1. Introduction

The sustainability of suburban development around Budapest, Hungary, and the effects of suburbs on the sustainability of Budapest have recently been intensely debated in professional circles and public media in Hungary. Most of the debates concentrate on the negative consequences of commuting and sprawl and the insufficiency of infrastructure in the spreading urbanized area.

This paper does not endeavor to delineate and analyze the sustainability situation of suburban Budapest. The territory in question is too large and complex, and the question of suburban sustainability is multifaceted, making such an attempt impossible and futile. Instead, we shall focus on a particular town, Törökbálint, with high resolution, based on primary data using one specific theoretical framework, the Smart Growth Theory, and center on a well-defined set of aspects of sustainability.

An in-depth analysis of one town allows for a comprehensible understanding of local nuances, specific context, and details, providing depth, richer insights, and a better understanding of the delicate patterns, connections, and underlying mechanisms. On the contrary, conclusions drawn from the specific locality may only be cautiously generalized. With this method, however, fine details of the phenomena and processes that otherwise would be lost in a coarser, less comprehensive examination may be detected and scrutinized.

2. Sustainability of suburbs

Concerns about the sustainability of suburbs appeared relatively recently. From early antiquity, those urban dwellers who had a residence outside the city valued having a place in the country to enjoy the benefits of both the urban and rural surroundings, services, and joys, and the emphasis was placed on the pleasures surrounding areas offered to the urbanites, or it served as a refuge from urban miseries and pandemics [

1] (pp. 483-487). For long decades after the start of massive suburbanization in the latter half of the 19

th century, living in the less dense areas in larger and cozy homes more distant from the noisy and polluted central regions was seen as a democratization of privileges the aristocrats had had [

2]. Indeed, the most important motives of suburbanites did not include the proximity to nature or the desire for a garden or yard but yearning for a ‘cleaner, healthier neighborhood [

1] (p. 487). In the second half of the 19

th and the first half of the 20

th century, suburbanization seemed a feasible, necessary, and advisable measure to ease the malaise and miseries massive urbanization brought about in significant cities [

1,

2].

The first significant criticism of suburbs targeted the bourgeois boredom and blandness [

3] and aesthetical uniformity, monotony, and ugliness [

1], where people moved for cheap and spacious housing, good schools, and convenient shopping [

4]. The chaotic urban sprawl, especially in larger cities, was considered incomprehensible, where endless rows of subdivisions eradicated nature, one of the prime reasons people moved to suburbs [

2]. With the advent of ubiquitous car usage and the appearance of lower-density residential areas in the suburbs, neighborhoods disappeared as organizing factors of community and social integration. Scientific appreciation of such developments suddenly turned negative as they represented the antithesis of cities [

1] (pp.509-511). The automobile was the culprit that converted not just the appealing suburbs into dreadful ones but also transformed and eradicated traditional cities into grotesque, Los Angeles-type mazes [

2,

5]. More fundamental environmental concerns started to appear in the 1960s as negative consequences of increased traffic, shrinking green areas, rising soil and water pollution, and disappearing flora and fauna were realized, together with the appreciation of green regions and parks [

3,

6].

Nonetheless, most critical approaches evaded aspects of sustainability. They focused in their assessment on social homogeneity, exclusion and social isolation, conformity, alienation and loss of community, female oppression, and excessive mobility. They construed massive suburbanization as an expression of greedy capitalism until recently [

7] (pp. 291-320).

New scientific scrutiny regarding the connection between the natural and urban environment arose in the late 1980s with the strengthening of green social movements. The distinction between ecocentric and anthropocentric sets of attitudes towards the environment was developed [

8,

9] and applied to green areas [

10] and to urban planning [

11] and then turned into New Ecological and Human Exemptionalism paradigms, respectively [

12]. In his highly influential book [

13], Glaeser argues that living in cities is less harmful to the environment than in suburbs: living in sparsely populated areas requires more traveling and commuting, and residing in large, detached houses consumes more energy and takes up more area, although he gives a thorough account on why people of different social strata have yearned for living in the suburbs and on the contradictions harsh environmental policies would evoke.

In recent scientific examinations, several frameworks to incorporate all the environmental, social, and economic factors have been elaborated to study sustainability in the suburbs. Based on ecocentric principles, the

Urban Ecology Framework zeroed in on the interactions between human activities and the natural environment within the context of built-up areas [

14,

15,

16]. Regarding suburbs, it focuses on how the sprawl of urbanized territories, the accompanying expansions of road infrastructure and other amenities, and the expansion of human activities impact the natural environment and the ecosystems [

17,

18]. This approach emphasizes the limits to human progress and economic growth. As a recent shift in it, the newly developed

Urban Political Ecology paradigm attempts to evade the rupture between ecocentrism and anthropocentrism by considering urban and natural not separate but intertwined and indivisible and scrutinizes suburbanization as urbanization of nature, and regards urban and suburban as part of the same ecosystem rather than distinct in general and one as more sustainable

per se than the other in particular [

19] (pp. 151-153).

Founded on anthropocentric principles but with sensitivity to ecological arguments,

Resilience Theory generally focuses on exploring the urban systems to absorb shocks, their capacity to adapt to changes and disturbances, and to maintain functionality and identity [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. When applied to suburbs, it focuses on how suburban areas may be adjusted to changing societal and economic circumstances [

25,

26], disasters [

27,

28], climate change [

29,

30,

31], and warfare [

32,

33].

Approaches belonging to the Smart Growth Framework and New Urbanism are also based on anthropocentric principles but emphasize compact, mixed-use development focusing on public transit, walkability, and community development to contain urban sprawl [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Analyses in this framework had essentially concentrated on suburbs and only later applied their tools to inner urban areas [

38,

39] or inner suburbs [

40,

41]. They emphasize reducing urban sprawl, increasing the share of public transportation while reducing car usage, and creating walkable, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods. They promote densification around public transportation hubs and the development of compact, multifunctional areas with integrated residential, recreational, entertainment, and commercial spaces. Besides the physical aspects, they heavily emphasize community development, social cohesion, and mitigating environmental impacts to foster sustainability in suburban living [

42,

43].

In this paper, we use the Smart Growth framework to analyze the situation of suburban sustainability in the inner Budapest Metropolitan Region (Hungary) in precision. Numerous analyses center on the planning angle: how sustainability ideas are implemented [

44]. As social scientists, we are focusing on the attitudes and behaviors of residents that underpin, transform, or prevent such interventions, forming their social background. We therefore analyze three C aspects, that is, compactness, commuting, and community, in detail. We chose this framework because it touches upon Hungary's fiercest policy and urban development debates with relevance to a broader international audience. In the discussion, however, we shall reflect on other frameworks, too, especially the Urban Political Ecology paradigm.

3. Suburban growth in the Budapest Metropolitan Region

The situation and tendencies of suburbanization and urban sprawl around Budapest have been thoroughly described, studied, and analyzed in the scientific literature of late, in general [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50], or concerning specific aspects, such as spatial decentralization [

51], socio-economic segregation [

52], power relations [

53], regional planning [

54], suburban creativity [

55,

56], suburban communities [

57,

58], suburban peripheries [

59], post-Fordist polycentric spatial structure [

60], effects of COVID [

61], and inner-peripheral [

62] and ecological [

63,

64] sustainability. Therefore, only the most essential characteristics necessary to understand the later analyses will be summarized based on recent accounts [

50,

56].

3.1. General patterns of urban sprawl

Urban sprawl in general, and suburbanization in particular, have been long-spanning spatial processes affecting regions around Budapest since the last third of the 19

th century, where first migration from the countryside to the less preferable, especially eastern, outskirts parallel to the relocation of industrial and other economic activities to the proximity of the same areas dominated; that was amended to a lesser extent in the first decades of the 20

th century by outward migration of the better-off social strata, especially to the western, hilly outer areas. Under slightly different circumstances in the interwar period, the same basic pattern prevailed with an accelerated suburbanization that by then involved broader layers of the middle strata, covering enlarging areas, having made accessible by the rapid expansion of the transit network, especially tram and train lines [

50,

65].

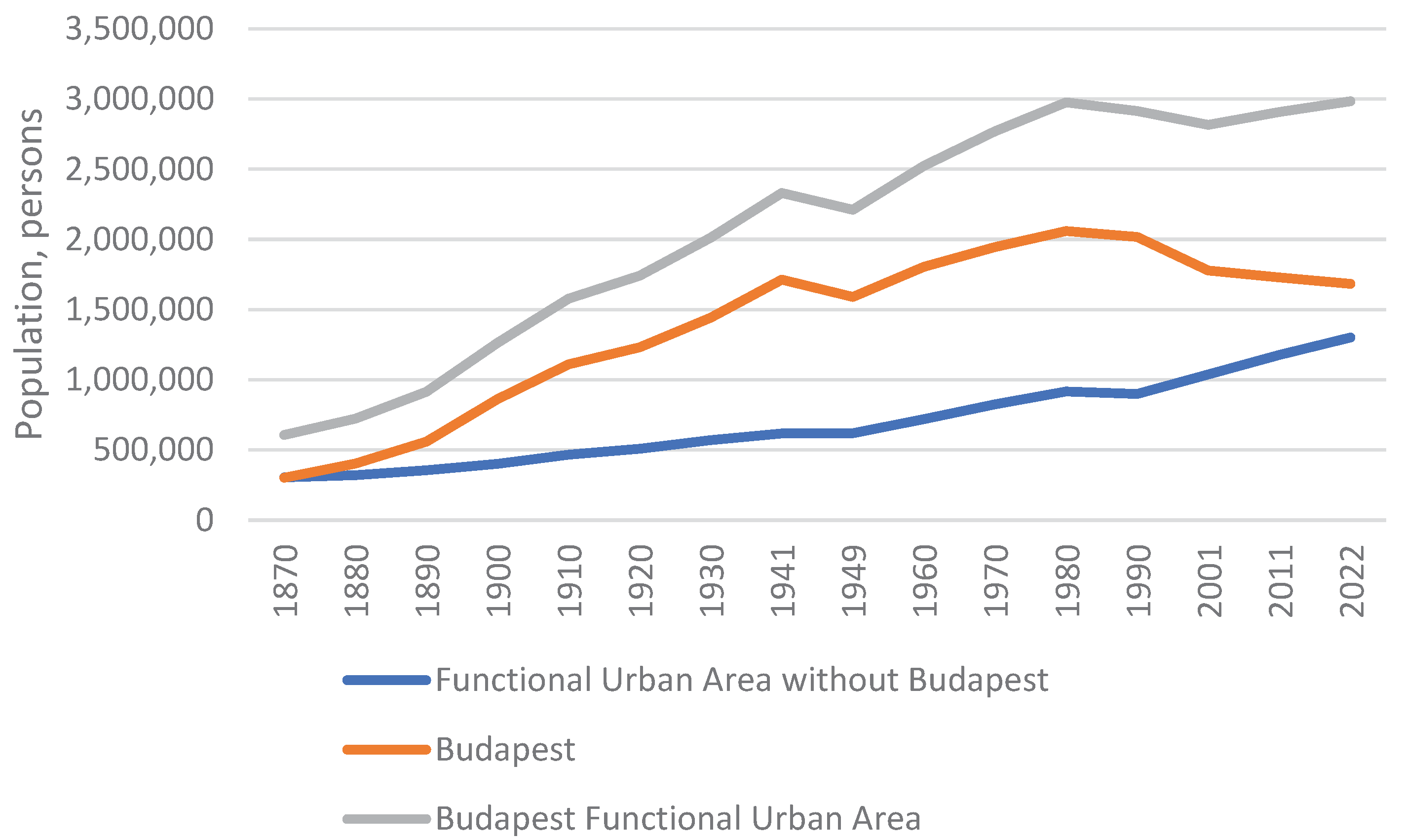

The socialist period between 1948 and 1989, on the one hand, retained some fundamental characteristics of the development but brought about radical changes. Budapest remained monocentric throughout the period and grew in population (see

Figure 1). Besides, through the extension of the city limits in 1950, most importantly, suburbs were incorporated and lost their potential to become viable subcenters due to the socialist urban policies and scarcity of resources. Moreover, suburban towns and villages outside the official city limits were intentionally kept underdeveloped, needing more essential services and amenities. Urban sprawl and suburbanization affected predominantly the outer areas within the city limits. At the same time, it had an impact of provisional suburbanization – that is, weekend cottages and garden plots – outside of it. All the above processes resulted in a poorly serviced, low-status, relatively homogenous suburban belt adjacent to the city limits. Only those who could not move more inward migrated there [

56] (pp. 202-203).

The transition to a market economy in 1989 was gradual but, in essence, drastically changed the scene. Budapest has continued to attract a significant number of migrants from the countryside and abroad, but the momentum of growth swiftly shifted to the outer areas (see

Figure 1). With the abrupt evaporation of centralized control over settlements, the highly autonomous local municipalities started rapidly modernizing their infrastructure and services. On the other side of the city limits, deficiencies, economic problems, and growing social polarization pushed vast portions of the population towards the opening peripheries, resulting in a ‘suburban revolution’ [

56] (p. 204). Following earlier patterns, the better-off migrated to the western, northern, and northeastern, hilly, suburban areas, while the poorer strata chose the southern and southeastern, geographically flat outskirts. Municipalities and private developers opened huge residential plots, usually on greenfields, to create revenues and purchase power for more local development and services. As a result, a large number of affluential families with numerous children appeared in towns and villages with initially homogeneous, low-status, aging populations in the more prestigious areas, creating one particular set of issues [

58], while the arrival of the urban poor created tensions in disadvantageous ones [

66].

The above changes coincided with the post-Fordist transition of the economy, tangible from the end of the 1990s. As a result, a more comprehensive range of economic and commercial activities appeared in some select territories, turning the previously predominantly residential towns into subcenters with a high demand for employment, changing lifestyles, and townscape [

56] (pp. 205-206). Other towns and villages, even close physical proximity to the bourgeoning subcenters, notwithstanding, still need to be developed, residential in character, with deficient services, where employees almost exclusively rely on commuting to the capital or the new subcenters [

50].

3.2. Area of the case study

Törökbálint, a town with an autonomous municipality with urban rights, is situated near the core of the Hungarian capital; it lies 12.5 kilometers southwest of the center of Budapest, where it shares a shared city limit. It is well connected and easily accessible by road – all the M0, M1, and M7 major motorways run through, or close to, the town, though they affect the urbanized areas of the town geographically less. Public transportation is well-developed; it has a train stop, but buses are the primary means of transportation. Frequent bus services connect the town with the nearest underground train terminus, 8.7 kilometers or fifteen minutes away. It is one of the three towns that form the most developed subcenter in the inner Budapest Metropolitan Area, with important office, commercial, and logistic functions. The neighboring town, Budaörs, is home to one of Hungary's substantial commercial concentrations, based on residents' high purchasing power in nearby towns and districts of Budapest. However, Törökbálint also hosts some major shopping facilities in its outer areas, along the M0 and M1 motorways, serving a meaningful clientele from a vast region.

The town's total area is 29.5 square kilometers, of which 8.9 square kilometers form the urbanized area. Its population of 14,741 (end of 2022) resides in 5,244 dwelling units. The housing stock consists almost exclusively of detached houses, complemented by some semi-detached and terraced houses. The average population density is 1,656 persons per square kilometer, which is between the average in the United States (1,050) and in Western Europe (2,400) [

67].

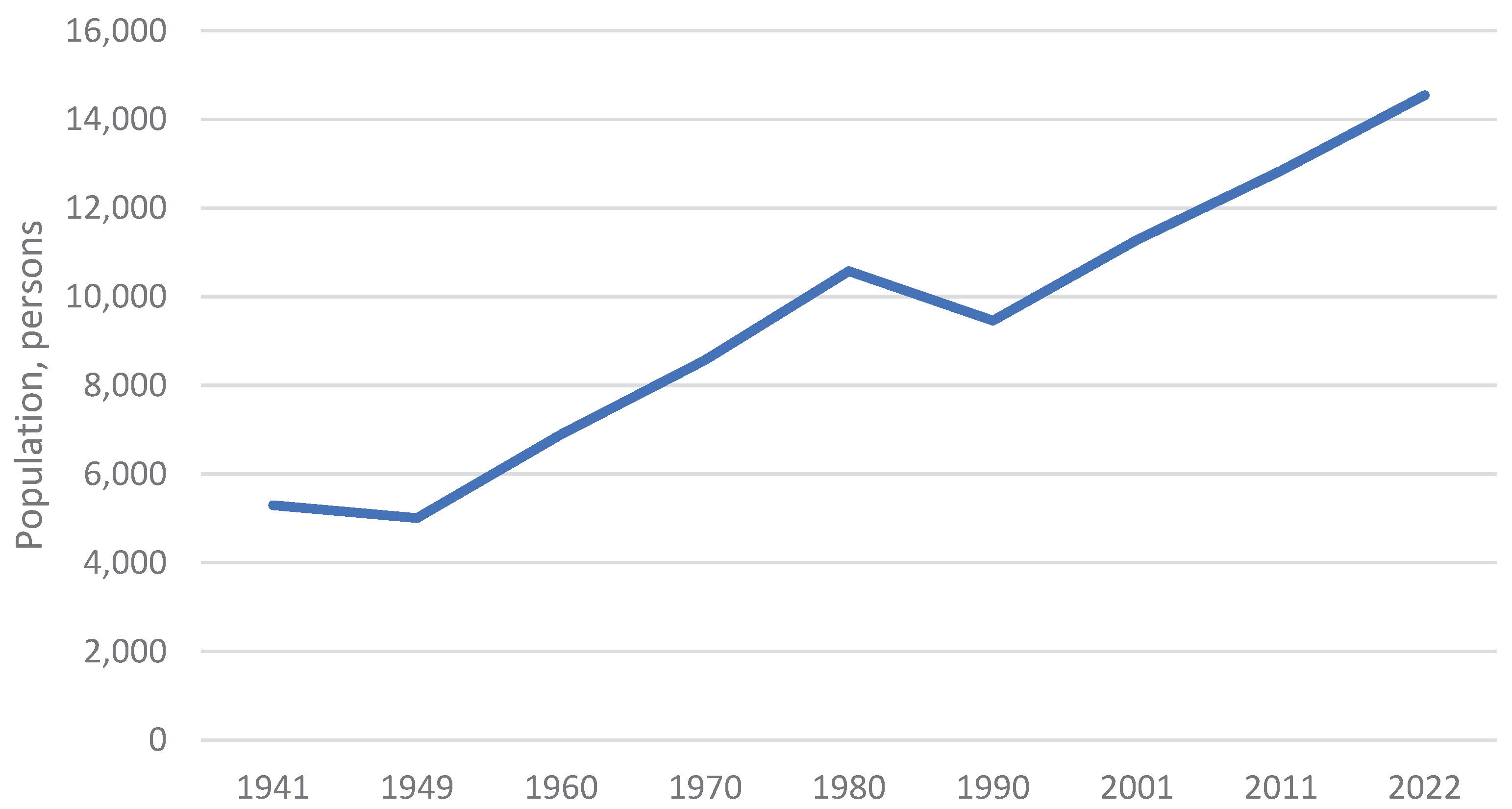

Its population constantly increases (see

Figure 2); it grew by 50% between 1990 and 2022. Whereas most migrants were lower-skilled workers in the 1960s and 1970s, nowadays, the higher-status migrants form the majority [

58]. Consequently, the town is spatially and socially heterogeneous, with substantial gentrification in the traditional, rural core areas and complex social development in the neighborhoods constructed in the 1960s and 1970s. Geographically and aesthetically segregated, its northeastern neighborhood, developed in the mid-1990s, is regarded as one of the most prestigious ones in Hungary.

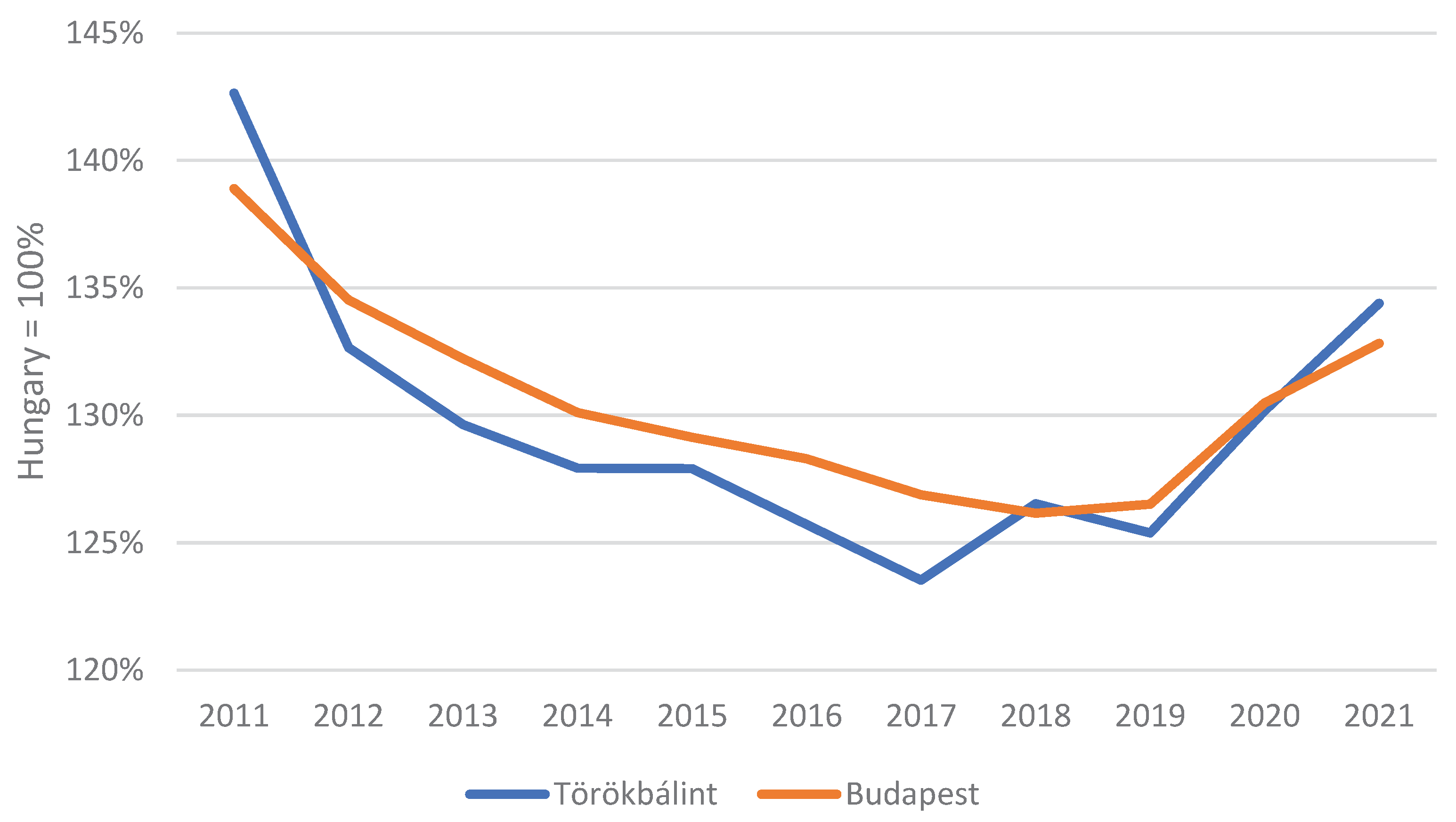

The town has one of the most educated populations outside of Budapest in Hungary, with a high average income (see

Figure 3). The average age is relatively young due to the influx of young families with numerous children. The level of unemployment is low, and the activity rate is high. Historically, the local identity enrooted in periods before the massive suburban influx is distinct and robust, based on the local traditional rural community, but inclusively adapting to the newcomers’ attitudes and values [

56].

The historic center lies on the southern edge of the town, whereas major residential areas are to the north and the northeast. Large and loosely developed outskirts in the south and southeast are home to a few residents with poor services and accessibility – such areas used to be allotment gardens sprung up during the socialist epoch [

56].

Amenities and public services are of good quality, with renowned educational and sports facilities. On the other hand, its central streets lack urban services, shops, and entertainment facilities. Most of the shopping activities are performed in nearby shopping malls and at major food chains.

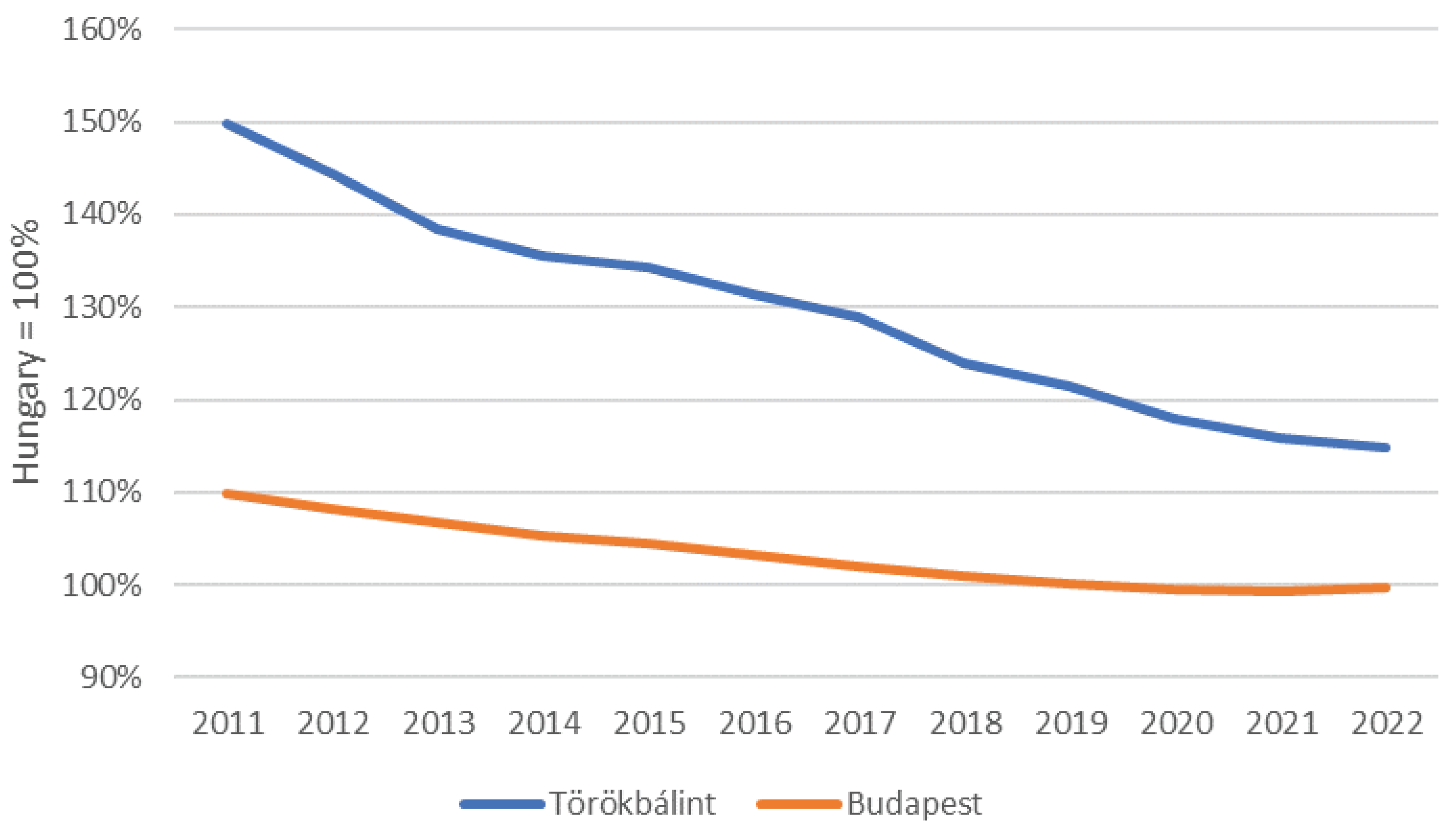

An essential feature in sustainability discourses, the actual characteristics of car penetration show a somewhat unexpected picture. Though car penetration may be measured with rather considerable uncertainty in some specific locations in Hungary because a great deal of higher rank employees may use company cars for private purposes that are registered to the location of the firm; in addition, the increasing number of children that is a tangible phenomenon may also modify the result; the tendency is unequivocal: car penetration is decreasing when compared to the significant growth in the national average (see

Figure 4). Car penetration is slightly growing in sheer numbers in Törökbálint, from 448 in 2011 to 489 in 2022, while it soared from 299 in 2011 to 426 in 2022 in Hungary – all these numbers are, however, low compared to most European Union countries.

4. Materials and Methods

We used primary databases taken in one town in the suburban belt of Budapest to evaluate and thoroughly analyze sustainability in the suburbs. Such research may need a general understanding of the situation in the entire Budapest suburban area. Given its high socio-economic and geographical complexity and vastness, however, it would be rather challenging to formulate generalizable statements as such attempts would necessarily lead to oversimplification of the situation and the tendencies, thus resulting in shallow arguments that may be supported by data overall but may be misleading, or even incorrect, in one or more specific locations.

For the analysis, we use a large pool of quantitative and qualitative data gathered in two major waves, 2017-18 and 2023. During the first wave, three focus group meetings were held, with six to twelve participants each, amended with in-depth interviews with residents and decision-makers. In May 2018, a survey with a sample size of 1002 respondents was performed that represented the town's adult population by gender, age, and neighborhood with a margin of error of ±3.1% at a 95% confidence level. The 2023 wave consisted of two focus group meetings in June, with 7 and 11 participants, and a survey in June and July. The sample size of the survey was 705 respondents representing the town's adult population by gender, age, and municipal constituency with a margin of error of ±4% at a 95% confidence level. In 2018 and 2023, the same set of questions were asked. The survey questionnaires were interviewed in person, and respondents were chosen using random walk sampling to evade uncertainties and deficiencies in the population register and enhance territorial representativity.

Due to the qualitative nature of the method, the focus group interviews are not statistically representative of the views of the population living in the area and were therefore used to complement the representative survey, interpret the results, argue, and get an insight into some specific aspects.

The period of five years between the two waves allows a limited longitudinal comparison, but the circumstances during the waves were significantly dissimilar. In 2018, Hungary experienced steady, relatively meaningful economic growth and a rise in living standards for five years with a positive outlook. In contrast, the pandemic between early 2020 and early 2022, the war in Ukraine from February 2022, and the resulting economic hardships, falling living standards, and rising inflation rates significantly altered people's attitudes, capabilities, and behavior. Therefore, the databases gathered during the two research waves enable the scrutiny of attitudes, behavior, and phenomena and test hypotheses under different economic situations in the same locality.

The authors participated in the compilation of the questionnaires, the development of the sampling methods of the two surveys, and the performance of focus group meetings, as well as the primary analysis of the databases of both research waves within formalized contracts with the Municipality of Törökbálint. The host of the databases, the Mayor of Törökbálint, granted access for the authors of this article to perform scientific analyses on the databases and publish results together with processed data but reserves its right to restrict the availability of the primary data, especially regarding the transcripts of the focus group interviews and the raw survey data files.

5. Results

In this paper, we do not aim to present the entire survey comprehensively but instead focus on three often criticized aspects of suburban living within the Smart Growth framework: 1) compactness, the quantity and quality of local services; 2) car use: mobility habits and modal split; 3) community: participation in local community activities and relations with the neighbors (‘the 3 Cs’).

5.1. Compactness – quantity and quality of local services

Previous research found [

50,

56,

68] that one of the typical problems of rapidly growing agglomeration settlements is the supply of services and commercial units in terms of quantity and quality. A detailed examination of the provision of commercial and human services, specifically focusing on identifying deficiencies in the supply, was conducted with a 22-item list in the questionnaire. Respondents were asked to evaluate the availability of services within their respective neighborhoods, rating on a scale of 1 (bad) to 5 (good). In addition, we were also interested in the locales where respondents access services, i.e., how far they travel out of the municipality to access various services, thereby contributing to heightened vehicular congestion.

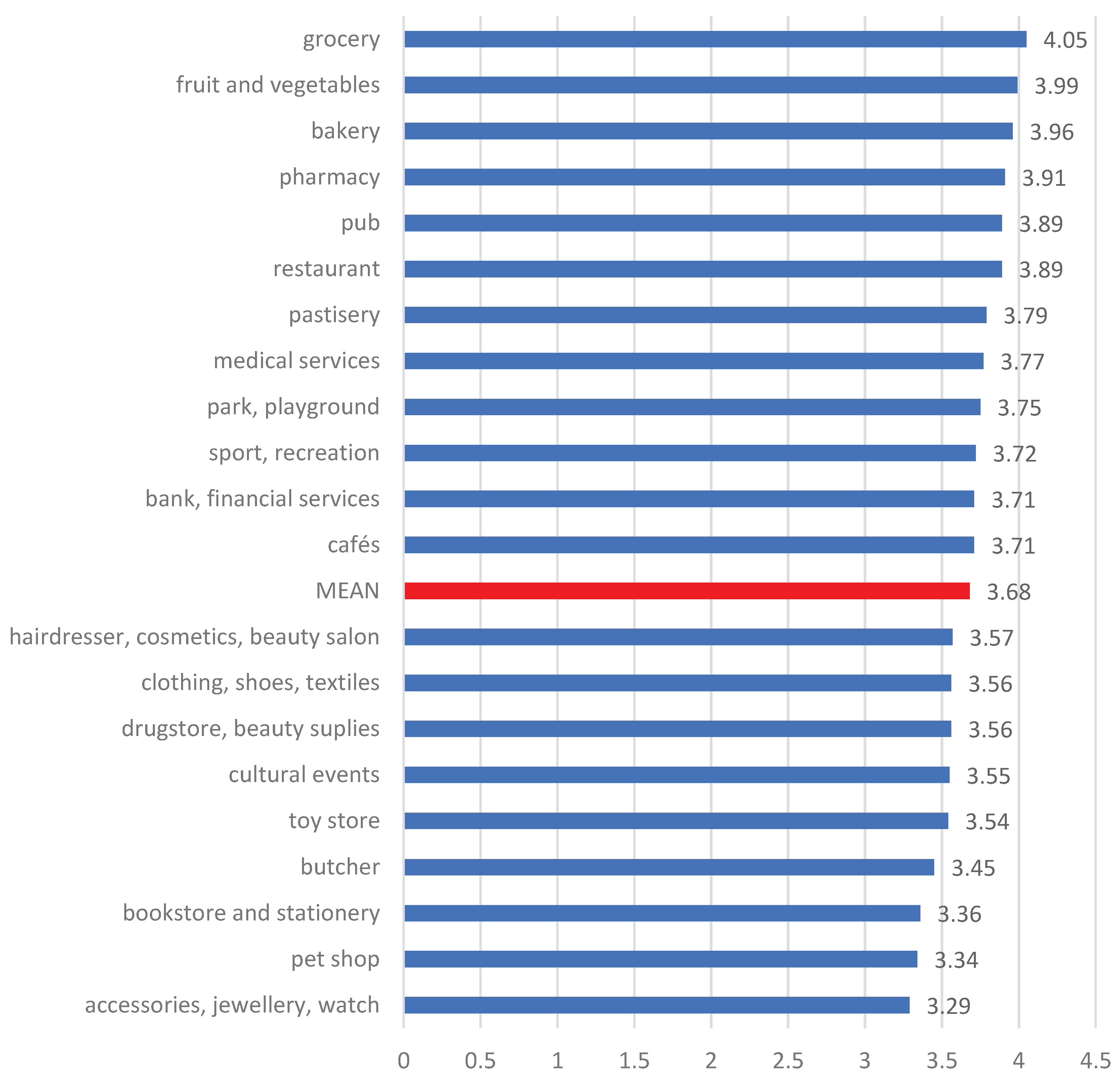

Figure 5.

Satisfaction with local services (1 – bad to 5 – good). Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 5.

Satisfaction with local services (1 – bad to 5 – good). Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Respondents were generally satisfied with the human infrastructure services. According to the 2018 survey, 60% of respondents can manage their daily needs within the locality of Törökbálint, and 65% were satisfied with the quality of educational institutions, which means that they do not or predominantly do not have to move away from the settlement, i.e., they do not generate a daily commute to the capital. Based on the average ratings, the overall perception of the availability of essential services such as grocery, fruit and vegetable stores, bakeries and pharmacies, cultural events, parks, playgrounds, and catering (restaurant, pastry shop) is positive, ranging between 3.7 and 4.0. This positive rating marks a slight improvement over the five years from 2018 to 2023 when we measured averages between 3.5 and 3.9. Identified gaps include 'urban specialty shops' encompassing watches, jewelry, accessories, clothing, shoes and textiles, toys, books and stationery, and drug and beauty stores. Nevertheless, there are significant disparities within the settlement: some parts of the town exhibit well-established service provisions, whereas others (especially the outskirts and allotment gardens) experience a deficit in amenities.

In practice, the respondents primarily access services in two areas: in Törökbálint and the capital. Törökbálint serves as the primary location for medical services utilization – 87%, compared to the 65% measured five years ago – and administrative activities – 92% compared to the 60% measured five years ago – the significant rise results from the recent opening of a medical center and public administration center in the newly erected townhall. As for shopping habits, more than 70% of the respondents do their daily shopping in Törökbálint, and only a minority of those who (presumably due to their daily routine) do their daily shopping in other settlements, mainly in the neighboring Budaörs, where significant malls and other commercial facilities are located. The dynamics shift, however, when considering weekly purchases, as approximately one-third of the respondents favor shopping in Törökbálint. In contrast, one-third opt for a shopping center in Budaörs. Notably, for social interactions such as meetings with friends and family events, locations beyond Törökbálint have assumed a slightly augmented role (18%). However, most respondents continue to engage in these activities locally – most of them taking place at home. Supplementary insights from focus group interviews that complement the questionnaire revealed that neither youth, young adults, nor middle-aged individuals find recreational opportunities locally. Although they have a favorable view of the Sports Center and the developments around the lake, they feel that these do not have sufficient appeal compared to the wide range of services the capital offers. It is typical for young people to arrange meetings in a café in a gentrified inner area of Budapest accessible by public transportation in fifteen minutes rather than meeting in a local entertainment facility. However, stylish restaurants and artsy pubs have begun to appear in town, mainly serving the better-off, older clientele.

5.2. Car use: commuting and modal split

More than one-third, 39% of respondents, may be categorized as commuters on at least workdays during the week, reflecting a slight increase from the 35% recorded five years ago. An additional 14% commute to the capital frequently, compared to the 10% reported half a decade earlier. Thus, more than half of respondents have a strong connection with the capital, an 8% increase compared to 2018.

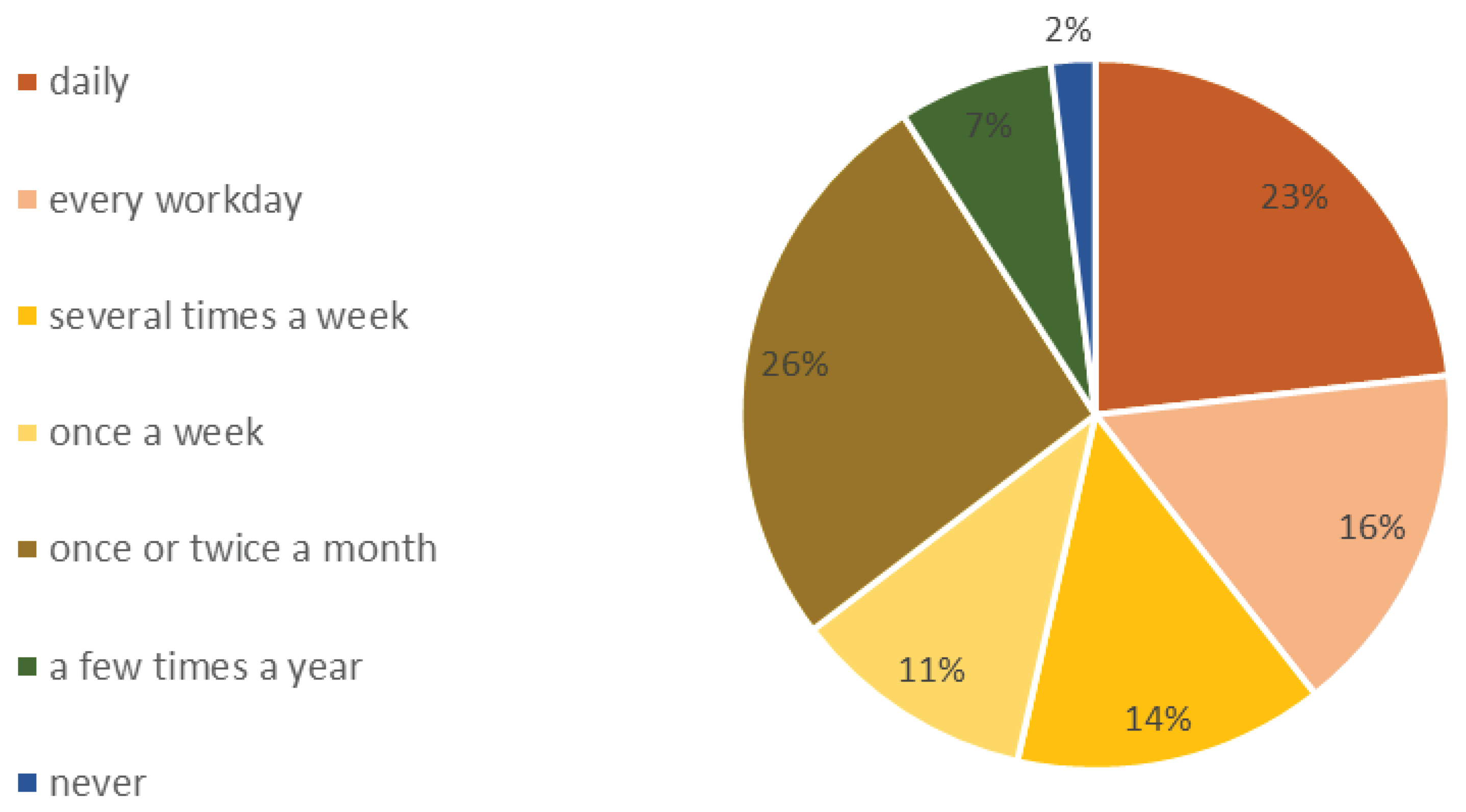

Figure 6.

Frequency of commuting to Budapest, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 6.

Frequency of commuting to Budapest, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Commuting is widespread among residents living on the outskirts of the town, where over 78% of respondents commute to Budapest daily. Younger respondents have a more intensive relationship with Budapest: almost two-thirds of those aged 18-24 and half aged 25-59 commute to the capital on working days. Individuals of higher socio-economic status demonstrate a more robust link with the capital, regularly traveling to Budapest for work and leisure.

The predominant mode of transportation for more than two-thirds of respondents is by car, representing a notable increase from 53% recorded five years ago. Conversely, 22% opt for public transport, indicating a decline of 11% compared to the 33% reported half a decade earlier, while 11% either walk or cycle.

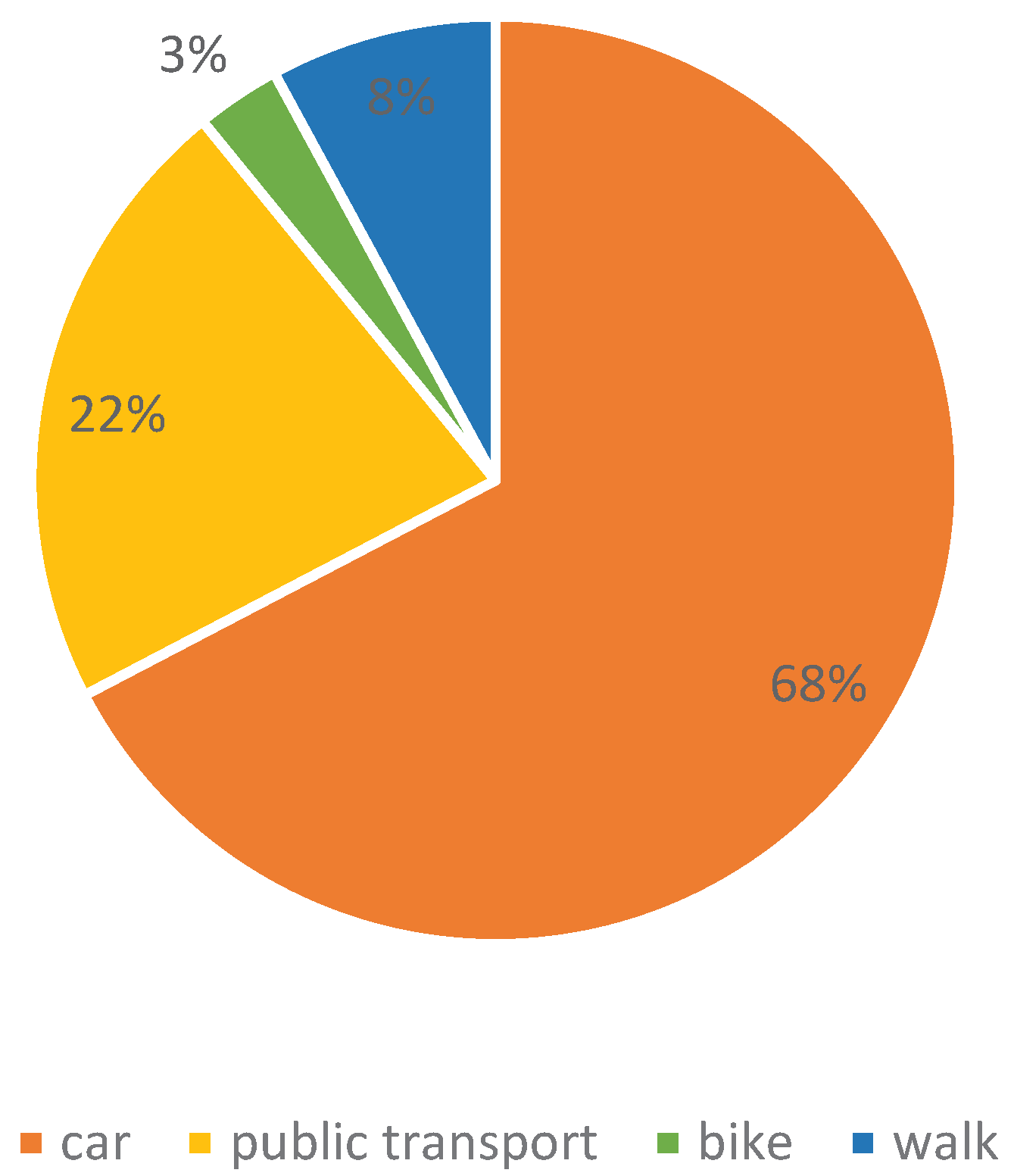

Figure 7.

Distribution of the most frequently used mode of transport, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the most frequently used mode of transport, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

44% of respondents use a car daily, while 17% use a car several times a week and 15% do not. Frequent car usage is particularly prevalent among the upper social status groups: two-thirds of them use their vehicles at least once a week. Notably, individuals aged 25-59 demonstrate a higher car use, with approximately 60% considered frequent users. Car use is particularly prevalent in the outskirts and allotment gardens. Regarding public transportation, buses operated by the capital's public transport company, which extends a comprehensive service in Törökbálint, are more commonly utilized by individuals with lower financial status, constituting approximately 21% of regular users, in contrast to 16% and 9% among those of medium and highest social statuses, respectively. The younger age groups predominantly utilize buses: the 18-24 age group emerges as the most frequent users, constituting approximately 46% of regular passengers. This proportion decreases sharply with age, with the oldest age group accounting for less than 10% of passengers who use the bus at least once a week.

The focus group participants considered the traffic situation critical. They felt that the morning and afternoon rush hours, mainly, were when traffic paralyzed the city, especially around institutions and major routes.

5.3. Community – participation in the community and trust in the neighbors

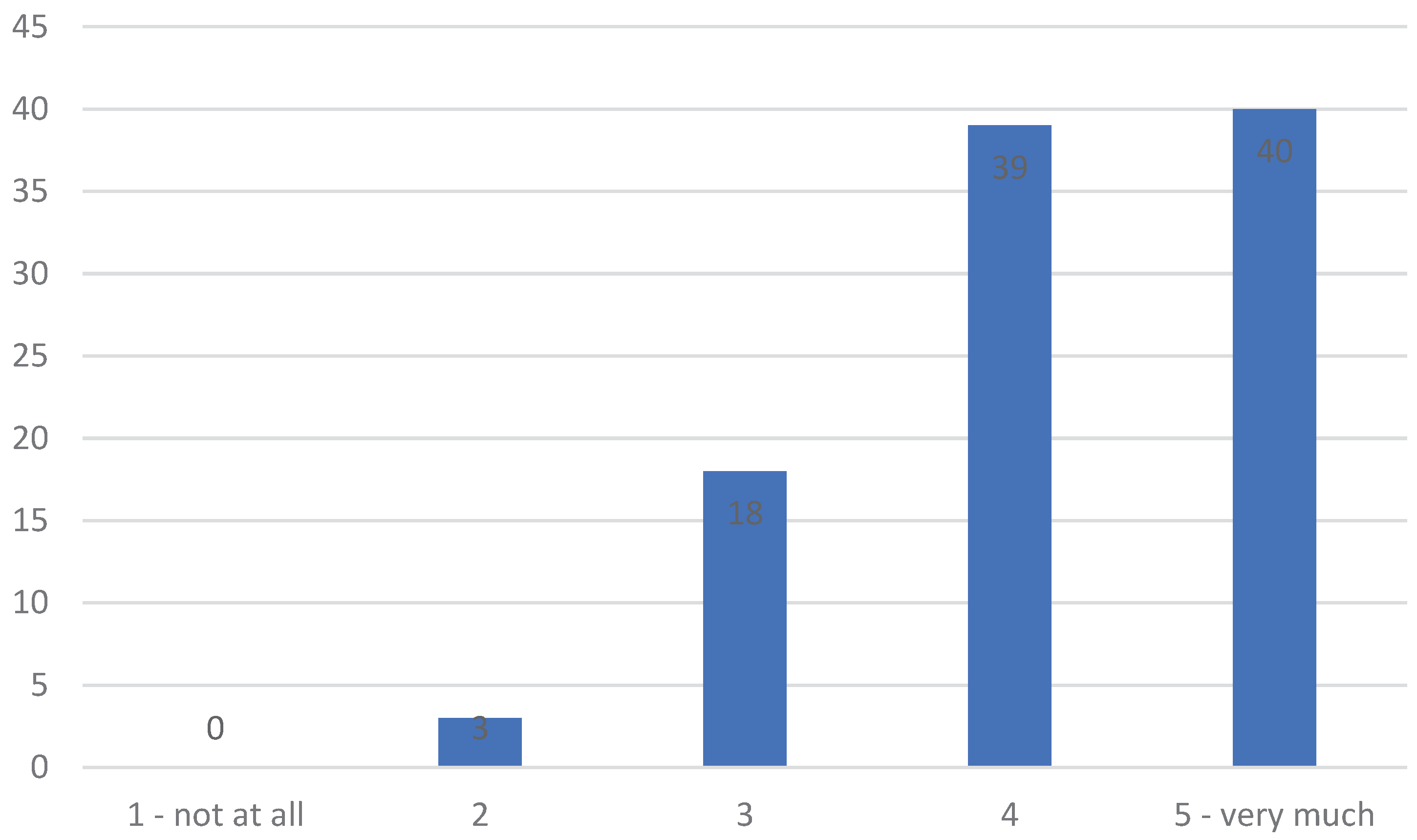

The findings of several studies underscore the significance of local identity, place attachment, and positive interpersonal relationships with neighbors as pivotal elements contributing to a settlement's long-term success and livability. The overwhelming majority of the population likes living in Törökbálint, with 90% of respondents expressing a favorable opinion of the municipality. Survey participants reported pretty strong relationships with their neighbors, with the vast majority knowing them relatively well and demonstrating considerable trust (rated on a scale of 1 to 5) both in their immediate neighbors (average 4.12) and in the population of Törökbálint in general (average 3.94).

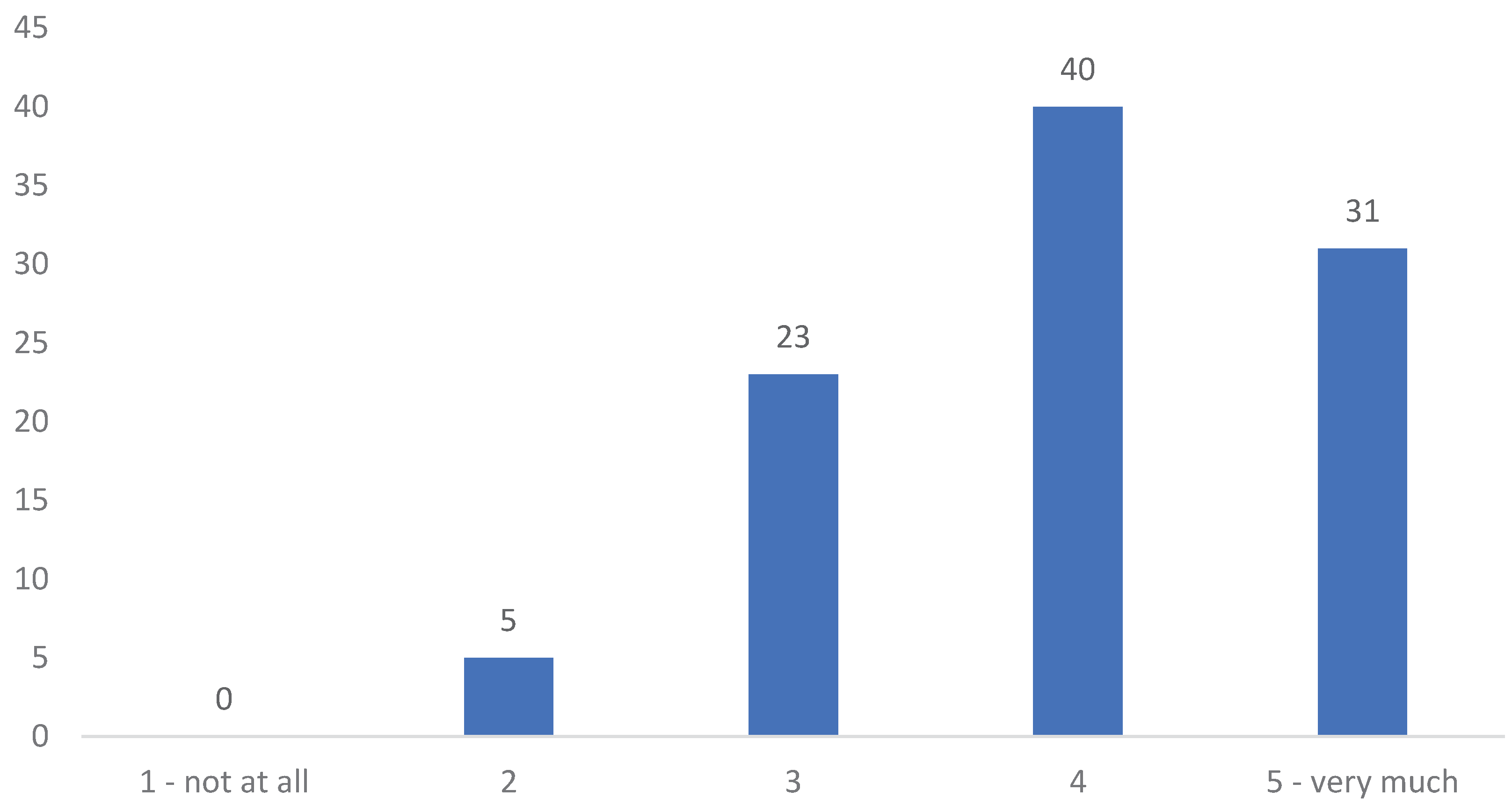

Figure 8.

Trust in neighbors, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 8.

Trust in neighbors, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 9.

Trust in the residents of Törökbálint, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Figure 9.

Trust in the residents of Törökbálint, percent. Source: Törökbálint survey, 2023, N=705.

Furthermore, a notable proportion of respondents (59%) indicate that their primary social network comprises friends and acquaintances within Törökbálint, while 16% maintain social connections predominantly external to the municipality. There is a significant correlation between a circle of friends and acquaintances and social status, aligning with national and European trends: individuals with higher levels of education and financial status tend to possess more extensive networks of acquaintances.

6. Discussion

When analyzing compactness, the results delineate a somewhat unexpected picture. Professional consensus in Hungary holds that suburbs heavily rely on the center for shopping and entertainment. The leaders in the municipality agree with such views. The data prove that the residents of Törökbálint mostly frequent local shops and services or do the shopping in the malls and stores of adjacent Budaörs, which is about five minutes by car and travel to the city only for exquisite or specialty goods and services. The overwhelming majority of residents are satisfied with the local human infrastructure, that is, educational and healthcare facilities, and use them in town.

Regarding compactness, the town shows preferential characteristics. On the other hand, its traditional center lacks an urban street view. Despite its traditional milieu and conventional functions, it serves less as a hub for locals, such as town halls, churches, and cultural centers. Consequently, a high level of compactness does not entail a more urbanized structure. The outcome is somewhat similar to the ripe suburbs in North America with highly developed but spatially dispersed commercial sectors [

69], where the presence of a historical but downgraded town center plays no significant role in this phase of development.

Entertainment and recreational opportunities are where the town cannot compete with the capital's wide range and sophisticated offers. The economy of scale in these sectors plays a more critical part. The venues and services of the capital lie too close and available where more demand allows the development of more complex and classy ones. The suburbs and the central city may not be regarded as separate entities; they are interdependent and intertwined, using the suburbs' and the center's infrastructure and facilities [

70].

The Törökbálint community shows vigor and solid social bonds that challenge the standard view of suburban areas as atomized, alienated, and disrupted societies. It performs better than most more urbanized areas in Hungary, creating fewer problematic issues with sustainability than other, denser areas. Its success fundamentally lies in the community's resilient and definite identity before suburbanization. It has served as a means to sustain the neighborhood in the waves of migration and attract and integrate the newcomers as members of the local society [

56]. Settlements with less developed or historically severely damaged local identities are likelier to have a less sustainable, more atomized, alienated local community [

50].

While the compactness and community analyses offer a positive view of the town's sustainability, commuting and car usage patterns depict a more multifaceted situation. As

Figure 4 shows, the car penetration in the town is not growing in line with the country's trends. The usage of vehicles has grown significantly recently, and the intensity of commuting to the capital has also increased despite the recent significant developments in public transportation servicing the area. Such tendencies contradict the positive tendencies of compactness. Strong polycentric development dually affects the suburban region around Törökbálint: commercial, shopping, and other opportunities and services have flourished, as well as other economic activities. Such services and businesses create a substantial demand for low- and medium-paid labor that commutes to the subcenter from other suburban towns and villages and from the capital [

56], usually by car, due to the less effective public traffic connections among suburban areas. Highly educated professionals, however, must still commute to the center for highly paid jobs that they usually accomplish by car. Polycentric development, thus, increases compactness on the one hand but contributes to the increase of commuting by building up new, more complex spatial connections, where the commuting needs of the low-income employees play a yet not fully considered factor [

71].

The town of Törökbálint has plenty of specifics that do not allow the generalization of this observation in a broader set of suburban towns but underpins the argument that urban and suburban areas may not be separated as antagonistically dissimilar in terms of sustainability; they are interlinked and part of the same urbanization process, as the Urban Political Ecology of Suburbanization expresses [

19]. The sustainability of suburbs is complex and different in various areas and may not be separated from related issues in more urban, denser areas. Moreover, the situation is changing with new aspects appearing in different communities. The sustainability of communities, therefore, is to be assessed in progress and in a context where urban and suburban areas may be judged to have failed or performed well.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we conscientiously concentrated on a well-targeted, comprehensive, and narrow-focused analysis. Thus, the lessons learned from the case study of Törökbálint may be generalized with strict limitations. Other towns and villages display strikingly different characteristics where similar scrutiny would probably lead to different conclusions. The complexity of Budapest's suburban belt, with more than two hundred towns and villages, would render such a generalized examination unachievable, but further studies and comparisons with other towns would shed more light on the complexity of the sustainability of suburbs. Using the Smart Growth framework while focusing on the three Cs of sustainability limits the scope of our research and gives valuable, in-depth insight. Such endeavors may be expanded horizontally, including more settlements, and vertically, with more aspects, but the clarity set for this paper may be challenging to attain.

Local history, identity, and desires of a community need to be considered as residents, stakeholders, and local decision-makers are dynamic actors in shaping their surroundings and future. For instance, the development of an urbanized center with a more appealing townscape and more commercial units, shops, and cafés together with condominiums that could offer demand for such services in the historic town center has been on the agenda for a long where small steps have already been taken in this direction [

56].

Polycentric developments in general, and fifteen-minute cities in particular, are considered beneficial for urban sustainability as they reduce the need for, and the average distance of, commuting. Our results show that such changes may lead to the opposite outcome, at least in the short run, if the demand and supply for jobs and services in a neighborhood or town do not overlap.

References

- Mumford, L. The City in History; Harvest Book: San Diego, 1961.

- Fishman, R. Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia; Basic Books: New York, 1987.

- Abbott, C. Suburbs: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: New York, 2023.

- Gans, H.J. The Levittowners: Ways of Life and Politics in a New Suburban Community; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, 1967.

- Davis, M. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. Verso: London, 1991.

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books ed.; Vintage Books: New York, 1992.

-

The Suburb Reader; Nicolaides, B.M., Wiese, A., Jackson, K.T., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY London, 2006.

- Gagnon Thompson, S.C.; Barton, M.A. Ecocentric and Anthropocentric Attitudes toward the Environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1994, 14, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Pepper, D. Anthropocentrism, Humanism and Eco-socialism: A Blueprint for the Survival of Ecological Politics. Environmental Politics 1993, 2, 428–452. [CrossRef]

- Bonnes, M.; Passafaro, P.; Carrus, G. The Ambivalence of Attitudes Toward Urban Green Areas: Between Proenvironmental Worldviews and Daily Residential Experience. Environment and Behavior 2011, 43, 207–232. [CrossRef]

- Epting, S. On Moral Prioritization in Environmental Ethics: Weak Anthropocentrism for the City. Environmental Ethics 2017, 39, 131–146. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.W.; Patterson, M.G. Bridging the Divide in Urban Sustainability: From Human Exemptionalism to the New Ecological Paradigm. Urban Ecosyst 2007, 10, 169–192. [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L. Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier; Penguin Books: New York, NY, 2012.

- Wu, J. Urban Ecology and Sustainability: The State-of-the-Science and Future Directions. Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 125, 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Dizdaroglu, D. Ecological Approaches in Planning for Sustainable Cities: A Review of the Literature. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management 2015, 1, 159–188.

- McPhearson, T.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Grimm, N.B.; Niemelä, J.; Alberti, M.; Elmqvist, T.; Weber, C.; Haase, D.; Breuste, J.; Qureshi, S. Advancing Urban Ecology toward a Science of Cities. BioScience 2016, 66, 198–212. [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. Horizontal Processes, Roads, Suburbs, Societal Objectives and Landscape Ecology. In Landscape Ecological Analysis: Issues and Applications; Klopatek, J., M., Gardner, R.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 1999; pp. 35–56.

- Tian, Y.; Wang, L. The Effect of Urban-Suburban Interaction on Urbanization and Suburban Ecological Security: A Case Study of Suburban Wuhan, Central China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1600. [CrossRef]

- Keil, R. Suburban Planet; Polity: Cambridge, 2018.

- Hobor, G. New Orleans’ Remarkably (Un)Predictable Recovery: Developing a Theory of Urban Resilience. American Behavioral Scientist 2015, 59, 1214–1230. [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Downtown Resilience: A Review of Recent (Re)Developments in Tempe, Arizona. Cities 2014, 36, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- Szántó, Z.O.; Kocsis, J.B. Smart Cities and Social Futuring; Working paper series; BCE Társadalmi Jövőképesség Kutatóközpont: Budapest, 2019;

- Allan, P.; Bryant, M. Resilience as a Framework for Urbanism and Recovery. Journal of Landscape Architecture 2011, 6, 34–45. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. Urban Resilience and Urban Sustainability: What We Know and What Do Not Know? Cities 2018, 72, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Polívka, J. Maturity, Resilience & Lifecycles in Suburban Residential Areas. city & region ; 1 2016. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, H.; Feng, Z.; Long, W. Regional Economic Resilience in the Central-Cities and Outer-Suburbs of Northeast China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2844. [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, C.; Hornik-Lurie, T.; Cohen, O.; Lahad, M.; Leykin, D.; Aharonson-Daniel, L. The Relationship between Community Type and Community Resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2018, 31, 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.; Wallace, R. Urban Systems during Disasters: Factors for Resilience. Ecology & Society 2008, 13, 18.

- Childers, D.; Cadenasso, M.; Grove, J.; Marshall, V.; McGrath, B.; Pickett, S. An Ecology for Cities: A Transformational Nexus of Design and Ecology to Advance Climate Change Resilience and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3774–3791. [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R. Climate Change and Urban Resilience. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2011, 3, 164–168. [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Y. Planning the Resilient City: Concepts and Strategies for Coping with Climate Change and Environmental Risk. Cities 2013, 31, 220–229. [CrossRef]

- Savitch, H.V. Cities in a Time of Terror: Space, Territory, and Local Resilience; Cities and contemporary society; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, N.Y, 2008.

- Dudley, M. Defensive Dispersal and the Nuclear Imperative in Postwar Planning: A Study in the Sociology of Knowledge, University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, 2000.

- Knaap, G.; Talen, E. New Urbanism and Smart Growth: A Few Words from the Academy. International Regional Science Review 2005, 28, 107–118. [CrossRef]

- White, S.S.; Ellis, C. Sustainability, the Environment, and New Urbanism: An Assessment and Agenda for Research. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 2007, 24, 125–142.

- Speck, J. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time; First paperback edition.; North Point Press, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 2013.

- Tóth, B. Mix-Use Developments in Phoenix and Tempe, Arizona: Sustainability Concerns and Current Trends. Folia Geographica 2023, 65, 55-77.

- Bohl, C.C. New Urbanism and the City: Potential Applications and Implications for Distressed Inner-city Neighborhoods. Housing Policy Debate 2000, 11, 761–801. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K. New Urbanism’s Role in Inner-City Neighborhood Revitalization. Housing Studies 2005, 20, 795–813. [CrossRef]

- Short, J.R.; Hanlon, B.; Vicino, T.J. The Decline of Inner Suburbs: The New Suburban Gothic in the United States. Geography Compass 2007, 1, 641–656. [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, B.; Airgood-Obrycki, W. Suburban Revalorization: Residential Infill and Rehabilitation in Baltimore County’s Older Suburbs. Environ Plan A 2018, 50, 895–921. [CrossRef]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E.; Speck, J. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream; 1st pbk. ed.; North Point Press: New York, NY, 2001.

- Duany, A.; Speck, J.; Lydon, M. The Smart Growth Manual; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2010.

- Grant, J.L. Theory and Practice in Planning the Suburbs: Challenges to Implementing New Urbanism, Smart Growth, and Sustainability Principles. Planning Theory & Practice 2009, 10, 11–33. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Tosics, I. Urban Sprawl on the Danube: The Impacts of Suburanization in Budapest. In Confronting Suburbanization: Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe; Stanilov, K., Sýkora, L., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, 2014; pp. 33–64.

- Kocsis, J.B. Patterns of Urban Development in Budapest after 1989. Hungarian Studies 2015, 29, 3–20. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Farkas, Z.J.; Egedy, T.; Kondor, A.C.; Szabó, B.; Lennert, J.; Baka, D.; Kohán, B. Urban Sprawl and Land Conversion in Post-Socialist Cities: The Case of Metropolitan Budapest. Cities 2019, 92, 71–81. [CrossRef]

- Csizmady, A.; Csanádi, G. Transitions in Budapest’s Agglomeration 1990–2005. USP 2021, 5, 112–125. [CrossRef]

- Hardi, T. Differences and Similarities in the Expansion of Suburban Built-up Areas around the Different City Regions of Three Central European Countries. TéT 2022, 36, 165–193. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, J.B. A Főváros környékének átváltozásai 1980 és 2020 között. Századvég 2023, 2023/3, 59–78.

- Losonczy, A.K.; Orbán, A.; Benkő, M. Contemporary Decentralized Development of a Centrally Planned Metropolis: The Case of Budapest. Urban Planning 2022, 7, 144–158. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Szabó, B. Urban Restructuring and Changing Patterns of Socio-Economic Segregation in Budapest. In Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West; Tammaru, T., van Ham, M., Marcińczak, S., Musterd, S., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, 2016; pp. 238–260.

- Bagyura, M. The Impact of Suburbanisation on Power Relations in Settlements of Budapest Agglomeration. Geographica Pannonica 2020, 24, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Egedy, T.; Kovács, Z.; Kondor, A.C. Metropolitan Region Building and Territorial Development in Budapest: The Role of National Policies. International Planning Studies 2017, 22, 14–29. [CrossRef]

- Egedy, T.; Kovács, Z.; Szabó, B. Changing Geography of the Creative Economy in Hungary at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2018, 67, 275–291. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, J.B. Recreating Locality: Community and Identity in Budapest Suburbs, 1995–2020. In Creativity from Suburban Nowheres: Rethinking Cultural and Creative Practices; Van Damme, I., McManus, R., Dehaene, M., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 2023; pp. 198–232.

- Csurgó, B. Vidéken lakni és vidéken élni: a városból vidékre költözők hatása a vidék átalakulására ; a város környéki vidék; Argumentum [u.a.]: Budapest, 2013.

- Kocsis, János B. A nagyváros útjában: A helyi társadalmak átalakulása Budapest délnyugati agglomerációjában. In Hely, identitás, emlékezet; Keszei, András, Bögre, Zsuzsanna, Eds.; L’Harmattan: Budapest, 2015; pp. 163–184.

- Vigvári, A. Zártkert-Magyarország: Átmeneti Terek a Nagyvárosok Peremén.; Napvilág Kiadó: Budapest, 2023.

- Egedy T. A kelet-közép-európai városrégiók átalakulása a posztfordi korban – elméleti alapok. Földrajzi Közlemények 2021, 145, 354–368. [CrossRef]

- Teveli-Horváth, D.; Varga, V. A Magyar Kreatív Fiatalok Lakóhelyválasztási Preferenciái És Annak Változása a COVID-19 Fényében. Tér és Társadalom 2023, 37, 71–91. [CrossRef]

- Vasárus, G.L.; Lennert, J. Suburbanization within City Limits in Hungary—A Challenge for Environmental and Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8855. [CrossRef]

- Illyés, Z.; Török, É.; Nádassy, L.; Földi, Z.; Vaszócsik, V.; Kató, E. Tendencies and Future of Urban Sprawl in Two Study Areas in the Agglomeration of Budapest. Landscape & Environment 2016, 10, 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Farkas, J.Z.; Szigeti, C.; Harangozó, G. Assessing the Sustainability of Urbanization at the Sub-National Level: The Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity Accounts of the Budapest Metropolitan Region, Hungary. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 84, 104022. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, J.B. Városfejlesztés és városfejlődés Budapesten, 1930 - 1985; Gondolat: Budapest, 2009.

- Csanádi G.; Csizmady A. Szuburbanizáció és társadalom. Tér és Társadalom 2002, 16, 27–55. [CrossRef]

- Suburban, Core & Urban Densities by Area: Western Europe, Japan, United States, Canada, Australia & New Zealand Available online: http://demographia.com/db-intlsub.htm (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Kocsis J.B. Térátmenetek - Város és pereme. Korunk 2023, 34/5, 3–11.

- Marshall, A. How Cities Work: Suburbs, Sprawl, and the Roads Not Taken. University of Texas Press: Austin, 2000.

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R. Importance of the Central City The Importance of the Central City to the Regional and National Economy: A Review of the Arguments and Empirical Evidenc. Cityscape 1995, 1, 125–150.

- Modarres, A. Polycentricity, Commuting Pattern, Urban Form: The Case of Southern California: Polycentric Commuting Patterns in Southern California. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2011, 35, 1193–1211. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).