‘When people look back […], they might be asking what were coaches doing when the planet was burning? Maybe the answer is… actually, coaches were just simply helping their clients to make the fire glow hotter. We’re focusing on amplifying individual and organisational performance, and those might be important issues, but what about the meta or hard to understand issues beyond those?’ (Jonathan Passmore, quoted in Boyatzis et al., 2022: 205)

Introduction

Non-sports related coaching is now a global, fast-growing, multi-billion-dollar industry (ICF, 2020), encompassing a wide range of services known as life coaching, career coaching, business coaching, executive coaching, team coaching, and so on. In this paper, ‘coaching’ refers to all of them. The professional providing such a service is called a ‘coach’, and the individual or group with whom the coach is working is called a ‘coachee’.

There is no single agreed-upon definition of coaching. It is usually considered one of the ‘helping by talking interventions’ (Tee and Passmore, 2022), with similarities and differences to counselling, consultancy, psychotherapy, training, teaching, mentoring, or mediation (Rosha, 2014). It has long been understood as an ideologically neutral tool for ‘unlocking a person’s potential to maximise their own performance’ (Whitmore, 2009: 9–10), a ‘collaborative solution-focused, result-oriented, systematic process in which the coach facilitates the enhancement of the life experience and goal-attainment in the personal and/or professional life of normal, non-clinical clients’ (Grant: 2003: 254), and a set of ‘technologies of the self’ in a Foucauldian sense, that is

specific techniques that human beings use to understand themselves […] which permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality (Foucault, 1988: 18).

ICF defines coaching as partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential. The process of coaching often unlocks previously untapped sources of imagination, productivity, and leadership.

The field has long been developed with very limited sociological input and there is a lack of research on how it relates to societal issues such as macroeconomic development, power dynamics and democratic governance, social stratification and inequality, social mobility, corruption, crime, etc. Although in sports coaching many have noticed that sociology is ‘the invisible ingredient in coaches’ knowledge’ (Potrac and Jones, 2019: 55-59; emphasis added) and suggested a wider range of sociological concepts to better inform the practice (Cushion, 2018; Jones et al., 2011; Lee and Corsby, 2021), non-sports coaching has largely evolved either with no consistent theoretical foundation or under the guidance of coaching psychology. In the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009 (Duignan, 2023), a growing body of critical literature has emphasised the need to analyse coaching as a social process and ‘an enabler for [desired social] change’ (Shoukry, 2017; Chiu, 2022; Gannon, 2021; Shoukry and Cox, 2018). Several social change-oriented frameworks have been proposed (see summary in Shoukry, 2017) and the International Coaching Federation (ICF) has released ‘tips for Incorporating Coaching for Social Change into Your [Coaches’] Work’ (ICF, 2019a). While recognising the progress that has been made, it is important to explore the limitations of these analyses, frameworks and guidelines in order to identify directions for improvement.

Change today, globally, is increasingly disruptive and dramatic. De la Sablonnière (2017) defines dramatic social change (DSC) as ‘a situation where a rapid event leads to a profound societal transformation and produces a rupture in the equilibrium of the social and normative structures and changes/threatens the cultural identity of group members’ (p. 12). Triggered by various events such as political upheavals, economic and legal reforms, technological innovation, booms of artificial intelligence, violent and powerful protests of large masses, massive migrations, wars, and natural phenomena, DSC is now ‘the new normal’ affecting millions of people worldwide (De la Sablonnière, 2017: 12). Examples of nondisruptive innovation giving us hope that ‘growth fuelled by nondisruptive creation occurs without incurring any industrial and social disruption and pain, thus helping to bridge the gap between economic and social good’ (Kim and Mauborgne, 2023: 19) are still few and far between. This is the new context in which coaching must operate. However, the above-mentioned analyses, frameworks, and guidelines did not take into account the DSC concept and did not question the relevance of the ‘classic’ (i.e. typically used and respected) approaches and models in today’s DSC world, overlooking the fact that ‘classics’ were developed in comparatively more stable natural, economic, political, and social contexts. The sociological perspectives they use do not address the nature and complexity of DSC. Thus, they define social change in a normative manner, as development or progress, focusing on social justice, inclusion, and emancipation. They specifically target ‘fringe’ groups such as the oppressed people and the change-makers, and their possible allies. Coaches are encouraged to adopt militant non-neutrality to help these people challenge and transform existing oppressive power structures; to help them cope with the consequences of crises and adapt to changes; to provide pro-bono services for impoverished people. These all are necessary and important. Nevertheless, the DSC nature implies more than just coping, adapting, increasing or at least maintaining well-being, and challenging and transforming established power structures. It also implies that people naturally and unavoidably co-participate in the ongoing construction of the emergent social and normative structures and socio-cultural identities/selves.

Therefore, directions for new developments arise to avoid having coaches and coachees work as unaware agents of unwanted or unsustainable individual, organisational, and societal dynamics. First, to appropriately address DSC, relevant sociological approaches must be developed. Second, different models, frameworks, and tools must be developed based on these new sociological approaches. Third, in DSC contexts, the middle of the socio-economic hierarchy must receive due attention because these people are massively affected by DSC-yielded identity breakdowns, facing risks such as a radical change in socio-economic position and nature of work, unexpected unemployment and impoverishment, a significant decrease in quality of life, silent or violent resistance to change, casual solutions that break the rules (i.e. undesired participation in growing criminality), or depression. Moreover, they account for the majority of people involved in the organisations’, communities’, and societies’ reconstruction precipitated by DSC. Supporting the re-construction of their selves and socio-cultural identities in line with the re-construction of better social worlds is therefore important and, along with education, coaching is in a unique position to help.

Aims, method and structure

This paper argues for a DSC-relevant sociologically informed paradigm shift in coaching practice and research, and for appropriate sociological knowledge and research methodology in the education of coaches. It aims to provide coaching practitioners, who rarely have a consistent sociological background, with critical reflections and basic sociological concepts relevant to DSC, explained in simple terms. It also suggests interdisciplinary research topics combining coaching sociology and coaching psychology.

The paper uses a layered autoethnographic account—which ‘focus[es] on the author’s experience alongside data, abstract analysis and relevant literature’ (Ellis et al., 2011: 278)—to reveal how a new way of practising coaching (hereafter referred to as ‘approach’ and ‘model’) emerged organically through 14 years of social constructionist-informed ethnographic observation and reflective practice by a sociologist-turned-coach. The new way of practising coaching meets the aforementioned development directions by (i) placing a DSC-relevant sociological approach at the core of the process and consistently building on it; (ii) helping every coachee develop psycho-sociological awareness and social change-oriented mindset and skills; and (iii) using a learning-to-develop through research (LDR) design. This paper does not intend to explore or provide evidence on the effectiveness of the new model, which shall be discussed in subsequent research articles.

DSCs have specific manifestations as they are triggered by different types of events and occur in different socio-cultural contexts. This paper is based on observations made in the context of the DSC triggered by the fall of the Romanian communist regime in December 1989. However, Romanian society has experienced a long chain of DSCs in little more than a century, triggered by various events in historically close succession: the creation of the independent modern nation-state; the First World War, followed immediately by the creation of the unitary state; the Second World War, shortly followed by the establishment of the communist regime; ultra-rapid communist industrialisation and urbanisation; and the fall of the communist regime and the abrupt opening up to Western ideologies, capitals, and technologies. As a result, it offers the methodological convenience of a complex and accentuated case of DSC, allowing an experienced observer to notice what may be present elsewhere only in nuce—and therefore difficult to observe. I believe the concepts proposed below may be paradigmatic and instrumental in other DSC contexts. A famous example of such a paradigmatic convenience case is the mental asylum, which allowed sociologist Erving Goffman (1961) to observe, in a democratic society, how a ‘total institution’ functions—some of the resulting concepts have proved relevant worldwide, in non-democratic societies.

The next section introduces the core theoretical assumptions. Thereafter, the basic sociological concepts relevant to DSC are briefly explained. Then, the paper elaborates on the ontological non-neutrality of coaching, illustrating the following: how coaching in DSC contexts participates in the joint social reconstruction, or reproduction, of self and cultures–ideologies–structures; how this occurs invariably and naturally, whether or not the process is intentionally conceived as ‘an enabler for change’; and how coaches and coachees in the DSC contexts can unknowingly contribute to unwanted social dynamics. Consequently, psycho-sociological awareness and a social change-oriented mindset emerge as the quintessence of coaching to address DSC. The rationale for a learning-to-develop through research (LDR) model of coaching is then discussed, and a related framework is proposed. Along the way, several common coaching assumptions and questions are challenged, elucidating why sociological knowledge and research methodology are needed in coaches’ education. Finally, a broader definition of coaching to address DSC is derived, the main limitations of the paper are highlighted, and suggestions are made for future interdisciplinary research directions.

A ‘stranger’ in the coaching field

I entered the field in 2009 with the mindset of a qualitative sociologist having worked on the (re)socialisation and identity (re)construction processes in DSC contexts triggered by the post-World War II establishment of the communist regime in Romania and the fall of it in 1989. I adopted an ethnographic participant–observer stance, regularly immersing myself in coach meetings (sales introductions and demos, peer coaching, workshops, conferences, and networking events) and initiating exploratory conversations with coaches, individuals who had received coaching, and potential clients. I met hundreds of individuals and listened, observed, and talked to dozens.

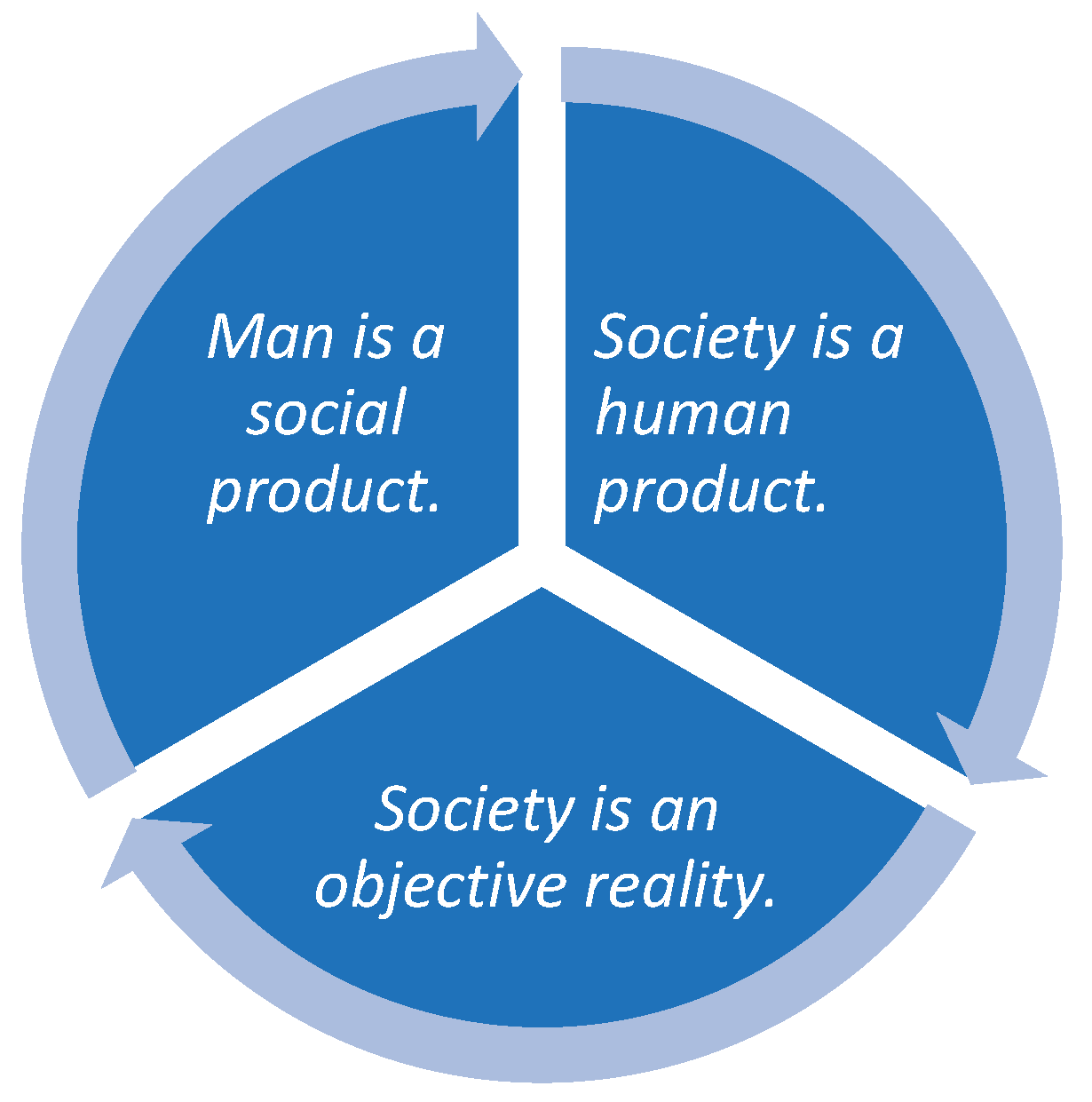

The leading sensitising concepts of my observations (Bowen, 2006) were based on the seminal theories of the social construction of reality (Berger and Luckmann, 1967) and of structuration (Giddens, 1984). Specifically, the following argument by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann (

Figure 1) seemed appropriate to the DSC context of the ‘transitional’ Romanian post-communist society:

Social order exists only as a product of human activity. No other ontological status may be ascribed to it without hopelessly obfuscating its empirical manifestations. Both in its genesis (social order is the result of past human activity) and its existence in any instant of time (social order exists only and insofar as human activity continues to produce it) it is a human product. (p. 70)

Society is a human product. Society is an objective reality. Man is a social product. (p. 79; emphasis in original; here, ‘man’ is used as a gender-neutral term, meaning ‘human being’).

By playing roles, the individual participates in a social world. By internalizing these roles, the same world becomes subjectively real to him. (p. 91; emphases added)

Berger and Luckmann’s argument has been refined by Anthony Giddens (1984), who conceptualised structure as relentlessly emergent and emphasises the structural-reproductive nature of human action:

The basic domain of study of the social sciences, according to the theory of structuration, is neither the experience of the individual actor, nor the existence of any form of societal totality, but social practices ordered across space and time [emphasis added]. Human social activities, like some self-reproducing items in nature, are recursive. That is to say, they are not brought into being by social actors but continually recreated [emphasis added] by them via the very means whereby they express themselves as actors [emphasis in original]. In and through their activities, agents reproduce [emphasis added] the conditions that make these activities possible (p. 2).

The above theoretical premises have implications for terms typically used in coaching, such as ‘potential’ (internal knowledge, structures, and processes), ‘goals’, ‘objectives’, ‘actions’, ‘non-actions’, level of ‘performance’, ‘authenticity’, ‘well-being’, ‘development’, ‘flourishing’, and so on. They imply that none of these are determined either inside or outside of the individual. All are built in a lifelong socially constructed relationship to the social worlds of which individuals are constitutive parts, and in the social (re)construction to which individuals co-participate through their everyday practices and (re)socialisation processes. This is not to ignore the facts that people are born with ‘considerable core knowledge, a rich set of universal assumptions about the environment’ and ‘brain circuits are well organised at birth’ (Dehaene, 2020: 119). However, we do not yet have conclusive evidence on whether there is any innate structure or concept that remains completely unchanged by social experiences, as stated by essentialist theories. Current knowledge indicates that all human innate structures and concepts are more or less reshaped by spontaneous and deliberate learning (everyday experiences and education), while every human being is able to ‘recycle’ in creative combinations the brain’s resources (Dehaene, 2020), i.e. both innate and learnt internal resources, and naturally co-participates in the simultaneous social (re)construction of their self and social worlds.

Consequently, I inferred that the motto of the coaching process in DSC contexts such as the post-communist transitional Romanian society should have been: ‘Let us, coach and coachee, be open and curious to explore what you can build better in yourself, your social worlds (e.g. families, friendships, fellowships, networks, organisations, local communities, insofar as they function as universes of discourse—see Clarke and Star, 2008), and your society’. In tandem, these questions must have been answered, among others: ‘What are you building in yourself, your social worlds, and your society through this self-conversation / outer conversation / real-life action?’; ‘What does that social world / society you want to participate in building look like?’; ‘What would that … (the coachee’s name) who can participate in building that world look like?’; ‘Who can that person build that world with?’.

Instead, the common understanding of coaching was, and for many still is, a simple, neutral, non-directive, structured or free-flowing conversation (Carden et al., 2023; Grant et al., 2010; Jones, 2020) aimed at facilitating people to achieve narrow SMART (specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic, and time-bound) goals, focused on individual or organisational performance, profit, well-being, and flourishing. The main theoretical assumption was ‘the inner game’ (Gallwey, 2008), which refers to the internal conversation and inner potential of the coachee. Following the teachings of Western coaches, my new colleagues were enthusiastic about their role in helping individuals and teams to, in coaching jargon, ‘unleash their full potential’ to reach specific one-off targets and their ‘best version’.

Behind the seductive assumption of ‘the inner game’, I often heard an over-simplified overuse of psychological concepts under an ‘it is about you and only you’ umbrella: ‘self-esteem’, ‘confidence in yourself’, ‘love for yourself’, ‘authentical self’, ‘what you like’, ‘how you feel’, ‘what you gain/lose’, and so on. ‘The inner game’ was not consistently linked to the social game. I call this over-psychologisation. I wondered how this coaching would have participated in the problematic ongoing reconstruction of different social worlds and society after the fall of communism. The same question must be asked in any DSC context.

I also pondered the meaning of ‘unleashing the full potential’: when could one’s potential be considered fully unleashed? Any internal process activation and inhibition are context-dependent. Moreover, each new experience enriches the potential. These imply that the potential can never be ‘fully’ unleashed in any specific situation. I had a similar question on ‘best version’ and its difference from ‘doing one’s best’: when could one consider having reached their ‘best version’? The ever-evolving nature of human beings, depending on the context, implies that nobody ever knows what their best version could be. Both phrases are either built on essentialist or strongly normative beliefs or have no empirical or theoretical basis.

Eventually, I realised that I was a Simmelian ‘stranger’ in the social world of coaching, with the inevitable discomfort and benefits that usually come with it:

his position in this group is determined, essentially, by the fact […] that he imports qualities into it, which do not and cannot stem from the group itself. […] His position as a full-fledged member involves both being outside it and confronting it. […] He is not radically committed to the unique ingredients and peculiar tendencies of the group, and therefore approaches them with the specific attitude of “objectivity” […] Objectivity may also be defined as freedom: the objective individual is bound by no commitments which could prejudice his perception, understanding, and evaluation of the given (Simmel, 1950: 402-404).

After about a year of participant observation and documentation, I took the risk to develop a different coaching practice, continuing to attend coach meetings as a ‘stranger’. I worked for 14 years as an independent professional with several hundred people, individually and in groups. A few were students and the majority were employees, managers, and small and medium-sized business owners in IT, law, health, education, banking, sales, marketing, administration, and the arts. The youngest were 16 years old, and the oldest were 56 years old. Most initiated the process themselves and paid for it, in full or in part; some asked for and received financial support from their organisations; for some, their managers or parents initiated the process and made the financial arrangements. About two-thirds were middle-class, university-educated Romanian Orthodox women aged 25–50 years, some living in Romania and some in the European diaspora. All adults were people in social mobility; I define the concept in the next section.

Basic generative sociological concepts for coaching to address DSC

I refer to the concepts that inform coaching models and practice as ‘generative’ because all the resources that coaches bring to the conversation (e.g. summaries, questions, rephrasing, reframing, shared emotions, feedback, explanations, or silences) stem, consciously or unconsciously, from them. We are talking about different approaches precisely in that each approach is unique in the range of core generative concepts it offers to the practitioner. A clear awareness of their generative concepts enables coaches to avoid misleading and dangerous interventions and give structure to the conversation, and the professionalisation of coaching requires deliberate use of the generative concepts. Hence, I briefly explain some of the basic concepts of the sociological approach I propose in this paper.

In addition to the theoretical assumptions mentioned above, the unavoidable core concepts for coaching to address DSC are indicated by its characteristics: ‘rapid pace of change, rupture in social structure, rupture in normative structure, and threat to cultural identity’ (de la Sablonnière, 2017: 12).

Socio-cultural identity refers to the memberships and ways of being that underpin the answers to the question, ‘Who am I in relation to other people, individuals and groups?’. It is context-dependent and is (re)constructed over the course of a lifetime through socialisation and resocialisation processes, during which people incorporate, naturally or willingly, social and normative structures (Burke and Stets, 2009; Mead, 1934). The self-made identity, a core concept in most coaching processes, especially in life coaching, therefore involves several issues linked to ‘the paradoxical nature of the desire for self-creation’ (Pagis, 2016: 1).

Social structure is rarely used consciously as a generative concept in coaching, although it appears in coaches’ vocabulary when asking about roles, power, and relationship patterns. It has various meanings in sociological literature. In the context of this paper, it refers to human collectivities or groups and their patterns—i.e. relatively stable, taken-for-granted and routinely reproducible ways—of relating to each other, in terms of positioning, roles, power and life-chances (Weber, 1978), more or less regulated by institutions. Social structures operate as strata and hierarchies—sometimes the terms social structure, social stratification, and social hierarchy are used interchangeably. They can be represented as ‘maps’ of positions that indicate legitimate ‘territories’, ‘boundaries’, and ‘pathways’ for individual and collective access to key social resources.

People socio-cognitively and historically construct various and dynamic social structures on the basis of different criteria such as age, gender, place of residence, education, employment, occupation, income, nationality, ethnicity, religion, and so on, taken separately or in various combinations; socio-cultural identities are built on the basis of such socio-cognitive and historical constructions. Consequently, human collectivities/groups to which ‘social structure’ refers may be bounded by a specific physical space (e.g. nation-states and local communities), or may have no spatial boundaries (e.g. people having the same age, gender, religion, education, profession, or income level).

Institutions are inextricably linked to social structure and are sometimes equated with social structure. However, they are only instruments that people create, maintain, and change in order to regulate and control social relations. They consist in social definitions of status-roles and procedures, i.e. the expectations that people can legitimately have of each other within and between social collectivities, and for the respect or violation of which they can be held accountable and formally or informally rewarded or punished. Once established, institutions serve as instruments of legitimate social power determining the likelihood that individuals from some social groups will impose their will on the feelings, thoughts and actions of individuals from another social groups, by various means and even against all resistance (Weber, 1978).

Life-chances (Dahrendorf, 1980; Weber, 1978) refer to people’s right and opportunity to access key social resources and to use them effectively and efficiently to stay alive, meet their human needs, and continuously improve their quality of life to the best possible level in their social worlds and societies. Life-chances encompass

Everything from the chance to stay alive during the first year after birth to the chance to view fine art, the chance to remain healthy and grow tall, and if sick to get well again quickly, the chance to avoid becoming a juvenile delinquent—and very crucially, the chance to complete an intermediary or higher educational grade […] (Gerth and Mills, 1953: 313).

In modern societies, life-chances also include the possibility for individuals belonging to different groups to change their place in the social structure. This process is called social mobility. It can be upward, downward or sideways, either compared to parents’ place (intergenerational mobility) or over the course of a lifetime (intragenerational mobility). This is particularly important for coaching in DSC contexts, as most of the coachees are people in social mobility.

Normative structure refers to the collectively accepted ‘musts’, a set of principles, values, norms, rules, and rituals that guide people in using the social ‘map’ provided by the social structure, legitimately enabling or prohibiting and facilitating or hindering individuals belonging to different collectivities/groups from accessing key social resources. In today’s societies, three types of normative structures coexist, mutually endorsing or conflicting with each other: written and formal structures (laws or equivalents and organisational rules, adopted and implemented using modern bureaucratic institutions); unwritten and informal structures (sets of shared values, norms, and rituals of interactions, which regulate people’s behaviour by cultural/traditional institutions); and intellectual and non-formal structures (scientific and philosophical ideas produced and supported by knowledge institutions such as universities and research centres, and disseminated more or less accurately through media such as educational programmes, books, journals, blogs, conferences, podcasts, and journalistic interviews with experts). Typically, intellectual products are not seen as normative structures. However, in the contemporary ‘knowledge society’ (Giddens, 1990), when people—experts or non-experts—assert, practise, or oppose a set of intellectual ideas, others may identify them as members of a particular social group or social world. Thus, shared knowledge facilitates or hinders people’s admission into a group and access to its social resources, functioning as effective group norms.

The above normative structural pluralism is even more complex and contradictory because, throughout history, normative structures of the powerful have been imposed or imported into powerless societies where they now coexist and intertwine with the local ones. Conversely, critical masses of people have migrated within more developed countries, bringing their social and normative structures and making them a matter of concern for the receiving community/society. Current global dynamics are moving towards growing complexity of social and normative structures.

Social and normative structures are established, reinforced, and maintained largely by the symbolic power of ideology. Ideology refers to ‘cultural beliefs that justify particular social arrangements, including patterns of inequality’ (Macionis, 2010: 257; emphasis added) and a corresponding body of symbols and repetitive spoken or written ideas that express the ways of living, thinking, speaking, and writing of a particular social group. When the coachee creates narratives about what and why they or others want, say or do—and do not want, say or do—and the coach chooses to help in a way or another, any cultural product can be recycled and used, consciously or unconsciously, in an ideological manner. That is, every coaching conversation expresses, and sometimes obscures, social and normative structures that have been incorporated during successive (re)socialisation processes of both coachee and coach.

I condense the aforementioned ideas into ‘culture-ideology-structure’ (CIS) and assume that the most useful concept to understand for human life today is the individual/group seeking to achieve their own projects in a specific and dynamic pluralism of CISs (Stănciulescu, 2002: 59–70).

CISs, incorporated and present, work for individuals and groups as both resource pools and constraints, with agency—that is, individual and collective awareness and effective activation of them as resources—making a difference. However, many people believe that structure only means coercion, limitation, lack of freedom and authenticity, and overlook or even resist structural resources, thereby unconsciously limiting their life-chances; or, conversely, embrace the fashionable slogan ‘No limits’ and overlook structural constraints, unwittingly limiting the life-chances of others and exposing themselves to avoidable social sanctions. Furthermore, everyone’s life-chances are determined by their awareness of the CISs in use and their ability to play by socially accepted values-principles-norms-rules-ideas. Coaching should help people understand the true nature of their choices and actions, which are always socially circumscribed, the ambivalent nature of CISs, as well as their own interest and responsibility to use them appropriately as resources and to consciously participate in the reconstruction of the desired CIS. It should help people become aware of and navigate through ambiguous CIS pluralism. These can only be achieved if coaches have the necessary sociological knowledge. No coachee or coach enters the coaching process simply as an individual. Instead, each interacts with the other as a specific exemplar of multiple social worlds, that is, as a specific mosaic of pieces coming from all those collectivities. The very opportunity to access a coaching process, the choice to use that opportunity, and the ability to make it effective in one direction or another depend on both the CISs the coachee has incorporated and the CISs they are currently operating in. The same applies to the coach’s opportunity to become a coach, to choose one approach/model or another, and to be successful as a professional.

As defined above, DSC implies ruptures in the CISs, precipitating painful threats and ‘earthquakes’ to socio-cultural identities, and in-depth reconstruction of both CISs and selves. Coaching in such a context must take this reality into account in order to avoid inadvertently acting as an instrument of unwanted dynamics. ‘Life-chances’, ‘increasing life-chances’, ‘social positioning’, ‘social power’, ‘social structure’, ‘social mobility’, ‘normative structure’, ‘ideology’, and ‘structural pluralism’ should therefore be basic generative concepts.

I further elaborate on how the above concepts impact the coaching process by referring to my reflective practice as a sociologist-turned-coach in the post-communist Romanian society, which I propose as an accentuated case of DSC present globally in various stages and manifestations.

The ontological non-neutrality of coaching

In Romanian society, traditional local and modern Western-inspired CISs have long coexisted, altering each other, with the former winning over the latter in daily practices (Ralea, 1943; Stahl, 1939). The totalitarian CIS made this mix more complex. Behind organisational or legal rules, people reinforced the outside-the-rules ‘underlife’ (Goffman, 1961) as the normal way to live—in a sociological sense, ‘normality’ refers to ‘a collective representation perpetuated in interactional rituals’ (Misztal, 2015: 1), a behaviour that is familiar and taken for granted by many, who consider it necessary and acceptable, or at least tolerable. They developed a ‘demonstrative complicity’ in deceptively ‘juggling the rules’, just pretending to follow the rules and collectively manipulating appearances to ensure that officials and possible snitches or gossips could not see, or prove, that the rules had been broken (Stănciulescu, 2002: 93–147). The post-communist opening allowed additional Western and Asian CIS components to enter the highly heterogeneous mix, precipitating an exceptionally complex amalgam of CISs, with no clear contours—this complexity is what makes Romanian society an accentuated case of global DSC. None of the CISs managed to gain relatively stable authority—i.e. accepted power—over a majority, a situation called ‘legitimacy crisis’. This crisis of legitimacy has been fuelled by and has itself fuelled the ‘underlife’ parallel to or against the official rules/laws and the ‘demonstrative complicity’ in deceptively ‘juggling the rules’, which remain sociologically-normal components of the post-communist social life (Stănciulescu, 2002: 71–92; Stoica, 2012).

In contexts ruled by such a CIS pluralism, individuals and groups do not have clear ‘maps’ of which social resources can sustainably increase life-chances and which are the right ways to obtain them. For almost any goal, means, and action/inaction, they can find convincing pros and cons in one or more CISs, along with social pressure and social support or social sanctions. Hence, they have a high probability of losing their path even when they are sure of being on the right track or vice versa. All people except those with radical beliefs unconsciously construct their desires, goals, narratives, and reasons for acting/not acting as an open and unstable mosaic (open kaleidoscope) comprising heterogeneous and often contradictory pieces from different CISs. The more networks, information, and experience vary, the more people can ‘juggle’ their pros and cons, becoming unstable and unpredictable in their choices and engagements. The high degree of CIS pluralism’s complexity, ambiguity, and volatility leads to a high degree of disorientation, high instability and unpredictability of choices, and inconsistent, ‘slippery’ memberships—both in and out and, at the same time, neither in nor out ‘to the full measure’. I termed this both-and, neither-nor or, in short, both-neither action/identity/self (Stănciulescu, 2002: 9). This deserves to be tested as an explanatory hypothesis for the fact that ‘the biggest challenge that organizations are facing today [internationally] is not only managing these [human] resources but also retaining them’ (Bidisha and Mukulesh, 2013: 8).

No coachee is ‘the expert—of the issue at stake and of the systems they operate in’ (De Dominicis and Stelter, 2023: 25) in DSC contexts, as many coaches still assume. Some, if not most, of one’s inner resources, shaped by past experiences, are outdated. In contrast, new reference groups and significant others are often perceived unrealistically, based on appearances, and followed uncritically, paving the way for a high vulnerability to deception and manipulation. The following examples illustrate this concern.

A middle manager wondered whether she should change her job and whether a new job abroad would better address her needs. She confessed to feeling uncomfortable regarding the recurring changes in her company, which apparently prevented her from developing a respected professional identity. Changing top managers within three years seemed excessively frequent to her need for stability and security—in the ongoing global volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous context (VUCA; Bennett and Lemoine, 2014), this revealed an obsolete and unrealistic mental model of reality. She expected that her recognition would follow her silent achievements without her actively making her work known to the new managers—‘Let others praise you, not you thyself’ is the traditional model adopted and reinforced by the totalitarian CIS, which still works today as a ‘moral’ tool to reproduce, unconsciously or deliberately, the inequality in life-chances. She decided to stay with her employer, balancing her need for stability with her need for development. She learned to act purposefully to build the respected professional identity she wanted, balancing her modesty with the necessary assertiveness. At the time of writing, she is on a path of upward social mobility and is also helping others to understand how the ‘inner game’ is socially embedded.

A young employee was seeking a different ‘good career and life’. He was confused by competing social messages—his parents’ traditional ‘this is a good job, you have a secure monthly salary’ and the rapidly growing CI of ‘do what you like, if not, you will not be happy’, endorsed by numerous coaches; the meritocratic ideology of ‘study and work hard’ and the new CI of ‘learn what you like’, again endorsed by numerous coaches. I asked, ‘Give me the names of three people who have a good career and life, stating they only did what they liked when they were your age, and had socio-economic, cultural, and educational backgrounds similar to yours’. He discovered that ‘do/learn what you like’ benefits people belonging to privileged socio-economic categories—they could afford to do/learn what they liked because they either benefited from their family or local community resources and/or had accumulated significant internal and external resources by doing/learning what they did not necessarily like before doing/learning what they liked. However, he decided to play the fashionable ‘do what you like’ game. After about ten years, he realised that he had made, in his words, ‘the wrong choice’ and asked for a new programme.

A lawyer specifically asked for ‘tips and tricks’ on how to manipulate her colleagues to vote in her favour in a competition for a prominent position; she assumed that, as a sociologist, I would be competent to support her project. I explained that my values firmly prevent me from helping with manipulation, and that coaching is not simply about teaching tips and tricks. ‘Are there any rules?’, I asked. ‘You know, rules are made to be broken’, she answered, using a common saying. ‘Would you be open to exploring the values behind those rules and how they might be consistent with your identity and the world you want to live in?’, I asked again. ‘I have never thought of these rules in this way’, she confessed, and accepted the challenge of a coaching programme that could help her increase her chances of fair success.

If the coach had embraced the assumption of the coachee-expert, the coaching process, which is designed to help individuals become future-oriented and realistically ambitious, would have run a high risk of unthinkingly keeping them stuck in the past, which they wanted to and should leave behind, or of allowing them to be entrapped by catchy illusions. Coaches are neither experts who provide ready-made solutions nor are they old-fashioned teachers who only convey knowledge. Besides, in DSC contexts, they share the same high level of objective ignorance—that is, the ‘intractable uncertainty (what cannot possibly be known)’ (Kahneman et al., 2021: 140)—of their coachees. However, they must have sufficient knowledge regarding social complexity and dynamics to help the coachees understand that (i) they combine different frames of reference that fit different CISs; (ii) through their choices of goals, ways, and means, they effectively reinforce one CIS or another, and may participate in the social construction of desirable or undesirable CISs dynamics, which may enhance or jeopardise their life-chances in the long run. Without sociological knowledge, one deludes themselves into thinking that a ‘good question’ is being asked.

For instance, when the coaches ask supposedly ‘neutral’ and ‘non-directive’ questions, such as ‘What do you like/want?’ or ‘What is your intuition telling you?’, they make the coachees momentarily happy by inducing a deceptive and transient sense of power. Yet, if the coachees do not belong to an advantaged social category, such questions may unconsciously make coaching a tool for reproducing and increasing social inequality. This is because likes, dreams, goals, values, beliefs, intuition, languages, and willingness to act or abstain from acting are not generated, as many coaches assume, simply by the coachee’s uniqueness, authenticity, free choice, and willpower, or special natural or supernatural gifts; nor are they simple manifestations of a presumed-neutral ‘cultural self’. Rather, they are deeply rooted in the CIS conditions of their biographies and the actual conditions of their actions. The analyses of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1987) revealed these CIS roots even in the case of likes and dislikes commonly deemed just ‘personal’ or ‘cultural’, such as aesthetic ‘good taste’. Perfect socially-free will is no more than an illusion. People cannot choose to let themselves either be influenced by others or, on the contrary, act according to their ‘authentic self’, as many coaches and coachees believe. At best, they can only be aware of and choose which others, carrying which CISs, influence them. This is difficult to do in our contemporary societies because real contexts are very complex and ambiguous, being ruled by more than one CIS, some of which may not be evident.

Similarly, if coaches asked, ‘What did you do in similar situations in the past?’ or ‘What is your intuition telling you?’ to people who used to think that the out-of-rule/law ‘underlife’ and the ‘demonstrative complicity’ in deceptively ‘juggling the rules’ are ‘normal’, they would make those coachees feel respected and help them find an efficient solution. However, such coaching would reinforce the perceived-normal violation of rules/laws, thus unintendingly feeding criminality, endemic corruption, or endless social unrest/conflict.

The above developments are in line with previous studies suggesting that coaching should not be a simple neutral questioning (Gannon, 2021; Shoukry and Cox, 2018; Shoukry and Fatien, 2023). However, they pinpoint that non-neutral coaching should be understood not only in a militant-normative sense but primarily in an ontological sense. Irrespective of what the coaches do, their interventions and coachees’ narratives and answers are deeply rooted in a CIS pluralism, instead of neutral cultures, and contribute to the strengthening and reproduction of one CIS or another. The presumed ‘neutrality’ and ‘non-directiveness’ of the coach are asociological assumptions. Not suggesting ready-made solutions and being ‘neutral’ and ‘non-directive’ are different concepts. Indeed, the more the coaches claim to be ‘neutral’ and ‘non-directive’, the more they act ideologically because being unaware of something does not mean that it does not exist and exert any effect; instead, it has an uncontrollable effect. If I am not aware of my CIS biases and do not help the coachee view theirs, both of us may be unconsciously co-manipulated because we inevitably learn from each other, and we cannot detect the hidden CISs embedded in my presumed ‘neutral and non-directive’ interventions and their answers. If I am aware of my biases and help the coachee become aware of theirs, we can be vigilant and better protect ourselves. Thus, both of us could train ourselves in critical thinking during coaching sessions, which would be more ethical than a naïve ‘neutrality’.

Developing psycho-sociological awareness and social change-oriented mindset

For coaches to provide effective interventions and coachees to generate life-chances increasing solutions, both must develop: (i) psycho-sociological awareness—that is, learning how to explore and discover the CISs embedded in their and others’ ways of thinking and acting, and thinking critically about these issues; and (ii) a social change-oriented mindset—that is, understanding that they co-participate in CISs reproduction or reconstruction, and learning how to make choices and act consistently to improve life-chances in a sustainable way. The following examples clarify and introduce new generative concepts relevant to coaching in DSC contexts.

Another female manager wanted to gain trust and recognition at work while adhering to a feminist ideology and ensuring that her ‘true, authentic self’ was ‘modest, not wanting to upset anyone’. The conversation’s turning point, which she appreciated as likely to open the door for increased life-chances, arrived when she became aware of the three CISs that she was holding simultaneously (traditional, modern-feminist, and neoliberal-managerial). What she thought of as her ‘true self’ was only one part of a multiple and contradictory self (Elster, 1987; Hermans, 2001; Lowery, 2023). She understood that both being ‘modest’ and being ‘efficient’ have CIS significance and discovered how to resist her and others’ judgements and nurture a new self, able to co-participate in building the social world she wanted to live in.

An ‘egalitarian’ husband honestly sought to improve the quality of his family life. He resisted his wife’s desire to become financially independent and invoked ‘practical reasons’ for him to make all the payments. Insofar as they remained in the psychologically informed ‘my perspective–your perspective’ approach, they deepened the conflict. The conversation’s turning point arrived when he understood the embodied contradictory CISs behind his narrative. He decided to support his wife’s autonomy. However, he said that he would make deliberate situational choices about acting as a ‘traditional man’ or an ‘egalitarian man’ outside the family. His social memberships, wherein different masculinity patterns were valued and likely to nurture functional relationships facilitating access to specific resources, required a flexible ‘scene’-dependent self (Lahire, 1998).

A university professor complained that the head of her department frequently imposed administrative work on her, ‘like a dictator’, thus leaving her with less time-energy for teaching preparation and research responsibilities, which she liked doing. She made causal imputations based on personal traits and intentions—a well-known attribution error, exacerbated by previous totalitarian experiences—and saw no solution but to resign, though she wanted to retain her job. ‘It is such a relief to understand that it is not a question of individuals’ characters and intentions, but of different incorporated social worlds’, she confessed after understanding that her need for professional fulfilment and autonomy and his need for status-based power and control had been developed in different social worlds with different CISs. From this point, which I conceptualised as de-subjectivation or objectivation of the problem, she worked to rebuild their relationship and performed better at her job with less stress.

None of the people I coached manifested a natural, innate, stable, coherent, unambiguous ‘authentic’ self, as many coaches consciously or unconsciously expect when asking ‘Who are you (for real)?’. Each of them revealed a multiple ‘dialogical self’ (Hermans, 2001), a composite of parts speaking on behalf of various and contradictory CISs, which worked as relatively predictable ‘scene’-dependent selves or unpredictable both-neither, ‘slippery’ selves. At the same time, they confessed to experiencing inauthenticity, wrongness, abnormality, guilt, and shame, stemming from the over-psychologised concept of an ‘authentic’ self, which is assumed to be by default highly coherent and stable. Their primary needs were: (i) to understand why the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ could not be simple and ‘untwisted’, and why their multiple, situational, and ‘slippery’ selves were neither immoral nor pathological, nor simple effects of the too easily blamed bad parenting, but rather products of very complex socio-cultural dynamics; (ii) to allow each part of their multiple-self to speak loudly; (iii) to make their multiple-self-conversations move from fogginess to clarity. Thereafter, they needed to become aware of (iv) which part of their multiple-self was speaking on behalf of which CIS; (v) the fact that, through their choices, they were effectively participating in social dynamics, feeding either their desired or undesired CISs; (vi) the fact that they had to choose a social world and a corresponding self, rather than just a practical, neutral solution to their problem/goal.

In DSC contexts, the challenge for coaches is to help people better understand what is really at stake beyond the narrow and short-term personal and/or organisational goals. It is not just about punctual solutions and performances, and coping with or adapting to change. It is about participation in co-constructing ongoing social and cultural change or reproduction. The coach’s role is not to decide what is desirable or undesirable for the coachee but instead to ensure that they do not act as blind accomplices to undesirable CISs dynamics.

Learning-to-develop through research design

There is no consensus on how coaching, learning, and development relate to each other. Some consider that ‘adult learning’ and ‘adult development’ are distinct approaches to coaching (Ives, 2008), suggesting that not all coaching would be a learning activity leading to development. In contrast, Bachkirova et al. (2014, p. xxxiv) explicitly state that learning ‘underpins all coaching practice’, instead of being a standalone approach, and many others analysed coaching as a process of adult learning and development (see summaries in Bennett and Campone, 2017, and Lawrence, 2017). I could not see how any change in the coachee’ ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—essential for creating and implementing sustainable alternative solutions and achieving ambitious goals—would be possible without learning and development. Consequently, I subsumed my coaching under the ‘learning-to-develop social activities’ category, at the intersection of self-directed learning (Knowles, 1975), experiential learning (Kolb, 2015), critical pedagogy (recently referred to as a source of coaching in Shoukry, 2017), transformative learning (Mezirow, 1991), and expansive learning (Engeström, 2015). Learning-to-develop refers to deliberate learning directed towards a desired, intended development, be it at the individual, organisational, community, or societal levels. I prefer ‘learning-to-develop’ to the usual ‘learning and development’ (L&D) because ‘and’ suggests separate processes, whereas ‘to’ emphasises that learning is a precondition for development; moreover, desired development requires the deliberate action of social actors, and the verb ‘to develop’ rather than the noun ‘development’ emphasises their agency. Below, I argue for a learning-to-develop through research (LDR) model of coaching, based on the assumption that, in DSC contexts, there is no expert in the coach–coachee partnership. As ‘classic’ approaches assume, the coach is not an expert—unlike a counsellor, a mentor or a professor. But neither is the coachee. Relevant knowledge must be constructed during the coaching process. This means that the coaching process is actually a research process. Research does not just provide evidence to inform professional practice; it is its very essence.

My first argument is that objective ignorance is higher than ever in today’s DSC contexts. As elucidated above, the coachee’s knowledge, experience, and self-awareness may no longer be as useful, rewarding, and empowering as in more stable contexts. People now inevitably discover more of their ‘weaknesses’ than ‘strengths’. No one, except perhaps individuals in isolated communities, can accurately predict what their social worlds and roles-identities-selves will be like in a few years or even months, and what appears to be a ‘strength’ today may prove a ‘weakness’ in the near future. Individuals’ identities, values, goals, objectives, effective solutions, and means are no longer ‘facts [to be acquired] from within’ (Whitmore, 2009: 9-10). They are, instead, works in progress, much like the CISs. Thorough self-reconstruction, intertwined with societal, organisational, and group reconstruction, are unavoidable pillars for the coaching process to act as an ‘enabler for [desirable social] change’.

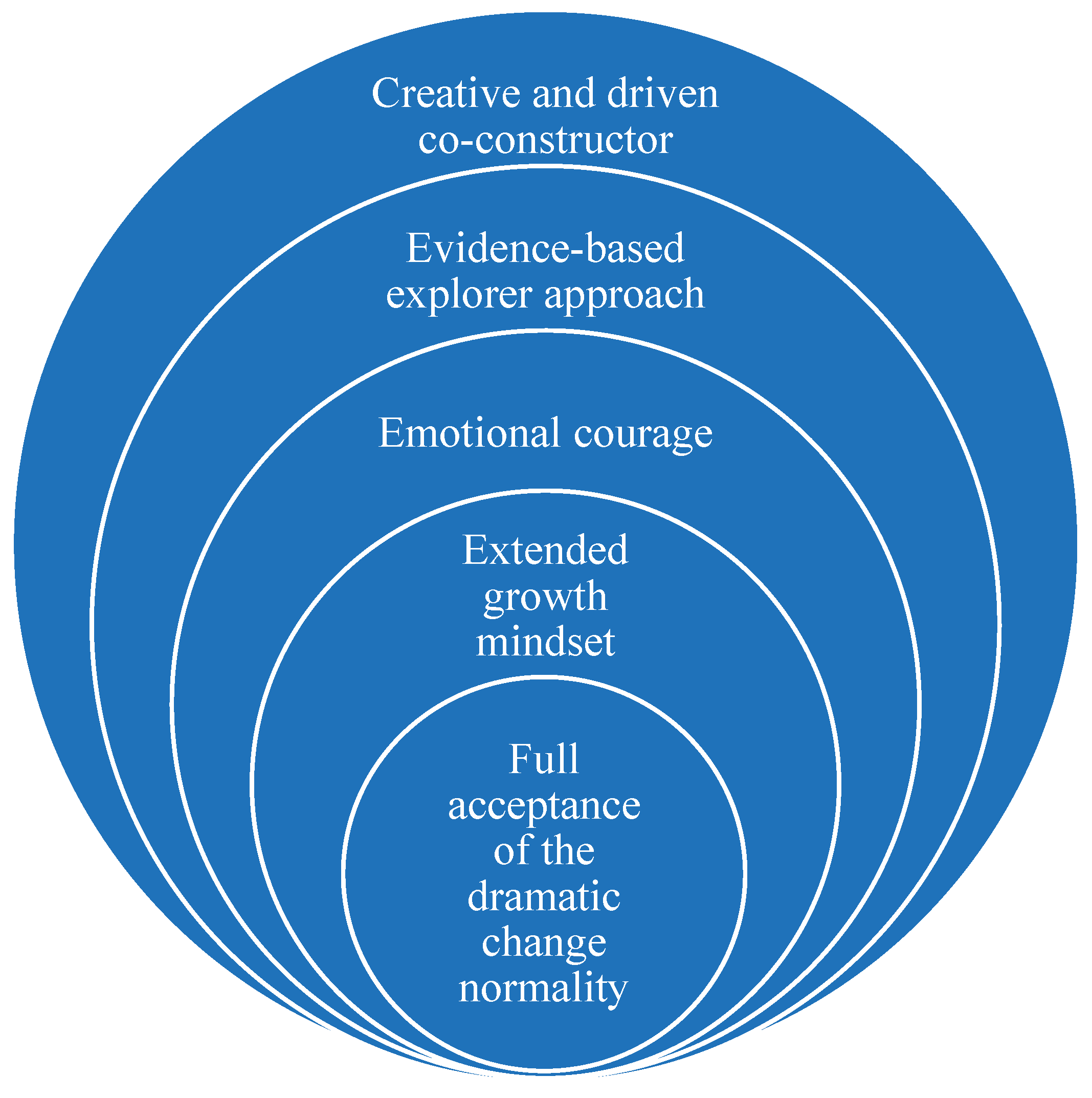

In DSC contexts, the key assets are as follows: (i) the

acceptance of DSC as normal—it is now a pervasive and persistent reality and no longer a temporary ‘crisis’; (ii) an

expanded growth mindset (Dweck, 2017) that can be condensed into ‘let us explore and discover what we can become better at, and how much better at, whatever it is we want or need to be’; (iii)

emotional courage, that is, the de-pathologising of the so-called ‘negative emotions’, which should be placed at the heart of emotional intelligence theories and programmes (‘If You Are Willing to Feel Everything, You Can Do Anything’; Bregman, 2018); (iv) an

evidence-based mindset of an explorer in an unfamiliar territory, who has initiative, ownership, and autonomy; curiously and carefully observes things; produces hypotheses regarding the consequences of their actions in the given context; tests and re-tests hypotheses against facts; capitalises upon the experience; and expands upon what they have capitalised by incorporating it into a larger and open-to-change picture; and (v) the

spirit of cooperation, determination, and creative freedom among those taking action to build, for instance, a more functional and beautiful city after a disaster (

Figure 2).

The second argument points to Socrates’ maieutic, which is often referred to by coaches defining coaching as

a Socratic based future focused dialogue between a facilitator (coach) and a participant (coachee/ client), where the facilitator uses open questions, summarises and reflections which are aimed at stimulating the self-awareness and personal responsibility of the participant (Passmore & Dromantaite, 2020, p. 561; emphasis in original).

According to Plato (1992), Socrates used the metaphor of a midwife giving birth to a child to explain his dialogic process. This is misleading if one ignores the fact that it may have been Socrates’ self-defence against the allegations that led to his execution, and if one does not explore how the conversation actually takes place in ‘Dialogues’, e.g. in ‘Charmides’ (Plato, 2019), which is most relevant to coaching. As illustrated in this dialogue, the maieutic is not simply a process of giving birth to knowledge ‘from within’ as if it were already there but rather a collaborative search-research-construction process, stemming from an agreed-upon question and the answers expressed by Socrates’ interlocutor (‘the coachee’). Socrates (‘the coach’) had a clear symbolic authority (i.e. recognised power based on his reputation). However, he exerted it using three key tools. First, he encouraged a non-formal relationship of mutual strengths-recognition, admiration, trust, and respect with ‘the coachee’ and repeatedly fed this relationship. Second, he nurtured an assumption of equal ignorance of all the interlocutors regarding the answer being sought. Third, he took any answer as a hypothesis to be questioned. The dialogue progressed through persistent open-ended questioning, repeated reminders of the ignorance assumption, and progressive meaning-making, with both participants co-constructing hypothetical answers and exploring whether they are internally consistent, consistent with the other’s views, and consistent with the facts. ‘The coachee’ contributed personal queries, beliefs, knowledge, and reflections. ‘The coach’ contributed paraphrases, questions, summaries and, with the coachee’s permission, personal reflections, beliefs, experiences, and knowledge. They develop cooperation without consensus: they generate shared language and listen attentively to understand each other's perspective, but no one tries to impose a truth, and everyone respects their right to make their own choices. According to De Dominicis and Stelter (2023: 25), contemporary coaching has reached this symbiosis in the Third Generation: ‘coach and coachee are collaborative partners in the dialogue as it naturally unfolds, and share their experiences, considerations, and reflections in a symmetrical and resonating partnership’.

The third argument is that the best Socratic conversation is a necessary yet not sufficient condition for coaching effectiveness. Defining coaching simply as a ‘dialogue’ or ‘conversation’ overlooks the fact that it comprises both meaning-making and mental transformation of the experience and testing the new meanings against real-life contexts. Effective coaching combines both (self) conversational and practical real-life-action-by-the-coachee phases iteratively. Overlooking the second to focus on conversation, as many definitions and models do, may significantly reduce coaching effectiveness.

The fourth argument is that the competencies required to become a coach (Association for Coaching, 2012; ICF, 2019b; Passmore, 2020) have naturally—and seemingly without awareness—moved towards incorporating some of the attitudes and skills common to qualitative research: a genuinely curious attitude; building and maintaining trust; a respectful relationship; confidentiality and informed consent; an empathic, non-judgmental, and encouraging presence; non-violent communication; managing life-story sequences; silence; mindful listening and observation; open-ended questions; summaries, rewording, reframing, affirmations, and reflections; discerning between perceptions/opinions and facts; evaluating beliefs and interpretations against facts; scaling; identifying patterns; taking notes; and engaging in reflective practice. Toyota Kata, developed synchronously with LDR coaching, explicitly states: ‘Scientific thinking may be the best way we have of navigating through unpredictable territory to achieve challenging goals’ (Rother, 2018: 1; emphasis added). However, coaches do not systematically learn scientific thinking in their training programmes. They are advised to incorporate research findings into their practice (Grant et al., 2010; Jones, 2020), which is different from having a clear awareness of the similarity between coaching and research as processes, and between coaches’ and researchers’ competencies.

I suggest that a research toolkit for coaches (researcher’s mindset, scientific thinking, and research methodology) must be developed, carefully learned in training, mentoring, and supervision, and tested as part of the certification process. The greatest advantage of coaching and its clear difference from psychotherapy, counselling, mentorship, training, and teaching is that any programme can and, at least in today’s DSC contexts, should be designed as a tailor-made, evidence-based, exploratory process. Coaching differs from standard research in that its main purpose is not to produce generalisable knowledge, rather to elicit the knowledge that is necessary and sufficient for deliberate learning, leading to the achievement of the coachee’s specific goals and the development they desire in themselves and their social worlds. Compared to standard evidence-based experiments, this is a ‘loose’ understanding of evidence-based research. For the coachee’s goals to be selected and achieved in a DSC context, optimal, standardised evidence-based research remains important; however, this is not primarily because of its findings’ validity and reliability since they have a high probability of being proven invalid in the case of a coachee’s specific goal in a specific DSC context. Instead, it is important because it provides (i) the most appropriate mindset for both the coach and the coachee (the ignorance assumption combined with gnoseological optimism, the explorer’s curiosity and sense of presence, persistent inquiry resulting in hypotheses, and testing-retesting hypotheses against facts); (ii) methodological steps, tools, and skills for the process; and (iii) certain findings that both the coach and coachee must regard just as possible pieces for the jigsaw puzzle that the coachee creates and tests-retests.

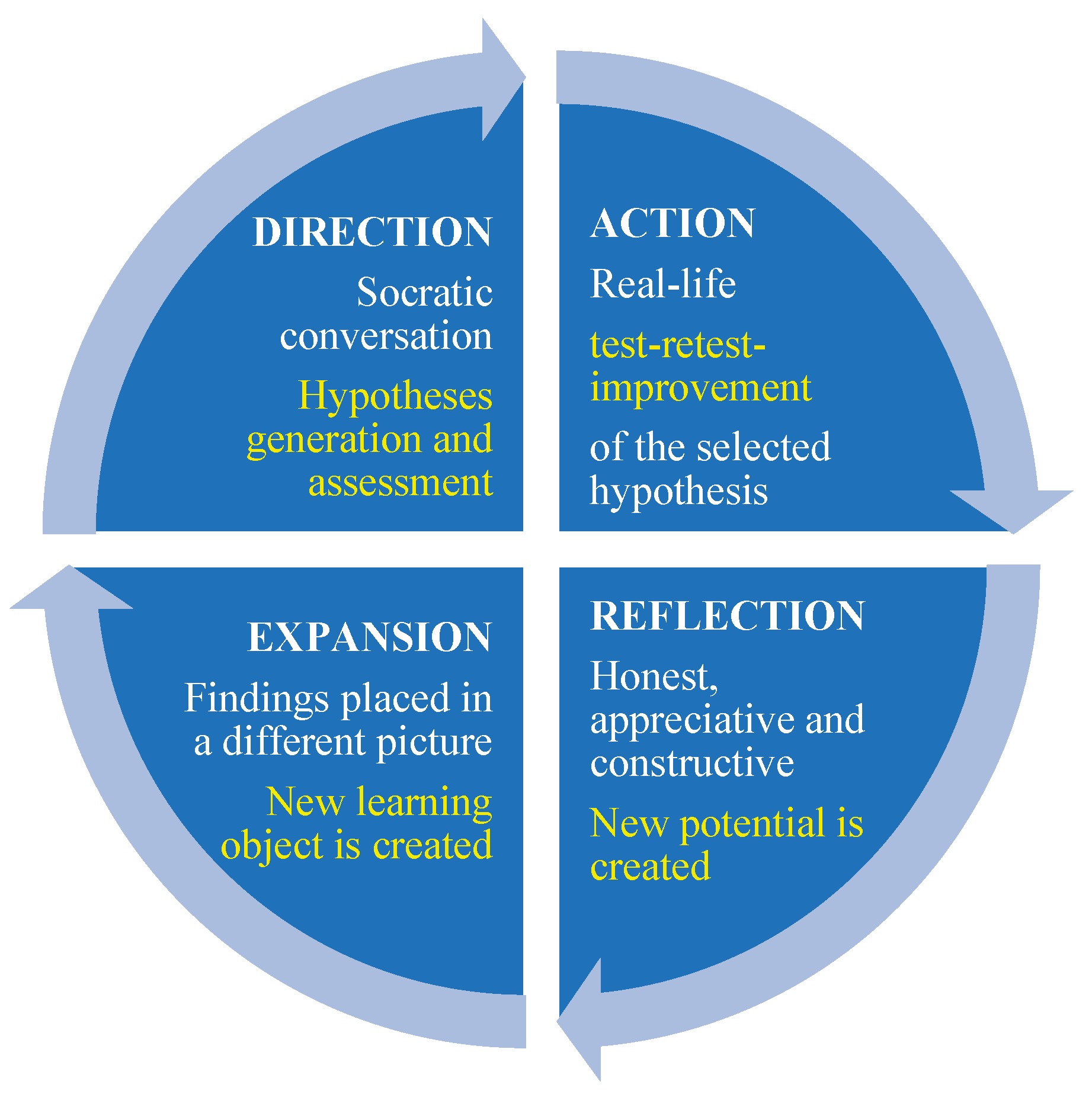

As it has evolved over my 14 years of reflective practice, the LDR model of coaching works as an expanding spiral of iterative cycles in four

flexibly sequenced phases (DARE;

Figure 3):

- (i)

-

Direction. The core questions ‘What do you want to leave this programme/session with?’ and ‘Why and for what?’ are answered. The coachee’s narrative is explored through Socratic conversations to develop a shared understanding of the desired future among several versions being questioned, the discrepancy between the actual and desired situation, and the necessary learning content. Hypothetical answers to specific ‘who, with whom, what, why, how, when and where’ are framed. Expected consequences are pondered. The process is both different from and similar to anticipatory action-learning. It is different in that there is no ‘programmed knowledge’ to be learned; instead, the necessary learning content is to be discovered/created. And it is similar in that

the future itself is challenged, and thereby recreated. […] the exploration of possible (the full range of agency and imagination), probable (likely given historical structures) and preferred (where we seek to go) futures. […] As important as the social construction of the future is the ownership of the future created. […] It is not just liberation from conventional and used futures but also from the intellect that creates this questioning (Inayatullah, 2006: 657; 658; 659)

- (ii)

Action by the coachee in their real life. One selected hypothesis a day is tested-retested. The coachees integrate a hypothetical answer—instead of ‘applying’ or ‘implementing’ a solution or plan of action—of their choice into their ordinary activities and observe whether the consequences are as predicted/wanted.

- (iii)

Reflection on the experience of testing-retesting is done, both self-directed and guided by the coach, to explore, capture, and record what has proven effective and to generate new hypotheses.

- (iv)

Expansion. What has been recorded as effective is used to create a new mental model of the action, according to the desired social worlds and selves, which is then tested-retested repeatedly in various areas of life and contexts, until it is incorporated/learned—that is, the desired behaviour occurs naturally in various situations.

The idea of developing hypotheses, integrating and testing them into the coachee's ordinary agenda at their own choice and pace, observing the consequences, performing reflections, and creating new open and dynamic mosaics/kaleidoscopes of action helps overcome resistance and fear of failure, unleash creativity, increase confidence and motivation, and move towards the desired results. Therefore, it is highly and realistically empowering.

The first three phases create a new potential for the coachee and for the social world in which they are primarily pursuing their goals. In the fourth phase, a new learning object (model of action) is created, trained, and expanded to other relevant social worlds. The process differs from the typical coaching process which follows SMART objectives, explicitly agreed upon by coach and coachee (and sponsor, if applicable). In contrast, LDR coaching—which works according to this principle: ‘Let us, coach and coachee, be open and curious to explore what you can build better in yourself, your social worlds, and your society’—seeks desirable results that cannot be thought, contracted, and planned at the beginning. Such results are often more realistic or ambitious than the goals the coachees can imagine when entering the process. The coachee’s initial desires and goals only provide the entry into the process, the main field of research and learning, and tangible short-term accountability. Individual flourishing, an outcome sought in some types of coaching, develops progressively as a natural consequence rather than being a goal in itself.

The coach assumes a quasi-researcher role and guides the coachee to do the following: articulate, clarify, and organise their wishes, perceptions, interpretations, emotions, and knowledge; distinguish between knowledge and beliefs and between data/descriptions and interpretation/judgement; evaluate everything against facts; identify the needs to be fulfilled and articulate appropriate and sustainable solutions; become aware of moments and sources of doubt, discouragement, and resistance; and discover and activate the available internal and external resources to proceed further. Moreover, the coach works as a participant-observer during the conversation, honestly sharing their observations and providing alternative mental models of reality (not definitive solutions) as possible pieces for the open kaleidoscope being created by the coachee. The process remains facilitative instead of authoritarian: coachees consciously decide whether and how to integrate the jigsaw pieces provided by the quasi-researcher coach (not expert in the given issues) into their multiple-self-conversations and real-life actions, taking responsibility for their actions and inactions and the corresponding consequences; they also work to clarify their specific needs and desires; outline their goals and outcomes; seek their own alternative actions and test-retest the selected ones in their real-life contexts; act as participant observers, collecting the raw field data needed to build grounded evaluations and improved solutions; evaluate the results; and exercise power at each stage of the process.

The programme usually lasts a year, with 12–15 sessions at increasingly spaced intervals, which can be changed according to the coachee’s goals, needs, and choices. After programme completion, two feedforward sessions per year are recommended, and several beneficiaries call for them. A typical programme explores the coachee’s feelings and desires in six interrelated areas of life: self (health, awareness, and management); family (parents and siblings, couple, and children); work, money, and hobbies; social capital (efficient networks of relations) and community capital (nature, culture, services, and institutions); social involvement-responsibility; and deliberate learning. This holistic, integrated approach prevents the coaching process from being hijacked by ‘hidden agendas’ and facilitates the aggregation of a wide range of resources to support the coachee’s goals. It also prevents progress in one area alone leading to rampant imbalances in other areas. Three core values and work directions are discussed and agreed upon: competency-based performance, integrity, and balance. The assessment of effectiveness addresses the coachee’s specific goals and the areas and values specified above. This assessment is carried out using the following procedures and tools: (i) direct feedback from the beneficiary at the end of each session; (ii) the coach’ extensive reflection on their own practice, based on specific ‘field notes’ and the study of relevant literature after each session; (iii) a semi-structured follow-up questionnaire completed by the coachee three days after each session; (iv) three monitoring sessions—after 3, 6, and 12 months from the start of the programme; and (v) a semi-structured questionnaire using subjective and objective measures that helps the coachee summarise the positive and negative changes in the six areas of life, their causal attributions in relation to the programme, their focus forward, and suggestions for the coach to increase the programme’s effectiveness. Writing these documents is recommended as a learning tool to increase awareness, confidence, and motivation and gain further direction, and many coachees send them to me. A wide range of valued outcomes in all six areas of life have been reported, as well as some undesired effects, but this topic is beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusion: New mission and definition for coaching to address DSC

This paper argues that the potential and complexity of coaching and the social responsibility of coaches are significantly greater than generally assumed. It reveals how coaching in DSC contexts naturally and inevitably participates in the joint reconstruction of the self, social worlds, and society and how, by ignoring this, coaches can make coaching a tool for undesirable social dynamics. It proposes new directions for developing coaching approaches and models to address DSC. Specifically, it argues that coaching is not just about helping people perform better or cope with and adapt to change—issues also addressed in counselling, psychotherapy, training, and mentoring. Rather, it is about helping them to realise their own projects by consciously participating in the ongoing construction of change in their social worlds, societies and their corresponding roles-identities-selves. Thus, coaching and coaches have a clear, legitimate, and up-to-date place and social role that can no longer be confused with those of other related occupations and professionals. A new definition of coaching can be inferred from the observations and analyses elucidated here. It has two dimensions: social activity and process.

First, I define coaching as a deliberate, tailor-made, multi- and inter-disciplinary learning-to-develop social activity. Its purpose is to make the problematic relationship between individuals and their complex and dramatically changing worlds more competent and sustainable. Thus, it helps individuals better understand their social worlds’ complexity and dynamics, discover the corresponding complexity and dynamics of their multiple and changing social roles-identities-selves in this context, understand the participation of their daily practices in the simultaneous (re)construction of their roles-identities-selves and social worlds, make better-informed choices regarding specific goals, solutions, and means to sustainably increase life-chances, and act more efficiently and sustainably in pursuing their respective plans. The value of coaching as a learning-to-develop social activity is optimally revealed both by its short-term results and, especially, by the future it opens up for the individual, its relevant social worlds, and society.

Second, I define coaching as an open-anticipative LDR process that comprises four expansive spiral iterative phases: (i) Socratic conversations between a beneficiary (coachee) and a professional (coach), that uncover, reframe, enrich, and organise the coachee’s multiple-self-conversations and generate and assess hypothetical answers; (ii) the coachee’s real-life actions for testing-retesting their selected hypothetical answers; (iii) guided reflections to capitalise upon the experiences to highlight the new potential; and (iv) the expansion of what has been capitalised to create new learning objects and make learning effective.

The article makes clear that there is a self-serving bias in Grant et al.’s (2010: 125) advocacy of coaching psychology: ‘While psychologists’ training would appear to ideally equip them for the delivery of coaching services, psychologists have not been seen as uniquely qualified coaching practitioners; either within the coaching industry or by the purchasers of coaching services’ (emphasis added). Psychologists are not ideally equipped for coaching in today’s world of DSC, except when it is used as ‘a substitute for counselling or psychotherapy as some clients find coaching more attractive’ (Palmer and Whybrow, 2008: 136) or as ‘an intervention to address subclinical issues’ (Dromantaite and Passmore, 2020: 561). Moreover, no other single-disciplinary professionals are ‘ideally equipped’ for coaching to address DSC. A pressing need exists to change the paradigm and create, test, and promote new ecological, multi- and inter-disciplinary coaching approaches and models that begin with the big picture of human society in its natural environment rather than merely attaching particular sociological conceptualisations to the existing individual- or organisation-centred models. Certainly, there is a wealth of pre-existing puzzle pieces that can be ‘recycled’, and coaching psychology and other existing approaches and models are great pools of resources for the new approaches and models. If properly developed and adopted by a significant number of coaches, such approaches and models may better ‘bridge the human gap’, which was first defined in 1979 as

…dichotomy between a growing complexity of our own making and a lagging development of our own capacities. […] it is not only our capacity to cope with which is in question but also our ability or willingness to perceive, understand, and take action on present issues as well as to foresee, avert, and take responsibility for future ones. (Botkin et al., 2014: 6–7; emphasis added)

The rationale and key features of a psycho-sociological approach and an LDR model have been described above. From a psychological viewpoint, it uses an eclectic human needs-based emotional-cognitive-behavioural approach; the closest ‘relative’ in coaching psychology is SPACE (Edgerton and Palmer, 2022). I consider it a work-in-progress subject to further criticism, enrichment, and transformation.

Questions can be raised regarding the specifics of its workings and how specifically self-directed, experiential, critical, transformative and expansive learning are related. Furthermore, systematic research on the model’s effectiveness is needed. These are limits of this paper and also topics for future work. Additionally, research is necessary to see how the proposed approach and model could be taught/learned and made effective when provided by others, in different socio-cultural contexts. This work is currently underway. Six people based in Romania, Italy, and Spain are in training and have recently started providing LDR coaching under my guidance and supervision.

Other emerging directions for interdisciplinary research are also worth highlighting. First, there is a growing need for empirical research on how coaching—beyond good intentions and, sometimes, naïve assumptions and questions—relates to societal and global issues such as manipulation, social stratifications and inequality, social mobility, social responsibility, corruption, criminality, depletion of natural resources, climate change, and so on. Second, a sensitive research topic concerns the hyper-psychologisation of coaching practices, which could narrow individuals’ cognitive focus, perceptions, and interpretations; encourage egocentric, voluntaristic expectations and behaviours; weaken social bonds; increase alienation and vulnerability; and contribute to undesirable social dynamics. This concept has only been proposed and lightly drawn; if adopted as a research subject, it would need proper operationalisation. Third, the observations about the multiple dialogical selves suggest that contemporary DSC contexts may challenge the current research on the consistency, stability and changeability of personality traits (Bleidorn et al., 2022; Wright and Jackson, 2023). Fourth, research on whether and how pro-bono coaching could realistically increase the agency, autonomy, and social responsibility of coachees should be conducted.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

It is not possible to share the qualitative data used in writing this paper for ethical reasons (they are not anonymous).

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to her recently established team of coaches. They have given meaning to the writing of this paper and provided emotional support, as well as helped with the efficient documentation of some ideas and in critically reviewing the manuscript: Claudia Clicinschi, Diana Alexandru, Lavinia Dieac, Mihaela Anghel, Natalia Țetcu, and Ramona Chivu. She is also grateful to Professor Mihai Dinu Gheorghiu from `Alexandru Ioan Cuza` University Iasi, Romania, who accepted to read the manuscript and gave useful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Association for Coaching (2012) AC Coaching Competency Framework. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.associationforcoaching.com/resource/resmgr/Accreditation/Accred_General/Coaching_Competency_Framewor.pdf (accessed 2 November 2023).

- Bachkirova T, Cox E, and Clutterbuck D (2014) Introduction. In: Cox E, Bachkirova T and Clutterbuck D (eds) The Complete Handbook of Coaching. 3rd ed. London: Sage, pp.xxix–xlvii.

- Bennett JL and Campone F (2017) Coaching and theories of learning. In: Bachkirova T, Spence G and Drake D (eds), The Sage Handbook of Coaching. London: Sage, pp.102–120.

- Bennett N and Lemoine GJ (2014) What VUCA really means for you. Harvard Business Review 92: 27–42.

- Berger PL and Luckmann T (1967) The Social Construction of Reality. A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: The Penguin Press (original work published 1966).

- Bidisha LD and Mukulesh B (2013) Employee Retention: A Review of Literature. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 14: 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn W, Schwaba T, Zheng A et al. (2022) Personality stability and change: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin 148(7-8): 588–619. [CrossRef]

- Botkin JW, Elmandjra M, and Malitza M (2014) No Limits to Learning: Bridging the Human Gap: The Report to the Club of Rome. Oxford: Pergamon (original work published 1979).

- Bourdieu P (1987) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (original work published 1979).

- Bowen GA (2006) Grounded theory and sensitising concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(3): 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis RE, Hullinger A, Ehasz SF et al. (2022) The grand challenge for research on the future of coaching. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 58(2): 202–222. [CrossRef]