Background

Virtual health has become one of the most essential approaches in the healthcare sector to assist in effective and timely healthcare service delivery. The COVID-19 pandemic presented an unprecedented challenge to healthcare professionals and patients globally. They faced safety issues since the disease could be passed from one person to another through contact (Alharbi et al., 2021). Consequently, the adoption of virtual care was accelerated. Virtual care refers to the remote delivery of healthcare services like telemedicine, mHealth, remote patient monitoring, and others using information and communication technologies. While virtual care improves access and reduces costs, delivering quality healthcare virtually requires healthcare professionals to have specific competencies beyond traditional in-person care (Webster, 2020). Leveraging virtual healthcare is especially relevant in Saudi Arabia, which faces a shortage of healthcare professionals and increasing rates of chronic conditions.

According to Alahmari et al. (2022), virtual care is a relatively new concept in many countries, including Saudi Arabia. In the country, virtual healthcare is offered in virtual clinics, which have been introduced recently. Their quality differs based on different settings. Nevertheless, many people view them as the future of healthcare. In their study, Alahmari et al. (2022) found that 87% of Saudi patients who received virtual healthcare in Saudi virtual clinics agreed to some extent that virtual clinics could replace conventional clinics. While most patients involved in the study (86%) were satisfied with the services they received through the virtual clinics, concerns persist over the quality of virtual healthcare (Alahmai et al., 2022). Most of these concerns are associated with healthcare professionals’ ability to transition from conventional face-to-face healthcare to virtual healthcare, often without sufficient training, as was experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alharb et al., 2021).

Literature has continuously proven the increasing number of facilities incorporating virtual health into their system. This aligns with the implications that virtual health will emanate when the health practitioners are well-skilled and equipped with competency-based practices. Health practitioners need these skills and experiences to provide high-quality treatment, effectively use communication equipment to communicate and analyze patients’ data, and understand the requirements of virtual healthcare delivery. “Competencies extend to the administrative aspects of virtual care delivery and the cultivation of positive relationships with patients and their families” (United States, 2022).

Moreover, there is a dearth of research on the core competencies healthcare professionals need for effective virtual care delivery. Identifying these competencies can inform the development of training programs and guidelines to equip healthcare professionals with the skills required for high-quality virtual healthcare delivery (Harrison & Manias, 2022). It can also help Saudi Arabia and other governments worldwide when integrating virtual healthcare as part of their strategies to expand healthcare to their citizens.

Saudi Arabia is one of the countries that have embraced digital health. The Saudi Arabian government currently supports the mainstreaming of digital health. The government of Saudi Arabia has been using technology extensively to promote healthcare service delivery. For instance, after the outbreak of COVID-19, the government of Saudi Arabia started supporting public health precautions to control its spread (Jonasdottir et al., 2022). Some of the digital health systems that the government has used are Tabaud, Seha, and Tetamman to track COVID-19 patients. “This network was formed to use virtual healthcare and telehealth solutions healthcare facilities to connect with primary healthcare centres and hospitals operating in remote locations” (Jonasdottir et al., 2022). These applications have helped in linking healthcare practitioners with patients and, in addition, reduce the need for patients to visit healthcare facilities. According to MOH records, Saudi Arabia has more than two million virtual healthcare service users as of 2022 (Fronczek & Rouhana, 2018).

Saudi Arabia has launched the world’s largest virtual hospital of its kind. SEHA Virtual Hospital (SVH) is the first in the Middle East and North Africa as virtual hospital and the first hospital worldwide to obtain Canadian accreditation. It offers more than 23 specialties and 52 subspecialties (Ministry of Health, 2023). It is connected to a network of over 170 hospitals across all regions in Saudi Arabia. In these hospitals, patients can attend real-time video sessions with the country’s top specialists who provide their required care. They share their vital signs while tests and x-rays are shared with the network of specialists who offer their assessments and healthcare recommendations. The hospital’s specialists provide multiple healthcare services, including emergence and critical advice (such as virtual strokes and electroencephalography), specialized clinics (such as blood diseases, psychiatry, and heart diseases), home care services, and medical support services (including virtual pharmacy services and virtual pathology) (Ministry of Health, 2023).

In addition, to enhance remote patient contact, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) introduced the telemedicine training program. “The government has also supported digitizing Healthcare, especially promoting virtual healthcare adoption and continued use” (Jonasdottir et al., 2022). According to Fronczek and Rouhana (2018), the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia developed a strategy to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare services.

1.1. Aim of the Study

This study’s objective is to close the research gap on healthcare professionals’ competencies in virtual health. It seeks to answer the following research question:

RQ: What competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) are required for healthcare professionals to provide quality virtual healthcare to patients?

Its specific objectives are:

To identify the core competencies required by physicians, nurses, and allied healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia to deliver quality virtual care effectively.

To understand Saudi healthcare professionals’ challenges in adopting virtual care and applying related competencies.

To recommend how training programs and licensing requirements could be enhanced to develop virtual care competencies amongst Saudi healthcare professionals.

To suggest organizational and technological supports to enable Saudi healthcare professionals to integrate virtual care competencies into routine practice.

Research Design

The Delphi method was used for this study which combined both quantitative and qualitative elements, which helped obtain consensus from the experts that was reliable enough to create a comprehensive framework. This method is structured iteratively to gather expert opinions and reach a consensus on a complex problem or issue. It involves a series of rounds of data collection and analysis.

1.1. Study Setting and Participants selection

The study was conducted at SEHA Virtual Hospital in Saudi Arabia. A purposeful sampling technique was used to choose experts based on their quality, knowledge, experience regarding virtual health, and clinical and academic credentials. The study involved 42 participants. These participants were all staff members of the SEHA hospital. The inclusion criterion was having some experience providing virtual healthcare services. Selected participants were requested to complete each round of the Delphi survey within 2–3 weeks of receiving the email for each round. A reminder email was sent to non-responders three days before the deadline to prompt their survey completion. Communication between the researchers and the panelists was via email only so that no expert could exert an undue influence over the opinions of others. Participants were known to the researcher but were not known to the other participants to maintain anonymity among the participants.

1.1. Data Collection and Materials

The participants’ responses were collected from online questionnaires. They responded to the questionnaire online. The questionnaires prompted the participants to provide qualitative and quantitative data.

1.1. Procedure

The Delphi method was used to collect participants’ responses. It involved three rounds. The first questionnaire prompted participants to provide qualitative data. Participants were asked open-ended questions that required them to showcase their knowledge, skills, and attitudes regarding virtual health. They were asked to identify up to ten competencies they believe healthcare professionals need. Participants were also required to provide their demographic data.

In the first round, a questionnaire is anonymously sent to a panel of experts seeking their views on the issue. Then, the researcher summarizes the responses and returns them to the experts for a second round. The scholars could make changes in every round of the experiment (Shariff, 2021), rating and ranking the items using the changes made in each round. This procedure of iterations persisted until a pact was reached. Different justifications prompted choosing this methodology for it in research. For instance, it simplified expert opinion collection from a very diverse group of respondents located in other geographic areas with the aid of a questionnaire and thereby reduced the need for face-to-face gathering.

Besides, the respondents remained anonymous during the entire study and, therefore freely spoke about what they believed were matters on issues of the study. Thus, the Delphi technique allowed several rounds for fine-tuning and responding to the group results; experts appeared ready and then reacted in a conducive fashion, resulting in consensus. This method was also focused on anonymity and allowed experts to share their true viewpoints not subjected the influence of any external factors or in corresponding pressure from co–panelists (Shariff, 2021). Box found it also included structured feedback conjointly multiple rounds of experts to refine their opinions based on social results, thus developing an agreement.

Therefore, the study procedure has produced reliable and realizable findings. Last, given the promulgated method, had followed a structured path, it gave an audit trail indicating how conclusions were attained. Consequently, a study could be audited to ensure its findings were credible and applicable.

Results

This study was conducted to determine the competency requirements for healthcare professionals who work in virtual health care settings. Experts were part of a panel through three rounds of discussion to arrive at an agreement on key items.

1.1. Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the expert panel

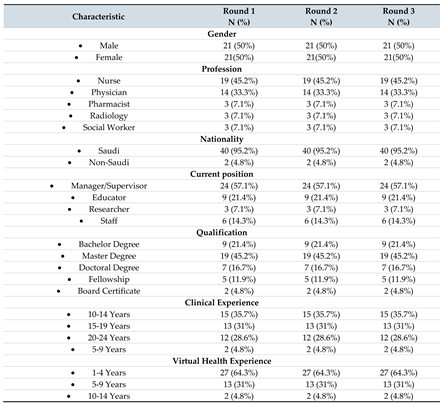

Forty-two panelists participated in all three rounds. The panelists included nurses, physicians, pharmacists, radiologists, and social workers. Most panelists (42.5%) had a Master’s degree, while 21.4% had a Bachelor’s degree. Most panelists (66.7%) had 10-19 years of clinical experience. However, only 4.8% had over ten years of experience in virtual care, with most of them (64.3%) having 1-4 years of experience.

Table 1 provides an overview of the sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the Delphi expert panel.

1.1. Delphi round 1

The first round Delphi technique questionnaire was qualitative in nature and consisted of open-ended question requesting panel members to identify knowledge, skills and attitudes for virtual health. This round was essential for the research to help initiate an initial understanding of the three aspects of competence needed by every health professional in the healthcare setting. Participants were asked to identify up to 10 competencies that healthcare professionals must have to work in virtual health. Responding to the open-ended prompt questions in Round 1, participants identified 227 types of knowledge and 121 skills that healthcare professionals should have. They also showed 72 different types of attitudes regarding virtual healthcare. After Qualitative Content Analysis, 33 domains and 157 items were generated from the panelists after reviews from research supervisor and an international experts in the field.

The response statements generated in Round 1 have been excluded from this manuscript in order to focus on the competency findings

1.1. Delphi round 2

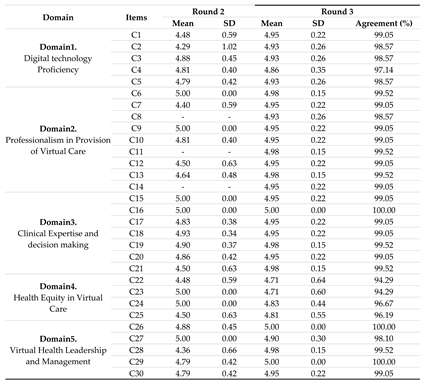

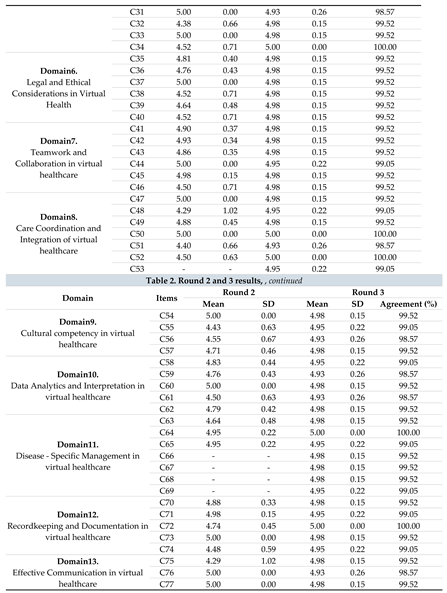

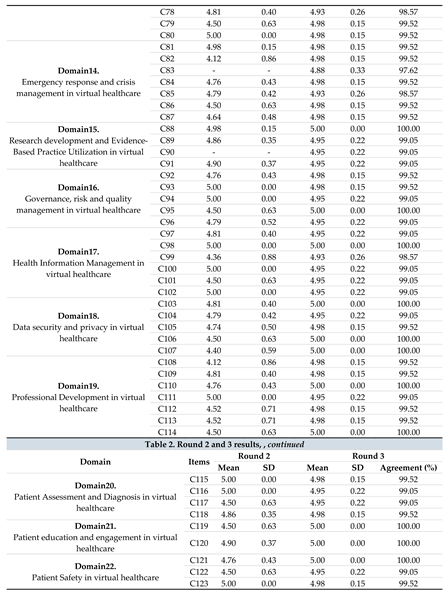

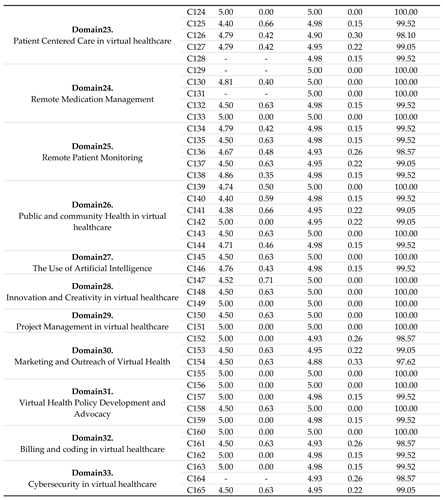

The domains and items derived from the initial questionnaire were utilized in formulating the second round Delphi questionnaire. Panel members were required to express their level of agreement or disagreement using a five-point Likert Scale for each item. Moreover, experts were asked to add items that they believed to be important for Healthcare Professionals to be competent in Virtual Health but had yet to be included in the list. The experts demonstrated strong agreement with all 33 domains items. They agreed on 157 items with a mean ≥ 4.40 and S.D. ≤ 1.02. Moreover, 14 new, non-duplicated items emerging from the open ended data were identified which is C8, C11, C14, C53, C66, C67, C68, C69, C83, C90, C128, C129, C131, C164 (

Table 2). Therefore, a list of 165 items in 33 domains was sent to 42 experts for the third survey in round 3.

1.1. Delphi round 3

In round 3, all (165) competency items reached consensus after Round 3, defined as ≥95% agreement on importance. The agreement increased from Round 2 to 3 on almost all items, indicating the Delphi process helped build consensus. For example, item C2 went from a mean of 4.29 (SD 1.02) in Round 2 to 4.93 (SD 0.26) in Round 3, with agreement increasing from 83% to 99%. Certain domains like Technology Proficiency, Professionalism, Clinical Expertise, Communication, and Teamwork had high levels of consensus (95-100% agreement) on most competencies. Other domains like Health Equity, Public Health, and Billing had more variation, with some items not reaching 95% agreement.

Table 2.

Round 2 and 3 results.

Table 2.

Round 2 and 3 results.

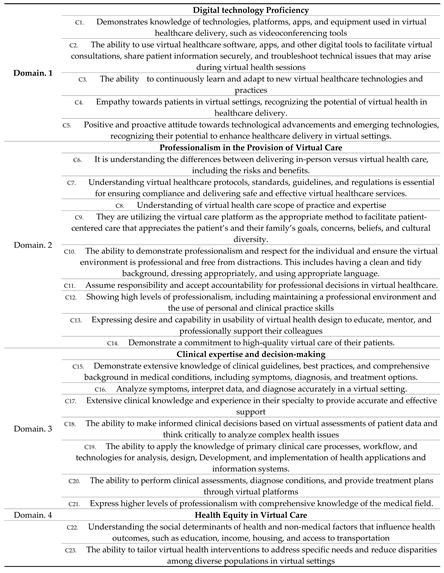

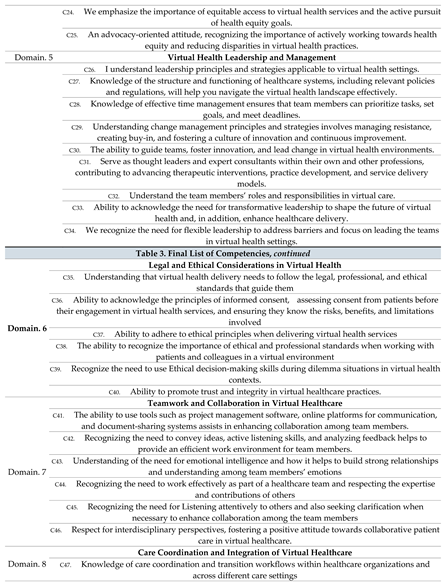

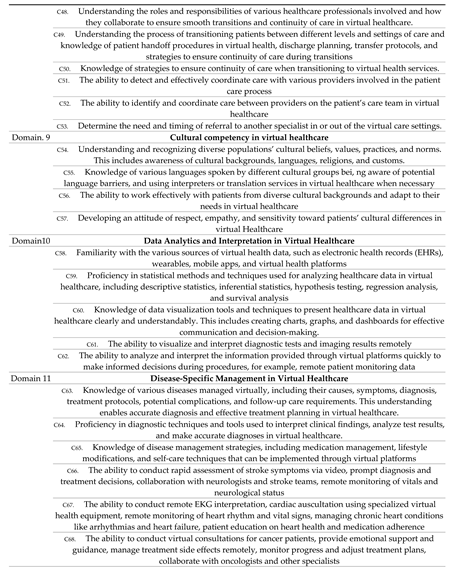

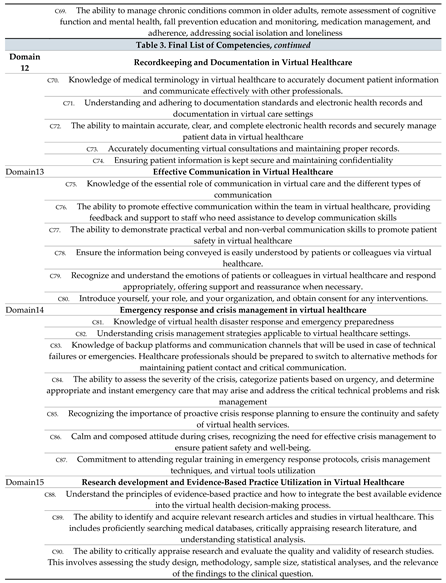

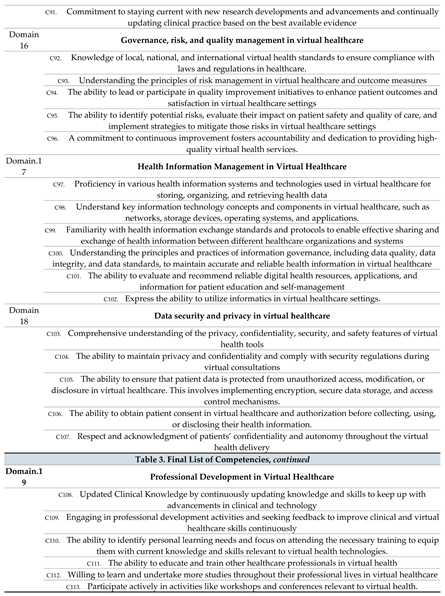

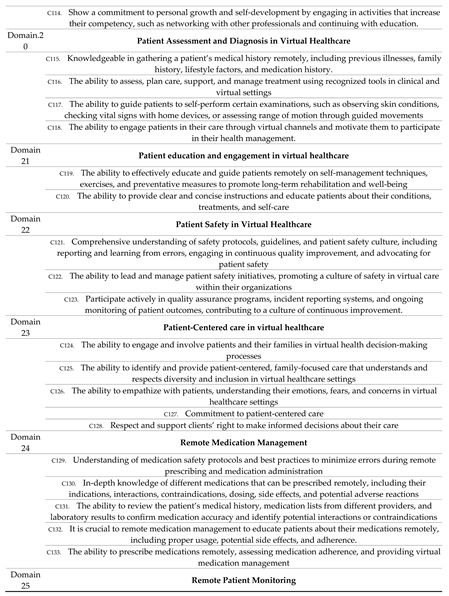

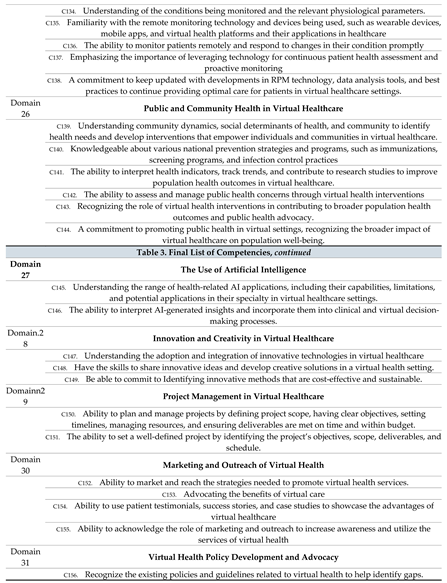

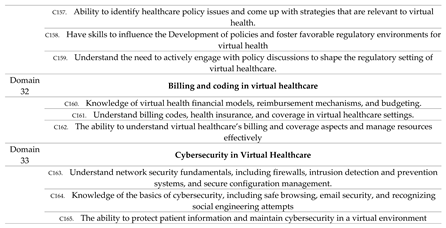

A list of 165 competencies in 33 domains was finalized as shown in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Final List of Competencies from Delphi method.

Table 3.

Final List of Competencies from Delphi method.

1.1. External validation

External reviewers were invited to validate the study’s results’ importance, relevance, and comprehensiveness. The reviewers included international experts in virtual care. The reviewers agreed that all items were adequately covered and the results are applicable in different virtual care settings.

Discussion

In this study, we established a set of competencies for health professionals in Saudi Arabia through a two-round Delphi survey, which identified a series of knowledge, skills, and other abilities essential to achieving virtual health. The consensus-based set of competencies provides the first comprehensive description of the competencies frameworks in Saudi health systems for healthcare professionals to work effectively in virtual health settings. In our study, one hundred sixty-five competencies were identified as highly important for health professionals who work on virtual health (

Table 3). The competencies had an agreement ranging from 94.29% to 100 %. This agreement was brought about by the mean and SD of round 3, where the mean went from 4-5 while the SD, on the other hand, ranged from 0.00- 0.64. In all the domains, as showcased in

Table 3, the competencies required the health professionals to understand and know the specific domain. In addition, they had to have the ability to navigate through the virtual healthcare system, including the software involved.

This study provides a framework for various stakeholders, from healthcare administrators to educators, to understand the competencies needed in an increasingly digital healthcare world. This ensures a more integrated and effective approach to virtual healthcare services, benefiting patients through improved quality and safety. While the Saudi Commission provides regulation and guidance for Health specialists and the Ministry for Health (MOH), the result from this study can be used to develop comprehensive rules and guidelines for virtual health practice in Saudi Arabia. A clear framework will ensure healthcare professionals have the competencies to deliver high-quality virtual healthcare. Moreover, one of the main goals of healthcare is to offer safe and high-quality service. Identifying the right competencies ensures that healthcare providers are well-equipped to provide this level of care, even in a virtual setting.

Virtual health development has brought rise to the need for health professionals who are skilled with the needed competencies to surpass the barriers associated with virtual healthcare and provide high-quality patient care. Digital technology proficiency in virtual Healthcare (C1-C5) and artificial intelligence ensures high-quality healthcare delivery and positive patient outcomes (Alowais et al., 2023). Without digital competence, there will be barriers to navigating telehealth systems, leading to disparities in healthcare access and outcomes (Le et al., 2023). Competencies related to professionalism (C6-C14) and ethical consideration (C35-C40) also play an important role.

When the health practitioners are both professional and have ethical considerations, Health Information Management skills (C97-C102), and Data Security and Privacy (C103-C107), then it is “guaranteed to have quality of care, sustainable costs, professional liability and respect of patient privacy, and data protection and confidentiality” (Solimini et al., 2021). Clinical expertise and decision-making (C15-C21) “healthcare providers to have the knowledge and ability to determine when virtual care is appropriate” (Curran et al., 2023). According to HRRS (2023), health equity in virtual care (C22-C25) and virtual health leadership and management (C26-C34) competencies will help health practitioners understand the role of virtual healthcare and aid in meeting the needs of marginalized communities. Professionals must also have a sense of collaboration and teamwork (C41-C46) for improved performance (Greilich et al., 2023).

Similarly, care coordination and integration of virtual Healthcare (C47-C53) are the common competencies needed for effective workflow and also to ensure that timely and coordinated care is received by patients (HealthSnap, 2023). Innovature BPO (2023) states that it is easier to make effective decisions when one has data utilization competence (C58-C62). In contrast, another cultural competency (C54-C57) allows practitioners to care for a diverse population (Hilty et al., 2020). A proper Recordkeeping and Documentation routine in Virtual Healthcare (C70-C74) is essential for ensuring safe continuity of care (Medical Protection, 2022). Recognition of diseases and their specific management (C63- C69) and Patient Safety competencies (C121- C123) guarantees that the patient’s care is safe (Kinnunen et al., 2023).

Effective Communication (C75-C80) and Emergency Response and Crisis Management (C81-C87) competencies in Virtual Healthcare are important aspects of ensuring collaborative teamwork and fostering safe patient care (Utilities One, 2023). Similarly, practitioners with Competencies in research development and evidence-based practice guarantee high-quality Healthcare outcomes (Schetaki et al., 2023). “Digital marketing will play a role in promoting telehealth services and educating patients about its benefits” (Clapp, 2023). Therefore, health practitioners need to be competent in marketing and outreach. When patients adapt to innovative technologies (C147-C149) and engage in continuous learning and Development (C108-C114), their skills are expounded and advanced, and advancement in their careers is witnessed (Team, 2023).

Practitioners with patient care assessment and diagnosis (C121-C123) and patient-centered care (C124-C128) tend to make decisions based on patient preference as they are subjected to only the patient’s needs (Kuipers et al., 2019). Project management is important because it ensures compliance with ethical and legal policies (W. Team, 2023). Remote Patient Monitoring(C134-C138) and Remote Medication Management competency (C129-C133) will reduce acute hospital events (Thomas et al., 2021). Similarly, health practitioners who can do correct billing and coding impact virtual health performance. “Incorrect billing and coding can result in denied claims or delayed and decreased payments” (Bajowala et al., 2020). According to Javaid et al. (2023), virtual health must employ cybersecurity competence in their workers for better protection of information for the patients. All the competencies of C165 are essential in ensuring that the health outcomes for patients are improved.

Recommendations and Conclusion

This study’s findings are crucial for enhancing healthcare delivery in an increasingly digitalizing world. They lay out an extensive list containing 165 competencies across 33 domains. These competencies provide a strong foundation for training, regulation, and virtual care practice in Saudi Arabia and other countries. Several key recommendations emerge from the results, as discussed below.

Virtual care competencies should be integrated into both undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula in Saudi Arabia (Kruse et al., 2021). Universities and educational institutions must prepare future healthcare professionals with knowledge and skills for virtual practice. They can achieve this objective by incorporating relevant competencies into telehealth, informatics, communication, ethics, and clinical care courses. Universities and educational institutions can use experiential learning through simulations and telehealth encounters to build the healthcare professionals’ competency (Bajra et al., 2023). For current healthcare practitioners, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties, which oversees licensing, can mandate certified virtual care training programs that teach the identified competencies. Healthcare professional associations can also design continuing medical education activities to develop virtual care competencies among their members.

The study provides a starting point for governments to develop a standardized national virtual care competency framework to guide the training and certification of healthcare professionals. Multiple stakeholders in the healthcare sector should adapt and validate the study’s findings to create nation-specific frameworks similar to those established in the United States and Canada (Scott Kruse et al., 2020). The frameworks can define competency domains, specific skills, and performance metrics. Certifications can then be offered to validate competency attainment by providers (Shaw et al., 2018).

Virtual care technologies should be designed to enable and enhance competent practice. Platforms should embed features like intuitive interfaces, clinical prompts, smart templates, and analytics dashboards. This allows providers to seamlessly apply competencies as they interact with the system (Mbunge et al., 2022; Kruse et al., 2018). Extensive training is key so that professionals maximize these functionalities for quality care delivery.

Healthcare organizations also play a critical role in competency integration. Supportive policies, incentives and culture must be cultivated to drive adoption of virtual modalities into routine practice. Policies can promote use of telehealth for communication, consultations, monitoring and team collaboration. Incentives can encourage training, certification and ongoing development. Equally important, organizational culture needs to embrace virtual care as a legitimate model of quality care, at par with traditional in-person delivery (Alaboudi et al., 2016).

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Both authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

The authors state that there is no fund received for the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consents obtained from all participating experts prior to the commencement of the Delphi study. Each participant has been provided with a detailed Informed Consent Statement, outlining the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits associated with their involvement in the research. The informed consent process was conducted transparently, with due diligence to respect the autonomy and rights of each expert involved in contributing to the comprehensive understanding of competencies in virtual healthcare.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the support provided by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University through Research Center a college of nursing. They also sincerely thank all the SEHA Virtual Hospital leaders, experts and reviewers who participated in this study.

Declaration of competing interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Ministry of Health (IRB log No: 23-26 M) and the King Saud University Institutional Review Board (No:KSU-HE-23-621). Participants were guaranteed the voluntary nature of their involvement, along with the assurance of complete anonymity and confidentiality regarding their data. Study participants who agreed to participate in the study completed an electronic informed consent form, conflict of interest, and general information form.

References

- Alaboudi, A., Atkins, A., Sharp, B., Balkhair, A., Alzahrani, M., & Sunbul, T. (2016). Barriers and challenges in adopting Saudi telemedicine network: The perceptions of decision-makers of healthcare facilities in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 9(6), 725-733. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034116301393.

- Alahmari, A., Alenazi, A., Alrabiah, A. M., Albattal, S., & Kofi, M. (2022). Patient’s Experience of the Newly Implemented Virtual Clinic during the COVID-19 Pandemic in PHCs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care Open Acc, 6, 181. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mostafa-Kofi/publication/360218497_Patients’_Experience_of_the_Newly_Implemented_Virtual_Clinic_during_the_COVID-19_Pandemic_in_PHCs_Riyadh_Saudi_Arabia/links/62691752ee24725b3ecb5511/Patients-Experience-of-the-Newly-Implemented-Virtual-Clinic-during-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-in-PHCs-Riyadh-Saudi-Arabia.pdf.

- Alharbi, K. G., Aldosari, M. N., Alhassan, A. M., Alshallal, K. A., Altamimi, A. M., & Altulaihi, B. A. (2021). Patient satisfaction with virtual clinic during Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in primary healthcare, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 28(1), 48. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7927967/.

- Al-Rayes, S., Alumran, A., Aljanoubi, H., Alkaltham, A., Alghamdi, M., & Aljabri, D. (2022, September). Awareness and Use of Virtual Clinics Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia. In Healthcare (Vol. 10, No. 10, p. 1893). MDPI. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/10/1893/pdf.

- Alowais, S. A., Alghamdi, S. S., Alsuhebany, N., Alqahtani, T., Alshaya, A. I., Almohareb, S. N., ... & Albekairy, A. M. (2023). Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC medical education, 23(1), 689. [CrossRef]

- Anil, K., Bird, A. R., Bridgman, K., Erickson, S., Freeman, J., McKinstry, C. & Abey, S. (2023). Telehealth competencies for allied health professionals: A scoping review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1357633 × 231201877. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1357633X231201877.

- Bajowala, S. S., Milosch, J., & Bansal, C. (2020). Telemedicine Pays Billing and Coding Update: Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 20(10).

- Bajra, R., Srinivasan, M., Torres, E. C., Rydel, T., & Schillinger, E. (2023). Training future clinicians in telehealth competencies: Outcomes of a telehealth curriculum and teleOSCEs at an academic medical center. Frontiers in Medicine, 10. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10577422/.

- Boulkedid, R., Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., & Alberti, C. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PloS One, 6(6), e20476. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020476&type=printable.

- Boulkedid, R., Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., & Alberti, C. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PloS One, 6(6), e20476. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020476&type=printable.

- Bunnell, B. E., Barrera, J. F., Paige, S. R., Turner, D., & Welch, B. M. (2020). Acceptability of telemedicine features to promote its uptake in practice: a survey of community telemental health providers. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(22), 8525. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/22/8525/pdf.

- Carter, E. J., Nguyen, C. N., Zlateva, I., Xia, Y., Liu, X., Bahrami, N., & Khatri, P. (2020). Patient and provider perspectives on telehealth for chronic disease management in the United States: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Informatics, 8(5), e16261. [CrossRef]

- Clapp, P. (2023, August 8). What is the role of digital marketing in the healthcare industry? Priority Pixels. Available online: https://prioritypixels.co.uk/blog/what-is-the-role-of-digital-marketing-in-the-healthcare-industry/. [CrossRef]

- Curran, V., Hollett, A., & Peddle, E. (2023). Training for virtual care: What do the experts think? 9, 20552076231179028–20552076231179028. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H., & Sulmasy, L. S. (2015). Policy recommendations to guide the use of telemedicine in primary care settings. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(10), 787-789. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26344925/.

- Ekeland, A. G., Bowes, A., & Flottorp, S. (2010). Effectiveness of telemedicine: a systematic review of reviews. International journal of medical informatics, 79(11), 736-771. Available online: https://fhi.brage.unit.no/fhi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2377962/Ekeland_011010_Eff.pdf?sequence=1.

- Fronczek, A. E., & Rouhana, N. A. (2018). Attaining mutual goals in telehealth encounters: Utilizing King’s framework for telenursing practice. Nursing Science Quarterly, 31(3), 233-236. [CrossRef]

- Greilich, P. E., Kilcullen, M., Paquette, S., Lazzara, E. H., Scielzo, S., Hernandez, J., Preble, R., Michael, M., Sadighi, M., Tannenbaum, S., Phelps, E., Hoggatt Krumwiede, K., Sendelbach, D., Rege, R., & Salas, E. (2023). Team FIRST framework: Identifying core teamwork competencies critical to interprofessional healthcare curricula. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 7(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R. P., & Suman, R. (2021). Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sensors International, 2, 100117. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666351121000383.

- Harrison, R., & Manias, E. (2022). How safe is virtual healthcare? International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 34(2), mzac021. [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D. M., Gentry, M. T., McKean, A. J., Cowan, K. E., Lim, R. F., & Lu, F. G. (2020). Telehealth for rural, diverse populations: telebehavioral and cultural competencies, clinical outcomes and administrative approaches. MHealth, 6(6), 20–20. [CrossRef]

- HealthSnap, H. (2023, December 19). How Virtual Care Management Programs Can Improve Your Clinical Workflows in 2024. Available online: https://healthsnap.io/how-virtual-care-management-programs-can-improve-your-clinical-workflows-in-2024/.

- HRRS. (2023, August 15). Health equity in telehealth | Telehealth.HHS.gov. Telehealth.hhs.gov. Available online: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/health-equity-in-telehealth.

- Innovature BPO. (2023, September 5). A Guide To Data-Driven Decision Making. Available online: https://innovatureinc.com/a-guide-to-data-driven-decision-making/.

- Javaid, D. M., Haleem, Prof. A., Singh, D. R. P., & Suman, D. R. (2023). Towards insighting Cybersecurity for Healthcare domains: A comprehensive review of recent practices and trends. Cyber Security and Applications, p. 1, 100016. [CrossRef]

- Jonasdottir, S. K., Thordardottir, I., & Jonsdottir, T. (2022). Health professionals’ perspective towards challenges and opportunities of telehealth service provision: a scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 167, 104862. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U.-M., Kuusisto, A., Koponen, S., Ahonen, O., Kaihlanen, A.-M., Hassinen, T., & Vehko, T. (2023). Nurses’ Informatics Competency Assessment of Health Information System Usage: A Cross-sectional Survey. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 41(11), 869. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C. S., Karem, P., Shifflett, K., Vegi, L., Ravi, K., & Brooks, M. (2018). Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(1), 4-12. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29320966/.

- Kruse, C. S., Williams, K., Bohls, J., & Shamsi, W. (2021). Telemedicine and health policy: a systematic review. Health Policy and Technology, 10(1), 209-229. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211883720301155.

- Kuipers, S. J., Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2019). The Importance of patient-centered Care and co-creation of Care for Satisfaction with Care and Physical and Social well-being of Patients with multi-morbidity in the Primary Care Setting. BMC Health Services Research, 19(13), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Le, T. V., Galperin, H., & Traube, D. (2023). The impact of digital competence on telehealth utilization. Health Policy and Technology, 12(1), 100724. [CrossRef]

- Longhini, J., Rossettini, G., & Palese, A. (2022). Digital health competencies among health care professionals: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(8), e36414. Available online: https://www.jmir.org/2022/8/e36414/.

- MacMullin, K., Jerry, P., & Cook, K. (2020). Psychotherapist experiences with telepsychotherapy: Pre-COVID-19 lessons for a post-COVID-19 world. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 248. Available online: https://clinica.ispa.pt/ficheiros/areas_utilizador/user40/macmullin.pdf.

- Mbunge, E., Batani, J., Gaobotse, G., & Muchemwa, B. (2022). Virtual healthcare services and digital health technologies deployed during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Africa: a systematic review. Global health journal, 6(2), 102-113. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2414644722000239.

- Medical Protection. (2022). The Importance of Good Record Keeping. Articles. Available online: https://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/articles/the-importance-of-good-record-keeping-uk.

- Ministry of Health.(2023) SEHA Virtual Hospital. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Projects/Documents/Seha-Virtual-Hospital.pdf.

- Schetaki, S., Evridiki Patelarou, Konstantinos Giakoumidakis, Christos Kleisiaris, & Athina Patelarou. (2023). Evidence-Based Practice Competency of Registered Nurses in the Greek National Health Service. Nursing Reports, 13(3), 1225–1235. [CrossRef]

- Scott Kruse, C., Karem, P., Shifflett, K., Vegi, L., Ravi, K., & Brooks, M. (2018). Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(1), 4-12. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1357633X16674087.

- Shaw, J., Jamieson, T., Agarwal, P., Griffin, B., Wong, I., & Bhatia, R. S. (2018). Virtual care policy recommendations for patient-centered primary care: Findings of a consensus policy dialogue using a nominal group technique. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(5), 298-306. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/54867866/Shaw_et_al__Virtual_care_policy_for_patient_centered_care__earlier_version_of_published_paper.pdf.

- Shariff, N. (2015). Utilizing the Delphi survey approach: A review. J Nurs Care, 4(3), 246. Available online: https://ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=eastafrica_fhs_sonam.

- Smith, A. C., Thomas, E., Snoswell, C. L., Haydon, H., Mehrotra, A., Clemensen, J., & Caffery, L. J. (2020). Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(5), 309-313. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1357633X20916567.

- Solimini, R., Busardò, F. P., Gibelli, F., Sirignano, A., & Ricci, G. (2021). Ethical and Legal Challenges of Telemedicine in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina, 57(12), 1314. [CrossRef]

- Team, H. E. (2023, October 14). The Role of Training and Development in Accelerating Healthcare Career Growth. Soft Skills for Healthcare. Available online: https://esoftskills.com/healthcare/the-role-of-training-and-development-in-accelerating-healthcare-career-growth/.

- Team, W. (2023, September 2). Healthcare Project Management for Patient-Centered Care. Blog Wrike. Available online: https://www.wrike.com/blog/optimizing-healthcare-project-management-2/#:~:text=Project%20managers%20play%20a%20crucial.

- Thomas, E. E., Taylor, M. L., Banbury, A., Snoswell, C. L., Haydon, H. M., Gallegos Rejas, V. M., Smith, A. C., & Caffery, L. J. (2021). Factors influencing the effectiveness of remote patient monitoring interventions: a realist review. BMJ Open, 11(8), e051844. [CrossRef]

- Utilities One, (2023). Communicating Emergency Response Protocols in Healthcare Systems. Utilities One. Available online: https://utilitiesone.com/communicating-emergency-response-protocols-in-healthcare-systems.

- Webster, P. (2020). Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10231), 1180-1181. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7146660/.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the expert panel.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the expert panel.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).