Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

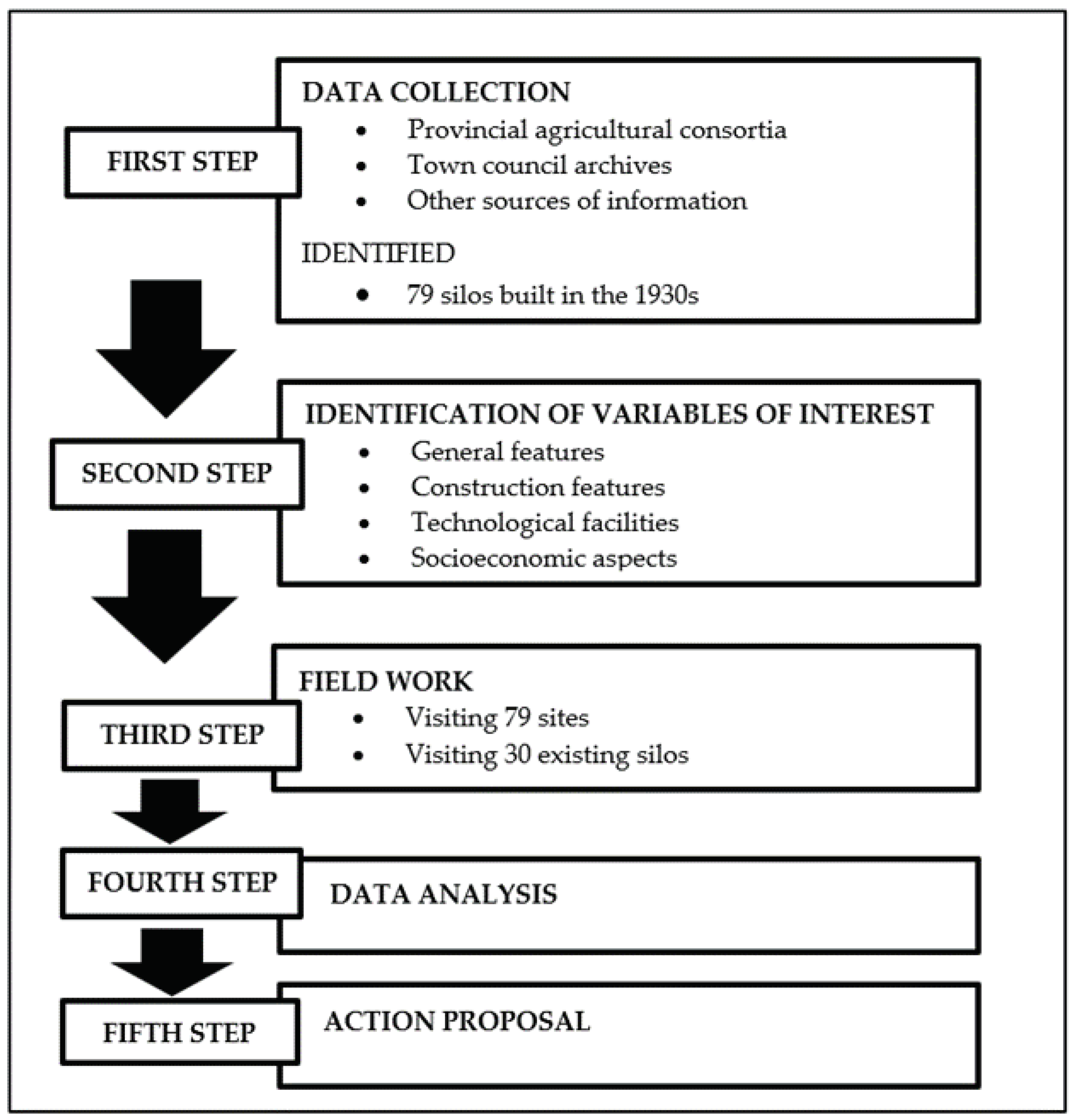

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- General features:

- ○

- Location (region, province, and town);

- ○

- Geolocation (coordinates ETRS 89 Use 32-33);

- ○

- Year when built;

- ○

- Ownership (agricultural consortium, private company, municipality, or foundation);

- ○

- Use (grain store, disused, or reused);

- ○

- State of conservation. (1) Good condition: The silo is in good condition, i.e., it has no significant construction defects. (2) Fair condition: The silo is leaky, it has water in the basement, its electric wiring has been burgled, its perimeter fencing is broken, etc. (3) Unusable: The silo is badly damaged or in ruins. (4) Under refurbishment: the silo is in the process of being refurbished. (5) Refurbished building.

- 2.

- Construction features:

- ○

- Type (vertical-cell silo, silo with ground floor and sloping first floor, or silo with floors);

- ○

- Storage capacity (t);

- ○

- Height (m);

- ○

- Ground plan (square or rectangular);

- ○

- Roof shape (flat roof, gable roof, flat tower roof and gable roof over the rest, or sawtooth roof);

- ○

- Tower position (central tower flush with the silo, eccentric tower flush with the silo, frontal tower, or frontal tower sandwiched between two cells or offices) (Figure 3);

- ○

- Number of storage cells;

- ○

- Number of rows of cells;

- ○

- Number of cells per row;

- ○

- Cell shape (circular or square);

- ○

- Cell height (m);

- ○

- Cell row position (cells raised off ground floor, cells resting directly on flooring of each storage floor).

- 3.

- Technological facilities:

- ○

- Number of elevators;

- ○

- Number of upper-storey horizontal conveyors;

- ○

- Number of lower-storey horizontal conveyors;

- ○

- Existence of dust vacuum system (yes or no);

- ○

- Existence of grain-cleaning machinery (yes or no);

- ○

- Existence of lift (yes or no);

- ○

- Existence of railway (yes or no).

- 4.

- Socioeconomic aspects:

- ○

- Population;

- ○

- Demographic patterns;

- ○

- Yearly municipal budget (€);

- ○

- Economic activity;

- ○

- Land communications;

- ○

- Distances to larger urban centres (km).

| Categories | Variables of interest |

|---|---|

| General features | Region |

| District | |

| Town | |

| Geolocation Year when built Ownership Use State of conservation | |

| Construction features | Type |

| Storage capacity (t) | |

| Height (m) Ground plan | |

| Roof shape | |

| Tower position | |

| No. storage cells | |

| No. rows of cells | |

| No. cells per row | |

| Cell shape Cell height (m) Cell row position | |

| Technological facilities | No. elevators |

| No. upper-storey horizontal conveyors | |

| No. lower-storey horizontal conveyors Existence of dust vacuum system Existence of grain-cleaning machinery Existence of grain-cleaning machinery Existence of lift Existence of railway | |

| Socioeconomic aspects | Population Demographic patterns |

| Yearly municipal budget (€) | |

| Economic activity | |

| Land communications | |

| Distances to larger urban centres (km) | |

3. Results and Discussion

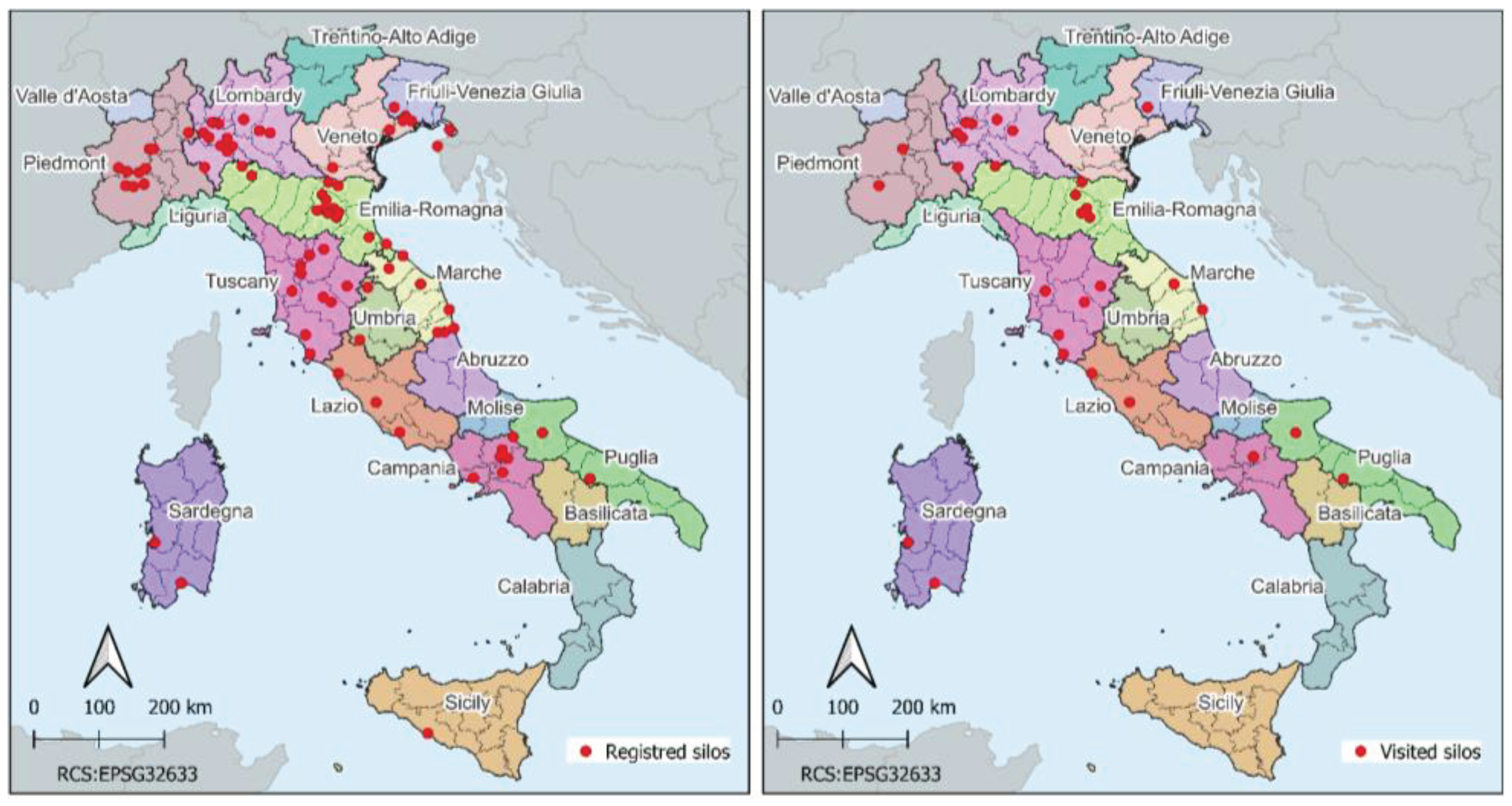

3.1. The ammasso silos

3.2. General Features

| Category | Total | Min. | Max. | Mean | Silo distribution in percentages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 10 | 23.3% Lombardy; 20.0% Emilia Romagna; 16.7% Tuscany; 6.7% Lazio; 6.7% Marche; 6.7% Piedmont; 6.7% Puglia; 6.7% Sardinia; 3.3% Campania; 3.3% Friuli Venezia Giulia. | |||

| Province | 24 | 13.3% Bologna; 10.0% Milan; 6.7% Grosseto; 3.3% each in all remaining provinces with silos. | |||

| Town | 30 | ||||

| Year when built | 1923 | 1939 | 1936 | ||

| Ownership | 70.0% agricultural consortium; 22.2% private company; 16.7% municipality; 11.1% foundation. | ||||

| Use | 53.3% disused; 26.7% reused; 20.0% grain store. | ||||

| State of conservation | 17.6 % good condition; 11.8 % fair condition; 32.4 % unusable; 11.8 % in process of refurbishment; 14.7% refurbished; 11.8% demolished | ||||

| Type | 3 | 53.3% basement, ground floor, and two to five additional storeys; 30.0% vertical cells; 16.7% ground floor and first floor with sloping floor. | |||

| Capacity (t ) | 200,000 | 1,900 | 40,000 | 6,670 | |

| Height (m) | 16 | 40 | 22.7 | ||

| Ground plan | 100.0% rectangular | ||||

| Roof shape | 43.3% flat roof; 23.3% flat tower roof and gable roof over the rest; 20.0% gable roof; 13.3% sawtooth roof. | ||||

| Tower position | 46.7% frontal tower between two cells or offices; 33.3% frontal tower; 16.7% central tower flush with the building; 3.3% eccentric tower flush with the building. | ||||

| No. storage cells | 15 | 640 | 91 | ||

| No. rows of cells | 2 | 24 | 4 | ||

| No. cells per row | 4 | 36 | 7 | ||

| Cell shape | 80.8 % square; 20.0% rectangular. | ||||

| Cell height | 4 | 20 | 5.8 | ||

| Cell row position | 73.3% cells resting directly on flooring of each storage floor; 26.7% cells raised off flooring of ground floor. | ||||

| No. elevators | 1 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| No. upper-storey horizontal conveyors | 1 | 6 | 1.5 | ||

| No. lower-storey horizontal conveyors | 1 | 6 | 1.8 | ||

| Dust vacuum system | 86.7% yes; 13.3% no. | ||||

| Grain-cleaning machinery | 80.0% yes; 20.0% no. | ||||

| Lift | 93.3% no; 6.7% yes. | ||||

| Railway | 73.3% no; 26.7% yes. |

3.3. Layout and construction characteristics

3.4. Technological facilities

3.5. Socioeconomic aspects and reuse possibilities

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teague, W.D. Flour for Man’s Bread: A History of Milling; Minnesota Archive Editions: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, P.L. La controversa storia della Porticus Aemilia. Archeologia Classica 2012, 63, 575–591. https://www.academia.edu/2209356/La_controversa_storia_della_Porticus_Aemilia.

- Banham, R. A Concrete Atlantis. US Building and European Modern Architecture; MIT Press: Massachusetts, U.S, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Salido, J. El almacenamiento de cereal en los establecimientos rurales hispanorromanos. In Horrea d'Hispanie et de la méditerranée romaine; Arce., J., Goffaux, B., Eds.; Casa Velazquez: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.V. Catalogación de las unidades de almacenamiento vertical de cereales de la red básica de Castilla y León, propuesta de una nueva clasificación y posibilidades de reutilización. Level of Thesis, Universidad de león, León, Spain, 29 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Lopes, P.; Mateo, C.; Landi, S. La historia y fundamentos de la construcción de la Red Nacional de Silos mediante un análisis comparativo entre España, Italia y Portugal. In Proceedings of the XII congreso nacional y IV congreso internacional hispanoamericano de Historia de la construcción, Mieres, Spain, 4 - 8 october 2022; pp. 381–393. [Google Scholar]

- Profumieri, P. L. La Battaglia del grano: costi e ricavi. Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, 1971, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Preti, D. La política agraria del fascismo: note introduttive. Studi Storici, núm. 4. In Le Campagne Emiliane in periodo fascista. Materiali e Ricerche sulla Battaglia del Grano. Annale n.º 2, 1981-1982; Legnani, M., Preti, D., Rochat, G., Eds.; CLUEB: Istituto Regionale per la Storia della Resistenza e della Guerra de Liberazione in Emilia Romagna: Bologna, Italy, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Preti, D. Per una storia agraria e del malessere agrario nell’Italia fascista: la battaglia del grano. In Le Campagne Emiliane in periodo fascista. Materiali e Ricerche sulla Battaglia del Grano. Annale n.º 2, 1981-1982; Legnani, M., Preti, D., Rochat, G., Eds.; CLUEB: Istituto Regionale per la Storia della Resistenza e della Guerra de Liberazione in Emilia Romagna: Bologna, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- D’Attorre, P. P. Non di solo pane. Gli agrari bolognesi e la battaglia del grano. In Le Campagne Emiliane in periodo fascista. Materiali e Ricerche sulla Battaglia del Grano. Annale n.º 2, 1981-1982; Legnani, M., Preti, D., Rochat, G., Eds.; CLUEB: Istituto Regionale per la Storia della Resistenza e della Guerra de Liberazione in Emilia Romagna, Bologna, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, L. La battaglia del grano. Depressione economica e política cerealicola fascista; CUEM: Milano, Italy, 1984; pp. 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, J.; Castelló, J.E.; Forcadell, C.; Izuzquiza, I.; García, Mª.C.; Loste, Mª.A. Historia del Mundo Contemporáneo; Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 1996; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Barciela, Carlos. Ni un español sin pan. La red nacional de silos y graneros, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain. 2007.

- Vaquero, M. I silos granari in Italia negli anni Trenta: fra architettura e autarchia económica. Pratimonio Industriale 2011a, 7, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero, M. Innovation in times of autarky: the construction of the wheat silos in Fascist Italy. Fabrikart 2011b, 10, 264–277. [Google Scholar]

- GU, 1934. Regio Decreto de 21 maggio 1934, n. 821, disposizioni complementari al Regio Decreto Legge 10 giugno 1931, n. 723, concernente l'obbligatorieta' dell'impiego di una determinata percentuale di grano. Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 87 del 6 giugno 1924.

- GU, 1935 Regio Decreto Legge 4 luglio 1925, n. 1181, Istituzione di un Comitato permanente per il grano. Gazzetta Ufficiale n.165 del 18 luglio 1925.

- GU, 1936a Regio Decreto Legge 16 marzo 1936, n. 392, disciplina del mercato granario. Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 65 del 18 marzo 1936.

- GU, 1936b. Regio Decreto Legge 15 giugno 1936, n. 1273, disciplina del mercato granario. Gazzetta Ufficiale n.155 del 7 luglio 1936.

- BOE. Decreto Ley de 23 de agosto de 1937, de ordenación triguera. Boletín Oficial del Estado 25/08/1937: 3025-3028. Available online: https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE//1937/309/A03025-03028.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Fernández-Fernández, MV, Marcelo, V, Valenciano, JB, and González-Fernández, AB. Characterisation of the National Network of Silos and Granaries in Castilla y León, Spain: A Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcárate, C.A. Catedrales Olvidadas. La Red Nacional de Silos en España 1949-1990; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino, Madrid, Spain, 2009.

- Alves, J.A. Arquiteturas do Trigo: Espaços de Silagem no Alentejo, do século XIX à atualidade. Degree in architecture, University Évora, Portugal. 22/12/2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10174/19745 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Amaral, L. Política e economia: O Estado Novo, os latifundiários alentejanos e os antecedentes da EPAC. Analise Social 1996, 31, 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bornás, G. El hombre, la explotación, el mercado: organización de la economía agrícola dirigida en Alemania; Gráficas Afrodisio Aguado: Madrid, Spain, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Corni, G. La politica agraria del nazionalsocialismo (1930-1939); Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, F.; De Falco, A.; Landi, S.; Bevilacqua, M.G.; Santini, L.; Pecori, S. Reusing grain silos from the 1930s in Italy. A multi-criteria decision analysis for the case of Arezzo. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 29, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, S. Italian grain silos in the 1930s. Which reuse? In Proceedings of REUSO 2015. III Congreso Internacional sobre Documentación Conservación y Reutilización del Patrimonio Arquitectónico y Paisajístico, Valencia, Spain, 22-24 October 2015; Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Eds. 1057-1064. Available online: http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1296-2074(16)30232-1/sbref0610 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Landi, S. The Italian Grain Silos in the 1930S. Analysis, Conservation and Adaptive Reuse. UNISCAPE En-Route 2016, a.I-4. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, S. Rural landscapes of the 20th century: from knowledge to preservation. Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment 2019, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, P. 2010. Representaçao tipológica através da fotografía silos no Alentejo, partindo da obra de Bernd e Hila Becher. Degree in architecture, University Évora, Portugal. 2010. Available online: https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/handle/10174/12180 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Ribeiro, I. , Diniz, A. Celeiro Epac. A Paisagem Industrial de Évora. Sciencia Antiquitatis 2019, 2, 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Maurílio, F. As arquiteturas do cereal em Évora. In Património industrial Ibero-americano: recentes abordagens; Palomares, S., Quintas, A., de Lima, F., Viscomi, P., Eds.; Biblioteca Estudos & Colóquios, Universidad de Evora: Evora, Portugal, 2020; Serie e-books nº 22; Available online: https://books.openedition.org/cidehus/13907.

- Benito, P. Patrimonio industrial y cultura del territorio. Boletín de la AGE 2002, 34, 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, C. Red Nacional de Silos y Graneros de España. In Proceedings of the 3rd Int Venue of the Agriculture and Food Productivion Section of TICCIH, Nogent-sur-Seine, France, 20-22 October 2011. Available online: http://www.patrimoineindustriel-apic.com/silo/5reseau%20national.pdf. (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Palmeiro, A. Postais Ilustradros: UM Olhar sobre os silos do distrito de Portalegre. In Proceedings of the III Seminário de I&DT, Portoalegre, Portugal, 6-7 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.V.; Marcelo, V.; Valenciano, J.B.; López-Díez, F.J. History, construction characteristics and possible reuse of Spain’s network of silos and granaries. Land Use Policy 2017a, 63, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, Manuel V.; Marcelo, V.; Valenciano, J.B.; Boto, J. Catalogación de los silos pertenecientes a la red española de silos y graneros en Castilla y León. In Proceedings of the IX Congreso Ibérico de Agroengenharia, Braganza, Portugal, 4-6 september 2017b. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.V.; Marcelo, V.; Valenciano, J.B.; López, F.J.; Pastrana, P. Spain’s national network of silos and granaries: architectural and technological change over time. SJAR 2020, 18, e0205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International council on monuments and sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Han, S.; Zhang, H. Progress and Prospects in Industrial Heritage Reconstruction and Reuse Research during the Past Five Years: Review and Outlook. Land 2022, 11, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federconsorzi. 1953. Federazione italiana dei consorzi agrari 1892-1952, Centro Studi e Pubblicazioni: Roma, Italy, 1953. pp. 91–102.

- Vaquero, M. Wheat-Storage in Facist Italy: Evolution and policies. In Property rights and their violations. Expropriations and confiscations, 16th-20th century; Lorenzetti, L., Barbot, M., Mocarelli, L., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2012a; pp. 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero, M. Il “granario dell`Urbe” del Consorzio agrario cooperativo di Roma. Roma moderna e contemporánea 2012b, 1, Año XX, 127-136. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo, V.; Valenciano, J.B.; López, J.; Pastrana, P. The D5 Silo of Manganeses of the Lampreana (Zamora): History, construction characteristics and technology. AART 2021, 2, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapperon, R. Silos e magazzini per ammassi granari. Progettazione, costruzione, gestione; Istituto delle Edizioni Accademiche: Udine, Italy, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Barciela, C.F. 1997. La modernización de la agricultura y la política agraria. Papeles de Economía Española 1997, 73, 112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A. Un análisis tecnológico sobre la red nacional de silos y graneros desde la ingeniería industrial en el ámbito agrario: ¿con qué maquinaria y cómo funcionaban? In Proceedings of the I Jornadas de patrimonio industrial agrario: silos a debate, Villanueva del Fresno (Badajoz), Spain, 26-28 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, C.J. El patrimonio industrial en España: Análisis turístico y significado territorial de algunos proyectos de recuperación. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2010, 53, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, J.M. , López-Sánchez, M., García, A.I.; Ayuga, F. 2015. Public abattoirs in Spain: History, construction characteristics and the possibility of their reuse. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAGI 900. 2024. Museo MAGI 900. Available online: https://www.magi900.com/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Habitat granario. 2024. Available online: https://habitatgranario.it/ 2023 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Mazzocchi, G.; Spadazzi, D. Parametric tools for BIM design: case study of "ex-Granaio dell'Urbe" of Rome. Level of Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Italy, 2022. Available online: http://webthesis.biblio.polito.it/id/eprint/23248 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Bertocchini, F. La valorizzazione del territorio attraverso il recupero del patrimonio storico architettonico. Il caso del silo agrario di Albinia (GR). Level of Thesis, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy, 11/05/2016. Available online: https://etd.adm.unipi.it/t/etd-04192016-112026/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Comune di Genova. Bando pubblico per la ristrutturazione e la gestione del silos Hennebique. Available online: https://www.portsofgenoa.com/it/archivio-notizie/item/1357-hennebique.html (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- JA. Informe final del expediente POZ/2004/SIL sobre la actuación en el silo de Pozoblanco iniciado en 2004; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Desarrollo Rural, Sevilla, Spain, 2006.

- MIRIB. Museo Internacional de Radiotransmisión Inocencio Bocanegra. Available online: http://www.belorado.es/node/329 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- MZ. Museo Zer0. Available online: https://www.museu0.pt/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Salazar, A. Del trigo al hombre. Rehabilitar el silo. Level of Thesis, Universidad politécnica de Cataluña, Barcelona, Spain, 15/09/2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2117/84444 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Río, A.S.; Blanco, S. La tempestad en el silo: reutilización de un almacén de grano para representaciones teatrales. In Espacios industriales abandonados. Gestión del patrimonio y medio ambiente, 15th ed.; Colección: Los ojos de la memoria; INCUNA; CICEES, Miguel A. Álvarez Areces: Gijón, Spain, 2015; pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.I.; Ayuga, F. Reuse of abandoned buildings and the rural landscape: The situation in Spain. ASABE 2007, 50, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.M. Methodological bases for documenting and reusing vernacular farm architecture. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.M.; Gallego, E.; García, A.I.; Ayuga, F. New uses for old traditional farm buildings: The case of the underground wine cellars in Spain. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Garzón, E.; Sanchez-Soto, P.J. Historic preservation, GIS, & rural development: The case of Almería province, Spain. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 42, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumain, X.; López, A.; Moreno, J.; Sanchez, D. Turismo como desencadenante de la recuperación de patrimonio industrial. In Proceedings of the III Jornadas de Patrimonio Industrial Activo, Murcia, Spain, 15-16 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).