Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

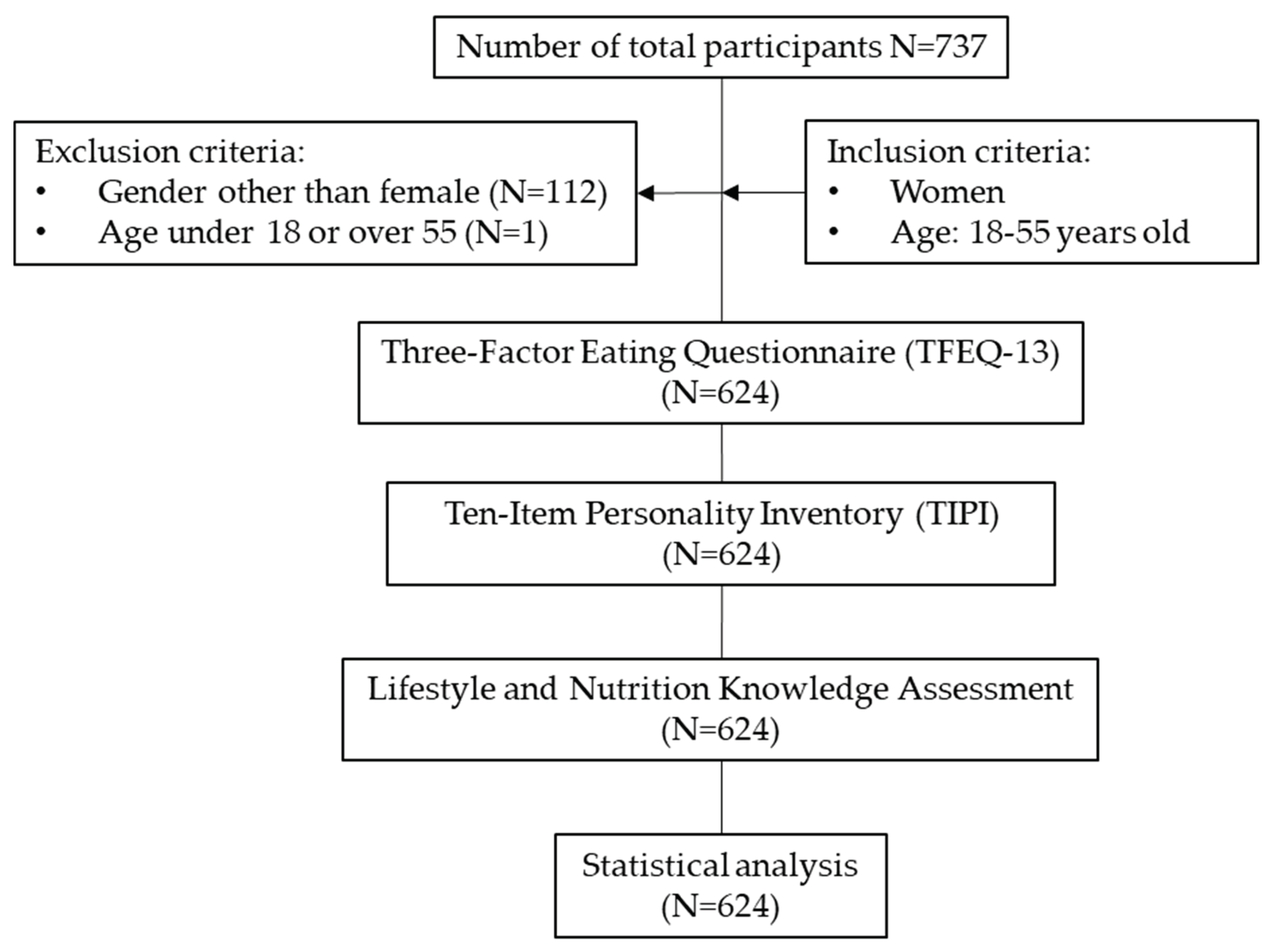

2.1. The study sample

2.2. Dietary Patterns (DPs)

2.3. Personality traits, cognitive-behavioural and emotional functioning

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dietary patterns

3.2. Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) results

3.3. Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-13) results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Sugar Consumption 2023/24 | Statista Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/249681/total-consumption-of-sugar-worldwide/ (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Statystyczny, G.U. Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski / Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland. 2022.

- WHO Calls on Countries to Reduce Sugars Intake among Adults and Children Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2015-who-calls-on-countries-to-reduce-sugars-intake-among-adults-and-children (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Lobstein, T.; Jackson-Leach, R.; Powis, J.; Brinsden, H.; Gray, M. World Obesity Atlas 2023. 2023.

- Rippe, J.M.; Angelopoulos, T.J. Sugars, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease: Results from Recent Randomized Control Trials. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Chabot, C.; Heba, A.C.; Kökten, T.; Caron, B.; Hansmannel, F.; Dreumont, N.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Quilliot, D.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Sugars and Gastrointestinal Health. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, 1912-1924.e7. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.R.; Zehra, A.; Ramirez, V.; Wiers, C.E.; Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J. Impact of Sugar on the Body, Brain, and Behavior. Frontiers in Bioscience - Landmark 2018, 23, 2255–2266. [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The Role of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in the Global Epidemics of Obesity and Chronic Diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 205. [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Magenes, V.C.; Vincenti, A.; Comola, G.; Beretta, A.; Di Napoli, I.; Zuccotti, G. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Metabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Lonnie, M.; Wadolowska, L.; Frelich, A. “Cutting down on Sugar” by Non-Dieting Young Women: An Impact on Diet Quality on Weekdays and the Weekend. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.; Chaaya, N.; Beecher, K.; Ali, S.A.; Belmer, A.; Bartlett, S. The Impact of Sugar Consumption on Stress Driven, Emotional and Addictive Behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 103, 178–199. [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.; Siegrist, M. Does Personality Influence Eating Styles and Food Choices? Direct and Indirect Effects. Appetite 2015, 84, 128–138. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.M.; Ceresa, A.; Buoli, M. The Association Between Personality Traits and Dietary Choices: A Systematic Review. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 1149. [CrossRef]

- Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M.; Jaarsma, A.D.C.; Scherpbier, A.J.J.A.; van Beukelen, P.; Demerouti, E. The Role of Personal Resources in Explaining Well-Being and Performance: A Study among Young Veterinary Professionals. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2014, 23, 190–202. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G.; Żelazko, A.; Rogalska, A.; Nowak, D.; Pawlas, K.; Badanie, P.K. Badanie Zachowań Zdrowotnych i Osobowości Typu D Wśród Studentek Dietetyki. Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu 2016, 22, 129–134. [CrossRef]

- Posadzki, P.; Stockl, A.; Musonda, P.; Tsouroufli, M. A Mixed-Method Approach to Sense of Coherence, Health Behaviors, Self-Efficacy and Optimism: Towards the Operationalization of Positive Health Attitudes. Scand J Psychol 2010, 51, 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Zygfryd.; Ogińska-Bulik, Nina. Zasoby Osobiste i Społeczne Sprzyjające Zdrowiu Jednostki. 2003.

- Dosedlová, J.; Klimusová, H.; Burešová, I.; Jelínek, M.; Slezáčková, A.; Vašina, L. Optimism and Health-Related Behaviour in Czech University Students and Adults. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015, 171, 1051–1059. [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Hirsch, J.K. Big Five Traits, Affect Balance and Health Behaviors: A Self-Regulation Resource Perspective. Personality and Individual Differences 2015, 87, 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Kampov-Polevoy, A.B.; Ziedonis, D.; Steinberg, M.L.; Pinsky, I.; Krejci, J.; Eick, C.; Boland, G.; Khalitov, E.; Crews, F.T. Association Between Sweet Preference and Paternal History of Alcoholism in Psychiatric and Substance Abuse Patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003, 27, 1929–1936. [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, J.L. Sweet Preference, Sugar Addiction and the Familial History of Alcohol Dependence: Shared Neural Pathways and Genes. J Psychoactive Drugs 2010, 42, 147–151. [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Galinski, G.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Bronkowska, M.; Dlugosz, A.; Loboda, D.; Wyka, J. Reproducibility of a Questionnaire for Dietary Habits, Lifestyle and Nutrition Knowledge Assessment (KomPAN) in Polish Adolescents and Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- 23. Zespół Behawioralnych Uwarunkowań Żywienia Komitet Nauki o Żywieniu Człowieka Polskiej Akademii Nauk Kwestionariusz Do Badania Poglądów i Zwyczajów Żywieniowych Oraz Procedura Opracowania Danych. Komitet Nauki o Żywieniu Człowieka Polskiej Akademii Nauk 2014, 3–20.

- Bykowska-Derda, A.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Kaluzna, M.; Ruchala, M.; Ziemnicka, K. Diet Quality Scores in Relation to Fatness and Nutritional Knowledge in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Case-Control Study. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, 3389–3398. [CrossRef]

- Bykowska-Derda, A.; Kałużna, M.; Garbacz, A.; Ziemnicka, K.; Ruchała, M.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M. Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 799. [CrossRef]

- Rosner: Fundamentals of Biostatistics - Google Scholar Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Fundamentals+of+Biostatistics&author=Rosner,+B.&publication_year=2011 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstem, A.R. A Simulation Study of the Number of Events per Variable in Logistic Regression Analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [CrossRef]

- Dzielska, A.; Mazur, J.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A.; Kołoło, H. Adaptacja Polskiej Wersji Kwestionariusza Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-13) Wśród Młodzieży Szkolnej w Badaniach Populacyjnych. Probl Hig Epidemiol 2009, 90, 362–369.

- Sorokowska A., Słowińska A., Zbieg A., Sorokowski P. Polska Adaptacja Testu Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) – TIPI-PL – Wersja Standardowa i Internetowa. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270449357_Polska_adaptacja_testu_Ten_Item_Personality_Inventory_TIPI_-_TIPI-PL_-_wersja_standardowa_i_internetowa (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Dzielska, A.; Mazur, J.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A.; Kołoło, H. Adaptacja Polskiej Wersji Kwestionariusza Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-13) Wśród Młodzieży Szkolnej w Badaniach Populacyjnych. Probl Hig Epidemiol 2009, 90, 362–369.

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to Measure Dietary Restraint, Disinhibition and Hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985, 29, 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains. J Res Pers 2003, 37, 504–528. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Four Ways Five Factors Are Basic. Personality and Individual Differences 1992, 13, 653–665. [CrossRef]

- Sample Size Calculator Available online: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=98&ci=5&pp=50&ps=9479673&x=Calculate (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- StatSoft Polska – Lider w Analityce Danych Available online: https://www.statsoft.pl/ (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Singh, P. Conscientiousness Moderates the Relationship between Neuroticism and Health-Risk Behaviors among Adolescents. Scandinavian journal of psychology 2022, 63, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Maćkowska, P.; Basińska, M.A. Osobowościowe Korelaty Zachowań Zdrowotnych u Osób z Cukrzycą Typu 1 i Chorobą Gravesa-Basedowa. 2010, 11, 39–45.

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gębski, J.; Kobylińska, M. Food Involvement, Eating Restrictions and Dietary Patterns in Polish Adults: Expected Effects of Their Relationships (LifeStyle Study). Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 1200 2020, 12, 1200. [CrossRef]

- Galinski, G.; Lonnie, M.; Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Babicz-Zielinska, E. Self-Reported Dietary Restrictions and Dietary Patterns in Polish Girls: A Short Research Report (GEBaHealth Study). Nutrients 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Drapeau, V.; Provencher, V.; Lemieux, S.; Després, J.P.; Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A. Do 6-y Changes in Eating Behaviors Predict Changes in Body Weight? Results from the Québec Family Study. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2003, 27, 808–814. [CrossRef]

- Giudici, K.V.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Lairon, D.; Bénard, M.; Hercberg, S.; Bellisle, F.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Péneau, S. Cognitive Restraint and History of Dieting Are Negatively Associated with Organic Food Consumption in a Large Population-Based Sample of Organic Food Consumers. Nutrients 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, A.E. The Sweet Taste of Gratitude: Feeling Grateful Increases Choice and Consumption of Sweets. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2015, 25, 561–576. [CrossRef]

- Fuente González, C.E.; Chávez-Servín, J.L.; De La Torre-Carbot, K.; Ronquillo González, D.; Aguilera Barreiro, M.D.L.Á.; Ojeda Navarro, L.R. Relationship between Emotional Eating, Consumption of Hyperpalatable Energy-Dense Foods, and Indicators of Nutritional Status: A Systematic Review. Journal of Obesity 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Człapka-Matyasik, M.; Ast, K. Total Antioxidant Capacity and Its Dietary Sources and Seasonal Variability in Diets of Women with Different Physical Activity Levels. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2014, 64, 267–276. [CrossRef]

- Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Gramza-Michalowska, A. The Total Dietary Antioxidant Capacity, Its Seasonal Variability, and Dietary Sources in Cardiovascular Patients. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 292. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, D.; Rešetar, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Bykowska-Derda, A.; Kolay, E.; Stelcer, B.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J. Changes in Diet Quality and Its Association with Students’ Mental State during Two COVID-19 Lockdowns in Croatia. Nutrition and health 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lester, D. Depression, Suicidal Ideation and the Big Five Personality Traits. Austin Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Black, C.N.; Bot, M.; Scheffer, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Is Depression Associated with Increased Oxidative Stress? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 164–175. [CrossRef]

- Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Gut, P. A Preliminary Study Investigating the Effects of Elevated Antioxidant Capacity of Daily Snacks on the Body’s Antioxidant Defences in Patients with CVD. Applied Sciences 2023, Vol. 13, Page 5863 2023, 13, 5863. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, M.; Xie, M.; Yang, Y.; Xue, F.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Jia, N.; et al. Protective Role of Antioxidant Supplementation for Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Journal of Affective Disorders 2023, 323, 264–279. [CrossRef]

- Zujko, M.E.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Witkowska, A.M.; Cicha-Mikołajczyk, A.; Zujko, K.; Drygas, W. Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity—A New Indicator of Healthy Diet Quality in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Polish Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zujko, M.E.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Drygas, W.; Cicha-mikołajczyk, A.; Zujko, K.; Szcześniewska, D.; Kozakiewicz, K.; Witkowska, A.M. Dietary Habits and Dietary Antioxidant Intake Are Related to Socioeconomic Status in Polish Adults: A Nationwide Study. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number of total participants N=624 | |||

| Study sample | ||||

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| Weight (kg) | 61,0 | 10,3 | 41,0 | 104,0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21,8 | 3,4 | 15,6 | 37,5 |

| Age (years) | 22,7 | 4,5 | 18 | 54 |

| BMI interpretation: | n (%) | |||

| → Underweight (<18,5 kg/m2) | 73 (12) | |||

| → Normal weight (>=18,5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2) | 459 (73) | |||

| → Overweight (>=25 kg/m2 and <30kg/m2) | 72 (12) | |||

| → Obesity class I (>=30 kg/m2 and <35kg/m2) | 17 (3) | |||

| → Obesity class II (>=35 kg/m2 and <40kg/m2) | 3 (0) | |||

| → Obesity class III (>=40kg/m2) | 0 (0) | |||

| Education level: | n (%) | |||

| Upper secondary | 388 (62) | |||

| BSc | 186 (30) | |||

| MSc | 50 (8) | |||

| Major of study: | n (%) | |||

| Medical (e.g. medicine, midwifery, physiotherapy and related) | 117 (19) | |||

| Nutrition | 119 (19) | |||

| Food technology | 13 (2) | |||

| Humanities and related | 80 (13) | |||

| Psychology/pedagogy and related | 132 (21) | |||

| Technical (e.g. polytechnics and related) | 42 (7) | |||

| Economics and related | 121 (19) | |||

| Place of residence: | ||||

| City >100,000 inhabitants | 300 (48) | |||

| City 20-100,000 inhabitants | 84 (13) | |||

| City <20,000 inhabitants | 74 (12) | |||

| Village | 166 (27) | |||

| Age: | ||||

| 18-26 (years) | 577 (93) | |||

| 27-35 (years) | 27 (4) | |||

| 36-44 (years) | 12 (2) | |||

| 45-54 (years) | 8 (1) | |||

| Housing: | ||||

| I live with family | 342 (55) | |||

| I live with a partner | 139 (22) | |||

| I live with a roommate | 92 (15) | |||

| I live alone | 51 (8) | |||

| Food Group | Products Included |

| pHDI-10 Pro-Healthy Diet Index |

(1) Wholemeal bread, (2) Buckwheat, oats, whole-wheat pasta, (3) Milk, (4) Fermented milk drinks, (5) Cottage cheese, (6) White meat, (7) Fish, (8) Legume-based foods, (9) Fruits, (10) Vegetables |

| nHDI-11 Non-Healthy Diet Index | (1) White bread and bakery products, (2) White rice, pasta, pasta (3) Fast food, (4) Fried food, (5) Butter, (6) Hard cheese, (7) Red meat, (8) Candies, (9) Sweetened carbonated and non-carbonated drinks, (10) Energy drinks, (11) Alcoholic beverages |

| sDI-7 Sugar diet index |

(1) Fruits, (2) Fruit juices, (3) Candies, (4) Sweetened hot drinks, (5) Sweetened carbonated or non-carbonated beverages, (6) Energy drinks, (7) Alcoholic beverages |

| SWDP | PHDP | DDP | |

| nHDI | 0.94 | -0.07 | 0.22 |

| Vegetables | -0.01 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| Fruits | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.01 |

| pHDI | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.49 |

| Cottage cheese | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.82 |

| Fermented milk drinks | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.73 |

| sDI | 0.73 | 0.39 | -0.02 |

| White bread and bakery products | 0.63 | -0.07 | -0.03 |

| Candies | 0.61 | 0.17 | -0.18 |

| Cured meat | 0.61 | -0.14 | 0.26 |

| Butter | 0.59 | -0.12 | 0.18 |

| Legumes-based foods | -0.14 | 0.58 | 0.02 |

| Hard cheese | 0.39 | -0.13 | 0.58 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Fried foods | 0.54 | -0.13 | 0.00 |

| Buckwheat, oats, wholegrain pasta | -0.21 | 0.53 | 0.34 |

| Factor loads greater than 0.50 are marked. | |||

| High Adherence to SWDP | Middle Adherence SWDP | Low Adherence to SWDP | ||||

| n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

|

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

78 | 1.02 (0.72; 1.45), p = 0.89 |

63 | 0.71 (0.50; 1.02), p = 0.06 |

85 | 1.36 (0.96; 1.91), p = 0.08 |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

108 | 0.86 (0.62; 1.20), p = 0.38 |

107 | 0.97 (0.70; 1.36), p = 0.87 |

116 | 1.19 (0.85; 1.67), p = 0.30 |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

91 | 0.66 (0.47; 0.93), p = 0.02* |

103 | 1.08 (0.77; 1.52), p = 0.65 |

113 | 1.40 (1.00; 1.97), p = 0.05 |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

91 | 1.07 (0.76; 1.50), p = 0.71 |

78 | 0.80 (0.56; 1.13), p = 0.20 |

91 | 1.17 (0.83; 1.64), p = 0.37 |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

94 | 0.86 (0.62; 1.20), p = 0.37 |

93 | 0.96 (0.69; 1.35), p = 0.82 |

104 | 1.21 (0.87; 1.70), p = 0.26 |

| Uncontrolled Eating (UE) 3rd tercile |

101 | 0.84 (0.60; 1.17), p = 0.30 |

90 | 0.70 (0.50; 0.99), p < 0.05* |

122 | 1.70 (1.21; 2.39), p < 0.01* |

| Cognitive Restraint (CR) 3rd tercile |

118 | 1.93 (1.38; 2.70), p < 0.001* |

106 | 1.59 (1.13; 2.23), p < 0.01* |

55 | 0.30 (0.21; 0.44), p < 0.001* |

| Emotional Eating (EE) 3rd tercile |

101 | 0.63 (0.45; 0.88), p < 0.01* |

113 | 1.07 (0.76; 1.51), p = 0.70 |

127 | 1.51 (1.07; 2.13), p < 0.05* |

| High Adherence to PHDP | Middle Adherence PHDP | Low Adherence to PHDP | ||||

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

85 | 1.24 (0.88; 1.76), p = 0.21 |

65 | 0.74 (0.52; 1.05), p = 0.09 |

76 | 1.09 (0.77; 1.54), p = 0.64 |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

122 | 1.25 (0.89; 1.75), p = 0.20 |

106 | 0.91 (0.65; 1.28), p = 0.60 |

103 | 0.88 (0.62; 1.23), p = 0.44 |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

127 | 1.80 (1.28; 2.53), p <0.001* |

90 | 0.72 (0.52; 1.01), p = 0.06 |

90 | 0.77 (0.55; 1.08), p = 0.13 |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

83 | 0.82 (0.58; 1.15), p = 0.25 |

87 | 1.05 (0.75; 1.48), p = 0.78 |

90 | 1.17 (0.83; 1.65), p = 0.38 |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

108 | 1.30 (0.93; 1.81), p = 0.13 |

97 | 1.02 (0.73; 1.43), p = 0.90 |

86 | 0.75 (0.53; 1.05), p = 0.10 |

| Uncontrolled Eating (UE) 3rd tercile |

126 | 1.66 (1.19; 2.34), p < 0.01* |

97 | 0.83 (0.60; 1.17), p = 0.29 |

90 | 0.72 (0.51; 1.01), p = 0.06 |

| Cognitive Restraint (CR) 3rd tercile |

67 | 0.40 (0.28; 0.58), p < 0.001* |

114 | 1.91 (1.36; 2.68), p < 0.001* |

98 | 1.25 (0.89; 1.76), p = 0.19 |

| Emotional Eating (EE) 3rd tercile |

132 | 1.47 (1.04; 2.08), p < 0.05* |

111 | 0.96 (0.68; 1.34), p = 0.79 |

98 | 0.71 (0.50; 1.00), p < 0.05* |

| The p values below the statistical significance threshold are marked with the * p < 0.05. The regression was adjusted by BMI and age of the study participants., | ||||||

| High Adherence to DDP | Middle Adherence DDP | Low Adherence to DDP | ||||

| n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

|

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

86 | 1.32 (0.93; 1.85), p = 0.12 |

78 | 1.12 (0.79; 1.58), p = 0.52 |

62 | 0.67 (0.47; 0.96), p = 0.03* |

| Extraversion 1st tercile (Introversion) |

65 | 0.70 (0.50; 1.00), p < 0.05* |

80 | 1.18 (0.83; 1.66), p = 0.36 |

80 | 1.21 (0.86; 1.71), p = 0.28 |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

109 | 0.89 (0.64; 1.25), p = 0.50 |

111 | 1.06 (0.76; 1.49), p = 0.72 |

111 | 1.06 (0.75; 1.48), p = 0.75 |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

110 | 1.15 (0.82; 1.62), p = 0.41 |

99 | 0.96 (0.69; 1.35), p = 0.82 |

98 | 0.90 (0.64; 1.26), p = 0.54 |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

98 | 1.33 (0.94; 1.88), p = 0.10 |

80 | 0.84 (0.59; 1.18), p = 0.32 |

82 | 0.89 (0.63; 1.26), p = 0.51 |

| Emotional Stability 1st tercile (Neuroticism) |

80 | 0.78 (0.55; 1.09), p = 0.15 |

87 | 1.02 (0.73; 1.43), p = 0.92 |

93 | 1.26 (0.90; 1.78), p = 0.18 |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

102 | 1.10 (0.79; 1.53), p = 0.59 |

101 | 1.14 (0.81;1.59), p = 0.46 |

88 | 0.80 (0.57; 1.13), p = 0.20 |

| Uncontrolled Eating (UE) 3rd tercile |

107 | NS | 102 | 0.98 (0.70; 1.38), p = 0.91 |

104 | 1.02 (0.73; 1.43), p = 0.90 |

| Restrictive Eating (RE) 3rd tercile |

89 | 0.83 (0.59; 1.16), p = 0.28 |

90 | 0.95 (0.68; 1.33), p = 0.75 |

100 | 1.27 (0.91; 1.78), p = 0.16 |

| Emotional Eating (EE) 3rd tercile |

122 | 1.16 (0.83; 1.63), p = 0.39 |

112 | 1.02 (0.73; 1.43), p = 0.91 |

107 | 0.84 (0.60; 1.19), p = 0.33 |

| The p values below the statistical significance threshold are marked with the * p < 0.05. | ||||||

| High Adherence to UE | Middle Adherence to UE | Low Adherence to UE | ||||

| n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

n |

OR (CI95%), p |

|

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

83 | 1.21 (0.85; 1.71), p = 0.29 |

74 |

1.32 (0.92; 1.89), p = 0.13 |

69 | 0.65 (0.46; 0.92), p < 0.05* |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

120 | 1.22 (0.87; 1.71), p = 0.26 |

102 | 1.20 (0.85; 1.71), p = 0.30 |

109 | 0.70 (0.50; 0.98), p < 0.05* |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

125 | 1.74 (1.23; 2.45), p < 0.01* |

94 | 1.16 (0.82; 1.65), p = 0.40 |

88 | 0.51 (0.37; 0.72), p < 0.001* |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

99 | 1.36 (0.96; 1.91), p = 0.08 |

88 | 1.51 (1.06; 2.14), p < 0.05* |

73 | 0.51 (0.36; 0.72), p < 0.001* |

| Emotional Stability 1st tercile (Neuroticism) |

80 | 0.81 (0.57; 1.15), p = 0.23 |

63 | 0.66 (0.46; 0.95), p < 0.05* |

117 | 1.75 (1.25; 2.45), p < 0.01* |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

100 | 1.08 (0.77; 1.51), p = 0.66 |

80 | 0.87 (0.61; 1.23), p = 0.43 |

111 | 1.05 (0.76; 1.47), p = 0.76 |

| High Adherence to CR | Middle Adherence to CR | Low Adherence to CR | ||||

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

65 | 1.00 (0.74; 1.35), p = 0.99 |

73 | 0.83 (0.58; 1.17), p = 0.28 |

88 | 1.21 (0.86; 1.69), p = 0.28 |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

92 | 0.91 (0.64; 1.29), p = 0.59 |

118 | 1.06 (0.76; 1.48), p = 0.72 |

121 | 1.03 (0.74; 1.43), p = 0.88 |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

75 | 0.64 (0.45; 0.92), p < 0.05* |

106 | 0.97 (0.69; 1.35), p = 0.83 |

126 | 1.53 (1.09; 2.14), p < 0.05* |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

77 | 1.14 (0.80; 1.62), p = 0.48 |

95 | 1.12 (0.80; 1.57), p = 0.51 |

88 | 0.80 (0.57; 1.12), p = 0.19 |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

87 | 1.12 (0.79; 1.59), p = 0.53 |

95 | 0.82 (0.59; 1.14), p = 0.23 |

109 | 1.11 (0.80; 1.54), p = 0.54 |

| High Adherence to EE | Middle Adherence to EE | Low Adherence to EE | ||||

| Extraversion 3rd tercile |

91 | 1.76 (1.24; 2.49), p < 0.01* |

51 | 0.98 (0.66; 1.46), p = 0.93 |

84 | 0.61 (0.43; 0.85), p < 0.01* |

| Agreeableness 3rd tercile |

123 | 1.61 (1.13; 2.27), p < 0.01* |

82 | 1.28 (0.87; 1.88), p = 0.21 |

126 | 0.55 (0.40; 0.76), p < 0.001* |

| Conscientiousness 3rd tercile |

133 | 2.75 (1.92; 3.93), p <0.001* |

72 | 1.06 (0.72; 1.55), p = 0.76 |

102 | 0.39 (0.28; 0.55), p < 0.001* |

| Emotional Stability 3rd tercile |

104 | 1.90 (1.34; 2.69), p < 0.001* |

65 | 1.26 (0.86; 1.85), p = 0.24 |

91 | 0.47 (0.33; 0.66), p < 0.001* |

| Emotional Stability 1st tercile (Neuroticism) |

68 | 0.61 (0.42; 0.86), p < 0.01* |

54 | 0.83 (0.56; 1.22), p = 0.35 |

138 | 1.77 (1.28;2.47), p < 0.001* |

| Openness to Experiences 3rd tercile |

84 | 0.75 (0.54; 1.06), p = 0.11 |

70 | 1.17 (0.80; 1.71), p = 0.41 |

137 | 1.14 (0.83; 1.58), p = 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).