Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials

2.2. Genomic DNA extraction and Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) analyses

2.3. Sequence analysis of 2xLOX5 CNVs

2.4. Mechanical wounding of leaves

2.5. RNA extraction and expression analyses using qRT-PCR

2.6. Fall armyworm resistance assay

2.7. Quantification of metabolites

2.8. Drought stress test

2.9. Statistical analysis

3. Results

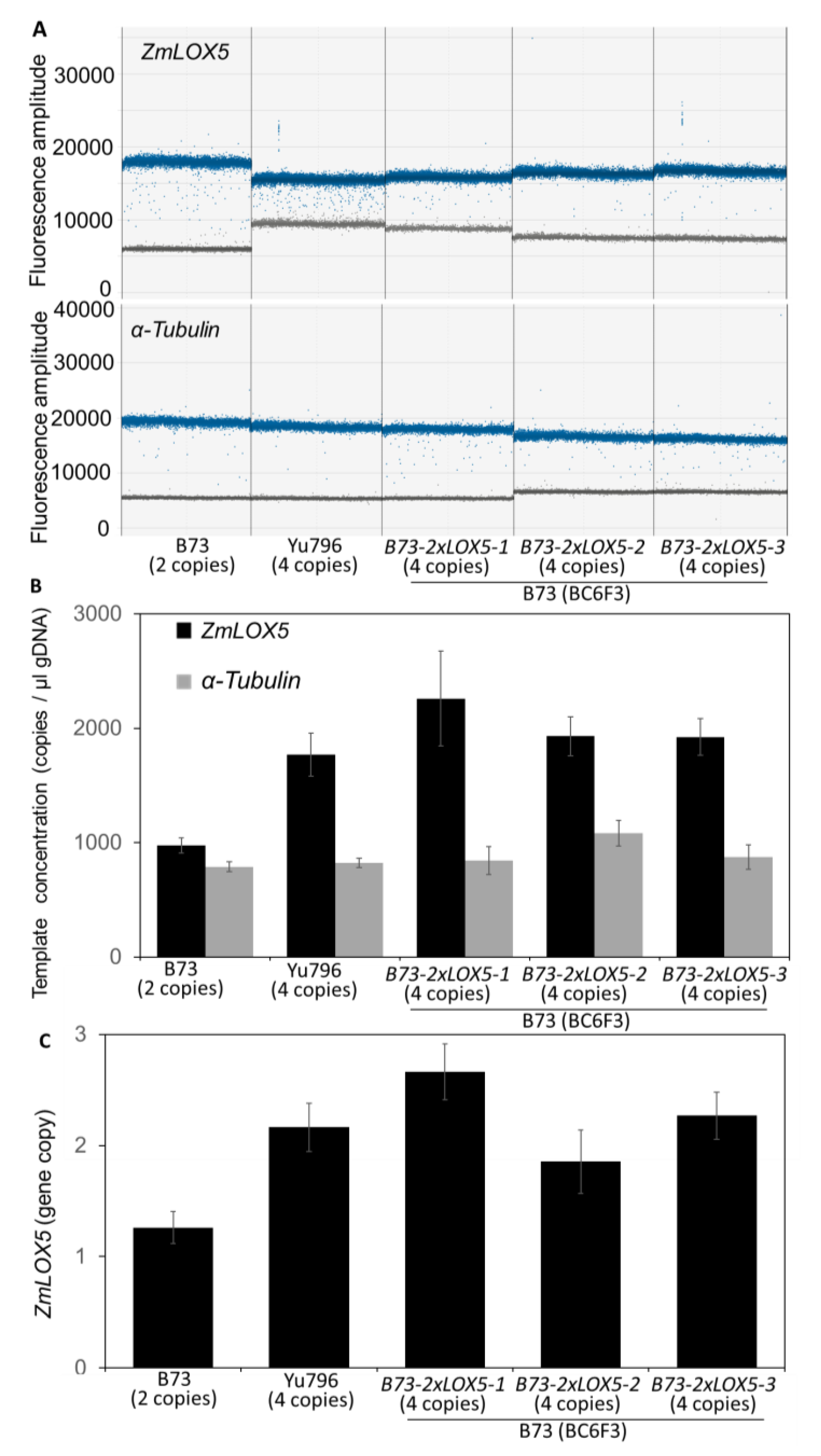

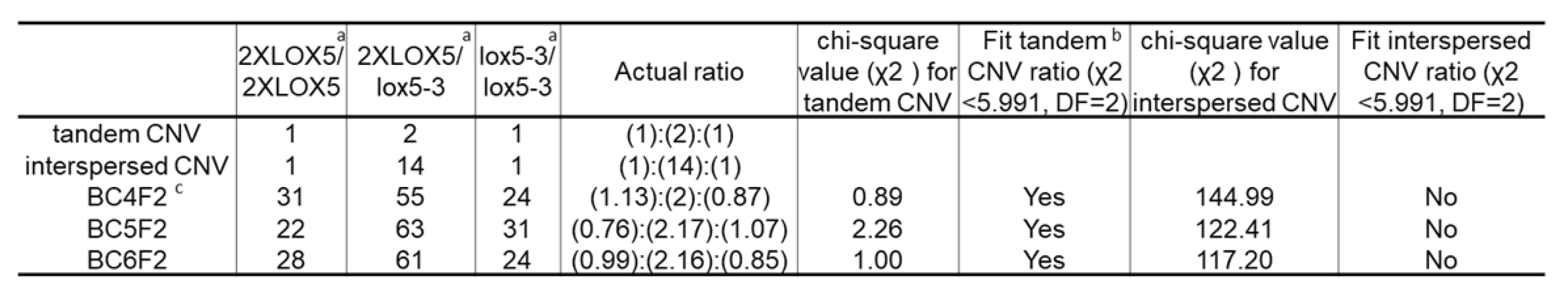

3.1. Introgression of duplicated copy variants of ZmLOX5 from Yu796 into B73

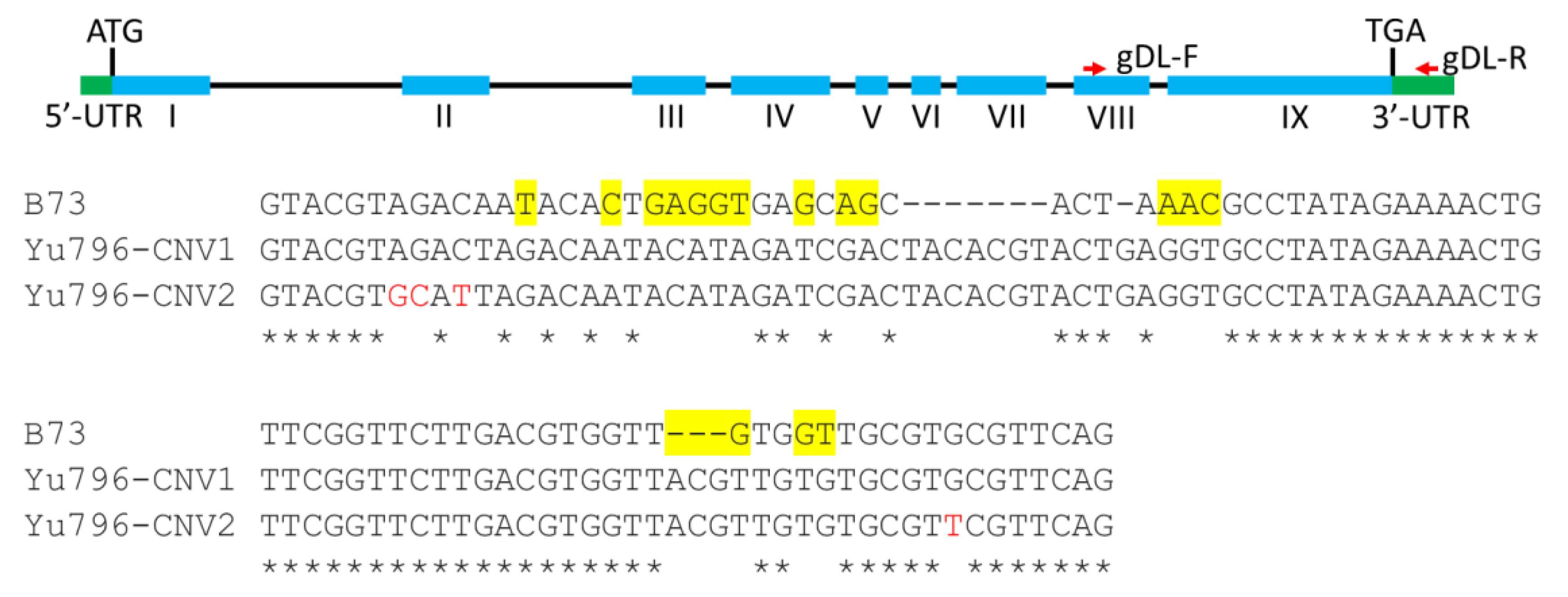

3.2. CNVs of ZmLOX5 are tandemly duplicated and contain multiple SNPs and several indels when compared to the B73-ZmLOX5 locus

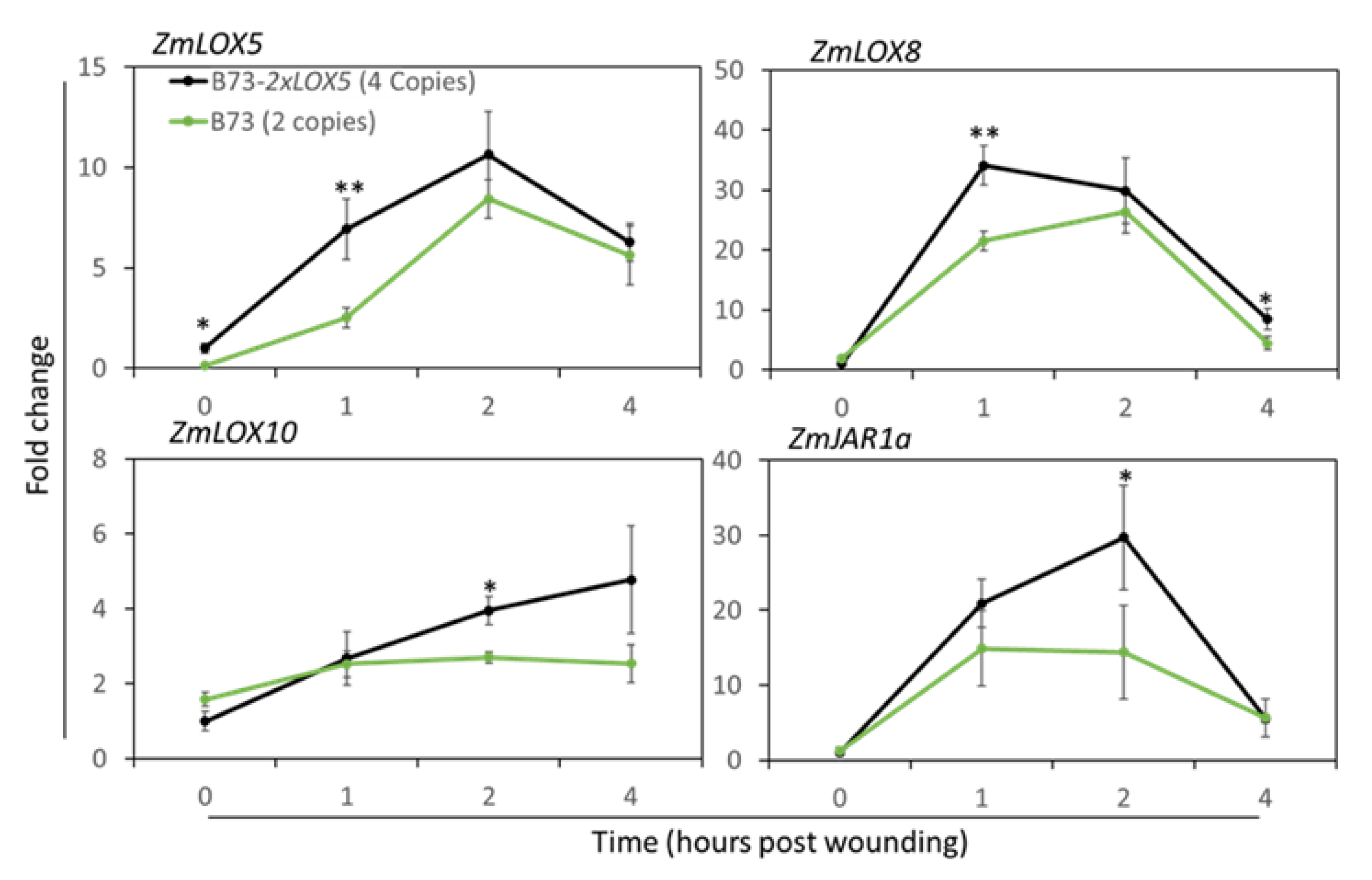

3.3. Duplication of ZmLOX5 leads to the increased expression of ZmLOX5 and other wound-inducible oxylipin biosynthesis genes

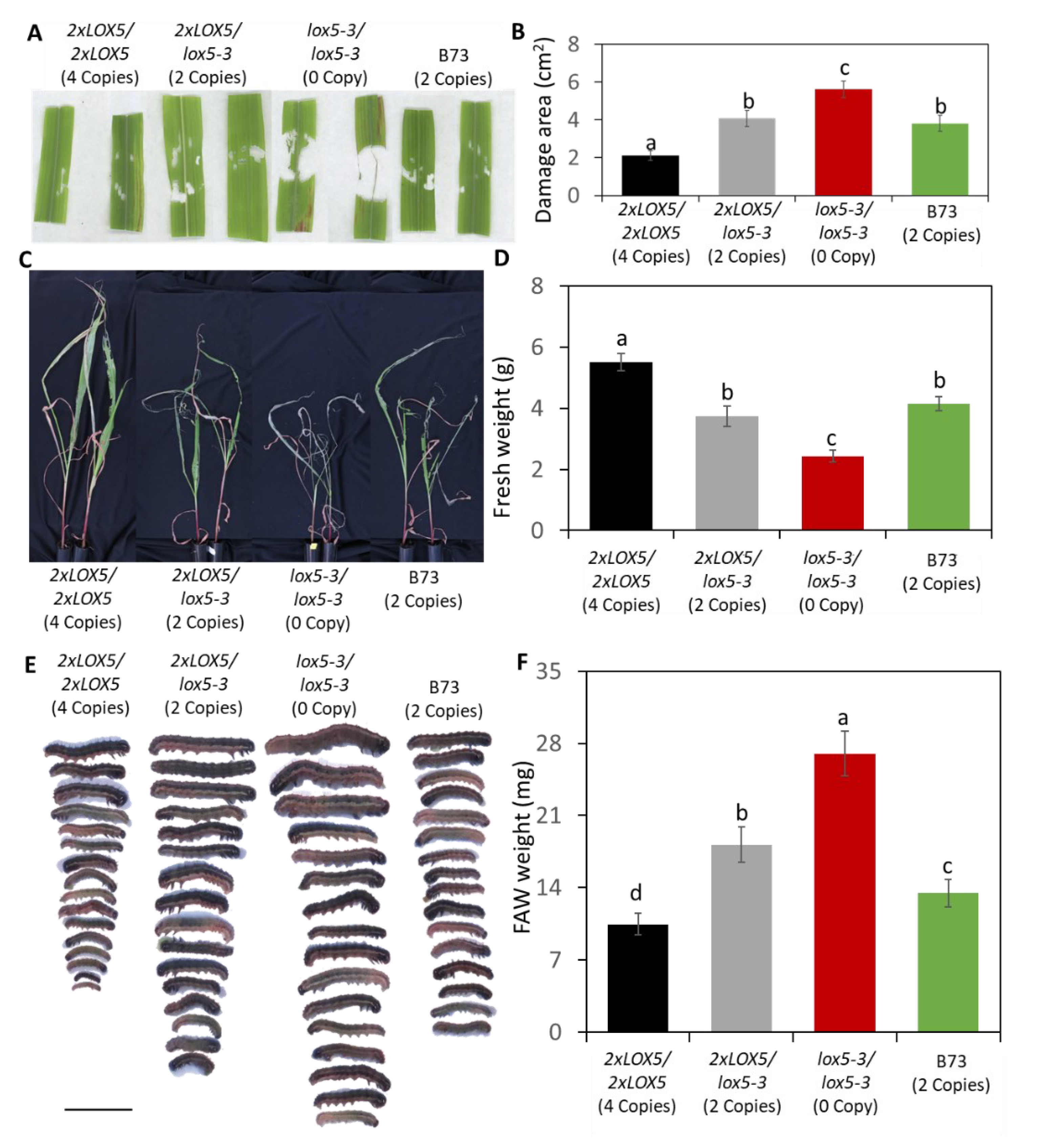

3.4. Duplication of ZmLOX5 conferred enhanced resistance against FAW

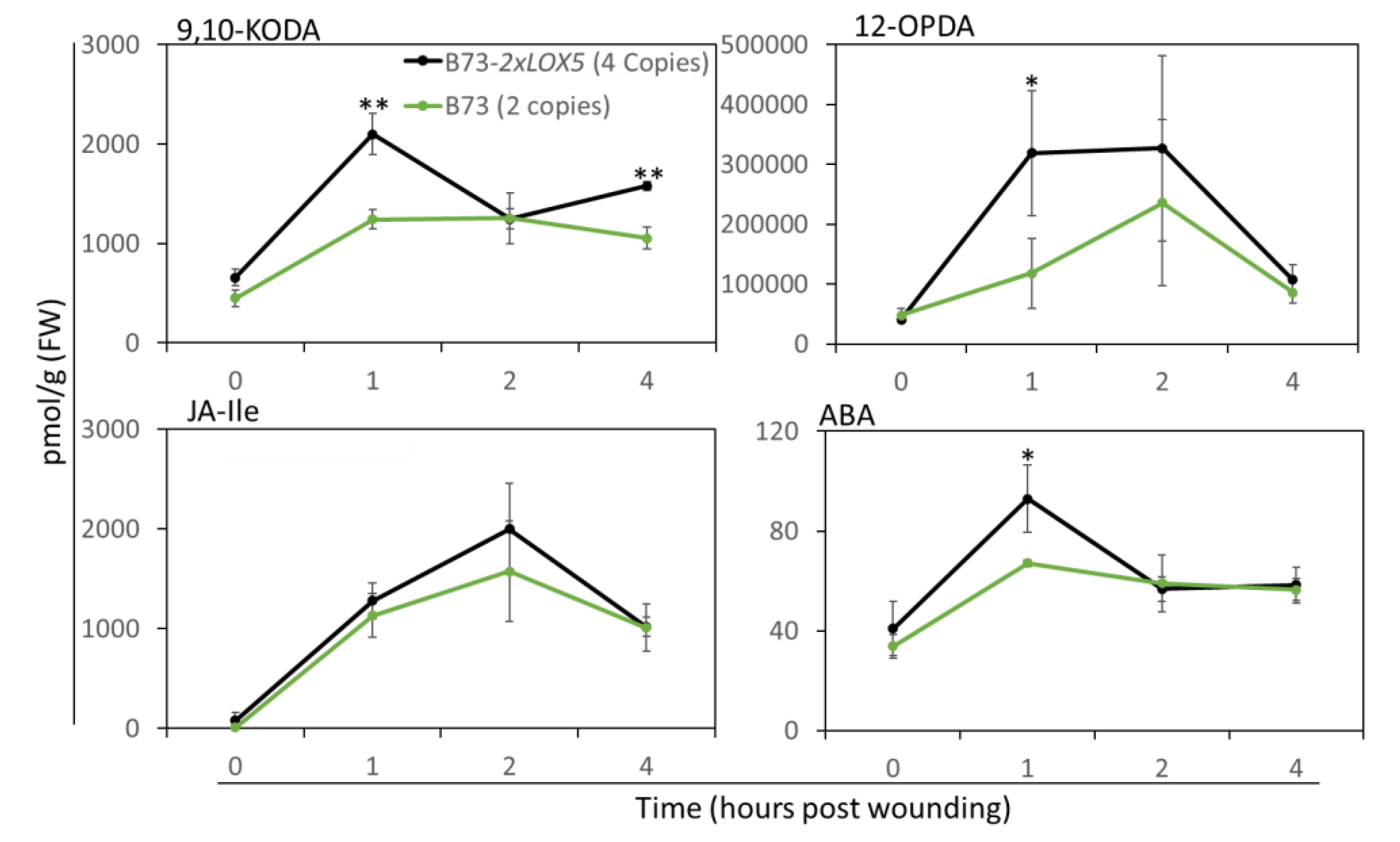

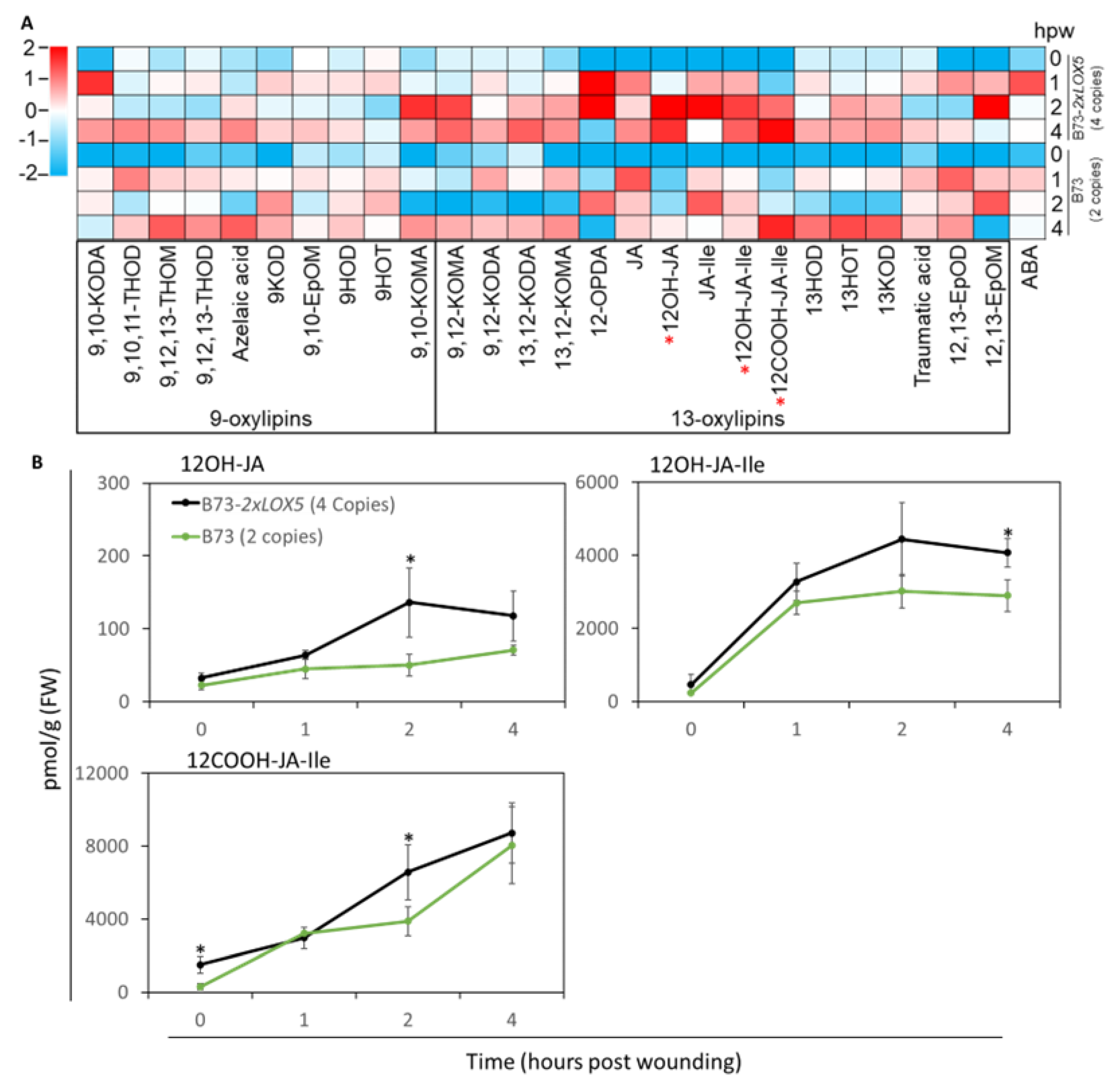

3.5. Duplication of ZmLOX5 promoted wound-induced oxylipin and ABA production

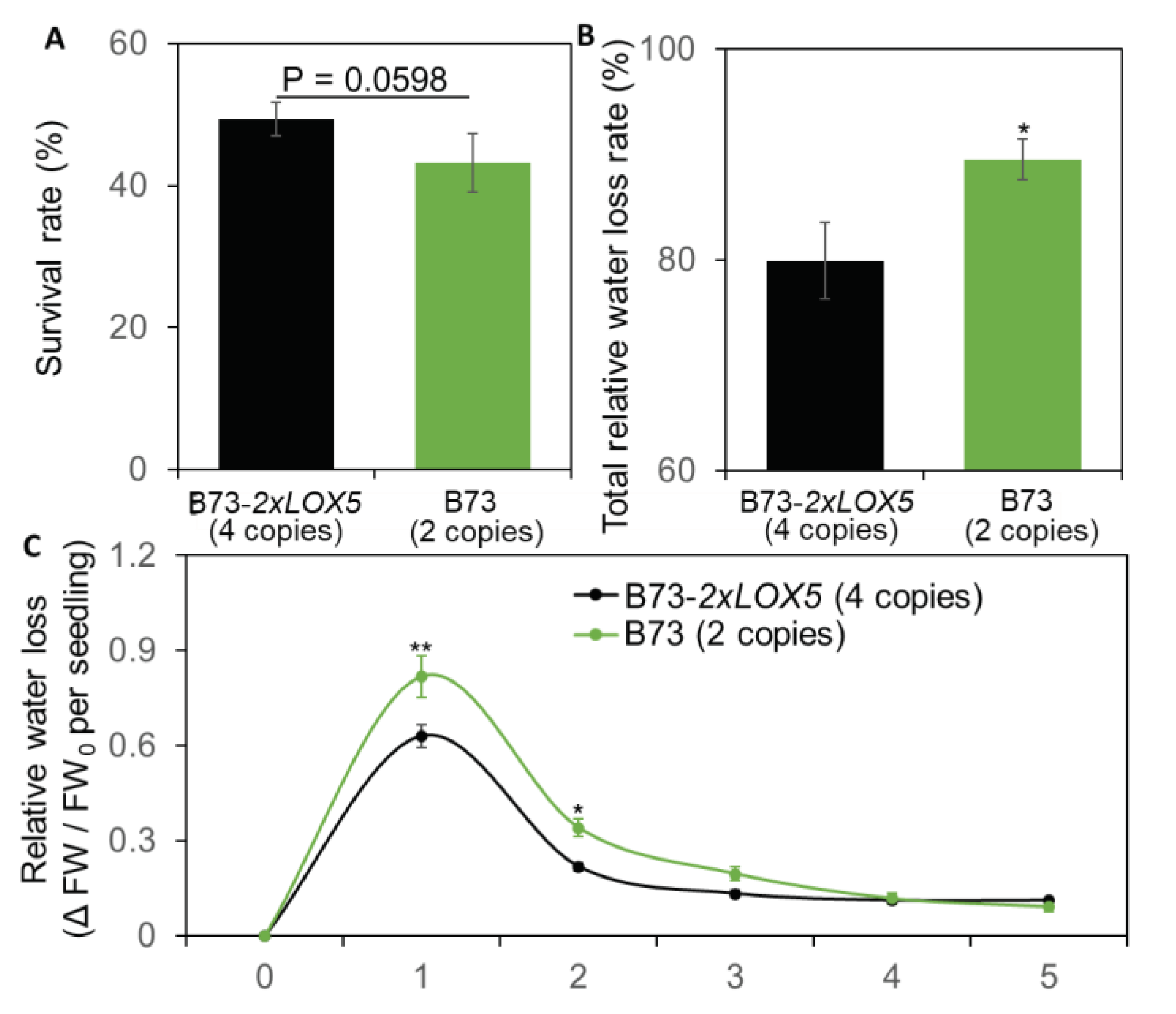

3.6. Duplication of ZmLOX5 promoted drought tolerance

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feldmann, F.; Rieckmann, U.; Winter, S. The spread of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda in Africa—What should be done next? Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2019, 126, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A.; Day, R.K.; Lamontagne-Godwin, J.; Silvestri, S.; Beseh, P.K.; Oppong-Mensah, B.; Phiri, N.A.; Matimelo, M. Tackling fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) outbreak in Africa: an analysis of farmers’ control actions. International Journal of Pest Management 2020, 66, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, K.; Maino, J.L.; Day, R.; Umina, P.A.; Bett, B.; Carnovale, D.; Ekesi, S.; Meagher, R.; Reynolds, O.L. Global crop impacts, yield losses and action thresholds for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): A review. Crop Protection 2021, 145, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, J.; Borah, J.R.; Baudron, F.; Sunderland, T.C.H. Forest Proximity Positively Affects Natural Enemy Mediated Control of Fall Armyworm in Southern Africa. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, M.; Wossen, T.; De Groote, H.; Tefera, T.; Sevgan, S.; Balew, S. Economic impacts of fall armyworm and its management strategies: evidence from southern Ethiopia. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2020, 47, 1473–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makgoba, M.C.; Tshikhudo, P.P.; Nnzeru, L.R.; Makhado, R.A. Impact of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) (J.E. Smith) on small-scale maize farmers and its control strategies in the Limpopo province, South Africa. Jamba (Potchefstroom, South Africa) 2021, 13, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groote, H.; Kimenju, S.C.; Munyua, B.; Palmas, S.; Kassie, M.; Bruce, A. Spread and impact of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith) in maize production areas of Kenya. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2020, 292, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel Timilsena, B.; Niassy, S.; Kimathi, E.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Seidl-Adams, I.; Wamalwa, M.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Ekesi, S.; Hughes, D.P.; Rajotte, E.G. , et al. Potential distribution of fall armyworm in Africa and beyond, considering climate change and irrigation patterns. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Rwomushana, I.; Mugambi, I. Fall armyworm invasion in Sub-Saharan Africa and impacts on community sustainability in the wake of Coronavirus Disease 2019: reviewing the evidence. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2023, 62, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Abrahams, P.; Bateman, M.; Beale, T.; Clottey, V.; Cock, M.; Colmenarez, Y.; Corniani, N.; Early, R.; Godwin, J.; et al. Fall Armyworm: Impacts and Implications for Africa. Outlooks on Pest Management 2017, 28, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConn, M.; Creelman, R.A.; Bell, E.; Mullet, J.E.; Browse, J. Jasmonate is essential for insect defense in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 5473–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, A.J.; Howe, G.A. The wound hormone jasmonate. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staswick, P.E.; Su, W.; Howell, S.H. Methyl jasmonate inhibition of root growth and induction of a leaf protein are decreased in an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 6837–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, P.; Du, L.; Poovaiah, B. Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent AtSR1/CAMTA3 Plays Critical Roles in Balancing Plant Growth and Immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, P.; Borrego, E.; Park, Y.-S.; Gorman, Z.; Huang, P.-C.; Tolley, J.; Christensen, S.A.; Blanford, J.; Kilaru, A.; Meeley, R., et al. 9,10-KODA, an α-ketol produced by the tonoplast-localized 9-lipoxygenase ZmLOX5, plays a signaling role in maize defense against insect herbivory. Molecular Plant 2023, 10.1016/j.molp.2023.07.003, doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.07.003. [CrossRef]

- Berg-Falloure, K.M.; Kolomiets, M.V. Ketols Emerge as Potent Oxylipin Signals Regulating Diverse Physiological Processes in Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Aleman, G.H.; Jander, G. Maize defense against insect herbivory: A novel role for 9-LOX-derived oxylipins. Molecular Plant 2023, 16, 1484–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-S.; Kunze, S.; Ni, X.; Feussner, I.; Kolomiets, M.V. Comparative molecular and biochemical characterization of segmentally duplicated 9-lipoxygenase genes ZmLOX4 and ZmLOX5 of maize. Planta 2010, 231, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Borrego, E.J.; Gorman, Z.; Huang, P.C.; Kolomiets, M.V. Relative contribution of LOX10, green leaf volatiles and JA to wound-induced local and systemic oxylipin and hormone signature in Zea mays (maize). Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, N.M.; Ying, K.; Fu, Y.; Ji, T.; Yeh, C.-T.; Jia, Y.; Wu, W.; Richmond, T.; Kitzman, J.; Rosenbaum, H. , et al. Maize Inbreds Exhibit High Levels of Copy Number Variation (CNV) and Presence/Absence Variation (PAV) in Genome Content. PLOS Genetics 2009, 5, e1000734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadian, A.; Yuan, Y.; Bayer, P.E.; Petereit, J.; Severn-Ellis, A.; Tirnaz, S.; Patel, D.; Edwards, D.; Batley, J. Copy Number Variation among Resistance Genes Analogues in Brassica napus. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żmieńko, A.; Samelak, A.; Kozłowski, P.; Figlerowicz, M. Copy number polymorphism in plant genomes. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 2014, 127, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Fuente, G.N.; Murray, S.C.; Isakeit, T.; Park, Y.-S.; Yan, Y.; Warburton, M.L.; Kolomiets, M.V. Characterization of Genetic Diversity and Linkage Disequilibrium of ZmLOX4 and ZmLOX5 Loci in Maize. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e53973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.M.; Dudley, Q.M.; Patron, N.J. Measurement of Transgene Copy Number in Plants Using Droplet Digital PCR. Bio Protoc 2021, 11, e4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.D.; Usher, C.L.; McCarroll, S.A. Analyzing Copy Number Variation with Droplet Digital PCR. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1768, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Joyce, P.A. Application of droplet digital PCR to determine copy number of endogenous genes and transgenes in sugarcane. Plant Cell Reports 2017, 36, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.-D.; Borrego, E.J.; Kenerley, C.M.; Kolomiets, M.V. Oxylipins Other Than Jasmonic Acid Are Xylem-Resident Signals Regulating Systemic Resistance Induced by <em>Trichoderma virens</em> in Maize. The Plant Cell 2020, 32, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindson, B.J.; Ness, K.D.; Masquelier, D.A.; Belgrader, P.; Heredia, N.J.; Makarewicz, A.J.; Bright, I.J.; Lucero, M.Y.; Hiddessen, A.L.; Legler, T.C.; et al. High-Throughput Droplet Digital PCR System for Absolute Quantitation of DNA Copy Number. Analytical Chemistry 2011, 83, 8604–8610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotke, L.; Lau, B.T.; Rumma, R.T.; Ji, H.P. High Sensitivity Detection and Quantitation of DNA Copy Number and Single Nucleotide Variants with Single Color Droplet Digital PCR. Analytical Chemistry 2014, 86, 2618–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, C.; Li, X.; Xie, C. Genome Editing Enables Next-Generation Hybrid Seed Production Technology. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, C.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Xie, C. Pollen self-elimination CRISPR-Cas genome editing prevents transgenic pollen dispersal in maize. Plant communications 2023, 4, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwobi, A.; Gerdes, L.; Busch, U.; Pecoraro, S. Droplet digital PCR for routine analysis of genetically modified foods (GMO) – A comparison with real-time quantitative PCR. Food Control 2016, 69, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.M.; Branco, J.A. A Statistical Model to Explain the Mendel–Fisher Controversy. Statistical Science 2010, 25, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, Z.N.; Purugganan, M.D. Copy Number Variation in Domestication. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunde, C.; Kimberlin, A.; Leiboff, S.; Koo, A.J.; Hake, S. Tasselseed5 overexpresses a wound-inducible enzyme, ZmCYP94B1, that affects jasmonate catabolism, sex determination, and plant architecture in maize. Communications Biology 2019, 2, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.-C.; Grunseich, J.M.; Berg-Falloure, K.M.; Tolley, J.P.; Koiwa, H.; Bernal, J.S.; Kolomiets, M.V. Maize OPR2 and LOX10 Mediate Defense against Fall Armyworm and Western Corn Rootworm by Tissue-Specific Regulation of Jasmonic Acid and Ketol Metabolism. Genes 2023, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Satoh, R.; Maruyama, K.; Parvez, M.M.; Seki, M.; Hiratsu, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AREB1 Is a Transcription Activator of Novel ABRE-Dependent ABA Signaling That Enhances Drought Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis The Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3470-3488, doi:10.1105/tpc.105.035659. [CrossRef]

- Leckie, C.P.; McAinsh, M.R.; Allen, G.J.; Sanders, D.; Hetherington, A.M. Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure mediated by cyclic ADP-ribose. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 15837–15842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Shi, M.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, H.; Ou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Day, B.; Miao, C.; Jiang, K. Light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis is negatively regulated by chloroplast-originated OPDA signaling. Current Biology 2023, 33, 1071–1081.e1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, J.M.; Cooper, G.M.; Donahue, W.F.; Hayden, H.S.; Sampas, N.; Graves, T.; Hansen, N.; Teague, B.; Alkan, C.; Antonacci, F.; et al. Mapping and sequencing of structural variation from eight human genomes. Nature 2008, 453, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.E.; Lee, T.G.; Guo, X.; Melito, S.; Wang, K.; Bayless, A.M.; Wang, J.; Hughes, T.J.; Willis, D.K.; Clemente, T.E.; et al. Copy Number Variation of Multiple Genes at Rhg1 Mediates Nematode Resistance in Soybean. Science 2012, 338, 1206–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Poovaiah, B.W. Interplay between Ca2+/Calmodulin-Mediated Signaling and AtSR1/CAMTA3 during Increased Temperature Resulting in Compromised Immune Response in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, F.; Skirycz, A.; Simoni, L.; Castorina, G.; de Souza, L.P.; Fernie, A.R.; Alseekh, S.; Giavalisco, P.; Conti, L.; Tonelli, C.; et al. The AtMYB60 transcription factor regulates stomatal opening by modulating oxylipin synthesis in guard cells. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, E.; Osmani, A.A.; Ahmadi, S.H.; Ogawa, S.; Takagi, K.; Yokoyama, M.; Ban, T. KODA, an α-ketol derivative of linolenic acid provides wide recovery ability of wheat against various abiotic stresses. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2016, 7, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashov, F.A. Gene duplication as a mechanism of genomic adaptation to a changing environment. Proceedings. Biological sciences 2012, 279, 5048–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingen, L.U.; Münster, T.; Faigl, W.; Deleu, W.; Sommer, H.; Saedler, H.; Theißen, G. Molecular genetic basis of pod corn (Tunicate maize). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 7115–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, J.; Lithio, A.; Dash, S.; Weber, D.F.; Wise, R.; Nettleton, D.; Peterson, T. Genes and Small RNA Transcripts Exhibit Dosage-Dependent Expression Pattern in Maize Copy-Number Alterations. Genetics 2016, 203, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, L.G.; Guimarães, C.T.; Kirst, M.; Albert, P.S.; Birchler, J.A.; Bradbury, P.J.; Buckler, E.S.; Coluccio, A.E.; Danilova, T.V.; Kudrna, D.; et al. Aluminum tolerance in maize is associated with higher MATE1 gene copy number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 5241–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, A.C.M.; McClymont, S.A.; Soliman, S.S.M.; Raizada, M.N. The effect of altered dosage of a mutant allele of Teosinte branched 1 (tb1-ref) on the root system of modern maize. BMC Genetics 2014, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Shi, J.; Sun, C.; Gong, H.; Fan, X.; Qiu, F.; Huang, X.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, X.; Yuan, N.; et al. Gene duplication confers enhanced expression of 27-kDa γ-zein for endosperm modification in quality protein maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 4964–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ren, J.; Peng, Z.; Umana, A.A.; Le, H.; Danilova, T.; Fu, J.; Wang, H.; Robertson, A.; Hulbert, S.H.; et al. Analysis of Extreme Phenotype Bulk Copy Number Variation (XP-CNV) Identified the Association of rp1 with Resistance to Goss's Wilt of Maize. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingen, L.U.; Münster, T.; Faigl, W.; Deleu, W.; Sommer, H.; Saedler, H.; Theißen, G. Molecular genetic basis of pod corn Tunicate maize). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 7115–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).