Submitted:

21 February 2024

Posted:

25 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

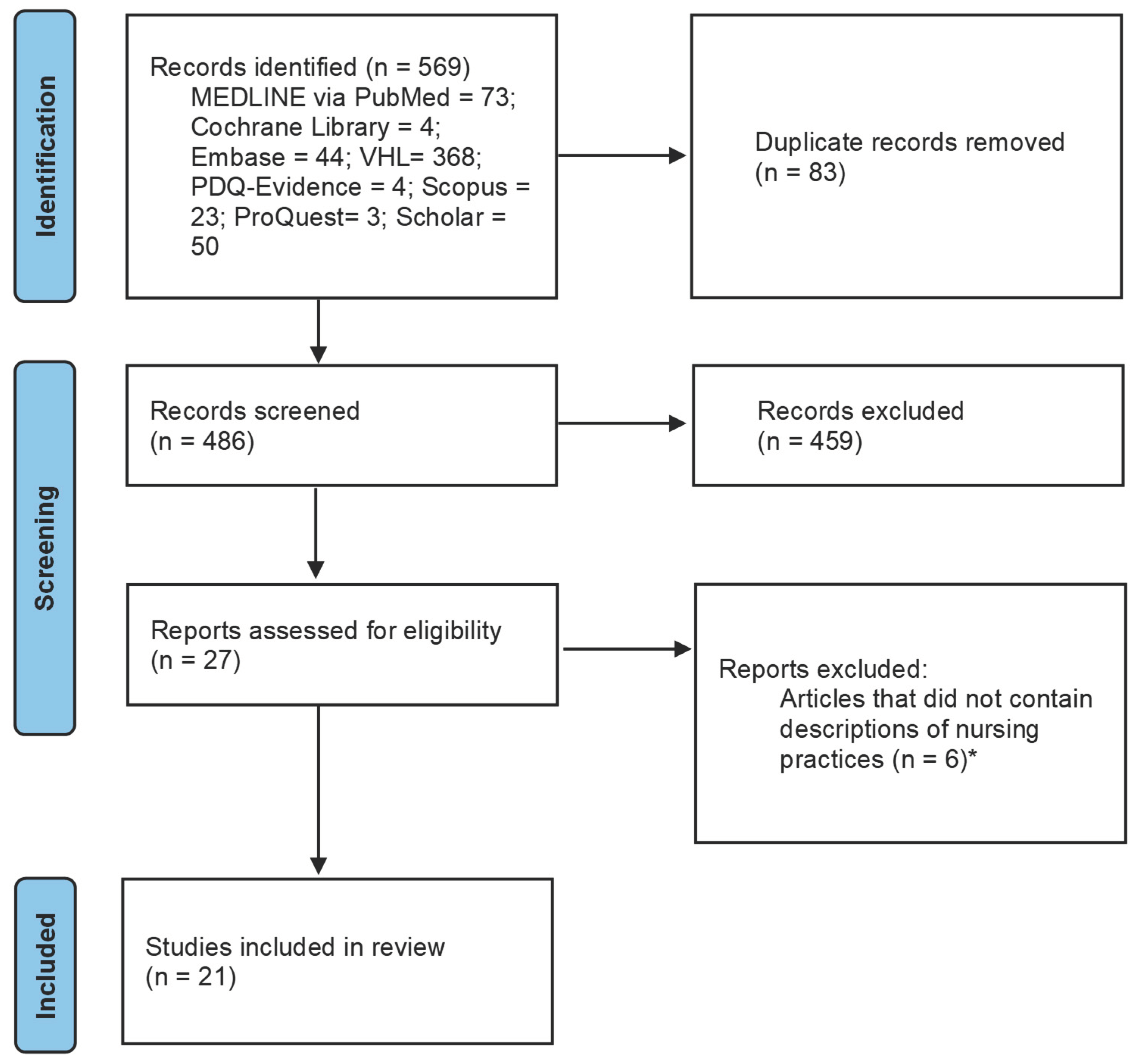

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Study/source of evidence selection

2.3. Data extraction, data analysis and presentation

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of included articles

3.2. Care practices

3.2.1. Immediate care

3.2.2. Intermediate care

3.2.3. Psychosocial care

3.2.4. Ethical care

3.3. Care management and coordination practices

3.3.1. Care coordination

3.3.2. Victim care network organization

3.3.3. Teamwork

3.3.4. Training

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Risk reduction and emergency preparedness: WHO six-year strategy for the health sector and community capacity development. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. 22p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43736 (accessed on 20 12 2023).

- Ljunggren, F.; Moen, I.; Rosengren, K. How to be prepared as a disaster nursing: an interview study with nursing students in indonesia. HDQ 2019, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Desasters. (2023). 2022 Disasters in numbers. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/cred-crunch-newsletter-issue-no-70-april-2023-disasters-year-review-2022 (accessed on 20 12 2023).

- Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Pant, P.R.; Sathian, B.; Tuladhar, G. Public Health, Prevention and Health Promotion in Post-Earthquake Nepal. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardagh, M.W.; Richardson, S.K.; Robinson, V.; Than, M.; Gee, P.; Henderson, S.; Khodaverdi, L.; McKie, J.; Robertson, G.; Schroeder, P.P.; Deely, J.M. The initial health-system response to the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, in February, 2011. Lancet 2012, 379, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catton, H.; Stewart, D.; Burton, E.; White, J.; Salmon, M.; McClelland, A. Santé pour tous: Soins infirmiers, santé mondiale et couverture sanitaire universelle. ICN: Genève, Suisse, 2019. Available from: http://aispn.be/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ICN_Design_FR-1.pdf (accessed on 20 12 2023).

- Nations Unies. Des hôpitaux à l’abri des catastrophes. NU: Genève, Suisse, 2009. 28p. Available from : https://www.unisdr.org/2009/campaign/pdf/wdrc-2008-2009-information-kit-french.pdf (accessed on 21 12 2023).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; Clark, J.; Clarke, M.; Cook, D.; D’Amico, R.; Deeks, J.J.; Devereaux, P.J.; Dickersin, K.; Egger, M.; Ernst, E.; … Tugwell, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med Clin Cases 2009, 151, 264–269. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, M.; Dawson, P. Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education: Qualitative synthesis and systematic review. Med Educ 2013, 47, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, A.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Najafi, B.; Saidi, H.; Moradi, K. Reflecting on the challenges encountered by nurses at the great Kermanshah earthquake: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs 2021, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat Camacho, N.; Karki, K.; Subedi, S.; von Schreeb, J. International Emergency Medical Teams in the Aftermath of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med 2019, 34, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, R.M.; Berryman, E. Nursing and nursing education in Haiti. Nurs Outlook 2012, 60, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, S. A. Faheem, Z. A., Somani, R. K. Role of community health nurse in earthquake affected areas. J Pak Med Assoc 2012, 62, 1083–1086. Available from: https://www.jpma.org.pk/article-details/3720 (accessed on 20 12 2023).

- Kalanlar, B. A PRISMA-driven systematic review for determination of earthquake and nursing studies. Int Emerg Nurs 2021, 59, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, H.; Koido, Y.; Kawashima, Y.; Kohayagawa, Y.; Misaki, M.; Takahashi, A.; Kondo, Y.; Chishima, K.; Toyokuni, Y. Consideration of Medical and Public Health Coordination—Experience from the 2016 Kumamoto, Japan Earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med 2019, 34, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Turale, S.; Stone, T.E.; Petrini, M. A grounded theory study of “turning into a strong nurse”: Earthquake experiences and perspectives on disaster nursing education. Nurse Educ Today 2015, 35, e43–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, Y.; Kato, I.; Ohkawa, T. Sustaining Power of Nurses in a Damaged Hospital During the Great East Japan Earthquake. J Nurs Sch 2019, 51, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrabadi, A.N.; Naji, H.; Mirzabeigi, G.; Dadbakhs, M. Earthquake relief: Iranian nurses’ responses in Bam, 2003, and lessons learned. Int Nurs Ver 2007, 54, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, P.K.; George, E.K.; Raymond, N.; Lewis-OʼConnor, A.; Victoria, S.; Lucien, S.; Peters-Lewis, A.; Hickey, N.; Corless, I.B.; Tyer-Viola, L.; Davis, S.M.; Barry, D.; Marcelin, N.; Valcourt, R. Orphans and at-risk children in Haiti: Vulnerabilities and human rights issues post-earthquake. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2012, 35, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, S.; Ardagh, M.; Grainger, P.; Robinson, V. A moment in time: Emergency nurses and the Canterbury earthquakes. Int Nurs Ver 2013, 60, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.A.; Abdi, A.; Akbari, F.; Moradi, K. Nurses’ professional competences in providing care to the injured in earthquakes: A qualitative study. Educ Health Promot 2020, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Atogami, F.; Nakamura, Y.; Kusaka, Y.; Yoshizawa, T. Committed to working for the community: Experiences of a public health nurse in a remote area during the Great East Japan Earthquake. Health Care Women Int 2015, 36, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrymgeour, G.C.; Smith, L.; Maxwell, H.; Paton, D. Nurses working in healthcare facilities during natural disasters: A qualitative enquiry. Int Nurs Rev 2020, 67, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, F.-J.; Liao, Y.-C.; Chan, S.-M.; Duh, B.-R.; Gau, M.-L. (2002). The impact of the 9-21 earthquake experiences of Taiwanese nurses as rescuers. Soc Sci Med 2002, 55, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloand, E.; Ho, G.; Klimmek, R.; Pho, A.; Kub, J. (2012). Nursing children after a disaster: A qualitative study of nurse volunteers and children after the Haiti earthquake. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2012, 17, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, H.; Hamid, A.Y.S.; Mulyono, S.; Putri, A.F.; Chandra, Y.A. (2019). Expectations of survivors towards disaster nurses in Indonesia: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci 2019, 6, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenji, Z.; Turale, S.; Stone, T.E.; Petrini, M.A. (2015). Chinese nurses’ relief experiences following two earthquakes: Implications for disaster education and policy development. Nurse Educ Pract 2015, 15, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.E.; Turale, S.; Stone, T.; Petrini, M. (2015). Disaster nursing skills, knowledge and attitudes required in earthquake relief: Implications for nursing education. Int Nurs Rev 2015, 62, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-N.; Xiao, L.D.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Zhu, J.-C.; Arbon, P. (2010). Chinese nurses’ experience in the Wenchuan earthquake relief. Int Nurs Ver 2010, 57, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Hirano, K.; Sato, M.; Abe, A.; Uebayashi, M.; Kishi, E.; Sato, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Nakaita, I.; Fukushima, F. (2014). Activities and health status of dispatched public health nurses after the great East Japan earthquake. Public Health Nurs 2014, 31, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda Neto, M.V. de, Rewa, T.; Leonello, V.M.; M. Oliveira, M.A. de C. Advanced practice nursing: A possibility for Primary Health Care? Rev Bras Enferm 2018, 71, 716–721. [CrossRef]

- Olímpio, J. de A.; Araújo, J.N. de M.; Pitombeira, D.O.; Enders, B.C.; Sonenberg, A.; Vitor, A.F. Prática Avançada de Enfermagem: Uma análise conceitual. Acta Paul Enferm 2016, 31, 647–680. [CrossRef]

- Deelstra, A.; Bristow, D.N. Methods for representing regional disaster recovery estimates: modeling approaches and assessment tools for improving emergency planning and preparedness. Nat Hazards 2023, 117, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, P. N., Dami, F., Frei, O., Niquille, M., Pasquier, M., Vallotton, L., Yersin, B. Médecine d’urgence préhospitalière. Available from: https://files.medhyg.ch/LIVRES_MH/MUP/Mises_a_jour_et_erratum_2016.pdf (accessed on 21 12 2023).

- Bélanger, E. La pratique d’infirmières ayant participé à une mission humanitaire en Haïti suite au séisme de 2010 au sein d’une organisation non gouvernementale. Master in Sciences infirmières, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada, 2013. Available from: https://doi.org/1866/12810 (accessed on 21 12 2023).

- Comité international de la Croix-Rouge. Guide de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge sur l’engagement communautaire et la redevabilité (CEA). CICR: Genève, Suisse, 2021. Available from: https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/IFRC-CEA-GUIDE-francais-LR-PDF.pdf (accessed on 21 12 2023).

- Maret, L. Le rôle infirmier lors d’un évènement majeur dans un service d’urgences. Bachelor of Nursing, Haute Ecole de Santé Valais, Sion, Suisse, 2018. Available from: https://sonar.ch/global/documents/317174 (accessed on 21 12 2023).

- DeBerry. (2020). Globally recognized disaster nurse training needs. Bachelor of Nursing, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2020. Available from: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/348509/Thesis_DeBerry_Siltanen.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 21 12 2023). 2023.

- International Council of Nurses. Compétences de base pour les soins infirmiers en cas de catastrophe version 2.0. ICN: Genève, Suisse, 2019. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/2023-04/ICN_Disaster-Comp-Report_FR_WEB.pdf (accessed on 21 12 2023).

| Author, year | Study design and method | Objective | Main practices identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdi et al., 2021 [11] | Qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 nurses involved in providing care to those injured in the Kermanshah earthquake. After transcription, conventional content analysis was performed using the Granheim and Landman approach. | Discuss the challenges faced by nurses in caring for victims of the Kermanshah earthquake in 2017. |

• Prioritize victims; • Coordinate and organize regional field hospitals; • Efficiently use financial and human resources; • Use helicopters to rescue survivors; • Check consistency between ordered medications and supplied items; • Have a good command unit; • Assign roles between; institutions/organizations; • Manage volunteers; • Manage nurses’ physical and mental health; • Manage uniform use, identification and distinction for professionals; • Manage internal communication; • Manage material and human resources; • Promote training in patient transport protocols, safety and flight physiology. |

| Amat Camacho et al., 2018 [12] | Retrospective, documentary-based descriptive study. A search was carried out on PubMed and Google on International Emergency Medical Teams (I-EMT) using the STARLITE methodological principles (sampling strategy, type of study, approaches, year range, limits, inclusion and exclusions, terms used, electronic sources). Based on the results, the authors selected studies that addressed the timing and activities of I-EMT during the 2015 earthquake in Nepal and were included in the study. | Describe the characteristics, timing and activities carried out by I-EMTs deployed in Nepal following the 2015 earthquake and assess their adherence to the WHO I-EMT | • Treat wounds, consultation, admission, surgery; • Manage teams; • Prioritize vulnerable groups (older adults, pregnant women, patients with chronic illnesses, major trauma cases); • Make it easier for nurses to share information and obtain information about their own families; • Facilitate first aid to victims; • Manage daily reports • Manage language barriers; • Manage national treatment protocols and I-EMT treatment protocols. |

| Garfield & Berryman, 2011 [13] | Qualitative descriptive study that sought to describe the situation of nursing education in Haiti. | Not reported | • Prioritize care for vulnerable groups (older adults, pregnant women, patients with chronic illnesses); • Prepare doctors and nurses who work in Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs); • Enable the implementation of a nursing education program; • Promote the creation of boards of voluntary organizations that provide health services. |

| Gulzar et al., 2012 [14] | Qualitative evaluative study, using the planning cycle structure as a theoretical basis. Focus groups and in-depth interviews were carried out and analyzed (content analysis) and categorized thematically. | Describe the experience of interventions carried out by community health nurses through a guided framework (assessment, planning, implementation and assessment components) | • Establish disaster management protocols; • Facilitate information sharing (national and international); • Reorganize prenatal and postnatal services and delivery rooms; • Vaccinate nurses against hepatitis. |

| • Provide continuing education in areas such as hepatitis, skin problems, respiratory infections in children and health problems; • Train on cold chain maintenance; • Offer educational modules on hygiene and health. | |||

| Kalanlar et al., 2021 [15] | A review was carried out in five databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science), using the keywords “earthquake” and “nursing” for studies published between 2010 and 2020. Of the 665 articles identified, 19 were included in the review. | Establish a general framework of evidence on earthquakes and nursing and develop recommendations for future studies in this field. | • Respect intercultural differences in care provision • Resolve conflicts and ethical dilemmas; • Promote psychosocial support programs to protect nurses’ health and well-being; • Facilitate transportation of large numbers of victims; • Manage emergencies and interventions in psychological crises; • Facilitate obtaining information about victims and families, including from nurses themselves; • Promote continuing education; • Provide training program, including and assessing ethical issues related to disasters. |

| Kondo et al., 2019 [16] | Qualitative descriptive study. All communication records made in July 2016 in Kumamoto, Japan were assessed. After reading the records, the main recorded events were selected. | Identify improvements in disaster medical operations from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (Kumamoto prefecture, Japan) and extract further lessons learned to prepare for expected future large earthquakes. | • Deploy medical rescue services and teams; • Manage teams; • Check the status of disaster-affected hospitals using the Emergency Medical Information System • Monitor evacuation shelters; • Watch hospital operations; • Coordinate the transfer of patients admitted to damaged hospitals; • Use helicopters to rescue survivors; • Provide healthcare in evacuation shelters; • Provide healthcare at the rescue site and provide logistical support; • Ensure physical and mental health conditions for teams; • Share information between emergency departments (national and international); • Create phone number lists for all disaster relief medical teams; • Develop a standardized system for maintaining medical records. |

| Li et al., 2015 [17] | Qualitative study that carried out in-depth interviews with 15 nurses from five different hospitals. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed according to Grounded Theory as a theoretical approach. | Explore Chinese nurses’ earthquake experiences and develop a substantive theory of seismic disaster nursing that will help inform the future development of disaster nursing education. | • Develop critical thinking and adaptability; • Facilitate management of mutual vulnerability and safety between professionals and victims; • Facilitate good collaboration between teams; • Facilitate first aid, professional psychological trauma counseling and psychological support; • Facilitate specialized training in trauma, emergency, major surgery, sterilization and wound healing equipment as well as psychological and mental health knowledge. |

| Nakayama et al., 2019 [18] | Qualitative descriptive study. A Japanese methodology called Katarai (a form of group interview) was used, consisting of 11 nurses. After the Katarai, two in-depth interviews were carried out with head nurses who worked during earthquake. | Describe the experiences of nurses working in a psychiatric hospital in Fukushima prefecture during the Great East Japan Earthquake and explore what sustained nurses while working in the damaged hospital. | • Assist psychiatric patients; • Use protective measures to evacuate and ensure survivor safety; • Use infection prevention and control measures; • Resolve conflicts and ethical dilemmas; • Facilitate the transfer of patients from one hospital to another; • Manage human waste and other waste. |

| Nasrabadi et al., 2003 [19] | Qualitative study carried out with 13 participating nurses. Data were obtained through serial semi-structured interviews and analyzed using the latent content method. | Explore the experiences of Iranian registered nurses in disaster relief in the 2003 Bam earthquake in Iran. | • Establish disaster management protocols; • Facilitate organization in the workplace; • Promote continuing education; • Facilitate training programs. |

| Nicholas et al., 2012 [20] | Case report on pediatric care in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. | Discuss the complex interplay between an environmental emergency and the increasing risk factors and human rights issues for the pediatric population in Haiti. | • Prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV through education; • Prevent sexual violence, especially among vulnerable women and children with HIV/AIDS; • Treat sexually transmitted infections; • Prioritize care for vulnerable groups (children, older adults, pregnant women, patients with chronic diseases including HIV, major cases of trauma); • Facilitate adherence to blood safety programs. |

| Richardson et al., 2013 [21] | Qualitative study that conducted interviews with nurses who worked in the 2010 earthquake in New Zealand | Describe the impact of the Canterbury, New Zealand, earthquakes on Christchurch Hospital and emergency nurses’ experiences during this period. | • Distribute services and equipment to healthcare teams; • Facilitate good collaboration between teams; • Use informal communication (such as telephone contact, television news, and the Internet) to understand and report events as they are presented; • Support the implementation of coordinated emergency plans, with frequent review, practice and education; • Perform patient tracking and keep clinical documentation up to date. |

| Rezaei et al., 2020 [22] | Qualitative descriptive study that carried out semi-structured interviews with 16 nurses involved in providing care to those injured in the earthquake in Kermanshah, Iran. Data were analyzed using the Graneheim and Lundman approach. | Identify professional skills needed by nurses to provide care to those injured by earthquake. | • Develop a sense of observation and monitoring; • Develop skills in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), prevention of hemostasis, dressings, safety, manual handling and emergency management, intravenous insertion, observation, monitoring and screening of victims; • Maintain patient confidentiality; • Help nurses to be creative in providing care (soft skills); • Facilitate effective communication between nurses, survivors and the healthcare team; • Facilitate adaptation to the traumatic situation. |

| Sato et al., 2015 [23] | Qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with nurses who had worked during the earthquake in Japan in 2011. After transcription, content analysis was carried out according to the Hammersley & Atkinson (2007) framework. | Describe the experiences of a local government public health nurse who worked in an area affected after the Great East Japan Earthquake. | • Manage volunteers; • Value mutual respect; • Facilitate good internal communication. |

| Scrymgeour et al., 2020 [24] | Pluralistic qualitative research and inductive thematic analysis were carried out. 15 interviews were carried out with nurses who worked in hospitals and institutions for older adults during earthquakes between 2010 and 2015 in New Zealand or Australia. Data analysis used the methodological precepts of Braun & Clarke (2006), in which inductive coding was carried out by the researcher. | Explore the factors that influence nurses’ resilience and adaptive capacity during a critical incident caused by a natural disaster. | • Generate responsibility of the nursing team towards families and survivors; • Promote continuing education; • Coordinate patient care; • Ensure patient and team safety; • Develop personal skills. |

| Shih et al., 2002 [25] | Qualitative descriptive study. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with five highly experienced nurses. After transcription, content analysis was carried out. | Compare the impacts of rescue experiences on Taiwanese nurses and nurses who worked as first responders after the September 21 earthquake. | • Help identify factors that impede provision of vital care; • Monitor the population’s health status; • Advise play therapy for children; • Detect psychological problems; • Carry out psychosocial interventions after the earthquake; • Maintain daily activities; • Assess and manage health problems; • Provide medicines; • Treat wounds; • Provide spiritual care; • Establish disaster management protocols; • Ensure physical and mental health conditions for teams; • Facilitate healthcare missions in mountainous regions. |

| Sloand et al., 2012 [26] | Qualitative descriptive study. Conducted in-depth interviews with 12 volunteer nurses who worked during the Haiti earthquake in 2010. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed with the support of NVivo9. | Explore the experiences of volunteer nurses caring for children following the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti. | • Communicate affectionately with children; • Incorporate games into child care; • Promote resilience to traumatic shocks. |

| Susanti et al., 2019 [27] | Qualitative descriptive study. Three focus groups were held with 21 survivors and in-depth interviews with three community leaders were held. After transcription, content analysis was carried out using the theoretical precepts of Graneheim & Lundman (2004). | Explore survivors’ expectations of disaster nurses. | • Carry out health exams or tests; • Administer medications; • Support pregnancy testing; • Proactively carry out home visits; • Treat equitably groups recognized as vulnerable, such as pregnant women, breastfeeding women, older adults, people with disabilities and people suffering from trauma and chronic illnesses, such as hypertension and diabetes, and children; • Respect and integrate cultural values in provision of care; • Distribute services and equipment to healthcare teams; • Establish disaster management protocols; • Ensure physical and mental health conditions for teams; • Assess and monitor the activities carried out. |

| Wenji et al., 2014 [28] | Qualitative study that conducted interviews with 12 nurses in China. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed in light of the theoretical framework of narrative methods. | Describe the experiences of Chinese nurses who worked in disaster relief after the Wenchuan and Yushu earthquakes and their views on future disaster nursing education/training programs. | • Establish disaster management protocols; • Distribute teams and services; • Ensure minimum physical and mental health conditions for work teams; • Facilitate organization in the workplace; • Help nurses adapt to environmental conditions; • Support healthcare professionals in the field of mental health; • Manage resources (water, food) and medicines; • Promote continuing education. |

| Yan et al., 2015 [29] | Descriptive study that applied a questionnaire to 38 Chinese hospitals, obtaining 89 valid and analyzed responses. The means and standard deviation of the quantitative data from the questionnaire were calculated using SPSS 20.0. Qualitative data were analyzed by content analysis using the Holloway and Wheeler (2013) framework. | Explore the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required by registered nurses from across China who worked after three major earthquakes to try to determine future disaster nursing education requirements. | • Develop skills in hemorrhage control, CPR, airway management, shock management, debridement, dressings, bandages, bandage fixation and safety; • Understand the stress and pain reactions of the nursing team; • Teach ethics to nurses. |

| Yang et al., 2010 [30] | Qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 10 nurses. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed according to Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics. | Provide an understanding of how Chinese nurses acted in response to the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. | • Develop nurses’ assessment and clinical judgment skills, especially in terms of in-depth knowledge about wounds and infections; • Facilitate screening and identify the most urgent needs; • Discuss in a group to identify and report early signs and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder; • Promote training sessions; • Hand over information leaflets; • Promote continuing education; • Promote the improvement of nurses’ managerial and organizational skills. |

| Yokoyama et al., 2014 [31] | Quantitative descriptive study. A questionnaire was sent between December 2012 and January 2013 to nurses who worked during the Great East Japan Earthquake. A total of 1,640 questionnaires were received. Quantitative variables were statistically analyzed using SPSS 20.0. For qualitative variables (subjective well-being, bad mood, worsening sleep status and intense fatigue), forced entry multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with nurses’ health status. | Document the actual activities carried out by public health nurses during their discharge and their health status during and after dispatch to the three prefectures most severely affected by the earthquake. | • Enable consultations at evacuation centers; • Use infection prevention and control measures; • Organize service processes; • Manage work teams; • Ensure physical and mental health conditions for work teams; • Assess and monitor the activities carried out. |

| Thematic categories | Nursing care practices in an earthquake |

|---|---|

| Care practices |

|

| Care management and coordination practices |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).