# Equally contributed as last authors

1. Introduction

Since early 2020, the world has been fighting with COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019), the respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The virus belongs to the coronaviridae subfamily, more specifically in the

Betacoronavirus genera and has a positive-sense single-stranded RNA [

5,

6,

7].

The first cases of COVID-19 date back to late 2019 in the city of Wuhan (Hubei Province, China), but the origin of the virus is still unknown, although it’s thought of as a natural evolution from an animal host to a human one. In favor of this theory is the fact that the first cases were linked to the Seafood Wholesale Market, where live animals were sold [

7,

8]. From the first cases until 18 October 2023 were registered 696,695,527 cases worldwide with 6,927,179 resulting in death [

9], while in Italy were registered 26,168,412 cases with 192,013 deaths [

10]. The transmission of the virus primarily occurs through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or breathes. These droplets can be inhaled by people nearby or can contaminate surfaces, where they can survive for several hours or even days [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Subsequently, SARS-CoV-2 through different mechanisms (mostly connected with the spike protein), can cause different clinical pictures: from asymptomatic to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Multi Organ Injury [

14].

Like any other virus, the coronavirus tends to mutate [

15,

16,

17]. During the spreading of the infection, several variants of the virus have emerged, further complicating the management of the pandemic. Each SARS-CoV-2 variant differs from the original strain due to these mutations, which can affect the virus transmissibility, the disease severity, and the immune response [

18]. Recently a group of authors published a study, which demonstrates that isolation measures during the pandemic drove faster and more transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants [

19]. With the outbreak of new variants, WHO experts, created a classification that divided the variants into different groups. The two most important are the VOCs (variants of concern) and the VOIs (variants of interest) [

20]. At this moment, there are no variants that meet VOC criteria [

21].

Of the many previous VOCs are the Delta variant (B.1.617.2), which originated in India and the Omicron variant originated in South Africa and was first identified in November 2021. The Delta variant has been associated with high transmissibility and has rapidly spread in many countries. The increased transmissibility has led to a significant rise in cases and posed an additional challenge to healthcare systems worldwide [

15,

16,

17]. The Omicron variant on the other side was less associated with severe disease but had an increased transmissibility. One of the main concerns regarding the Omicron variant is its high genetic mutability. It carries a significant number of mutations in its genetic material, particularly in the spike protein gene that the virus uses to enter human cells. Among these, some are similar to those found in other variants of concern such as Beta, Gamma, and Delta. However, the combination and widespread presence of these mutations are what make the Omicron variant unique and raise doubts about its potential ability to evade immunity [

22].

Currently, there is little data available on Omicron’s predictability regarding mortality and morbidity. As was previously done for other COVID-19 variants [

23,

24,

25,

26], we previously analyzed specific COVID-19 biomarkers from routine blood tests conducted on COVID-19 omicron patients at the emergency section level [

23,

25]. In this study [

25], we have demonstrated that troponin-T (TnT), fibrinogen (FBG), glycemia, C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), albumin, D-dimer, myoglobin (MGB), and ferritin for both men and women may predict, already at the level of the emergency section, lethal outcomes. Compared to previous Delta COVID-19 parallel emergency patterns of prediction in the

emergency room, we discussed that Omicron-induced changes in TnT and albumin may be considered early predictors of severe outcomes. In this cohort of patients, we showed that the main percentage of unvaccinated women was in the

deceased group [

25]. We also showed an LDH potentiation in unvaccinatepatientsnt. Surprisingly, vaccinated patients had higher TnT values when compared to unvaccinated individuals. As for the COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness against Omicron, in this cohort of patients we did disclose that primary immunization with more than two doses significantly increased protection.

Thus, the main aim and novelty of this study was to investigate in the same cohort of patients the “classical” routine blood biomarkers for correlating these data with the severity of their outcomes. We gathered data from 445 COVID-19 clinical records from the Emergency Room of “Policlinico Umberto I”, at the University Hospital of Sapienza University of Rome. According to their outcome, the 445 patients were divided into four groups: (1) the emergency group (patients with mild forms who were quickly discharged); (2) the hospital ward group (patients who after admission to the emergency section were hospitalized in a COVID-19 ward); (3) the intensive care unit (ICU) group (patients that after the admission in the emergency section required intensive assistance); (4) the deceased group (patients that after the admission in the emergency section had a fatal outcome).

In this study, in particular, we analyzed the possible correlation between creatinine, azotemia, blood urea nitrogen, red blood cells (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red blood cell distribution width (RDW), monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets (PLT), and plateletcrit (PCT), and the outcome of the patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants’ Selection and Study Design

This retrospective study is based on the clinical records of 445 COVID-19 patients who accessed the emergency unit of the Sapienza University Hospital “Policlinico Umberto I” of Rome, Italy, from February 1st, 2022, to March 31th, 2022. Of the 445 patients, 130 (29.2%) were not vaccinated.

We divided the patients into four groups according to their outcome (

Figure 1). Starting from the first one and going to the last, the outcome worsens:

The first group (180, M=76; F=104), also called the “emergency group” included those patients who entered the emergency room and were discharged shortly after because they did not show severe symptoms

The second group (205, M=105; F=100), also called the “hospital ward group, ward in the text and figures” included those patients admitted to the emergency room and then transferred to a COVID ward and afterward, dismissed.

The third group (25, M=14; F=11), or the “ICU group” included those, who after the admission to the hospital ward, were transferred to the COVID intensive care units and survived (ICU group).

In the fourth group (35, M=23; F=12), some patients had a fatal outcome (in the emergency room, in the hospital ward, or the ICU). We called this group the “deceased group”.

The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was based on a positive result from real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal-swab specimens. Patients who tested positive for the molecular test during recovery were transferred to the hospital’s COVID-19 wards.

The University Hospital ethical committee approved this retrospective study (Ref. 6536) and all the study procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983, for human rights and experimentation.

2.1. Participants’ Selection and Study Design

For each eligible patient, we extracted information from their medical records, such the demographic characteristics (age and sex), vaccination, symptoms, comorbidities, and laboratory analytical results. The results of the available laboratory tests were collected when patients were initially admitted to the

emergency unit.

Table 1 shows the considered analyses and the number of patients analyzed for each test concerning the total of subjects in the four groups.

2.2. Laboratory Examination

The patients' peripheral blood was collected in BD vacutainer® tubes for blood testing at the entrance of the hospital ward. The additives present in vacutainers were EDTA or sodium citrate as anticoagulants and separating gel for serum samples. Coagulation parameters were analyzed with a BCS XP System automatic hemostasis analyzer (Siemens Healthcare, Germany). PLT (reference range: 150 -450.103/μL), RBC (reference range number 3.5 - 5.1.106/μL for women, 4.3-5.9 10.6/μL for men ) and WBC (reference range: 4.4 - 11.3 10.3/μL). PCT and Hb (reference range: 12.2- 15.3 g/dL for women and 13.5-16.5 g/dL for men) were determined using ADVIA 2120i Hematology System (Siemens Healthcare, Germany). Serum biomarkers (azotemia and creatinine) were measured by standard colorimetric and enzymatic methods on a Cobas C 501 analyzer with reagents supplied by Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

According to methods previously described [

27,

28], data were analyzed to assess normality by Pearson's chi-squared test. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (

emergency vs

ward vs

ICU vs

deceased and men vs women) was used to analyze the laboratory parameters and the vaccination data. Post-hoc comparisons were carried out by using Tukey’s HSD test. The Spearman Correlation test was used to investigate the correlation between the laboratory data and the age of the patients [

29]. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to measure the diagnostic/predictive accuracy of each variable [

27]. All analyses were performed using Epitools by Ausvet (Australia) and StatView (Abacus Corporation, USA).

3. Results

We gathered all patients’ COVID-19 manifestations and their clinical conditions from the clinical records of the emergency room. All data, divided into each group and sex, are shown in

Table 2.

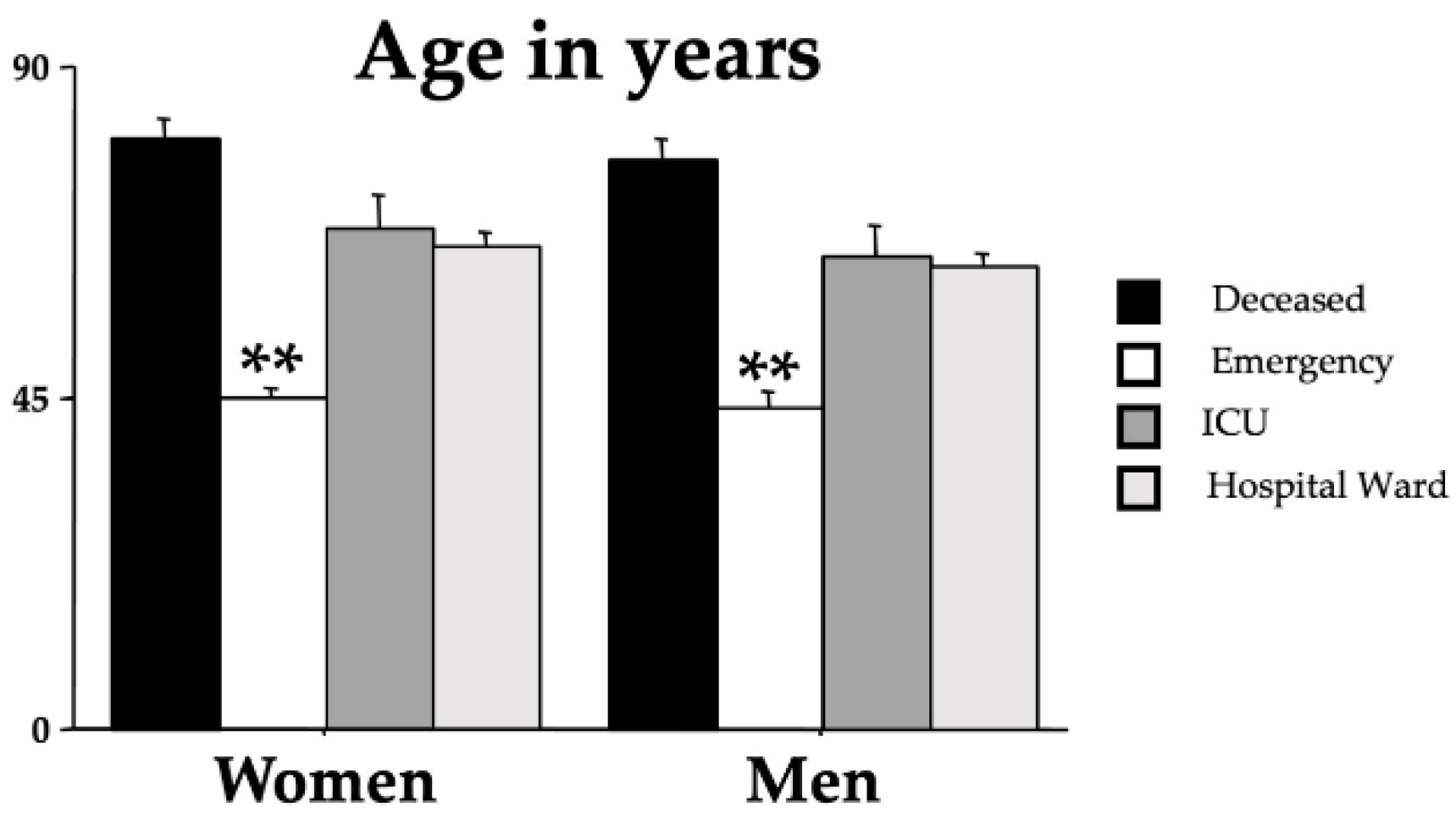

ANOVA analyses were performed to assess differences in age and sex of the different outcome groups.

Figure 2 shows the influence of age on the outcomes [F(3,437)=62.82, p<0.001]. Indeed, younger patients had a more favorable outcome while there was no sex effect on the outcome [F(1,437)=1.18, p=0.277). No interaction outcome x sex was also disclosed [F(3,437)=0.11, p=0.951].

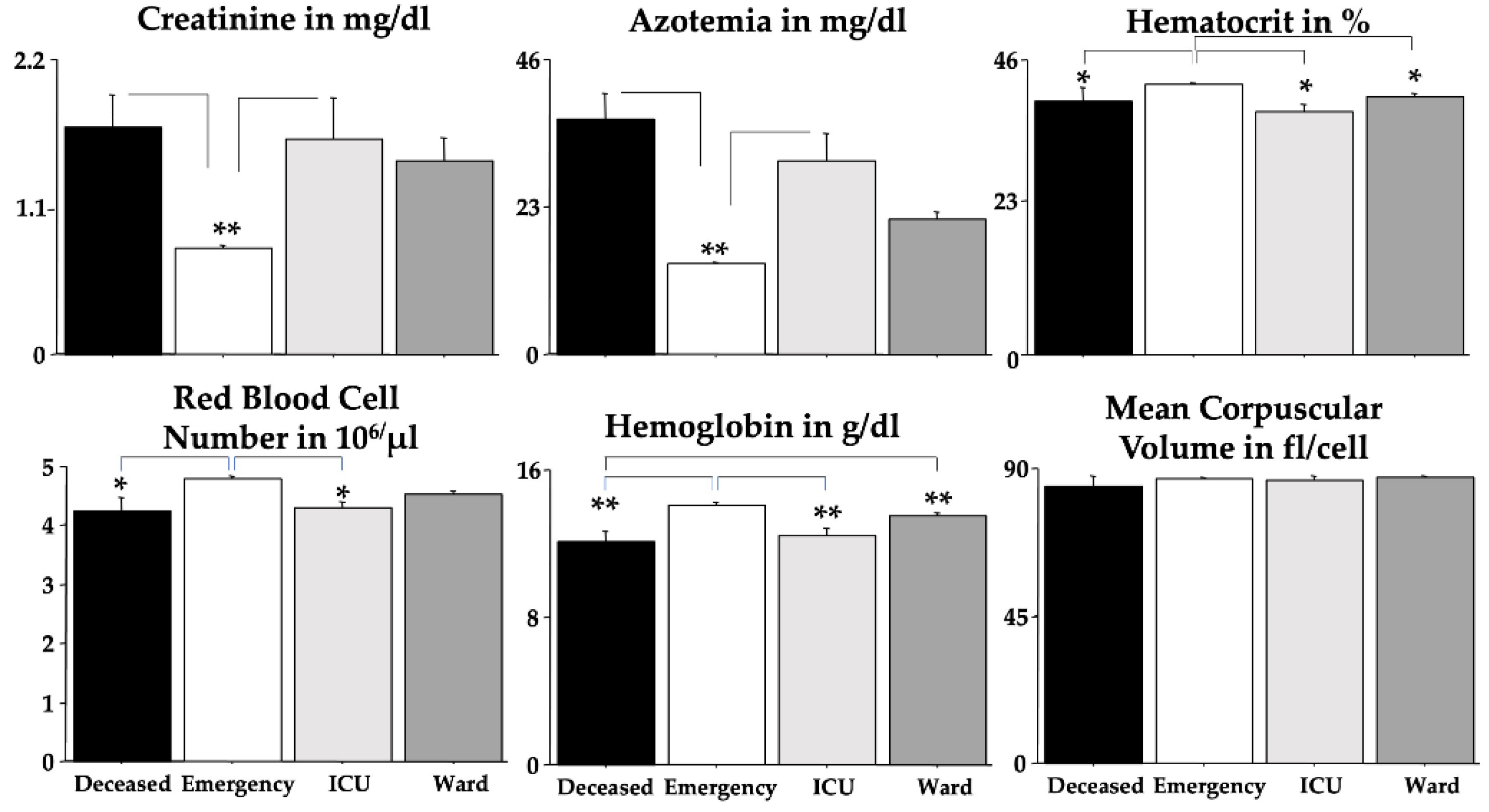

Each blood parameter was analyzed by using an ANOVA test for each group (

Table 3).

Figure 3 shows these findings but without the sex effect. We found significant elevations due to severe outcomes in creatinine, azotemia, RDW and basophils but significant diminutions in RBC, Hb, Hct and MCHC when compared to the

emergency group. Post-hoc comparisons are shown in the figures as asterisks and lines.

As expected, for RBC, Hb, and Hct, we found significant differences between men and women (

Table 3); unexpectedly, we found a sex-linked difference in PLT. ANOVA disclosed statistical interactions between “outcomes” and “sexes” for MCV and MCHC. Quite interestingly, no differences between outcomes were revealed for MCH, MCV, eosinophils, lymphocytes, neutrophils, PCT, PLT, and WBC.

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the ROC data for creatinine, azotemia, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT. The area under the curve (AUC) scores for creatinine, azotemia and RDW unveiled the highest values (in bold in

Table 4) in the deceased group.

The positive predictive values (PPV) in the

deceased, ICU, and

hospital ward groups and the negative predictive values (NPV) in the

emergency group based on the reference range values for creatinine, azotemia, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT are shown in

Table 5. In the

deceased group, the highest PPV scores were shown for the eosinophils (in bold in the table). No significant PPV scores were found for both the

ICU and

ward groups. Quite surprisingly, the NPV significant scores (in bold in the table) of the

emergency group were found for all the analyzed blood parameters but not for creatinine, RBC (both men and women), PCT, lymphocytes, and, as expected for eosinophils.

Table 6 shows the Spearman correlations for the blood biomarkers and the patients’ outcomes. As expected, significant correlations (in bold in the table) were revealed for creatinine, azotemia, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCHC, RDW, eosinophils, lymphocytes and PLT. However, no significant correlations were found for MCV, MCH, monocytes, basophils, WBC, neutrophils and PCT.

To disclose whether or not the age effect could have impacted the blood parameters of the patients with the worst outcome, we provided further Spearman correlations but only for the

deceased group (shown in

Table 7). Indeed, quite interestingly, positive correlations were found only for WBC and neutrophils but not for lymphocytes. No correlations in

deceased men or women were also found for RBC, HB, HCT and PLT, blood parameters with significant sex effects in the ANOVA (see

Table 3).

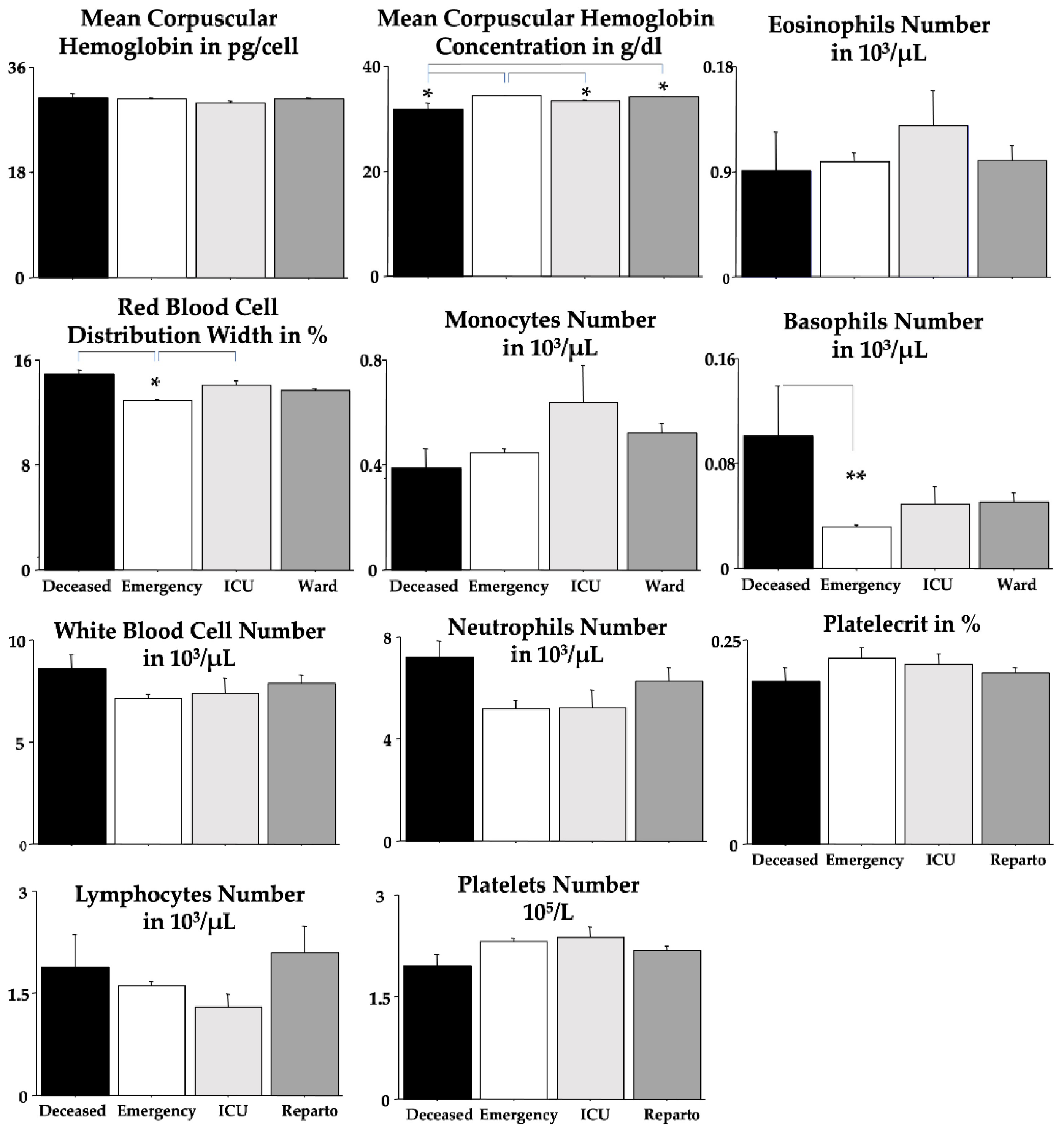

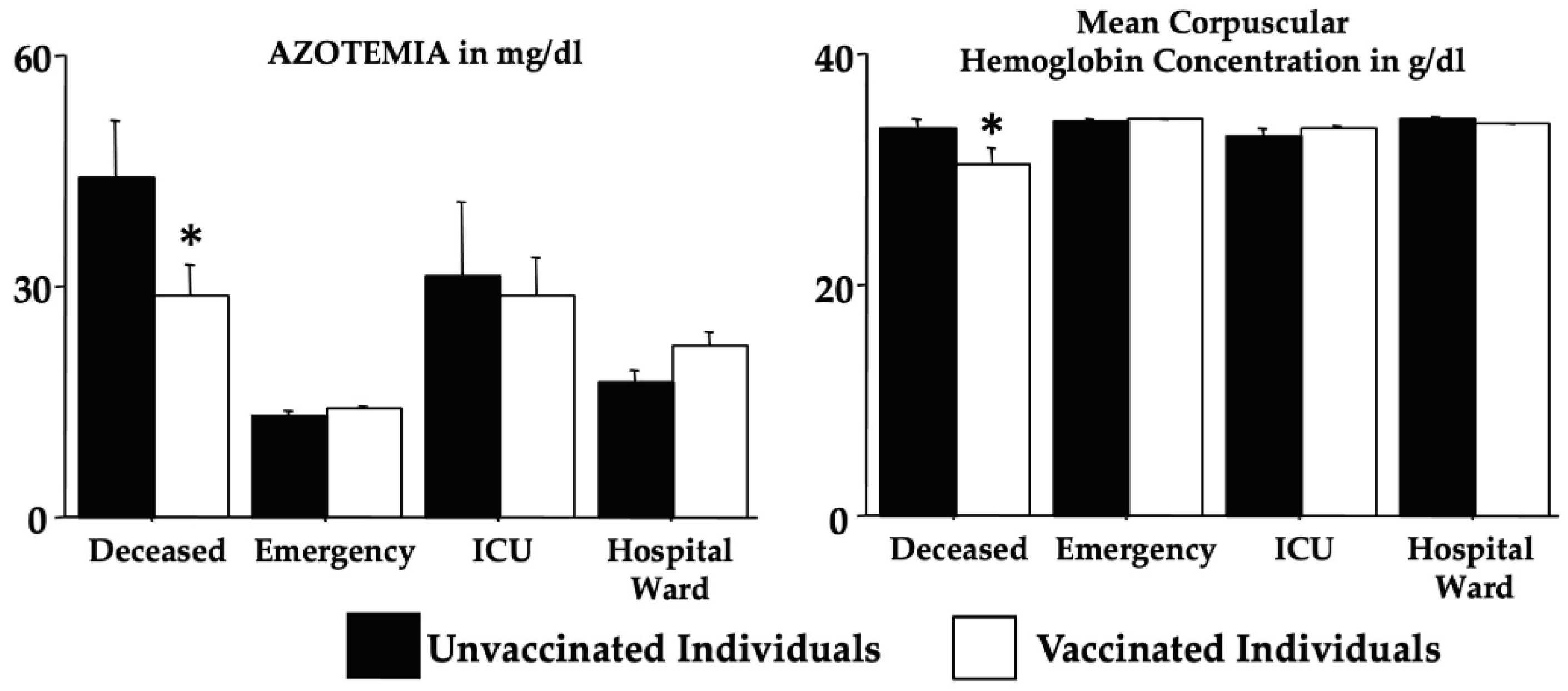

Table 8 shows the vaccination effects by two-way ANOVA (in the absence of a sex effect) on the selected analyzed blood biomarkers. Data revealed an interaction Omicron morbidity x vaccination for the creatinine, azotemia, Hb, MCV, MCH, and MCHC due to differences between groups and an effect of vaccination for MCHC (

deceased,

emergency,

ICU and

ward x vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals - please see F, dF and p on

Table 8). Notably,

Figure 4 shows the post-hoc comparisons according to the mortality for azotemia and MCHC. Indeed, for azotemia, vaccination in the individuals of the

deceased group appears to counteract the marked elevation whereas for MCHC, vaccination appears to aggravate the condition (both compared to the individuals of the

emergency group).

4. Discussion

In this retrospective research on Omicron COVID-19 patients, we show for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, that by analyzing the routine blood analyses normally carried out on the patients attending the emergency room of the Sapienza University Hospital of Rome, some routine blood parameters could have provided early reliable information on the Omicron COVID-19 outcome.

We indeed disclosed early common blood data in a cohort of 445 patients who experienced different Omicron outcomes, i.e., facing a fatal fate, or attending the ICU but surviving or attending a hospital ward or only the emergency room. According to this group differentiation (emergency vs ward vs ICU vs deceased), we evaluated the Omicron patients’ clinical records who entered the emergency unit.

The patients of the emergency group were then discharged since they did not display severe symptoms and signs. The patients of the ward group attended the dedicated COVID-19 hospital room to be soon released without significant concerns. Regrettably, other Omicron COVID-19 patients (of the ICU and deceased groups) experienced more severe infection effects with or without a lethal outcome.

We did find that Omicron COVID-19 patients who later developed a deadly outcome had early gross changes in routine blood analyses. Indeed, ANOVA investigations showed that creatinine, azotemia, RDW, and basophils were strongly potentiated in deceased Omicron COVID-19 patients if compared to the emergency group. By contrast, RBC, Hb, Hct and MCHC values were markedly decreased in deceased Omicron COVID-19 patients if compared to the patients of the emergency group. ROC data obtained by emergency room blood routine analyses extended these findings indicating that changes in creatinine, azotemia and RDW could be considered as early indicators of severe Omicron COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, PPV data showed also that striking changes in blood basophils presence could indicate plain Omicron COVID-19 morbidity and mortality whereas blood values inside normality ranges for azotemia, Hb (for both men and women), Hct, MCV, MCHC, RDW monocytes, basophils, WBC, neutrophils and PLT do represent a non-severe Omicron COVID-19 morbidity.

We also found that vaccination could have influenced in the individuals of the deceased group the levels of azotemia and MCHC but with quite different trending.

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has brought about significant changes in various aspects of healthcare. Among these, routine blood analyses have faced notable implementations and new patterns of interpretation. Routine blood analyses played a crucial role in revealing alterations that prompted the clinicians to consider the possibility of a COVID-19 infection. The original insurgence of COVID-19 has been, indeed, associated with various hematological abnormalities [

30,

31,

32]. Patients with severe infections often exhibit lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased levels of inflammatory markers. Moreover, the virus is known to induce a hypercoagulable state, leading to an increased risk of thromboembolic events [

33,

34,

35]. Abnormal clotting parameters may be observed in routine blood tests, necessitating careful monitoring and intervention to prevent complications.

The emergence of the Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has raised other, but minor, concerns globally due to its high transmissibility and potential impact on public health [

36,

37]. As for the Omicron-induced hematological changes, one of the consistent findings in individuals infected with the Omicron variant is notable alterations in lymphocyte and PLT counts [

38,

39]. Lymphocytes play a crucial role in the body's immune response, and their reduction may indicate the severity of the infection or the impact of the variant on immune cell populations [

38,

39].

Further, data suggests also that platelet counts may be affected by the Omicron variant [

38,

39]. Thrombocytopenia (reduced platelet levels) or thrombocytosis (elevated platelet levels) could occur, necessitating careful monitoring and management to address potential complications related to blood clotting [

40,

41,

42].

Our patients showed mild neutrophilia and generally conserved lymphocyte count. The interesting fact is that the lymphopenia is accentuated in the

ICU group while the

deceased group tends to have a normal count, but greater than the

emergency group. Perhaps these differences are a result of the evolution of the virus [

43,

44].

Through this study, we confirm and extend what also was previously known for non-Omicron-COVID-19 [

45]. The platelet count can, indeed, discriminate between patients who will undergo a more severe illness, especially the ones that will not survive the disease, compared with patients with a mild course.

Previous studies showed that eosinophil count was reduced in COVID-19 patients and afterward restored to normal if the patient improved, while continuing to decrease in those without an improvement [

46]. By contrast, our study didn’t register a marked eosinophil reduction but

ICU patients had a peak in eosinophil count. We do suggest that also this modification is due to COVID-19 variants and a possible Omicron peculiar characteristic [

43,

44].

Also, the count of basophils is normally decreased in COVID-19 patients [

47]. Also, our patients showed a similar trend. The interesting finding we found was a difference between the

deceased group and the other groups. Even though inside the normality range, we found a marked difference between the patients with the worse outcome compared to the ones with the best outcome.

Even though the COVID-19 emergency has finished, SARS-CoV-2 continues to infect and replicate. In doing so, it still poses a threat to the health systems around the world. Nowadays, both people and scientific community alerts are lower, mainly because the mortality has drastically reduced; nonetheless, every day, people still die from COVID-19 [

15]. Alterations in the complete blood count are known to be present in patients with COVID-19 [

48,

49], but relatively only a few studies investigated the possibility of identifying these alterations as prognostic factors

The strength of this study lies in the classification of Omicron COVID-19 individuals according to their outcomes. The present retrospective investigation is focused on the levels of

(i) blood biochemical parameters especially cellular parameters with

(ii) the aim to early predict severe COVID-19 outcomes by comparing four different groups of Omicron patients. To disclose severe outcomes, analogous investigations were carried out, but with groups of patients and other experimental schedules. Typically, the main criteria previously used were oxygen saturation levels, fever, age, respiratory rate, respiratory distress, the presence of bilateral and peripheral ground-glass opacities, and arterial blood oxygen partial pressure [

50,

51,

52].

This work has, of course, limitations. Many factors can influence the outcome of COVID-19 patients, starting from genetic predisposition to individual lifestyles to pre-existent disease conditions of the recruited patients. An important limiting factor is the scarce information about the patients’ vaccination status. In our previous work, we showed how difficult it was to get clear information about the number of vaccinations, timing, and type of vaccination in an emergency section setting [

25]. Furthermore, a confounding factor on the immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection in the number of previous infections, which was non assessed. In addition, assembling broad and complete pieces of information in the emergency section of the medical records was difficult and complex because, due to COVID-19, the hospital facilities were under pressure. For this reason, many biomedical findings are missing.

5. Conclusions

The effects of the Omicron and the other COVID-19 variants on routine blood analyses are still under investigation, and ongoing research is essential to comprehensively understand the full spectrum of hematological and biochemical changes associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants. Healthcare professionals must remain vigilant in monitoring these parameters to tailor appropriate interventions and provide optimal care for individuals affected by Omicron COVID-19. Furthermore, the effects of COVID-19 on routine blood analyses are multifaceted, encompassing direct impacts on hematological and coagulation parameters, changes in patient behavior, and alterations in healthcare delivery. As the situation is still evolving, adaptation of diagnostic practices is essential to ensure the continued effectiveness of routine blood analyses in providing valuable insights into patient health.

In conclusion, this research is a further step in the challenge to extricate early biomolecular markers of COVID-19 development. Moreover, it could also be beneficial for reports dealing with human disorders provoked by viral or bacterial infections, including other coronaviruses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R., C.B., L.T. and M.F.; investigation, E.R., G.F., L.M., F.P. (Fiorenza Pennacchia), W.A.R. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R., M.L., A.M., G.F. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, E.R., M.L., A.M., G.F. and M.F.; visualization, M.A.Z., P.P., G.T., G.B., L.M., G.G., F.P. (Francesco Pugliese), M.R.C. and L.T.; supervision, M.A.Z., C.B., A.M., L.M., G.F. and M.F.; project administration, C.B., A.M., G.G., F.P. (Francesco Pugliese), G.F. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The University Hospital Ethical Committee approved this retrospective study (Ref. 6536), and all the study procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983, for human rights and experimentation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable since this is a retrospective paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the IBBC-CNR and the Sapienza University of Rome in Rome, Italy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21:195–210. [CrossRef]

- Aliyu AA. Public health ethics and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Afr Med 2021;20:157–63. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui S, Alhamdi HWS, Alghamdi HA. Recent Chronology of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Heal 2022;10:778037. [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic n.d. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19.

- Llanes A, Restrepo CM, Caballero Z, Rajeev S, Kennedy MA, Lleonart R. Betacoronavirus genomes: How genomic information has been used to deal with past outbreaks and the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1–28. [CrossRef]

- Rabaan AA, Al-Ahmed SH, Haque S, Sah R, Tiwari R, Malik YS, et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV: A comparative overview. Infez Med 2020;28:174–84.

- Yang H, Rao Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:685–700. [CrossRef]

- Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:141–54. [CrossRef]

- COVID - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer n.d. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- Italy COVID - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer n.d. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/italy/.

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc 2020;324:782–93. [CrossRef]

- Umakanthan S, Sahu P, Ranade A V, Bukelo MM, Rao JS, Abrahao-Machado LF, et al. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad Med J 2020;96:753–8. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Ahmad Farouk I, Lal SK. COVID-19: A Review on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Evolution, Transmission, Detection, Control and Prevention. Viruses 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Harrison AG, Lin T, Wang P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Pathogenesis. Trends Immunol 2020;41:1100–15. [CrossRef]

- Hillary VE, Ceasar SA. An update on COVID-19: SARS-CoV-2 variants, antiviral drugs, and vaccines. Heliyon 2023;9:e13952. [CrossRef]

- Firouzabadi N, Ghasemiyeh P, Moradishooli F, Mohammadi-Samani S. Update on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines on different variants of SARS-CoV-2. Int Immunopharmacol 2023;117:109968. [CrossRef]

- Martín Sánchez FJ, Martínez-Sellés M, Molero García JM, Moreno Guillén S, Rodríguez-Artalejo FJ, Ruiz-Galiana J, et al. Insights for COVID-19 in 2023. Rev Esp Quimioter 2023;36:114–24. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Q, Inchakalody VP, Merhi M, Mestiri S, Taib N, Moustafa Abo El-Ella D, et al. Emerging COVID-19 variants and their impact on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, therapeutics and vaccines. Ann Med 2022;54:524–40. [CrossRef]

- Sunagawa J, Park H, Kim KS, Komorizono R, Choi S, Ramirez Torres L, et al. Isolation may select for earlier and higher peak viral load but shorter duration in SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Nat Commun 2023;14:7395. [CrossRef]

- Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants n.d. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants.

- SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 19 January 2024 n.d. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern.

- Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, Webster HH, Flaxman S, Andrews N, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet 2022;399:1303–12. [CrossRef]

- Ceci FM, Fiore M, Gavaruzzi F, Angeloni A, Lucarelli M, Scagnolari C, et al. Early Routine Biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 Morbidity and Mortality: Outcomes from an Emergency Section. Diagnostics 2022;12:176. [CrossRef]

- Gabanella F, Barbato C, Corbi N, Fiore M, Petrella C, de Vincentiis M, et al. Exploring Mitochondrial Localization of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by Padlock Assay: A Pilot Study in Human Placenta. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Pennacchia F, Rusi E, Ruqa WA, Zingaropoli MA, Pasculli P, Talarico G, et al. Blood Biomarkers from the Emergency Department Disclose Severe Omicron COVID-19-Associated Outcomes. Microorganisms 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Petrella C, Zingaropoli MA, Ceci FM, Pasculli P, Latronico T, Liuzzi GM, et al. COVID-19 Affects Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Neurofilament Light Chain in Aged Men: Implications for Morbidity and Mortality. Cells 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Payán-Pernía S, Gómez Pérez L, Remacha Sevilla ÁF, Sierra Gil J, Novelli Canales S. Absolute Lymphocytes, Ferritin, C-Reactive Protein, and Lactate Dehydrogenase Predict Early Invasive Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19. Lab Med 2021;52:141–5. [CrossRef]

- Ceccanti M, Coriale G, Hamilton DA, Carito V, Coccurello R, Scalese B, et al. Virtual Morris task responses in individuals in an abstinence phase from alcohol. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2018;96:128–36. [CrossRef]

- Fiore M, Korf J, Antonelli A, Talamini L, Aloe L. Long-lasting effects of prenatal MAM treatment on water maze performance in rats: Associations with altered brain development and neurotrophin levels. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2002;24:179–91. [CrossRef]

- Hadid T, Kafri Z, Al-Katib A. Coagulation and anticoagulation in COVID-19. Blood Rev 2021;47:100761. [CrossRef]

- Asakura H, Ogawa H. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int J Hematol 2021;113:45–57. [CrossRef]

- Wool GD, Miller JL. The Impact of COVID-19 Disease on Platelets and Coagulation. Pathobiology 2021;88:15–27. [CrossRef]

- Ponti G, Maccaferri M, Ruini C, Tomasi A, Ozben T. Biomarkers associated with COVID-19 disease progression. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2020;57:389–99. [CrossRef]

- Altmann DM, Whettlock EM, Liu S, Arachchillage DJ, Boyton RJ. The immunology of long COVID. Nat Rev Immunol 2023;23:618–34. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Dagna L, Martinod K, Dixon DL, Van Tassell BW, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2021;21:319–29. [CrossRef]

- Araf Y, Akter F, Tang Y dong, Fatemi R, Parvez MSA, Zheng C, et al. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. J Med Virol 2022;94:1825–32. [CrossRef]

- Ren S-Y, Wang W-B, Gao R-D, Zhou A-M. Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutation, infectivity, transmission, and vaccine resistance. World J Clin Cases 2022;10:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Si G, Lu H, Zhang W, Zheng S, Huang Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant clearance delayed in breakthrough cases with elevated fasting blood glucose. Virol J 2022;19:148. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhang M, Wu X, Li X, Hao X, Xu L, et al. Platelet-albumin-bilirubin score and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predict intensive care unit admission in patients with end-stage kidney disease infected with the Omicron variant of COVID-19: a single-center prospective cohort study. Ren Fail 2023;45:2199097. [CrossRef]

- Qiu W, Shi Q, Chen F, Wu Q, Yu X, Xiong L. The derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio can be the predictor of prognosis for COVID-19 Omicron BA.2 infected patients. Front Immunol 2022;13:1065345. [CrossRef]

- Wei T, Li J, Cheng Z, Jiang L, Zhang J, Wang H, et al. Hematological characteristics of COVID-19 patients with fever infected by the Omicron variant in Shanghai: A retrospective cohort study in China. J Clin Lab Anal 2023;37:e24808. [CrossRef]

- Battaglini D, Lopes-Pacheco M, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Pelosi P, Rocco PRM. Laboratory Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis in COVID-19. Front Immunol 2022;13:857573. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha LB, Foster C, Rawlinson W, Tedla N, Bull RA. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: Implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev Med Virol 2022;32:e2381. [CrossRef]

- Roemer C, Sheward DJ, Hisner R, Gueli F, Sakaguchi H, Frohberg N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution in the Omicron era. Nat Microbiol 2023;8:1952–9. [CrossRef]

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta 2020;506:145–8. [CrossRef]

- Mu T, Yi Z, Wang M, Wang J, Zhang C, Chen H, et al. Expression of eosinophil in peripheral blood of patients with COVID-19 and its clinical significance. J Clin Lab Anal 2021;35:e23620. [CrossRef]

- Kazancioglu S, Bastug A, Ozbay BO, Kemirtlek N, Bodur H. The Role of Hematological Parameters in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Influenza Virus Infection. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:e272. [CrossRef]

- Ceci FM, Ferraguti G, Lucarelli M, Angeloni A, Bonci E, Petrella C, et al. Investigating Biomarkers for COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality. Curr Top Med Chem 2023;23:1196–210. [CrossRef]

- Palladino M. Complete blood count alterations in covid-19 patients: A narrative review. Biochem Medica 2021;31:30501. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2021.030501.

- Lin S, Mao W, Zou Q, Lu S, Zheng S. Associations between hematological parameters and disease severity in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Lab Anal 2021;35. [CrossRef]

- Garrafa E, Vezzoli M, Ravanelli M, Farina D, Borghesi A, Calza S, et al. Early prediction of in-hospital death of covid-19 patients: A machine-learning model based on age, blood analyses, and chest x-ray score. Elife 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Gorgojo-Galindo Ó, Martín-Fernández M, Peñarrubia-Ponce MJ, Álvarez FJ, Ortega-Loubon C, Gonzalo-Benito H, et al. Predictive modeling of poor outcome in severe covid-19: A single-center observational study based on clinical, cytokine and laboratory profiles. J Clin Med 2021;10. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Participants flow diagram according to their outcome.

Figure 1.

Participants flow diagram according to their outcome.

Figure 2.

Mean age in years of the recruited individuals for each group divided by sex. The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisks (** p < 0.01) indicate the post-hoc differences between the emergency group and all the other groups.

Figure 2.

Mean age in years of the recruited individuals for each group divided by sex. The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisks (** p < 0.01) indicate the post-hoc differences between the emergency group and all the other groups.

Figure 3.

Blood parameters were analyzed by using ANOVA. The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisks (** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05) indicate post-hoc differences between groups.

Figure 3.

Blood parameters were analyzed by using ANOVA. The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisks (** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05) indicate post-hoc differences between groups.

Figure 4.

Vaccination effects on azotemia and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (see

Table 8). The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisk (* p < 0.05) indicates post hoc differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals of the

deceased group.

Figure 4.

Vaccination effects on azotemia and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (see

Table 8). The error bars indicate pooled standard error means (SEM) derived from the appropriate error mean square in the ANOVA. The asterisk (* p < 0.05) indicates post hoc differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals of the

deceased group.

Table 1.

The number of routine analyses available for each group and considered for the statistical analyses.

Table 1.

The number of routine analyses available for each group and considered for the statistical analyses.

| |

Emergency |

Hospital Ward |

ICU |

Deceased |

| N. of patients |

180 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Creatinine |

171 |

179 |

23 |

31 |

| Azotemia |

160 |

179 |

23 |

31 |

| Red Blood Cells (RBC) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Hematocrit (Hct) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Red Blood Cell Distribution Width (RDW) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Monocytes |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Eosinophils |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Basophils |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| White Blood Cells (WBC) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Neutrophils |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Lymphocytes |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Platelets (PLT) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

| Platelecrit (PCT) |

178 |

205 |

25 |

35 |

Table 2.

Recorded symptoms and comorbidities characterizing the recruited individuals for each group.

Table 2.

Recorded symptoms and comorbidities characterizing the recruited individuals for each group.

| |

Emergency |

Hospital Ward |

ICU |

Deceased |

| M (76) |

F (104) |

M (105) |

F (100) |

M (14) |

F (11) |

M (23) |

F (12) |

| COVID-19 symptoms |

| Fever |

30 (39.47%) |

58 (55.77%) |

55 (52.38%) |

43 (43.00%) |

5 (35.71%) |

5 (45.45%) |

11 (47.83%) |

7 (58.33%) |

| Cough |

26 (34.21%) |

48 (46.15%) |

36 (34.29%) |

28 (28.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

2 (18.18%) |

8 (34.78%) |

3 (25.00%) |

| Dyspnea |

14 (18.42%) |

30 (28.85%) |

42 (40.00%) |

31 (31.00%) |

6 (42.86%) |

6 (54.55%) |

15 (65.22%) |

9 (75.00%) |

| Asthenia |

10 (13.16%) |

23 (22.12%) |

8 (7.62%) |

12 (12.00%) |

2 (14.29%) |

3 (27.27%) |

3 (13.04%) |

2 (16.67%) |

| Rhinitis |

6 (7.89%) |

5 (4.81%) |

6 (5.71%) |

2 (2.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Memory deficits |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.95%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (4.35%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Vertigo |

2 (2.63%) |

3 (2.88%) |

0 (0.00%) |

4 (4.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Anosmia |

1 (1.32%) |

2 (1.92%) |

1 (0.95%) |

4 (4.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Ageusia |

1 (1.32%) |

2 (1.92%) |

1 (0.95%) |

2 (2.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Depression or anxiety |

3 (3.95%) |

2 (1.92%) |

1 (0.95%) |

4 (4.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Brain fog |

1 (1.32%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.95%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (4.35%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Epistaxis |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.95%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Arthralgia or myalgia |

12 (15.79%) |

32 (30.77%) |

7 (6.67%) |

7 (7.00%) |

2 (14.29%) |

1 (9.09%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (16.67%) |

| Headache |

8 (10.53%) |

14 (13.46%) |

6 (5.71%) |

9 (9.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (9.09%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Paresthesia |

3 (3.95%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (2.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Sore throat |

11 (14.47%) |

4 (3.85%) |

6 (5.71%) |

8 (8.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Comorbidities |

| Lung diseases |

8 (10.53%) |

11 (10.58%) |

12 (11.43%) |

21 (21.00%) |

4 (28.57%) |

3 (27.27%) |

2 (8.70%) |

2 (16.67%) |

| Cardiac diseases |

15 (19.74%) |

22 (21.15%) |

54 (51.43%) |

54 (54.00%) |

9 (64.29%) |

6 (54.55%) |

16 (69.57%) |

10 (83.33%) |

| Dyslipidemia |

2 (2.63%) |

2 (1.92%) |

11 (10.48%) |

9 (9.00%) |

2 (14.29% |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (4.35%) |

1 (8.33%) |

| Chronic Renal Failure |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (1.92%) |

11 (10.48%) |

11 (11.00%) |

2 (14.29% |

1 (9.09%) |

6 (26.09%) |

2 (16.67%) |

| Oncological diseases |

3 (3.95%) |

12 (11.54%) |

13 (12.38% |

15 (15.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

2 (18.18%) |

9 (39.13%) |

3 (2500%) |

| Diabetes |

2 (2.63%) |

2 (1.92%) |

19 (18.10%) |

18 (18.00%) |

3 (21.43%) |

2 (18.18%) |

3 (13.04%) |

2 (16.67%) |

| Gastrointestinal diseases |

9 (11.84%) |

8 (7.69%) |

11 (10.48%) |

10 (10.00%) |

4 (28.57%) |

2 (18.18%) |

4 (17.39%) |

3 (25.00%) |

| Neurological or psychiatric diseases |

5 (6.58%) |

12 (11.54%) |

15 (14.29%) |

22 (22.00%) |

3 (21.43% |

6 (54.55%) |

8 (34.78%) |

4 (33.33%) |

| Urologic diseases |

5 (6.58%) |

5 (4.81%) |

8 (7.62%) |

5 (5.00%) |

3 (21.43% |

1 (9.09%) |

6 (26.09%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Ophthalmological diseases |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.96%) |

3 (2.86%) |

3 (3.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

| Immunological, rheumatological or hematological diseases |

7 (9.21%) |

19 (18.27%) |

16 (15.24%) |

14 (14.00%) |

1 (7.14%) |

0 (0.00%) |

4 (17.39%) |

2 (16.67%) |

Table 3.

ANOVA data of the studied blood parameters for the four groups. p-value ≤ 0.05 are shown in bold.

Table 3.

ANOVA data of the studied blood parameters for the four groups. p-value ≤ 0.05 are shown in bold.

| Omicron COVID-19 Effect |

|---|

| |

dF |

F-Value |

p-Value |

|

dF |

F-Value |

p-Value |

| Creatinine |

|

|

|

Monocytes |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

5.500 |

0.0010 |

Outcome |

3 |

2.626 |

0.0500 |

| Sex |

1 |

0.011 |

0.9178 |

Sex |

1 |

0.060 |

0.8063 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.265 |

0.8510 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.486 |

0.6921 |

| Azotemia |

|

|

|

Eosinophils |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

26.175 |

<0.0001 |

Outcome |

3 |

0.212 |

0.8881 |

| Sex |

1 |

0.756 |

0.3852 |

Sex |

1 |

0.002 |

0.9690 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

2.278 |

0.0792 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

1.550 |

0.2008 |

| Red Blood Cells |

|

|

|

Basophils |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

11.878 |

<0.0001 |

Outcome |

3 |

3.883 |

0.0093 |

| Sex |

1 |

7.523 |

0.0063 |

Sex |

1 |

3.125 |

0.0778 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.886 |

0.4483 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.1936 |

0.1936 |

| Hemoglobin |

|

|

|

White Blood Cells |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

15.505 |

<0.0001 |

Outcome |

3 |

1.323 |

0.2662 |

| Sex |

1 |

8.502 |

0.0037 |

Sex |

1 |

0.521 |

0.4708 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.1759 |

0.1759 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.400 |

0.7534 |

| Hematocrit |

|

|

|

Neutrophils |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

7.957 |

<0.0001 |

Outcome |

3 |

1.587 |

0.1918 |

| Sex |

1 |

11.825 |

0.0006 |

Sex |

1 |

1.013 |

0.3147 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.908 |

0.4372 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.198 |

0.8975 |

| MCV |

|

|

|

Lymphocytes |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

0.434 |

0.7291 |

Outcome |

3 |

0.721 |

0.5400 |

| Sex |

1 |

3.698 |

0.0551 |

Sex |

1 |

0.003 |

0.9581 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

4.356 |

0.0049 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

0.105 |

0.9572 |

| MCH |

|

|

|

Platelets |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

0.734 |

0.5320 |

Outcome |

3 |

2.041 |

0.1075 |

| Sex |

1 |

0.027 |

0.8688 |

Sex |

1 |

5.742 |

0.0170 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

2.057 |

0.1053 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

1.994 |

0.1142 |

| MCHC |

|

|

|

Platelecrit |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

11.367 |

<0.0001 |

Outcome |

3 |

0.593 |

0.6201 |

| Sex |

1 |

0.046 |

0.8299 |

Sex |

1 |

3.057 |

0.811 |

| Outcome x Sex |

3 |

4.426 |

0.0044 |

Outcome x Sex |

3 |

1.560 |

4.681 |

| RDW |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Outcome |

3 |

16.817 |

<0.0001 |

|

|

|

|

| Sex |

1 |

4.079E-4 |

0.9839 |

|

|

|

|

| Outcome*Sex |

3 |

0.508 |

06772 |

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

AUC scores for the creatinine, azotemia, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT. The highest scores were found for creatinine, azotemia and RDW in the deceased group when compared with the patients of the emergency. Significant scores are shown in bold.

Table 4.

AUC scores for the creatinine, azotemia, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT. The highest scores were found for creatinine, azotemia and RDW in the deceased group when compared with the patients of the emergency. Significant scores are shown in bold.

| |

Deceased VS Emergency

|

ICU VS Emergency

|

| |

AUC (Area under the curve) |

95% Confidence Interval |

AUC (Area under the curve) |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Creatinine |

0.814 |

0.719-0.909 |

0.699 |

0.573-0.824 |

| Azotemia |

0.837 |

0.728-0.945 |

0.757 |

0.622-0.893 |

| RBC |

0.748 |

0.639-0.857 |

0.761 |

0.668-0.854 |

| Hb |

0.738 |

0.631-0.844 |

0.764 |

0.656-0.873 |

| Hct |

0.712 |

0.596-0.828 |

0.752 |

0.631-0.872 |

| MCV |

0.479 |

0.356-0.603 |

0.53 |

0.393-0.667 |

| MCH |

0.467 |

0.338-0.595 |

0.616 |

0.494-0.737 |

| MCHC |

0.683 |

0.579-0.788 |

0.701 |

0.587-0.815 |

| RDW |

0.872 |

0.798-0.946 |

0.745 |

0.614-0.876 |

| Monocytes |

0.671 |

0.548-0.793 |

0.55 |

0.405-0.695 |

| Eosinophils |

0.707 |

0.594-0.821 |

0.548 |

0.42-0.676 |

| Basophils |

0.509 |

0.381-0.637 |

0.485 |

0.344-0.627 |

| WBC |

0.608 |

0.49-0.726 |

0.482 |

0.331-0.633 |

| Neutrophils |

0.704 |

0.6-0.809 |

0.518 |

0.362-0.674 |

| Lymphocytes |

0.666 |

0.56-0.772 |

0.625 |

0.503-0.748 |

| PLT |

0.685 |

0.58-0.79 |

0.531 |

0.396-0.665 |

| PCT |

0.624 |

0.517-0.732 |

0.53 |

0.395-0.664 |

Table 5.

Positive predictive values (PPV—probability that the patient has the condition when restricted to those patients who tested positive) in the deceased, ICU and hospital ward groups and negative predictive values (NPV—probability that a patient who has a negative test result indeed does not have the condition) in the emergency group are based on the reference range values (out of range for PPV; in range for NPV) creatinine, azotemia, RBC (men and women), Hb (men and women), Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT. Significant scores are shown in bold.

Table 5.

Positive predictive values (PPV—probability that the patient has the condition when restricted to those patients who tested positive) in the deceased, ICU and hospital ward groups and negative predictive values (NPV—probability that a patient who has a negative test result indeed does not have the condition) in the emergency group are based on the reference range values (out of range for PPV; in range for NPV) creatinine, azotemia, RBC (men and women), Hb (men and women), Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT and PCT. Significant scores are shown in bold.

| |

PPV

Deceased

|

PPV

ICU

|

PPV

Ward

|

NPV

Emergency

|

| Creatinine (0.8 - 1.2 mg/dl) |

0.581 |

0.565 |

0.503 |

0.538 |

| Azotemia (7 - 22 mg/dl) |

0.742 |

0.478 |

0.246 |

0.919 |

RBC

(Men 4.7 - 6.1·106/µL)

(Women 4.2 - 5.4·106/µL) |

0.783

0.583 |

0.714

0.545 |

0.495

0.300 |

0.760

0.765 |

Hb

(Men 14 - 18g/dl)

(Women 12 - 16g/dl) |

0.739

0.333 |

0.643

0.455 |

0.495

0.270 |

0.893

0.893

|

| Hct (38 - 52%) |

0.629 |

0.560 |

0.332 |

0.820 |

| MCV (80 - 100 fl/cell) |

0.257 |

0.080 |

0.078 |

0.904 |

| MCH (27 - 33 pg/cell) |

0.400 |

0.080 |

0.161 |

0.856 |

| MCHC (32 - 36 g/dl) |

0.371 |

0.160 |

0.176 |

0.906 |

| RDW (11.6% - 14.6%) |

0.531 |

0.400 |

0.200 |

0.928 |

| Monocytes (0.2 - 0.6·103/µL) |

0.486 |

0.440 |

0.332 |

0.811 |

| Eosinophils (0.1 - 0.5·103/µL) |

0.914 |

0.577 |

0.737 |

0.383 |

| Basophils (0 - 0.3·103/µL) |

0.086 |

0.000 |

0.044 |

1.000 |

| WBC (4.4 - 11.3·103/µL) |

0.343 |

0.320 |

0.293 |

0.839 |

| Neutrophils (1.8 - 7.7·103/µL) |

0.429 |

0.440 |

0.229 |

0.883 |

| Lymphocytes (1.0 - 4.8·103/µL) |

0.743 |

0.440 |

0.498 |

0.711 |

| PLT (1.5 - 4.0 ·105/L) |

0.286 |

0.160 |

0.244 |

0.861 |

| PCT (0.12 - 0.36%) |

0.743 |

0.480 |

0.593 |

0.539 |

Table 6.

Spearman correlation values for the blood biomarkers and the patients’ outcome. Significant values are shown in bold.

Table 6.

Spearman correlation values for the blood biomarkers and the patients’ outcome. Significant values are shown in bold.

| Spearman’s Correlation |

|---|

| |

Spearman’s rho |

p-value |

| Creatinine |

0.295 |

< .001 |

| Azotemia |

0.364 |

< .001 |

| RBC |

-0.253 |

< .001 |

| Hb |

-0.237 |

< .001 |

| Hct |

-0.256 |

< .001 |

| MCV |

0.023 |

0.632 |

| MCH |

-0.011 |

0.823 |

| MCHC |

-0.175 |

< .001 |

| RDW |

0.335 |

< .001 |

| Monocytes |

-0.035 |

0.458 |

| Eosinophils |

-0.177 |

< .001 |

| Basophils |

-0,071 |

0.134 |

| WBC |

0.051 |

0.287 |

| Neutrophils |

0.102 |

0.032 |

| Lymphocytes |

-0.225 |

< .001 |

| PLT |

-0.132 |

< .005 |

| PCT |

-0.086 |

0.069 |

Table 7.

Spearman correlations for the age parameter in the deceased group only. Significant values are shown in bold.

Table 7.

Spearman correlations for the age parameter in the deceased group only. Significant values are shown in bold.

| Spearman’s Correlation |

|---|

| |

Spearman’s rho |

p-value |

| Creatinine |

-0.095 |

0.602 |

| Azotemia |

0.268 |

0.141 |

| RBC |

men -0.154

women -0.098

|

men 0.469

women 0.735 |

| Hb |

men 0.021

women -0.444 |

men 0.923

women 0.124 |

| Hct |

men -0.056

women -0.254

|

men 0.791

women 0.378 |

| MCV |

0.091 |

0.595 |

| MCH |

0.062 |

0.716 |

| MCHC |

-0.126 |

0.464 |

| RDW |

0.244 |

0.174 |

| Monocytes |

0.140 |

0.414 |

| Eosinophils |

0.220 |

0.200 |

| Basophils |

0.109 |

0.536 |

| WBC |

0.526 |

0.002 |

| Neutrophils |

0.421 |

0.014 |

| Lymphocytes |

0.163 |

0.343 |

| PLT |

men 0.043

women -0.319

|

men 0.841

women 0.269 |

| PCT |

0.036 |

0.835 |

Table 8.

The effects of vaccination on the analyzed biomarkers in a two-way ANOVA. The sex effect was not considered because not significant. Significant scores are shown in bold.

Table 8.

The effects of vaccination on the analyzed biomarkers in a two-way ANOVA. The sex effect was not considered because not significant. Significant scores are shown in bold.

| Omicron COVID-19 and Vaccination Effects |

|---|

| |

Vaccination (Yes/No) |

Outcome |

Vaccination x Outcome |

| |

dF |

F-Value |

p-Value |

dF |

F-value |

p-Value |

dF |

F-Value |

p-Value |

| Creatinine |

1 |

2.235 |

0.1358 |

3 |

3.675 |

0.0123 |

3 |

1.175 |

0.3189 |

| Azotemia |

1 |

1.775 |

0.1836 |

3 |

24.347 |

<0.0001 |

3 |

4.521 |

0.0039 |

| Red Blood Cells |

1 |

3.199 |

0.0744 |

3 |

7.573 |

<0.0001 |

3 |

0.449 |

0.7180 |

| Hemoglobin |

1 |

2.847 |

0,0922 |

3 |

10.767 |

<0.0001 |

3 |

3.900 |

0.0091 |

| Hematocrit |

1 |

0.005 |

0.9427 |

3 |

3.963 |

0.0083 |

3 |

0.994 |

0.3955 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume |

1 |

0.049 |

0.8243 |

3 |

1.502 |

0.2133 |

3 |

4.559 |

0.0037 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin |

1 |

0.659 |

0.4172 |

3 |

1.698 |

0.1666 |

3 |

2.937 |

0.331 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration |

1 |

5.478 |

0.0197 |

3 |

13.598 |

<0.0001 |

3 |

7.725 |

<0.0001 |

| Red Distribution Width |

1 |

0.652 |

0.4199 |

3 |

15.820 |

<0.0001 |

3 |

0.380 |

0.7675 |

| Monocytes |

1 |

2.987 |

0.0846 |

3 |

1.553 |

0.2001 |

3 |

0.556 |

0.6446 |

| Eosinophils |

1 |

1.141 |

0.2861 |

3 |

0.480 |

0.6962 |

3 |

0.775 |

0.5086 |

| Basophils |

1 |

0.77 |

0.7809 |

3 |

5.646 |

0.0008 |

3 |

0.155 |

0.9263 |

| White Blood Cells |

1 |

2.893 |

0.0897 |

3 |

1.058 |

0.3668 |

3 |

0.737 |

0.5303 |

| Neutrophils |

1 |

1.686 |

0.1949 |

3 |

1.351 |

0.2574 |

3 |

0.173 |

0.9149 |

| Lymphocytes |

1 |

1.134 |

0.2876 |

3 |

0.415 |

0.7423 |

3 |

0.299 |

0.8258 |

| Platelets |

1 |

0.362 |

0.5476 |

3 |

1.168 |

0.3214 |

3 |

0.841 |

0.4718 |

| Plateletcrit |

1 |

0.135 |

0.7134 |

3 |

0.165 |

0.9197 |

3 |

0.835 |

0.4754 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).