1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) constitutes a group of neurodevelopmental disorders with the core symptom of social dysfunction as well as limited and repetitive stereotyped behaviors. It directly affects its patients and indirectly affects their parents, experiencing the stigma attached to the disease. According to western study, parents of children with ASD are more likely to experience depression than those of children without ASD, with 34.2% of parents with of children with ASD presenting clinical depressive symptoms [

1]. Regarding Chinese research, the distribution rate ranges from 25 to 31% [

2,

3].

Parents of children with ASD usually experience distress, anxiety, depression, economic pressure, high divorce rate, and lower family well-being compared with those whose children have other developmental conditions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Differences have been noted in the depression distribution rate between fathers and mothers of children with ASD in that 50% of depressed mothers are compared with 17% of depressed mothers without children with ASD, whereas only 21% of depressed fathers of children with ASD, with 15% of fathers without [

8]. Mothers are most affected, with about one third of mothers experiencing from depression [

9]. When parents’ depression continue unrelieved, it may further aggravate the condition of children with ASD [

10].

Many factors are involved in developing depression among parents of children with ASD. One of those were social inhibition, a tendency, which characterizes the personality sensitivity (e.g., fear of negative evaluation), the social withdrawal (e.g., social interaction avoidance), and the behavioral inhibition (e.g., difficulty in communicating with others). Individuals with social inhibition may have difficulty regulating their emotions, which negatively impacts on mental and physical health [

11]. Research have shown that social inhibition is a risk factor for depression, on the other hand, depression can aggravate social avoidance problem as well[

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Even though social inhibition is viewed as trait, social inhibition behavior can occur among parents of autistic children[

12,

18,

19]. They may avoid taking their children to public places or participating in some social activities to reduce the social pressure caused by children’s abnormal behaviors. They may be sensitive to social information conveyed by others, perceived rejection and unfriendly treatment from others [

20,

21,

22].

Social support, on the other hand, is significantly associated with decreased depressive symptoms. Mothers with of children with ASD suffer blame and exclusion from other relatives, leading to a lack of social, family members’ support and loneliness [

23]. Researchers revealed that family support can be a protective factor against depressive symptoms [

24,

25,

26,

27], and limited social support is associated with the depression among parents of children with ASD[

6]. The relationship between social inhibition and perceived social support has been demonstrated[

14]. A study of patients with tumor showed that social inhibition influenced the perception of social support [

28].

Regarding the relationship among social Inhibition, family support, and depression, a study showed that perceived social support mediated the relationship between distressed personality (e.g., negative feelings and social inhibition) and depression [

29]. However, there is a lack of research on the intermediary role of family support in the relationship between social inhibition and depression among couples who are parents of children with ASD. Moreover, regarding relationships where partner effects influence outcome, no research has been carried out concerning the mediating role of family support between social inhibition and depression among the couple who are parents of children with ASD within a dyadic framework.

This study aims to explore how the social inhibition among parents of children with ASD affects their depressive symptoms process through family support, which can benefit further research on their depression treatment for them. When people live together, their individual behaviors will affect their own emotions as well as the emotions of others such as couples and siblings. Thus, studying the actor-partner effect among parents with children with ASD. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Mediation Model (APIMeM) makes it possible to estimate intermediary, indirect and direct effects, especially when dyad members are distinguishable (such as heterosexual couples), creating a understanding the unique contributions of the parents’ own social inhibition to their own (actor effect) and each other’s (partner effect) depressive symptoms while their own family support mediates the relationship[

30]. It was hypothesized that individual (actor) perceived family support would mediate the relationship between social inhibition and depressive symptoms for both wife and husband. In addition, it was hypothesized that the partner effect would be observed.

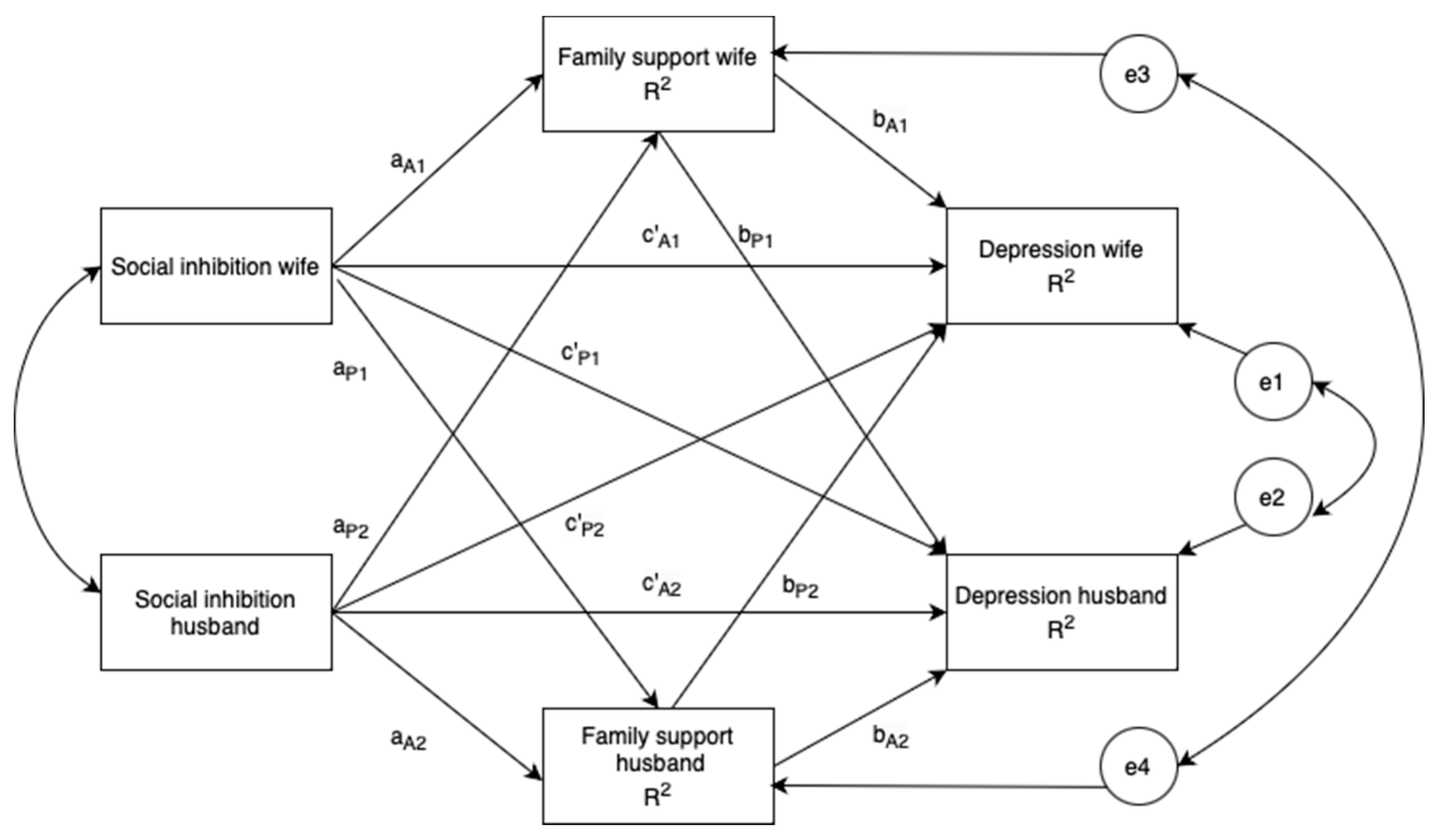

The hypotheses to be tested for each effect by APIMeM, such as actor-actor effect, actor-partner effect, partner-partner effect, and partner-actor effect, are presented below (Error! Reference source not found.).

Figure 1.

A hypothetical actor-partner interdependence mediation model in couples who are parents of ASD children. Note: a, direct effect of social inhibition on perceived family support; b, direct effect of perceived family support on depression; c′, direct effect of social inhibition on depression; A, actor effect; P, partner effect; C1, covariance between the two predictor variables; C2 & C3, covariance between the two error terms; E1, E2, E3 & E4, latent error terms; R2, coefficient of determination; 1, wife; 2, husband; Estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients; Significant path coefficients are in red. ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical actor-partner interdependence mediation model in couples who are parents of ASD children. Note: a, direct effect of social inhibition on perceived family support; b, direct effect of perceived family support on depression; c′, direct effect of social inhibition on depression; A, actor effect; P, partner effect; C1, covariance between the two predictor variables; C2 & C3, covariance between the two error terms; E1, E2, E3 & E4, latent error terms; R2, coefficient of determination; 1, wife; 2, husband; Estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients; Significant path coefficients are in red. ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

2. Materials and Methods

The study utilized a cross-sectional survey design with secondary data from Ms. Bijing He, which involved couples who were parents of children with ASD. The sample consisted of 397 pairs of parents, comprising 397 wives and 397 husbands, with ages ranging from 23 to 45 years old in mainland China. Ethics approval for this research was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Approval Number: PSY-2566-0324).

2.1. Participants

Participants were comprised of general Chinese parents with children diagnosed with ASD. The inclusion criteria included: (1) being spouses participating as a pair, (2) having one or more children with diagnosis of ASD, and (3) being able to read and write Chinese proficiently and independently complete the research questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included one spouse refusing to participate, and individuals unable to participate online. Upon completion of socio-demographic information, including age, sex, education level, and marital status, participants proceeded with the subsequent measurements described below.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Inventory for Interpersonal Problems (IIP)- social inhibition subscale.

IIP is a self-report questionnaire which measures interpersonal difficulties across eight subscales, those derived from the following dimensions: affiliation (from hostile/cold to friendly behavior), domineering (from submissive to controlling behavior). In this study only socially inhibited subscale was used (for example, “I am too afraid of other people”)[

31]. A higher score indicates a higher level of social inhibition. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.84. in Chinese version[

32]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

2.2.2. Multidimensional Scale for Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)- family support subscale

The MSPSS is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess the extent to which an individual perceives support from family members. It comprises 4 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale [

33]. Higher scores indicate a greater perceived level of support. The Chinese version of the MSPSS has been validated and shown to be reliable [

34]. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was calculated to be 0.86.

2.2.3. Core Symptom Index (CSI)- Depression subscale.

CSI-Depression is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess the extent to which an individual perceives depression. It consisted of 5-item, 5-point Likert type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (always)[

35]. The higher score indicates the higher level of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for depression subscale was 0.85. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was calculated to be 0.87.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was applied with demographic data, social inhibition, family support and depression scores. Covariates were analyzed using number and percentage. Pearson’s correlation was used for testing the correlation and direction of correlation among the variables. Descriptive and Pearson correlation analysis were conducted using IBM SPSS Version 26.0. Next, we applied the Actor-Partner Interdependence Mediation Model (APIMeM) by Amos 26.0 to investigate the mediating effects of the wife and husband’s perceived family support on the relation between depression and social inhibition. This model aimed to investigate the impact of social inhibition (independent variable) on depression (dependent variable) mediated by perceived support from family (mediator).

Within the Actor-Partner Interdependence mediation Model, social inhibition’s effect on perceived family support is denoted as a perceived family support’s effect on depression as b, and social inhibition’s direct effect on depression as c’. Subsequently, the total effect (TE) (ab+c’), the mediating effects (ab), and the direct effects (a, b and c’) and were computed (Error! Reference source not found.). The mediating effect was estimated as the multiplication of the direct effects a and b, indicating the portion of the relation between social inhibition and depression interpreted by perceived support from family members. Meanwhile, the TE was calculated (c’+ab), representing the association on social inhibition and depression before adjusting for family support from family members.

The APIM analysis was conducted using structural equation modeling in AMOS 22 and IBM SPSS version 26 with a dyadic dataset. To test the P value of the total and mediating effects, a 95% confidence interval corrected for bias through Monte Carlo sampling was used to bootstrap sample 5000. The overall fitness of the APIMeM model is evaluated by the model fit index, includings CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. All statistical analyses are two-tailed, and the P value is less than 0.05.

Table 1.

Calculation for the total effect (TE), direct effect, and indirect effects (IE) in the actor–partner interdependence mediation model.

Table 1.

Calculation for the total effect (TE), direct effect, and indirect effects (IE) in the actor–partner interdependence mediation model.

|

Actor Effect (Individual’s social inhibition à individual’s depression) |

| Wife |

Total effect |

aA1*bA1 + aP1*bP2 + c’A1 |

Wife actor TE |

| |

Indirect effect |

aA1*bA1 + aP1*bP2 |

Wife actor total IE |

| |

Actor-actor simple IE |

aA1*bA1 |

Wife actor-actor IE |

| |

Partner-partner simple IE |

aP1*bP2 |

Wife partner-partner IE |

| |

Direct effect |

c’A1 |

Wife actor direct effect |

| Husband |

Total effect |

aA2*bA2 + aP2*bP1 + c’A2 |

Husband actor TE |

| |

Total IE |

aA2*bA2 + aP2*bP1 |

Husband actor total IE |

| |

Actor-actor simple IE |

aA2*bA2 |

Husband actor-actor IE |

| |

Partner-partner simple IE |

aP2*bP1 |

Husband partner-partner IE |

| |

Direct effect |

c’A2 |

Husband actor direct effect |

|

Partner Effect (Individual’s social inhibition à partner’s depression) |

| Wife |

Total effect |

aA1*bP1 +aP1*bA2 + c’P2 |

Wife partner TE |

| |

Total IE |

aA1*bP1 +aP1*bA2 |

Wife partner total IE |

| |

Actor-actor simple IE |

aA1*bP1 |

Wife actor-partner IE |

| |

Partner-actor simple IE |

aP1*bA2 |

Wife Partner-actor IE |

| |

Direct effect |

c’P2 |

Wife partner direct effect |

| Husband |

Total effect |

aA2*bP2 + aP2*bA1 + c’P1 |

Husband partner TE |

| |

Indirect effect |

aA2*bP2 + aP2*bA1 |

Husband partner total IE |

| |

Actor-partner simple IE |

aA2*bP2 |

Husband actor-partner IE |

| |

Partner-actor simple IE |

aP2*bA1 |

Husband Partner-actor IE |

| |

Direct effect |

c’P1 |

Husband partner direct effect |

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Results

Totally, 794 participants were included in the data analysis, consisting of 397 wives (W) and 397 husbands (H). While wives’ ages ranging from 26 to 43 years old, husbands’ ages varied from 23 to 45 years old. Overall, wives tended to be younger than husbands (p < 0.001). The greatest proportion earned university degrees (47.3%), were employed (94.1%), resided in urban areas (68.3%), and reported a household monthly income exceeding 5000 CNY (99.2%). Additionally, most families incurred an annual cost of approximately 30,000 CNY for the care of the child with ASD (81.6%) and dedicated at least 6 hours daily to parenting duties (72.7%), with wives typically spending more time in parenting (p < 0.001). Regarding marital duration, a significant portion of participants reported being married for over ten years. Further details can be found in

Table 2.

Table 3 displays the psychosocial variables. There were no significant differences in mean scores between wives and husbands, except for depressive symptoms, where wives scored significantly higher than husbands (p = 0.001).

3.2. Correlation Results

The findings revealed a significant positive correlation between both wives’ and husbands’ levels of social inhibition and their respective depressive symptoms (r = 0.338 to 0.405, p < 0.01). In contrast, there existed a negative correlation between the perception of family support and their social inhibition (r = -0.154, p < 0.01), as well as between their own or their partner’s depressive symptoms (r = -0.077 to -0.311, p < 0.05). Notably, the positive association between husbands’ social inhibition and their partners’ depressive symptoms (r = 0.71, p < 0.05), along with wives’ depression being positively correlated with their husbands’ depression (r = 0.257, p < 0.01) (

Table 4).

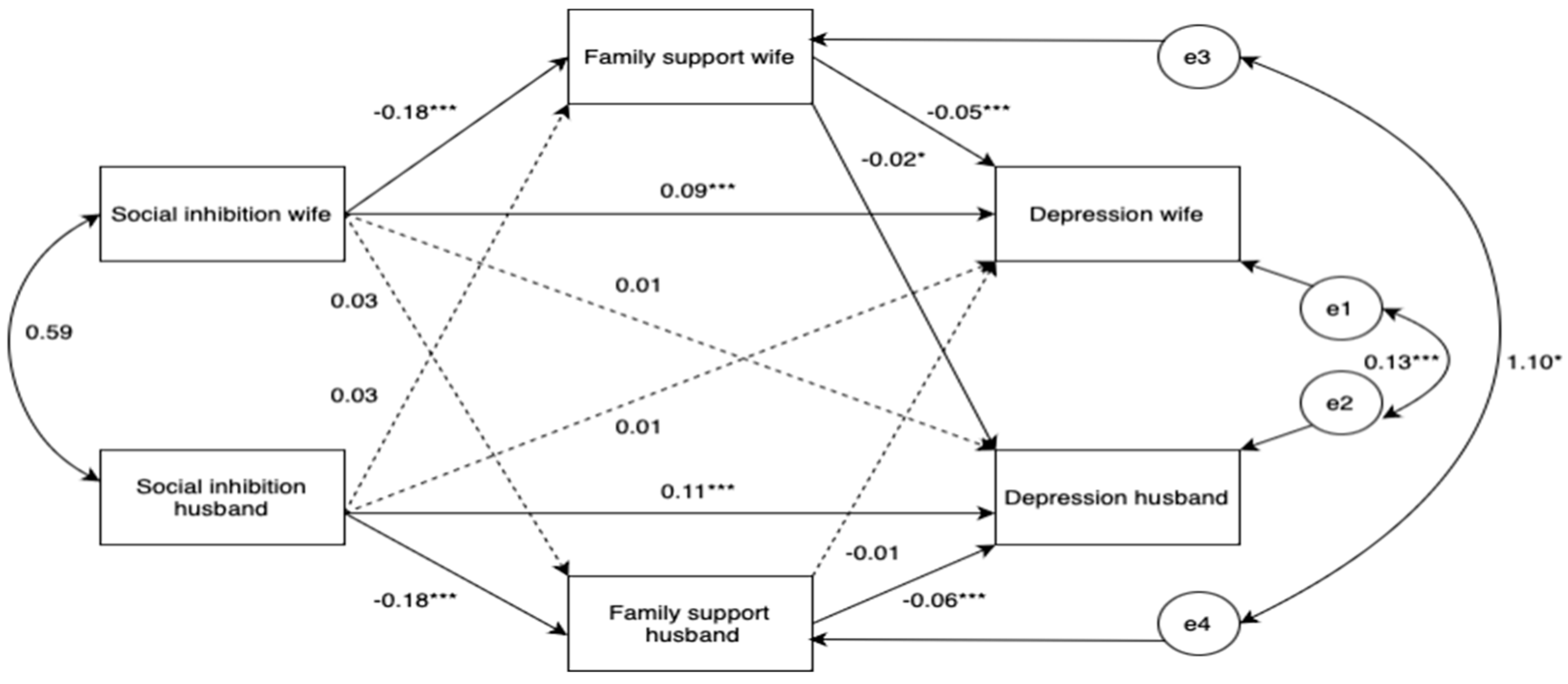

3.3. APIMeM analysis results (Standardized Estimates)

Overall, our analysis revealed actor effects for both wives and husbands, indicating direct or indirect impacts on their own depressive symptoms, while partner effects were not evident. Specifically, both wife’s and husband’s depression were predicted by their own levels of social inhibition (β = 0.290-0.362, p ≤ 0.001) and perceived family support (β = -0.225 to -0.212, p < 0.001). Additionally, their own social inhibition was associated with their perceived family support (β = -0.154-0.153, p < 0.001). Interestingly, husbands’ depression was significantly influenced by their wives’ perceived family support (β = -0.071, p = 0.031). However, husbands’ social inhibition (β = 0.041, p = 0.235) and perceived family support (β = 0.042, p = 0.197) were not significantly associated with wives’ depression.

Moreover, significant correlations were observed between wives’ and husbands’ perceptions of family support (β = 0.09, p = 0.15), as well as between wives’ and husbands’ levels of social inhibition (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). The R-squared values for the entire model were 0.060 for wives’ perceived family support and 0.061 for husbands’ perceived family support. Regarding IEs, both wives’ and husbands’ social inhibition were associated with their own depression through their perceived family support (β = 0.010, p < 0.001). Additionally, wives’ social inhibition could influence husbands’ depression through wives’ perceived family support (β = 0.003, p = 0.018). However, the social inhibition of either wives or husbands did not exhibit a significant TE on their partner’s depression (β = 0.012, p = 0.248-0.259). Moreover, wives’ and husbands’ depression were not influenced by their own or their partner’s social inhibition through their partner’s perceived family support. Essentially, no partnerpartner or partner-actor effects were observed for either wives or husbands (β = -0.002-0.000, p = 0.317-0.514). (See

Table 5 and

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate how the social inhibition of couples might impact either their own or their partner’s experience of depressive symptoms, with ’perceived family support’ serving as a mediating factor among parents with children receiving a diagnosis of ASD within the dyadic framework. To the best of our knowledge, the current study was the first to examine the effects of social inhibition on depressive symptoms through perceived family support among their ASD parents. The findings of the current study improve our understanding of how social inhibition contributes to perceived family support and how perceived family support is associated with the depression of wife and husband when parenting their children with ASD in Chinese couples. The results revealed that parents’ social inhibition was both directly and indirectly correlated with their own depression. It suggests that Chinese family with children with ASD may benefit from reduced social inhibition and family support targeting intervention.

Consistent with related studies, the positive correlation between social inhibition and depression showed on the parents of children with ASD in our study. Perceived family support is both negatively correlated with social inhibition and depression.

In dyadic analysis using the APIMeM, it confirms our hypothesis that high levels of social inhibition would be associated with lower levels of perceived family support, and lower perceived family support was positively associated with depression for both wives and husbands who were the parents of children with ASD. These findings were supported by some related studies that social inhibition was associated with depression among mothers of children with ASD [

36], and perceived family support was a common mediator on depression [

37]. Raising children with ASD may limit parents’ interpersonal relationships and social life due to the stigma, which may make these parents more withdrawn and anxious about interpersonal communication and efficiently contribute to social inhibition [

38]. Parenting children with ASD itself takes these parents a great deal of time, so they will be less involved in educational research, community activities and public affairs [

9]. As we know, social inhibition may affect individuals’ poor perception of family support [

39]. These parents may perceive lower family support due to their improving social inhibition, leading to depression to some extent.

However, the partner effect was not as significant as the actor effect, which was against our hypothesis based on the family system theory that family member’s emotions and behaviors may affect his/her partner [

40]. This nonsignificant dyadic level was supported by a related study on emotional stress and dysregulation among parents of individuals with ASD in China[

41].

Even though there was a significant indirect effect of wives on their husbands’ depressive symptoms through the wives’ perceived social support, the total effect of this partner effect was still not significant. In other words, a partner’s perceived family support does not appear to affect an individual’s depression.

The fact that one partner’s social inhibition and perceived family support may not contribute to the other partner’s depression could be related to the fact wives and husbands have distinct roles in daily family based on the traditional Chinese culture or most of the cultures around the world. By that wives are expected to be main caregivers for family members, and for disabled persons in the family[

42,

43,

44]. While wives have such burden in caring family members, husbands are expected to provide financial support and some assistance in childcare[

45]. It is important to note that in the present study, wives exhibited higher levels of depression and lower levels of perceived family support. Although one may have felt supported by family, the impact that could have occurred on the partner was not shown. The reason may be because it was unclear from whom such support originated. Support from other family members, such as grandparents, may not have a significant effect on an individual’s depression compared to spousal support[

46,

47]. It is plausible that, in this case, the level of spousal support among families with children with ASD was low.

Although a small indirect effect was observed, with wives’ social inhibition having a potential impact on husbands’ depression through wives’ perceived family support, this effect was not statistically significant. It is proposed that wives’ perception of inadequate family support could lead to their withdrawal, thereby contributing to their husbands’ unhappiness. Conversely, no such pathway was observed from husbands to wives, indicating distinct gender roles within Chinese families. Nonetheless, the absence of a partner effect may be associated with individuals’ social inhibition, particularly considering that Chinese mothers and fathers typically exhibit introverted and implicit emotional interactions [

48], In addition, a study has shown that parents with ASD children show to have hypersensitivity to criticism, anxiety and aloofness [

49], these traits may be exacerbated in stressful families with ASD.

Clinical implications

Support from both one’s partner and other family members is crucial for parents raising children with ASD. Ensuring that married couples are able to offer and receive adequate family support is vital in preventing or alleviating depressive symptoms. Skills for both providing and receiving support can be taught and learned, especially for individuals with social inhibitions, therefore, strategic intervention programs can be implemented to foster effective family support networks. Factors associated with social inhibition should be screened among couples with children with ASD. When screening couples for social inhibition, it’s essential to consider a range of factors that may influence this trait. This includes not only personality traits but also the presence of ASD spectrum disorder within either partner. Individuals on the autism spectrum may face additional challenges in social interactions, which can affect their ability to provide support to their spouse and receive support in return. Understanding these dynamics is key to providing tailored support and interventions for couples dealing with the complexities of ASD parenting.

Moreover, addressing social inhibition among couples with ASD children requires a multifaceted approach. This may involve not only identifying and addressing individual personality traits and mental health challenges but also providing resources and support to enhance communication and coping strategies within the relationship. By addressing these factors comprehensively, couples can better navigate the unique stressors associated with raising a child with ASD and strengthen their relationship in the process.

Limitation

Firstly, the reliance on self-reported measures introduces the possibility of biases, such as social desirability and response bias, which may impact the accuracy of the findings. Secondly, important covariates such as parental stress were not included in the analysis, potentially confounding the relationship between the variables under investigation. Thirdly, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to establish causal relationships or determine the directionality of associations among the examined variables. Future research employing longitudinal designs is recommended to elucidate the temporal dynamics of these parenting constructs and their impact on depressive symptoms over time.

Additionally, the generalizability of the findings may be limited by the study’s focus on married parents residing in mainland China. Other family structures and cultural contexts may yield different patterns of association between family support, social inhibition, and depressive symptoms. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extending these findings to diverse cultural and social contexts, including Chinese populations outside mainland China and individuals from Western cultures.

Lastly, the exclusion of spousal support as a variable of interest in this study represents a notable limitation. Given its potential relevance to partner’s depression, future research should explore the role of spousal support in mitigating depressive symptoms within the context of parenting children with ASD.

5. Conclusions

The study’s findings suggest the presence of actor effects but not partner effects in the relationships among couples’ social inhibition, perceived social support, and depressive symptoms. This study makes several contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it is one of the first studies to explore the mechanisms underlying the associations between social inhibition and depressive symptoms, incorporating both partners’ perceptions of social support as mediators. Secondly, by employing dyadic analysis, it allows for an investigation into potential family processes influencing these relationships. Thirdly, our results highlight the importance of providing couples with skills to effectively offer and receive family support in mitigating social inhibition. Additionally, interventions targeting fathers should emphasize their active involvement in parenting and collaboration with their partners in caring for children with ASD, potentially leading to improved outcomes for both parents and children in ASD-affected families. The study also acknowledges its limitations and offers suggestions for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, T.P., T.W., N.W., B.H., and D.W.; software, T.P., T.W. and N.W.; validation, T.P., T.W. and N.W.; formal analysis, T.P., T.W. and N.W.; investigation, T.P., T.W. and N.W.; resources, T.P., T.W., N.W. and B.H.; data curation, T.P., T.W. and N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P., T.W., N.W., B.H. and D.W.; writing—review and editing, T.P., T.W., N.W., B.H. and D.W.; visualization, T.P. and T.W.; supervision, T.W.; project administration, T.W.; funding acquisition, T.P., T.W. and N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (protocol code: PSY-2566-0324 and date of ethics exemption approval: 25 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the risk of identifying individual is extremely low in this secondary analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses her sincere gratitude to Chiang Mai university for offering 2 years CMU Presidential Scholarship from 2022 to 2024. We also thank Ms. Bijing He for providing us with the data and the parents of ASD who once participated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cohrs, A.C.; Leslie, D.L. Depression in Parents of Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Claims-Based Analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2017, 47, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Leung, D.C.K. Linking child autism to parental depression and anxiety: The mediating roles of enacted and felt stigma. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2021, 51, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, D.; Pan, S.; Zhai, J.; Xia, W.; Sun, C.; Zou, M. The relationship between 2019-nCoV and psychological distress among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Globalization and health 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, J.S.; Van Hecke, A.V. Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: a review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical child and family psychology review 2012, 15, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; You, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Du, X.; Wang, Y. Effects of a Web-Based Parent-Child Physical Activity Program on Mental Health in Parents of Children with ASD. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitsika, V.; Sharpley, C.F.J.J.o.P.; Schools, C.i. Stress, anxiety and depression among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. 2004, 14, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanxing, O.; Caihui, C.; Linghua, C. A Study on Mental Health Status of Parents of Autistic Children. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 2010, 12, 947–949. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, M.B.; Hwang, C.J.J.o.i.d.r. Depression in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. 2001, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, L. A Study on Life Adaptation and Social Participation of Parents of Children with Autism. Master’s thesis of Institute of Youth and Child Welfare, Cultural University.

- Suhua, Z.; Yueying, C.; Minying, Z.; Xiaoli, Y. Effects of narrative psychotherapy on quality of life and mental health of parents of children with autism. Chinese Tropical Medicine 2015, 15, 962–965. [Google Scholar]

- Duijndam, S.; Karreman, A.; Denollet, J.; Kupper, N. Emotion regulation in social interaction: Physiological and emotional responses associated with social inhibition. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology 2020, 158, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; van Reekum, R. Social inhibition as a mediator of neuroticism and depression in the elderly. BMC Geriatr 2012, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Brodaty, H.; Boyce, P.; Mitchell, P.; Wilhelm, K.; Hickie, I.; Eyers, K. Psychomotor disturbance in depression: defining the constructs. Journal of affective disorders 1993, 27, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.G.; Parker, G.B.; Malhi, G.S.; Mitchell, P.B.; Wilhelm, K.; Proudfoot, J.J.P.; Health, M. Social inhibition and treatment-resistant depression. 2007, 1, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, L.E.; Bieling, P.J.J.J.o.R.i.P. Interpersonal convergence of personality constructs in dynamic and cognitive models of depression. 1996, 30, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K.A.; Watkins, E.R.; Mullan, E.G.J.B.r. ; therapy. Submissive interpersonal style mediates the effect of brooding on future depressive symptoms. 2010, 48, 966–973. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Van Reekum, R.J.B.g. Social inhibition as a mediator of neuroticism and depression in the elderly. 2012; 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pattini, E.; Carnevali, L.; Troisi, A.; Matrella, G.; Rollo, D.; Fornari, M.; Sgoifo, A.J.S.; Health, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Psychological characteristics and physiological reactivity to acute stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. 2019, 35, 421–431.

- Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.L. , Thirajet. Personality traits influencing somatization symptoms and social inhibition in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2014, 9, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wenjun, G.; Mengjuan, H.; Cheng, L. The effect of parental discrimination perception on intergroup relationship in children with autism: A moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education S 2021, 37, 854–863. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers, E.; Duijndam, S.; Schiffer, A.S.; Scherders, M.J.; Habibović, M.; Denollet, J. Validity of the 15-item social inhibition questionnaire in outpatients receiving psychological or psychiatric treatment: The association between social inhibition and affective symptoms. General hospital psychiatry 2021, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.E.; Burbine, T.; Bowers, C.A.; Tantleff-Dunn, S.J.C.m.h.j. Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. 2001; 37, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Manor-Binyamini, I.; Shoshana, A. Listening to Bedouin Mothers of Children with Autism. Culture, medicine and psychiatry 2018, 42, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levens, S.M.; Elrahal, F.; Sagui, S.J.J.J.o.S.; Psychology, C. The role of family support and perceived stress reactivity in predicting depression in college freshman. 2016; 35, 342. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.H.; Greenberg, J.S.; Seltzer, M.M. Parenting a Child with a Disability: The Role of Social Support for African American Parents. Families in society : the journal of contemporary human services 2011, 92, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.E.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Miranda, R., Jr.; Rizzo, C.J.; Justus, A.N.; Clum, G. Gender, social support, and depression in criminal justice-involved adolescents. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology 2011, 55, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, K.Q.P.; Loh, P.R. Mental Health and Coping in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Singapore: An Examination of Gender Role in Caring. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2019, 49, 2129–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheepers, E.R.M.; de Rooij, B.H.; Pijnenborg, J.M.A.; van Huis-Tanja, L.H.; Ezendam, N.P.M.; Hamaker, M.E. Perceived social support in patients with endometrial or ovarian cancer: A secondary analysis from the ROGY care study. Gynecologic oncology 2021, 160, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalsoom, U.; Hanifa, B. Depression, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, and perceived social support in type D and non-type D individuals. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology 2021, 27, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, T.; Macho, S.; Kenny, D.A.J.S.E.M.A.M.J. Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor-partner interdependence model. 2011; 18, 595–612. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, L.M.; Rosenberg, S.E.; Baer, B.A.; Ureño, G.; Villaseñor, V.S. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1988, 56, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.-w.; Jiang, G.-r.; Zhang, Q.-j. A report on the application of Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32) to 1498 college students. Chin J of Clin Psychol 2010, 18, 466–468. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K.J.J.o.p.a. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. 1988; 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.S.M.; Liu, T.W.; Ho, L.Y.W.; Chan, N.H.; Wong, T.W.L.; Tsoh, J. Assessing the level of perceived social support among community-dwelling stroke survivors using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Lertkachatarn, S.; Sirirak, T.; Kuntawong, P.J.I.P. Core Symptom Index (CSI): Testing for bifactor model and differential item functioning. 2019, 31, 1769–1779.

- Pattini, E.; Carnevali, L.; Troisi, A.; Matrella, G.; Rollo, D.; Fornari, M.; Sgoifo, A. Psychological characteristics and physiological reactivity to acute stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Stress and Health 2019, 35, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, Z. Language representation of the level of depression : the mediating role of negative cognitive processing bias and perceived social support. Guangzhou University, 2020.

- W, R. Research on the relationship between the mental health status of mothers of children with autism and its relationship with emotional resilience and social support. Advances in Psychology 2023, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levens, S.M.; Elrahal, F.; Sagui, S.J. The role of family support and perceived stress reactivity in predicting depression in college freshman. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2016, 35, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Families as systems. Annual review of psychology 1997, 48, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Han, Z.R.; Bai, L.; Gao, M.M. The mediating role of parenting stress in the relations between parental emotion regulation and parenting behaviors in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorders: A dyadic analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2019, 49, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Han, Z.R. Parental stress, involvement, and family quality of life in mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorder in mainland China: A dyadic analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2020, 107, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, Y.; Riccadonna, S.; Venuti, P. Parenting dimensions in mothers and fathers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2014, 8, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.Q.P.; Loh, P.R. Mental health and coping in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Singapore: An examination of gender role in caring. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2019, 49, 2129–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.A.; York, K.; Rothenberg, A.; Bissell, L.J. Parenting a child with Asperger’s syndrome: a balancing act. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2015, 24, 2310–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekas, N.V.; Timmons, L.; Pruitt, M.; Ghilain, C.; Alessandri, M. The Power of Positivity: Predictors of Relationship Satisfaction for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2015, 45, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. The Roles of Family and School Members in Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours in China: A Narrative Review. Children (Basel) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.L.C.; Lai, K.Y.C. Paternal and Maternal Experiences in Caring for Chinese Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Hong Kong. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 2016, 10, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, N.; Shaked, M. Psychiatric disorders in parents of children with autism: a meta-analysis. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2005, 46, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).