The morphological and behavioral complexity of animals is arguably unrivaled in the living world. While most eukaryotes exist as single cells or small, undifferentiated colonies [

1], the multicellular bodies and diverse cell types of animals allow them to fly, swim, camouflage, communicate, and perform tetrad dissections [

2]. Given the importance of transcriptional regulation in animal development and cellular differentiation, it has been hypothesized that the cellular diversity of animals and their unusual biology stemmed from the evolution of more complex transcriptional regulatory mechanisms [

3,

4,

5].

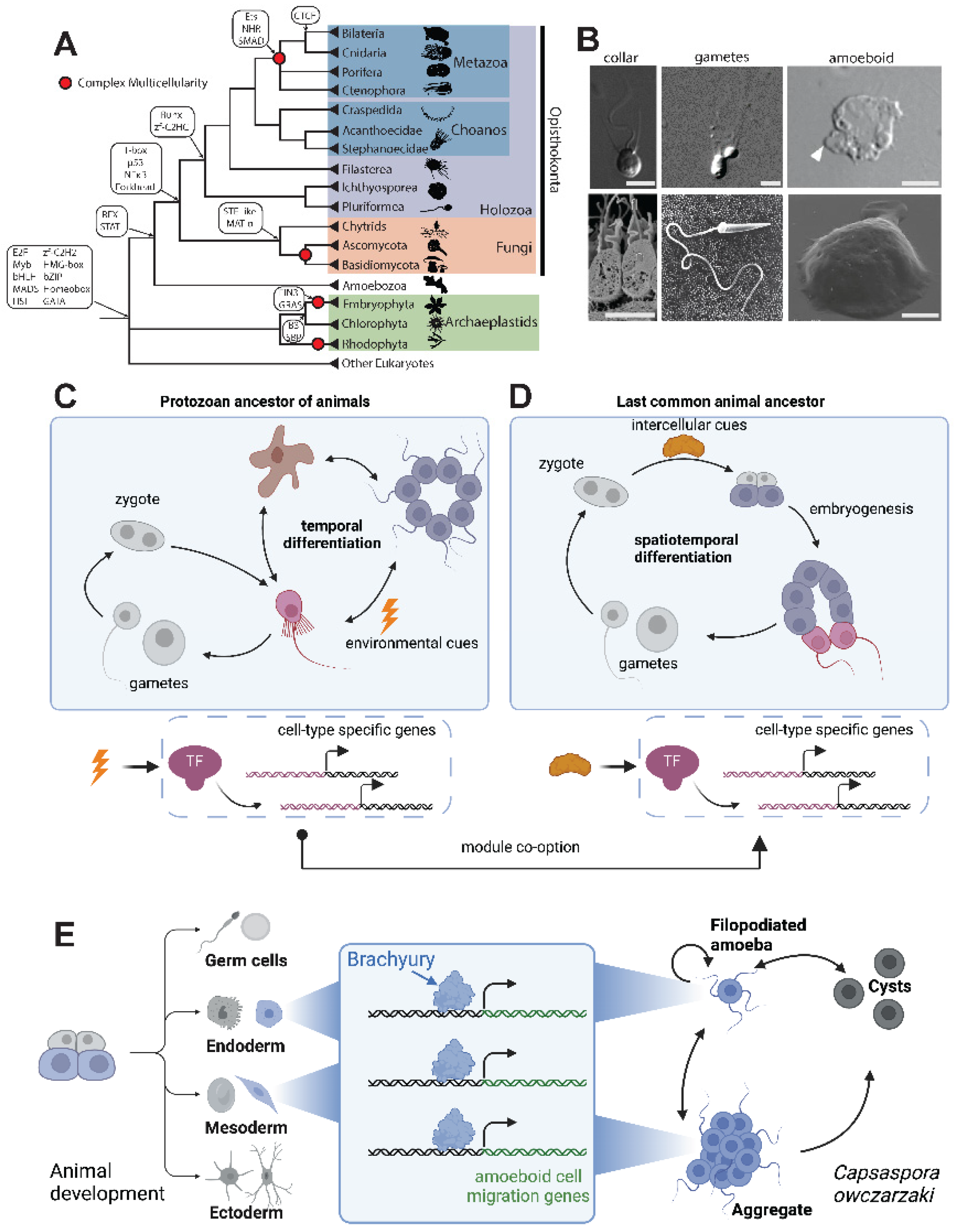

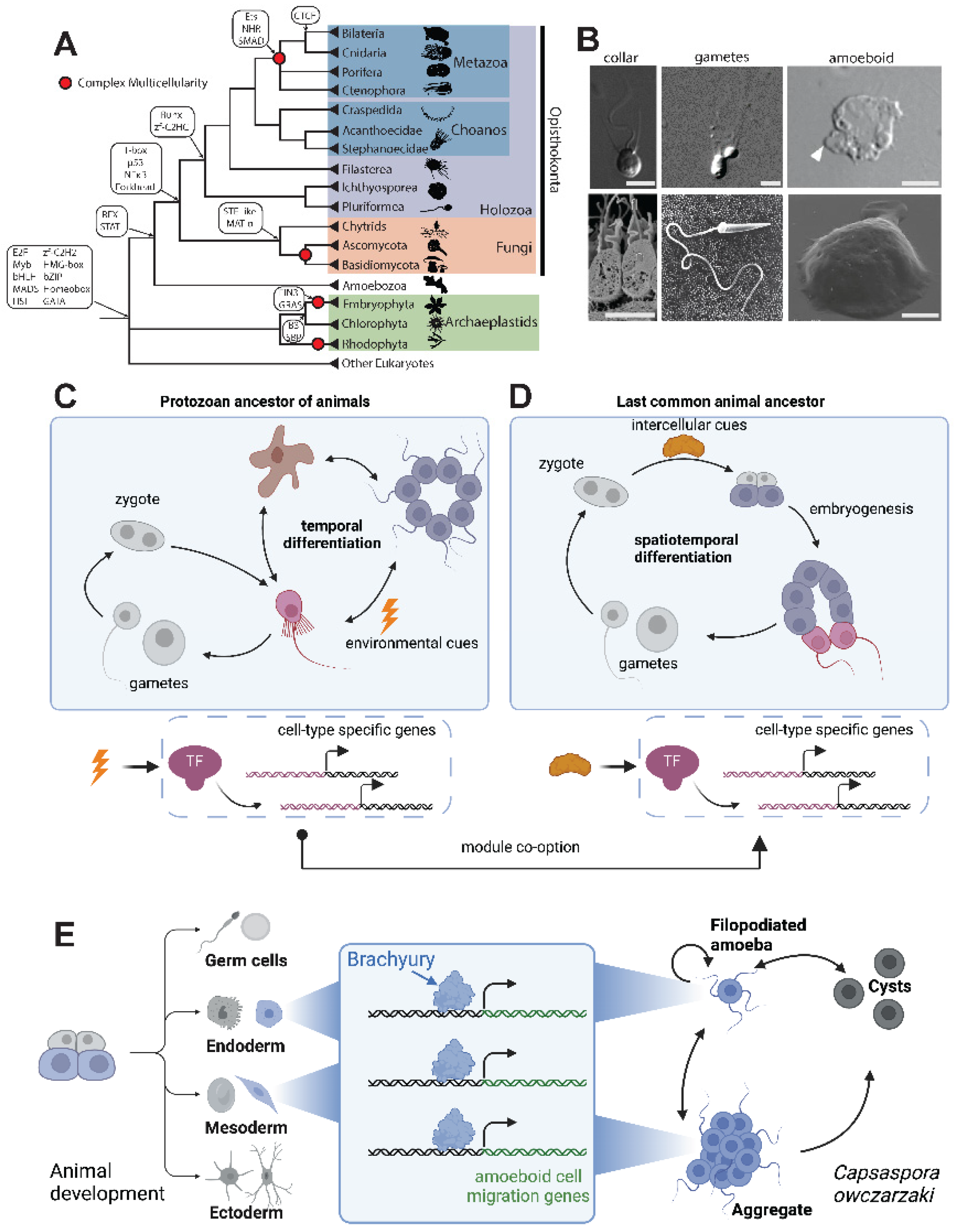

Although other multicellular lineages (e.g. plants and fungi) have independently evolved high degrees of developmental complexity, understanding animal origins can best be understood by comparing the transcriptional apparatuses of animals with those of their closest relatives: choanoflagellates, filastereans, and ichthyosporeans [

6,

7,

8] (

Figure 1A). Choanoflagellates are free-living aquatic microbial eukaryotes that eat bacteria, form small colonies [

9], and transition between a diversity of cell types in response to environmental factors [

10,

11,

12,

13] (

Figure 1B). Filastereans also transition between different cell types – amoebae, cysts, and flagellated cells – and have the capacity for aggregative multicellularity [

14,

15], while ichthyosporeans develop their multicellular forms through multi-nucleated coenocytes that later cellularize and disperse [

16,

17]. The function and morphology of these cell types, including collar cells [

18,

19], anisogamous gametes [

10], and amoeboid cells [

11] (

Figure 1B) mirror some animal cell types, suggesting homology awaits more thorough investigation by genetic studies. The cell differentiation capabilities of all these groups may be underestimated given the impossibility of establishing the full diversity of ecological conditions in the lab.

The plasticity observed in modern-day choanoflagellates, filastereans, and ichthyosporeans, supports the hypothesis that the unicellular ancestor of animals was also capable of differentiating between at least a few cell types [

1,

4,

20,

21]. These cell type transitions are usually triggered by environmental conditions, including starvation and the presence of specific chemical cues [

12,

15,

22]. These data suggest that the unicellular ancestor of animals was capable of environmentally-regulated cellular differentiation potentiated by dynamic transcriptional regulation. The temporal-to-spatial transition (TST) hypothesis posits that regulatory modules controlling temporal differentiation in the protozoan progenitors of animals laid the foundations for the evolution of animal cell types and developmental programs [

1,

8,

20,

21]. This hypothesis predicts that cell differentiation programs in animals would show some conservation with environmentally-responsive cell differentiation mechanisms in close animal relatives, with homologous transcription factors regulating similar sets of target genes to implement similar cellular phenotypes (

Figure 1C,D). Some evidence for this hypothesis has emerged. For example, the transcription factor Brachyury regulates genes for amoeboid cell migration (myosin complex, actin regulation) in the filasterean

Capsaspora owczarzaki in a cell-type specific manner [

23], while animal Brachyury often regulates similar genes in the mesodermal and endodermal lineages [

24,

25] (

Figure 1E). Other evidence for conservation of gene regulatory programs between animals and choanoflagellates, specifically those governed by RFX and Myc:Max, will be discussed later.

It is still unclear whether the evolution of transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in animal origins was also accompanied by large shifts in complexity. Comparisons between bilaterians and non-animals have generally been interpreted as evidence that the answer to this question is an obvious “yes.” However, it is important to make a distinction between evolutionary events that precipitated animal origins vs. those that subsequently accompanied the diversification of extant animal groups. To evaluate whether animal transcriptional regulation differs from that of pre-animal life, we here consider various metrics of transcriptional complexity, comparing what is known in animals, particularly early branching lineages, and close animal relatives. We find little support for many commonly invoked explanations for the uniqueness of animal transcriptional complexity, including large increases in transcription factor (TF) numbers, novel TF families, and the use of distal enhancers. Instead, we find more support for the co-option and elaboration of ancestral transcriptional regulatory modules and the evolution of novel protein-protein interactions, likely both facilitated by gene duplication events.

Transcription Factor Abundance Did Not Increase Substantially during Animal Origins

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that regulate transcription by binding to DNA in a sequence-specific manner [

26], thereby influencing (positively or negatively) the recruitment or activity of RNA polymerase II. Although the founding members of most TF families were originally detected through a combination of genetics and biochemistry, many TFs can now be identified in genome assemblies by sequence similarity to a DNA-binding domain (DBD) from a previously-characterized TF family [

26,

27].

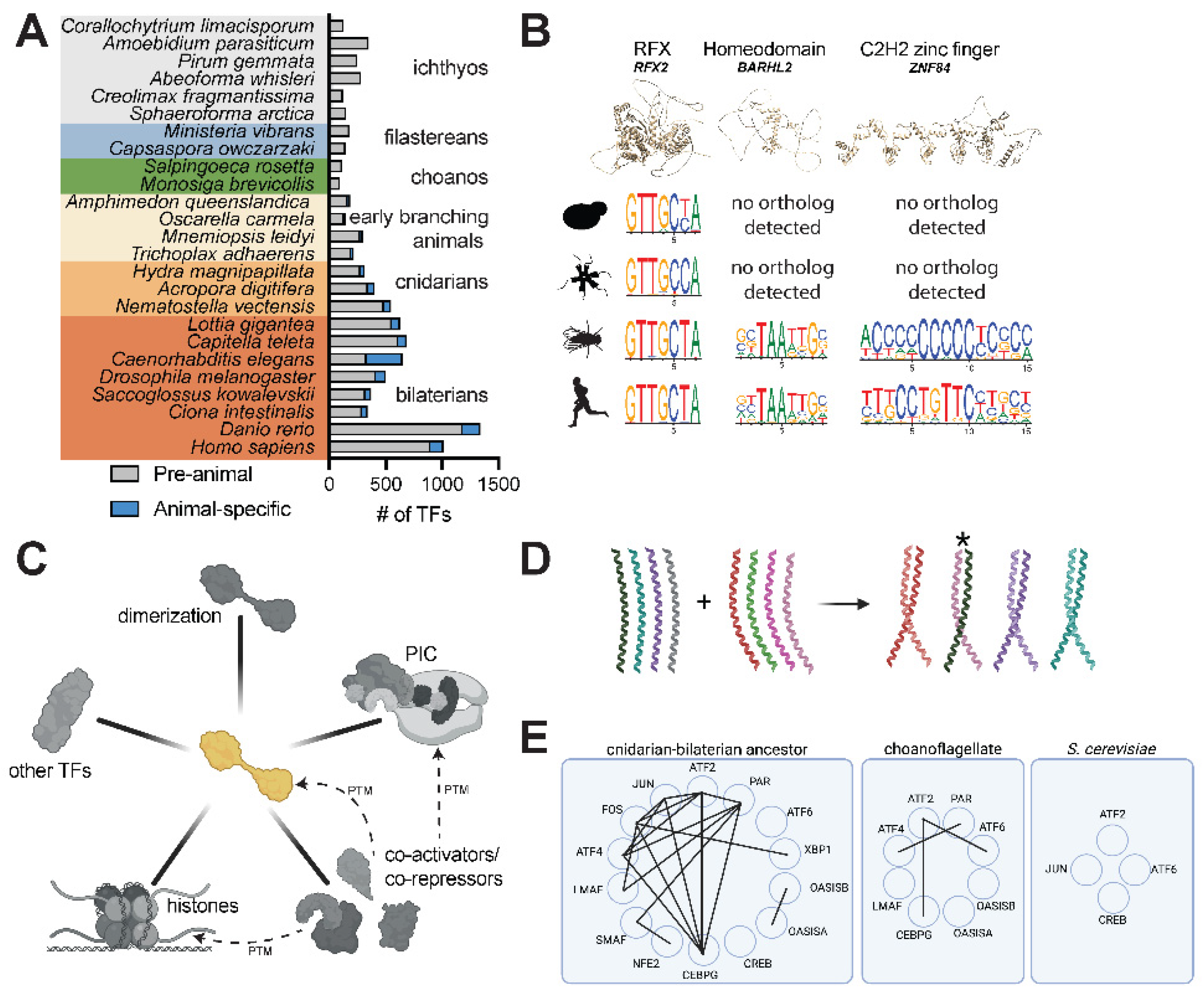

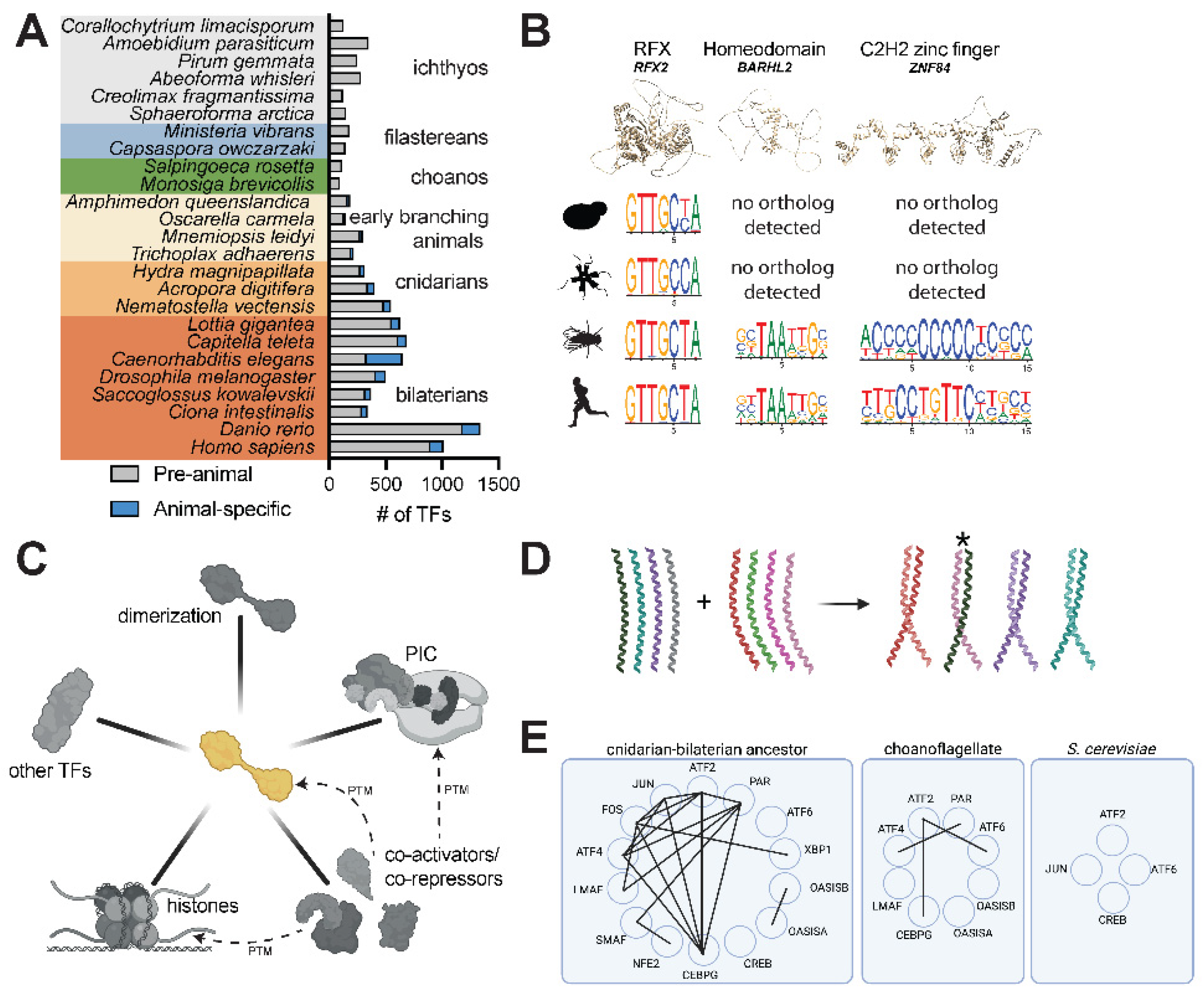

While many vertebrates encode >1000 TFs, animals in most other phyla encode 100-700 predicted TFs. Early branching animals like placozoans, ctenophores and sponges typically encode fewer than 300 TFs (

Figure 2A) [

27,

28]. Similarly, the closest living relatives of animals (choanoflagellates, ichythosporeans, and filastereans) generally encode 100-300 TFs, with the current high water mark being the 345 TFs identified in the ichthyosporean

Amoebidium parasiticum (

Figure 2A) [

27]. It is difficult to reconstruct the exact TF content of the last common ancestor of animals, largely due to the difficulty of confidently detecting gene orthologs across such large evolutionary distances. Despite this limitation, the comparable number of TFs observed in sponges (143-180), ctenophores (295), and unicellular relatives of animals (91-345) imply that a large increase in TF numbers was likely not a component of animal origins.

However, there is some evidence for TF expansion within individual gene families during animal origins. For instance, analysis of Forkhead sub-families has indicated that there were three Forkhead genes in the last common ancestor of animals and choanoflagellates, which expanded to at least 11 genes in the last common ancestor of animals [

29]. A proper evaluation of TF number changes at different ancestral nodes will require not just counting TFs in extant lineages but ascertaining their evolutionary relationships to distinguish between ancestral changes vs. multiple lineage-specific changes.

Identifying transcription factors by DBD similarity can produce false positives when proteins encode a DBD but do not function as transcription factors, e.g. C2H2 zinc fingers involved exclusively in RNA binding [

30] or homeodomains co-opted for ceramide synthase regulation [

31]. Also problematic are false negatives: transcription factors that are not identified because the relevant DBD has not yet been identified. To this point, 69 genes without a canonical DBD have been identified as human TFs by the criterion of sequence-specific DNA binding [

26]. It is difficult to know

a priori how many TFs and DBD families have yet to be discovered in less well-studied organisms. Choanoflagellates, filastereans, and ichthyosporeans may all sport lineage-specific TFs that remain to be identified.

Animals, Like Most Major Classes of Eukaryotes, Evolved Lineage-Specific TF Families

At present, between 70 and 100 families of TFs have been identified in eukaryotes [

26,

32,

33]. Many of these TF families date to the last common ancestor of eukaryotes, but there also are TF families that appear to have originated in particular lineages during the eukaryotic radiation [

32]. Two sources of lineage-specific TF families are gene innovation from non-coding sequence and rapid evolution from a pre-existing gene, in which the pace of evolutionary change makes their shared ancestry difficult to detect.

Lineage-specific TFs in animals include nuclear hormone receptors, Ets, and MADF TFs (

Figure 1A) [

32]. These all appear in the genomes of early branching animals and have not been detected in non-animals, indicating that they first evolved along the animal stem lineage [

34,

35,

36]. However, animals are not the only group of eukaryotes to have evolved lineage-specific TF families, which are also seen in fungi (e.g. STE) and land plants (e.g. GRAS) (

Figure 1A) [

27]. Among protists, the IBD TF in

Trichomonas vaginalis appears to be lineage-specific [

37], while apicomplexans encode a lineage-specific family of TFs related to but highly divergent from AP2 TFs [

38]. These ApiAP2 TFs make up the majority of identifiable TFs in apicomplexans [

27]. The existence of uncharacterized, lineage-specific TF families may present a major challenge when it comes to assessing full TF repertoires across large evolutionary distances, such as those that separate animals and their closest living relatives. Given that early branching animals and close relatives of animals remain poorly studied, it is not clear how confident we can be of the differences between both the number of TFs as well as the number of TF families in animals versus non-animals.

Finally, it is not obvious why a wider diversity of TF families would drive increased transcriptional complexity. The TF families novel to animals do not display features of particular salience with regards to integrating or effecting combinatorial information. One argument may be that new TF families diversify the lexicon of DNA binding sites that can be used as regulatory information, but as will be discussed next, novel DNA binding preferences can arise just as easily from the diversification of existing TFs.

Animals Origins Likely Did Not See a Diversification of TF Binding Specificities

Another metric by which a TF repertoire can expand its regulatory capacity is in its ability to recognize a wider range of DNA motifs. Mutations affecting DNA binding can change the sequence specificity of a TF, so that homologous TFs in the same species or different species can recognize different DNA motifs [

39].

Different TF families display very different rates of evolution in DNA binding specificity (

Figure 2B). The C2H2 zinc finger and Myb TFs display fast evolution of DNA binding specificity. However, many families – including Homeodomain, nuclear receptor, Ets, Sox/HMG, and Forkhead – show highly similar binding specificities across Bilateria (

Figure 2B) and likely even in cnidarians [

40]. Systematic surveys comparing TF specificities between animals and their closest relatives have not been published. Thus far, the binding specificities of only a few TFs have been compared between animals and their close relatives: Myc:Max [

41], RFX [

42] and T-box [

43]. In all cases, the DNA-binding specificities were almost identical in animal and non-animal orthologs (

Figure 2B). Systematic surveys comparing TF binding specificities between animals and their close relatives will be needed to fully assess the relative stability of binding specificities on the animal stem lineage.

Given that the evolution of new DNA binding specificities is particularly accelerated in just a few TF families, it is especially notable that one of these families, the C2H2 zinc fingers, have undergone large expansions multiple times in animals, including in mammals and cephalopods [

28,

44]. However, there is no clear evidence that expanding and diversifying C2H2 zinc finger repertoires played a role in animal origins, as the number of C2H2 TFs in sponges and placozoans is similar to the numbers found in choanoflagellates and filastereans, while ctenophores and ichthyosporeans show higher numbers, likely due to independent expansion events, which appear particularly common for this TF family, even in closely related species [

28]. Therefore, there is little evidence that the TFs of the first animals had a wider range of DNA binding specificities than those of their unicellular ancestors.

Animals Exploited the Possibilities of Heterodimerizing TF Networks

Transcription factors participate in a variety of protein-protein interactions (PPIs): with co-activators and co-repressors, the pre-initiation complex machinery, other TFs, histones, and chromatin readers and writers (

Figure 2C). These interactions provide a rich substrate for the evolution of transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. While some protein-protein interactions can be traced to well-conserved and identifiable interfaces, others require regions that may be short, unstructured, and highly divergent in sequence space [

45]. The presence of these small and labile interaction interfaces, as well as the complex and non-linear interaction networks among PPIs, makes it difficult to accurately predict protein-protein interactions of TFs solely from genomic sequence. This practically limits the number of taxa for which we have data on the PPIs for a given TF, with most data coming from a few model organisms.

Among the limited data we do have, there is some suggestion that animal TFs may exhibit a wider diversity of PPIs than the same TFs in non-animals. One example comes from the bZIP family, which can bind DNA as homodimers or heterodimers [

46]. By testing the

in vitro binding affinities of hundreds of potential bZIP heterodimers across a range of taxa, it was shown that bilaterian and cnidarian bZIPs former denser interaction networks than do those from yeast or choanoflagellates [

47] (

Figure 2D). For some bZIP heterodimers, the DNA binding preference of the heterodimer is a concatenation of the preferences of each binding partner, while in other cases emergent DNA binding specificities result [

46]. Beyond the impact on DNA binding specificity, different bZIP heterodimers may also have different effects on recruiting transcriptional co-factors and other downstream processes. Therefore, increased capacities for heterodimerization allowed the animal bZIP network to become more complex, even in the absence of large changes in TF family size or the DNA binding specificity of individual TFs. One caveat to this published work is the lack of functional data from early branching animals, limiting the relevance of this data for re-constructing animal origins in particular, since bZIP heterodimerization may represent a feature that evolved in the cnidarian-bilaterian common ancestor, after the divergence of earlier branching groups.

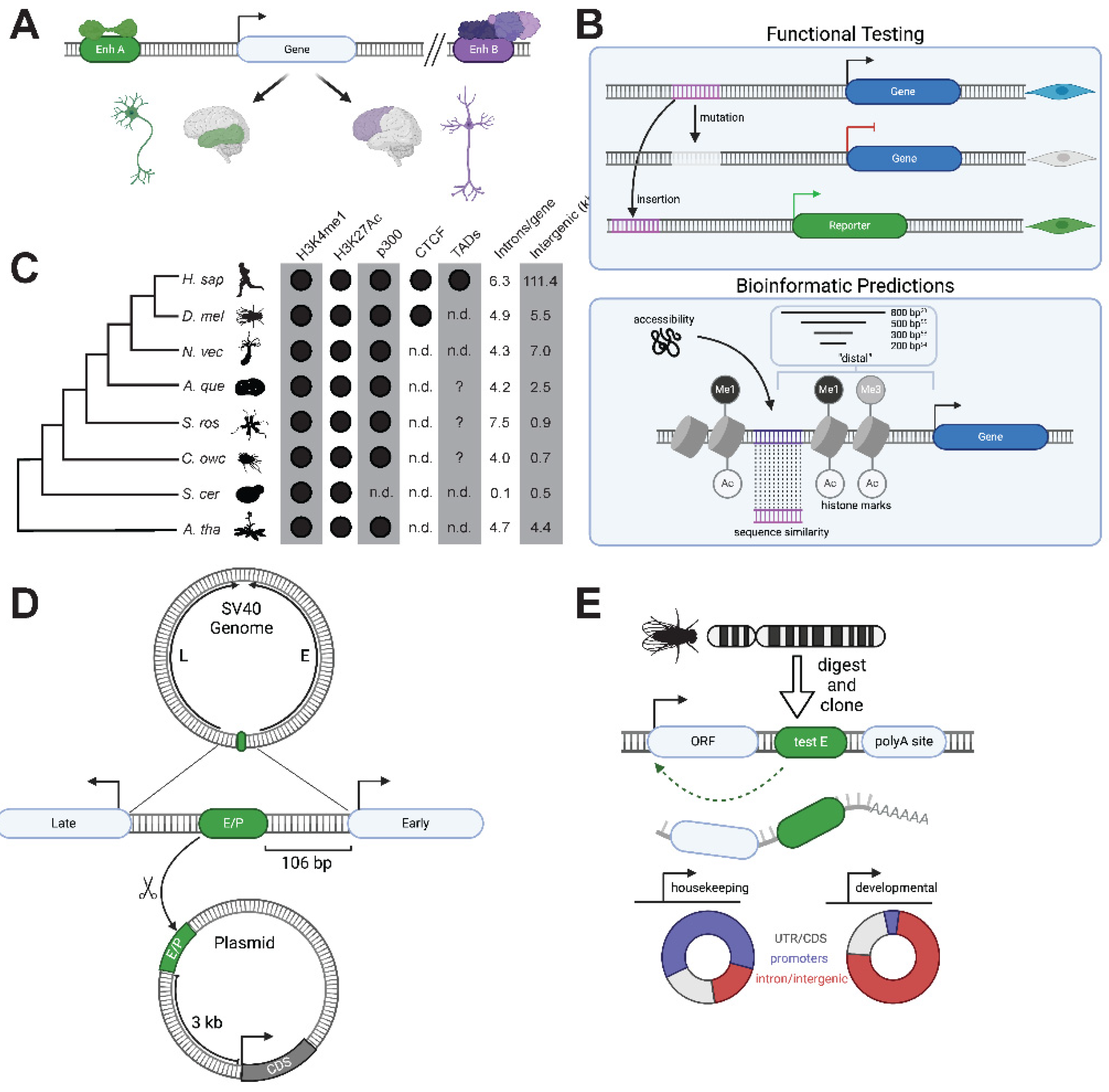

Did the First Animals Expand or Invent the Use of Distal Enhancers?

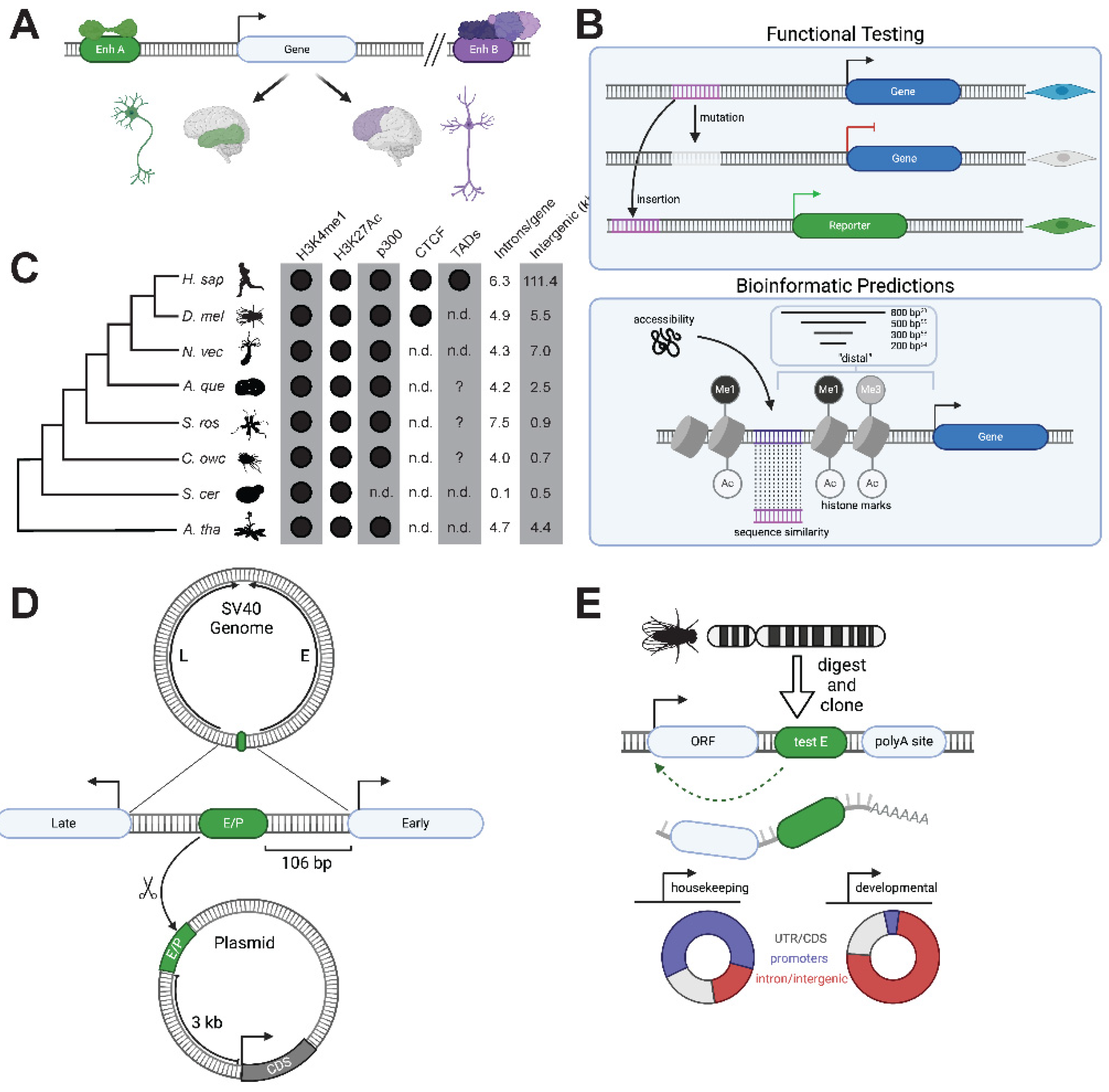

In animals, the transcription level of a gene can be affected by regulatory sequences called enhancers, which can be separated from their target core promoters by dozens to millions of bases [

48,

49]. Particular attention has been paid to “distal” enhancers, which are located in regions far from the core promoter, although no consistent threshold has been used for “far”. Many animal developmental genes are controlled by multiple enhancers, the modularity of which allows the gene to be activated in different developmental contexts [

50,

51] (

Figure 3A). This has led to the hypothesis that the evolution of distal enhancers was essential for the evolution of animal developmental complexity [

5,

48]. Supporting this, transcriptional regulation driven by distal enhancers has been well-characterized in several bilaterian model systems – human cells, mice, zebrafish, and

Drosophila.

Analysis of chromatin features has suggested that basally branching animals might also utilize distal enhancers (

Figure 3B). In bilaterians, enhancers are associated with chromatin marks such as H3K27Ac and H3K4me1, or depositors of these marks such as the acetyltransferase p300 [

52]. In the cnidarian

Nematostella vectensis, many p300 peaks can be identified more than 300 bases from transcription start sites and these peaks show both H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac enrichment [

53]. About 75% of these tested enhancers were validated in reporter assays, in which the expression pattern of a heterologous construct for a putative enhancer was similar to the

in situ staining pattern for the mRNA of the nearest gene. In the sponge

Amphimedon queenslandica, patches of H3K4me1 enrichment more than 200 bases from transcription start sites identified several putative regulatory sites [

54], while ATAC-seq profiling of

A. queenslandica development showed that ~60% of dynamically regulated ATAC-seq peaks are >500 bp from transcription start sites [

55].

Another approach for identifying enhancers in basally branching animals is to take advantage of microsynteny conservation, in which the adjacent chromosomal locations of two genes is maintained due to one gene harboring a regulatory element of its neighbor. Indeed, this approach has identified a putative sponge enhancer that can drive cell-type specific expression in zebrafish [

56], although its function, or that of any sponge enhancer, has yet to be ascertained in its native context due to technical limitations in this phylum.

Despite this pioneering work, the scope of distal regulation implicated by this data remains murky. The distance thresholds often used to identify regulatory elements (200 bp-500 bp) are within the functional range of cis-regulatory elements in

S. cerevisiae, which is not typically understood to have distal regulation [

57]. Second, the functional relevance of all sites marked by certain chromatin marks and/or genome accessibility are uncertain. For instance, in both flies and mouse embryonic stem cells, genome-wide loss of H3K4me1 methylation has only minor phenotypic and gene-regulatory consequences [

58,

59]. It is likely that basally branching animals still use a regulatory logic dominated by proximal cis-regulatory sites. In fact, by building a machine learning model from an scRNAseq dataset of

Amphimedon queenslandica, patterns of gene expression can be well-predicted by promoter proximal elements alone [

60]. Enhancers derived from microsyntenic pairs may present an exception, albeit perhaps a rare one, as very little microsynteny is conserved between bilaterians and basally branching animals [

61], despite the high conservation of microsynteny within bilateria [

62].

The best approach for ascertaining the extent of distal regulation in basal animal phyla will be to functionally test putative enhancers and to clarify the mechanisms which make distal regulation possible, a pre-requisite for describing the phylogenetic distribution of such mechanisms. Among these, the role of 3D chromosome organization has been shown to be essential for potentiating longer-range enhancer-promoter reactions [

63,

64]. The longest-range interactions (up to 2 Mb) are seen in vertebrates and are generated by chromosome looping through a cohesin/CTCF mechanism [

65,

66]. Yet growing evidence suggests that this mechanism may not operate outside of deuterostomes (despite CTCF evolving in the bilaterian stem lineage) and that 3D chromosome contacts in

Drosophila, other invertebrates, and non-animal eukaryotes are created through distinct mechanisms, including self-organization mediated by histone modifications and transcriptional activity itself [

64,

67,

68,

69]. The relative contributions of these other mechanisms, and their phylogenetic distribution in basally branching animals and close animal relatives remains to be deciphered. All in all, the extensive use of distal regulation may be more central to the origins of bilaterians (and possibly the origin of the bilaterian-cnidarian common ancestor) than to the origins of the first animals.

In parallel, further work is needed to ascertain whether the closest animal relatives use distal enhancers. In

Capsaspora owczarzaki, chromatin accessible sites distal to transcription start sites (defined as 800 bp) did not show enrichment of H3K4me1 over H3K4me3 and were smaller than intergenic chromatin-accessible sites found in animals [

23]. However, no

Capsaspora sites could be functionally tested at the time and the limitations of using H3K4me1 as an enhancer proxy have been discussed. H3K4me1, H3K27Ac, and many other “regulatory” chromatin marks, are widespread in eukaryotes [

70] (

Figure 3C). Finally,

Capsaspora, like choanoflagellates and other close animal relatives, has a compact genome with small intergenic regions, meaning that there are very few intergenic regions >800 bp from transcription start sites (

Figure 3C). This criterion rules out a whole class of putative enhancers, which are the promoters of adjacent or nearby genes. Indeed, the literature on distal enhancers supports the prevalence of promoter proximal sequences acting as distal enhancers at other promoter regions.

In fact, the prototypical SV40 enhancer acts in its endogenous context as a promoter proximal element for regulating viral genes [

49,

71] (

Figure 3D). Some attempts have been made to systematically characterize all the possible distal regulatory information in a given genome. An example of this is the STARR-seq assay, which inserts a library of genomic DNA in the 3’ UTR of a gene driven by a minimal promoter, so that effective enhancers transcribe themselves and can be identified in high throughput by next-generation sequencing. STARR-seq assays in

Drosophila S2 cells have demonstrated thousands of promoter-proximal elements with distal regulatory capacity [

72] (

Figure 3E). Therefore, if distal enhancers do exist in unicellular relatives of animals, we have not yet applied the appropriate techniques to identify them. Intriguingly, evolutionary analysis of intron gains and losses point to an increase in intron numbers in the last common ancestor of animals and choanoflagellates [

73], which may also provide substrates for distal regulatory sequences.

In summary, current data does not clearly demonstrate the widespread use of distal enhancers in basally branching animals, nor does it convincingly show the lack of distal enhancer usage in close animal relatives. While the temptation to invoke distal enhancers as the bridge between pre-animal and animal transcriptional regulation is understandable given the use of enhancers in bilaterian development, we argue against the necessity of distal enhancers for animal origins.

Co-Option and Elaboration of Transcriptional Regulatory Modules in Animal Origins: Two Case Studies

Genome sequencing of choanoflagellates and other animal relatives revealed that many TFs essential for animal development and cell type differentiation are also present in protistan relatives of animals, including p53, Runx, Myc:Max, T-box, RFX, and NF-κB TFs [

27,

74]. The presence of animal developmental TFs in non-animals revealed that the origin of animal developmental gene regulation was not simply due to the evolution of novel “developmental” genes. Rather, many animal developmental genes were likely co-opted from functions they previously served in a unicellular, non-animal context. In recent years, some examples have begun to accumulate for the role of these TFs in close animal relatives. This functional data allows often shows a core function conserved between animals and their unicellular relatives, and thus likely conserved from their common ancestor. Beyond exhibiting the conservation of core transcriptional modules from pre-animal to animal life, these examples also highlight how animals have elaborated on these ancestral mechanisms, through a combination of cis-regulatory DNA changes, gene duplication and sub-functionalization, and novel protein-protein interactions domains. We propose that these types of evolutionary changes, rather than wholesale increases in TF numbers of the advent of distal enhancers, explains the transcriptional regulatory changes driving animal origins.

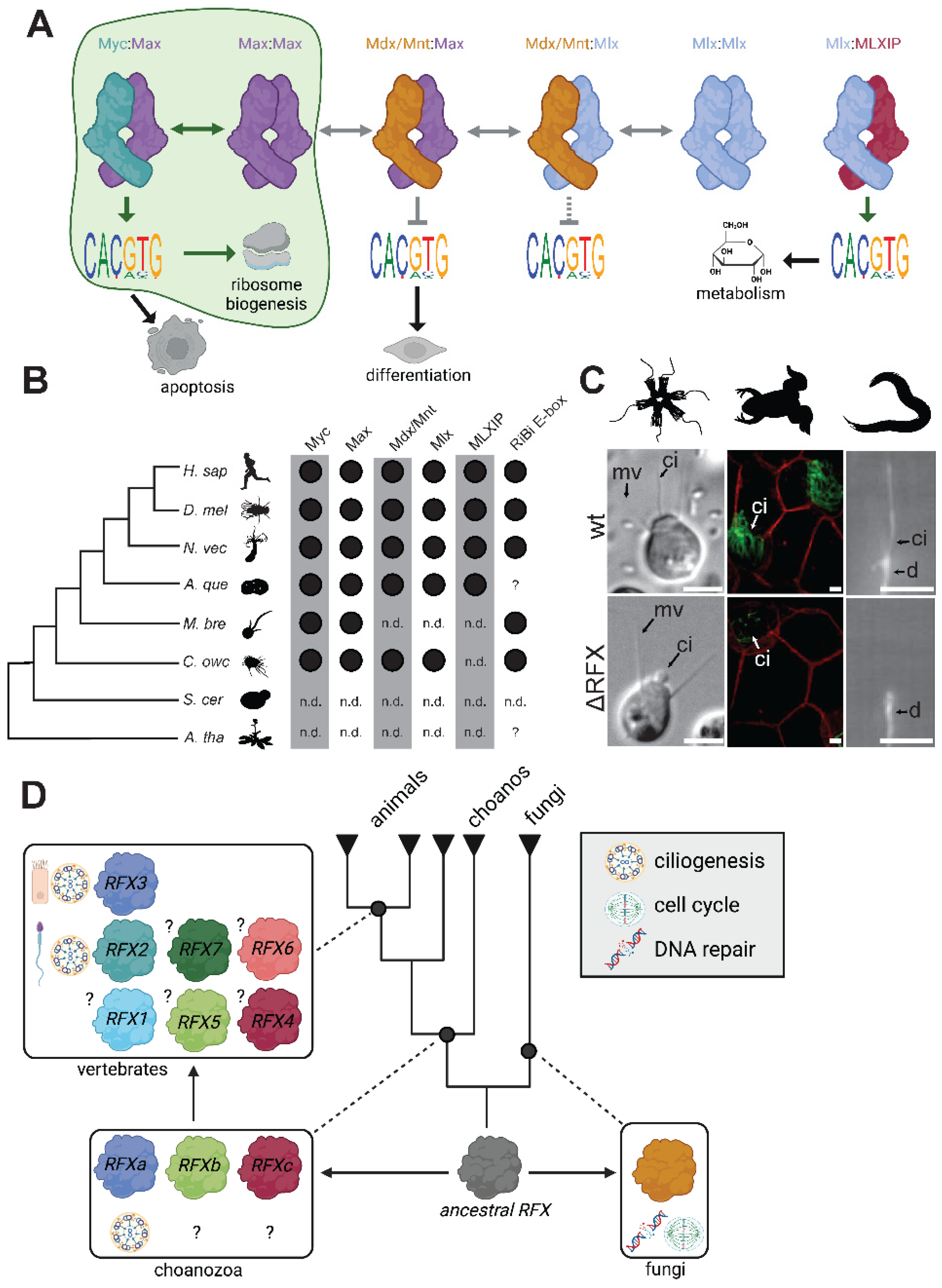

Myc:Max

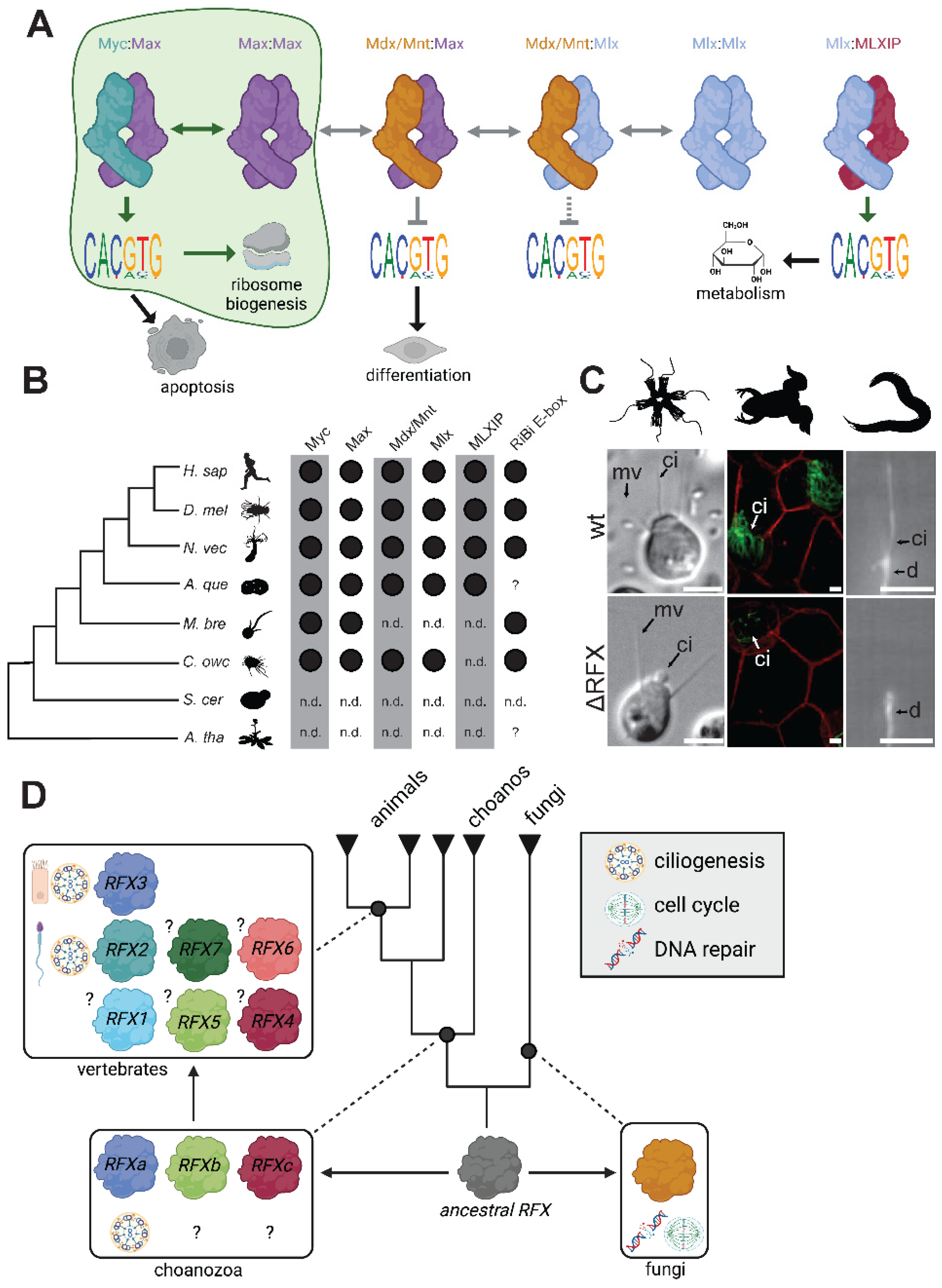

Together, the bHLH-family Myc and Max transcription factors regulate a broad diversity of cell fates in animals, including division, differentiation, and apoptosis [

75,

76]. Myc:Max heterodimers promote cell division by activating large suites of genes, including those for ribosomal proteins and RNAs required for ribosome biogenesis [

75,

77,

78,

79,

80]. Myc:Max bind a palindromic DNA motif called the E-box (CACGTG) (

Figure 4A). The ubiquity of Myc:Max binding sites [

81] and the large number of genes reported to be activated by Myc have led to the proposal that Myc:Max may act as a universal amplifier of transcription, although this model has been debated, including whether such a phenomenon is due to direct or indirect effects of Myc:Max activation [

82,

83,

84,

85]. Because Myc requires Max for heterodimerization and binding, Myc activity can be indirectly inhibited by the sequestration of Max, either when Max forms homodimers or heterodimerizes with Mdx or Mnt [

86]. The extended Myc network includes the Max paralog Mlx, which can also homodimerize or heterodimerize, including with MLXIP, through which it regulates metabolic genes [

76] (

Figure 4A).

Myc and Max are encoded by close animal relatives, including choanoflagellates and

Capsaspora owczarzaki.

Capsaspora additionally encodes an Mdx and an Mlx protein (

Figure 4B). In both organisms, the role of Myc:Max in regulating ribosome biogenesis is likely conserved (

Figure 4A). E-boxes can be found in the promoter regions of conserved ribosome biogenesis genes in animals, the choanoflagellate

Monosiga brevicollis, and the filasterean

Capsaspora owczarzaki, but not in

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

80] (

Figure 4B). Moreover,

M. brevicollis Myc and Max can heterodimerize and bind to E-boxes

in vitro [

41].

The apparent conservation of Myc:Max regulation of ribosome biogenesis in choanozoans and

Capsaspora suggests that the Myc:Max network regulated ribosome biogenesis in the unicellular progenitors of animals. This in itself represents an evolutionary change, as this sub-family of TFs is not found in the vast majority of eukaryotic diversity [

41]. It is possible that the consolidation of ribosome biogenesis control under Myc:Max regulation opened new possibilities for increasingly complex regulation, as the network of homodimers and heterodimers within this sub-family allows for many possible inputs to influence the essential decision of whether to undergo cell division. This is analogous to the example of bZIPs presented earlier, in which animals appear to have utilized an increased toolkit of heterodimers to expand their regulatory capacity.

However, Myc functionality in animals goes beyond regulating ribosome biogenesis. Myc binds to and regulates large numbers of genes, with only partially overlapping targets in different cell types [

81]. The control of this elaborate network requires combinatorial action with other genes beyond Max and may involve novel types of protein-protein interactions. For instance, the Myc homology box IV domain is only found in vertebrates and regulates apoptosis [

87]. The Myc example shows how a core TF regulatory mechanism evolved in the unicellular ancestors of animals and was later expanded to play diverse roles in animal development. This expansion of possible functions derives from the combinatorial power of distinct heterodimers to regulate Myc:Max activity as well as the evolution of other types of protein-protein interactions [

88]. Future work, including elucidating the mechanism behind the transcriptional amplification capacities of Myc and whether these mechanisms are phylogenetically conserved across animals and close relatives of animals, will provide important insight into the evolution of this important regulator of cell proliferation.

RFX

RFX (regulatory factor X) TFs regulate ciliogenesis in a wide diversity of animals, from vertebrates to

Drosophila to

C. elegan [

89,

90,

91] (

Figure 4C). Cilia are produced by many animal cell types, including sperm, most epithelial cells, and numerous cells of sensory function (photoreceptors, olfactory neurons) [

92]. Ciliogenesis requires the complex orchestration of hundreds of genes, and the coordinated transcription of this set must occur in the proper cell types at the right developmental time points [

93]. Animal RFX TFs regulate ciliogenesis target genes by binding to the recognition site GTTRCY (

Figure 2B) [

94]. Notably, RFX TFs are not found in most eukaryotes (many of which bear cilia), being restricted to opisthokonts and amoebozoans [

42,

91,

95]. Ascomycete fungi, which lack cilia, use RFX TFs to regulate DNA damage repair and the cell cycle [

96,

97,

98] (

Figure 4D)

Recent work explored the function of RFX TFs in the choanoflagellate

Salpingoeca rosetta, revealing a conserved (and therefore pre-animal) regulatory link between RFX and ciliogenesis genes [

42]. This study also showed that the RFX TF family expanded from one to three members on the choanozoan stem lineage, which may have coincided with its acquisition of a role in regulating ciliogenesis [

42]. Interestingly, one specific sub-family that resulted from this duplication is responsible for almost all published reports of RFX regulating ciliogenesis, in both animals and now choanoflagellates [

42,

91,

99].

The three ancient choanozoan RFX sub-families underwent additional expansions in vertebrates, further partitioning functions. For instance, RFX2 in mammals specifically controls ciliary gene expression in spermatogenesis [

100], while RFX3 controls ciliary gene expression in other tissues [

101]. RFX1, on the other hand, is embryonic lethal in mice [

102], and may have retained a cell cycle function that may be as ancient as opisthokonts, given the role of RFX in cell cycle regulation in fungi [

103] and the growth defect observed in an RFX knockout in choanoflagellates [

42]. Functional specificity may be driven by differences among family members in protein-protein interactions. In support of this, vertebrate RFX2 (which is the predominant vertebrate RFX implicated in ciliogenesis) and FoxJ1 have been shown to physically associate [

89].

Overall, the evolution of RFX function shows how TF families can both acquire new functions as well as partition pleiotropic functions through duplication and divergence, even while all family members retain the ancestral DNA-binding specificity. The RFX-ciliogenesis module, while active at almost all times in choanoflagellates, is active only in specific animal cell types through the selective transcription of RFX itself, a change that would have required the acquisition of specific cis-regulatory sites near the RFX gene.

Conclusion

The studies of Myc and RFX show how TFs coordinate gene expression to enable cellular functions in close animal relatives. Notably, these relatives all exhibit complex life histories with several functionally distinct cell types [

12,

15,

16,

22]. RNA sequencing experiments have shown these cell types to be transcriptionally distinct, with numerous TFs differentially expressed [

23,

104]. Some of these cell types are part of the sexual cycle (gametes, spores), while others form in response to environmental cues or stressors (colonies, aggregates, cysts, dispersal forms). Overall, we are assembling a picture of a unicellular ancestor of animals that could regulate its gene expression and cellular phenotype to perform multiple functions: amoeboid and/or flagellar-driven motility, digestion, secretion, sex, and cell division. Some regulatory modules (RFX and ciliogenesis, Myc:Max and ribosome biogenesis) were likely already in place. It is likely that cell differentiation preceded animal origins as part of temporally defined and environmentally-responsive programs [

20,

21]. How did this transcriptional regulatory apparatus evolve to facilitate the emergence of multicellularity and spatiotemporal cell differentiation in the first animals? Some explanations that have been provided for this transition, such as a large increase in the number of transcription factors or the evolution of a distal enhancer mechanism, are not strongly supported. What does seem clear is that animal origins required the spatially regulated control of at least some ancestral transcriptional modules, likely through the regulated transcription of those transcription factors by cis-regulatory DNA changes. This emerged alongside cell-cell signaling pathways like Wnt, Notch, and TGF-beta. Transcription factors were able to co-opt new functions or sub-functionalize an existing set of pleiotropic functions through gene duplication and divergence events. Finally, it is likely that novel protein-protein interactions created more combinatorial possibilities for gene regulation.

Figure 1.

The evolutionary foundations of animal transcription factors and cell differentiation. (A) Eukaryotic phylogeny with the origins of transcription factors (TF) and complex multicellularity (red circles) indicated. Rounded rectangles contain names of representative TF families that evolved during eukaryotic evolution and radiation. We define complex multicellularity as that of organisms exhibiting spatiotemporal patterns of cell differentiation [

1]. TF families are evolutionarily coherent groups of genes characterized by unique DNA binding domains shared by all members. Many TF families found in animals were likely already present in the last common eukaryotic ancestor, while other TF families evolved during eukaryotic radiation [

32,

105]. Some TFs evolved along the animal stem lineage (e.g. Ets, NHR, SMAD), while others evolved earlier and are shared by outgroups such as other holozoans, fungi, and amoebozoans (e.g. Runx, p53, and RFX). (B) Cell types of similar form and function can be found in their closest living relatives. Top left: choanoflagellate [

106]. Bottom left: sponge choanocyte (fl = flagellum, n = nucleus) [

107]. Top center: anisogamous gametes from choanoflagellates (photo credit: Alain Garcia de Las Bayonas). Bottom center: starfish spermatozoon on the surface of an egg (7,000x magnification) [

108]. Top right: choanoflagellate amoeboid cell [

11]. Bottom right: human macrophage [

109]. Scale bars = 5 μm. Future dissection of the molecular genetic networks governing these cell types in animals and choanoflagellates will test their potential homology. (C) and (D) The temporal-to-spatial transition hypothesis postulates that cell types and cell type regulatory networks found in animals have their evolutionary roots in environmentally-driven cell differentiation in protists [

20,

21]. This hypothesis allows for transcription factor modules to be co-opted during the evolutionary transition, maintain their effect on cell physiology but responding to different inputs. (D) Evidence supporting the TST hypothesis comes from highly similar TF regulons in animals and their closest relatives, in which the regulon is activated in specific environmentally-regulated protist cell types and specific developmentally-regulated animal cell types. Shown here is the T-box family TF Brachyury which is active in the amoeboid cells of

Capsaspora owczarzaki as well as in mesodermal and endodermal lineages in various animal developmental programs. Conserved Brachyury target genes are enriched for functions in amoeboid cell migration [

23].

Figure 1.

The evolutionary foundations of animal transcription factors and cell differentiation. (A) Eukaryotic phylogeny with the origins of transcription factors (TF) and complex multicellularity (red circles) indicated. Rounded rectangles contain names of representative TF families that evolved during eukaryotic evolution and radiation. We define complex multicellularity as that of organisms exhibiting spatiotemporal patterns of cell differentiation [

1]. TF families are evolutionarily coherent groups of genes characterized by unique DNA binding domains shared by all members. Many TF families found in animals were likely already present in the last common eukaryotic ancestor, while other TF families evolved during eukaryotic radiation [

32,

105]. Some TFs evolved along the animal stem lineage (e.g. Ets, NHR, SMAD), while others evolved earlier and are shared by outgroups such as other holozoans, fungi, and amoebozoans (e.g. Runx, p53, and RFX). (B) Cell types of similar form and function can be found in their closest living relatives. Top left: choanoflagellate [

106]. Bottom left: sponge choanocyte (fl = flagellum, n = nucleus) [

107]. Top center: anisogamous gametes from choanoflagellates (photo credit: Alain Garcia de Las Bayonas). Bottom center: starfish spermatozoon on the surface of an egg (7,000x magnification) [

108]. Top right: choanoflagellate amoeboid cell [

11]. Bottom right: human macrophage [

109]. Scale bars = 5 μm. Future dissection of the molecular genetic networks governing these cell types in animals and choanoflagellates will test their potential homology. (C) and (D) The temporal-to-spatial transition hypothesis postulates that cell types and cell type regulatory networks found in animals have their evolutionary roots in environmentally-driven cell differentiation in protists [

20,

21]. This hypothesis allows for transcription factor modules to be co-opted during the evolutionary transition, maintain their effect on cell physiology but responding to different inputs. (D) Evidence supporting the TST hypothesis comes from highly similar TF regulons in animals and their closest relatives, in which the regulon is activated in specific environmentally-regulated protist cell types and specific developmentally-regulated animal cell types. Shown here is the T-box family TF Brachyury which is active in the amoeboid cells of

Capsaspora owczarzaki as well as in mesodermal and endodermal lineages in various animal developmental programs. Conserved Brachyury target genes are enriched for functions in amoeboid cell migration [

23].

Figure 2.

The expansion and diversification of TF repertoires. (A) Bilaterians and cnidarians encode more TFs than early branching animals, which show similar TF numbers to close animal relatives. Shown are TF numbers for individual taxa representing bilaterians, cnidarians, early branching animals, and close animal relatives, with the proportion of pre-animal TF families (gray) and animal-specific TF families (blue). Data is from a comprehensive survey of eukaryotic TF distribution [

27]. Animal-specific families are defined by Sebé-Pedrós

et. al. [

27] (B) Different TF families show different levels of sequence binding specificity and conservation. For each family, an AlphaFold [

110] structure of the human ortholog is shown, as well as the DNA binding specificity empirically determined from human, fly, choanoflagellate, and yeast orthologs. Some TF families like RFX show conservation of DNA binding specificity across more than one billion years of evolution, whereas others like C2H2 zinc fingers have highly divergent DNA binding specificities even between human and fly orthologs. AlphaFold accessions are AF-P51523-F1 (ZNF84), AF-P48378-F1 (RFX2), and AF-Q9NY43-F1 (BARHL2). Motifs downloaded from CIS-BP [

111]:

H. sap ZNF84 (M07736_2.00),

D. mel crol (ortholog to ZNF84; M06116_2.00),

H. sap RFX2 (M03455_2.00),

D. mel RFX (M03963_2.00),

H. sap. BARHL2 (M03158_2.00),

D. mel B-H2 (ortholog to BARHL2; M03811_2.00).

S. ros RFX motif from Coyle

et. al [

42]. Some motif diagrams have been trimmed to remove flanking low-information positions and to facilitate alignment across species. (C) Transcription factors (yellow) physically interact with many other proteins (grey), including histones, the pre-initiation complex (PIC), other TFs (including through dimerization interactions), and with co-activators and co-repressors. These interactions, in turn, affect transcriptional output, partly through post-translational modifications (PTMs) on histones, the PIC, and TFs. (D)

In vitro dimerization assays have revealed the heterodimerization capacity among the bZIP repertoires of various organisms, including bilaterians, cnidarians, and animal relatives [

47]. (E) The cnidarian-bilaterian common ancestor had already increased the combinatorial possibilities of bZIP TFs (compared to a modern choanoflagellate and a modern yeast species) by increasing the proportion of functional heterodimers formed by different bZIP TFs [

47]. Nodes represent bZIP sub-families and lines connect sub-families displaying an

in vitro binding affinity with K

D < 1000 nM.

Figure 2.

The expansion and diversification of TF repertoires. (A) Bilaterians and cnidarians encode more TFs than early branching animals, which show similar TF numbers to close animal relatives. Shown are TF numbers for individual taxa representing bilaterians, cnidarians, early branching animals, and close animal relatives, with the proportion of pre-animal TF families (gray) and animal-specific TF families (blue). Data is from a comprehensive survey of eukaryotic TF distribution [

27]. Animal-specific families are defined by Sebé-Pedrós

et. al. [

27] (B) Different TF families show different levels of sequence binding specificity and conservation. For each family, an AlphaFold [

110] structure of the human ortholog is shown, as well as the DNA binding specificity empirically determined from human, fly, choanoflagellate, and yeast orthologs. Some TF families like RFX show conservation of DNA binding specificity across more than one billion years of evolution, whereas others like C2H2 zinc fingers have highly divergent DNA binding specificities even between human and fly orthologs. AlphaFold accessions are AF-P51523-F1 (ZNF84), AF-P48378-F1 (RFX2), and AF-Q9NY43-F1 (BARHL2). Motifs downloaded from CIS-BP [

111]:

H. sap ZNF84 (M07736_2.00),

D. mel crol (ortholog to ZNF84; M06116_2.00),

H. sap RFX2 (M03455_2.00),

D. mel RFX (M03963_2.00),

H. sap. BARHL2 (M03158_2.00),

D. mel B-H2 (ortholog to BARHL2; M03811_2.00).

S. ros RFX motif from Coyle

et. al [

42]. Some motif diagrams have been trimmed to remove flanking low-information positions and to facilitate alignment across species. (C) Transcription factors (yellow) physically interact with many other proteins (grey), including histones, the pre-initiation complex (PIC), other TFs (including through dimerization interactions), and with co-activators and co-repressors. These interactions, in turn, affect transcriptional output, partly through post-translational modifications (PTMs) on histones, the PIC, and TFs. (D)

In vitro dimerization assays have revealed the heterodimerization capacity among the bZIP repertoires of various organisms, including bilaterians, cnidarians, and animal relatives [

47]. (E) The cnidarian-bilaterian common ancestor had already increased the combinatorial possibilities of bZIP TFs (compared to a modern choanoflagellate and a modern yeast species) by increasing the proportion of functional heterodimers formed by different bZIP TFs [

47]. Nodes represent bZIP sub-families and lines connect sub-families displaying an

in vitro binding affinity with K

D < 1000 nM.

Figure 3.

Assessing the hypothesized evolution of distal enhancer regulation in the animal stem lineage. (A) Enhancers (e.g. EnhA and EnhB) allow genes to be transcriptionally regulated from sites distal to the transcription start site (arrow). Multiple enhancers responsive to different sets of transcription factors can regulate the same gene, allowing genes to be re-utilized in multiple contexts, including in specific tissues (e.g. different regions of the brain) and cell types (e.g. different types of neurons). (B) Enhancers can be directly identified by functional tests or can be identified as candidates by bioinformatic correlates. Functional tests include mutating or removing an enhancer region to test its effect on endogenous gene expression. The ability of putative enhancers can also be tested by measuring the regulation of gene expression in an ectopic context, for instance when the sequence is placed near a reporter gene with a minimal core promoter. Bioinformatic methods used to identify putative enhancers rely on genome-scale chromatin signatures such as chromatin accessibility (through ATAC-seq or DNase hyper-sensitivity) [

23] and histone modifications (H3K27Ac, H3K4me1) [

52,

53,

54], as well as conservation with a known functional enhancer [

112]. “Distal” enhancers are characterized as such regions that can be found a certain distance from the closest transcription start site, a metric that is implemented variably, e.g. 800 bp [

23], 500 bp [

55], 300 bp [

53], and 200 bp [

54]. (C) The phylogenetic distribution of chromatin marks, genes, and genomic features related to the functionality of enhancers does not support the origin of distal enhancers in the animal stem lineage. Some marks of distal enhancers in animals (e.g. H3K4me1, H3K27Ac, p300) predate animal origins while TADs are apparently restricted to vertebrates. Many non-animals also contain rich repertoires of introns. Data is collated from various references: H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac for

Homo sapiens (

H. sap) [

113],

Drosophila melanogaster (

D. mel) [

114],

Nematostella vectensis (

N. vec) [

53],

Amphimedon queenslandica (

A. que) [

54],

Capsaspora owczarzaki (

C. owc) [

23],

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (

S. cer) and

Arabidopsis thaliana (

A. tha) [

70]; p300 for

H. sap [

115],

D. mel [

116],

N. vec [

53],

A. que [

117],

C. owc [

74],

S. cer [

118] and

Arabidopsis thaliana [

119]; CTCF for all taxa [

120] except

C. owc and

S. ros (absence reported here based on BLASTP searches); TADs for

H. sap [

63],

D. mel [

64],

N. vec [

121],

S. cer [

122], and

A. tha [

123]; introns and intergenic distances for all species [

4] except

A. tha [

124]. (D) An enhancer/promoter (E/P) regulatory region in the SV40 viral genome acts as a promoter-proximal element for early infection viral genes, but can also act distally, as demonstrated by its use for driving expression in recombinant plasmids [

49,

71]. (E) STARR-seq assays functionally characterize genomic sequences with enhancer capacity by cloning a library of digested genomic DNA into a construct in which effective enhancers transcribe their own sequence as part of a 3’ UTR and can be identified in high throughput by RNA sequencing. Such assays have shown that thousands of promoter regions are capable of driving distal activation, particularly for housekeeping promoters [

72].

Figure 3.

Assessing the hypothesized evolution of distal enhancer regulation in the animal stem lineage. (A) Enhancers (e.g. EnhA and EnhB) allow genes to be transcriptionally regulated from sites distal to the transcription start site (arrow). Multiple enhancers responsive to different sets of transcription factors can regulate the same gene, allowing genes to be re-utilized in multiple contexts, including in specific tissues (e.g. different regions of the brain) and cell types (e.g. different types of neurons). (B) Enhancers can be directly identified by functional tests or can be identified as candidates by bioinformatic correlates. Functional tests include mutating or removing an enhancer region to test its effect on endogenous gene expression. The ability of putative enhancers can also be tested by measuring the regulation of gene expression in an ectopic context, for instance when the sequence is placed near a reporter gene with a minimal core promoter. Bioinformatic methods used to identify putative enhancers rely on genome-scale chromatin signatures such as chromatin accessibility (through ATAC-seq or DNase hyper-sensitivity) [

23] and histone modifications (H3K27Ac, H3K4me1) [

52,

53,

54], as well as conservation with a known functional enhancer [

112]. “Distal” enhancers are characterized as such regions that can be found a certain distance from the closest transcription start site, a metric that is implemented variably, e.g. 800 bp [

23], 500 bp [

55], 300 bp [

53], and 200 bp [

54]. (C) The phylogenetic distribution of chromatin marks, genes, and genomic features related to the functionality of enhancers does not support the origin of distal enhancers in the animal stem lineage. Some marks of distal enhancers in animals (e.g. H3K4me1, H3K27Ac, p300) predate animal origins while TADs are apparently restricted to vertebrates. Many non-animals also contain rich repertoires of introns. Data is collated from various references: H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac for

Homo sapiens (

H. sap) [

113],

Drosophila melanogaster (

D. mel) [

114],

Nematostella vectensis (

N. vec) [

53],

Amphimedon queenslandica (

A. que) [

54],

Capsaspora owczarzaki (

C. owc) [

23],

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (

S. cer) and

Arabidopsis thaliana (

A. tha) [

70]; p300 for

H. sap [

115],

D. mel [

116],

N. vec [

53],

A. que [

117],

C. owc [

74],

S. cer [

118] and

Arabidopsis thaliana [

119]; CTCF for all taxa [

120] except

C. owc and

S. ros (absence reported here based on BLASTP searches); TADs for

H. sap [

63],

D. mel [

64],

N. vec [

121],

S. cer [

122], and

A. tha [

123]; introns and intergenic distances for all species [

4] except

A. tha [

124]. (D) An enhancer/promoter (E/P) regulatory region in the SV40 viral genome acts as a promoter-proximal element for early infection viral genes, but can also act distally, as demonstrated by its use for driving expression in recombinant plasmids [

49,

71]. (E) STARR-seq assays functionally characterize genomic sequences with enhancer capacity by cloning a library of digested genomic DNA into a construct in which effective enhancers transcribe their own sequence as part of a 3’ UTR and can be identified in high throughput by RNA sequencing. Such assays have shown that thousands of promoter regions are capable of driving distal activation, particularly for housekeeping promoters [

72].

Figure 4.

The pre-animal roots of animal transcriptional networks and cellular differentiation. (A) Bioinformatic [

80] and biochemical [

41] evidence in choanoflagellates and

Capsaspora [

23] supports an ancient role for Myc:Max in regulating ribosome biogenesis genes [

77]. Animals have expanded on this network by increasing the network of heterodimerization interactions through Max/Mdx and Max/Mnt heterodimers that recruit co-repressors, as well as an Mlx branch of this network which works with MLXIP1 and MLXIP2 to regulate metabolism [

76]. (B) The phylogenetic distribution of Myc network genes as well enrichment of E-boxes in ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) genes in animals and outgroups. Data collected from phylogenetic studies of bHLH family genes [

41,

74,

125,

126,

127] and investigations of E-box enrichment in the promoters of ribosome biogenesis genes [

23,

80]. Question marks indicate that bioinformatic analysis for the presence of E-boxes in the promoters of ribosome biogenesis genes have not been performed for this species. (C) Genetic RFX ablation in choanoflagellates and animals results in defective ciliogenesis. Middle: knockout of an RFX TF (cRFXa) in the choanoflagellate

S. rosetta leads to aberrant ciliogenesis, including the collapse of nascent cilia [

42]. RFX2 morpholinos in

Xenopus shorten cilia in many cell types, including epidermal multi-ciliated cells (shown) [

99]. Mutation of the

C. elegans RFX ortholog Daf-19 leads to missing cilia in sensory neurons [

91]. ci = cilium/cilia, d = dendrite, mv = microvillar collar. Scale bars = 5 μm. (D) Schematic of RFX gene duplications and changes in functionality in opisthokonts. Fungal RFX orthologs regulate the cell cycle and DNA damage responses [

96,

97,

98,

128], while choanoflagellates and animals have three RFX orthologs, one of which has a central role in regulating ciliogenesis [

42]. Vertebrates have further duplications within all three of these families, resulting in family members that regulate ciliogenesis in different cell types (e.g. RFX2 in mammalian sperm and RFX3 in multi-ciliated cells) [

93].

Figure 4.

The pre-animal roots of animal transcriptional networks and cellular differentiation. (A) Bioinformatic [

80] and biochemical [

41] evidence in choanoflagellates and

Capsaspora [

23] supports an ancient role for Myc:Max in regulating ribosome biogenesis genes [

77]. Animals have expanded on this network by increasing the network of heterodimerization interactions through Max/Mdx and Max/Mnt heterodimers that recruit co-repressors, as well as an Mlx branch of this network which works with MLXIP1 and MLXIP2 to regulate metabolism [

76]. (B) The phylogenetic distribution of Myc network genes as well enrichment of E-boxes in ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) genes in animals and outgroups. Data collected from phylogenetic studies of bHLH family genes [

41,

74,

125,

126,

127] and investigations of E-box enrichment in the promoters of ribosome biogenesis genes [

23,

80]. Question marks indicate that bioinformatic analysis for the presence of E-boxes in the promoters of ribosome biogenesis genes have not been performed for this species. (C) Genetic RFX ablation in choanoflagellates and animals results in defective ciliogenesis. Middle: knockout of an RFX TF (cRFXa) in the choanoflagellate

S. rosetta leads to aberrant ciliogenesis, including the collapse of nascent cilia [

42]. RFX2 morpholinos in

Xenopus shorten cilia in many cell types, including epidermal multi-ciliated cells (shown) [

99]. Mutation of the

C. elegans RFX ortholog Daf-19 leads to missing cilia in sensory neurons [

91]. ci = cilium/cilia, d = dendrite, mv = microvillar collar. Scale bars = 5 μm. (D) Schematic of RFX gene duplications and changes in functionality in opisthokonts. Fungal RFX orthologs regulate the cell cycle and DNA damage responses [

96,

97,

98,

128], while choanoflagellates and animals have three RFX orthologs, one of which has a central role in regulating ciliogenesis [

42]. Vertebrates have further duplications within all three of these families, resulting in family members that regulate ciliogenesis in different cell types (e.g. RFX2 in mammalian sperm and RFX3 in multi-ciliated cells) [

93].

Acknowledgments

BioRender.com was used to create figure panels 1C,D,E; 2C,D,E; 3A,C,D,E; 4A,D. We thank Alain Garcia de Las Bayonas, Michael Carver, and Jacob Steenwyk for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Brunet, T. & King, N. The Origin of Animal Multicellularity and Cell Differentiation. Dev. Cell 43, 124–140 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. R. & Mortimer, R. K. Use of snail digestive juice in isolation of yeast spore tetrads. J. Bacteriol. 78, 292 (1959). [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. & Tjian, R. Transcription regulation and animal diversity. Nature 424, 147–151 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A., Degnan, B. M. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. The origin of Metazoa: a unicellular perspective. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 498–512 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Erwin, D. H. Evolutionary dynamics of gene regulation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 139, 407–431 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Trillo, I., Roger, A. J., Burger, G., Gray, M. W. & Lang, B. F. A phylogenomic investigation into the origin of metazoa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 664–672 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Shalchian-Tabrizi, K. et al. Multigene phylogeny of choanozoa and the origin of animals. PLoS One 3, e2098 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ros-Rocher, N., Pérez-Posada, A., Leger, M. M. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. The origin of animals: an ancestral reconstruction of the unicellular-to-multicellular transition. Open Biol. 11, 200359 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B. S. C. The Choanoflagellates. (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Levin, T. C. & King, N. Evidence for sex and recombination in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Curr. Biol. 23, 2176–2180 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Brunet, T. et al. A flagellate-to-amoeboid switch in the closest living relatives of animals. Elife 10, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Alegado, R. A. et al. A bacterial sulfonolipid triggers multicellular development in the closest living relatives of animals. Elife 1, e00013 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Woznica, A., Gerdt, J. P., Hulett, R. E., Clardy, J. & King, N. Mating in the Closest Living Relatives of Animals Is Induced by a Bacterial Chondroitinase. Cell 170, 1175-1183.e11 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tikhonenkov, D. V. et al. New Lineage of Microbial Predators Adds Complexity to Reconstructing the Evolutionary Origin of Animals. Curr. Biol. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A. et al. Regulated aggregative multicellularity in a close unicellular relative of metazoa. Elife 2, e01287 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Suga, H. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. Development of ichthyosporeans sheds light on the origin of metazoan multicellularity. Dev. Biol. 377, 284–292 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Dudin, O. et al. Correction: A unicellular relative of animals generates a layer of polarized cells by actomyosin-dependent cellularization. Elife 9, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mah, J. L., Christensen-Dalsgaard, K. K. & Leys, S. P. Choanoflagellate and choanocyte collar-flagellar systems and the assumption of homology. Evol. Dev. 16, 25–37 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Colgren, J. & Nichols, S. A. The significance of sponges for comparative studies of developmental evolution. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 9, e359 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zakhvatkin, A. A. The comparative embryology of the low invertebrates. Sources and method of the origin of metazoan development. Soviet Science (1949).

- Mikhailov, K. V. et al. The origin of Metazoa: a transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation. Bioessays 31, 758–768 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Dayel, M. J. et al. Cell differentiation and morphogenesis in the colony-forming choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Dev. Biol. 357, 73–82 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A. et al. The Dynamic Regulatory Genome of Capsaspora and the Origin of Animal Multicellularity. Cell 165, 1224–1237 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Lolas, M., Valenzuela, P. D. T., Tjian, R. & Liu, Z. Charting Brachyury-mediated developmental pathways during early mouse embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 4478–4483 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. M. & McClay, D. R. The role of Brachyury (T) during gastrulation movements in the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. Dev. Biol. 239, 132–147 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S. A. et al. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 175, 598–599 (2018). [CrossRef]

- de Mendoza, A. et al. Transcription factor evolution in eukaryotes and the assembly of the regulatory toolkit in multicellular lineages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, E4858-66 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, J. F., Zimmer, F. & Bornberg-Bauer, E. Mechanisms of transcription factor evolution in Metazoa. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6287–6297 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Shimeld, S. M., Degnan, B. & Luke, G. N. Evolutionary genomics of the Fox genes: origin of gene families and the ancestry of gene clusters. Genomics 95, 256–260 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Joho, K. E., Darby, M. K., Crawford, E. T. & Brown, D. D. A finger protein structurally similar to TFIIIA that binds exclusively to 5S RNA in Xenopus. Cell 61, 293–300 (1990). [CrossRef]

- Mesika, A., Ben-Dor, S., Laviad, E. L. & Futerman, A. H. A new functional motif in Hox domain-containing ceramide synthases: identification of a novel region flanking the Hox and TLC domains essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27366–27373 (2007). [CrossRef]

- de Mendoza, A. & Sebé-Pedrós, A. Origin and evolution of eukaryotic transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 58–59, 25–32 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Finn, R. D. et al. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D190–D199 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M. et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature 466, 720–726 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. F. et al. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications for cell type evolution. Science 342, 1242592 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M. et al. The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans. Nature 454, 955–960 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M. A., Lau, A. O. T. & Johnson, P. J. Structural basis of core promoter recognition in a primitive eukaryote. Cell 115, 413–424 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S., Babu, M. M., Iyer, L. M. & Aravind, L. Discovery of the principal specific transcription factors of Apicomplexa and their implication for the evolution of the AP2-integrase DNA binding domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 3994–4006 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. R., Tuch, B. B. & Johnson, A. D. Extensive DNA-binding specificity divergence of a conserved transcription regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 7493–7498 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S. A. et al. Similarity regression predicts evolution of transcription factor sequence specificity. Nat. Genet. 51, 981–989 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Young, S. L. et al. Premetazoan ancestry of the Myc-Max network. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2961–2971 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Coyle, M. C. et al. An RFX transcription factor regulates ciliogenesis in the closest living relatives of animals. Curr. Biol. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A. et al. Early evolution of the T-box transcription factor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 16050–16055 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Albertin, C. B. et al. The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties. Nature 524, 220–224 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Plevin, M. J., Mills, M. M. & Ikura, M. The LxxLL motif: a multifunctional binding sequence in transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 66–69 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Reinke, A. W., Bhimsaria, D., Keating, A. E. & Ansari, A. Z. Combinatorial bZIP dimers display complex DNA-binding specificity landscapes. Elife 6, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Reinke, A. W., Baek, J., Ashenberg, O. & Keating, A. E. Networks of bZIP protein-protein interactions diversified over a billion years of evolution. Science 340, 730–734 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. Transcriptional enhancers in animal development and evolution. Curr. Biol. 20, R754-63 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Banerji, J., Rusconi, S. & Schaffner, W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell 27, 299–308 (1981). [CrossRef]

- Levine, M., Cattoglio, C. & Tjian, R. Looping back to leap forward: transcription enters a new era. Cell 157, 13–25 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y. F. et al. Adaptive evolution of pelvic reduction in sticklebacks by recurrent deletion of a Pitx1 enhancer. Science 327, 302–305 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Visel, A. et al. ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature 457, 854–858 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, M. et al. Evolutionary conservation of the eumetazoan gene regulatory landscape. Genome Res. 24, 639–650 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Gaiti, F. et al. Landscape of histone modifications in a sponge reveals the origin of animal cis-regulatory complexity. Elife 6, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Páramo, P., Roper, K., Degnan, S. M., Degnan, B. M. & Wong, E. S. Distal regulation, silencers, and a shared combinatorial syntax are hallmarks of animal embryogenesis. Genome Res. 32, 474–487 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wong, E. S. et al. Deep conservation of the enhancer regulatory code in animals. Science 370, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dobi, K. C. & Winston, F. Analysis of transcriptional activation at a distance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 5575–5586 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Rickels, R. et al. Histone H3K4 monomethylation catalyzed by Trr and mammalian COMPASS-like proteins at enhancers is dispensable for development and viability. Nat. Genet. 49, 1647–1653 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Dorighi, K. M. et al. Mll3 and Mll4 Facilitate Enhancer RNA Synthesis and Transcription from Promoters Independently of H3K4 Monomethylation. Mol. Cell 66, 568-576.e4 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A. et al. Early metazoan cell type diversity and the evolution of multicellular gene regulation. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 1176–1188 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Simakov, O. et al. Deeply conserved synteny and the evolution of metazoan chromosomes. Sci Adv 8, eabi5884 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Irimia, M. et al. Extensive conservation of ancient microsynteny across metazoans due to cis-regulatory constraints. Genome Res. 22, 2356–2367 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Beagan, J. A. & Phillips-Cremins, J. E. On the existence and functionality of topologically associating domains. Nat. Genet. 52, 8–16 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hehmeyer, J., Spitz, F. & Marlow, H. Shifting landscapes: the role of 3D genomic organizations in gene regulatory strategies. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 81, 102064 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Calderon, L. et al. Cohesin-dependence of neuronal gene expression relates to chromatin loop length. Elife 11, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rinzema, N. J. et al. Building regulatory landscapes reveals that an enhancer can recruit cohesin to create contact domains, engage CTCF sites and activate distant genes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 29, 563–574 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Matthews, N. E. & White, R. Chromatin Architecture in the Fly: Living without CTCF/Cohesin Loop Extrusion?: Alternating Chromatin States Provide a Basis for Domain Architecture in Drosophila. Bioessays 41, e1900048 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, A. et al. CTCF loss has limited effects on global genome architecture in Drosophila despite critical regulatory functions. Nat. Commun. 12, 1011 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M. J. et al. Evolutionarily Conserved Principles Predict 3D Chromatin Organization. Mol. Cell 67, 837-852.e7 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Grau-Bové, X. et al. A phylogenetic and proteomic reconstruction of eukaryotic chromatin evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1007–1023 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Herr, W. The SV40 enhancer: Transcriptional regulation through a hierarchy of combinatorial interactions. Semin. Virol. 4, 3–13 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, M. A. et al. Enhancer-core-promoter specificity separates developmental and housekeeping gene regulation. Nature 518, 556–559 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Grau-Bové, X. et al. Dynamics of genomic innovation in the unicellular ancestry of animals. Elife 6, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A., de Mendoza, A., Lang, B. F., Degnan, B. M. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. Unexpected repertoire of metazoan transcription factors in the unicellular holozoan Capsaspora owczarzaki. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1241–1254 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Eilers, M. & Eisenman, R. N. Myc’s broad reach. Genes Dev. 22, 2755–2766 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P. A., Freie, B. W., Mathsyaraja, H. & Eisenman, R. N. The MYC transcription factor network: balancing metabolism, proliferation and oncogenesis. Front. Med. 12, 412–425 (2018). [CrossRef]

- van Riggelen, J., Yetil, A. & Felsher, D. W. MYC as a regulator of ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 301–309 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Grandori, C. et al. c-Myc binds to human ribosomal DNA and stimulates transcription of rRNA genes by RNA polymerase I. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 311–318 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S. S., Li, L., Orian, A., Eisenman, R. N. & Edgar, B. A. Myc-dependent regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis during Drosophila development. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 295–302 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. J., Cole, M. D. & Erives, A. J. Evolution of the holozoan ribosome biogenesis regulon. BMC Genomics 9, 442 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-K. et al. Cell-type specific and combinatorial usage of diverse transcription factors revealed by genome-wide binding studies in multiple human cells. Genome Res. 22, 9–24 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Walz, S. et al. Activation and repression by oncogenic MYC shape tumour-specific gene expression profiles. Nature 511, 483–487 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lorenzin, F. et al. Different promoter affinities account for specificity in MYC-dependent gene regulation. Elife 5, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sabò, A. & Amati, B. Genome recognition by MYC. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Sabò, A. et al. Selective transcriptional regulation by Myc in cellular growth control and lymphomagenesis. Nature 511, 488–492 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Grandori, C., Cowley, S. M., James, L. P. & Eisenman, R. N. The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 653–699 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Cowling, V. H., Chandriani, S., Whitfield, M. L. & Cole, M. D. A conserved Myc protein domain, MBIV, regulates DNA binding, apoptosis, transformation, and G2 arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 4226–4239 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Das, S. K., Lewis, B. A. & Levens, D. MYC: a complex problem. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 235–246 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Quigley, I. K. & Kintner, C. Rfx2 Stabilizes Foxj1 Binding at Chromatin Loops to Enable Multiciliated Cell Gene Expression. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006538 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Dubruille, R. et al. Drosophila regulatory factor X is necessary for ciliated sensory neuron differentiation. Development 129, 5487–5498 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, P., Adler, H. T. & Thomas, J. H. The RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19 regulates sensory neuron cilium formation in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 5, 411–421 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Reiter, J. F. & Leroux, M. R. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 533–547 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Choksi, S. P., Lauter, G., Swoboda, P. & Roy, S. Switching on cilia: transcriptional networks regulating ciliogenesis. Development 141, 1427–1441 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Jolma, A. et al. DNA-binding specificities of human transcription factors. Cell 152, 327–339 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Adl, S. M. et al. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 59, 429–493 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Hao, B. et al. Candida albicans RFX2 encodes a DNA binding protein involved in DNA damage responses, morphogenesis, and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 8, 627–639 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Y. & McLeod, M. The sak1 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe encodes an RFX family DNA-binding protein that positively regulates cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated exit from the mitotic cell cycle. Molecular and Cellular Biology vol. 15 1479–1488 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.15.3.1479 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Zhou, Z. & Elledge, S. J. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell 94, 595–605 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-I. et al. RFX2 is broadly required for ciliogenesis during vertebrate development. Dev. Biol. 363, 155–165 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Kistler, W. S. et al. RFX2 Is a Major Transcriptional Regulator of Spermiogenesis. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005368 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bonnafe, E. et al. The transcription factor RFX3 directs nodal cilium development and left-right asymmetry specification. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4417–4427 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Feng, C., Xu, W. & Zuo, Z. Knockout of the regulatory factor X1 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 715–717 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Bugeja, H. E., Hynes, M. J. & Andrianopoulos, A. The RFX protein RfxA is an essential regulator of growth and morphogenesis in Penicillium marneffei. Eukaryot. Cell 9, 578–591 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S. R. et al. Premetazoan genome evolution and the regulation of cell differentiation in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Genome Biol. 14, R15 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Weirauch, M. T. & Hughes, T. R. A catalogue of eukaryotic transcription factor types, their evolutionary origin, and species distribution. Subcell. Biochem. 52, 25–73 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S. A., Dayel, M. J. & King, N. Genomic, phylogenetic, and cell biological insights into metazoan origins. (2009).

- Leys, S. P. & Eerkes-Medrano, D. I. Feeding in a calcareous sponge: particle uptake by pseudopodia. Biol. Bull. 211, 157–171 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. M., Shalgi, R. & Dekel, N. Mammalian fertilization as seen with the scanning electron microscope. Am. J. Anat. 174, 357–372 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Guehrs, E. et al. Quantification of silver nanoparticle uptake and distribution within individual human macrophages by FIB/SEM slice and view. J. Nanobiotechnology 15, 21 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Weirauch, M. T. et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell 158, 1431–1443 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Villar, D. et al. Enhancer evolution across 20 mammalian species. Cell 160, 554–566 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B. A. et al. Organismal differences in post-translational modifications in histones H3 and H4. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7641–7655 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, P. V. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471, 480–485 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Rada-Iglesias, A. et al. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature 470, 279–283 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Akimaru, H. et al. Drosophila CBP is a co-activator of cubitus interruptus in hedgehog signalling. Nature 386, 735–738 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Sogabe, S. et al. Pluripotency and the origin of animal multicellularity. Nature 570, 519–522 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Eckner, R. p300 and CBP as transcriptional regulators and targets of oncogenic events. Biol. Chem. 377, 685–688 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Bordoli, L., Netsch, M., Lüthi, U., Lutz, W. & Eckner, R. Plant orthologs of p300/CBP: conservation of a core domain in metazoan p300/CBP acetyltransferase-related proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 589–597 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Heger, P., Marin, B., Bartkuhn, M., Schierenberg, E. & Wiehe, T. The chromatin insulator CTCF and the emergence of metazoan diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 17507–17512 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, B. et al. Topological structures and syntenic conservation in sea anemone genomes. Nat. Commun. 14, 8270 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-H. S. et al. Mapping Nucleosome Resolution Chromosome Folding in Yeast by Micro-C. Cell 162, 108–119 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Feng, S. et al. Genome-wide Hi-C analyses in wild-type and mutants reveal high-resolution chromatin interactions in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 55, 694–707 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lamesch, P. et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1202-10 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Simionato, E. et al. Origin and diversification of the basic helix-loop-helix gene family in metazoans: insights from comparative genomics. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 33 (2007). [CrossRef]

- McFerrin, L. G. & Atchley, W. R. Evolution of the Max and Mlx networks in animals. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 915–937 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Erives, A. & Fritzsch, B. A Screen for Gene Paralogies Delineating Evolutionary Branching Order of Early Metazoa. G3 10, 811–826 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Min, K. et al. Transcription factor RFX1 is crucial for maintenance of genome integrity in Fusarium graminearum. Eukaryot. Cell 13, 427–436 (2014). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).