Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Period

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Study Tools and Data Collection

2.4. Sampling and Sample Size

2.5. Outcomes and Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organization WH. Guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in self-medication. World Health Organization; 2000. p. WHO/EDM/QSM/00.1.

- Ruiz, M. Risks of Self-Medication Practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5: 315–323. [CrossRef]

- Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Trujillo-Moreno, M.J.; Pérez-Acosta, A.M.; Feliciano-Alfonso, J.E.; Calderon-Ospina, C.A.; Soler, F. Definition of self-medication: a scoping review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2022, 13, 20420986221127501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). World Drug Report. Vienna. 2012. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/statistics/drug.

- Kumari, R.; Kiran, K.; Kumar, D.; Bahl, R.; Gupta, R. Study of knowledge and practices of self-medication among medical students at Jammu. Jms Skims 2012, 15(2), 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadifar, M.; Behzadifar, M.; Aryankhesal, A.; Ravaghi, H.; Baradaran, H.R.; Sajadi, H.S.; et al. Prevalence of self-medication in university students: systematic review and meta-analysis. East Mediterr Health J 2020, 26(7), 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrais, P.S.; Fernandes, M.E.; Pizzol, T.D.; Ramos, L.R.; Mengue, S.S.; Luiza, V.L.; Tavares, N.U.; Farias, M.R.; Oliveira, M.A.; Bertoldi, A.D. Prevalence of self-medication in Brazil and associated factors. Rev Saude Publica 2016, 50, 13s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, L.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Angelillo, I.F. Self-medication practices among parents in Italy. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 580650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, A.; Logaraj, M. Prevalence and determinants of self-medication use among the adult population residing in suburban areas near Chennai, Tamil Nadu. J Family Med Prim Care 2021, 10, 1835–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, M.I.; Rasool, G.; Tabassum, R.; Shaheen, M.; Siddiqullah; Shujauddin, M. Prevalence and pattern of self-medication in Karachi: A community survey. Pak J Med Sci 2015, 31, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Aryal, B. Exploration of self-medication practice in Pokhara valley of Nepal. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seam, M.O.R.; Bhatta, R.; Saha, B.L.; Das, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Uddin, S.M.N.; Karmakar, P.; Choudhuri, M.S.K.; Sattar, M.M. Assessing the Perceptions and Practice of Self-Medication among Bangladeshi Undergraduate Pharmacy Students. Pharmacy (Basel) 2018, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ira, I.J. Present condition of self-medication among the general population of Comilla district, Bangladesh. The Pharma Innovation 2015, 4, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Moonajilin, M.S.; Mamun, M.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Mahmud, M.F.; Al Mamun, A.H.M.S.; Rana, M.S.; Gozal, D. Prevalence and Drivers of Self-Medication Practices among Savar Residents in Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020, 13, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, M.A.; Biswas, K. A cross-sectional study regarding the knowledge, attitude, and awareness about self-medication among Bangladeshi people. Health Policy and Technology 2023, 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M. R.; Bert, F.; Passi, S.; Stillo, M.; Galis, V.; Manzoli, L.; Siliquini, R. Use of self-medication among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, L.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F. M.; Burgerhof, J. G.; Mechtler, R.; Deschepper, R.; Tambic-Andrasevic, A.; ... Birkin, J. Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 452. [CrossRef]

- Demissie, F.; Ereso, K.; Paulos, G. Self-medication practice with antibiotics and its associated factors among the community of Bule-Hora Town, South West Ethiopia. Drug, Healthc. Patient Saf. 2022; 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S. Self-medications among higher educated population in Bangladesh: an email-based exploratory study. Internet J. Health 2007, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Regulatory Assessment of Medicinal Products for Use in Self-Medication. World Health Organization, 2000.

- Bennadi, D. Self-medication: A current challenge. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2013, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montastruc, J. L.; Bondon-Guitton, E.; Abadie, D.; Lacroix, I.; Berreni, A.; Pugnet, G.; Durrieu, G.; Sailler, L.; Giroud, J. P.; Damase-Michel, C.; Montastruc, F. Pharmacovigilance, risks, and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapies 2016, 71, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M. M. Factors contributing to the purchase of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs in Bangladesh: an empirical study. Internet J. Third World Med. 2008, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Montastruc, J. L.; Bondon-Guitton, E.; Abadie, D.; Lacroix, I.; Berreni, A.; Pugnet, G.; Durrieu, G.; Sailler, L.; Giroud, J. P.; Damase-Michel, C.; Montastruc, F. Pharmacovigilance, risks, and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapie 2016, 71, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Roy, M. N.; Manik, M. I. N.; et al. Self-medicated antibiotics in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in the Rajshahi City. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Daily Star. Take steps to stop sale of antibiotic drugs without prescriptions, HC tells govt, 2019. Available from: https://www.thedailystar.net/city/take-steps-to-stop-sale-of-antibiotics-without-prescriptions-1734625.

- Gajic, A.; Herrmann, R.; Salzberg, M. The international quality requirements for the conduct of clinical studies and the challenges for study centers to implement them. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 1305–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, A. D.; Bifftu, B. B.; Mekonnen, H. S. Self-medication practice and associated factors among adult household members in Meket district, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, D.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Fernández-Álvarez, J.; Cipresso, P.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Riva, G.; Botella, C. Affect recall bias: Being resilient by distorting reality. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Khatony, A.; Rahmani, E. Prevalence of self-medication among the elderly in Kermanshah, Iran. Global J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Marma, K. K. S.; Rashid, A.; Tarannum, N.; Das, S.; Chowdhury, T.; ... Mistry, S. K. Risk factors associated with self-medication among the indigenous communities of Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0269622. [CrossRef]

- Jember, E.; Feleke, A.; Debie, A.; Asrade, G. Self-medication practices and associated factors among households at Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassali, M. A.; Shafie, A. A.; Al-Qazaz, H.; Tambyappa, J.; Palaian, S.; Hariraj, V. Self-medication practices among the adult population attending community pharmacies in Malaysia: an exploratory study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2011, 33, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekeba, A.; Ayele, Y.; Negash, B.; Gashaw, T. Extent of and Factors Associated with Self-Medication among Clients Visiting Community Pharmacies in the Era of COVID-19: Does It Relieve the Possible Impact of the Pandemic on the Health-Care System? Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 4939–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, P.; Sharma, S.; Ukey, U.; Sonpimpale, B.; Ughade, S.; Narlawar, U.; ... Gaikwad Jr, S. D. Prevalence, Pattern, and Reasons for Self-Medication: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study From Central India. Cureus 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Araia, Z. Z.; Gebregziabher, N. K.; Mesfun, A. B. Self-medication practice and associated factors among students of Asmara College of Health Sciences, Eritrea: a cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kifle, Z. D.; Mekuria, A. B.; Anteneh, D. A.; Enyew, E. F. Self-medication practice and associated factors among private health sciences students in Gondar Town, North West Ethiopia. A Cross-Sectional Study. Inquiry 2021, 58, 00469580211005188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M. A.; Francisco, P. M. S. B.; Costa, K. S.; Barros, M. B. de A. Automedicação em idosos residentes em Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil: prevalência e fatores associados. Cad. Saúde Pública. 2012, 28, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathewos, T.; Daka, K.; Bitew, S.; Daka, D. Self-medication practice and associated factors among adults in Wolaita Soddo town, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Infect. Control 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vali, L.; Pourreza, A.; Foroushani, A. R.; Sari, A. A.; Honarm, D. H. An Investigation on Inappropriate Medication Applied among Elderly Patients. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 16, 819–825. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Mangal, A.; Yadav, G.; Raut, D.; Singh, S. Prevalence and pattern of self-medication practices in an urban area of Delhi, India. Med. J. Dr. DY Patil Univ. 2015, 8(1), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho Filho, J. M.; Marcopito, L. F.; Castelo, A. Medication use patterns among elderly people in an urban area in Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2022 Apr 21]; 38(4), 557–564.

- Paavilainen, E.; Lehti, K.; Åstedt-Kurki, P.; Tarkka, M. T. Family functioning assessed by family members in Finnish families of heart patients. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2006, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T. T.; Hoang, P. N.; Pham, H. V.; Nguyen, D. N.; Bui, H. T. T.; Nguyen, A. T.; Do, T. D.; Dang, N. T.; Dinh, H. Q.; Truong, D. Q.; Le, T. A. Routine Medical Check-Up and Self-Treatment Practices among Community-Dwelling Living in a Mountainous Area of Northern Vietnam. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, TK. Quack: Their Role in Health Sector. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2008. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1292712.

| Variables | Total N = 1320 |

Self-medication | χ2 | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 672 | 50.9 | 328 | 48.8 | 344 | 51.2 | 55.38 | <0.001 |

| Female | 648 | 49.1 | 447 | 69.0 | 201 | 31.0 | ||

| Age in years | ||||||||

| ≤30 | 915 | 69.3 | 569 | 62.2 | 346 | 37.8 | 16.22 | <0.001 |

| 31 to 60 | 361 | 27.3 | 180 | 49.9 | 181 | 50.1 | ||

| >60 | 44 | 3.3 | 26 | 59.1 | 18 | 40.9 | ||

| Years of schooling | ||||||||

| <10 years 10 years 11-12 years >12 years No Schooling |

510 | 38.6 | 315 | 61.8 | 195 | 38.2 | 43.31 | <0.001 |

| 425 | 32.2 | 254 | 59.8 | 171 | 40.2 | |||

| 172 | 13.0 | 100 | 58.1 | 72 | 41.9 | |||

| 92 | 7.0 | 25 | 27.2 | 67 | 72.8 | |||

| 121 | 9.2 | 81 | 66.9 | 40 | 33.1 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Unmarried Divorced/Widowed Married |

682 | 51.7 | 406 | 59.5 | 276 | 40.5 | 1.09 | 0.580 |

| 21 | 1.6 | 14 | 66.7 | 7 | 33.3 | |||

| 617 | 46.7 | 355 | 57.5 | 262 | 42.5 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Farmer | 63 | 4.8 | 23 | 36.5 | 40 | 63.5 | 107.41 | <0.001 |

| Day labor | 76 | 5.8 | 50 | 65.8 | 26 | 34.2 | ||

| House wife | 307 | 23.3 | 231 | 75.2 | 76 | 24.8 | ||

| Business | 104 | 7.9 | 27 | 26.0 | 77 | 74.0 | ||

| Private | 49 | 3.7 | 18 | 36.7 | 31 | 63.3 | ||

| Othersa | 690 | 52.3 | 412 | 59.7 | 278 | 40.3 | ||

| Government | 31 | 2.3 | 14 | 45.2 | 17 | 54.8 | ||

| Household income per month | ||||||||

| <15000 BDT | 938 | 71.1 | 586 | 62.5 | 352 | 37.5 | 20.57 | <0.001 |

| 15000-30000 BDT | 360 | 27.3 | 181 | 50.3 | 179 | 49.7 | ||

| >30000 BDT | 22 | 1.7 | 8 | 36.4 | 14 | 63.6 | ||

| Residence | ||||||||

| Urban area | 161 | 12.2 | 74 | 46.0 | 87 | 54.0 | 12.30 | <0.001 |

| Rural area | 1159 | 87.8 | 701 | 60.5 | 458 | 39.5 | ||

| Religion | ||||||||

| Islam | 1156 | 87.6 | 692 | 59.9 | 464 | 40.1 | 5.07 | 0.024 |

| Othersb | 164 | 12.4 | 83 | 50.6 | 81 | 49.4 | ||

| Family members | ||||||||

| 3-4 members 5 - 6 members Above 6 members |

592 | 44.8 | 322 | 54.4 | 270 | 45.6 | 24.83 | <0.001 |

| 553 | 41.9 | 321 | 58.0 | 232 | 42.0 | |||

| 175 | 13.3 | 132 | 75.4 | 43 | 24.6 | |||

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Smoker Non-Smoker |

187 | 14.2 | 76 | 40.6 | 111 | 59.4 | 29.35 | <0.001 |

| 1133 | 85.8 | 699 | 61.7 | 434 | 38.3 | |||

| Health insurance | ||||||||

| Yes No |

79 | 6.0 | 30 | 38.0 | 49 | 62.0 | 14.91 | <0.001 |

| 1241 | 94.0 | 745 | 60.0 | 496 | 40.0 | |||

| Member of a social group | ||||||||

| Yes No |

249 | 18.9 | 105 | 42.2 | 144 | 57.8 | 34.65 | <0.001 |

| 1071 | 81.1 | 670 | 62.6 | 401 | 37.4 | |||

| Health status check (after every 6 months) | ||||||||

| Yes No |

223 | 16.9 | 98 | 43.9 | 125 | 56.1 | 24.14 | <0.001 |

| 1097 | 83.1 | 677 | 61.7 | 420 | 38.3 | |||

| Knowledge of drug used | ||||||||

| Adequate Inadequate |

23 | 1.7 | 8 | 34.8 | 15 | 65.2 | 5.53 | 0.019 |

| 1297 | 98.3 | 767 | 59.1 | 530 | 40.9 | |||

| Present illness | ||||||||

| Yes No |

483 | 36.6 | 246 | 50.9 | 237 | 49.1 | 19.02 | <0.001 |

| 837 | 63.4 | 529 | 63.2 | 308 | 36.8 | |||

| Under treatment | ||||||||

| Yes | 473 | 35.8 | 240 | 50.7 | 233 | 49.3 | 19.33 | <0.001 |

| No | 847 | 64.2 | 535 | 63.2 | 312 | 36.8 | ||

| Most frequent healing methods | ||||||||

| Modern Homeopathy Herbal Ayurvedic Quackery |

873 | 66.1 | 563 | 64.5 | 310 | 35.5 | 37.24 | <0.001 |

| 284 | 21.5 | 139 | 48.9 | 145 | 51.1 | |||

| 69 | 5.2 | 34 | 49.3 | 35 | 50.7 | |||

| 19 | 1.4 | 8 | 42.1 | 11 | 57.9 | |||

| 75 | 5.7 | 31 | 41.3 | 44 | 58.7 | |||

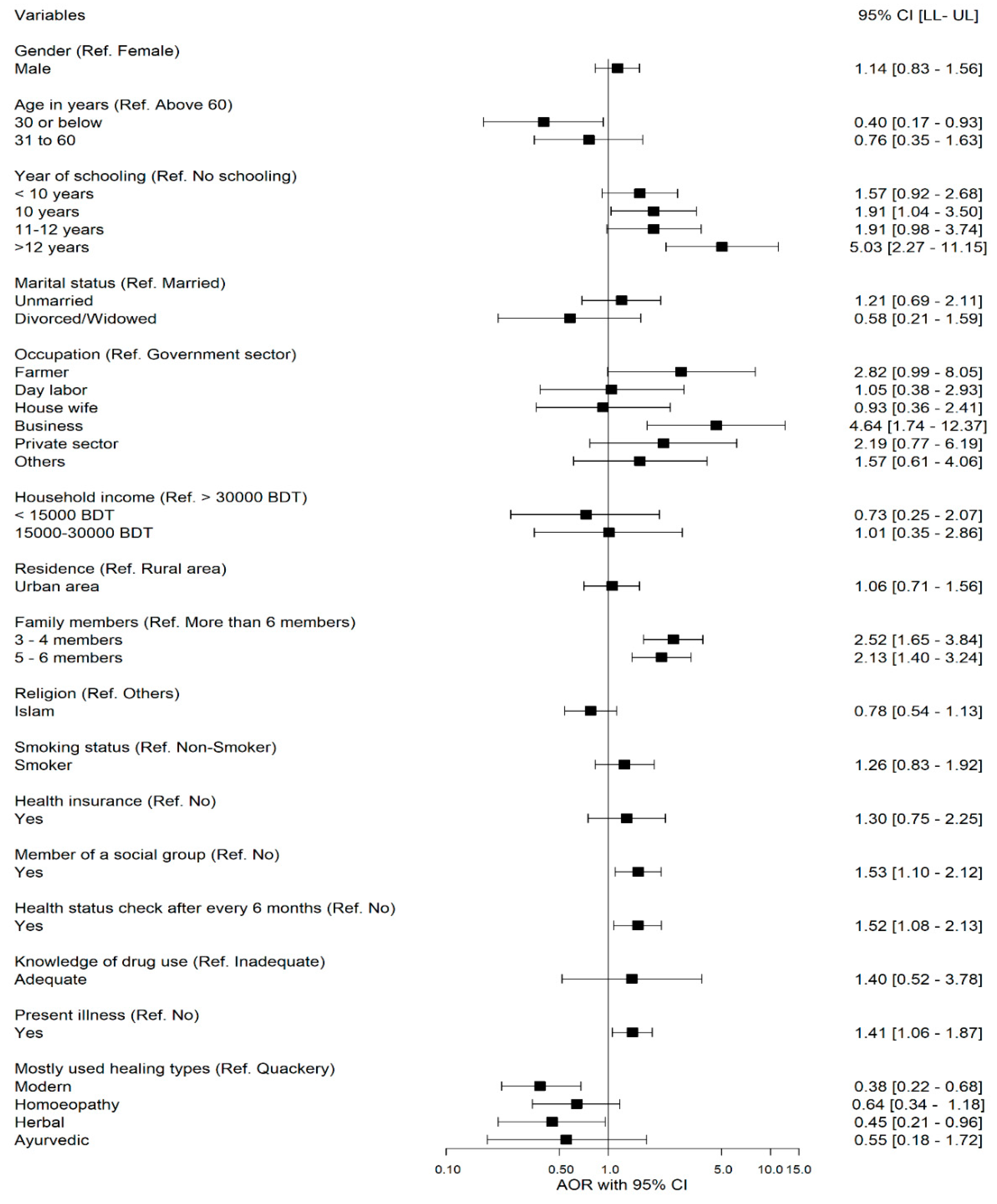

| Variables & Categories | p-value | COR 95% CI [LL- UL] |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Ref. (Female) | ||

| Male | <0.001 | 2.33 [1.86- 2.92] |

| Age (Ref. >60 Years) | ||

| ≤30 Years | 0.680 | 0.88 [0.48- 1.63] |

| 31 to 60 years | 0.250 | 1.45 [0.77- 2.74] |

| Years of schooling (Ref. No schooling) | ||

| < 10 years | 0.290 | 1.25 [0.83- 1.91] |

| 10 years | 0.153 | 1.36 [0.89- 2.09] |

| 11-12 years | 0.128 | 1.46 [0.90- 2.37] |

| >12 years | <0.001 | 5.43 [2.99- 9.84] |

| Marital status (Ref. Married) | ||

| Unmarried | 0.466 | 0.92 [0.74- 1.15] |

| Divorced/Widowed | 0.407 | 0.68 [0.27- 1.70] |

| Occupation (Ref. Government sector) | ||

| Farmer | 0.420 | 1.43 [0.60- 3.43] |

| Day labor | 0.051 | 0.43 [0.18- 1.00] |

| House wife | 0.001 | 0.27 [0.13- 0.58] |

| Business | 0.044 | 2.35 [1.02- 5.40] |

| Private sector | 0.454 | 1.42 [0.57- 3.54] |

| Others | 0.111 | 0.56 [0.27- 1.15] |

| Household income (Ref. >30000 BDT) | ||

| <15000 BDT | 0.017 | 0.34 [0.14- 0.83] |

| >15000-30000 BDT | 0.210 | 0.57 [0.23- 1.38] |

| Residence (Ref. Rural area) | ||

| Urban area | 0.001 | 1.80 [1.29- 2.51] |

| Family members (Ref. More than 6 members) | ||

| 3 - 4 members | <0.001 | 2.57 [1.76- 3.77] |

| 5 - 6 members | <0.001 | 2.22 [1.51- 3.26] |

| Religion (Ref. Others) | ||

| Islam | 0.025 | 0.69 [0.50- 0.95] |

| Smoking status (Ref. Non-Smoker) | ||

| Smoker | <0.001 | 2.35 [1.72- 3.23] |

| Health insurance (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.45 [1.54- 3.92] |

| Member of a social group (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.29 [1.73- 3.03] |

| Health status check (after every 6 months) (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.06 [1.54- 2.75] |

| Knowledge of drug used (Ref. Inadequate) | ||

| Adequate | 0.024 | 2.71 [1.14- 6.45] |

| Present illness (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 1.66 [1.32- 2.08] |

| Most frequent healing methods (Ref. Quackery) | ||

| Modern | <0.001 | 0.39 [0.24- 0.63] |

| Homeopathy | 0.241 | 0.74 [0.44- 1.23] |

| Herbal | 0.339 | 0.73 [0.38- 1.40] |

| Ayurvedic | 0.951 | 0.97 [0.35- 2.69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).