Submitted:

21 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

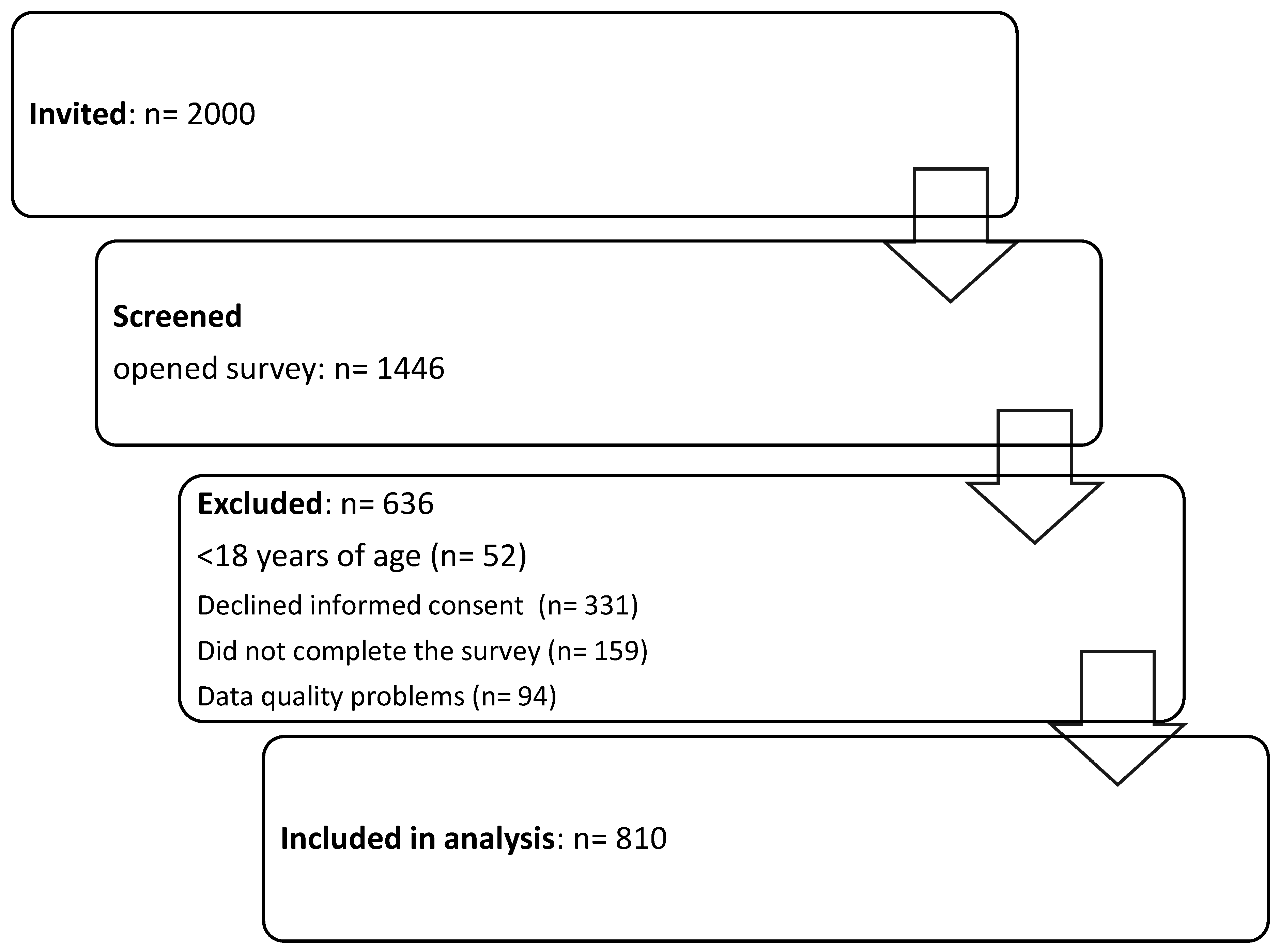

2. Materials and Methods

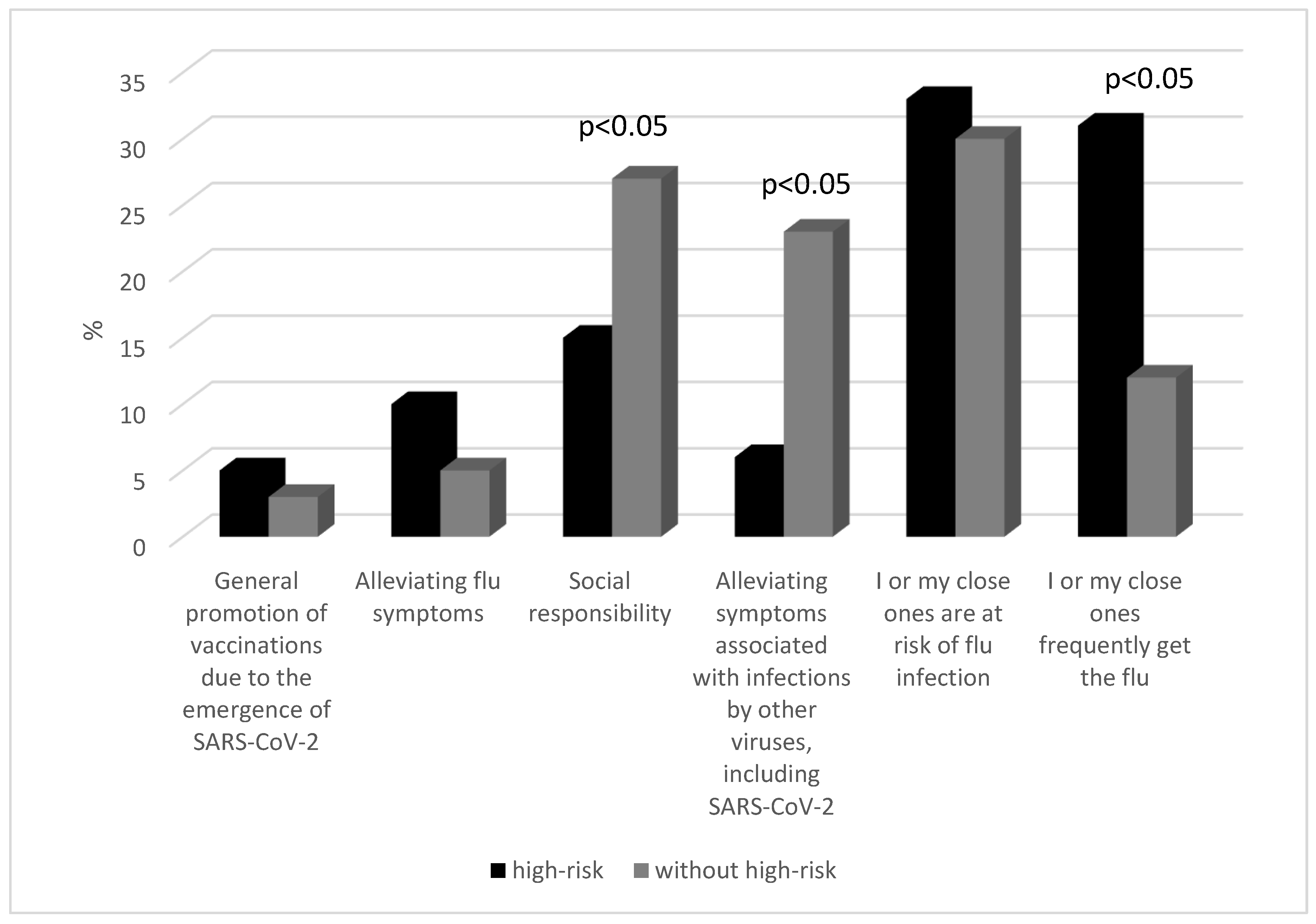

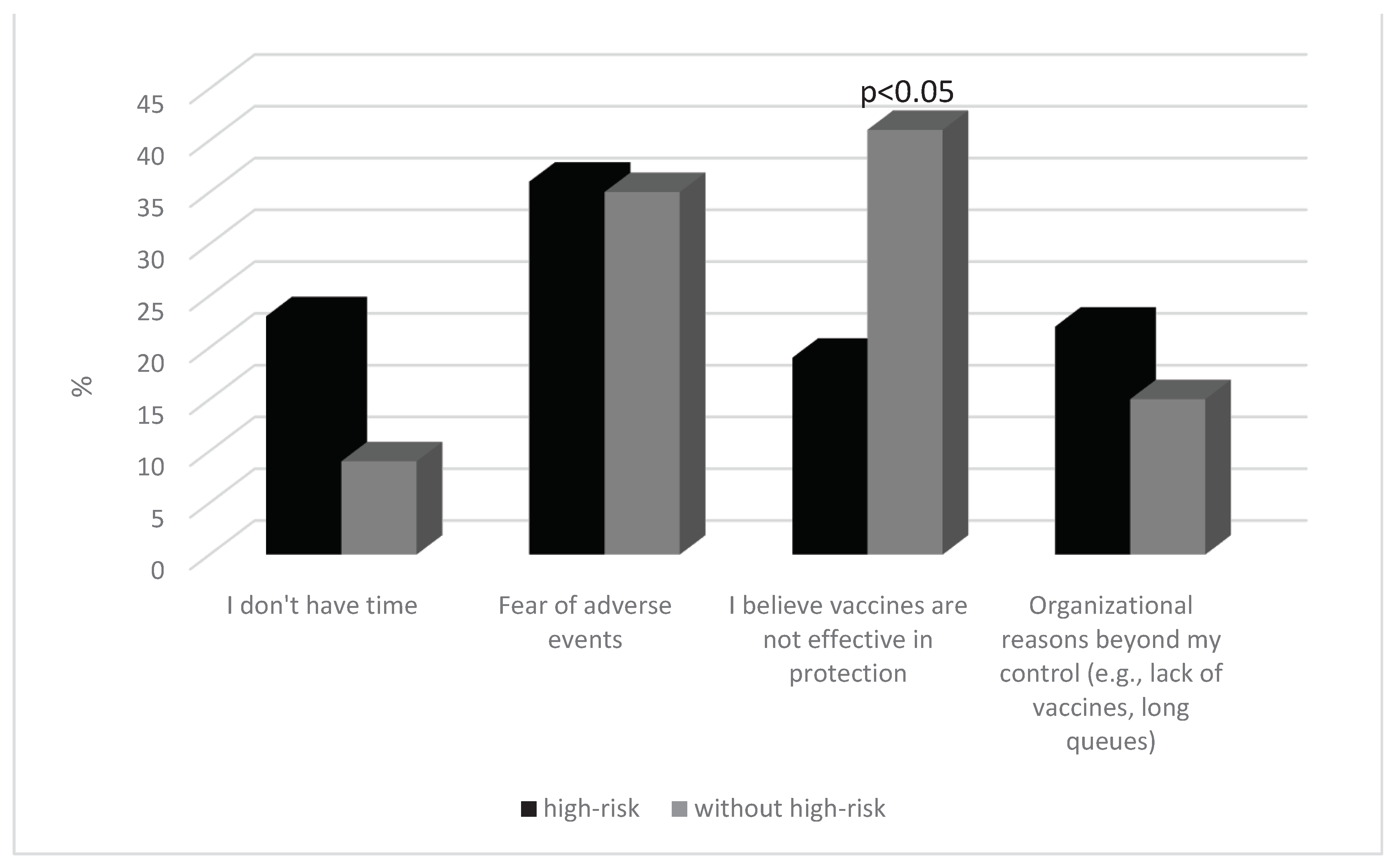

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaccines against Influenza WHO Position Paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012, 87, 461–476.

- Mortality, Morbidity, and Hospitalisations Due to Influenza Lower Respiratory Tract Infections, 2017: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 - The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(18)30496-X/fulltext (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Strategies. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/vaccines/vaccination-strategies (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Antiviral Use in EU/EEA Member States. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/seasonal-influenza-vaccination-antiviral-use-eu-eea-member-states (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Vandemaele, K.A.H.; Shinde, V.; Jaramillo-Gutierrez, G.; Koukounari, A.; Donnelly, C.A.; Carlino, L.O.; Owen, R.; Paterson, B.; Pelletier, L.; et al. Risk Factors for Severe Outcomes Following 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Infection: A Global Pooled Analysis. PLoS Med 2011, 8, e1001053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, D.; Kim, T.H.; Johnstone, J.; Lam, P.-P.; Science, M.; Kuster, S.P.; Fadel, S.A.; Tran, D.; Fernandez, E.; Bhatnagar, N.; et al. Populations at Risk for Severe or Complicated Influenza Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2013, 347, f5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC People at High Risk of Flu. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Seasonal Influenza 2022-2023 Annual Epidemiological Report 2023. 2023.

- Influenza Vaccination Coverage Rates in the EU/EEA. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/vaccines/vaccination-coverage (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Health Care Use - Influenza Vaccination Rates - OECD Data. Available online: http://data.oecd.org/healthcare/influenza-vaccination-rates.htm (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- State of Vaccine Confidence in the EU (2022) - European Commission. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/state-vaccine-confidence-eu-2022_en (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Vaccine Scheduler | ECDC. Available online: https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByCountry?SelectedCountryId=166&IncludeChildAgeGroup=true&IncludeChildAgeGroup=false&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=true&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=false/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Influenza Vaccination Coverage and Effectiveness. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/influenza-vaccination-coverage-and-effectiveness (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Announcement of the Minister of Health of 20 August 2021, on the List of Reimbursed Drugs, Foodstuffs for Particular Nutritional Uses and Medical Devices. J. Laws Minist. Health 2021, 65. Available online: http://Dziennikmz.Mz.Gov.Pl/Legalact/2021/65.

- The Polish National Program for Influenza Prevention. Expert Consensus on the Need for Influenza Vaccines in the 2021/202 Season. Available online: http://Opzg.Cn-Panel.Pl/Resources/Konsensus/2021_03_09_Konsensus_ekspert%C3%B3w_szacuknkowe_liczby_dawek.Dokument.Pdf.

- Canada, P.H.A. of Highlights from the 2021–2022 Seasonal Influenza (Flu) Vaccination Coverage Survey. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-vaccines/vaccination-coverage/seasonal-influenza-survey-results-2021-2022.html (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Roumeliotis, P.; Houle, S.K.D.; Johal, A.; Roy, B.; Boivin, W. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Self-Reported Rates of Influenza Immunization among Canadians at High Risk from Influenza: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, B.; Zou, X.; Liu, G.; Han, X. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice towards Influenza Vaccination among Older Adults in Southern China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Near, A.M.; Tse, J.; Young-Xu, Y.; Hong, D.K.; Reyes, C.M. Burden of Influenza Hospitalization among High-Risk Groups in the United States. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.-L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior – A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005 – 2016. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, G.; Basta, N.E.; Wolfson, C.; Kirkland, S.A.; McMillan, J.; Griffith, L.E.; Raina, P. Influenza Vaccination Uptake among Canadian Adults before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Vaccine 2022, 40, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Houle, S.K.D. ; Alsabbagh, Mhd. W. The Trends and Determinants of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination after Cardiovascular Events in Canada: A Repeated, Pan-Canadian, Cross-Sectional Study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2023, 43, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyles, T.J.; Stevens, H.P.; Obray, A.M.; Jensen, J.L.; Miner, D.S.; Bodily, R.J.; Nielson, B.U.; Poole, B.D. Changes in Attitudes and Barriers to Seasonal Influenza Vaccination from 2007 to 2023. J Community Health 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | General | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years; mean(±SD)] | 38.32 (3.86) | |||

| Sex [female; N (%)] | 467(57.67) | |||

| Place of residence | Village | 90(11.12) | ||

| A town with up to 50,000 residents | 97(12.01) | |||

| A town with up to 100,000 residents | 197(24.33) | |||

| A town with up to 250,000 residents | 206(25,42) | |||

| A city with over 250,000 residents | 220(27.12) | |||

| Education | Elementary | 140(17.39) | ||

| Vocational school | 211(26.06) | |||

| High school | 196(24.04) | |||

| College/University | 263(32.51) | |||

| High-risk group | Without; N(%) | 500(61.77) | ||

| With; N(%) | 310(38.23) | |||

| Anemia, thalassemia, hemoglobinopathy | 16(2.05) | |||

| Asthma | 60(7.50) | |||

| BMI > 40 kg/m | 28(3.47) | |||

| Cancer | 8(1.49) | |||

| Chronic CSF leak | 5(0.67) | |||

| Chronic lung disease1 | 82(10.12) | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 17(2.20) | |||

| Chronic liver disease | 10(1.30) | |||

| Hypertension | 285(35.21) | |||

| Heart disease2 | 100(12.33) | |||

| Respiratory secretion impairment3 | 10(1.21) | |||

| Immune disorder or immune suppression4 | 4(0.50) | |||

| Diabetes or other metabolic diseases | 122(15.10) | |||

| Spleen problems or removal | 9(1.09) | |||

| Other high-riskgroup | ≥65 years | 195(24.10) | ||

| Pregnant | 15(1.90) | |||

| Long-term care resident | 8(1.00) | |||

| Indigenous ancestry | 15(1.87) | |||

| Response[N(%)] | High-risk(%) | Age (%) | Education (%) | |||||||||

| with | without | ≤20 | 21- 40 | 41- 59 | ≥65 | Elementary | Vocational school | High school | College/University | |||

| How do you understand the phrase “40-70% vaccine effectiveness against the flu”?:(n=810) | Correct answer [421(52.00)] | 66.08 | 33.92 | 33.23 | 42.01 | 18.78 | 5.98 | 5.21 | 13.55 | 33.12 | 48.12 | |

| P-value | p < 0.0001 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.1116≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.0224≤20 vs 65: p = 0.005721-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.000321-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.018841-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0005 | Elementary vs vocational: p = 0.3022Elementary vs High school: p = 0.0089Elementary vs College :p = 0.0002Vocational vs High school: p = 0.0053Vocational vs College: p < 0.0001High school vs College: p = 0.0058 | |||||||||

| Do you know what the risk groups for influenza infection are? (n=810) | Yes [575(71.00)] | 77.83 | 22.17 | 15.16 | 33.76 | 34.44 | 16.64 | 2.28 | 9.98 | 25.15 | 62.77 | |

| P-value | p < 0.0001 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.0013≤20vs41-59 p = 0.0009≤20vs65 p = 0.785221-40vs41-59 p = 0.887121-40 vs ≥65 p = 0.002441-59 vs ≥65 p = 0.0016 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.3703Elementary vs High school: p = 0.0616Elementary vs College: p < 0.0001Vocational vs High school: p = 0.0170Vocational vs College: p < 0.0001High school vs College: p < 0.0001 | |||||||||

| Have you been confirmed to have a SARS-CoV-2 infection in the last season (2022-2023)?(n=810) | Yes[543(67.00)] | 67.09 | 32.91 | 2.69 | 25.12 | 28.10 | 44.09 | 26.49 | 23.98 | 24.03 | 25.50 | |

| P-value | p < 0.0001 | ≤20vs21-40 p = 0.0577≤20vs41-59 p = 0.0380≤20vs65 p = 0.002321-40vs41-59 p = 0.568221-40vs ≥65 p = 0.000341-59vs ≥65 p = 0.0015 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.6337Elementary vs High school: p = 0.6406Elementary vs College: p = 0.8500Vocational vs High school: p = 0.9925Vocational vs College: p = 0.7733High school vs College: p = 0.7806 | |||||||||

| Have you been confirmed to have a flu virus infection in the last season(2022-2023)? (n=810) | Yes [291(36.00)] | 68.77 | 31.23 | 7.62 | 17.85 | 35.43 | 39.10 | 7.00 | 21.77 | 23.80 | 47.43 | |

| P-value | p < 0.0001 | ≤20vs21-40 p = 0.2583≤20vs41-59 p = 0.0101≤20vs65 p = 0.004321-40vs41-59 p = 0.024521-40vs ≥65 p = 0.007241-59vs ≥65 p = 0.5776 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.1359Elementary vs High school: p = 0.0983Elementary vs College: p = 0.0006Vocational vs High school: p = 0.7814Vocational vs College: p = 0.0006High school vs College: p = 0.0010 | |||||||||

| Have you ever received the flu vaccine?(n=810) | Yes [421.2(52.01%)] | ever in the past [40(26.79)] | 70.01 | 29.99 | 6.75 | 5.07 | 18.87 | 69.31 | 24.12 | 51.23 | 13.09 | 11.56 |

| p = 0.0188 | ≤20vs21-40 p = 0.9386≤20vs41-59 p = 0.6250≤20vs65 p = 0.033221-40vs41-59 p = 0.637021-40vs ≥65 p = 0.066341-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0156 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.1723Elementary vs High scool: p = 0.6222Elementary vs College: p = 0.6030Vocational vs High school: p = 0.1240Vocational vs College: p = 0.1451High school vs College: p = 0.9448 | ||||||||||

| during the 2022-2023 flu season [48(32.12)] | 81.08 | 18.92 | 12.65 | 19.95 | 29.13 | 58.27 | 26.09 | 24.98 | 24.43 | 24.50 | ||

| p = 0.0003 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.7125≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.4338≤20 vs 65: p = 0.043221-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.626621-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.046441-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0842 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.9514Elementary vs High school: p = 0.9271Elementary vs College: p = 0.9302Vocational vs High school: p = 0.9761Vocational vs College: p = 0.9792High school vs College: p = 0.9970 | ||||||||||

| in the previous 2021-2022 flu season [61(41.09] | 68.22 | 31.78 | 4.86 | 16.07 | 23.09 | 55.98 | 20.08 | 26.12 | 27.12 | 26.68 | ||

| p = 0.0071 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.6197≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.4727≤20 vs 65: p = 0.089421-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.672621-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.026241-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0378 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.7093Elementary vs High school: p = 0.6665Elementary vs College: p = 0.6851Vocational vs High school: p = 0.9490Vocational vs College: p = 0.9713High school vs College: p = 0.9776 | ||||||||||

| Did you experience any adverse effects from receiving the flu vaccine? (n=149) | Yes [42 (28.08)] | 43.44 | 55.56 | 7.62 | 28.98 | 19.10 | 43.30 | 19.95 | 21.30 | 27.32 | 31.43 | |

| P-value | p =0.4343 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.4430≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.6434≤20 vs 65: p = 0.239021-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.617321-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.427541-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.2350 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.9372Elementary vs Hihg school: p = 0.7112Elementary vs College: p = 0.5652Vocational vs High school: p = 0.7558Vocational vs College: p = 0.6000High school vs College: p = 0.8260 | |||||||||

| How severe were the adverse effects you experienced after receiving the flu vaccine?(n=42) | Mild [27(65.28)] | 63.89 | 36.11 | 26.12 | 1.77 | 33.65 | 38.46 | 30.72 | 29.36 | 18.74 | 21.18 | |

| P-value | p = 0.1622 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = N.D.≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.7512≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.595421-40 vs 41-59: p = N.D.21-40 vs ≥65: p = N.D.41-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.8275 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.9527Elementary vs High school: p = 0.6324Elementary vs College: p = 0.4113Vocational vs High school: p = 0.6682Vocational vs College: p = 0.7294High school vs College: p = 0.9199 | |||||||||

| Moderate [13(31.22)] | 62.10 | 37.90 | 20.62 | 21.10 | 28.17 | 30.11 | 17.20 | 25.99 | 29.81 | 27.00 | ||

| P-value | p = 0.3549 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.9906≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.8488≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.804921-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.858721-40 vs ≥ 65: p = 0.814941-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.9555 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.8176Elementary vs High school: p = 0.7387Elementary vs College: p = 0.7989Vocational vs High school: p = 0.9115Vocational vs College: p = 0.9776High school vs College: p = 0.9351 | |||||||||

| Severe [1(3.50)] | 100 | 0 | 12.66 | 12.32 | 34.12 | 40.09 | 28.17 | 33.10 | 24.88 | 13.85 | ||

| - | p = N.D. | p = N.D. | ||||||||||

| Did you receive both: the flu and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines during the 2022-2023 season?(n=810) | Yes [140(17.28)] | 81.08 | 18.92 | 16.51 | 16.69 | 29.10 | 37.70 | 24.10 | 17.99 | 26.48 | 31.43 | |

| P-value | p < 0.0001 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.9869≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.2633≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.067821-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.268221-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.069541-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.3879 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.5746Elementary vs High school: p = 0.8193Elementary vs College: p = 0.4797Vocational vs High school: p = 0.4362Vocational vs College: p = 0.2244High school vs College: p = 0.6254 | |||||||||

| How many doses of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccinehave you received during the season 2022-2023? ( n=140) | 1 [12(8.53)] | 41.01 | 58.99 | 26.12 | 1.77 | 33.65 | 38.46 | 24.12 | 51.23 | 13.09 | 11.56 | |

| 2 [13(9.12)] | 33.87 | 66.13 | 41.23 | 12.38 | 27.15 | 19.24 | 29.09 | 31.65 | 39.26 | 36.47 | ||

| 3 [80(57.02)] | 91.10 | 8.90 | 3.69 | 29.12 | 33.43 | 33.76 | 44.10 | 38.12 | 17.78 | 28.98 | ||

| 4 [35(25.33)] | 87.28 | 12.72 | 12.65 | 19.95 | 29.13 | 58.27 | 26.49 | 23.98 | 24.03 | 25.50 | ||

| In your opinion, does the flu vaccine you’ve received alleviate the symptoms of a SARS-CoV-2 infection? (n=140) | Yes [94(67.09)] | 71.99 | 28.01 | 4.86 | 16.07 | 23.09 | 55.98 | 20.08 | 26.12 | 27.12 | 26.68 | |

| P-value | p = 0.0001 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.5625≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.4050≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.048521-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.604821-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.006441-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0108 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.6433Elementary vs High school: p = 0.5948Elementary vs College: p = 0.6167Vocational vs High school: p = 0.9369Vocational vs College: p = 0.9645High school vs College: p = 0.9720 | |||||||||

| Do you plan to get regular flu vaccinations in the future seasons?(n=810) | Yes [211 (26.12)] | 46.79 | 24.81 | 12.66 | 12.32 | 34.12 | 40.09 | 31.76 | 38.44 | 29.80 | 0 | |

| P-value | p = 0.0087 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.9704≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.0376≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.009721-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.034521-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.008841-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.4422 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.3977Elementary vs High school: p = 0.8097Elementary vs College: p = N.D.Vocational vs High school: p = 0.2821Vocational vs College: p = N.D.High school vs College: p = N.D. | |||||||||

| No [373(46.00)] | 22.12 | 40.09 | 19.16 | 33.76 | 30.44 | 16.64 | 33.10 | 37.32 | 20.58 | 9.58 | ||

| P-value | p = 0.0057 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.0293≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.0898≤20 vs 65: p = 0.705821-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.583421-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.014141-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.0453 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.4758Elementary vs High school: p = 0.0568Vocational vs College: p = 0.0062Vocational vs High school: p = 0.0115High school vs College: p = 0.0016Vocational vs Hihg school: p = 0.1528 | |||||||||

| Not sure [226(27.88)] | 31.09 | 35.10 | 26.12 | 1.77 | 33.65 | 38.46 | 40.10 | 36.12 | 17.78 | 6.00 | ||

| P-value | p = 0.6040 | ≤20 vs 21-40: p = 0.3244≤20 vs 41-59: p = 0.1602≤20 vs ≥65: p = 0.044121-40 vs 41-59: p = 0.183021-40 vs ≥65: p = 0.136941-59 vs ≥65: p = 0.5239 | Elementary vs Vocational: p = 0.5928Elementary vs High school: p = 0.0126Elementary vs College: p = 0.0165Vocational vs Hihg school: p = 0.0385Vocational vs College: p = 0.0306High school vs College: p = 0.3000 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).