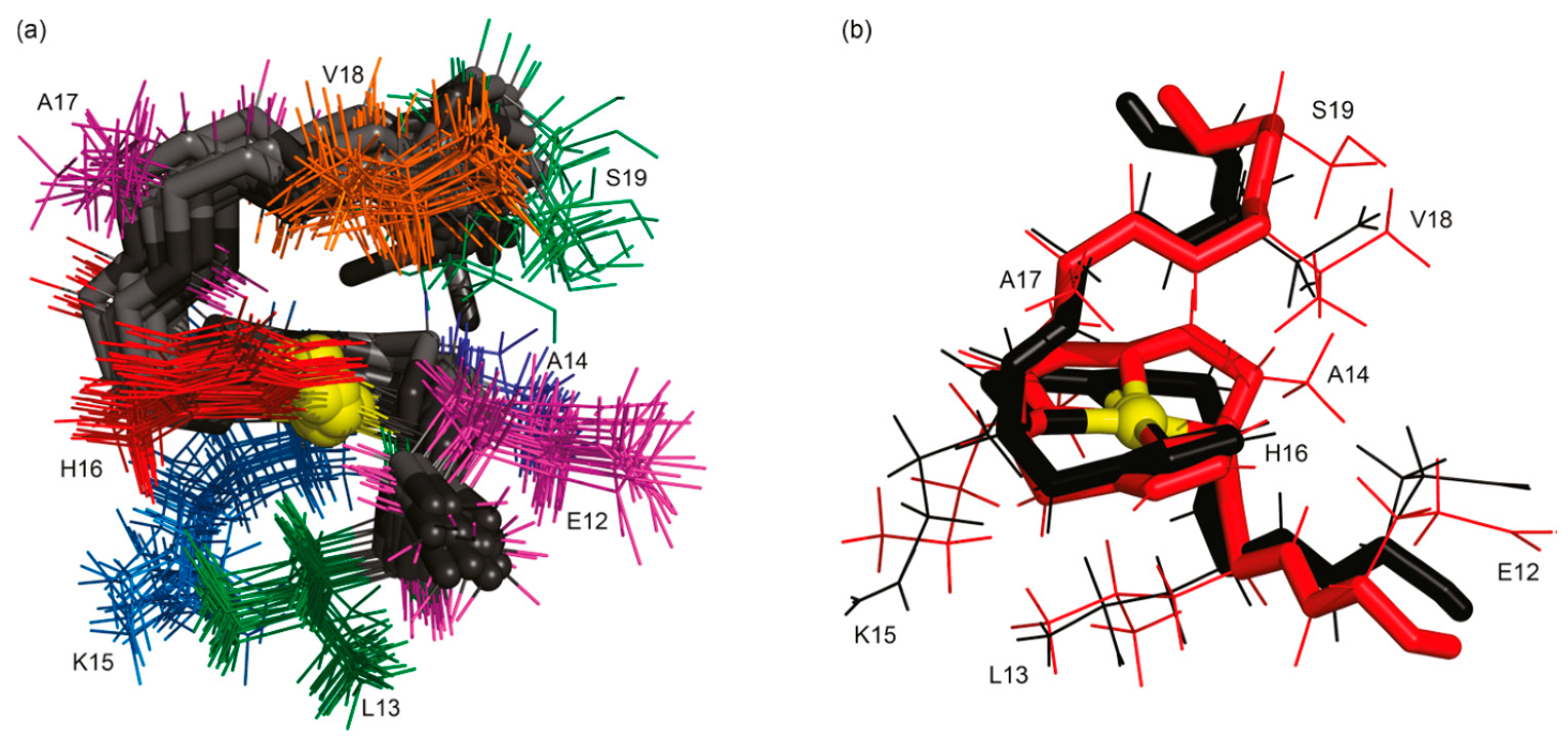

- Gómez-González, J.; Pérez, Y.; Sciortino, G.; Roldan-Martín, L.; Martínez-Costas, J.; Maréchal, J.-D.; Alfonso, I.; Vázquez López, M.; Vázquez, M.E. Dynamic Stereoselection of Peptide Helicates and Their Selective Labeling of DNA Replication Foci in Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 8859–8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inubushi, T.; Becker, E.D. Efficient Detection of Paramagnetically Shifted NMR Resonances by Optimizing the WEFT Pulse Sequence. J. Magn. Reson. (1969) 1983, 51, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Pletneva, E.V. Ligation and Reactivity of Methionine-Oxidized Cytochrome c. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 5754–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, P.; Krishnarjuna, B.; Vishwanathan, V.; Jagadeesh Kumar, D.; Babu, S.; Ramanathan, K.V.; Easwaran, K.R.K.; Nagendra, H.G.; Raghothama, S. Does Aluminium Bind to Histidine? An NMR Investigation of Amyloid B12 and Amyloid B16 Fragments. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 82, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.E.; Klewpatinond, M.; Abdelraheim, S.R.; Brown, D.R.; Viles, J.H. Probing Copper2+ Binding to the Prion Protein Using Diamagnetic Nickel2+ and 1H NMR: The Unstructured N Terminus Facilitates the Coordination of Six Copper2+ Ions at Physiological Concentrations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 346, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasmi, G.; Singer, A.; Forman-Kay, J.; Sarkar, B. NMR Structure of Neuromedin C, a Neurotransmitter with an Amino Terminal CuII-, NiII-Binding (ATCUN) Motif. J. Pept. Res. 1997, 49, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.M.; Zavitsanos, K.; Del Conte, R.; Malandrinos, G.; Hadjiliadis, N. The Possible Role of 94−125 Peptide Fragment of Histone H2B in Nickel-Induced Carcinogenesis. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 5658–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoroddu, M.A.; Peana, M.; Medici, S.; Potocki, S.; Kozlowski, H. Ni(II) Binding to the 429–460 Peptide Fragment from Human Toll like Receptor (HTLR4): A Crucial Role for Nickel-Induced Contact Allergy? Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pochapsky, T.C.; Kuti, M.; Kazanis, S. The Solution Structure of a Gallium-Substituted Putidaredoxin Mutant: GaPdx C85S. J. Biomol. NMR 1998, 12, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, A.P.; Jones, C.E.; Viles, J.H. A Survey of Diamagnetic Probes for Copper2+ Binding to the Prion Protein. 1H NMR Solution Structure of the Palladium2+ Bound Single Octarepeat. Dalton Trans. 2006, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monger, L.J.; Runarsdottir, G.R.; Suman, S.G. Directed Coordination Study of [Pd(En)(H2O)2 ]2+ with Hetero-Tripeptides Containing C-Terminus Methyl Esters Employing NMR Spectroscopy. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 25, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiveriotis, P.; Hadjiliadis, N. Studies on the Interaction of Histidyl Containing Peptides with Palladium(II) and Platinum(II) Complex Ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 190–192, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, F. Micelle-Bound Structure of an Extracellular Met-Rich Domain of HCtr1 and Its Binding with Silver. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 15245–15253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, C.M.; Antunes, V.U.; Cardoso, R.S.; Candido, T.Z.; Lima, C.S.P.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; Juliano, M.A.; Favaro, D.C.; Abbehausen, C. Functionalization of New Anticancer Pt(II) Complex with Transferrin Receptor Binding Peptide. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 511, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisnetti, F.; Gateau, C.; Lebrun, C.; Delangle, P. Lanthanide(III) Complexes with Two Hexapeptides Incorporating Unnatural Chelating Amino Acids: Secondary Structure and Stability. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009, 15, 7456–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | References |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s | 27, 34, 35, 36 |

| Wilson's | 37 |

| Parkinson’s | 38, 39 |

| Menkes | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).