Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals

2.1. Servitization and digital servitization

2.2. Service-oriented and data-driven business models

2.3. Product-service systems (PSSs)

2.4. Ecosystems

3. Research methodology

| Industry | Positions / Roles | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel Solutions | Production Manager | >249 |

| Stainless Steel Solutions | Chief Executive Officer | <50 |

| Stainless Steel Solutions | Construction | <50 |

| Metal and Tube Technology | Attorney & Division Manager | <250 |

| Construction Industry | Production Manager | >249 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <250 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <50 |

| Automotive Solutions | Head of Purchasing | <250 |

| Stainless Steel Solutions | Chief Executive Officer | <50 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <50 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <10 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | >249 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <250 |

| Metal Processing Company | Chief Executive Officer | <250 |

| Metal Processing Company | Operating Manager | <50 |

| Solution Provider for Metal Industry | Chief Executive Officer | <10 |

| Nr. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Have you ever heard of service-oriented and data-driven business models? |

| 2 | Describe briefly what you understand by a service-oriented and data-driven business model |

| 3 | To what extent did you come into contact with service-oriented and data-driven business models and ecosystems? |

| 4 | What business models are currently used in your company’s core value creation? |

| 5 | In your opinion, what are the main reasons, why so few data-driven & service-oriented business models have been established in the market? |

| 6 | What challenges / difficulties / risks do you see as a company when offering / using service-oriented and data-driven business models? |

| 7 | What challenges / difficulties / risks do you see as a company when using / participating in ecosystems in the context of service-oriented and data-driven business models? |

| 8 | Do you see a need to change your business model? |

| 9 | Is there a need for action prior to implementation and participation in the value network (e.g., technical infrastructure, staff know-how, organization...)? |

| 10 | What skills does your company need to implement these service-oriented business models and participate in the multilateral and collaborative ecosystems? |

| 11 | Can you imagine collaborating with external partners? |

| 12 | Can you imagine bringing missing expertise into the company via external cooperations (e.g., in the business ecosystem or with start-ups)? |

| 13 | Can you currently observe changes in ecosystems? If so, how would you assess them in the future / what changes do you expect in the future? |

| 14 | In your opinion, what requirements and conditions do companies need to meet to be able to offer / use service-oriented and data-driven business models? |

| 15 | What requirements and conditions for ecosystems do you consider relevant for your company? |

4. Results

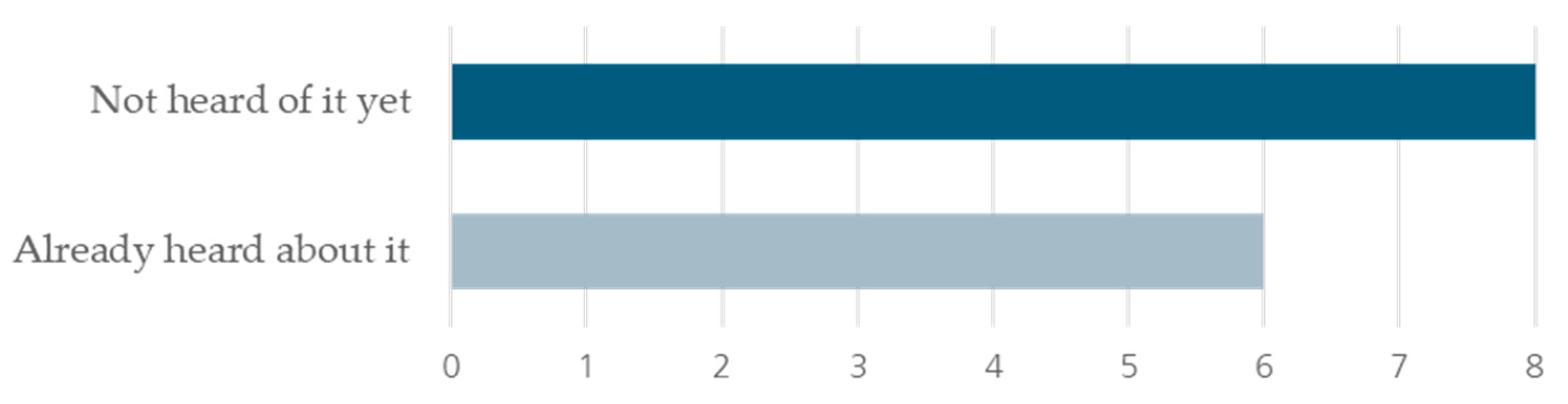

4.1. Question 1: Have you ever heard of service-oriented and data-driven business models?

4.2. Question 2: Describe briefly what you understand by a service-oriented and data-driven business model

4.3. Question 3: To what extent did you come into contact with service-oriented and data-driven business models and ecosystems?

4.4. Question 4: What business models are currently used in your company’s core value creation?

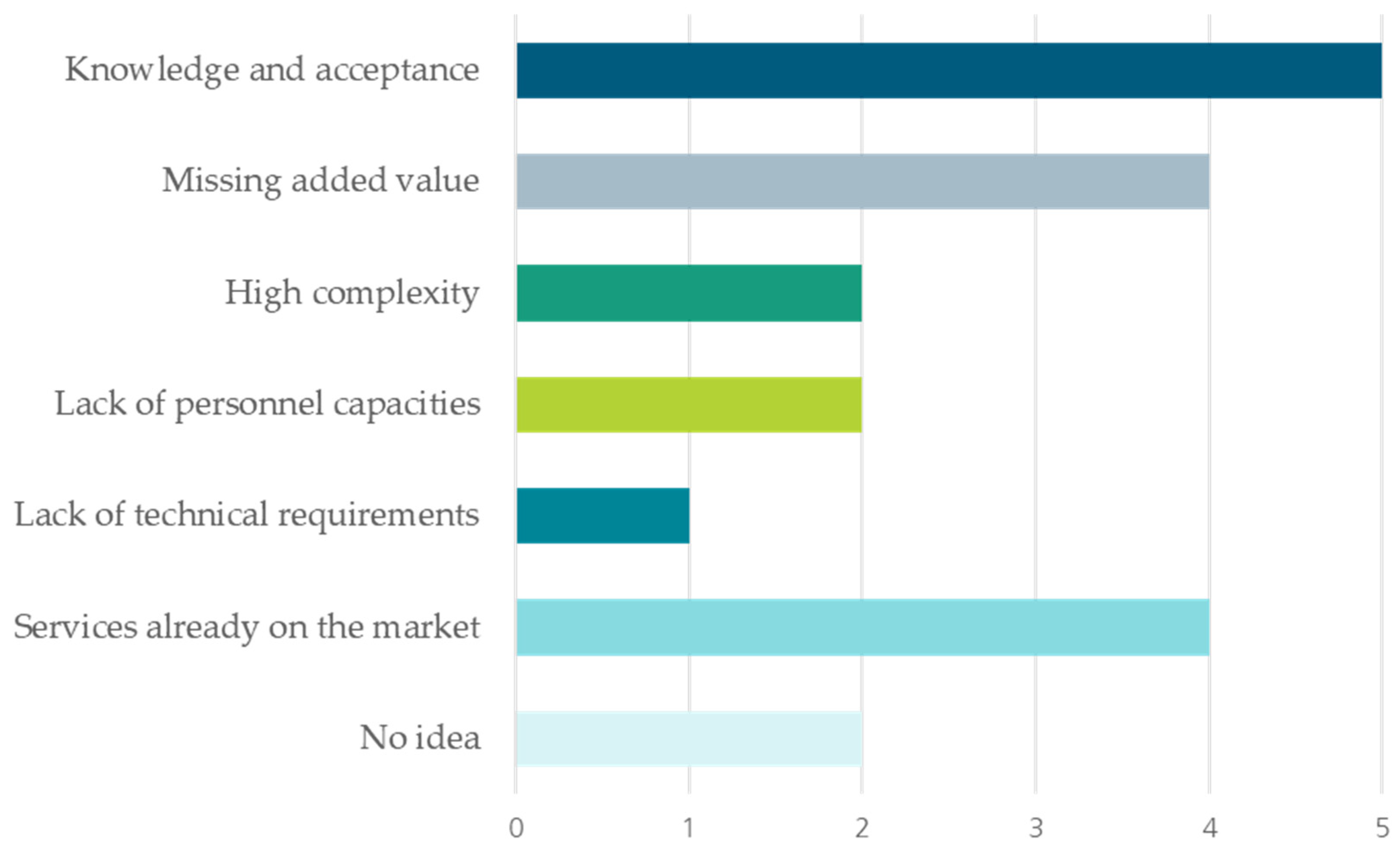

4.5. Question 5: In your opinion, what are the main reasons, why so few data-driven & service-oriented business models have been established in the market?

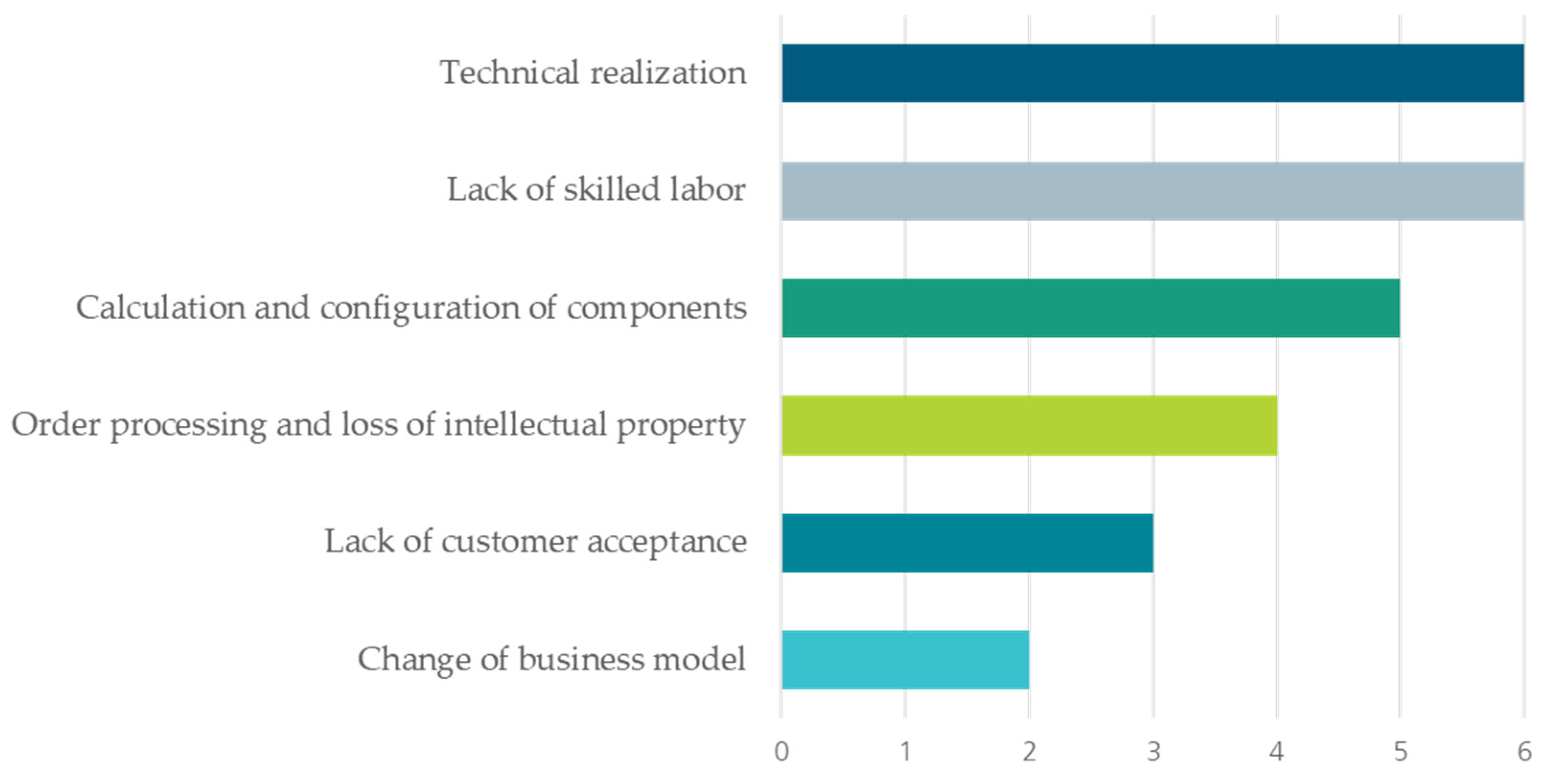

4.6. Question 6: What challenges / difficulties / risks do you see as a company when offering / using service-oriented and data-driven business models?

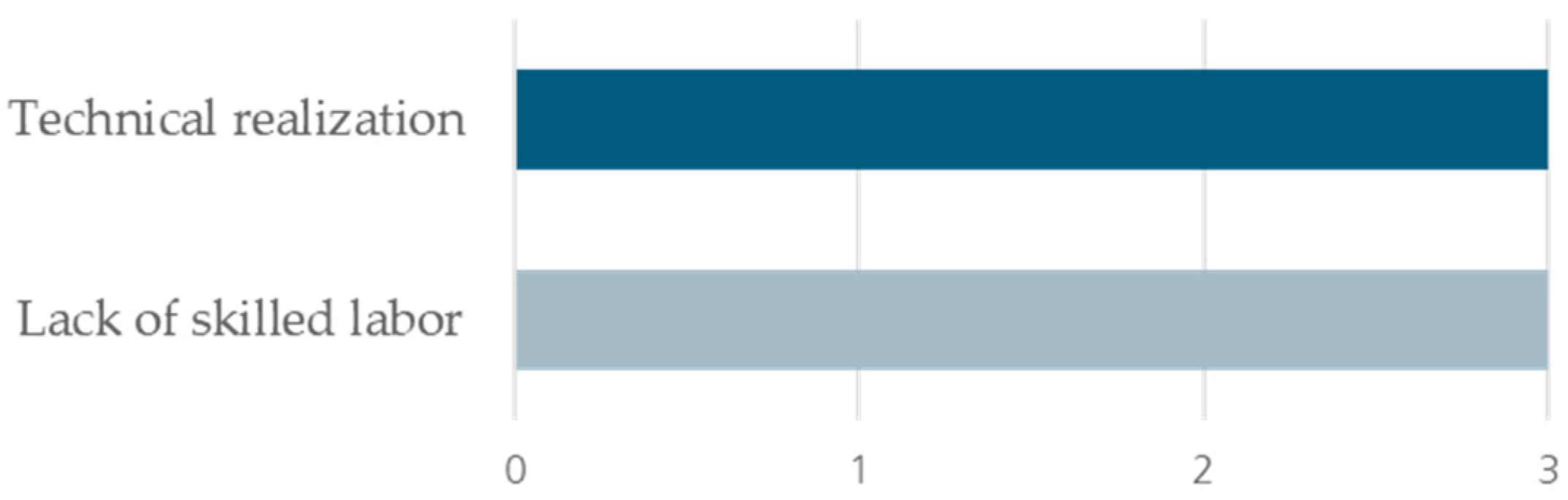

4.7. Question 7: What challenges / difficulties / risks do you see as a company when using / participating in ecosystems in the context of service-oriented and data-driven business models?

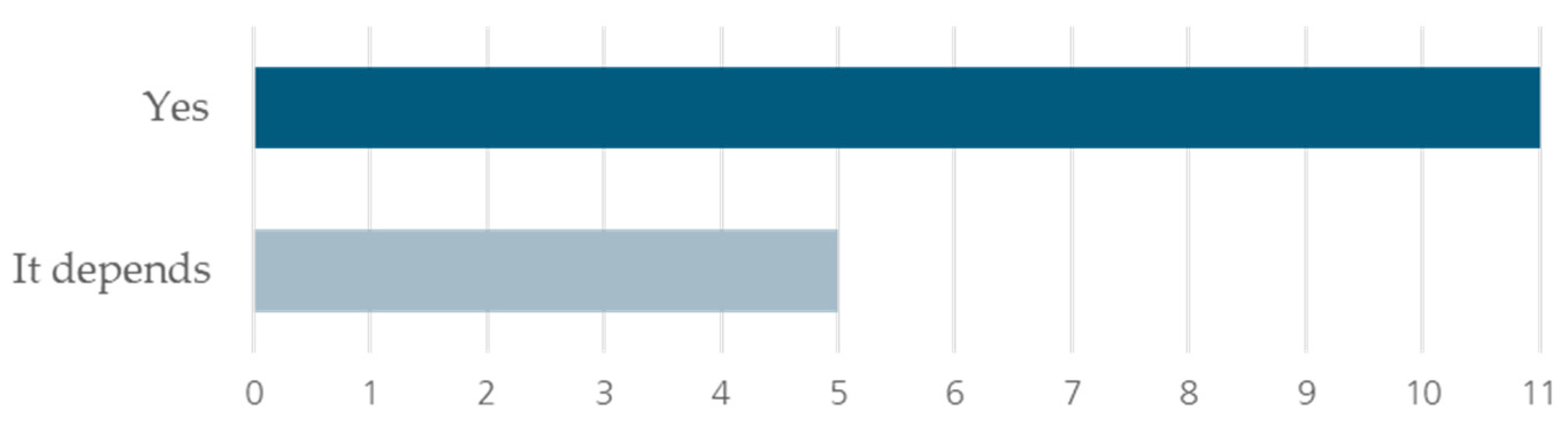

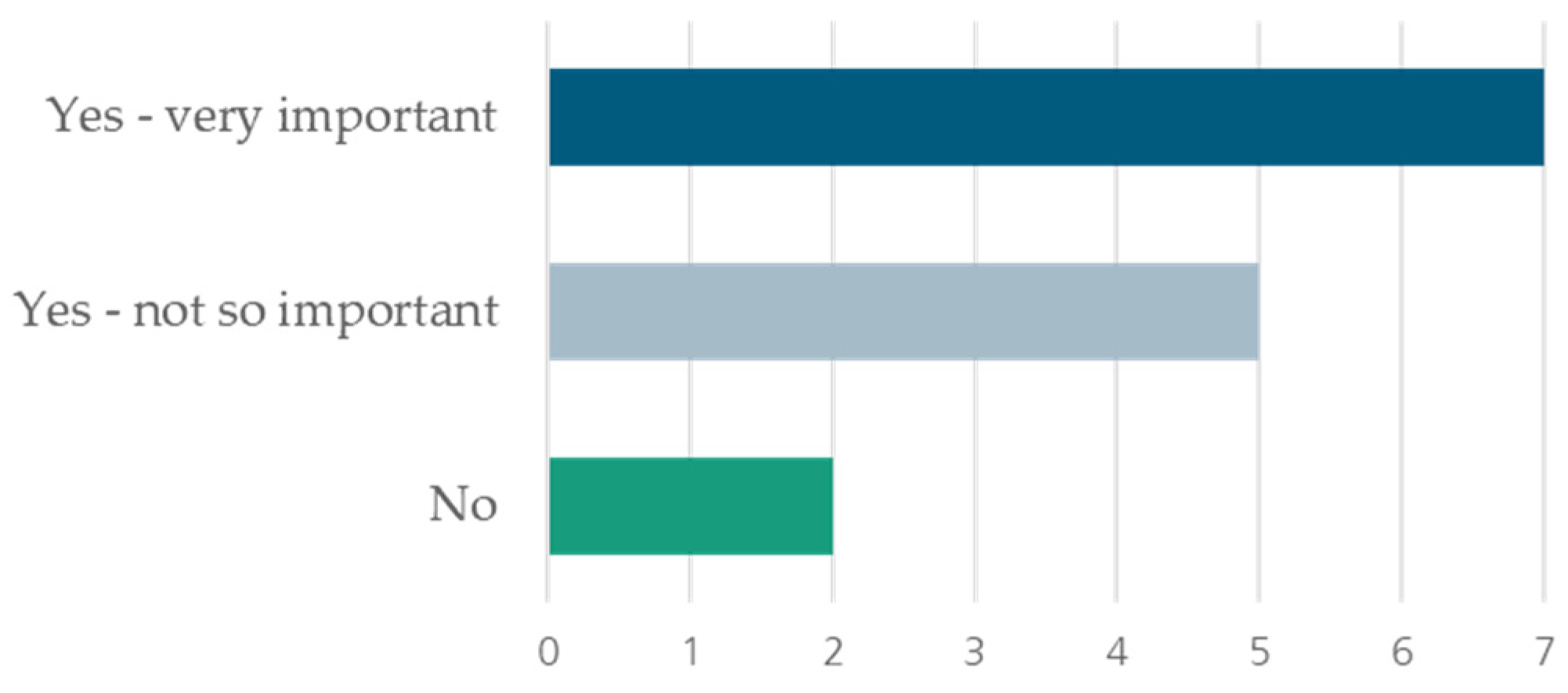

4.8. Question 8: Do you see a need to change your business model?

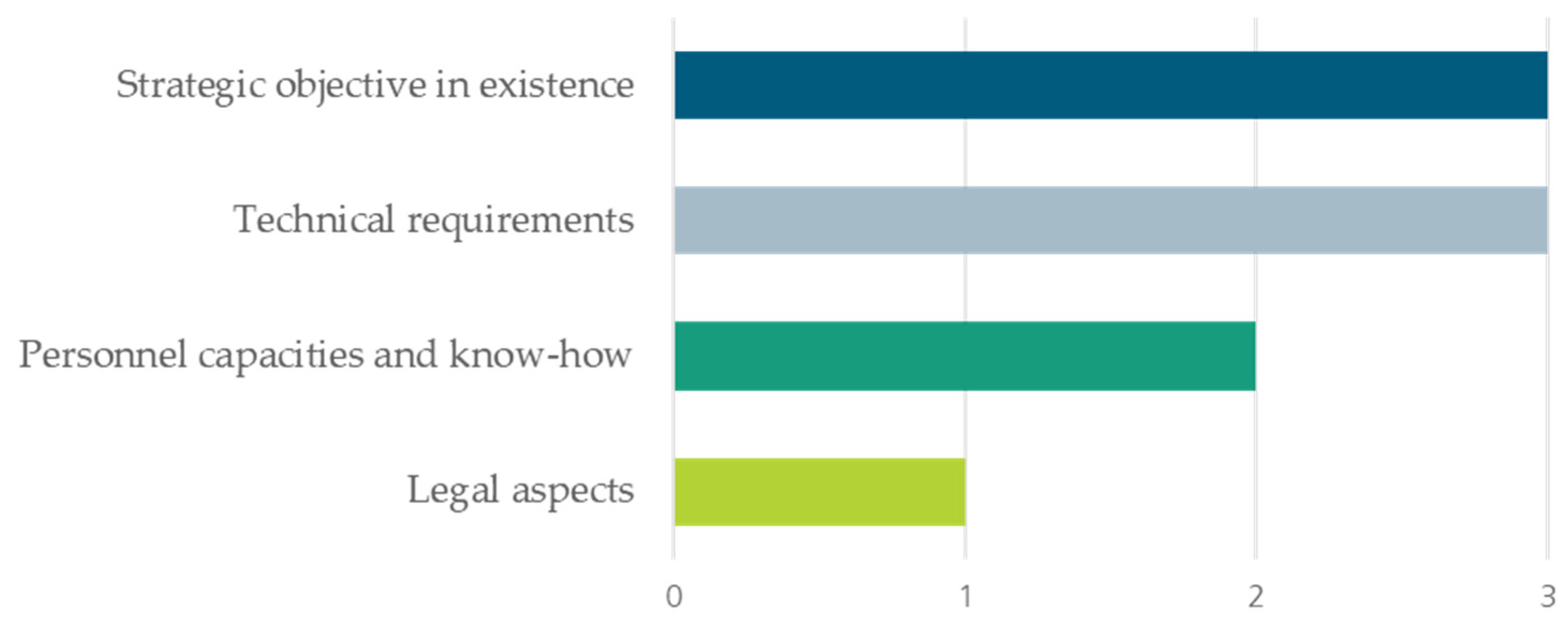

4.9. Question 9: Is there a need for action prior to implementation and participation in the value network (e.g., technical infrastructure, staff know-how, organization...)?

4.10. Question 10: What skills does your company need to implement these service-oriented business models and participate in the multilateral and collaborative ecosystems?

4.11. Question 11 & 12: Can you imagine collaborating with external partners? & Can you imagine bringing missing expertise into the company via external cooperations (e.g., in the business ecosystem or with start-ups)?

4.12. Question 13: Can you currently observe changes in ecosystems? If so, how would you assess them in the future / what changes do you expect in the future?

4.13. Question 14: In your opinion, what requirements and conditions do companies need to meet to be able to offer / use service-oriented and data-driven business models?

4.14. Question 15: What requirements and conditions for ecosystems do you consider relevant for your company?

5. Conclusion

5.1. Creating awareness and understanding:

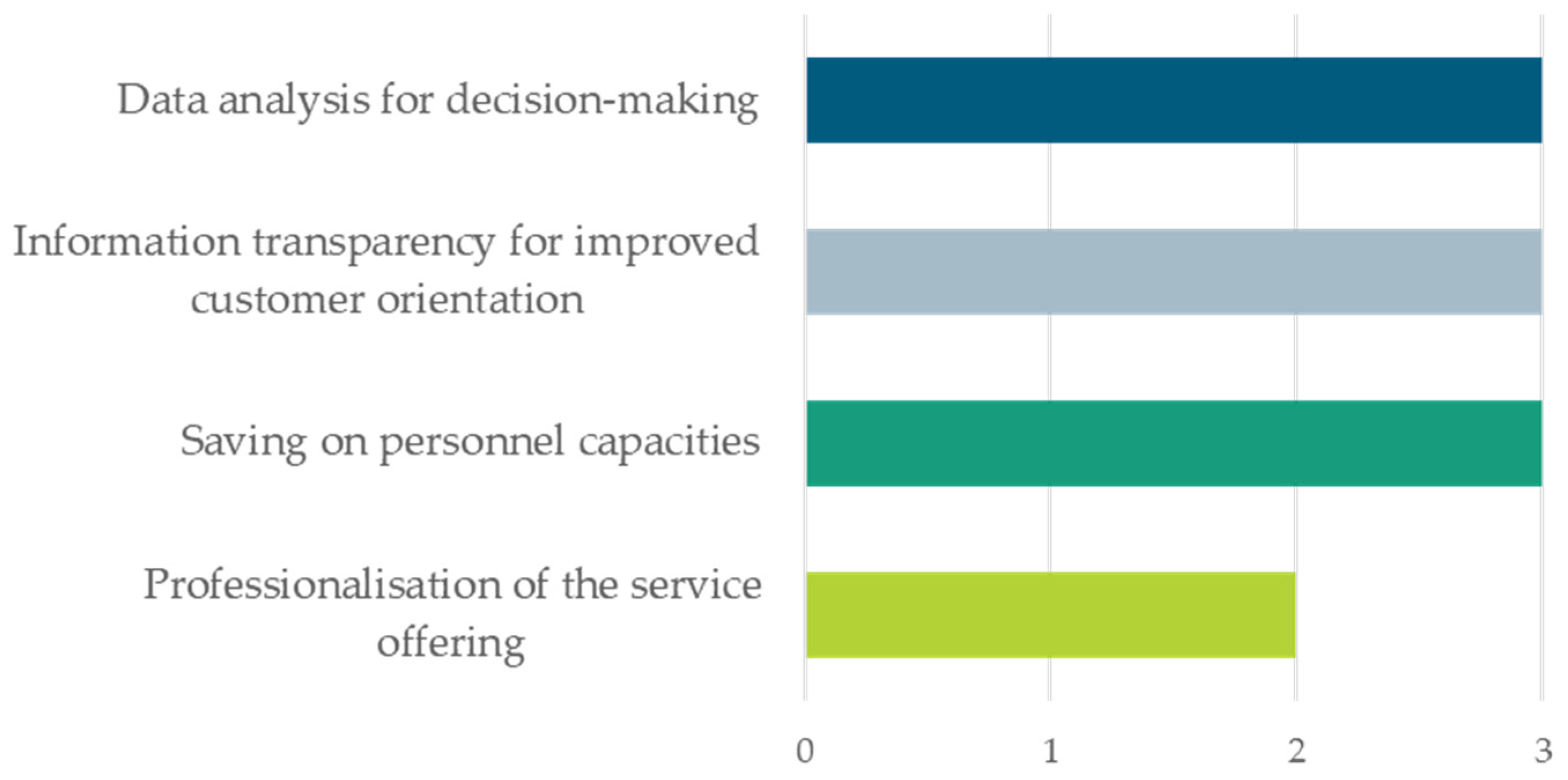

5.2. Recognizing added value:

5.3. Increase company maturity:

5.4. Understanding the change process:

6. Practical and Research Implication

6.1. Practical Implication:

6.2. Research Implication:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Backhaus, K.; Becker, J.; Beverungen, D.; Frohs, M.; Knackstedt, R.; Müller, O.; Steiner, M.; Weddeling, M. Vermarktung hybrider Leistungsbündel; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; ISBN 978-3-642-12829-5. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition. Harvard Business Review 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benedettini, O. Structuring Servitization-Related Capabilities: A Data-Driven Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, C.; Bieger, T. Customer value: Kundenvorteile schaffen Unternehmensvorteile, 2., aktualisierte Aufl.; Thexis; mi-Fachverl.: St. Gallen, Landsberg am Lech, Heidelberg, 2006, ISBN 978-3-636-03081-8.

- Bruhn, M.; Hadwich, K. Service Business Development – Entwicklung und Durchsetzung serviceorientierter Geschäftsmodelle. In Service Business Development; Bruhn, M., Hadwich, K., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2018; pp 3–40, ISBN 978-3-658-22423-3.

- Nippa, M. Geschäftserfolg produktbegleitender Dienstleistungen durch ganzheitliche Gestaltung und Implementierung. In Management produktbegleitender Dienstleistungen; Lay, G., Nippa, M., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 1–18. ISBN 3-7908-1567-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, M.; Thomas, O. Looking beyond the rim of one’s teacup: a multidisciplinary literature review of Product-Service Systems in Information Systems, Business Management, and Engineering & Design. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 51, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.J.; van Halen, C.J.; te Riele, H.R.; Rommens, P.J. Product Service systems, Ecological and Economic Basics, 1999.

- Tukker, A. Eight types of product–service system: eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus Strat Env 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI. Product-Service-Systeme. Available online: https://www.ressourcedeutschland. de/werkzeuge/loesungsentwicklung/strategien-massnahmen/produkt-servicesysteme/#:~: text=Ein%20Produkt%2DService%2DSystem%20(,gemeinsam%20einen%20Nutzerbedarf%20 zu%20erf%C3%BCllen (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. European Management Journal 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Dong, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhang, Y. The impact of servitization on manufacturing firms’ market power: empirical evidence from China. JBIM 2023, 38, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Rabetino, R.; Einola, S.; Parida, V.; Patel, P. Unfolding the digital servitization path from products to product-service-software systems: Practicing change through intentional narratives. Journal of Business Research 2021, 137, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Anteil der KMU in Deutschland an allen Unternehmen nach Wirtschaftszweigen im Jahr 2020. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/731918/umfrage/anteil-der-kmu-in-deutschland-an-allen-unternehmen-nach-wirtschaftszweigen/ (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Rudnicka, J. Anteil der KMU in Deutschland an allen Unternehmen nach Wirtschaftszweigen 2020. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/731918/umfrage/anteil-der-kmu-in-deutschland-an-allen-unternehmen-nach-wirtschaftszweigen/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- IFM Bonn. Mittelstand im Einzelnen. Available online: https://www.ifm-bonn.org/statistiken/mittelstand-im-einzelnen/unternehmensbestand (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Anteile Kleine und Mittlere Unternehmen 2021 nach Größenklassen in %. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Unternehmen/Kleine-Unternehmen-Mittlere-Unternehmen/Tabellen/wirtschaftsabschnitte-insgesamt.html?nn=208440 (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Münch, C.; Marx, E.; Benz, L.; Hartmann, E.; Matzner, M. Capabilities of digital servitization: Evidence from the socio-technical systems theory. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 176, 121361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Benedettini, O.; Kay, J.M. The servitization of manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2009, 20, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamperti, S.; Cavallo, A.; Sassanelli, C. Digital Servitization and Business Model Innovation in SMEs: A Model to Escape From Market Disruption. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, C.; Gotsch, M. Digitalized Product-Service Systems in Manufacturing Firms: A Case Study Analysis. Research-Technology Management 2015, 58, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Baines, T. Service implementation in manufacturing: An organisational transformation perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 2017, 192, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Visnjic, I.; Parida, V.; Zhang, Z. On the road to digital servitization – The (dis)continuous interplay between business model and digital technology. IJOPM 2021, 41, 694–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawiarska, E.; Szwajca, D.; Matusek, M.; Wolniak, R. Diagnosis of the Maturity Level of Implementing Industry 4.0 Solutions in Selected Functional Areas of Management of Automotive Companies in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetino, R.; Harmsen, W.; Kohtamäki, M.; Sihvonen, J. Structuring servitization-related research. IJOPM 2018, 38, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubic, T.; Jennions, I. Remote monitoring technology and servitised strategies – factors characterising the organisational application. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusek, M. Exploitation, Exploration, or Ambidextrousness—An Analysis of the Necessary Conditions for the Success of Digital Servitisation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, J.; Agarwal, G. Perception of value delivered in digital servitization. Industrial Marketing Management 2021, 99, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioli, V.; Ruggeri, G.; Sala, R.; Pirola, F.; Pezzotta, G. A Methodology for the Design and Engineering of Smart Product Service Systems: An Application in the Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Oghazi, P.; Gebauer, H.; Baines, T. Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm. Journal of Business Research 2019, 104, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-87641-1. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: Ein Handbuch für Visionäre, Spielveränderer und Herausforderer, 1. Auflage; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, New York, 2011; ISBN 978-3-593-39474-9. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnowski, A.; Böhmann, T. Grundlagen service-orientierter Geschäftsmodelle. In Service-orientierte Geschäftsmodelle; Böhmann, T., Warg, M., Weiß, P., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-3-642-41624-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zolnowski, A.; Böhmann, T. Veränderungstreiber service-orientierter Geschäftsmodelle. In Service-orientierte Geschäftsmodelle; Böhmann, T., Warg, M., Weiß, P., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 31–52. ISBN 978-3-642-41624-8. [Google Scholar]

- Service-orientierte Geschäftsmodelle; Böhmann, T. ; Warg, M.; Weiß, P., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-41624-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, B.; Böhmann, T. Data-Driven Business Models - Building the Bridge Between Data and Value. European Conference on Information Systems 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zolnowski, A.; Christiansen, T.; Gudat, J. BUSINESS MODEL TRANSFORMATION PATTERNS OF DATA-DRIVEN INNOVATIONS. Twenty-Fourth European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) 2016.

- TRUMPF. Pay per Part – damit Ihre Kosten zu Ihrer Auslastung passen. Available online: https://www.trumpf.com/de_DE/produkte/services/services-maschinen-systeme-und-laser/pay-per-part/ (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Frank, A.G.; Mendes, G.H.; Ayala, N.F.; Ghezzi, A. Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: A business model innovation perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2019, 141, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Evans, S.; Neely, A.; Greenough, R.; Peppard, J.; Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Braganza, A.; Tiwari, A.; et al. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture 2007, 221, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, A.; Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. The Design of Smart Product-Service Systems (PSSs): An Exploration of Design Characteristics. International Journal of Design 2015, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer, H.; Paiola, M.; Saccani, N.; Rapaccini, M. Digital servitization: Crossing the perspectives of digitization and servitization. Industrial Marketing Management 2021, 93, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.; Schroeder, A.; Kapoor, K.K.; Ziaee Bigdeli, A.; Baines, T. Behind the scenes of digital servitization: Actualising IoT-enabled affordances. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 89, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Kohtamäki, M.; Wincent, J. An agile co-creation process for digital servitization: A micro-service innovation approach. Journal of Business Research 2020, 112, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklyar, A.; Kowalkowski, C.; Tronvoll, B.; Sörhammar, D. Organizing for digital servitization: A service ecosystem perspective. Journal of Business Research 2019, 104, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolagar, M.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D. Ecosystem transformation for digital servitization: A systematic review, integrative framework, and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research 2022, 146, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Vanderstraeten, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Unravelling the internal and external drivers of digital servitization: A dynamic capabilities and contingency perspective on firm strategy. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 89, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal 2018, 39, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as Structure. Journal of Management 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobben, D.; Ooms, W.; Roijakkers, N.; Radziwon, A. Ecosystem types: A systematic review on boundaries and goals. Journal of Business Research 2022, 142, 138–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, L. Standardsätze: Eingrenzung deiner Bachelorarbeit. Available online: https://www.scribbr.de/wissenschaftliches-schreiben/standardsaetze-eingrenzung-der-arbeit/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Moore, J.F. Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition. Harvard Business Review 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Möller, K. Wertschöpfung in Netzwerken. Zugl.: Stuttgart, Univ., Habil.-Schrift, 2006; Vahlen: München, 2006; ISBN 3800633264. [Google Scholar]

- Humbeck, P. Modell zur Analyse und Gestaltung von Business-Ökosystemen für die Entwicklung von Produkt-Service-Systemen im Maschinenund Anlagenbau. Dissertation; Universität Stuttgart, 2022.

- Mayring, P. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Anleitung zu qualitativem Denken, 6., überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Basel, 2016; ISBN 978-3-407-29452-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnek, S.; Krell, C. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Mit Online-Material, 6., überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Basel, 2016; ISBN 978-3-621-28362-5. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Newcomer, K.E., Hatry, H.P., Wholey, J.S., Eds.; Wiley, 2015; pp 492–505, ISBN 9781118893609.

- Helfferich, C. Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, 3. Aufl.; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer, 2022; pp 875–892, ISBN 978-3-658-37985-8.

- Schultze, U.; Avital, M. Designing interviews to generate rich data for information systems research. Information and organization 2011, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M.; Kuß, A. Grundlagen empirischer Forschung; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2021; ISBN 978-3-658-32889-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen, 4. Auflage; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, 2010; ISBN 978-3-531-17238-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R. Qualitative Experteninterviews; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2021; ISBN 978-3-658-30254-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W. Mixed methods. Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction 2009, 23, 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.; Goertz, G. A tale of two cultures: Contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Political analysis 2006, 14, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. ExpertInneninterviews—vielfach erprobt, wenig bedacht: Ein Beitrag zur qualitativen Methodendiskussion. Das Experteninterview: Theorie, Methode, Anwendung 2002, 71–93.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Kleine und mittlere Unternehmen (KMU). Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Unternehmen/Kleine-Unternehmen-Mittlere-Unternehmen/Glossar/kmu.html (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- European Commission. SME definition. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/smes/sme-definition_en?prefLang=de (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse; Springer, 2019, ISBN 3658213078.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).