Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Dynamics of the Energy Transition in the MENA Region

2.2. Critical Review of Traditional Analytical Methods

2.3. Neo-Institutional Theory: Broadening the Analytical Lens

2.4. Governance Structures, Informal Institutions and Energy Transition

3. Methodology

3.1. Neo-Institutional Analytical Framework for Energy Transition

3.2. Data Collection Methods and Analytical Procedures

4. New Institutional Analysis of Energy Transition in the MENA Region

4.1. Institutional Influences on Energy Policies and Practices

4.2. Applying the New Institutional Framework to Country-Specific Contexts

4.3. Institutional Barriers to Energy Transition in the MENA Region

5. Strategic Recommendations and Vision for a Just and Sustainable Energy Transition

5.1. Leveraging Lessons for Institutional Reform

5.2. Strengthening Governance and Policy Frameworks

5.3. Strengthening Market Dynamics and Infrastructure

5.4. Fostering Regional Cooperation and Knowledge Sharing

5.5. Integrating Equity and Sustainability in the Energy Transition

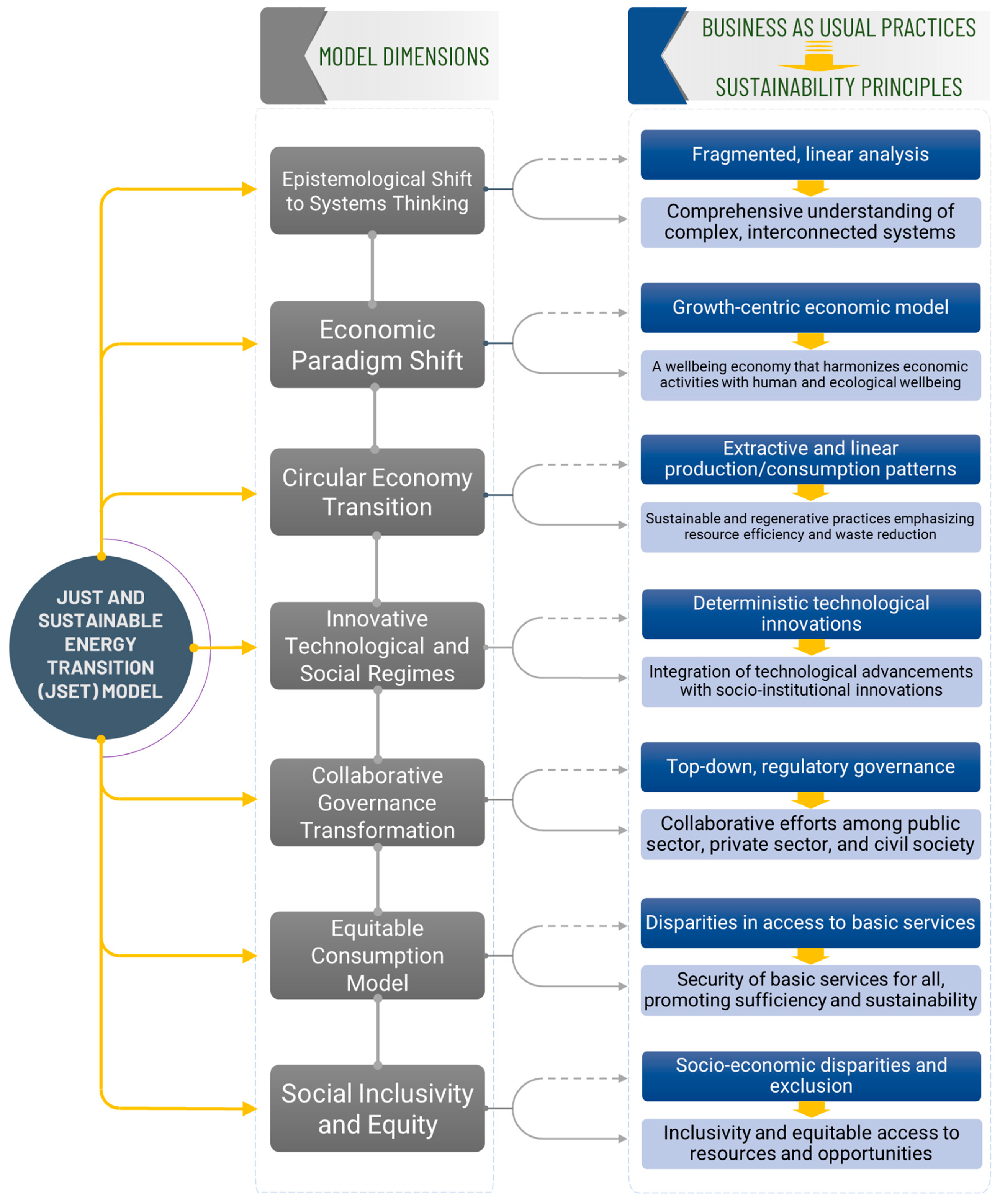

5.6. The Just and Sustainable Energy Transition (JSET) Model

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews-Speed, P. Applying institutional theory to the low-carbon energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S., Beveridge, R., & Röhring, A. (2016). Energy Transitions and Institutional Change: Between Structure and Agency. Conceptualizing Germany’s Energy Transition, 21–41. [CrossRef]

- Chaikumbung, M. Institutions and consumer preferences for renewable energy: A meta-regression analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D.; Dumitru, M.; Perevoznic, F.M. Carbon reduction and energy transition targets of the largest European companies: An empirical study based on institutional theory. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 4, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanelli, J.M.M.; Sang, E.V.; de Oliveira, C.E.; Campos, F.d.R.; Lazaro, L.L.B.; Edomah, N.; Igari, A.T. An institutional framework for energy transitions: Lessons from the Nigerian electricity industry history. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 97, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R. (2020). A Fine Balance: The Geopolitics of the Global Energy Transition in MENA. Lecture Notes in Energy, 115–150.

- Terrapon-Pfaff, J., Prantner, M., & Ersoy, S. R. (2022). Risikobewertung und Risikokostenanalyse der MENA-Region. MENA-Fuels: Teilbericht, 8.

- Albaker, A.; Abbasi, K.R.; Haddad, A.M.; Radulescu, M.; Manescu, C.; Bondac, G.T. Analyzing the Impact of Renewable Energy and Green Innovation on Carbon Emissions in the MENA Region. Energies 2023, 16, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikalakis, A.; Tomtsi, T.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Poullikkas, A.; Malamatenios, C.; Giakoumelos, E.; Jaouad, O.C.; Chenak, A.; Fayek, A.; Matar, T.; et al. Review of best practices of solar electricity resources applications in selected Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2838–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, A. M., & Anderies, J. M. (2013). Institutional Factors That Determine Energy Transitions: A Comparative Case Study Approach. Renewable Energy Governance, 33–61.

- Kucharski, J.B.; Unesaki, H. An institutional analysis of the Japanese energy transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2018, 29, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforidis, T.; Katrakilidis, C.; Karakotsios, A.; Dimitriadis, D. The dynamic links between nuclear energy and sustainable economic growth. Do institutions matter? Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 139, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, P., & Uddin, N. (2021). Governance Amid the Transition to Renewable Energy in the Middle East and North Africa. Low Carbon Energy in the Middle East and North Africa, 237–262. [CrossRef]

- Correljé, A.; Pesch, U.; Cuppen, E. Understanding Value Change in the Energy Transition: Exploring the Perspective of Original Institutional Economics. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2022, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Khan, S.U.; Ali, M.A.S.; Safi, A.; Gao, Y.; Luo, J. Role of institutional quality and renewable energy consumption in achieving carbon neutrality: Case study of G-7 economies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 814, 152797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Sultana, N. Impacts of institutional quality, economic growth, and exports on renewable energy: Emerging countries perspective. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Patel, G.; Hu, G. Effects of institutional quality and political risk on the renewable energy consumption in the OECD countries. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alariqi, M.; Long, W.; Singh, P.R.; Al-Barakani, A.; Muazu, A. Modelling dynamic links among energy transition, technological level and economic development from the perspective of economic globalisation: Evidence from MENA economies. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3920–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, E., Alston, L., & Mueller, B. (2023). New Institutional Economics and Cliometrics. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Dahmani, M. Environmental quality and sustainability: exploring the role of environmental taxes, environment-related technologies, and R&D expenditure. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2023, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.; Horvey, S.S. Institutional quality and renewable energy capital flows in Africa. Futur. Bus. J. 2023, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Rodríguez, Y.; Niño-Villamizar, Y.A. Effective team management in energy transition projects: a perspective on critical success factors. Case of the mining-energy sector in Colombia. DYNA 2023, 90, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, H.; Chtourou, N. Do Institutional Quality, Financial Development, and Economic Growth Improve Renewable Energy Transition? Some Evidence from Tunisia. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 14, 2927–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouaiana, A. (2022). Rural Energy Communities as Pillar towards Low Carbon Future in Egypt: Beyond COP27. Land, Ben Youssef, A., & Dahmani, M. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Digitalization, Tax Revenues, and Energy Resource Capacity on Environmental Quality: Fresh Evidence from CS-ARDL in the EKC Framework. Sustainability, 16(2), 474.11(12), 2237. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023). World Energy Outlook 2023. International Energy Agency.

- IRENA. (2022). World Energy Transitions Outlook 2022. International Renewable Energy Agency.

- World Bank. (2023). World development indicators. Retrieved from https://databank.worldbank.

- Dahmani, M.; Mabrouki, M.; Ben Youssef, A. The ICT, financial development, energy consumption and economic growth nexus in MENA countries: dynamic panel CS-ARDL evidence. Appl. Econ. 2022, 55, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmani, M.; Mabrouki, M.; Ragni, L. Decoupling Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Economic Growth: A Case Study of Tunisia. Energies 2021, 14, 7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzymowski, A. Energy Transformation and the UAE Green Economy: Trade Exchange and Relations with Three Seas Initiative Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, M.B.; Moore, S.; Adornetto, T. Suspending democratic (dis)belief: Nonliberal energy polities of solar power in Morocco and Tanzania. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 96, 102942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanouar, Z.; Essid, L. Extending the resource curse hypothesis to sustainability: Unveiling the environmental impacts of Natural resources rents and subsidies in Fossil Fuel-rich MENA Countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 87, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A.C. (1920). The Economics of Welfare. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Coase, R.H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. Classic Papers in Natural Resource Economics, 87–137.

- Stern, N.H. (2007). The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

- Rosenberg, N. (1982). Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- North, D.C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. E., & Farley, J. (2004). Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. Island Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2010). Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up. The New Press.

- Williamson, O.E. (1996). The Mechanisms of Governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147. [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W. (1996). On the nature of institutional embeddedness: labels vs explanation. Advances in strategic management, 13, 293-300.

- Oliver, C. (1997). Sustainable competitive advantage: combining institutional and resource-based views. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9), 697–713. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Approaching adulthood: the maturing of institutional theory. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becheikh, N. Political stability and economic growth in developing economies: lessons from Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt ten years after the Arab Spring. Insights Into Reg. Dev. 2021, 3, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpanachi, E.; Ambe-Uva, T.; Fassih, A. Energy regime reconfiguration and just transitions in the Global South: Lessons for West Africa from Morocco’s comparative experience. Futures 2022, 139, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminova, M.; Jegers, M. Informal Structures and Governance Processes in Transition Economies: The Case of Uzbekistan. Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, R., & Rignall, K. (2019). Kingdom of the Sun: a critical, multiscalar analysis of Morocco’s solar energy strategy. Energy Research & Social Science, 51, 20–31. [CrossRef]

- Omri, E.; Chtourou, N.; Bazin, D. Technological, economic, institutional, and psychosocial aspects of the transition to renewable energies: A critical literature review of a multidimensional process. Renew. Energy Focus 2022, 43, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Looze, A., & Cuppen, E. (2023). To wind up changed: Assessing the value of social conflict on onshore wind energy in transforming institutions in the Netherlands. Energy Research & Social Science, 102, 103195. [CrossRef]

- Shayan, F.; Harsij, H.; Badulescu, D. Regional institutions’ contribution to energy market integration in the middle East. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 51, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, Y.M.; Sunikka-Blank, M. Governing renewable energy transition in conflict contexts: investigating the institutional context in Palestine. Energy Transitions 2020, 4, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M.; Elagib, N.A. Towards understanding the integrative approach of the water, energy and food nexus. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 574, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakid, W.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. The Influence of Green Entrepreneurship on Sustainable Development in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Formal Institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Colantonio, E. The institutional and socio-technical determinants of renewable energy production in the EU: implications for policy. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2022, 49, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Cifuentes-Faura, J., Talbi, B., Sadiq, M., Si Mohammed, K., & Bashir, M. F. (2023). Dynamic correlated effects of electricity prices, biomass energy, and technological innovation in Tunisia’s energy transition. Utilities Policy, 82, 101521. [CrossRef]

- Purkus, A., Gawel, E., & Thrän, D. (2012). Bioenergy governance between market and government failures: A new institutional economics perspective. UFZ Discussion Paper, No. 13/2012, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Leipzig.

- Nie, Y.; Zhang, G.; Duan, H.; Su, B.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Gao, X. Trends in energy policy coordination research on supporting low-carbon energy development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, L.; Brown, C.; Foster, J.; Wagner, L.D. Australian Renewable Energy Policy: Barriers and Challenges. Renew. Energy 2013, 60, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Sharif, A.; Ozturk, I.; Afshan, S. Dynamic and threshold effects of energy transition and environmental governance on green growth in COP26 framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 179, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarihi, A.; Cherni, J.A. Political economy of renewable energy transition in rentier states: The case of Oman. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 33, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himri, Y.; Rehman, S.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Himri, S.; Mellit, A.; Merzouk, M.; Merzouk, N.K. Overview of the Role of Energy Resources in Algeria’s Energy Transition. Energies 2022, 15, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraiou, A.; Necaibia, A.; Boutasseta, N.; Mekhilef, S.; Dabou, R.; Ziane, A.; Sahouane, N.; Attoui, I.; Mostefaoui, M.; Touaba, O. Status of renewable energy potential and utilization in Algeria. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 246, 119011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallah, S.; Boudaoud, S.; Matallah, A.; Ferhaoui, M. The role of fossil fuel subsidies in preventing a jump-start on the transition to renewable energy: Empirical evidence from Algeria. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhraoui, K.; Awopone, A.K.; von Hirschhausen, C.; Kebir, N.; Agadi, R. Toward a systemic approach to energy transformation in Algeria. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2023, 8, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamirouche, H.; Megherbi, A.; Djedaa, N.E.I.; Bouferkas, R. Energy security index of Algeria: an integrated approach. les Cah. du cread 2022, 38, 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjer, H., Chaouche, S., Michoud, B., & Ghersi, F. (2023). Macroeconomic challenges of energy transitions: the case of Algeria (Presented during the 26th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis (Bordeaux, France)). Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN: Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP).

- ElSayed, M.; Aghahosseini, A.; Breyer, C. High cost of slow energy transitions for emerging countries: On the case of Egypt’s pathway options. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, M.; Aghahosseini, A.; Caldera, U.; Breyer, C. Analysing the techno-economic impact of e-fuels and e-chemicals production for exports and carbon dioxide removal on the energy system of sunbelt countries – Case of Egypt. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhla, D.A.; Hassan, M.G.; El Haggar, S. Impact of biomass in Egypt on climate change. Nat. Sci. 2013, 05, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawila, D.; Mondal, A.H.; Kennedy, S.; Mezher, T. Renewable energy readiness assessment for North African countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, M.; Shehata, A.S.; Hassan, A.A.; Kotb, M.A. Renewable solar and wind energies on buildings for green ports in Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 47602–47629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. (2018). Renewable Energy Outlook: Egypt. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

- Esily, R.R.; Chi, Y.; Ibrahiem, D.M.; Chen, Y. Hydrogen strategy in decarbonization era: Egypt as a case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 18629–18647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouaiana, A.; Battisti, A. Multifunction Land Use to Promote Energy Communities in Mediterranean Region: Cases of Egypt and Italy. Land 2022, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatah, A.A.; Hashim, F.A.; Mostafa, R.R.; El-Sattar, H.A.; Kamel, S. Energy management of hybrid PV/diesel/battery systems: A modified flow direction algorithm for optimal sizing design — A case study in Luxor, Egypt. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.H.A.; Khalil, A.; Yehia, M. Modeling alternative scenarios for Egypt 2050 energy mix based on LEAP analysis. Energy 2023, 266, 126615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, J.; Elkarmi, F.; Alasis, E.; Kostas, A. Employment of renewable energy in Jordan: Current status, SWOT and problem analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.A. (2019). Renewables & refugees: A solution for Jordan [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Mississippi].

- Alkhalidi, A.; Alqarra, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A. Renewable energy curtailment practices in Jordan and proposed solutions. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 16, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwashdeh, S.S. Energy sources assessment in Jordan. Results Eng. 2021, 13, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Alsotary, O.; Juaidi, A.; Albatayneh, A.; Alzoubi, A.; Gorjian, S. Potential of Producing Green Hydrogen in Jordan. Energies 2022, 15, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, M., Ekenberg, L., Komendantova, N., Al-Salaymeh, A., & Marashdeh, L. (2022). A Participatory MCDA Approach to Energy Transition Policy Formation. Multicriteria and Optimization Models for Risk, Reliability, and Maintenance Decision Analysis, 79–110. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.; Razem, M. The nexus of gendered practices, energy, and space use: A comparative study of middleclass housing in Pakistan and Jordan. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 83, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C. (2021). Current Barriers and Future Outlooks for Renewable Energy in Lebanon.

- Shehabi, A.; Al-Masri, M. Foregrounding citizen imaginaries: Exploring just energy futures through a citizens’ assembly in Lebanon. Futures 2022, 140, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; McCulloch, N.; Al-Masri, M.; Ayoub, M. From dysfunctional to functional corruption: the politics of decentralized electricity provision in Lebanon. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 86, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, B.; Hamie, S.; Pappas, K.; Roth, J. Examining Lebanon’s Resilience Through a Water-Energy-Food Nexus Lens. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Höffken, J., & Pols, A. (2021). Dilemmas of Energy Transitions in the Global South. Routledge.

- El-Fadel, M.; Chedid, R.; Zeinati, M.; Hmaidan, W. Mitigating energy-related GHG emissions through renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perakis, C., Anagnostopoulos, K., & Jouni, A. (2012). Advancements and external assistance in the fields of renewable energy and energy efficiency in Lebanon. 2012 International Conference on Renewable Energies for Developing Countries (REDEC).

- Machnouk, S., El Houseini, H., Kateb, R., & Stephan, C. (2019). The energy regulation market review, edition 8 – Lebanon. The Law Reviews. Retrieved from https://thelawreviews.co.uk/edition/the-energyregulation-and-markets-review-edition-8/1194563/lebanon.

- Khoury, J.; Mbayed, R.; Salloum, G.; Monmasson, E.; Guerrero, J. Review on the integration of photovoltaic renewable energy in developing countries—Special attention to the Lebanese case. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, K. Drawing Lessons When Objectives Differ? Assessing Renewable Energy Policy Transfer from Germany to Morocco. Politi- Gov. 2015, 3, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C., Günay, C., Gharib, S., & Komendantova, N. (2022). Imagined inclusions into a ‘green modernisation’: local politics and global visions of Morocco’s renewable energy transition. Third World Quarterly, 43(2), 393–413. [CrossRef]

- Chentouf, M.; Allouch, M. Assessment of renewable energy transition in Moroccan electricity sector using a system dynamics approach. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, J., Kadrani, A., Harraki, I. E., & Ezzahid, E. hadj. (2021). Renewable Energy Development in Morocco: Reflections on Optimal Choices through Long-term Bottom-up Modeling. 2021 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET).

- Contreras, J.S.; Ruiz, A.M.; Campos-Celador, A.; Fjellheim, E.M. Energy Colonialism: A Category to Analyse the Corporate Energy Transition in the Global South and North. Land 2023, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, F., Daum, B., Muntschick, J., Knodt, M., Hasse, C., Ott, I., & Niemann, A. (2023). Hydrogen: Fueling EU-Morocco Energy Cooperation? Middle East Policy, 30(3), 37–52. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Fragkos, P. Assessing the energy system impacts of Morocco’s nationally determined contribution and low-emission pathways. Energy Strat. Rev. 2023, 47, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Vera, D. Importance of renewable energy sources and agricultural biomass in providing primary energy demand for Morocco. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 34575–34598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourya, I.; Abderafi, S. Clean technology selection of hydrogen production on an industrial scale in Morocco. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourya, I.; Nabil, N.; Abderafi, S.; Boutammachte, N.; Rachidi, S. Assessment of green hydrogen production in Morocco, using hybrid renewable sources (PV and wind). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 37428–37442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahidi, L.O.; Mechaqrane, A. Energy and economic analysis for the selection of optimal greenhouse design: A case study of the six Morocco’s climatic zones. Energy Build. 2023, 289, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, M., & Azar, A. T. (2021). The complex dynamics of renewable energy innovation system in Tunisia. Design, Analysis, and Applications of Renewable Energy Systems, 121–164. [CrossRef]

- Attig-Bahar, F., Ritschel, U., Akari, P., Abdeljelil, I., & Amairi, M. (2021). Wind energy deployment in Tunisia: Status, Drivers, Barriers and Research gaps—A Comprehensive review. Energy Reports, 7, 7374–7389. [CrossRef]

- Rocher, L., & Verdeil, É. (2013). Energy Transition and/or Revolution in Tunisia. Paper presented at the RGS-IBG Annual International Conference 2013, London, United Kingdom.

- Dridi, N. (2021). Financing sustainable development: the case of renewable energies in Tunisia. International Journal of Global Energy Issues, 43(5/6), 504.

- Fragkos, P.; Zisarou, E. Energy System Transition in the Context of NDC and Mitigation Strategies in Tunisia. Climate 2022, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. (2021). Renewable Readiness Assessment: The Republic of Tunisia. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

- Souissi, A. Optimum utilization of grid-connected renewable energy sources using multi-year module in Tunisia. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Pitas, C.; Christofi, G.; Bué, E.; Francescato, M.G. Grid Integration as a Strategy of Med-TSO in the Mediterranean Area in the Framework of Climate Change and Energy Transition. Energies 2020, 13, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaled, M., Benmessaoud, M. T., & BoudgheneStambouli, A. (2023). High Penetration of Solar Energy to the Algerian Electricity System in the Context of an Energy Roadmap Toward a Sustainable Energy Paradigm by 2030. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry.

- Al Naimat, A.; Liang, D. Substantial gains of renewable energy adoption and implementation in Maan, Jordan: A critical review. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Khadem, S.; Mutule, A.; Papadimitriou, C.; Stanev, R.; Cabiati, M.; Keane, A.; Carroll, P. Identification of Gaps and Barriers in Regulations, Standards, and Network Codes to Energy Citizen Participation in the Energy Transition. Energies 2022, 15, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdeil, É. (2009). Energy transition in Jordanian and Lebanese cities: The case of electricity. In Cities and Energy Transitions: Past, Present, Future (Conference presentation). Autun, France.

- Jehling, M.; Hitzeroth, M.; Brueckner, M. Applying institutional theory to the analysis of energy transitions: From local agency to multi-scale configurations in Australia and Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F. Mapping and understanding the drivers of fuel poverty in emerging economies: The case of Egypt and Jordan. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebratu, D., & Swilling, M. (Eds.). (2019). Transformational Infrastructure for Development of a Wellbeing Economy in Africa.

| Construct | Associated factor for comparative analysis | Construct/Factor description |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional environment | Includes both formal (laws, regulations, policies) and informal (cultural norms, traditions) institutions that shape the energy landscape. It examines how these elements influence economic performance and the trajectory of energy policy. | |

| Regulatory frameworks and policy incentives | Evaluates legal and policy mechanisms that support or hinder the adoption of renewable energy, including investment incentives, innovation, and private sector participation. | |

| Governance structures | Describes the systems and mechanisms through which institutions manage energy sector operations, focusing on reducing transaction costs and facilitating effective transactions. | |

| Governance efficacy and efficiency | Assesses the ability of governance structures to manage resources efficiently, reduce transaction costs, and adapt to changing energy landscapes. | |

| Institutional change and adaptability | Examines how institutions in the MENA region are responding to internal changes and external pressures, including global energy trends and sustainability goals. | |

| Institutional flexibility and innovation | Examines the capacity for institutional change in response to technological advances and environmental challenges, highlighting the role of innovation in energy policies and practices. | |

| Social capital and collective action | Assesses the impact of social relationships and collaborative efforts in advancing renewable energy projects and policies, emphasizing community engagement in the energy transition. | |

| Stakeholder engagement and collaborative governance | Considers the extent to which different stakeholders (government, private sector, civil society) are involved in energy governance and the effectiveness of collaborative approaches to energy challenges. | |

| Cultural and social norms | Prevailing lifestyles, traditions, and interrelationships that act as drivers or inhibitors of energy transitions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).