Submitted:

22 February 2024

Posted:

24 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

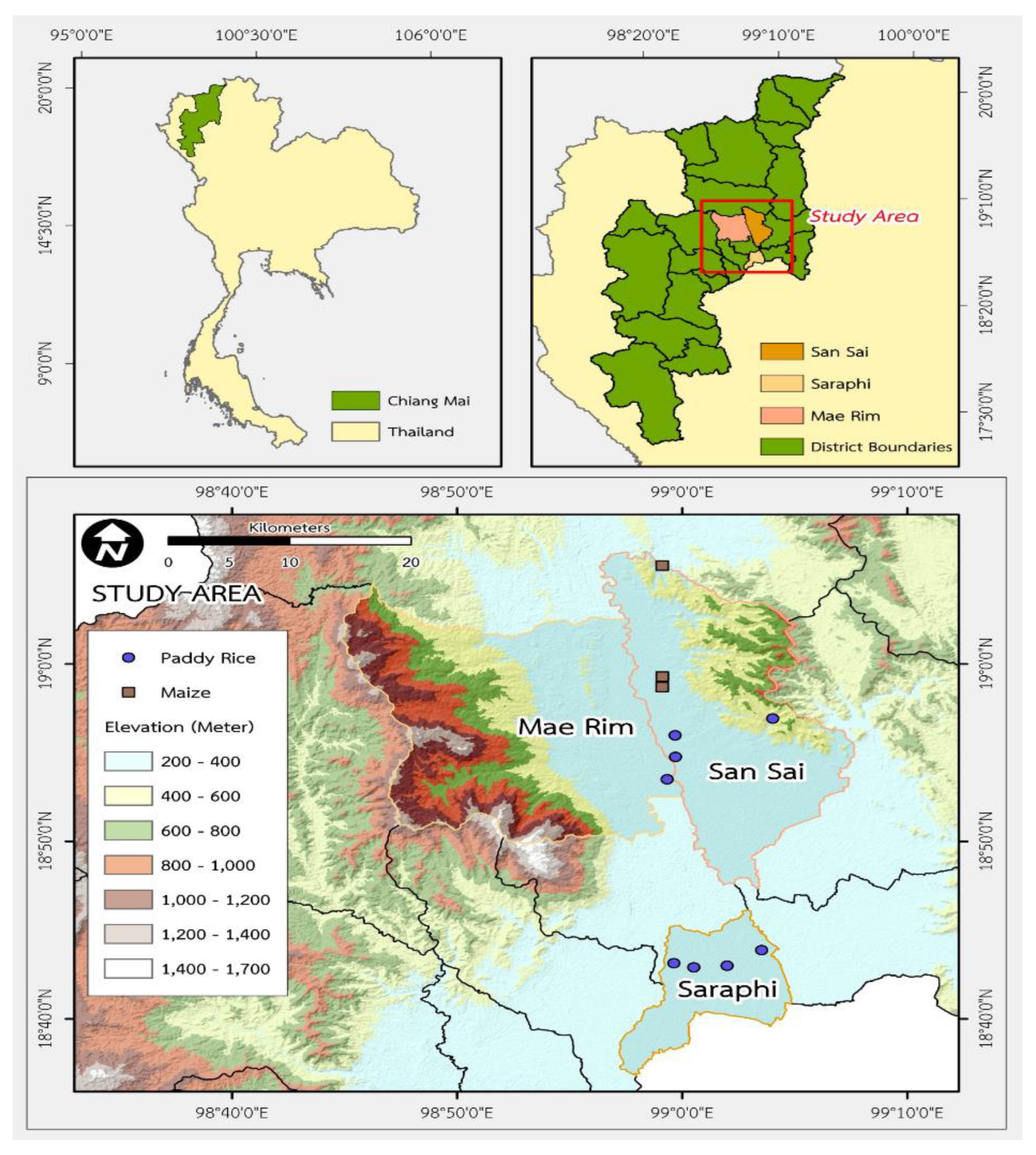

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

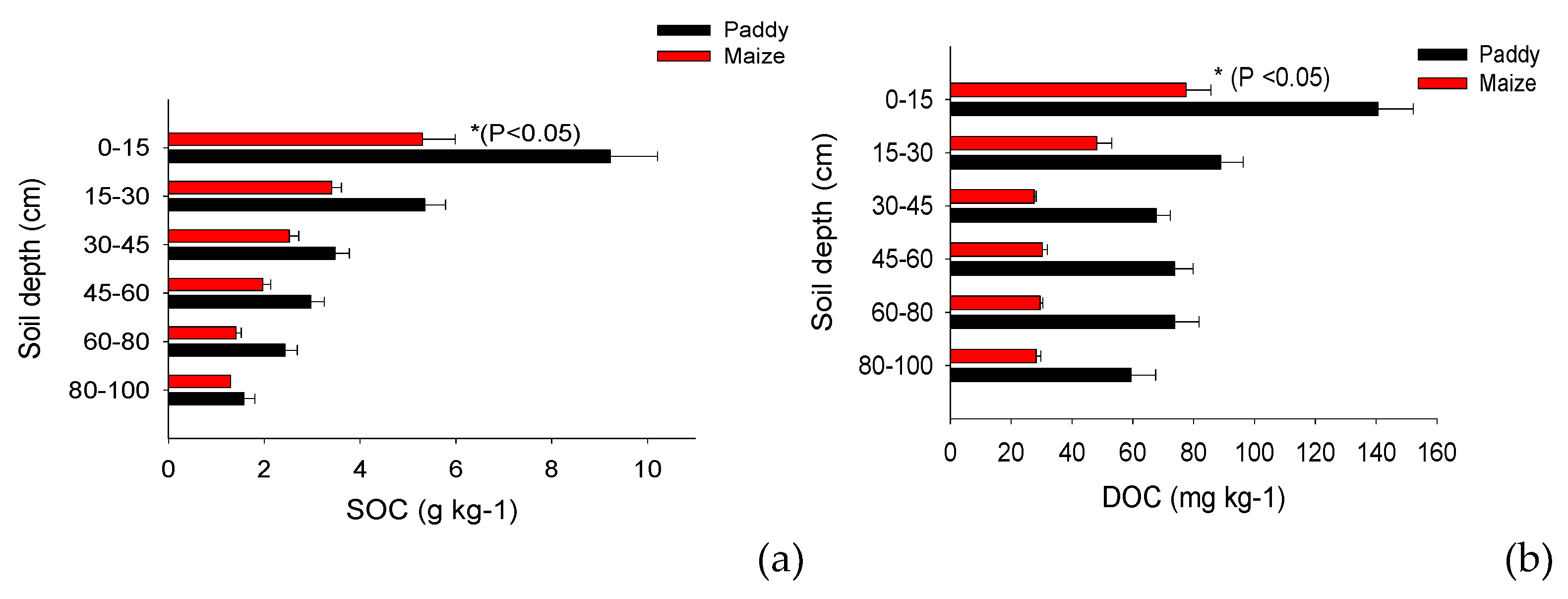

Comparison of SOC and DOC between maize and paddy soil

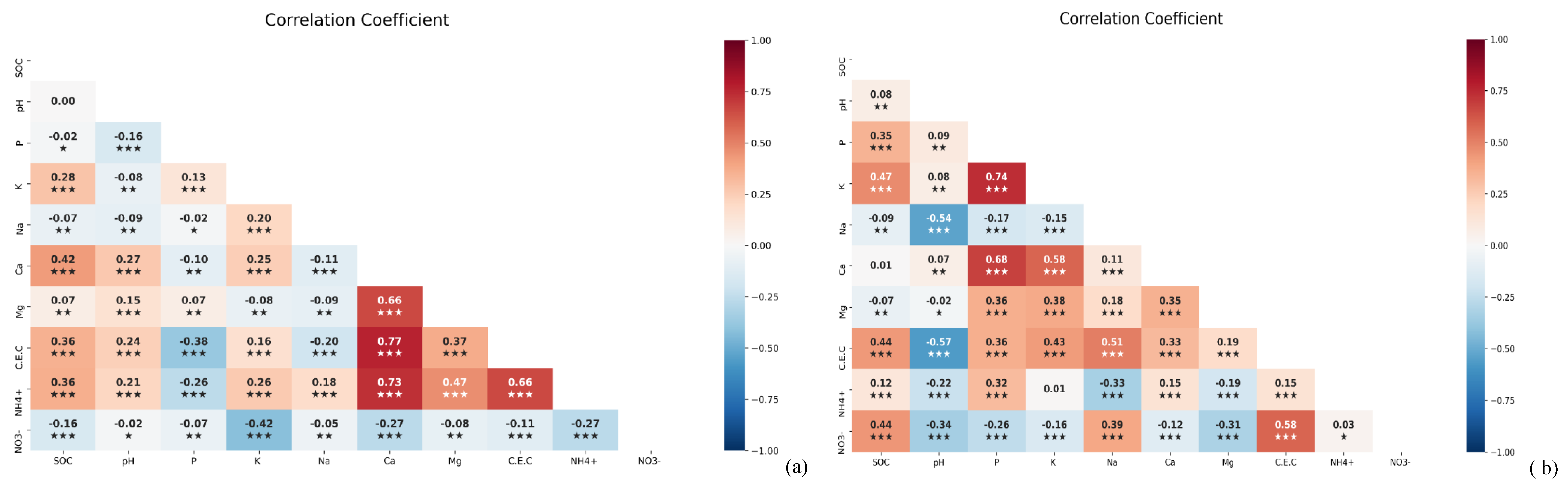

The chemical properties of maize and paddy soils

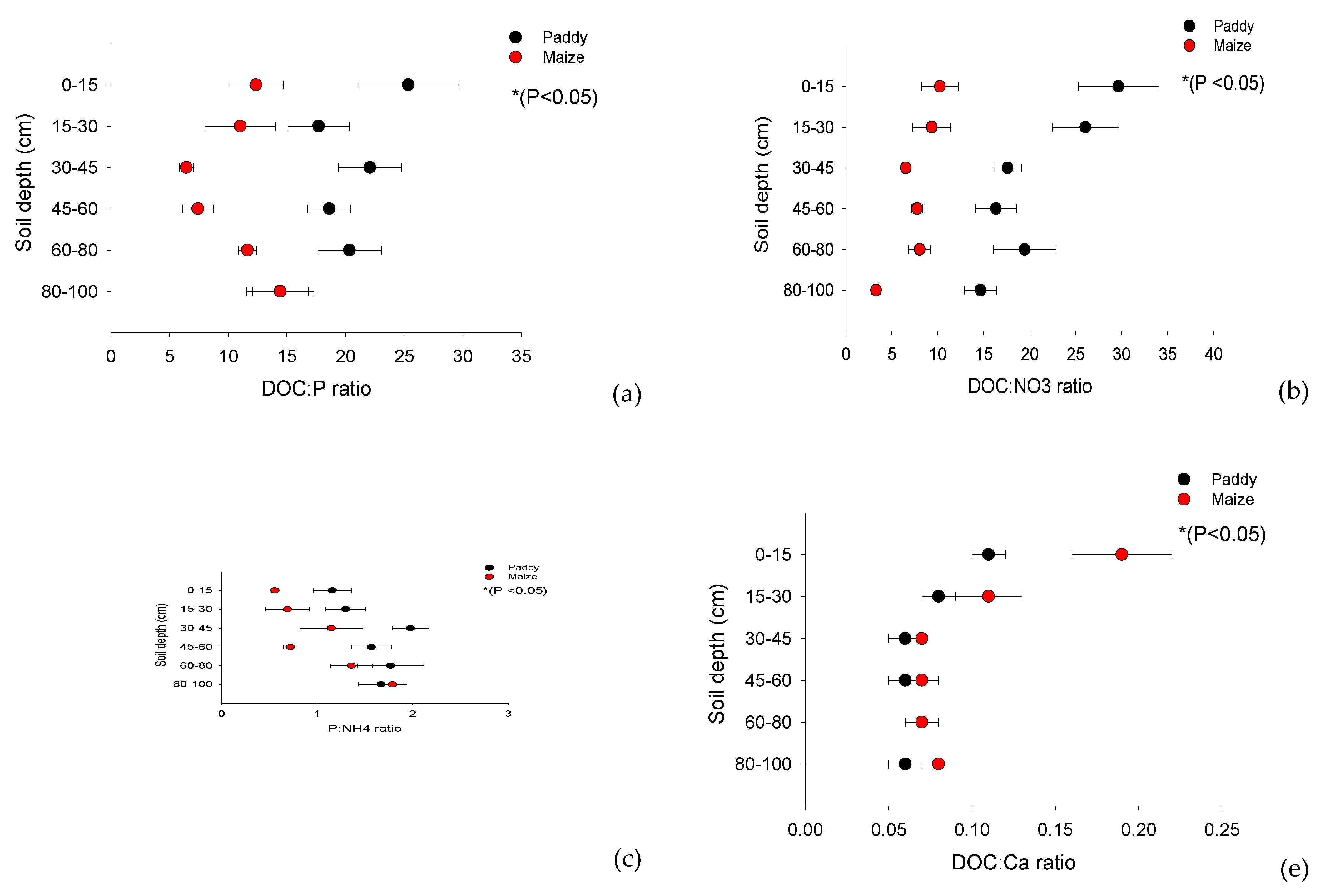

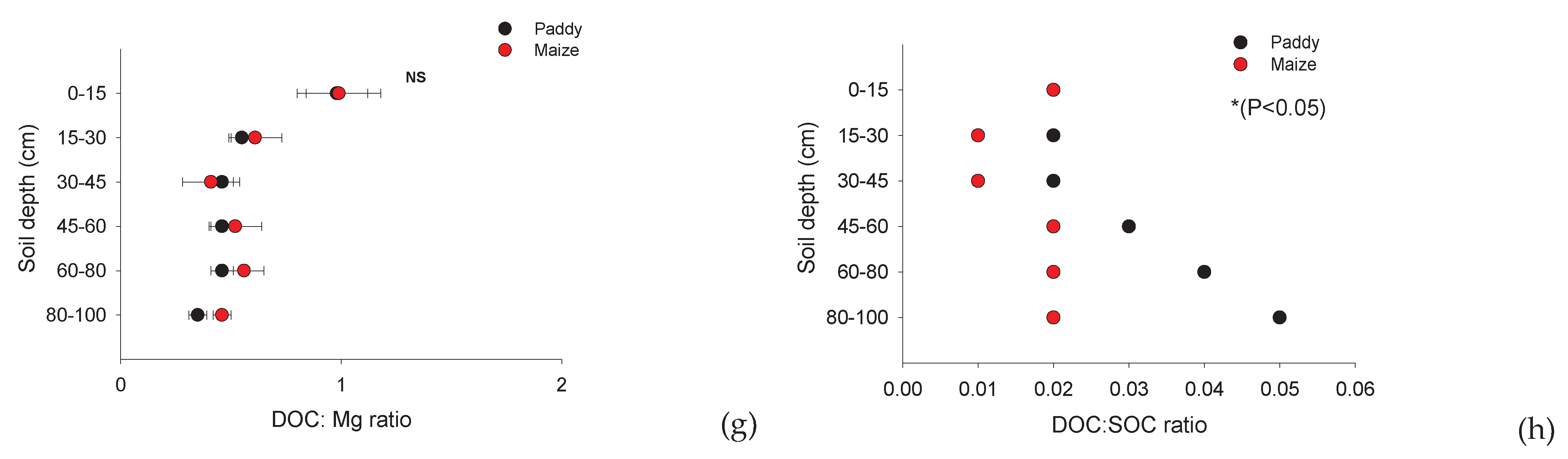

DOC and availability of nutrients

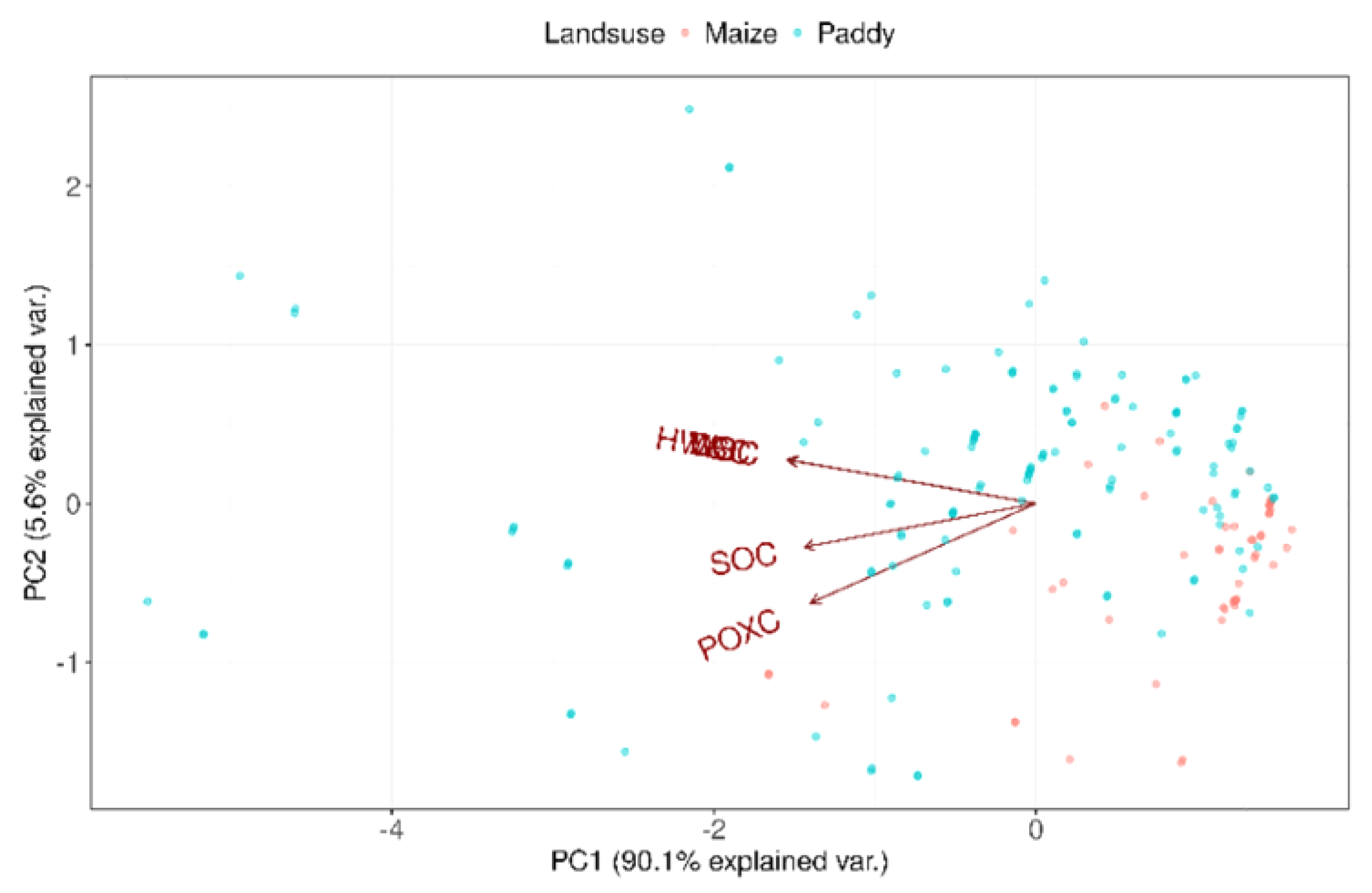

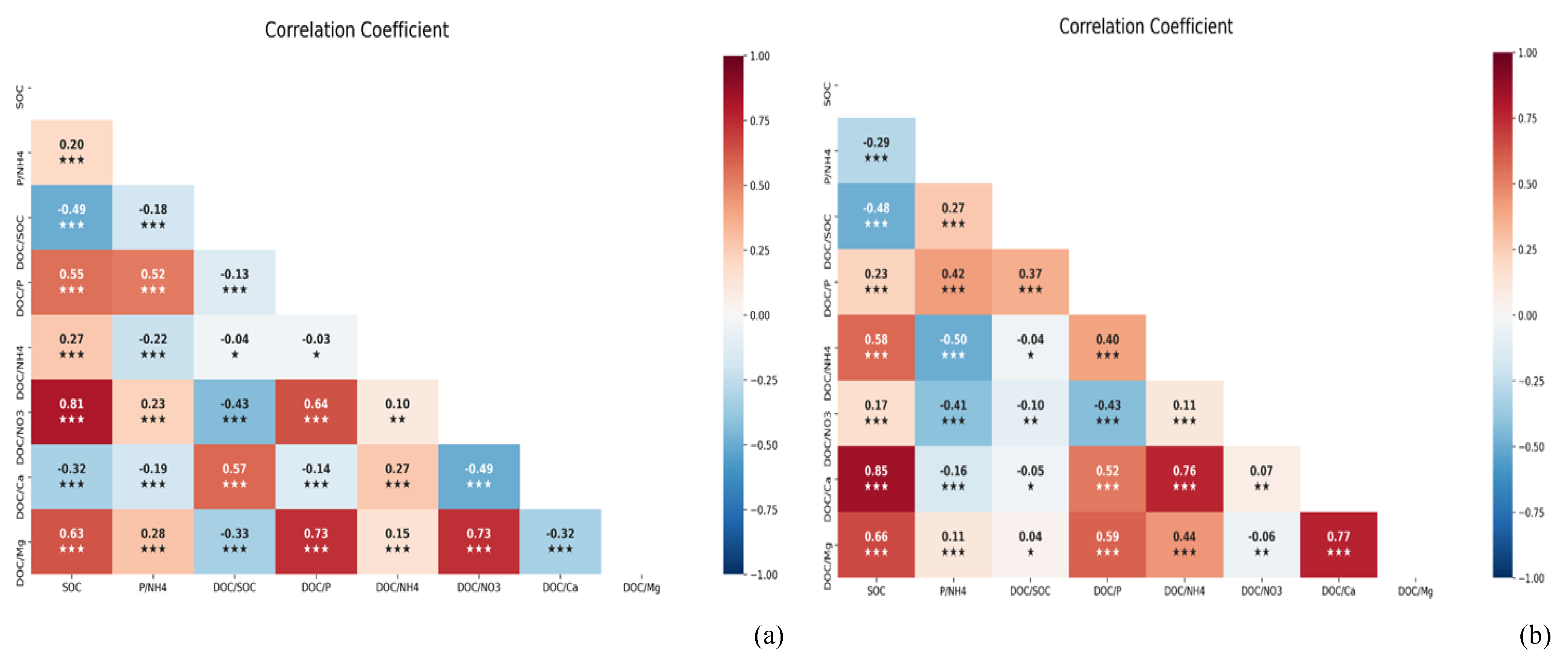

The effect of DOC and nutrients on SOC

4. Discussion

The size of mineral fertiliser on SOC

Effect of DOC on the changed availability of C in maize and paddy soils

Effects of chemical properties of the soil and availability of basic cation on SOC retention

Effect of availability of Ca on DOC and SOC retention

Effect of availability of nutrients and DOC on SOC retention

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lal, R. Forest Soils and Carbon Sequestration. Forest Ecology and Management 2005, 220, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Carbon Sequestration in Dryland Ecosystems. Environmental Management 2004, 33, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil degradation as a reason for inadequate human nutrition. Food Security 2009, 1, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, T.B.; de Neergaard, A.; Burup, M.L.; Hepp, C.M.; Larsen, M.N.; Abel, C.; Aumtong, S.; Magid, J.; Mertz, O. Intensification of Upland Agriculture in Thailand: Development or Degradation? Land Degradation & Development 2017, 28, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnuaylojaroen, T.; Chanvichit, P.; Janta, R.; Surapipith, V. Projection of Rice and Maize Productions in Northern Thailand under Climate Change Scenario RCP8.5. Agriculture 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Taba, S.; Tovar, V.H.C.; Mezzalama, M.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Crouch, J.H. Conserving and Enhancing Maize Genetic Resources as Global Public Goods–A Perspective from CIMMYT. Crop Science 2010, 50, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisurat, Y.; Shirakawa, H.; Johnston, J.M. Land-Use/Land-Cover Change from Socio-Economic Drivers and Their Impact on Biodiversity in Nan Province, Thailand. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechert, G.; Veldkamp, E.; Anas, I. Is soil degradation unrelated to deforestation? Examining soil parameters of land use systems in upland Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Plant and Soil 2004, 265, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippe, M.; Hilger, T.; Sudchalee, S.; Wechpibal, N.; Jintrawet, A.; Cadisch, G. Simulating Stakeholder-Based Land-Use Change Scenarios and Their Implication on Above-Ground Carbon and Environmental Management in Northern Thailand. Land 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Mitani, R.; Inagaki, Y.; Hayakawa, C.; Shibata, M.; Kosaki, T.; Ueda, M.U. Continuous maize cropping accelerates loss of soil organic matter in northern Thailand as revealed by natural 13C abundance. Plant and Soil 2022, 474, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, L.; Su, Y.; Yuan, H.; Syers, J.K. Restricted mineralization of fresh organic materials incorporated into a subtropical paddy soil. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2012, 92, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumtong, S.; Chotamonsak, C.; Glomchinda, T. Study of the Interaction of Dissolved Organic Carbon, Available Nutrients, and Clay Content Driving Soil Carbon Storage in the Rice Rotation Cropping System in Northern Thailand. Agronomy 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumtong, S.; Chotamonsak, C.; Somchit, B. The increased carbon storage changes with a decrease in phosphorus availability in the organic paddy soil. Ilmu Pertanian (Agricultural Science) 2022, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Bradford, M.A.; Wood, S.A. Global meta-analysis of the relationship between soil organic matter and crop yields. SOIL 2019, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, R.J.; Bossio, D.A.; Sommer, R.; Verchot, L.V. Global Sequestration Potential of Increased Organic Carbon in Cropland Soils. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 15554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, T.; Bolan, N.S.; Kirkham, M.B.; Wijesekara, H.; Kanchikerimath, M.; Srinivasa Rao, C.; Sandeep, S.; Rinklebe, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Choudhury, B.U.; et al. Chapter One - Soil organic carbon dynamics: Impact of land use changes and management practices: A review. In Advances in Agronomy, Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: 2019; Volume 156, pp. 1-107.

- Paterson, E.; Sim, A. Soil-specific response functions of organic matter mineralization to the availability of labile carbon. Global Change Biology 2013, 19, 1562–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jílková, V.; Jandová, K.; Kukla, J. Responses of microbial activity to carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus additions in forest mineral soils differing in organic carbon content. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2021, 57, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Troyer, I.; Amery, F.; Van Moorleghem, C.; Smolders, E.; Merckx, R. Tracing the source and fate of dissolved organic matter in soil after incorporation of a 13C labelled residue: A batch incubation study. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2011, 43, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Wu, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Gregorich, E.G. Priming effect of maize residue and urea N on soil organic matter changes with time. Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 100, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottingham, A.T.; Griffiths, H.; Chamberlain, P.M.; Stott, A.W.; Tanner, E.V.J. Soil priming by sugar and leaf-litter substrates: A link to microbial groups. Applied Soil Ecology 2009, 42, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Cai, G.; Sauheitl, L.; Xiao, M.; Shibistova, O.; Ge, T.; Guggenberger, G. Meta-analysis on the effects of types and levels of N, P, and K fertilization on organic carbon in cropland soils. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms – A review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Nobuntou, W.; Punlai, N.; Sugino, T.; Rujikun, P.; Luanmanee, S.; Kawamura, K. Soil carbon sequestration on a maize-mung bean field with rice straw mulch, no-tillage, and chemical fertilizer application in Thailand from 2011 to 2015. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2021, 67, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M. Dissolved organic carbon and bioavailability of N and P as indicators of soil quality. Scientia Agricola 2005, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laik, R.; Kumara, B.H.; Pramanick, B.; Singh, S.K.; Nidhi; Alhomrani, M.; Gaber, A.; Hossain, A. Labile Soil Organic Matter Pools Are Influenced by 45 Years of Applied Farmyard Manure and Mineral Nitrogen in the Wheat—Pearl Millet Cropping System in the Sub-Tropical Condition. Agronomy 2021, 11. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.G.; Wright, A.; Hons, F.M. Dissolved and Soil Organic Carbon after Long-Term Conventional and No-Tillage Sorghum Cropping. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2008, 39, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Castellano, M.J.; Ye, C.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, J.; Ding, W. Oxygen availability regulates the quality of soil dissolved organic matter by mediating microbial metabolism and iron oxidation. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 7410–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, K.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. Different responses of soil carbon chemistry to fertilization regimes in the paddy soil and upland soil were mainly reflected by the opposite shifts of OCH and alkyl C. Geoderma 2021, 385, 114876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H. Evaluation of Holistic Approaches to Predicting the Concentrations of Metals in Field-Cultivated Rice. Environmental Science & Technology 2008, 42, 7649–7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.R.; Harir, M.; Shukle, J.T.; Schroth, A.W.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Druschel, G.K. Seasonal transformations of dissolved organic matter and organic phosphorus in a polymictic basin: Implications for redox-driven eutrophication. Chemical Geology 2021, 573, 120212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, C.; Spencer, R.G.M.; Maie, N.; Hur, J.; McKenna, A.M.; Yan, F. Climatic, land cover, and anthropogenic controls on dissolved organic matter quantity and quality from major alpine rivers across the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau. Sci Total Environ 2021, 754, 142411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, T.; Rékási, M. Factors controlling dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and DOC/DON ratio in arable soils based on a dataset from Hungary. Geoderma 2011, 162, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Wang, A.H.; Hu, L.N.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; He, X.Y.; Su, Y.R. [Response of mineralization of dissolved organic carbon to soil moisture in paddy and upland soils in hilly red soil region]. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2014, 25, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Wu, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Gregorich, E.G. Effects of plant-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) on soil CO2 and N2O emissions and soil carbon and nitrogen sequestrations. Applied Soil Ecology 2015, 96, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ge, T.; Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Tong, C.; Shibistova, O.; Guggenberger, G.; Wu, J. Microbial stoichiometric flexibility regulates rice straw mineralization and its priming effect in paddy soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 121, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.; Long, X.-E. Microbes in a neutral-alkaline paddy soil react differentially to intact and acid washed biochar. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2022, 22, 3137–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, S.; Richter, A.; Shibistova, O.; Guggenberger, G.; et al. C:N:P stoichiometry regulates soil organic carbon mineralization and concomitant shifts in microbial community composition in paddy soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2020, 56, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Singh, R.; Bhadouria, R.; Singh, P.; Tripathi, S.; Singh, H.; Raghubanshi, A.S.; Mishra, P.K. Physical and Biological Processes Controlling Soil C Dynamics. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 33: Climate Impact on Agriculture, Lichtfouse; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 171–202. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Guo, S.; Wan, Z.; Huang, G.; Xu, H. Impacts of Rotation-Fallow Practices on Bacterial Community Structure in Paddy Fields. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e00227–00222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Meng, T.; Qian, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z. Evidence for nitrification ability controlling nitrogen use efficiency and N losses via denitrification in paddy soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2017, 53, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabtai, I.A.; Wilhelm, R.C.; Schweizer, S.A.; Höschen, C.; Buckley, D.H.; Lehmann, J. Calcium promotes persistent soil organic matter by altering microbial transformation of plant litter. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittinghill, K.A.; Hobbie, S.E. Effects of pH and calcium on soil organic matter dynamics in Alaskan tundra. Biogeochemistry 2012, 111, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oste, L.A.; Temminghoff, E.J.M.; Riemsdijk, W.H.V. Solid-solution Partitioning of Organic Matter in Soils as Influenced by an Increase in pH or Ca Concentration. Environmental Science & Technology 2002, 36, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.R.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Contribution of Soil Organic Carbon to the Ion Exchange Capacity of Tropical Soils. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2008, 32, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Dexter, M.; Carran, R.A.; Theobald, P.W. Dissolved organic nitrogen and carbon in pastoral soils: the New Zealand experience. European Journal of Soil Science 2007, 58, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Müller, K.; Dodd, M.; Mackay, A. Dissolved organic matter leaching in some contrasting New Zealand pasture soils. European Journal of Soil Science 2010, 61, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis; SSSA Book Series; 1996; pp. 961-1010.

- Wade, J.; Maltais-Landry, G.; Lucas, D.E.; Bongiorno, G.; Bowles, T.M.; Calderón, F.J.; Culman, S.W.; Daughtridge, R.; Ernakovich, J.G.; Fonte, S.J.; et al. Assessing the sensitivity and repeatability of permanganate oxidizable carbon as a soil health metric: An interlab comparison across soils. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.; Stine, M.; Gruver, J.; Samson-Liebig, S. Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for laboratory and field use. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 2003, 18, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, E.O. Soil pH and Lime Requirement. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; 1983; pp. 199-224.

- Keeney, D.R.; Nelson, D.W. Nitrogen—Inorganic Forms. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; 1983; pp. 643-698.

- Chapman, H.D. Cation-Exchange Capacity. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; 1965; pp. 891-901.

- Ge, T.; Luo, Y.; Singh, B.P. Resource stoichiometric and fertility in soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2020, 56, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.; Franklin, O.; Dieckmann, U.; Richter, A. Microbial community dynamics alleviate stoichiometric constraints during litter decay. Ecology Letters 2014, 17, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Huan, W.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Effects of straw incorporation and potassium fertilizer on crop yields, soil organic carbon, and active carbon in the rice–wheat system. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 209, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.W.; Jeong, S.T.; Kim, P.J.; Gwon, H.S. Influence of nitrogen fertilization on the net ecosystem carbon budget in a temperate mono-rice paddy. Geoderma 2017, 306, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Ge, T.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Kuzyakov, Y. Comparing carbon and nitrogen stocks in paddy and upland soils: Accumulation, stabilization mechanisms, and environmental drivers. Geoderma 2021, 398, 115121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tian, J.; Meersmans, J.; Fang, H.; Yang, H.; Lou, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E.; et al. Functional soil organic matter fractions in response to long-term fertilization in upland and paddy systems in South China. CATENA 2018, 162, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gou, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Yin, D. Stocks of soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in coniferous forests on the Qilian Mountains: spatial trends and drivers. European Journal of Forest Research 2023, 142, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Yin, X.; Savoy, H.J.; Jagadamma, S.; Lee, J.; Sykes, V. Long-term influence of phosphorus fertilization on organic carbon and nitrogen in soil aggregates under no-till corn–wheat–soybean rotations. Agronomy Journal 2020, 112, 2519–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, C.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, D. Effects of soil acidification and liming on the phytoavailability of cadmium in paddy soils of central subtropical China. Environmental Pollution 2016, 219, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmann, V.; Sousa, R.; Weinert, C.; Jordão, H.; Carlos, F. Soil solution and rice nutrition under liming and water management in a soil from Amazonian natural fields. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröberg, M.; Jardine, P.M.; Hanson, P.J.; Swanston, C.W.; Todd, D.E.; Tarver, J.R.; Garten, C.T. Low Dissolved Organic Carbon Input from Fresh Litter to Deep Mineral Soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2007, 71, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel-Knabner, I.; Amelung, W.; Cao, Z.; Fiedler, S.; Frenzel, P.; Jahn, R.; Kalbitz, K.; Kölbl, A.; Schloter, M. Biogeochemistry of paddy soils. Geoderma 2010, 157, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zheng, X.; Ge, T.; Dorodnikov, M.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z. Weaker priming and mineralisation of low molecular weight organic substances in paddy than in upland soil. European Journal of Soil Biology 2017, 83, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delprat, L.; Chassin, P.; Linères, M.; Jambert, C. Characterization of dissolved organic carbon in cleared forest soils converted to maize cultivation. European Journal of Agronomy 1997, 7, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbitz, K.; Schmerwitz, J.; Schwesig, D.; Matzner, E. Biodegradation of soil-derived dissolved organic matter as related to its properties. Geoderma 2003, 113, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.P.; Han, C.W.; Han, F.X. Organic C and N mineralization as affected by dissolved organic matter in paddy soils of subtropical China. Geoderma 2010, 157, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellman, J.B.; Hood, E.; D’Amore, D.V.; Edwards, R.T.; White, D. Seasonal changes in the chemical quality and biodegradability of dissolved organic matter exported from soils to streams in coastal temperate rainforest watersheds. Biogeochemistry 2009, 95, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, J.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic carbon decomposition from recently added and older sources estimated by δ13C values of CO2 and organic matter. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2012, 55, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, R.; Yu, Y.; Ge, C.; Yao, H. Soil Texture Alters the Impact of Salinity on Carbon Mineralization. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sarkar, B.; Hussain, S.; Ok, Y.S.; Bolan, N.S.; Churchman, G.J. Influence of physico-chemical properties of soil clay fractions on the retention of dissolved organic carbon. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2017, 39, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Y.; Xiong, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xie, J.; Gao, R.; Yang, Y. Contribution of the vertical movement of dissolved organic carbon to carbon allocation in two distinct soil types under Castanopsis fargesii Franch. and C. carlesii (Hemsl.) Hayata forests. Annals of Forest Science 2018, 75, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Tian, C. Soil organic carbon changes following wetland cultivation: A global meta-analysis. Geoderma 2019, 347, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.J.; Zheng, L.B.; Mei, X.Y.; Yu, L.Z.; Jia, Z.C. [Characteristics of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen under different land use types in Shanghai]. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2010, 21, 2279–2287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. Temperature effects on soil organic carbon, soil labile organic carbon fractions, and soil enzyme activities under long-term fertilization regimes. Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 102, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.D.; Monteith, D.T.; Cooper, D.M. Long-term increases in surface water dissolved organic carbon: Observations, possible causes and environmental impacts. Environmental Pollution 2005, 137, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solinger, S.; Kalbitz, K.; Matzner, E. Controls on the dynamics of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in a Central European deciduous forest. Biogeochemistry 2001, 55, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Song, C.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Gao, J.; Gao, S.; Wang, L. Linking soil organic carbon mineralization with soil microbial and substrate properties under warming in permafrost peatlands of Northeastern China. CATENA 2021, 203, 105348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ma, C.; Rui, Y.; He, H.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, T.; et al. Contrasting pathways of carbon sequestration in paddy and upland soils. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 2478–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-l.; Huang, J.; Li, D.-m.; Yu, X.-c.; Ye, H.-c.; Hu, H.-w.; Hu, Z.-h.; Huang, Q.-h.; Zhang, H.-m. Comparison of carbon sequestration efficiency in soil aggregates between upland and paddy soils in a red soil region of China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2019, 18, 1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, A.; Cerli, C.; Muhr, J.; Borken, W.; Kalbitz, K. Redox control on carbon mineralization and dissolved organic matter along a chronosequence of paddy soils. European Journal of Soil Science 2013, 64, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Ge, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of biotic and abiotic factors on soil organic matter mineralization: Experiments and structural modeling analysis. European Journal of Soil Biology 2018, 84, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Xu, N.; Sun, G.; Zhao, M. Land use change from upland to paddy field in Mollisols drives soil aggregation and associated microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology 2020, 146, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grybos, M.; Davranche, M.; Gruau, G.; Petitjean, P.; Pédrot, M. Increasing pH drives organic matter solubilization from wetland soils under reducing conditions. Geoderma 2009, 154, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, E.F.; Weber, V.; Zimmermann, S.; Walthert, L.; Hagedorn, F.; Schmidt, M.W.I. Is the content and potential preservation of soil organic carbon reflected by cation exchange capacity? A case study in Swiss forest soils. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2019, 2019, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, Z. Long-term changes in organic carbon and nutrients of an Ultisol under rice cropping in southeast China. Geoderma 2004, 118, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Maiti, S.K. Evaluation of ecological restoration success in mining-degraded lands. Environmental Quality Management 2019, 29, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, C.A. Clay Dispersion of Selected Aeolian Soils of Northern Nigeria in Relation to Sodicity and Organic Carbon Content. Arid Land Research and Management 2001, 15, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.N.L.; Greene, R.S.B.; Dalal, R.C.; Murphy, B.W. Soil carbon dynamics in saline and sodic soils: a review. Soil Use and Management 2010, 26, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Qu, Y.; Dai, Z. Carbon Mineralization under Different Saline—Alkali Stress Conditions in Paddy Fields of Northeast China. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Jiang, J.; Lin, L.; Wang, Y. Soil calcium prompts organic carbon accumulation after decadal saline-water irrigation in the Taklamakan desert. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 344, 118421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, M.C.; Grand, S.; Verrecchia, É.P. Calcium-mediated stabilisation of soil organic carbon. Biogeochemistry 2018, 137, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlap, E.; Steffens, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Initial soil aggregate formation and stabilisation in soils developed from calcareous loess. Geoderma 2021, 385, 114854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Wu, S.; Zhu, Q. Can Soil pH Be Used to Help Explain Soil Organic Carbon Stocks? CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water 2016, 44, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, P.; van der Gast, C.; Bending, G.D. Converting highly productive arable cropland in Europe to grassland: –a poor candidate for carbon sequestration. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 10493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z. Ammonium transformation in paddy soils affected by the presence of nitrate. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2002, 63, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Cai, Z.; Müller, C. Nitrogen cycling in forest soils across climate gradients in Eastern China. Plant and Soil 2011, 342, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, I.; Delfosse, O.; Mary, B. Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization in Acidic, Limed and Calcareous agricultural soils: Apparent and Actual effects. Soil Biology & Biochemistry - SOIL BIOL BIOCHEM 2007, 39, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Han, Y.; Roelcke, M.; Nieder, R.; Car, Z. Sources of nitrous and nitric oxides in paddy soils: Nitrification and denitrification. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2014, 26, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasinghe, K.N.; Rodgers, G.A.; Jenkinson, D.S. Transformations of nitrogen fertilizers in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1985, 17, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M.S.; Stark, J.M.; Rastetter, E. CONTROLS ON NITROGEN CYCLING IN TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS: A SYNTHETIC ANALYSIS OF LITERATURE DATA. Ecological Monographs 2005, 75, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Liu, K.; Ahmed, W.; Jing, H.; Qaswar, M.; Kofi Anthonio, C.; Maitlo, A.A.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H. Nitrogen Mineralization, Soil Microbial Biomass and Extracellular Enzyme Activities Regulated by Long-Term N Fertilizer Inputs: A Comparison Study from Upland and Paddy Soils in a Red Soil Region of China. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-S.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, K.-S.; Chang, S.X.; Yoon, K.-S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Choi, W.-J. Soil and plant nitrogen pools in paddy and upland ecosystems have contrasting δ15N. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2015, 51, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, R.; Rengasamy, P.; Marschner, P. Effect of exchangeable cation concentration on sorption and desorption of dissolved organic carbon in saline soils. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 465, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.C.; Nico, P.S.; Bone, S.E.; Marcus, M.A.; Pegoraro, E.F.; Castanha, C.; Kang, K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Torn, M.S.; Peña, J. Association between soil organic carbon and calcium in acidic grassland soils from Point Reyes National Seashore, CA. Biogeochemistry 2023, 165, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minick, K.J.; Fisk, M.C.; Groffman, P.M. Soil Ca alters processes contributing to C and N retention in the Oa/A horizon of a northern hardwood forest. Biogeochemistry 2017, 132, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Y.L.; Schulin, R.; Nowack, B. Cu and Zn mobilization in soil columns percolated by different irrigation solutions. Environmental Pollution 2009, 157, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, D.; Yang, R.; Fu, H. Effect of land management practices on the concentration of dissolved organic matter in soil: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2019, 344, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.K.; Tavakkoli, E.; Cozzolino, D.; Banas, K.; Derrien, M.; Rengasamy, P. A survey of total and dissolved organic carbon in alkaline soils of southern Australia. Soil Research 2017, 55, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.G.; Eimers, M.C. Decreasing soil water Ca2+ reduces DOC adsorption in mineral soils: Implications for long-term DOC trends in an upland forested catchment in southern Ontario, Canada. Science of The Total Environment 2012, 427-428, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapek, B. Relationship between dissolved organic carbon and calcium and magnesium in soil water phase and their uptake by meadow vegetation / Zależność miedzy rozpuszczalnym węglem organicznym (RWO) w fazie wodnej gleby a stężeniem w niej wapnia i magnezu oraz ich pobraniem z plonem roślinności łąkowej. Journal of Water and Land Development 2013, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, M.; Wanek, W.; Hämmerle, I.; Fuchslueger, L.; Hofhansl, F.; Knoltsch, A.; Schnecker, J.; Takriti, M.; Watzka, M.; Wild, B.; et al. Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon:nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aye, N.S.; Butterly, C.R.; Sale, P.W.G.; Tang, C. Interactive effects of initial pH and nitrogen status on soil organic carbon priming by glucose and lignocellulose. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 123, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Shao, M. Accumulation of soil organic carbon in aggregates after afforestation on abandoned farmland. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2013, 49, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Liao, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F. Microbial community mediated response of organic carbon mineralization to labile carbon and nitrogen addition in topsoil and subsoil. Biogeochemistry 2016, 128, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, T.; DeCiucies, S.; Hanley, K.; Enders, A.; Woolet, J.; Lehmann, J. Microbial Community Shifts Reflect Losses of Native Soil Carbon with Pyrogenic and Fresh Organic Matter Additions and Are Greatest in Low-Carbon Soils. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2021, 87, e02555–02520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Soil management | paddy soil | maize soil |

| Number of sites (n) | 8 | 3 |

| Geophysical of landscape (elevation) | Lowland (200-400 ASL) | Lowland (200-400 ASL) |

| Age (year) | 20 | 20 |

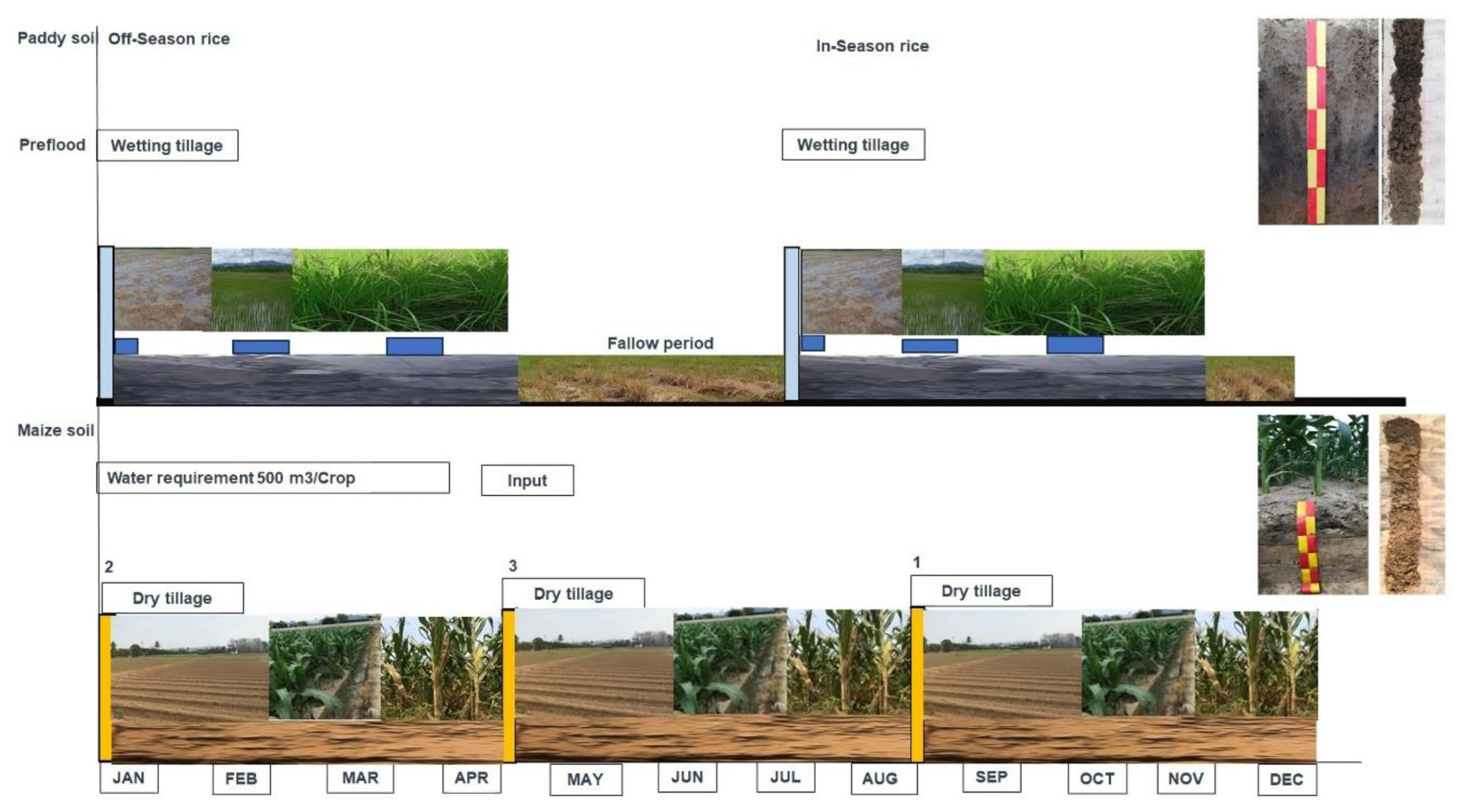

| Tillage intensity | Wetting tillage and puddled | Dry tillage and bedding |

| Irrigation | Rainfed and waterlog/paddy soil/wet and dry | Rainfed/upland condition |

| Planting intensity(time year) | 1-2 time year-1 | 3 time year-1 |

| Mineral fertilisation | mean (size) #,min- max (size) # | mean (size),min-max (size) |

| N (Kg ha -1year-1) | 61 (Low), 23-96 (Low) | 104 (Intermediate),70-137, (Intermediate) |

| P2O5 (Kg ha-1 year-1) | 27 (Intermediate), 0-56 (Low to Intermediate) | 39 (Intermediate), 0-62, (Low- Intermediate) |

| K2O (Kg ha-1 year-1) | 9 (Low), 0-26 (Low) | 18.3 (Low), 0-50 (Low) |

| N:P:K (size) # | Low: Intermediate: Low | Intermediate: Intermediate: Low |

| Crop residues management | Leave root and straw residues in the plot and plough them into the soil. | Leave maize straw residue in the plot and plough it into the soil. |

| Soil depth | POXC | WSC | HWSC | |||

| (g kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | ||||

| Paddy(n=8) | ||||||

| 0-15 | 1.05 | (0.07) | 66.45 | (5.73) | 74.25 | (5.73) |

| 15-30 | 0.63 | (0.07) | 41.20 | (3.48) | 47.75 | (3.88) |

| 30-45 | 0.42 | (0.05) | 31.20 | (2.04) | 36.50 | (2.75) |

| 45-60 | 0.39 | (0.04) | 33.70 | (2.84) | 40.00 | (3.28) |

| 60-80 | 0.34 | (0.04) | 34.20 | (3.82) | 39.50 | (4.32) |

| 80-100 | 0.30 | (0.05) | 25.80 | (4.03) | 33.60 | (4.03) |

| Mean | 0.52A | (0.06) | 38.76A | (3.66) | 45.27A | (4.00) |

| Soil depth Maize(n=3) | ||||||

| 0-15 | 0.81 | (0.07) | 34.87 | (4.06) | 42.67 | (4.06) |

| 15-30 | 0.39 | (0.07) | 20.20 | (2.45) | 28.00 | (2.45) |

| 30-50 | 0.25 | (0.02) | 12.20 | (1.00) | 15.33 | (1.05) |

| 50-60 | 0.25 | (0.02) | 16.20 | (2.24) | 14.00 | (1.00) |

| 60-80 | 0.21 | (0.02) | 16.87 | (1.20) | 12.67 | (0.67) |

| 80-100 | 0.14 | (0.00) | 16.20 | (1.55) | 12.00 | (0.00) |

| Mean | 0.34B | (0.03) | 19.42B | (2.08) | 20.78B | (1.54) |

| pH | P | K | Na | Ca | Mg | CEC | NH4+-N | NO3--N | ||||||||||

| <-------------- ---------------------------------------------- (mg kg-1)----------------------------------------------> | cmol(+) kg-1 | <---------- (mg kg-1)--------> | ||||||||||||||||

| Paddy (n=8) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0-15 | 6.82 | (0.17) | 7.34 | (0.63) | 88.41 | (2.44) | 145.76 | (7.34) | 1484.33 | (157.87) | 175.46 | (17.38) | 9.7 | (0.84) | 6.54 | (0.69) | 6.17 | (0.61) |

| 15-30 | 6.77 | (0.09 | 7.28 | (1.05) | 60.20 | (4.26) | 148.93 | (9.03) | 1499.63 | (167.40) | 205.41 | (25.42) | 10.0 | (0.91) | 6.23 | (0.74) | 4.76 | (0.63) |

| 30-45 | 6.99 | (0.08 | 3.92 | (0.33) | 60.55 | (5.43) | 155.53 | (11.33) | 1489.03 | (174.52) | 210.83 | (27.72) | 10.0 | (0.96) | 6.94 | (0.63) | 4.27 | (0.38) |

| 45-60 | 7.43 | (0.22 | 4.77 | (0.50) | 69.29 | (4.71) | 137.83 | (10.09) | 1423.80 | (156.79) | 208.29 | (24.31) | 9.6 | (0.86) | 6.33 | (0.82) | 5.17 | (0.31) |

| 60-80 | 6.95 | (0.15 | 5.28 | (0.83) | 66.14 | (5.81) | 129.95 | (10.22) | 1265.41 | (159.99) | 212.25 | (27.06) | 8.8 | (0.88) | 5.84 | (0.77) | 6.93 | (1.55) |

| 80-100 | 6.72 | (0.23 | 6.07 | (1.17) | 66.43 | (6.76) | 158.33 | (10.62) | 1371.58 | (161.79) | 194.00 | (24.20) | 9.3 | (0.89) | 7.02 | (1.02) | 5.66 | (1.18) |

| Mean | 6.95A | (0.16) | 5.77ns | (0.75) | 68.50B | (4.90) | 146.05B | (9.77) | 1422.30A | (163.06) | 201.04A | (24.35) | 9.6A | (0.33) | 6.48A | (0.78) | 5.49ns | (0.78) |

| Maize (n=3) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0-15 | 5.66 | (0.38) | 9.34 | (2.16) | 122.83 | (7.45) | 203.38 | (8.04) | 428.11 | (34.30) | 90.28 | (9.85) | 4.1 | (0.23) | 4.81 | (0.89) | 9.70 | (1.61) |

| 15-30 | 6.37 | (0.40) | 7.25 | (1.44) | 100.71 | (21.01) | 209.75 | (6.29) | 456.00 | (31.02) | 102.25 | (15.35) | 4.3 | (0.25) | 2.81 | (0.36) | 9.70 | (3.07) |

| 30-50 | 6.97 | (0.27) | 4.51 | (0.33) | 70.57 | (12.25) | 194.43 | (4.66) | 427.31 | (13.87) | 125.64 | (24.12) | 4.2 | (0.14) | 4.33 | (0.92) | 4.39 | (0.28) |

| 50-60 | 6.12 | (0.28) | 5.00 | (0.77) | 88.25 | (20.26) | 203.68 | (5.76) | 455.08 | (32.87) | 95.31 | (22.62) | 4.2 | (0.26) | 3.36 | (0.42) | 4.01 | (0.28) |

| 60-80 | 5.96 | (0.28) | 2.59 | (0.12) | 49.46 | (3.52) | 203.25 | (3.59) | 401.39 | (18.17) | 72.06 | (15.11) | 3.6 | (0.13) | 3.66 | (0.74) | 4.26 | (0.57) |

| 80-100 | 5.96 | (0.44) | 2.41 | (0.47) | 43.31 | (1.07) | 192.33 | (3.38) | 377.79 | (15.64) | 62.96 | (3.62) | 3.4 | (0.10) | 3.98 | (0.52) | 9.47 | (1.30) |

| Mean | 6.17B | (0.34) | 5.18ns | (0.88) | 79.19A | (10.93) | 201.14A | (5.28) | 424.28B | (24.31) | 91.41B | (15.11) | 4.0B | (0.54) | 3.83B | (0.64) | 6.92 | (1.18) |

| DOC:P | DOC:NO3 | P:NH4 | DOC:NH4 | DOC:Ca | DOC:Mg | DOC:SOC | ||||||||

| Paddy (n=8) | ||||||||||||||

| 0-15 | 25.36 | (4.31) | 29.65 | (4.40) | 1.16 | (0.20) | 25.86 | (2.87) | 0.11 | (0.01) | 0.98 | (0.14) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 15-30 | 17.72 | (2.63) | 26.06 | (3.62) | 1.30 | (0.21) | 18.90 | (2.32) | 0.08 | (0.01) | 0.55 | (0.05) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 30-45 | 22.09 | (2.70) | 17.60 | (1.50) | 1.98 | (0.19) | 11.34 | (1.10) | 0.06 | (0.01) | 0.46 | (0.05) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 45-60 | 18.62 | (1.84) | 16.33 | (2.25) | 1.57 | (0.21) | 16.57 | (2.52) | 0.06 | (0.01) | 0.46 | (0.05) | 0.03 | (0.00) |

| 60-80 | 20.35 | (2.70) | 19.45 | (3.41) | 1.77 | (0.35) | 15.08 | (1.46) | 0.07 | (0.01) | 0.46 | (0.05) | 0.04 | (0.00) |

| 80-100 | 14.46 | (2.40) | 14.67 | (1.74) | 1.67 | (0.24) | 11.27 | (1.56) | 0.06 | (0.01) | 0.35 | (0.04) | 0.05 | (0.01) |

| Mean | 19.77A | (2.76) | 20.63A | (2.82) | 1.58A | (0.23) | 16.50ns | (1.97) | 0.07B | (0.01) | 0.54ns | (0.07) | 0.03A | (0.00) |

| Maize (n=3) | ||||||||||||||

| 0-15 | 12.38 | (2.32) | 10.25 | (2.03) | 0.56 | (0.04) | 21.58 | (4.07) | 0.19 | (0.03) | 0.99 | (0.19) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 15-30 | 11.03 | (3.01) | 9.36 | (2.06) | 0.69 | (0.23) | 18.17 | (1.93) | 0.11 | (0.02) | 0.61 | (0.12) | 0.01 | (0.00) |

| 30-50 | 6.44 | (0.60) | 6.53 | (0.52) | 1.15 | (0.33) | 8.70 | (1.51) | 0.07 | (0.00) | 0.41 | (0.13) | 0.01 | (0.00) |

| 50-60 | 7.42 | (1.31) | 7.76 | (0.63) | 0.72 | (0.07) | 10.02 | (1.16) | 0.07 | (0.01) | 0.52 | (0.12) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 60-80 | 11.65 | (0.78) | 8.05 | (1.20) | 1.36 | (0.22) | 10.66 | (1.67) | 0.07 | (0.00) | 0.56 | (0.09) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| 80-100 | 14.44 | (2.86) | 3.31 | (0.49) | 1.79 | (0.15) | 7.77 | (1.09) | 0.08 | (0.00) | 0.46 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.00) |

| Mean | 10.56B | (1.81) | 7.54B | (1.15) | 1.04B | (0.17) | 12.82ns | (1.91) | 0.10A | (0.01) | 0.59ns | (0.12) | 0.02B | (0.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).