Submitted:

18 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

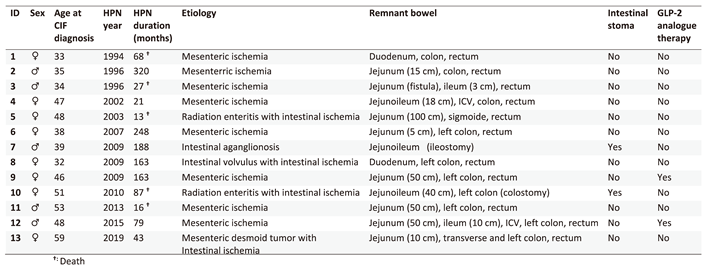

2. Materials and Methods

Patients

Patient education and training program for HPN administration

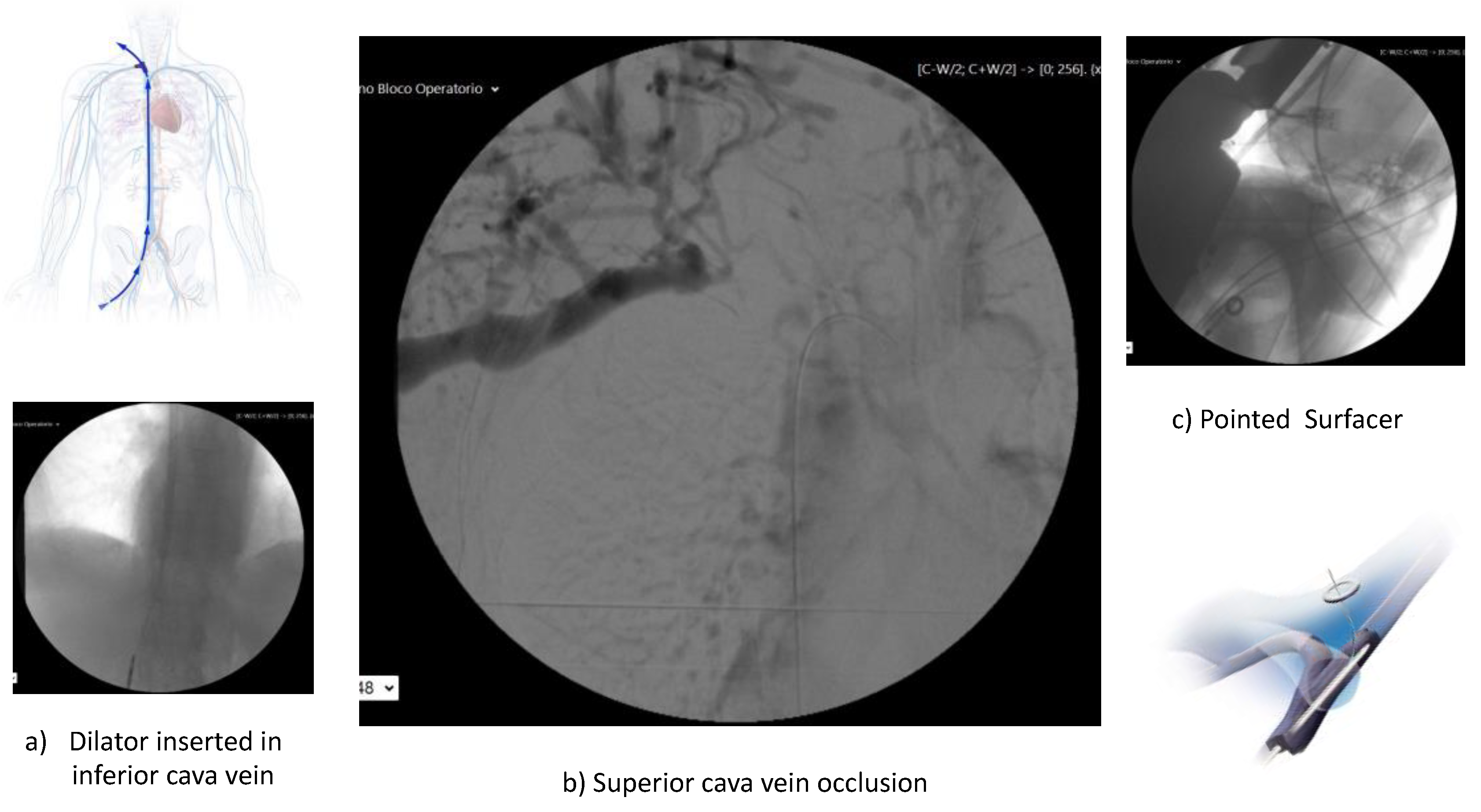

Central venous access and nutritional support

Teduglutide therapy

Culinary food support

Follow-up

3. Results

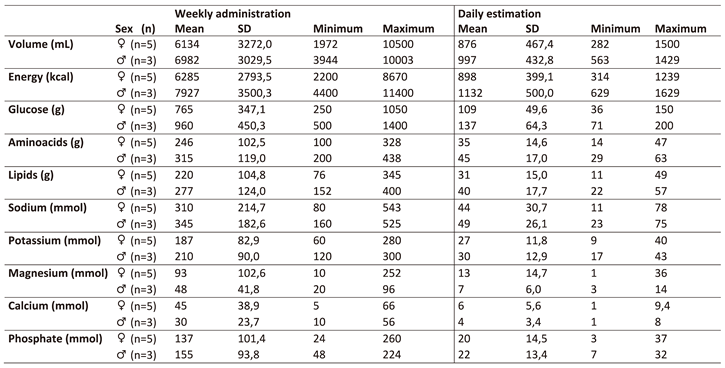

Nutritional support

Teduglutide therapy

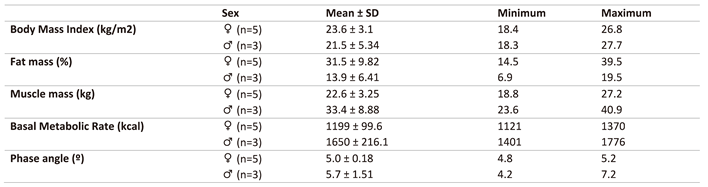

Nutritional status

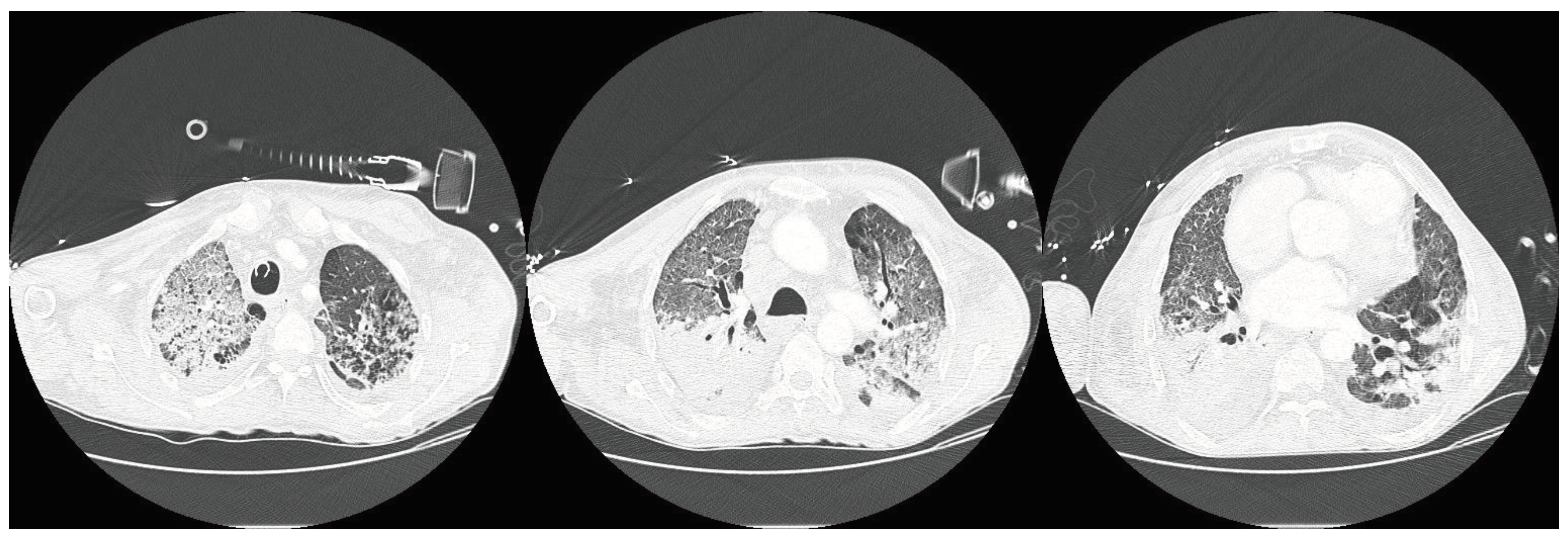

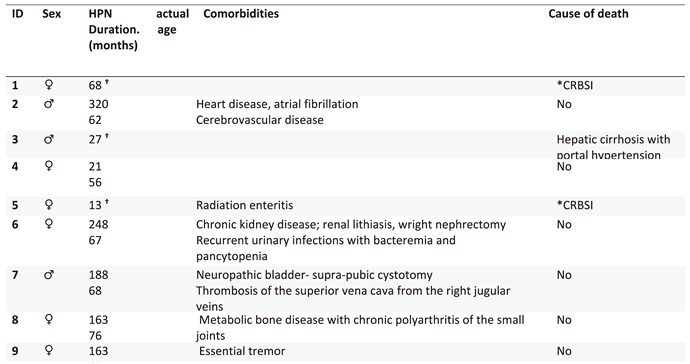

Complications related and unrelated to HPN

Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardiner, K.R. Management of acute intestinal failure. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2011, 70, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironi, L.; Cuerda, C.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Joly, F.; Jonkers, C.; Krznaric, Z.; Lal, S.; Lamprecht, G.; Lichota, M.; Mundi, M.S.; et al. ESPEN guideline on chronic intestinal failure in adults - Update 2023. Clin Nutr 2023, 42, 1940–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3. Ballesteros Pomar MD, Vidal Casariego A. [Short bowel syndrome: definition, causes, intestinal adaptation and bacterial overgrowth]. Nutricion hospitalaria : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Nutricion Parenteral y Enteral. 2007;22 Suppl 2:74-85.

- Guillen, B.; Atherton, N.S. Short Bowel Syndrome. In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL), 2021.

- D'Eusebio, C.; Merlo, F.D.; Ossola, M.; Bioletto, F.; Ippolito, M.; Locatelli, M.; De Francesco, A.; Anro, M.; Romagnoli, R.; Strignano, P.; et al. Mortality and parenteral nutrition weaning in patients with chronic intestinal failure on home parenteral nutrition: A 30-year retrospective cohort study. Nutrition 2023, 107, 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironi, L.; Boeykens, K.; Bozzetti, F.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Lal, S.; Lichota, M.; Muhlebach, S.; Van Gossum, A.; Wanten, G.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Home parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 2023, 42, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Austin, P.; Boeykens, K.; Chourdakis, M.; Cuerda, C.; Jonkers-Schuitema, C.; Lichota, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Schneider, S.M.; Stanga, Z.; et al. ESPEN guideline on home enteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 2020, 39, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.; Guerra, P.; Rocha, A.; Correia, M.; Ferreira, R.; Fonseca, J.; Lima, E.; Oliveira, A.; Gomes, M.; Ramos, D.; et al. Clinical, Economic, and Humanistic Impact of Short-Bowel Syndrome/Chronic Intestinal Failure in Portugal (PARENTERAL Study). GE Port J Gastroenterol 2022, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A. , Pereira, I., Ramalhão AM. Home total parenteral nutrition by absence of jejune and ileum (case report) [original title in portuguese: Nutrição paretérica total dominciliária por ausência de jejuno-íleo (caso clínico)]. Arquivos Portugueses de Cirurgia 1995, 4, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pironi, L.; Boeykens, K.; Bozzetti, F.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Lal, S.; Lichota, M.; Mühlebach, S.; Van Gossum, A.; Wanten, G.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Home parenteral nutrition. Clinical Nutrition 2023, 42, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshi, Z.; Yadav, S.; Salonen, B.R.; Bonnes, S.L.; Varayil, J.E.; Harmsen, W.S.; Hurt, R.T.; Tremaine, W.J.; Loftus, E.V., Jr. Incidence and Outcomes of Home Parenteral Nutrition in Patients With Crohn Disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Crohns Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, C.R.; Lal, S. Approaches to intestinal failure in Crohn's disease. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2011, 70, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, U.A.; Vrakas, G.; Reddy, S.; Baumgar, D.C.; Neuhaus, P.; Friend, P.J.; Pascher, A.; Vaidya, A. Chronic intestinal failure after crohn disease: when to perform transplantation. JAMA surgery 2014, 149, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaiselvan, R.; Theis, V.S.; Dibb, M.; Teubner, A.; Anderson, I.D.; Shaffer, J.L.; Carlson, G.L.; Lal, S. Radiation enteritis leading to intestinal failure: 1994 patient-years of experience in a national referral centre. European journal of clinical nutrition 2014, 68, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, E.; Clermont-Dejean, N.M.; Schwenger, K.J.P.; Noelting, J.; Lu, Z.; Lou, W.; Allard, J.P. Patients With Severe Gastrointestinal Dysmotility Disorders Receiving Home Parenteral Nutrition Have Similar Survival As Those With Short-Bowel Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 2021, 45, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culine, S.; Chambrier, C.; Tadmouri, A.; Senesse, P.; Seys, P.; Radji, A.; Rotarski, M.; Balian, A.; Dufour, P. Home parenteral nutrition improves quality of life and nutritional status in patients with cancer: a French observational multicentre study. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2014, 22, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcos, O.; Castier, Y.; Sibert, A.; Gaujoux, S.; Ronot, M.; Joly, F.; Paugam, C.; Bretagnol, F.; Abdel-Rehim, M.; Francis, F.; et al. Effects of a multimodal management strategy for acute mesenteric ischemia on survival and intestinal failure. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 2013, 11, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, R.J., Jr.; McGurgan, J.; Butera, L.; Poloyac, K.; Roberts, M.; Stein, W.; Minervini, M.; Jorgensen, D.R.; Humar, A. Gastrointestinal Tract Reconstruction in Adults with Ultra-Short Bowel Syndrome: Surgical and Nutritional Outcomes. Surgery 2020, 168, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibb, M.J.; Abraham, A.; Chadwick, P.R.; Shaffer, J.L.; Teubner, A.; Carlson, G.L.; Lal, S. Central Venous Catheter Salvage in Home Parenteral Nutrition Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections: Long-Term Safety and Efficacy Data. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hammou Taleb, M.H.; Mahmutovic, M.; Michot, N.; Malgras, A.; Nguyen-Thi, P.L.; Quilliot, D. Effectiveness of salvage catheters in home parenteral nutrition: A single-center study and systematic literature review. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 56, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonenberger, K.A.; Reber, E.; Huwiler, V.V.; Durig, C.; Muri, R.; Leuenberger, M.; Muhlebach, S.; Stanga, Z. Quality of Life in the Management of Home Parenteral Nutrition. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dreuille, B.; Nuzzo, A.; Bataille, J.; Mailhat, C.; Billiauws, L.; Le Gall, M.; Joly, F. Post-Marketing Use of Teduglutide in a Large Cohort of Adults with Short Bowel Syndrome-Associated Chronic Intestinal Failure: Evolution and Outcomes. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Joly, F.; Mu, F.; Kelkar, S.S.; Olivier, C.; Xie, J.; Seidner, D.L. Predictors and timing of response to teduglutide in patients with short bowel syndrome dependent on parenteral support. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 43, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Lal, S.; French, C.; Sowerbutts, A.M.; Gittins, M.; Gabe, S.; Brundrett, D.; Culkin, A.; Calvert, C.; Thompson, B.; et al. Investigating the Relationship between Home Parenteral Support and Needs-Based Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Intestinal Failure: A National Multi-Centre Longitudinal Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, P.B. New approaches to the treatments of short bowel syndrome-associated intestinal failure. Current opinion in gastroenterology 2014, 30, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, O.J. Intestinal failure-associated liver disease and the use of fish oil-based lipid emulsions. World review of nutrition and dietetics 2015, 112, 90–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandivada, P.; Chang, M.I.; Potemkin, A.K.; Carlson, S.J.; Cowan, E.; O'Loughlin A, A.; Mitchell, P.D.; Gura, K.M.; Puder, M. The Natural History of Cirrhosis From Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease After Resolution of Cholestasis With Parenteral Fish Oil Therapy. Annals of surgery 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.I.; Puder, M.; Gura, K.M. The use of fish oil lipid emulsion in the treatment of intestinal failure associated liver disease (IFALD). Nutrients 2012, 4, 1828–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawinski, M.; Bzikowska, A.; Omidi, M.; Majewska, K.; Zielinska-Borkowska, U. Liver disease in patients qualified for home parenteral nutrition - a consequence of a failure to adjust RTU bags in the primary centre? Polski przeglad chirurgiczny 2014, 86, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reber, E.; Staub, K.; Schonenberger, K.A.; Stanga, A.; Leuenberger, M.; Pichard, C.; Schuetz, P.; Muhlebach, S.; Stanga, Z. Management of Home Parenteral Nutrition: Complications and Survival. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 2021, 77, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelting, J.; Gramlich, L.; Whittaker, S.; Armstrong, D.; Marliss, E.; Jurewitsch, B.; Raman, M.; Duerksen, D.R.; Stevenson, D.; Lou, W.; et al. Survival of Patients With Short-Bowel Syndrome on Home Parenteral Nutrition: A Prospective Cohort Study. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 2021, 45, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joly, F.; Baxter, J.; Staun, M.; Kelly, D.G.; Hwa, Y.L.; Corcos, O.; De Francesco, A.; Agostini, F.; Klek, S.; Santarpia, L.; et al. Five-year survival and causes of death in patients on home parenteral nutrition for severe chronic and benign intestinal failure. Clin Nutr 2018, 37, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibb, M.; Soop, M.; Teubner, A.; Shaffer, J.; Abraham, A.; Carlson, G.; Lal, S. Survival and nutritional dependence on home parenteral nutrition: Three decades of experience from a single referral centre. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).